Exosome and miRNA Content Engagement in the Physical Exercise Response: What Is Known to Date in Atheltic Horses?

Abstract

1. Introduction

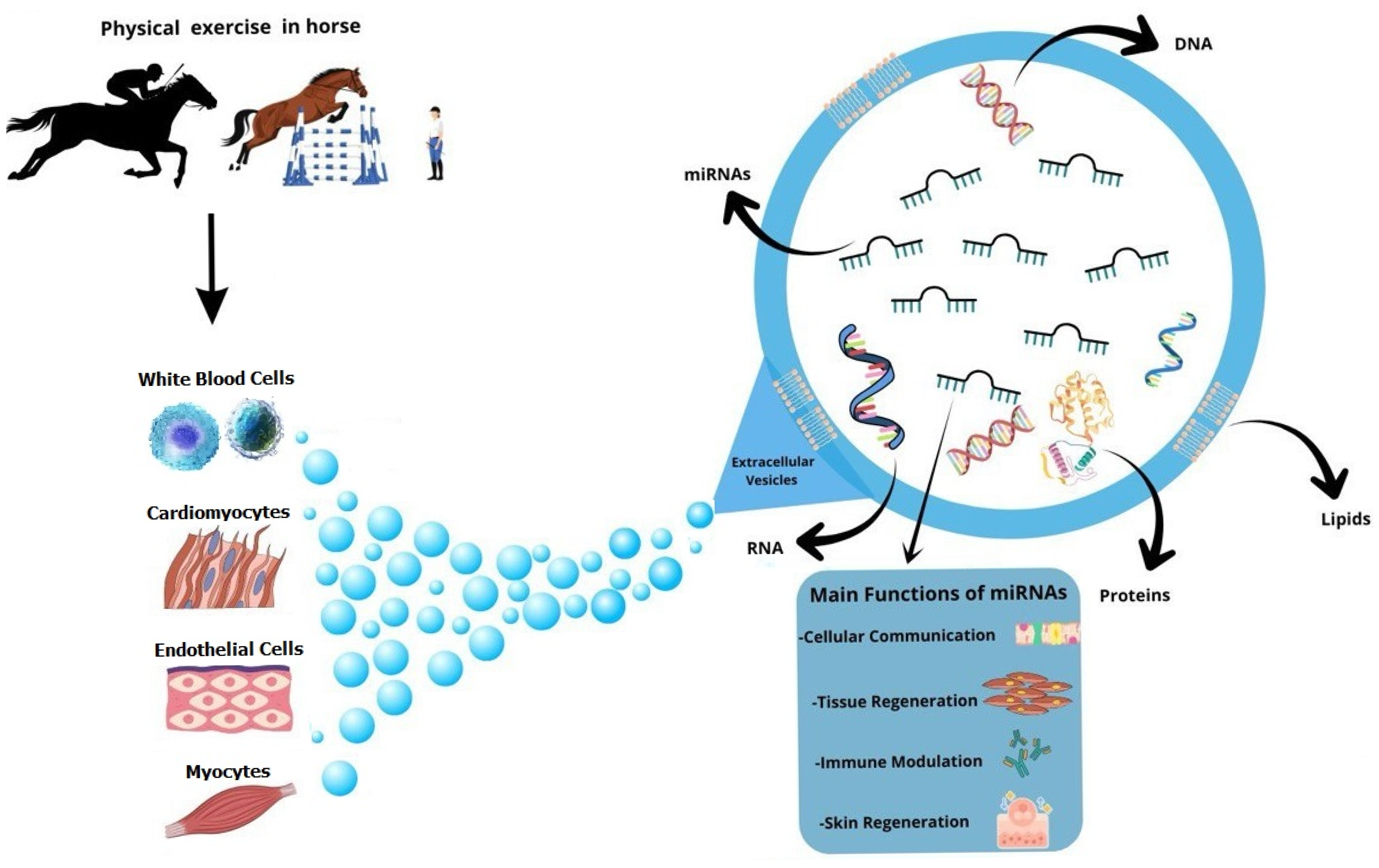

2. Literature Search Strategy

3. Cellular Vesicle Biology

3.1. Exosomes: Characteristics and Functions

3.2. Effect of Physical Exercise on Exosome Load

4. The Biological Relevance of miRNAs

5. Possible Role of miRNAs on Equine Asthma and Osteoarthritis Biology: Scientific Evidence

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| miRNAs | microRNAs |

| EVs | extracellular vesicles |

| ci-miRNA | Circulating miRNA |

| MISEV | Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles |

| ACTH | adrenocorticotropic hormone |

| IL-1Ra | interleukin-1 receptor antagonist |

| IL-1 | interleukin 1 |

| TGF-β | transforming growth factor-beta |

| IL-8 | interleukin 8 |

| IL-7 | interleukin 7 |

| IL-3 | interleukin 3 |

| IL-6 | interleukin 6 |

| IL-2 | interleukin 2 |

| IL-17 | interleukin 17 |

| IL-10 | interleukin 10 |

| MVBs | multivesicular bodies |

| ILVs | intraluminal vesicles |

| sRNA-seq | miRNA sequencing |

| GM | gluteus medius muscle |

| PSSM1 | Type 1 Polysaccharide Storage Myopathy |

| SEA | severe equine asthma |

| ASM | airway smooth muscle |

References

- Arfuso, F.; Giudice, E.; Panzera, M.; Rizzo, M.; Fazio, F.; Piccione, G.; Giannetto, C. Interleukin-1Ra (Il-1Ra) and Serum Cortisol Level Relationship in Horse as Dynamic Adaptive Response during Physical Exercise. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2022, 243, 110368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henshall, C.; Randle, H.; Francis, N.; Freire, R. The Effect of Stress and Exercise on the Learning Performance of Horses. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1918, Correction in Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfuso, F.; Assenza, A.; Fazio, F.; Rizzo, M.; Giannetto, C.; Piccione, G. Dynamic Change of Serum Levels of Some Branched-Chain Amino Acids and Tryptophan in Athletic Horses After Different Physical Exercises. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2019, 77, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellami, M.; Gasmi, M.; Denham, J.; Hayes, L.D.; Stratton, D.; Padulo, J.; Bragazzi, N. Effects of Acute and Chronic Exercise on Immunological Parameters in the Elderly Aged: Can Physical Activity Counteract the Effects of Aging? Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noakes, T.D. Physiological Models to Understand Exercise Fatigue and the Adaptations That Predict or Enhance Athletic Performance. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2000, 10, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, K. Effects of training/exercise/stress on plasma cortisol and lactate in Standardbred yearlings. J. Anim. Sci. 1987, 65, 222. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafina, L.J.; Naumov, V.A.; Cieszczyk, P.; Popov, D.V.; Lyubaeva, E.V.; Kostryukova, E.S.; Fedotovskaya, O.N.; Druzhevskaya, A.M.; Astratenkova, I.V.; Glotov, A.S.; et al. AGTR2 gene polymorphism is associated with muscle fibre composition, athletic status and aerobic performance. Exp. Physiol. 2014, 99, 1042–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogino, S.; Ogino, N.; Tomizuka, K.; Eitoku, M.; Okada, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Suganuma, N.; Ogino, K. SOD2 mRNA as a potential biomarker for exercise: Interventional and cross-sectional research in healthy subjects. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2021, 69, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Song, Y. Cardioprotective Effects of Exercise: The Role of Irisin and Exosome. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2024, 22, 316–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, S.; Tian, Z.; Boidin, M.; Buckley, B.J.R.; Thijssen, D.H.J.; Lip, G.Y.H. Irisin Is an Effector Molecule in Exercise Rehabilitation Following Myocardial Infarction (Review). Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 935772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurunathan, S.; Kang, M.-H.; Jeyaraj, M.; Qasim, M.; Kim, J.-H. Review of the Isolation, Characterization, Biological Function, and Multifarious Therapeutic Approaches of Exosomes. Cells 2019, 8, 307, Correction in Cells 2021, 10, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nederveen, J.P.; Warnier, G.; Di Carlo, A.; Nilsson, M.I.; Tarnopolsky, M.A. Extracellular Vesicles and Exosomes: Insights From Exercise Science. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 604274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frühbeis, C.; Helmig, S.; Tug, S.; Simon, P.; Krämer-Albers, E.-M. Physical Exercise Induces Rapid Release of Small Extracellular Vesicles into the Circulation. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 28239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmer, A.; Neuberger, E.; Esch-Heisser, L.; Haller, N.; Jorgensen, M.M.; Baek, R.; Möbius, W.; Simon, P.; Krämer-Albers, E.M. Platelets, endothelial cells and leukocytes contribute to the exercise-triggered release of extracellular vesicles into the circulation. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1615820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, G.; Stoorvolgel, W. Extracellular vesicles: Exosomes, macrovesicles, and friends. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 200, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, C.; Hauser, J.; Stahl, P. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of transferrin and recycling of the transferrin receptor in rat reticulocytes. J. Cell Biol. 1983, 97, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, L.J.; Sharples, R.A.; Nisbet, R.M.; Cappai, R.; Hill, A.F. The Role of Exosomes in the Processing of Proteins Associated with Neurodegenerative Diseases. Eur. Biophys. J. 2008, 37, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGivney, B.A.; Griffin, M.E.; Gough, K.F.; McGivney, C.L.; Browne, J.A.; Hill, E.W.; Katz, L.M. Evaluation of microRNA Expression in Plasma and Skeletal Muscle of Thoroughbred Racehorses in Training. BMC Vet. Res. 2017, 13, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Yao, X.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, J.; Ren, W.; Wang, T.; Li, T.; Yang, L.; Yang, X.; Meng, J. The Impact of the Competition on miRNA, Proteins, and Metabolites in the Blood Exosomes of the Yili Horse. Genes 2025, 16, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.I.; O’Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E.I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Di Vizio, D.; Driedonks, T.A.P.; Erdbrügger, U.; et al. Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles (MISEV2023): From Basic to Advanced Approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12404, Correction in J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contentin, R.; Jammes, M.; Bourdon, B.; Cassé, F.; Bianchi, A.; Audigié, F.; Branly, T.; Velot, É.; Galéra, P. Bone Marrow MSC Secretome Increases Equine Articular Chondrocyte Collagen Accumulation and Their Migratory Capacities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connard, S.S.; Gaesser, A.M.; Clarke, E.J.; Linardi, R.L.; Even, K.M.; Engiles, J.B.; Koch, D.W.; Peffers, M.J.; Ortved, K.F. Plasma and Synovial Fluid Extracellular Vesicles Display Altered microRNA Profiles in Horses with Naturally Occurring Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis: An Exploratory Study. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2024, 262, S83–S96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmer, A.; Neuberger, E.W.I.; Simon, P.; Krämer-Albers, E.-M. Considerations for the Analysis of Small Extracellular Vesicles in Physical Exercise. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 576150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdar, A.; Tarnopolsky, M.A. Exosomes as Mediators of the Systemic Adaptations to Endurance Exercise. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018, 8, a029827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bittel, D.C.; Jaiswal, J.K. Contribution of Extracellular Vesicles in Rebuilding Injured Muscles. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Familtseva, A.; Jeremic, N.; Tyagi, S.C. Exosomes: Cell-Created Drug Delivery Systems. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2019, 459, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Admyre, C.; Johansson, S.M.; Qazi, K.R.; Filén, J.-J.; Lahesmaa, R.; Norman, M.; Neve, E.P.A.; Scheynius, A.; Gabrielsson, S. Exosomes with Immune Modulatory Features Are Present in Human Breast Milk. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 1969–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegtel, D.M.; Gould, S.J. Exosomes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2019, 88, 487–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hade, M.D.; Suire, C.N.; Suo, Z. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes: Applications in Regenerative Medicine. Cells 2021, 10, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Duan, L.; Lu, J.; Xia, J. Engineering Exosomes for Targeted Drug Delivery. Theranostics 2021, 11, 3183–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masyuk, A.I.; Masyuk, T.V.; Larusso, N.F. Exosomes in the Pathogenesis, Diagnostics and Therapeutics of Liver Diseases. J. Hepatol. 2013, 59, 621–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.L. Cardiovascular Adaptations to Exercise and Training. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Equine Pract. 1985, 1, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacholewska, A.; Mach, N.; Mata, X.; Vaiman, A.; Schibler, L.; Barrey, E.; Gerber, V. Novel Equine Tissue miRNAs and Breed-Related miRNA Expressed in Serum. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, J.; Pillarisetti, S.; Junnuthula, V.; Saha, M.; Hwang, S.R.; Park, I.-K.; Lee, Y.-K. Hybrid Exosomes, Exosome-like Nanovesicles and Engineered Exosomes for Therapeutic Applications. J. Control. Release 2023, 353, 1127–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humblet, M.-F.; Vandeputte, S.; Fecher-Bourgeois, F.; Léonard, P.; Gosset, C.; Balenghien, T.; Durand, B.; Saegerman, C. Estimating the Economic Impact of a Possible Equine and Human Epidemic of West Nile Virus Infection in Belgium. Euro Surveill. 2016, 21, 30309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Lv, D.; Yang, H.; Lu, Y.; Jia, Y. A Review on the Current Literature Regarding the Value of Exosome miRNAs in Various Diseases. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 2232993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, D.; Lin, M.; Chen, J.; Cai, W.; Liu, J.; Fang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, B.; Wang, G. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α Regulates PI3K/AKT Signaling through microRNA-32-5p/PTEN and Affects Nucleus Pulposus Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeri, A.; Courtright, A.; Reiman, R.; Carlson, E.; Beecroft, T.; Janss, A.; Siniard, A.; Richholt, R.; Balak, C.; Rozowsky, J.; et al. Total Extracellular Small RNA Profiles from Plasma, Saliva, and Urine of Healthy Subjects. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, B.; Schelleckes, K.; Nedele, J.; Thorwesten, L.; Klose, A.; Lenders, M.; Krüger, M.; Brand, E.; Brand, S.-M. Dose-Response of High-Intensity Training (HIT) on Atheroprotective miRNA-126 Levels. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Sun, B.; Yin, X.; Guo, X.; Chao, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Chen, X.; Ma, J. Time-Course Responses of Circulating microRNAs to Three Resistance Training Protocols in Healthy Young Men. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soplinska, A.; Zareba, L.; Wicik, Z.; Eyileten, C.; Jakubik, D.; Siller-Matula, J.M.; De Rosa, S.; Malek, L.A.; Postula, M. MicroRNAs as Biomarkers of Systemic Changes in Response to Endurance Exercise-A Comprehensive Review. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Ma, C.; Chen, S.; Lei, W.; Yang, Y.; Liu, S.; Bihl, J.; Chen, C. Loading MiR-210 in Endothelial Progenitor Cells Derived Exosomes Boosts Their Beneficial Effects on Hypoxia/Reoxygeneation-Injured Human Endothelial Cells via Protecting Mitochondrial Function. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 46, 664–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Niel, G.; D’Angelo, G.; Raposo, G. Shedding Light on the Cell Biology of Extracellular Vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapp, R.M.; Shill, D.D.; Roth, S.M.; Hagberg, J.M. Circulating microRNAs in Acute and Chronic Exercise: More than Mere Biomarkers. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 122, 702–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denham, J.; Spencer, S.J. Emerging Roles of Extracellular Vesicles in the Intercellular Communication for Exercise-Induced Adaptations. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 319, E320–E329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, W.; Willms, E.; Hill, A.F. Understanding extracellular vesicle and nanoparticle heterogeneity: Novel methods and considerations. Proteomics 2021, 21, e2000118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- György, B.; Szatmári, R.; Ditrói, T.; Torma, F.; Pálóczi, K.; Balbisi, M.; Visnovitz, T.; Koltai, E.; Nagy, P.; Buzás, E.I.; et al. The Protein Cargo of Extracellular Vesicles Correlates with the Epigenetic Aging Clock of Exercise Sensitive DNAmFitAge. Biogerontology 2025, 26, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovett, J.; McColl, R.S.; Durcan, P.; Vechetti, I.; Myburgh, K.H. Analysis of Plasma-Derived Small Extracellular Vesicle Characteristics and microRNA Cargo Following Exercise-Induced Skeletal Muscle Damage in Men. Physiol. Rep. 2024, 12, e70056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, B.I.; Ismaeel, A.; Long, D.E.; Depa, L.A.; Coburn, P.T.; Goh, J.; Saliu, T.P.; Walton, B.J.; Vechetti, I.J.; Peck, B.D.; et al. Extracellular vesicle transfer of miR-1 to adipose tissue modifies lipolytic pathways following resistance exercise. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e182589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conkright, W.R.; Kargl, C.K.; Hubal, M.J.; Tiede, D.R.; Beckner, M.E.; Sterczala, A.J.; Krajewski, K.T.; Martin, B.J.; Flanagan, S.D.; Greeves, J.P.; et al. Acute Resistance Exercise Modifies Extracellular Vesicle miRNAs Targeting Anabolic Gene Pathways: A Prospective Cohort Study. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2024, 56, 1225–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meza, C.A.; Amador, M.; McAinch, A.J.; Begum, K.; Roy, S.; Bajpeyi, S. Eight weeks of combined exercise training do not alter circulating microRNAs-29a, -133a, -133b, and -155 in young, healthy men. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2022, 122, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horak, M.; Novak, J.; Bienertova-Vasku, J. Muscle-Specific microRNAs in Skeletal Muscle Development. Dev. Biol. 2016, 410, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawanishi, N.; Tominaga, T.; Suzuki, K. Electrical Pulse Stimulation-Induced Muscle Contraction Alters the microRNA and mRNA Profiles of Circulating Extracellular Vesicles in Mice. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2023, 324, R761–R771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mytidou, C.; Koutsoulidou, A.; Katsioloudi, A.; Prokopi, M.; Kapnisis, K.; Michailidou, K.; Anayiotos, A.; Phylactou, L.A. Muscle-Derived Exosomes Encapsulate myomiRs and Are Involved in Local Skeletal Muscle Tissue Communication. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e21279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guescini, M.; Canonico, B.; Lucertini, F.; Maggio, S.; Annibalini, G.; Barbieri, E.; Luchetti, F.; Papa, S.; Stocchi, V. Muscle Releases Alpha-Sarcoglycan Positive Extracellular Vesicles Carrying miRNAs in the Bloodstream. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, R.F.; Woodhead, J.S.T.; Zeng, N.; Blenkiron, C.; Merry, T.L.; Cameron-Smith, D.; Mitchell, C.J. Circulatory Exosomal miRNA Following Intense Exercise Is Unrelated to Muscle and Plasma miRNA Abundances. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 315, E723–E733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.-W.; Zhang, D.; Yin, H.-S.; Zhang, H.; Hong, K.-Q.; Yuan, J.-P.; Yu, B.-P. Fusobacterium Nucleatum Promotes Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Progression and Chemoresistance by Enhancing the Secretion of Chemotherapy-Induced Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype via Activation of DNA Damage Response Pathway. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2197836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mach, N.; Ramayo-Caldas, Y.; Clark, A.; Moroldo, M.; Robert, C.; Barrey, E.; López, J.M.; Le Moyec, L. Understanding the Response to Endurance Exercise Using a Systems Biology Approach: Combining Blood Metabolomics, Transcriptomics and miRNomics in Horses. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, T.; Baier, S.R.; Zempleni, J. The Intestinal Transport of Bovine Milk Exosomes Is Mediated by Endocytosis in Human Colon Carcinoma Caco-2 Cells and Rat Small Intestinal IEC-6 Cells. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 2201–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Zhu, Y.-L.; Zhou, Y.-Y.; Liang, G.-F.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Hu, F.-H.; Xiao, Z.-D. Exosome Uptake through Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis and Macropinocytosis and Mediating miR-21 Delivery. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 22258–22267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Liao, C.; Qin, J.; Gong, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, Z.; Deng, H.; Deng, W.; Sun, Q.; et al. Phosphorylation of SNX27 by MAPK11/14 Links Cellular Stress-Signaling Pathways with Endocytic Recycling. J. Cell Biol. 2021, 220, e202010048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A.P.; Lamon, S.; Boon, H.; Wada, S.; Güller, I.; Brown, E.L.; Chibalin, A.V.; Zierath, J.R.; Snow, R.J.; Stepto, N.; et al. Regulation of miRNAs in Human Skeletal Muscle Following Acute Endurance Exercise and Short-Term Endurance Training. J. Physiol. 2013, 591, 4637–4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Wang, Y.; Xie, J.; Chen, L.; Lin, X.; Lin, J.; Xiao, X. MicroRNA-30a Inhibits Cell Proliferation in a Sepsis-Induced Acute Kidney Injury Model by Targeting the YAP-TEAD Complex. J. Intensive Med. 2024, 4, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, C.-T.; Lai, W.-J.; Zhu, W.-A.; Wang, H. MicroRNA Derived from Circulating Exosomes as Noninvasive Biomarkers for Diagnosing Renal Cell Carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 10765–10774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Yin, D.; Feng, X.; He, S.; Zhang, L.; Chen, D. Bioinformatics-Based Construction of Immune-Related microRNA and mRNA Prognostic Models for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Manag. Res. 2024, 16, 1793–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinnunen, S.; Atalay, M.; Hyyppä, S.; Lehmuskero, A.; Hänninen, O.; Oksala, N. Effects of Prolonged Exercise on Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Defense in Endurance Horse. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2005, 4, 415–421. [Google Scholar]

