Gasdermin D Cleavage and Cytokine Release, Indicative of Pyroptotic Cell Death, Induced by Ophiobolin A in Breast Cancer Cell Lines

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

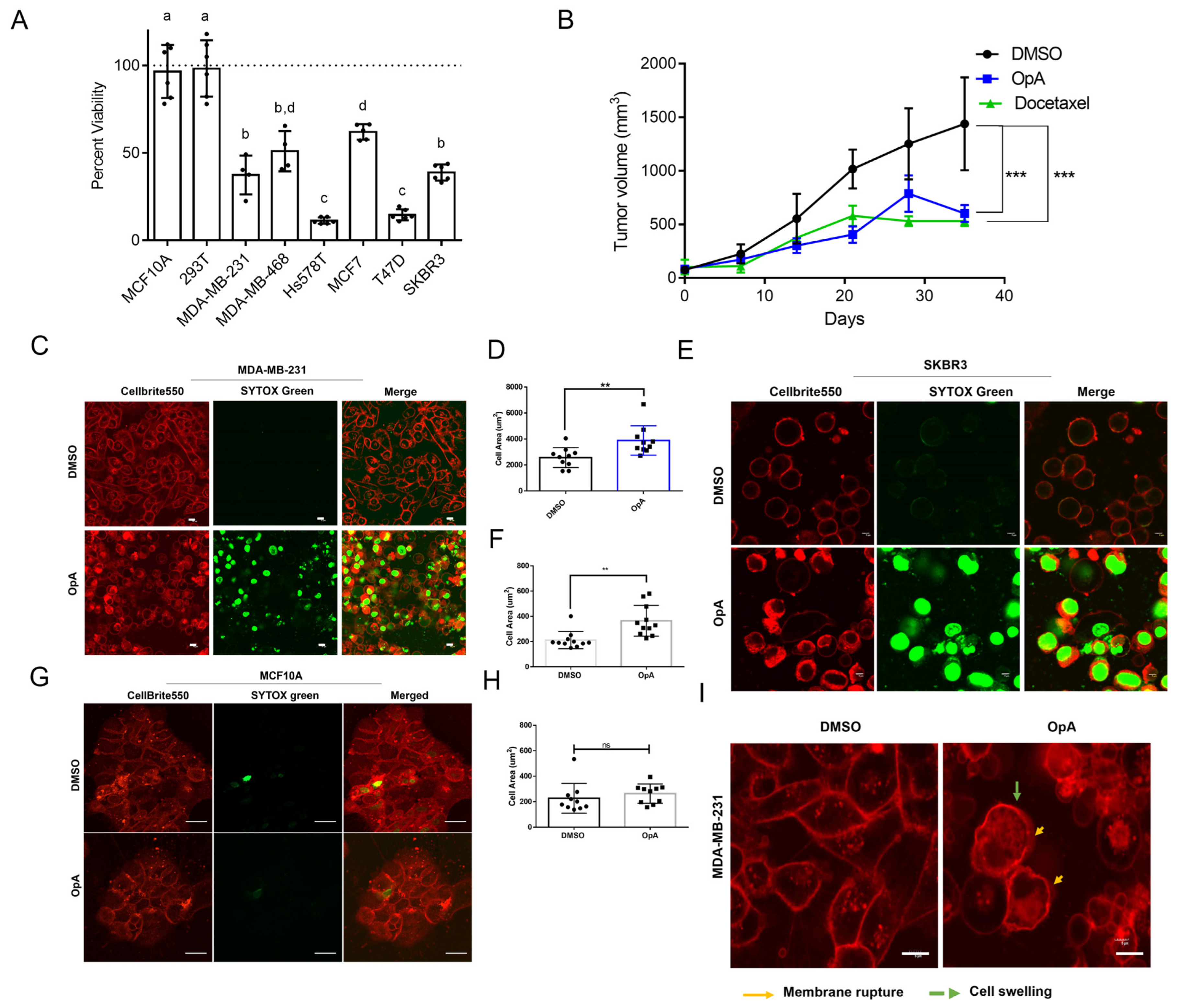

2.1. OpA-Induced Cytotoxicity Is Selective to Cancer Cells and Is Potent In Vivo

2.2. Ophiobolin A Triggers Morphological Changes Consistent with Lytic Cell Death

2.3. Ophiobolin A Requires RIPK1 Activity and Can Induce Necrosome Formation upon RIPK3 Overexpression

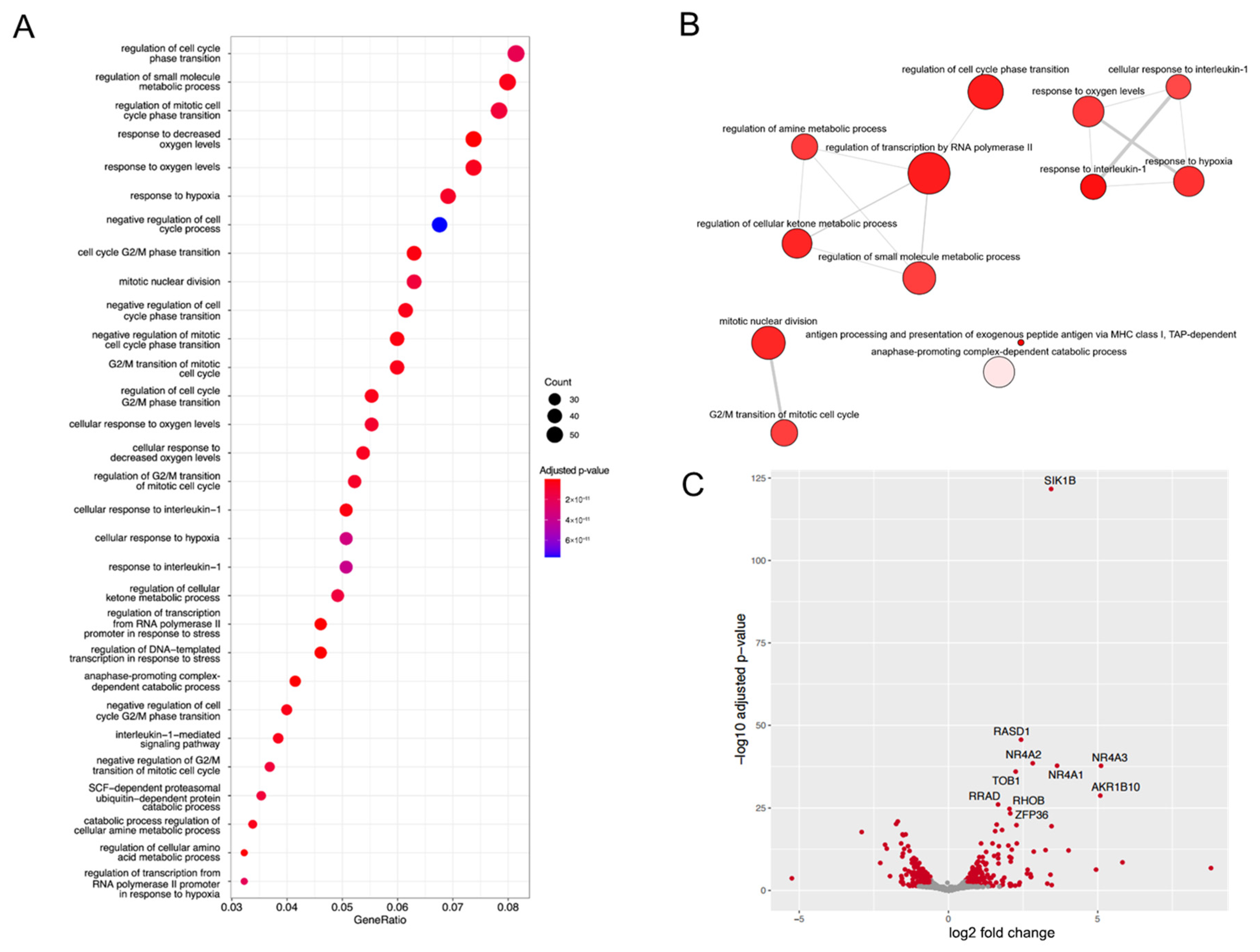

2.4. Ophiobolin A Enhances the Expression of Cytokines and Triggers Inflammatory Genes

2.5. Ophiobolin A Facilitates Release of Cytokines and Cleavage of Gasdermin D Favoring Pyroptotic Cell Death

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture and Stable Cell Line

4.2. Ophiobolin A Source and Purification

4.3. Cell Culture Treatments and Viability Assay

4.4. Autophagy Assay

4.5. Annexin V Assay

4.6. Intracellular Calcium Accumulation Assay

4.7. Live Cell Imaging

4.8. Immunoblotting

4.9. Reverse Transcription and Real-Time Quantitative PCR

4.10. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

4.11. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes

4.12. Gene Ontology and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

4.13. Tumor Growth

4.14. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.; Greer, Y.; Lipkowitz, S.; Takebe, N. Novel Apoptosis-Inducing Agents for the Treatment of Cancer, a New Arsenal in the Toolbox. Cancers 2019, 11, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J.C. Apoptosis-based therapies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2002, 1, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Reilly, E.A.; Gubbins, L.; Sharma, S.; Tully, R.; Guang, M.H.; Weiner-Gorzel, K.; McCaffrey, J.; Harrison, M.; Furlong, F.; Kell, M.; et al. The fate of chemoresistance in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC). BBA Clin. 2015, 3, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, L.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, S.; Wang, F.T.; Zhou, T.T.; Liu, B.; Bao, J.K. Programmed cell death pathways in cancer: A review of apoptosis, autophagy and programmed necrosis. Cell Prolif. 2012, 45, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, L.; Vitale, I.; Aaronson, S.A.; Abrams, J.M.; Adam, D.; Agostinis, P.; Alnemri, E.S.; Altucci, L.; Amelio, I.; Andrews, D.W.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 486–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, I.; Pietrocola, F.; Guilbaud, E.; Aaronson, S.A.; Abrams, J.M.; Adam, D.; Agostini, M.; Agostinis, P.; Alnemri, E.S.; Altucci, L.; et al. Apoptotic cell death in disease-Current understanding of the NCCD 2023. Cell Death Differ. 