Mapping the Ischemic Continuum: Dynamic Multi-Omic Biomarker and AI for Personalized Stroke Care

Abstract

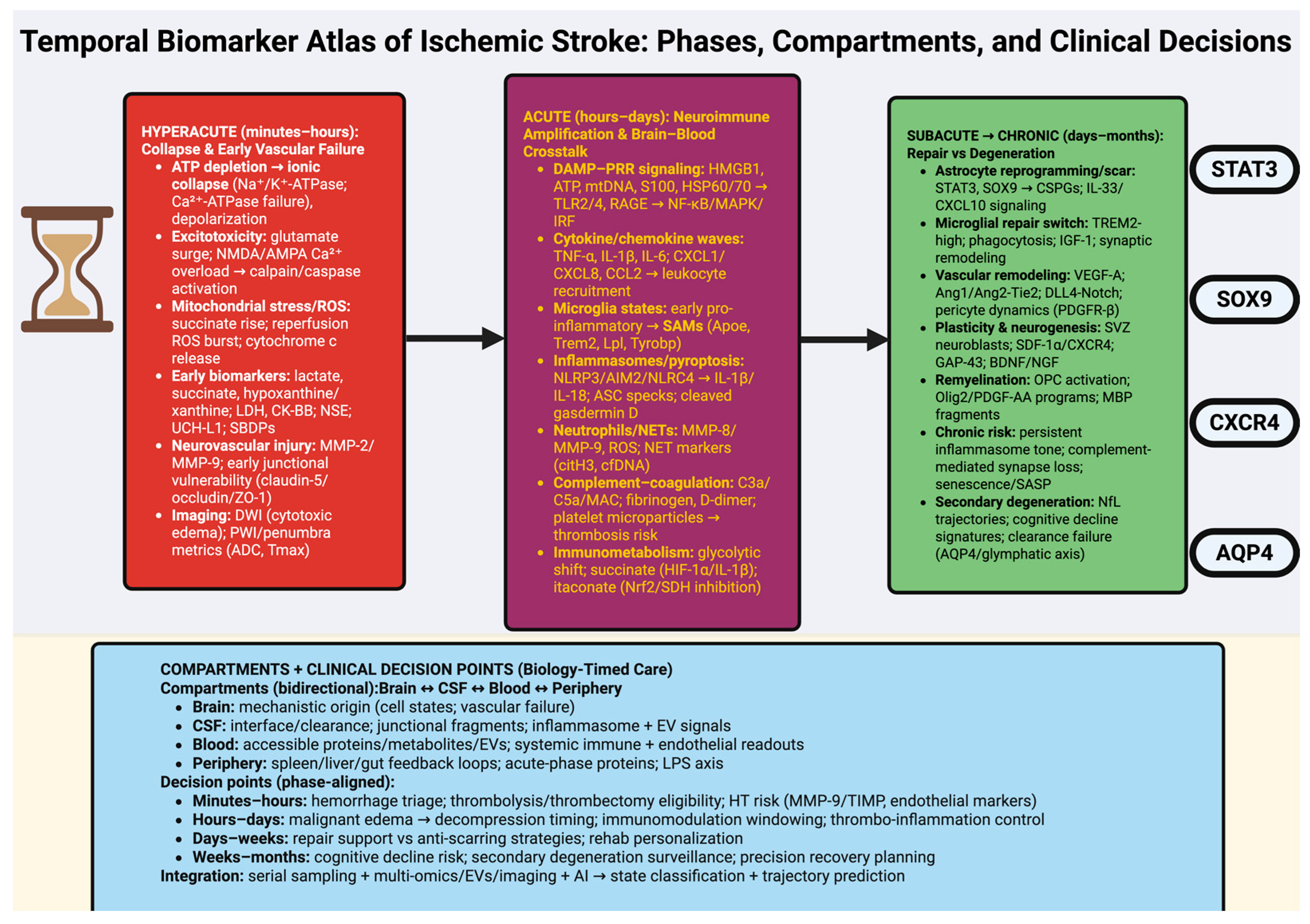

1. Introduction—Rethinking Stroke Biomarkers as Dynamic Biological Signatures

2. Hyperacute Phase (Minutes–Hours): Ischemic Collapse and Vascular Failure

2.1. Metabolic Collapse and Excitotoxic Storm: The Molecular Origin of Ischemic Injury

2.2. Neurovascular Unit Breakdown: Endothelial Dysfunction and Blood–Brain Barrier Failure

2.3. Translational Biomarker Landscape: Multi-Omics Signatures, Emerging Technologies, and Future Directions

Concluding Perspective

3. Acute Phase (Hours–Days): Neuroimmune Activation and Brain–Blood Crosstalk

3.1. Innate Immune Activation and Neuroinflammatory Cascades

3.2. Blood–Brain Barrier Dynamics and Systemic Crosstalk

3.3. Biomarker Landscape and Translational Implications

4. Subacute Phase (Days–Weeks): Glial Remodeling and Reparative Microenvironments

4.1. Astroglial and Microglial Remodeling: Orchestrators of Tissue Repair

4.2. Angiogenesis, Neurogenesis, and Network Reorganization

5. Chronic Phase (Weeks–Months): Plasticity, Maladaptation, and Long-Term Biomarker Signatures

5.1. Network-Level Plasticity and Epigenetic Remodeling

5.2. Maladaptive Remodeling, Secondary Degeneration, and Cognitive Decline

5.3. Long-Term Biomarker Signatures and Precision Therapeutic Windows

Perspective

6. Biomarkers Across Biological Compartments: From Brain Tissue to Blood and CSF

6.1. Central Biomarkers: Brain Tissue and Interstitial Fluid

6.2. Cerebrospinal Fluid: The Molecular Interface of Brain and Periphery

6.3. Peripheral Biomarkers: Translating Central Pathology into Accessible Signals

Reflections and Outlook

7. Emerging Technologies and AI-Driven Biomarker Discovery

7.1. Frontier Technologies for Biomarker Discovery

7.2. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Biomarker Analysis

7.3. Toward Predictive and Personalized Stroke Medicine

8. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gou, R.; Luo, C.; Liang, X.; Qin, S.; Wu, H.; Li, B.; Pan, F.; Li, J.; Chen, J.-A. Elderly stroke burden: A comprehensive global study over three decades. Front. Aging 2025, 6, 1489914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroudis, I.; Petridis, F.; Kazis, D.; Ciobica, A.; Dăscălescu, G.; Petroaie, A.D.; Dobrin, I.; Novac, O.; Vata, I.; Novac, B. The Diagnostic and Prognostic Role of Biomarkers in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: An Umbrella Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.-X.; Song, W.-J.; Wu, Z.-Q.; Goyal, H.; Xu, H.-G. Association of Serum Neuron-Specific Enolase and C-Reactive Protein with Disease Location and Endoscopic Inflammation Degree in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 663920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, P.; Ding, L.; Zhu, J.; Qi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xia, X.; Zheng, J.C. Circulating extracellular vesicle-containing microRNAs reveal potential pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 955511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, G.K.; Ramadan, H.K.-A.; Khedr, E.M. Short- and long-term psychiatric complications of COVID-19. Egypt. J. Neurol. Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2025, 61, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babić, A.; Bonifačić, D.; Komen, V.; Kovačić, S.; Mamić, M.; Vuletić, V. Blood Biomarkers in Ischemic Stroke Diagnostics and Treatment—Future Perspectives. Medicina 2025, 61, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Xiong, W.; Fu, L.; Yi, J.; Yang, J. Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) in diseases: Implications for therapy. Mol. Biomed. 