- Greening, D.W.; Simpson, R.J. Understanding extracellular vesicle diversity—Current status. Expert Rev. Proteom. 2018, 15, 887–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitham, M.; Parker, B.L.; Friedrichsen, M.; Hingst, J.R.; Hjorth, M.; Hughes, W.E.; Egan, C.L.; Cron, L.; Watt, K.I.; Kuchel, R.P.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles Provide a Means for Tissue Crosstalk during Exercise. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 237–251.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csala, D.; Ádám, Z.; Wilhelm, M. The Role of miRNAs and Extracellular Vesicles in Adaptation After Resistance Exercise: A Review. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlemann, M.; Möbius-Winkler, S.; Fikenzer, S.; Adam, J.; Redlich, M.; Möhlenkamp, S.; Hilberg, T.; Schuler, G.C.; Adams, V. Circulating microRNA-126 Increases after Different Forms of Endurance Exercise in Healthy Adults. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2014, 21, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, S.; Kon, M.; Wada, S.; Ushida, T.; Suzuki, K.; Akimoto, T. Profiling of Circulating microRNAs after a Bout of Acute Resistance Exercise in Humans. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Kolk, J.H.; Pacholewska, A.; Gerber, V. The Role of microRNAs in Equine Medicine: A Review. Vet. Q. 2015, 35, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrey, E.; Bonnamy, B.; Barrey, E.J.; Mata, X.; Chaffaux, S.; Guerin, G. Muscular microRNA Expressions in Healthy and Myopathic Horses Suffering from Polysaccharide Storage Myopathy or Recurrent Exertional Rhabdomyolysis. Equine Vet. J. Suppl. 2010, 38, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gim, J.-A.; Ayarpadikannan, S.; Eo, J.; Kwon, Y.-J.; Choi, Y.; Lee, H.-K.; Park, K.-D.; Yang, Y.M.; Cho, B.-W.; Kim, H.-S. Transcriptional Expression Changes of Glucose Metabolism Genes after Exercise in Thoroughbred Horses. Gene 2014, 547, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, N.; Plancade, S.; Pacholewska, A.; Lecardonnel, J.; Rivière, J.; Moroldo, M.; Vaiman, A.; Morgenthaler, C.; Beinat, M.; Nevot, A.; et al. Integrated mRNA and miRNA Expression Profiling in Blood Reveals Candidate Biomarkers Associated with Endurance Exercise in the Horse. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-A.; Kim, M.-C.; Kim, N.-Y.; Ryu, D.-Y.; Lee, H.-S.; Kim, Y. Integrated Analysis of microRNA and mRNA Expressions in Peripheral Blood Leukocytes of Warmblood Horses before and after Exercise. J. Vet. Sci. 2018, 19, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, K.; Capomaccio, S.; Viglino, A.; Silvestrelli, M.; Beccati, F.; Moscati, L.; Chiaradia, E. Circulating miRNAs as Putative Biomarkers of Exercise Adaptation in Endurance Horses. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Ren, W.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, R.; Su, Y.; Huang, Q.; Dehaxi, S.; Wang, J. Comparative Analysis of miRNA Expression in Yili Horses Pre- and Post-5000-m Race. Front. Genet. 2025, 16, 1676558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akçay, S.; Gurkok-Tan, T.; Ekici, S. Identification of Key Genes in Immune-Response Post-Endurance Run in Horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2025, 149, 105418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschner, M.B.; Kao, S.C.; Edelman, J.J.; Armstrong, N.J.; Vallely, M.P.; van Zandwijk, N.; Reid, G. Haemolysis during Sample Preparation Alters microRNA Content of Plasma. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.S.; Milosevic, D.; Reddi, H.V.; Grebe, S.K.; Algeciras-Schimnich, A. Analysis of Circulating microRNA: Preanalytical and Analytical Challenges. Clin. Chem. 2011, 57, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondal, T.; Jensby Nielsen, S.; Baker, A.; Andreasen, D.; Mouritzen, P.; Wrang Teilum, M.; Dahlsveen, I.K. Assessing Sample and miRNA Profile Quality in Serum and Plasma or Other Biofluids. Methods 2013, 59, S1–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirschner, M.B.; Edelman, J.J.B.; Kao, S.C.-H.; Vallely, M.P.; van Zandwijk, N.; Reid, G. The Impact of Hemolysis on Cell-Free microRNA Biomarkers. Front. Genet. 2013, 4, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masini, A.P.; Tedeschi, D.; Badagli, P.; Sighieri, C.; Lubas, C. Exercise-induced intravascular haemolysis in standardbred horses. Comp. Clin. Path 2003, 12, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cywinska, A.; Szarska, E.; Kowalska, A.; Ostaszewski, P.; Schollenberger, A. Gender Differences in Exercise--Induced Intravascular Haemolysis during Race Training in Thoroughbred Horses. Res. Vet. Sci. 2011, 90, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R.J.A.; Olson, E.N. Control of Glucose Homeostasis and Insulin Sensitivity by the Let-7 Family of microRNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 21075–21080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardite, E.; Perdiguero, E.; Vidal, B.; Gutarra, S.; Serrano, A.L.; Muñoz-Cánoves, P. PAI-1-Regulated miR-21 Defines a Novel Age-Associated Fibrogenic Pathway in Muscular Dystrophy. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 196, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guess, M.G.; Barthel, K.K.B.; Harrison, B.C.; Leinwand, L.A. miR-30 Family microRNAs Regulate Myogenic Differentiation and Provide Negative Feedback on the microRNA Pathway. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Qi, J.; Meng, S.; Wen, B.; Zhang, J. Swimming Exercise Training-Induced Left Ventricular Hypertrophy Involves microRNAs and Synergistic Regulation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2013, 113, 2473–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.A.; Wagner, A.L.; McGlynn, O.F.; Kharazyan, F.; Browne, J.A.; Elliott, J.A. Exercise Influences Circadian Gene Expression in Equine Skeletal Muscle. Vet. J. 2014, 201, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, L.; Hou, N.; Song, Y.; An, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, J. miR-199-Sponge Transgenic Mice Develop Physiological Cardiac Hypertrophy. Cardiovasc. Res. 2016, 110, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, J.