2023, 30, 1097–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Zou, C.; Yuan, J. Genetic Regulation of RIPK1 and Necroptosis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2021, 55, 235–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Niu, F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Su, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Qian, L.; Liu, P.; et al. Ferroptosis: A cell death connecting oxidative stress, inflammation and cardiovascular diseases. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, S.; Dharan, A.; V, J.P.; Pal, S.; Nair, B.G.; Kar, R.; Mishra, N. Paraptosis: A unique cell death mode for targeting cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1159409, Correction in Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1274076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ye, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhou, J.; Xiang, A.; Lin, X.; Guo, J.; Hu, S.; Rui, T.; Liu, J. Targeting pyroptosis in breast cancer: Biological functions and therapeutic potentials on It. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Qi, L.; Li, L.; Li, Y. The casp-3/GSDME signal pathway as a switch between apoptosis and pyroptosis. Cell Death Discov. 2020, 6, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weindel, C.G.; Martinez, E.L.; Zhao, X.; Mabry, C.J.; Bell, S.L.; Vail, K.J.; Coleman, A.K.; VanPortfliet, J.J.; Zhao, B.; Wagner, A.R.; et al. Mitochondrial ROS promotes susceptibility to infection via gasdermin D-mediated necroptosis. Cell 2022, 185, 3214–3231.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Xiong, A.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Li, G.; He, X. PANoptosis: Bridging apoptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis in cancer progression and treatment. Cancer Gene Ther. 2024, 31, 970–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bladt, T.T.; Durr, C.; Knudsen, P.B.; Kildgaard, S.; Frisvad, J.C.; Gotfredsen, C.H.; Seiffert, M.; Larsen, T.O. Bio-activity and dereplication-based discovery of ophiobolins and other fungal secondary metabolites targeting leukemia cells. Molecules 2013, 18, 14629–14650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Reisenauer, K.N.; Masi, M.; Evidente, A.; Taube, J.H.; Romo, D. Pharmacophore-Directed Retrosynthesis Applied to Ophiobolin A: Simplified Bicyclic Derivatives Displaying Anticancer Activity. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 8307–8312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masi, M.; Dasari, R.; Evidente, A.; Mathieu, V.; Kornienko, A. Chemistry and biology of ophiobolin A and its congeners. