Vitamin E Modulates Hepatic Extracellular Adenosine Signaling to Attenuate Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

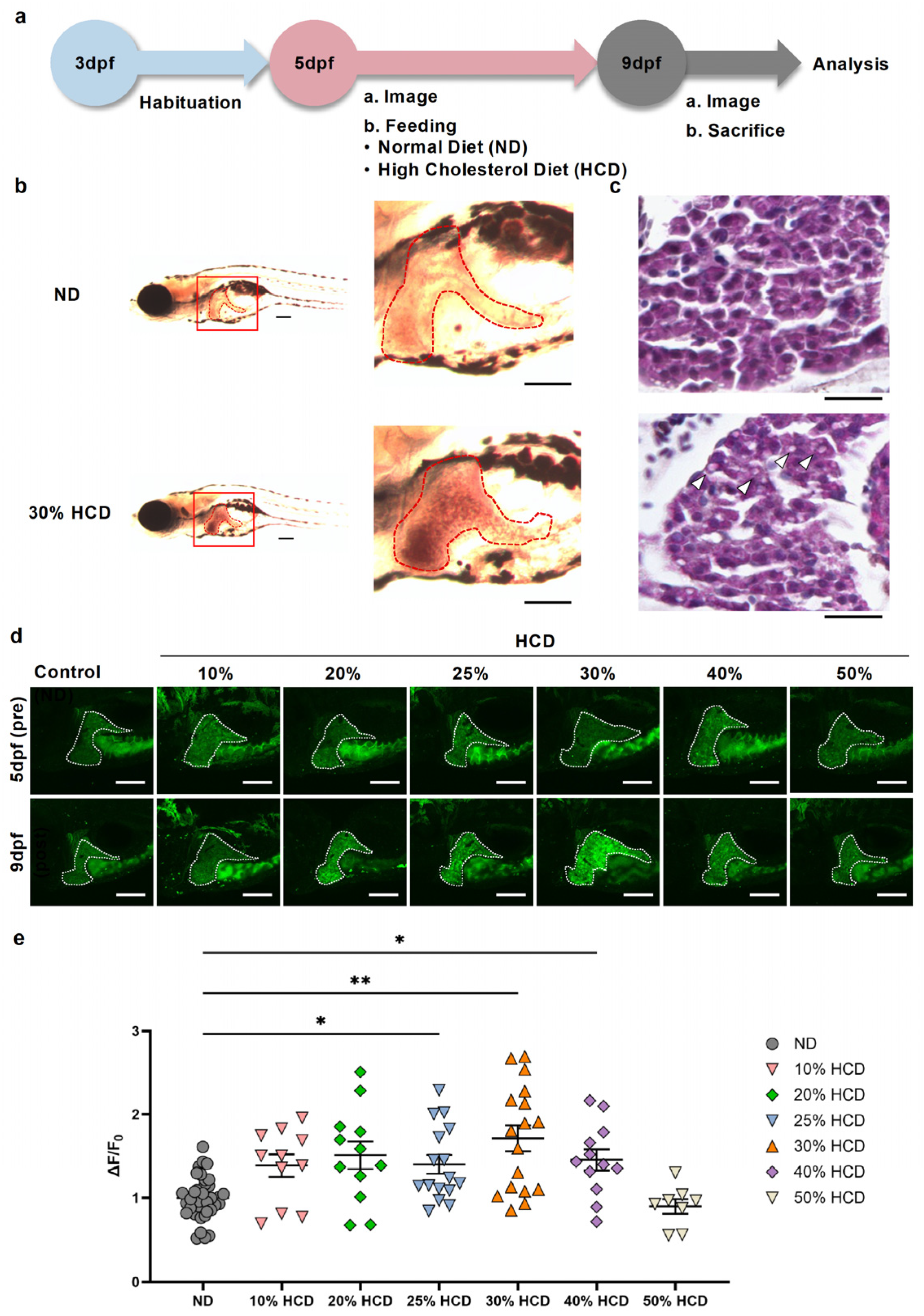

2.1. Establishment of an HCD-Induced MASLD Model Using Zebrafish and Evaluation of Hepatic Extracellular Adenosine Dynamics