-K. The Functional Analysis of MicroRNAs Involved in NF-κB Signaling. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 20, 1764–1774. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rudnicki, A.; Shivatzki, S.; Beyer, L.A.; Takada, Y.; Raphael, Y.; Avraham, K.B. microRNA-224 Regulates Pentraxin 3, a Component of the Humoral Arm of Innate Immunity, in Inner Ear Inflammation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 3138–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scisciani, C.; Vossio, S.; Guerrieri, F.; Schinzari, V.; De Iaco, R.; D’Onorio de Meo, P.; Cervello, M.; Montalto, G.; Pollicino, T.; Raimondo, G.; et al. Transcriptional Regulation of miR-224 Upregulated in Human HCCs by NFκB Inflammatory Pathways. J. Hepatol. 2012, 56, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.; Wu, L.; Tan, J.; Zhang, B.; Tai, W.C.; Xiong, S.; Chen, W.; Yang, J.; Li, H. MiR-1180 Promotes Apoptotic Resistance to Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Activation of NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilsher, S.; Allen, W.R.; Wood, J.L. Factors associated with failure of thoroughbred horses to train and race. Equine Vet. J. 2006, 38, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khalili, L.; Bouzakri, K.; Glund, S.; Lönnqvist, F.; Koistinen, H.A.; Krook, A. Signaling Specificity of Interleukin-6 Action on Glucose and Lipid Metabolism in Skeletal Muscle. Mol. Endocrinol. 2006, 20, 3364–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Chen, J.; Qiu, H. Novel Mechanisms of Exercise-Induced Cardioprotective Factors in Myocardial Infarction. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milczek-Haduch, D.; Żmigrodzka, M.; Witkowska-Piłaszewicz, O. Extracellular Vesicles in Sport Horses: Potential Biomarkers and Modulators of Exercise Adaptation and Therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.; Liang, J.; Zhang, J.; Mao, Y.; Zheng, X.; Shen, X.; Lin, W.; Xu, G. Exosomes as a Delivery Tool of Exercise-Induced Beneficial Factors for the Prevention and Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1190095, Correction in Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1371224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulliger, M.F.; Pacholewska, A.; Vargas, A.; Lavoie, J.-P.; Leeb, T.; Gerber, V.; Jagannathan, V. An Integrative miRNA-mRNA Expression Analysis Reveals Striking Transcriptomic Similarities between Severe Equine Asthma and Specific Asthma Endotypes in Humans. Genes 2020, 11, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hupin, D.; Edouard, P.; Gremeaux, V.; Garet, M.; Celle, S.; Pichot, V.; Maudoux, D.; Barthélémy, J.C.; Roche, F. Physical Activity to Reduce Mortality Risk. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 1534–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halama, A.; Oliveira, J.M.; Filho, S.A.; Qasim, M.; Achkar, I.W.; Johnson, S.; Suhre, K.; Vinardell, T. Metabolic Predictors of Equine Performance in Endurance Racing. Metabolites 2021, 11, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, A.; Mainguy-Seers, S.; Boivin, R.; Lavoie, J.-P. Low Levels of microRNA-21 in Neutrophil-Derived Exosomes May Contribute to Airway Smooth Muscle Hyperproliferation in Horses with Severe Asthma. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2024, 85, ajvr.23.11.0267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, S.F.C.; Guest, P.C. Multiplex Analyses Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1546, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issouf, M.; Vargas, A.; Boivin, R.; Lavoie, J.-P. MicroRNA-221 Is Overexpressed in the Equine Asthmatic Airway Smooth Muscle and Modulates Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2019, 317, L748–L757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Chen, J.-Y.; Peng, W.-M.; Yuan, B.; Bi, Q.; Xu, Y.-J. Exosomes from Adipose-derived Stem Cells Promote Chondrogenesis and Suppress Inflammation by Upregulating miR-145 and miR-221. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 21, 1881–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.; Ryan, A.E.; Griffin, M.D.; Ritter, T. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: Toward Cell-Free Therapeutic Applications. Mol. Ther. 2015, 23, 812–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Record, M.; Carayon, K.; Poirot, M.; Silvente-Poirot, S. Exosomes as New Vesicular Lipid Transporters Involved in Cell-Cell Communication and Various Pathophysiologies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1841, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klymiuk, M.C.; Speer, J.; Marco, I.D.; Elashry, M.I.; Heimann, M.; Wenisch, S.; Arnhold, S. Determination of the miRNA Profile of Extracellular Vesicles from Equine Mesenchymal Stem Cells after Different Treatments. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, C.; Merli, G.; Zini, N.; D’Adamo, S.; Cattini, L.; Guescini, M.; Grigolo, B.; Di Martino, A.; Santi, S.; Borzì, R.M.; et al. Small Extracellular Vesicles from Inflamed Adipose Derived Stromal Cells Enhance the NF-κB-Dependent Inflammatory/Catabolic Environment of Osteoarthritis. Stem Cells Int. 2022, 2022, 9376338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Crawford, R.; Mao, X.; Prasadam, I. Extracellular Vesicles: Potential Role in Osteoarthritis Regenerative Medicine. J. Orthop. Translat. 2020, 21, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Equine miRNAs with Known Functions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA ID | Tissue | Function | Reference |

