Prolonged QT Interval in HIV-1 Infected Humanized Mice Treated Chronically with Dolutegravir/Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate/Emtricitabine †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

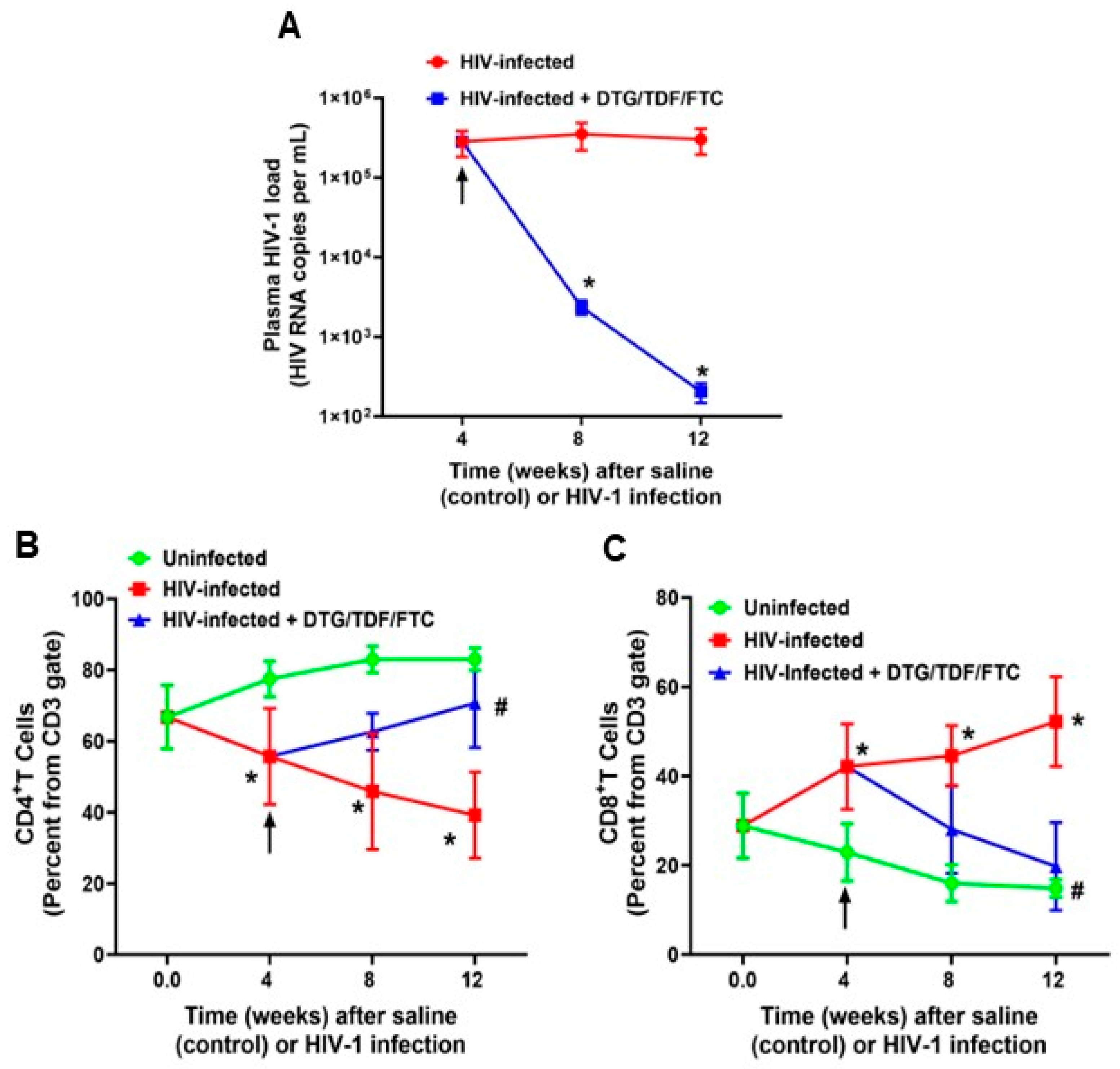

2.1. Characteristics of Animals Used in the Study

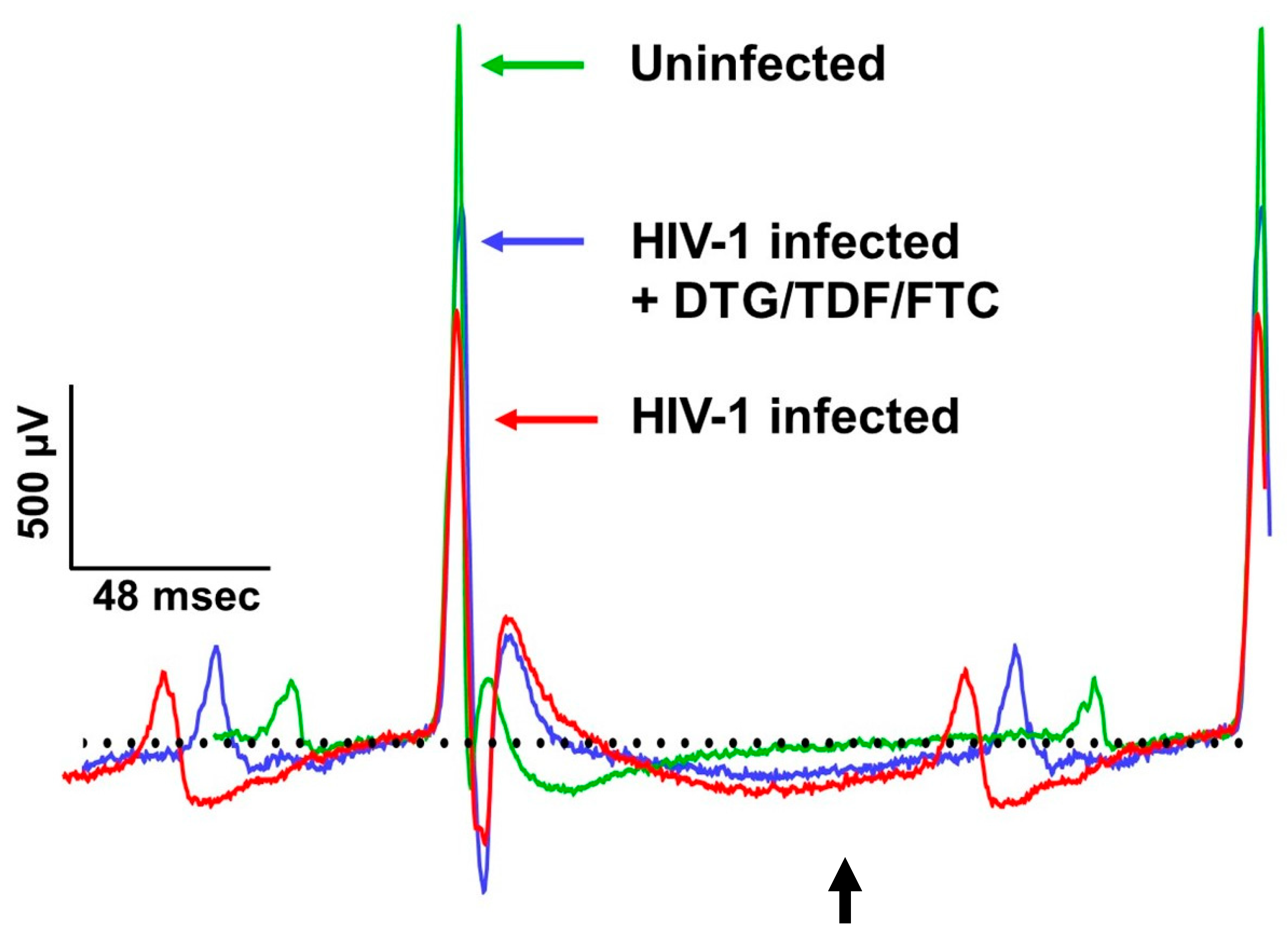

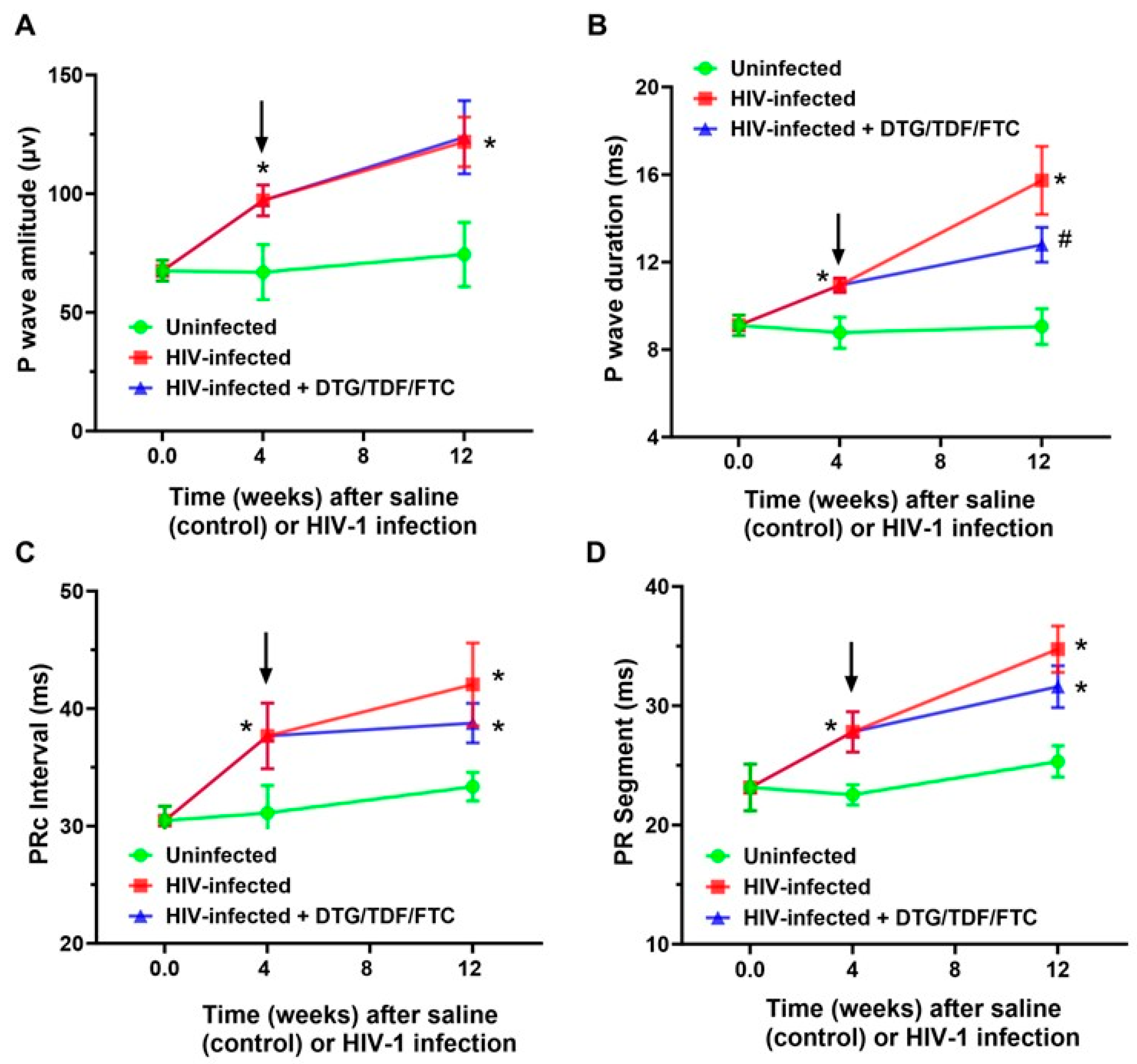

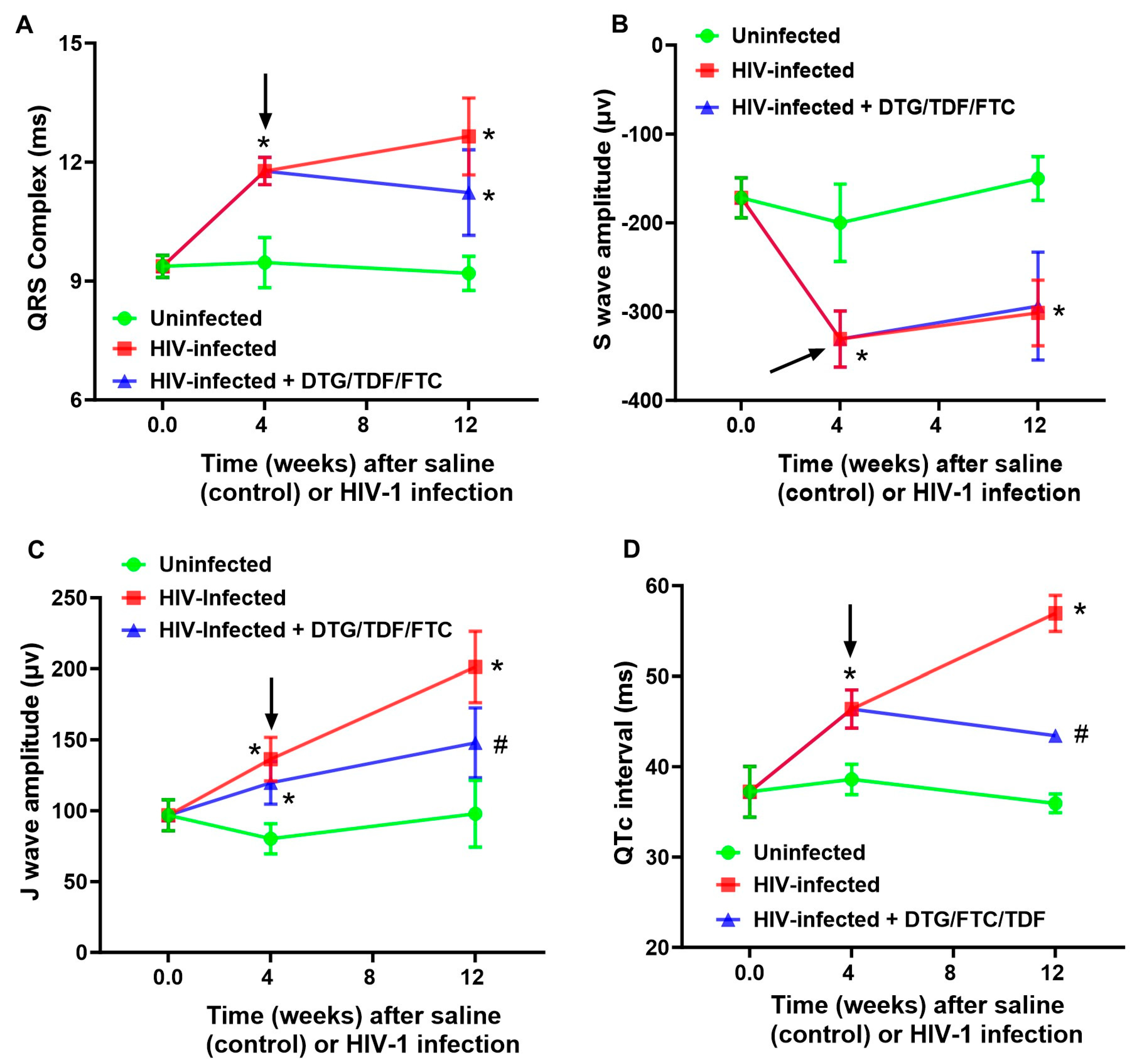

2.2. ECG Traces

2.3. Expression of RyR2, phosphoRyR2 (Ser 2808), and SERCA2

2.4. Density of Perfused Micro Vessels, Microvascular Leakage, Ischemia, and Fibrosis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethical Considerations