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 29, 859–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisenauer, K.N.; Aroujo, J.; Tao, Y.F.; Ranganathan, S.; Romo, D.; Taube, J.H. Therapeutic vulnerabilities of cancer stem cells and effects of natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2023, 40, 1432–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bury, M.; Girault, A.; Megalizzi, V.; Spiegl-Kreinecker, S.; Mathieu, V.; Berger, W.; Evidente, A.; Kornienko, A.; Gailly, P.; Vandier, C.; et al. Ophiobolin A induces paraptosis-like cell death in human glioblastoma cells by decreasing BKCa channel activity. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4, e561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, R.; Lodge, T.; Evidente, A.; Kiss, R.; Townley, H. Ophiobolin A, a sesterpenoid fungal phytotoxin, displays different mechanisms of cell death in mammalian cells depending upon the cancer cell origin. Int. J. Oncol. 2017, 50, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodolfo, C.; Rocco, M.; Cattaneo, L.; Tartaglia, M.; Sassi, M.; Aducci, P.; Scaloni, A.; Camoni, L.; Marra, M. Ophiobolin A Induces Autophagy and Activates the Mitochondrial Pathway of Apoptosis in Human Melanoma Cells. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisenauer, K.N.; Tao, Y.; Das, P.; Song, S.; Svatek, H.; Patel, S.D.; Mikhail, S.; Ingros, A.; Sheesley, P.; Masi, M.; et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition sensitizes breast cancer cells to cell death via the fungus-derived sesterterpenoid ophiobolin A. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Lee, D.M.; Woo, H.G.; Kim, K.D.; Lee, H.J.; Kwon, Y.J.; Choi, K.S. RNAi Screening-based Identification of USP10 as a Novel Regulator of Paraptosis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Gueydan, C.; Han, J. Plasma membrane changes during programmed cell deaths. Cell Res. 2018, 28, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenabeele, P.; Grootjans, S.; Callewaert, N.; Takahashi, N. Necrostatin-1 blocks both RIPK1 and IDO: Consequences for the study of cell death in experimental disease models. Cell Death Differ. 2013, 20, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, N.; Duprez, L.; Grootjans, S.; Cauwels, A.; Nerinckx, W.; DuHadaway, J.B.; Goossens, V.; Roelandt, R.; Van Hauwermeiren, F.; Libert, C.; et al. Necrostatin-1 analogues: Critical issues on the specificity, activity and in vivo use in experimental disease models. Cell Death Dis. 2012, 3, e437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; He, S.; Chen, S.; Liao, D.; Wang, L.; Yan, J.; Liu, W.; Lei, X.; et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell 2012, 148, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, G.B.; Morgan, M.J.; Lee, D.G.; Kim, W.J.; Yoon, J.H.; Koo, J.S.; Kim, S.I.; Kim, S.J.; Son, M.K.; Hong, S.S.; et al. Methylation-dependent loss of RIP3 expression in cancer represses programmed necrosis in response to chemotherapeutics. Cell Res. 2015, 25, 707–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, W.; Shi, X.; Ding, J.; Liu, W.; He, H.; Wang, K.; Shao, F. Chemotherapy