2.2. HCD Induces Inflammatory, Inflammasome-Related, and ER-Stress Gene Expression in the Zebrafish Liver

2.3. Vitamin E Alleviates Hepatic Steatosis by Reducing eAdo Levels

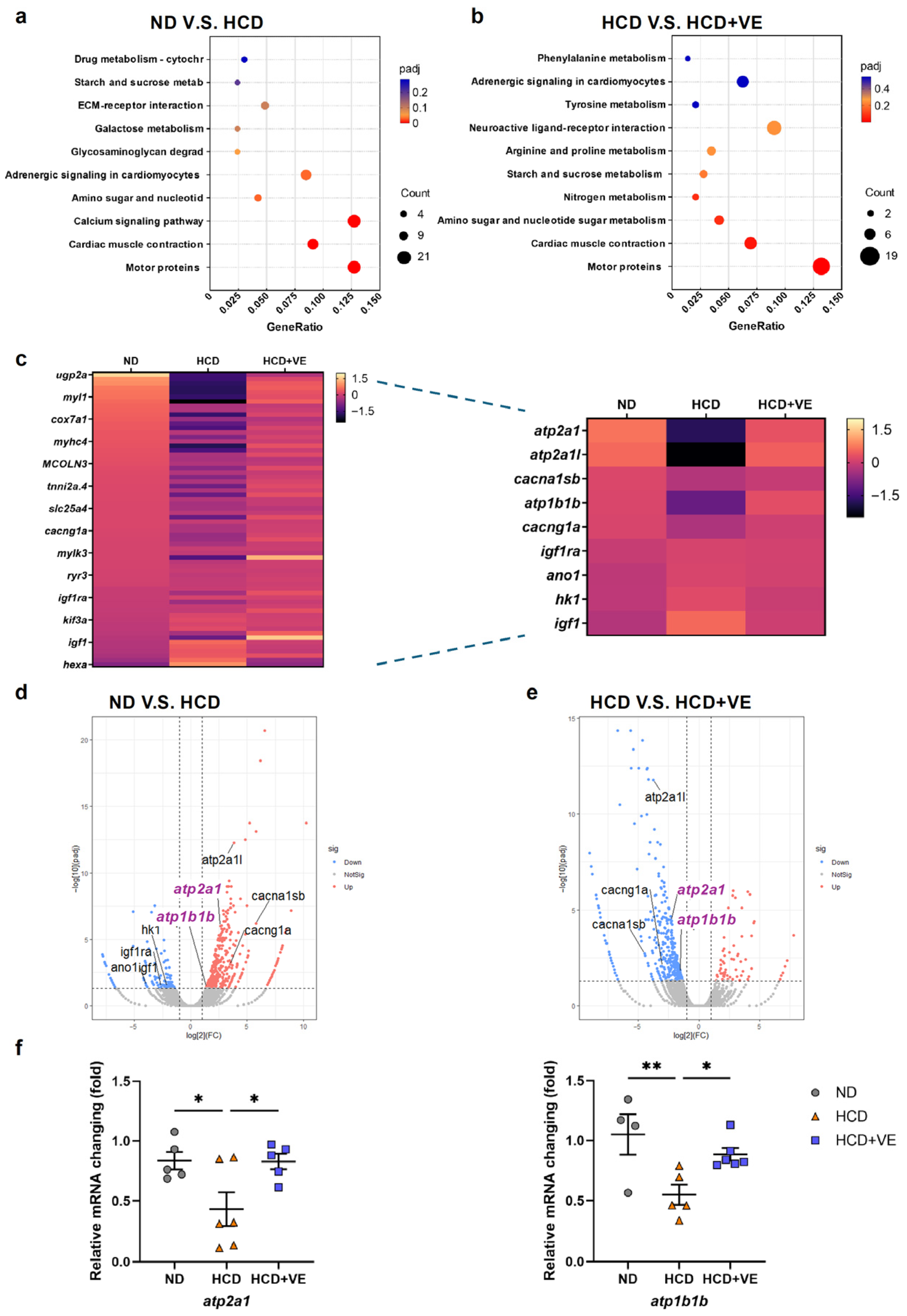

2.4. Vitamin E Modulates Intracellular Calcium-Related Gene Expression in HCD-Induced MASLD

2.5. SERCA Activation Ameliorates MASLD-like Steatosis by Reducing Hepatic eAdo Levels

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Zebrafish Maintenance

4.2. Live Imaging and GFP Detection in GRABAdo-Expressing Zebrafish

4.3. Histological Analysis

4.4. Oil Red O Staining

4.5. mRNA Sequencing

4.6. RT-PCR Analysis

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Francque, S.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kanwal, F.; Romero, D.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Anstee, Q.M.; Arab, J.P.; et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology 2023, 78, 1966–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riazi, K.; Azhari, H.; Charette, J.H.; Underwood, F.E.; King, J.A.; Afshar, E.E.; Swain, M.G.; Congly, S.E.; Kaplan, G.G.; Shaheen, A.A. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchison, A.L.; Tavaglione, F.; Romeo, S.; Charlton, M. Endocrine aspects of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): Beyond insulin resistance. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 1524–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokumaru, T.; Apolinario, M.E.C.; Shimizu, N.; Umeda, R.; Honda, K.; Shikano, K.; Teranishi, H.; Hikida, T.; Hanada, T.; Ohta, K.; et al. Hepatic extracellular ATP/adenosine dynamics in zebrafish models of alcoholic and metabolic steatotic liver disease. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, M.E. The contribution of sterile inflammation to the fatty liver disease and the potential therapies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 148, 112789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mederacke, I.; Filliol, A.; Affo, S.; Nair, A.; Hernandez, C.; Sun, Q.; Hamberger, F.; Brundu, F.; Chen, Y.; Ravichandra, A.; et al. The purinergic P2Y14 receptor links hepatocyte death to hepatic stellate cell activation and fibrogenesis in the liver. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabe5795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaner, W.S.; Shmarakov, I.O.; Traber, M.G. Vitamin A and Vitamin E: Will the Real Antioxidant Please Stand Up? Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2021, 41, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pein, H.; Ville, A.; Pace, S.; Temml, V.; Garscha, U.; Raasch, M.; Alsabil, K.; Viault, G.; Dinh, C.P.; Guilet, D.; et al. Endogenous metabolites of vitamin E limit inflammation by targeting 5-lipoxygenase. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violet, P.C.; Ebenuwa, I.C.; Wang, Y.; Niyyati, M.; Padayatty, S.J.; Head, B.; Wilkins, K.; Chung, S.; Thakur, V.; Ulatowski, L.; et al. Vitamin E sequestration by liver fat in humans. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e133309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar-Gomez, E.; Vuppalanchi, R.; Gawrieh, S.; Ghabril, M.; Saxena, R.; Cummings, O.W.; Chalasani, N. Vitamin E Improves Transplant-Free Survival and Hepatic Decompensation Among Patients With Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis and Advanced Fibrosis. Hepatology 2020, 71, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavine, J.E.; Schwimmer, J.B.; Van Natta, M.L.; Molleston, J.P.; Murray, K.F.; Rosenthal, P.; Abrams, S.H.; Scheimann, A.O.; Sanyal, A.J.; Chalasani, N.; et al. Effect of vitamin E or metformin for treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children and adolescents: The TONIC randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2011, 305, 1659–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violi, F.; Cangemi, R. Pioglitazone, vitamin E, or placebo for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 1185–1186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, T.; Yoneda, M.; Nakamura, K.; Makino, I.; Terano, A. Plasma transforming growth factor-beta1 level and efficacy of alpha-tocopherol in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: A pilot study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 15, 1667–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; He, K.