4.2. Antibodies and Reagents

4.3. Generation of NSG Humanized Mice

4.4. Study Protocol

4.5. Antiretroviral Treatment

4.6. Western Blotting Analysis

4.7. Density of Perfused Micro Vessels and Fibrosis

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCD | Sudden cardiac death |

| PWH | People living with HIV |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| DTG | Dolutegravir |

| TDF | Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate |

| FTC | Emtricitabine |

| SR | Sarcoplasmic reticulum |

| RyR2 | Type 2 ryanodine receptor |

| ARD | Antiretroviral drug |

| SERCA2 | Sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase |

References

- Afzal, M.; Agarwal, S.; Elshaikh, R.H.; Babker, A.M.A.; Osman, E.A.I.; Choudhary, R.K.; Jaiswal, S.; Zahir, F.; Prabhakar, P.K.; Abbas, A.M.; et al. Innovative Diagnostic Approaches and Challenges in the Management of HIV: Bridging Basic Science and Clinical Practice. Life 2025, 15, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleman, M.; Khan, S.U.; Hussain, T.; Khan, M.U.; Shamsul Hassan, S.; Majid, M.; Khan, S.U.; Shehzad Khan, M.; Shan Ahmad, R.U.; Arif, M.; et al. Cardiovascular challenges in the era of antiretroviral therapy for AIDS/ HIV: A comprehensive review of research advancements, pathophysiological insights, and future directions. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2024, 49, 102353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Wang, W.; He, J.; Duan, W.; Ma, X.; Guan, H.; Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Tian, T.; et al. Higher cardiovascular disease risks in people living with HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Glob. Health 2024, 14, 04078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, I.; Feinstein, M.J. Evolving mechanisms and presentations of cardiovascular disease in people with HIV: Implications for management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2024, 37, e0009822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsue, P.Y. Mechanisms of Cardiovascular Disease in the Setting of HIV Infection. Can. J. Cardiol. 2019, 35, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, Z.H.; Secemsky, E.A.; Dowdy, D.; Vittinghoff, E.; Moyers, B.; Wong, J.K.; Havlir, D.V.; Hsue, P.Y. Sudden cardiac death in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 59, 1891–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelazeem, B.; Gergis, K.; Baral, N.; Rauniyar, R.; Adhikari, G. Sudden Cardiac Death and Sudden Cardiac Arrest in Patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2021, 13, e13764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freiberg, M.S.; Duncan, M.S.; Alcorn, C.; Chang, C.H.; Kundu, S.; Mumpuni, A.; Smith, E.K.; Loch, S.; Bedigian, A.; Vittinghoff, E.; et al. HIV Infection and the Risk of World Health Organization-Defined Sudden Cardiac Death. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e021268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Z.H.; Moffatt, E.; Kim, A.; Vittinghoff, E.; Ursell, P.; Connolly, A.; Olgin, J.E.; Wong, J.K.; Hsue, P.Y. Sudden Cardiac Death and Myocardial Fibrosis, Determined by Autopsy, in Persons with HIV. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 2306–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvi, R.M.; Neilan, A.M.; Tariq, N.; Hassan, M.O.; Awadalla, M.; Zhang, L.; Afshar, M.; Rokicki, A.; Mulligan, C.P.; Triant, V.A.; et al. The Risk for Sudden Cardiac Death Among Patients Living With Heart Failure and Human Immunodeficiency Virus. JACC Heart Fail. 2019, 7, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierzchalski, J.; Cunnigham, N.; Kooij, K.; Guillemi, S.; Smith, R.; McCandless, L.; Hogg, R. Sudden cardiac death in adults living with HIV: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0334718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- deFilippi, C.; Awwad, A.; Bloomfield, G.S.; Weir, I.R.; Ribaudo, H.; Zanni, M.V.; Fichtenbaum, C.J.; Malvestutto, C.D.; Aberg, J.A.; Diggs, M.R.; et al. Risks for sudden cardiac and undetermined cause of death among people with HIV in the REPRIEVE primary cardiovascular prevention trial. AIDS 2025, 39, 1709–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, M.T.; Ingle, S.M. Life expectancy of HIV-positive adults: A review. Sex. Health 2011, 8, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabre, P.; Chocron, R.; Laurenceau, T.; Chabrol, M.; Meli, U.; Youssfi, Y.; Perier, M.C.; Bougouin, W.; Beganton, F.; Loeb, T.; et al. Association of human immunodeficiency virus with acute myocardial infarction and presumed sudden cardiac death. Resusc. Plus 2025, 25, 101035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Guo, W.; Wei, J.; Tang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.Z.; Tan, V.H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, R.; Jones, P.P.; et al. Identification of loss-of-function RyR2 mutations associated with idiopathic ventricular fibrillation and sudden death. Biosci. Rep. 2021, 41, BSR20210209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Es-Salah-Lamoureux, Z.; Jouni, M.; Malak, O.A.; Belbachir, N.; Al Sayed, Z.R.; Gandon-Renard, M.; Lamirault, G.; Gauthier, C.; Baro, I.; Charpentier, F.; et al. HIV-Tat induces a decrease in I(Kr) and I(Ks)via reduction in phosphatidylinositol-(4,5)-bisphosphate availability. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2016, 99, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.L.; Liu, H.B.; Sun, B.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Hu, C.W.; Zhu, J.X.; Gong, D.M.; Teng, X.; Zhang, Q.; et al. HIV Tat protein inhibits hERG K+ channels: A potential mechanism of HIV infection induced LQTs. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2011, 51, 876–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallecillo, G.; Mojal, S.; Roquer, A.; Martinez, D.; Rossi, P.; Fonseca, F.; Muga, R.; Torrens, M. Risk of QTc prolongation in a cohort of opioid-dependent HIV-infected patients on methadone maintenance therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, 1189–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, A.D.; Graff, C.; Nielsen, J.B.; Thomsen, M.T.; Hogh, J.; Benfield, T.; Gerstoft, J.; Kober, L.; Kofoed, K.F.; Nielsen, S.D. De novo electrocardiographic abnormalities in persons living with HIV. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovari, J.; Kovacs, Z.M.; Dienes, C.; Magyar, J.; Banyasz, T.; Nanasi, P.P.; Horvath, B.; Domingos, G.J.; Feher, A.; Varga, Z.; et al. Delavirdine modifies action potential configuration via inhibition of I(Kr) and I(to) in canine ventricular myocytes. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 186, 117994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.C.; Zhang, L.; Haberlen, S.A.; Ashikaga, H.; Brown, T.T.; Budoff, M.J.; D’Souza, G.; Kingsley, L.A.; Palella, F.J.; Margolick, J.B.; et al. Predictors of electrocardiographic QT interval prolongation in men with HIV. Heart 2019, 105, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, G.S.; Weir, I.R.; Ribaudo, H.J.; Fitch, K.V.; Fichtenbaum, C.J.; Moran, L.E.; Bedimo, R.; de Filippi, C.; Morse, C.G.; Piccini, J.; et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Electrocardiographic Abnormalities in Adults With HIV: Insights From the Randomized Trial to Prevent Vascular Events in HIV (REPRIEVE). J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2022, 89, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narla, V.A. Sudden cardiac death in HIV-infected patients: A contemporary review. Clin. Cardiol. 2021, 44, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouillette, J.; Cyr, S.; Fiset, C. Mechanisms of Arrhythmia and Sudden Cardiac Death in Patients With HIV Infection. Can. J. Cardiol. 2019, 35, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knudsen, A.D.; Kofoed, K.F.; Gelpi, M.; Sigvardsen, P.E.; Mocroft, A.; Kuhl, J.T.; Fuchs, A.; Kober, L.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Benfield, T.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors of prolonged QT interval and electrocardiographic abnormalities in persons living with HIV. AIDS 2019, 33, 2205–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, F.; Zhu, B.; Ding, Y.; Gao, M.; He, N. Electrocardiographic abnormalities among people with HIV in Shanghai, China. Biosci. Trends 2020, 14, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soliman, E.Z.; Prineas, R.J.; Roediger, M.P.; Duprez, D.A.; Boccara, F.; Boesecke, C.; Stephan, C.; Hodder, S.; Stein, J.H.; Lundgren, J.D.; et al. Prevalence and prognostic significance of ECG abnormalities in HIV-infected patients: Results from the Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy study. J. Electrocardiol. 2011, 44, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semulimi, A.W.; Kyazze, A.P.; Kyalo, E.; Mukisa, J.; Batte, C.; Bongomin, F.; Ssinabulya, I.; Kirenga, B.J.; Okello, E. Review of electrocardiographic abnormalities among people living with HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, M.; Venn, Z.L.; Alomar, F.A.; Namvaran, A.; Edagwa, B.; Gorantla, S.; Bidasee, K.R. Elevated Methylglyoxal: An Elusive Risk Factor Responsible for Early-Onset Cardiovascular Diseases in People Living with HIV-1 Infection. Viruses 2025, 17, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpitikul, W.B.; Dick, I.E.; Joshi-Mukherjee, R.; Overgaard, M.T.; George, A.L., Jr.; Yue, D.T. Calmodulin mutations associated with long QT syndrome prevent inactivation of cardiac L-type Ca(2+) currents and promote proarrhythmic behavior in ventricular myocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2014, 74, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Recommends Dolutegravir as Preferred HIV Treatment Option in All Populations. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/22-07-2019-who-recommends-dolutegravir-as-preferred-hiv-treatment-option-in-all-populations (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents With HIV. Available online: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/adult-and-adolescent-arv/what-start-initial-combination-regimens-antiretroviral-naive-1 (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Recommended Treatments for HIV. Available online: https://www.aidsmap.com/about-hiv/recommended-treatments-hiv (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Eron, J.J., Jr.; Lelievre, J.D.; Kalayjian, R.; Slim, J.; Wurapa, A.K.; Stephens, J.L.; McDonald, C.; Cua, E.; Wilkin, A.; Schmied, B.; et al. Safety of elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide in HIV-1-infected adults with end-stage renal disease on chronic haemodialysis: An open-label, single-arm, multicentre, phase 3b trial. Lancet HIV 2018, 6, e15–e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Buchanan, A.M.; Chen, S.; Ford, S.L.; Gould, E.; Margolis, D.; Spreen, W.R.; Patel, P. Effect of Cabotegravir on Cardiac Repolarization in Healthy Subjects. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 2016, 5, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emtricitabine/Rilpivirine/Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate Fixed-Dose Combination. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2014/P201400148/800155000_22600AMX01325_F100_1.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Iwamoto, M.; Kost, J.T.; Mistry, G.C.; Wenning, L.A.; Breidinger, S.A.; Marbury, T.C.; Stone, J.A.; Gottesdiener, K.M.; Bloomfield, D.M.; Wagner, J.A. Raltegravir thorough QT/QTc study: A single supratherapeutic dose of raltegravir does not prolong the QTcF interval. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 48, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Min, S.S.; Peppercorn, A.; Borland, J.; Lou, Y.; Song, I.; Fujiwara, T.; Piscitelli, S.C. Effect of a single supratherapeutic dose of dolutegravir on cardiac repolarization. Pharmacotherapy 2012, 32, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Duan, Y.; Xu, Q.; Wang, S.; Gao, G.; Han, N.; Zhao, H. Torsade de pointes associated with long-term antiretroviral drugs in a patient with HIV: A case report. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1268597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentini, A.; Petrosillo, N.; Di Stefano, A.; Cicalini, S.; Borgognoni, L.; Boumis, E.; Tubani, L.; Chinello, P. QTc interval prolongation in HIV-infected patients: A case-control study by 24-hour Holter ECG recording. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2012, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandy, S.A.; Brouillette, J.; Fiset, C. Reduction of ventricular sodium current in a mouse model of HIV. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2010, 21, 916–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boczek, N.J.; Gomez-Hurtado, N.; Ye, D.; Calvert, M.L.; Tester, D.J.; Kryshtal, D.; Hwang, H.S.; Johnson, C.N.; Chazin, W.J.; Loporcaro, C.G.; et al. Spectrum and Prevalence of CALM1-, CALM2-, and CALM3-Encoded Calmodulin Variants in Long QT Syndrome and Functional Characterization of a Novel Long QT Syndrome-Associated Calmodulin Missense Variant, E141G. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2016, 9, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; MacMillan, L.B.; McNeill, R.B.; Colbran, R.J.; Anderson, M.E. CaM kinase augments cardiac L-type Ca2+ current: A cellular mechanism for long Q-T arrhythmias. Am. J. Physiol. 1999, 276, H2168–H2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, Y.; Miyazaki, A.; Sakaguchi, H.; Hayama, Y.; Ebishima, N.; Negishi, J.; Noritake, K.; Miyamoto, Y.; Shimizu, W.; Aiba, T.; et al. Prominent QTc prolongation in a patient with a rare variant in the cardiac ryanodine receptor gene. Heart Vessels 2017, 32, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Demillard, L.J.; Ren, J. Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Ca(2+) Dysregulation in the Pathophysiology of Inherited Arrhythmia: An Update. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022, 200, 115059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyberg, M.T.; Stoevring, B.; Behr, E.R.; Ravn, L.S.; McKenna, W.J.; Christiansen, M. The variation of the sarcolipin gene (SLN) in atrial fibrillation, long QT syndrome and sudden arrhythmic death syndrome. Clin. Chim. Acta 2007, 375, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blayney, L.M.; Lai, F.A. Ryanodine receptor-mediated arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 123, 151–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letsas, K.P.; Prappa, E.; Bazoukis, G.; Lioni, L.; Pantou, M.P.; Gourzi, P.; Degiannis, D.; Sideris, A. A novel variant of RyR2 gene in a family misdiagnosed as congenital long QT syndrome: The importance of genetic testing. J. Electrocardiol. 2020, 60, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terentyev, D.; Rees, C.M.; Li, W.; Cooper, L.L.; Jindal, H.K.; Peng, X.; Lu, Y.; Terentyeva, R.; Odening, K.E.; Daley, J.; et al. Hyperphosphorylation of RyRs underlies triggered activity in transgenic rabbit model of LQT2 syndrome. Circ. Res. 2014, 115, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelu, M.G.; Wehrens, X.H. Sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium leak and cardiac arrhythmias. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007, 35, 952–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, A.; Liu, H.; Kang, G.J.; Feng, F.; Dudley, S.C., Jr. Reduced sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) pump activity is antiarrhythmic in ischemic cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2022, 19, 2107–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, C.C.; Mavigner, M.; Silvestri, G.; Garcia, J.V. In Vivo Models of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Persistence and Cure Strategies. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 215, S142–S151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waight, E.; Zhang, C.; Mathews, S.; Kevadiya, B.D.; Lloyd, K.C.K.; Gendelman, H.E.; Gorantla, S.; Poluektova, L.Y.; Dash, P.K. Animal models for studies of HIV-1 brain reservoirs. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2022, 112, 1285–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasler, M.F.; Speck, R.F.; Kadzioch, N.P. Humanized mice for studying HIV latency and potentially its eradication. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2024, 19, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Policicchio, B.B.; Pandrea, I.; Apetrei, C. Animal Models for HIV Cure Research. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siliciano, J.D.; Kajdas, J.; Finzi, D.; Quinn, T.C.; Chadwick, K.; Margolick, J.B.; Kovacs, C.; Gange, S.J.; Siliciano, R.F. Long-term follow-up studies confirm the stability of the latent reservoir for HIV-1 in resting CD4+ T cells. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 727–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichseldorfer, M.; Heredia, A.; Reitz, M.; Bryant, J.L.; Latinovic, O.S. Use of Humanized Mouse Models for Studying HIV-1 Infection, Pathogenesis and Persistence. J. AIDS HIV Treat. 2020, 2, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dash, P.K.; Alomar, F.A.; Hackfort, B.T.; Su, H.; Conaway, A.; Poluektova, L.Y.; Gendelman, H.E.; Gorantla, S.; Bidasee, K.R. HIV-1-Associated Left Ventricular Cardiac Dysfunction in Humanized Mice. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomar, F.A.; Dash, P.K.; Ramasamy, M.; Venn, Z.L.; Bidasee, S.R.; Zhang, C.; Hackfort, B.T.; Gorantla, S.; Bidasee, K.R. Diastolic Dysfunction with Vascular Deficits in HIV-1-Infected Female Humanized Mice Treated with Antiretroviral Drugs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulla, W.; Gillis, R.; Murninkas, M.; Klapper-Goldstein, H.; Gabay, H.; Mor, M.; Elyagon, S.; Liel-Cohen, N.; Bernus, O.; Etzion, Y. Unanesthetized Rodents Demonstrate Insensitivity of QT Interval and Ventricular Refractory Period to Pacing Cycle Length. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, G.F.; Jeron, A.; Koren, G. Measurement of heart rate and Q-T interval in the conscious mouse. Am. J. Physiol. 1998, 274, H747–H751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oestereicher, M.A.; Wotton, J.M.; Ayabe, S.; Bou About, G.; Cheng, T.K.; Choi, J.H.; Clary, D.; Dew, E.M.; Elfertak, L.; Guimond, A.; et al. Comprehensive ECG reference intervals in C57BL/6N substrains provide a generalizable guide for cardiac electrophysiology studies in mice. Mamm. Genome 2023, 34, 180–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomar, F.A.; Tian, C.; Bidasee, S.R.; Venn, Z.L.; Schroder, E.; Palermo, N.Y.; AlShabeeb, M.; Edagwa, B.J.; Payne, J.J.; Bidasee, K.R. HIV-Tat Exacerbates the Actions of Atazanavir, Efavirenz, and Ritonavir on Cardiac Ryanodine Receptor (RyR2). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, R.; Pedalino, R.P.; El-Sherif, N.; Turitto, G. Efavirenz-associated QT prolongation and Torsade de Pointes arrhythmia. Ann. Pharmacother. 2002, 36, 1006–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theerasuwipakorn, N.; Rungpradubvong, V.; Chattranukulchai, P.; Siwamogsatham, S.; Satitthummanid, S.; Apornpong, T.; Ohata, P.J.; Han, W.M.; Kerr, S.J.; Boonyaratavej, S.; et al. Higher prevalence of QTc interval prolongation among virologically suppressed older people with HIV. AIDS 2022, 36, 2153–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, K.; Hughes, C.A.; Hills-Nieminen, C. Protease inhibitor-associated QT interval prolongation. Ann. Pharmacother. 2011, 45, 1544–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D.Y.; An, S.; Romero, M.E.; Kaur, A.; Ravi, V.; Huang, H.D.; Vij, A. Incidence and risk factors of atrial fibrillation and atrial arrhythmias in people living with HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. 2022, 65, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.B.; Pietersen, A.; Graff, C.; Lind, B.; Struijk, J.J.; Olesen, M.S.; Haunso, S.; Gerds, T.A.; Ellinor, P.T.; Kober, L.; et al. Risk of atrial fibrillation as a function of the electrocardiographic PR interval: Results from the Copenhagen ECG Study. Heart Rhythm. 