| miRNA-21 | Myeloid | Hyperproliferation of the smooth muscles of the airways | Vargas et al. [104] |

| miRNA-26 a | Muscle | Upregulation in the ASM of horses with asthma | Issouf et al. [106] |

| miRNA-133 | Muscle | Upregulation in the ASM of horses with asthma | Issouf et al. [106] |

| miRNA-221 | Muscle | Upregulation in the ASM of horses with asthma-induced cell hyperproliferation and reduced expression of genetic markers in ASM cells | Issouf et al. [106] |

| miRNA-122 | Liver | Regulation of energy metabolism | Pacholewska et al. [33] |

| miRNA-200 | Blood (serum) | Regulation of energy metabolism | Pacholewska et al. [33] |

| miRNA-133 b | Muscle | Differentation and proliferation of myoblasts | Pacholewska et al. [33] |

| miRNA-206 | Muscle | Differentation and proliferation of myoblasts | Pacholewska et al. [33] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sisia, G.; Giudice, E.; Attanzio, A.; Briglia, M.; Piccione, G.; Trunfio, C.; Arfuso, F. Exosome and miRNA Content Engagement in the Physical Exercise Response: What Is Known to Date in Atheltic Horses? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010520

Sisia G, Giudice E, Attanzio A, Briglia M, Piccione G, Trunfio C, Arfuso F. Exosome and miRNA Content Engagement in the Physical Exercise Response: What Is Known to Date in Atheltic Horses? International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010520

Chicago/Turabian StyleSisia, Giulia, Elisabetta Giudice, Alessandro Attanzio, Marilena Briglia, Giuseppe Piccione, Caterina Trunfio, and Francesca Arfuso. 2026. "Exosome and miRNA Content Engagement in the Physical Exercise Response: What Is Known to Date in Atheltic Horses?" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010520

APA StyleSisia, G., Giudice, E., Attanzio, A., Briglia, M., Piccione, G., Trunfio, C., & Arfuso, F. (2026). Exosome and miRNA Content Engagement in the Physical Exercise Response: What Is Known to Date in Atheltic Horses? International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010520