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Pan, S.; Li, B.; Liu, T.; Xi, F.; Deng, F.; Wang, H.; et al. A sensitive GRAB sensor for detecting extracellular ATP in vitro and in vivo. Neuron 2022, 110, 770–782.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee-Rueckert, M.; Jauhiainen, M.; Kovanen, P.T.; Escolà-Gil, J.C. Lipids and lipoproteins in the interstitial tissue fluid regulate the formation of dysfunctional tissue-resident macrophages: Implications for atherogenic, tumorigenic, and obesogenic processes. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2025, 114, 104–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q. Different Roles of Tocopherols and Tocotrienols in Chemoprevention and Treatment of Prostate Cancer. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarski, T.K.; Rahim, M.; Hasenour, C.M.; Banerjee, D.R.; Trenary, I.A.; Wasserman, D.H.; Young, J.D. Pharmacological SERCA activation limits diet-induced steatohepatitis and restores liver metabolic function in mice. J. Lipid Res. 2024, 65, 100558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Coker, O.O.; Chu, E.S.; Fu, K.; Lau, H.C.H.; Wang, Y.X.; Chan, A.W.H.; Wei, H.; Yang, X.; Sung, J.J.Y.; et al. Dietary cholesterol drives fatty liver-associated liver cancer by modulating gut microbiota and metabolites. Gut 2021, 70, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.T.; Van Rooyen, D.M.; Koina, M.E.; McCuskey, R.S.; Teoh, N.C.; Farrell, G.C. Hepatocyte free cholesterol lipotoxicity results from JNK1-mediated mitochondrial injury and is HMGB1 and TLR4-dependent. J. Hepatol. 2014, 61, 1376–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q. Natural forms of vitamin E: Metabolism, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities and their role in disease prevention and therapy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 72, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, R.A. P2X receptors. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20150427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Su, T.P. Sigma-1 receptor chaperones at the ER-mitochondrion interface regulate Ca(2+) signaling and cell survival. Cell 2007, 131, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isshiki, M.; Ando, J.; Korenaga, R.; Kogo, H.; Fujimoto, T.; Fujita, T.; Kamiya, A. Endothelial Ca2+ waves preferentially originate at specific loci in caveolin-rich cell edges. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 5009–5014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, B.C. Phosphoinositides and intracellular calcium signaling: Novel insights into phosphoinositides and calcium coupling as negative regulators of cellular signaling. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1702–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arruda, A.P.; Hotamisligil, G.S. Calcium Homeostasis and Organelle Function in the Pathogenesis of Obesity and Diabetes. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.Y.; Chen, J.Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Lu, Y.; Dong, Z.; Liu, K.; Wang, Z.; et al. Single-cell transcriptome landscape of zebrafish liver reveals hepatocytes and immune cell interactions in understanding nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 146, 109428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingg, J.M. Finding vitamin Ex(‡). Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 211, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzi, A. Reflections on a century of vitamin E research: Looking at the past with an eye on the future. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 175, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Forward Primer (5’–3’) | Reverse Primer (5’–3’) |