2013, 10, 1249–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ertem, A.G.; Yayla, C.; Acar, B.; Unal, S.; Erdol, M.A.; Sonmezer, M.C.; Kaya Kilic, E.; Ataman Hatipoglu, C.; Gokaslan, S.; Kafes, H.; et al. Assessment of the atrial electromechanical properties of patients with human immunodeficiency virus. J. Infect. Public Health 2017, 10, 721–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.; Arora, R.; Jawad, E. HIV protease inhibitors induced prolongation of the QT Interval: Electrophysiology and clinical implications. Am. J. Ther. 2010, 17, e193–e201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsuez, J.J.; Lopez-Sublet, M. Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death in Persons Living with HIV Infection. Curr. HIV Res. 2022, 20, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.C.; Woldu, B.; Post, W.S.; Hays, A.G. Prevention of heart failure, tachyarrhythmias and sudden cardiac death in HIV. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2022, 17, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terentyev, D.; Cooper, L.; Li, W.; Lu, Y.; Terentyeva, R.; Peng, X.; Koren, G. Defective Ca2+ Homeostasis Contributes to Arrhythmia in Transgenic Rabbit Model of LQT2 Syndrome. Circulation 2013, 128, A18560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Fontes, S.K.; Bautista, E.N.; Cheng, Z. Physiological and pathological roles of protein kinase A in the heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Kumar, A.M.; Waldrop, D.; Antoni, M.H.; Schneiderman, N.; Eisdorfer, C. The HPA axis in HIV-1 infection. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2002, 31, S89–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson-Papp, J.; Astha, V.; Nmashie, A.; Sharma, S.K.; Kim-Schulze, S.; Murray, J.; George, M.C.; Morgello, S.; Mueller, B.R.; Lawrence, S.A.; et al. Sympathetic function and markers of inflammation in well-controlled HIV. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2020, 7, 100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.B.; Hristova, K.; Fedacko, J.; El-Kilany, G.; Cornelissen, G. Chronic heart failure: A disease of the brain. Heart Fail. Rev. 2019, 24, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.; Terentyev, D. RyR2 Gain-of-Function and Not So Sudden Cardiac Death. Circ. Res. 2021, 129, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallas, D.; Roberts, J.D.; Sanatani, S.; Roston, T.M. Calcium Release Deficiency Syndrome: A New Inherited Arrhythmia Syndrome. Card. Electrophysiol. Clin. 2023, 15, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehnart, S.E.; Wehrens, X.H.; Laitinen, P.J.; Reiken, S.R.; Deng, S.X.; Cheng, Z.; Landry, D.W.; Kontula, K.; Swan, H.; Marks, A.R. Sudden death in familial polymorphic ventricular tachycardia associated with calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) leak. Circulation 2004, 109, 3208–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarado, F.J.; Bos, J.M.; Yuchi, Z.; Valdivia, C.R.; Hernandez, J.J.; Zhao, Y.T.; Henderlong, D.S.; Chen, Y.; Booher, T.R.; Marcou, C.A.; et al. Cardiac hypertrophy and arrhythmia in mice induced by a mutation in ryanodine receptor 2. JCI Insight 2019, 5, e126544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostas, J.A.P.; Skelding, K.A. Calcium/Calmodulin-Stimulated Protein Kinase II (CaMKII): Different Functional Outcomes from Activation, Depending on the Cellular Microenvironment. Cells 2023, 12, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddy, T.D.; Shumak, S.L.; Liu, P.P.; Barnie, A.; Seawright, S.J.; McLaughlin, P.R.; Zinman, B. The relationship of cardiac diastolic dysfunction to concurrent hormonal and metabolic status in type I diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1988, 66, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.H.; Capek, H.L.; Patel, K.P.; Wang, M.; Tang, K.; DeSouza, C.; Nagai, R.; Mayhan, W.; Periasamy, M.; Bidasee, K.R. Carbonylation contributes to SERCA2a activity loss and diastolic dysfunction in a rat model of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2011, 60, 947–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarain-Herzberg, A.; Marques, J.; Sukovich, D.; Periasamy, M. Thyroid hormone receptor modulates the expression of the rabbit cardiac sarco (endo) plasmic reticulum Ca(2+)-ATPase gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 1460–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, D.J.; Phillips, S.; McQuinn, T. Regulation of SERCA 2 expression by thyroid hormone in cultured chick embryo cardiomyocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 1996, 270, H638–H644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran, S.; Lescure, F.X.; Desailloud, R.; Douadi, Y.; Smail, A.; El Esper, I.; Arlot, S.; Schmit, J.L. Thyroid and VIH (THYVI) Group. Increased prevalence of hypothyroidism among human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: A need for screening. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 37, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.L.; Walton, C.B.; MacCannell, K.A.; Avelar, A.; Shohet, R.V. HIF-1 regulation of miR-29c impairs SERCA2 expression and cardiac contractility. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2019, 316, H554–H565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekeredjian, R.; Walton, C.B.; MacCannell, K.A.; Ecker, J.; Kruse, F.; Outten, J.T.; Sutcliffe, D.; Gerard, R.D.; Bruick, R.K.; Shohet, R.V. Conditional HIF-1alpha expression produces a reversible cardiomyopathy. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomar, F.A.; Al-Rubaish, A.; Al-Muhanna, F.; Al-Ali, A.K.; McMillan, J.; Singh, J.; Bidasee, K.R. Adeno-Associated Viral Transfer of Glyoxalase-1 Blunts Carbonyl and Oxidative Stresses in Hearts of Type 1 Diabetic Rats. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, U.; McMillan, J.; Alnouti, Y.; Gautum, N.; Smith, N.; Balkundi, S.; Dash, P.; Gorantla, S.; Martinez-Skinner, A.; Meza, J.; et al. Pharmacodynamic and antiretroviral activities of combination nanoformulated antiretrovirals in HIV-1-infected human peripheral blood lymphocyte-reconstituted mice. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 206, 1577–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorantla, S.; Makarov, E.; Finke-Dwyer, J.; Castanedo, A.; Holguin, A.; Gebhart, C.L.; Gendelman, H.E.; Poluektova, L. Links between progressive HIV-1 infection of humanized mice and viral neuropathogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 177, 2938–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichseldorfer, M.; Affram, Y.; Heredia, A.; Rikhtegaran-Tehrani, Z.; Sajadi, M.M.; Williams, S.P.; Tagaya, Y.; Benedetti, F.; Ramadhani, H.O.; Denaro, F.; et al. Combined cART including Tenofovir Disoproxil, Emtricitabine, and Dolutegravir has potent therapeutic effects in HIV-1 infected humanized mice. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Time = at Start | T= 4 Weeks | T = 8 Weeks | T = 12 Weeks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uninfected Hu-mice (n = 8, 4 males and 4 females) | 18.4 ± 1.1 | 18.9 ± 1.2 | 19.8 ± 1.2 | 19.6 ± 1.0 |