drugs induce pyroptosis through caspase-3 cleavage of a gasdermin. Nature 2017, 547, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, M.; Ueno, A.; Saga, K.; Fukuzawa, M.; Kaneda, Y. Accumulation of cytosolic calcium induces necroptotic cell death in human neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 1056–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crean, D.; Murphy, E.P. Targeting NR4A Nuclear Receptors to Control Stromal Cell Inflammation, Metabolism, Angiogenesis, and Tumorigenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 589770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.J.; Liu, X.; Xia, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Ruan, J.; Luo, X.; Lou, X.; Bai, Y.; et al. FDA-approved disulfiram inhibits pyroptosis by blocking gasdermin D pore formation. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Han, X. Disulfiram inhibits inflammation and fibrosis in a rat unilateral ureteral obstruction model by inhibiting gasdermin D cleavage and pyroptosis. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 70, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Bracey, S.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, T.S. Regulation of gasdermins in pyroptosis and cytokine release. Adv. Immunol. 2023, 158, 75–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Rong, R.; Xia, X. Spotlight on pyroptosis: Role in pathogenesis and therapeutic potential of ocular diseases. J. Neuroinflamm. 2022, 19, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; He, W.T.; Hu, L.; Li, J.; Fang, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, Z.; Huang, K.; Han, J. Pyroptosis is driven by non-selective gasdermin-D pore and its morphology is different from MLKL channel-mediated necroptosis. Cell Res. 2016, 26, 1007–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Xiao, X.; Wang, G.; Uosef, A.; Lou, X.; Arnold, P.; Wang, Y.; Kong, G.; Wen, M.; Minze, L.J.; et al. Gasdermin D-mediated pyroptosis is regulated by AMPK-mediated phosphorylation in tumor cells. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devant, P.; Borsic, E.; Ngwa, E.M.; Xiao, H.; Chouchani, E.T.; Thiagarajah, J.R.; Hafner-Bratkovic, I.; Evavold, C.L.; Kagan, J.C. Gasdermin D pore-forming activity is redox-sensitive. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dho, S.H.; Cho, M.; Woo, W.; Jeong, S.; Kim, L.K. Caspases as master regulators of programmed cell death: Apoptosis, pyroptosis and beyond. Exp. Mol. Med. 2025, 57, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesavardhana, S.; Malireddi, R.K.S.; Kanneganti, T.D. Caspases in Cell Death, Inflammation, and Pyroptosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 38, 567–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demarco, B.; Grayczyk, J.P.; Bjanes, E.; Le Roy, D.; Tonnus, W.; Assenmacher, C.A.; Radaelli, E.; Fettrelet, T.; Mack, V.; Linkermann, A.; et al. Caspase-8-dependent gasdermin D cleavage promotes antimicrobial defense but confers susceptibility to TNF-induced lethality. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igney, F.H.; Krammer, P.H. Death and anti-death: Tumour resistance to apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, S.M.; Corriden, R.; Nizet, V. How Neutrophils Meet Their End. Trends Immunol. 2020, 41, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X.; Lei, L.; Wang, S.; Hu, J.; Zhang, G. Necroptosis and its role in infectious diseases. Apoptosis 2020, 25, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annibaldi, A.; Meier, P. Checkpoints in TNF-Induced Cell Death: Implications in Inflammation and Cancer. Trends Mol. Med. 2018, 24, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; McQuade, T.; Siemer, A.B.; Napetschnig, J.; Moriwaki, K.; Hsiao, Y.S.; Damko, E.; Moquin, D.; Walz, T.; McDermott, A.; et al. The RIP1/RIP3 necrosome forms a functional amyloid signaling complex required for programmed necrosis. Cell 2012, 150, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Wang, K.; Liu, W.; She, Y.; Sun, Q.; Shi, J.; Sun, H.; Wang, D.C.; Shao, F. Pore-forming activity and structural autoinhibition of the gasdermin family. Nature 2016, 535, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Feng, M.; Zhang, S. Molecular Characteristics of Cell Pyroptosis and Its Inhibitors: A Review of Activation, Regulation, and Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 16115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, F.H.M.; Yeap, H.W.; Liu, Z.; Rosli, S.N.; Low, K.E.; Bonne, I.; Wu, Y.; Chong, S.Z.; Chen, K.W. Plasticity of cell death pathways ensures GSDMD activation during Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malireddi, R.K.S.; Kesavardhana, S.; Karki, R.; Kancharana, B.; Burton, A.R.; Kanneganti, T.D. RIPK1 Distinctly Regulates Yersinia-Induced Inflammatory Cell Death, PANoptosis. Immunohorizons 2020, 4, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Yang, Y.; Meng, X.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, H. PANoptosis: Mechanisms, biology, and role in disease. Immunol. Rev. 2024, 321, 246–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christgen, S.; Zheng, M.; Kesavardhana, S.; Karki, R.; Malireddi, R.K.S.; Banoth, B.; Place, D.E.; Briard, B.; Sharma, B.R.; Tuladhar, S.; et al. Identification of the PANoptosome: A Molecular Platform Triggering Pyroptosis, Apoptosis, and Necroptosis (PANoptosis). Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Karki, R.; Wang, Y.; Nguyen, L.N.; Kalathur, R.C.; Kanneganti, T.D. AIM2 forms a complex with pyrin and ZBP1 to drive PANoptosis and host defence. Nature 2021, 597, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evidente, A.; Andolfi, A.; Cimmino, A.; Vurro, M.; Fracchiolla, M.; Charudattan, R. Herbicidal potential of ophiobolins produced by Drechslera gigantea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 1779–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heid, C.A.; Stevens, J.; Livak, K.J.; Williams, P.M. Real time quantitative PCR. Genome Res. 1996, 6, 986–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patro, R.; Duggal, G.; Love, M.I.; Irizarry, R.A.; Kingsford, C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Soneson, C.; Hickey, P.F.; Johnson, L.K.; Pierce, N.T.; Shepherd, L.; Morgan, M.; Patro, R. Tximeta: Reference sequence checksums for provenance identification in RNA-seq. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1007664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.M.S.; Wanderley, C.W.S.; Veras, F.P.; Sonego, F.; Nascimento, D.C.; Goncalves, A.V.; Martins, T.V.; Colon, D.F.; Borges, V.F.; Brauer, V.S.; et al. Gasdermin D inhibition prevents multiple organ dysfunction during sepsis by blocking NET formation. Blood 2021, 138, 2702–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Reilly, B.; Jha, A.; Murao, A.; Lee, Y.; Brenner, M.; Aziz, M.; Wang, P. Active Release of eCIRP via Gasdermin D Channels to Induce Inflammation in Sepsis. J. Immunol. 2022, 208, 2184–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ranganathan, S.; Ojo, T.; Subramanian, A.; Tobin, J.; Kornienko, A.; Boari, A.; Evidente, A.; Benton, M.L.; Romo, D.; Taube, J.H. Gasdermin D Cleavage and Cytokine Release, Indicative of Pyroptotic Cell Death, Induced by Ophiobolin A in Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020618

Ranganathan S, Ojo T, Subramanian A, Tobin J, Kornienko A, Boari A, Evidente A, Benton ML, Romo D, Taube JH. Gasdermin D Cleavage and Cytokine Release, Indicative of Pyroptotic Cell Death, Induced by Ophiobolin A in Breast Cancer Cell Lines. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020618

Chicago/Turabian StyleRanganathan, Santhalakshmi, Tolulope Ojo, Alagu Subramanian, Jenna Tobin, Alexander Kornienko, Angela Boari, Antonio Evidente, Mary Lauren Benton, Daniel Romo, and Joseph H. Taube. 2026. "Gasdermin D Cleavage and Cytokine Release, Indicative of Pyroptotic Cell Death, Induced by Ophiobolin A in Breast Cancer Cell Lines" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020618

APA StyleRanganathan, S., Ojo, T., Subramanian, A., Tobin, J., Kornienko, A., Boari, A., Evidente, A., Benton, M. L., Romo, D., & Taube, J. H. (2026). Gasdermin D Cleavage and Cytokine Release, Indicative of Pyroptotic Cell Death, Induced by Ophiobolin A in Breast Cancer Cell Lines. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 618. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020618