|---|---|---|

| atf6 | CAGCACAGAGGCAGAACCTT | GTTCACTGCCGGGATTCTTTTC |

| bcl2a | GGGCCACTGGAAAACTGGAT | CCAAGCCGAGCACTTTTGTT |

| caspase1 | TTCTCTGATGTCGTGCACCC | ATGTGATCCTCATGTGCGCA |

| caspase3a | TTTGATCGCAGGACAGGCAT | GCGCAACTGTCTGGTCATTG |

| gapdh | CTGGTGACCCGTGCTGCTTT | GTTTGCCGCCTTCTGCCTTA |

| il1b | ACTGTTCAGATCCGCTTGCA | TCAGGGCGATGATGACGTTC |

| ire1 | GAAGGGTTGACGAAACTGCC | ATTCTGTGCGGCCAAGGTAA |

| mmp9 | CTCGTTGAGAGCCTGGTGTT | CGCTTCAGATACTCATCCGCT |

| nlrp3 | TCAGCTCTGAGTTCAAACCCC | CACCCATAGGATCAGTTTTGAGTG |

| tnfα | GCTTATGAGCCATGCAGTGA | TGCCCAGTCTGTCTCCTTCT |

| xbp1 | GGAGTTGGAGCTGGAGAATCA | TCCAACCCCAGTCTCTGTCT |

| atp2a1 | GTTGTCTCCCCTTTGAGCAG | TCCCAGATGCTCTTACCTTCTTC |

| atp1b1b | GAACTTCAGACCTAAGCCACC | CCTCACCTCACCCAGCTTAC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shan, M.; Apolinario, M.E.C.; Tokumaru, T.; Shikano, K.; Phurpa, P.; Kato, A.; Teranishi, H.; Kume, S.; Shimizu, N.; Kurokawa, T.; et al. Vitamin E Modulates Hepatic Extracellular Adenosine Signaling to Attenuate Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020614

Shan M, Apolinario MEC, Tokumaru T, Shikano K, Phurpa P, Kato A, Teranishi H, Kume S, Shimizu N, Kurokawa T, et al. Vitamin E Modulates Hepatic Extracellular Adenosine Signaling to Attenuate Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):614. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020614

Chicago/Turabian StyleShan, Mengting, Magdeline E. Carrasco Apolinario, Tomoko Tokumaru, Kenshiro Shikano, Phurpa Phurpa, Ami Kato, Hitoshi Teranishi, Shinichiro Kume, Nobuyuki Shimizu, Tatsuki Kurokawa, and et al. 2026. "Vitamin E Modulates Hepatic Extracellular Adenosine Signaling to Attenuate Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD)" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020614

APA StyleShan, M., Apolinario, M. E. C., Tokumaru, T., Shikano, K., Phurpa, P., Kato, A., Teranishi, H., Kume, S., Shimizu, N., Kurokawa, T., Hikida, T., Hanada, T., Li, Y., & Hanada, R. (2026). Vitamin E Modulates Hepatic Extracellular Adenosine Signaling to Attenuate Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020614