| Hu-mice infected with HIV-1ADA (n = 8, 4 males and 4 females) | 19.8 ± 0.4 | 20.7 ± 0.4 | 21.7 ± 0.1 | 19.9 ± 0.7 |

| Hu-mice infected with HIV-1ADA + DTG/TDF/FTC (n = 8, 4 males and 4 females) | 18.5 ± 1.4 | 19.7 ± 1.4 | 19.9 ± 1.4 | 19.1 ± 0.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Namvaran, A.; Garcia, J.V.; Ramasamy, M.; Nguyen, K.; Tavakkoli Ghazani, F.; Hackfort, B.T.; Dash, P.K.; Fisher, R.E.; Edagwa, B.; Gorantla, S.; et al. Prolonged QT Interval in HIV-1 Infected Humanized Mice Treated Chronically with Dolutegravir/Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate/Emtricitabine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010519

Namvaran A, Garcia JV, Ramasamy M, Nguyen K, Tavakkoli Ghazani F, Hackfort BT, Dash PK, Fisher RE, Edagwa B, Gorantla S, et al. Prolonged QT Interval in HIV-1 Infected Humanized Mice Treated Chronically with Dolutegravir/Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate/Emtricitabine. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010519

Chicago/Turabian StyleNamvaran, Ali, Julian V. Garcia, Mahendran Ramasamy, Kayla Nguyen, Farzaneh Tavakkoli Ghazani, Bryan T. Hackfort, Prasanta K. Dash, Reagan E. Fisher, Benson Edagwa, Santhi Gorantla, and et al. 2026. "Prolonged QT Interval in HIV-1 Infected Humanized Mice Treated Chronically with Dolutegravir/Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate/Emtricitabine" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010519

APA StyleNamvaran, A., Garcia, J. V., Ramasamy, M., Nguyen, K., Tavakkoli Ghazani, F., Hackfort, B. T., Dash, P. K., Fisher, R. E., Edagwa, B., Gorantla, S., & Bidasee, K. R. (2026). Prolonged QT Interval in HIV-1 Infected Humanized Mice Treated Chronically with Dolutegravir/Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate/Emtricitabine. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010519