2025, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denes, A.; Coutts, G.; Lénárt, N.; Cruickshank, S.M.; Pelegrin, P.; Skinner, J.; Rothwell, N.; Allan, S.M.; Brough, D. AIM2 and NLRC4 inflammasomes contribute with ASC to acute brain injury independently of NLRP3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 4050–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Hu, M.; Zhang, B.; Lin, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Men, X.; Lu, Z.; Cai, W. Temporal and Spatial Dynamics of Inflammasome Activation After Ischemic Stroke. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 621555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, M.; Sharma, M.; Das, B. The Role of Inflammatory Cascade and Reactive Astrogliosis in Glial Scar Formation Post-spinal Cord Injury. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 44, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltramo, E.; Mazzeo, A.; Porta, M. Release of Pro-Inflammatory/Angiogenic Factors by Retinal Microvascular Cells Is Mediated by Extracellular Vesicles Derived from M1-Activated Microglia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss Bimbova, K.; Bacova, M.; Kisucka, A.; Gálik, J.; Ileninova, M.; Kuruc, T.; Magurova, M.; Lukacova, N. Impact of Endurance Training on Regeneration of Axons, Glial Cells, and Inhibitory Neurons after Spinal Cord Injury: A Link between Functional Outcome and Regeneration Potential within the Lesion Site and in Adjacent Spinal Cord Tissue. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonangeli, F.; Arcuri, E.; Santoni, A. Cellular senescence in the innervated niche modulates cancer-associated pain: An emerging therapeutic target? Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1694567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepacki, H.; Kowalczuk, K.; Łepkowska, N.; Hermanowicz, J.M. Molecular Regulation of SASP in Cellular Senescence: Therapeutic Implications and Translational Challenges. Cells 2025, 14, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuźniar, J.; Kozubek, P.; Czaja, M.; Sitka, H.; Kochman, U.; Leszek, J. Connections Between Cellular Senescence and Alzheimer’s Disease—A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S.; Grillo, A.R.; Scarpa, M.; Brun, P.; D’Incà, R.; Nai, L.; Banerjee, A.; Cavallo, D.; Barzon, L.; Palù, G.; et al. MiR-155 modulates the inflammatory phenotype of intestinal myofibroblasts by targeting SOCS1 in ulcerative colitis. Exp. Mol. Med. 2015, 47, e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gryka-Marton, M.; Grabowska, A.D.; Szukiewicz, D. Breaking the Barrier: The Role of Proinflammatory Cytokines in BBB Dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.-H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.-H.; Wang, Y.-F.; Wang, M.-Y.; Pan, X.-R.; Zhang, Y.-D.; Gan, Y.-H.; He, Y.; Xie, F.; et al. Integrated omics identifies molecular networks of brain-body interactions of brain injury. iScience 2025, 28, 113103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killingsworth, B.; Welsh, J.A.; Jones, J.C. EV Translational Horizons as Viewed Across the Complex Landscape of Liquid Biopsies. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 556837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Han, T.; Yu, A.C.H.; Xu, L. Mechanistic understanding the bioeffects of ultrasound-driven microbubbles to enhance macromolecule delivery. J. Control. Release 2018, 272, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagonnier, M.; Donnan, G.A.; Davis, S.M.; Dewey, H.M.; Howells, D.W. Acute Stroke Biomarkers: Are We There Yet? Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 619721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Tong, Y.; Li, L.; Xu, Y.; Wu, S. Advances in the detection of biomarkers for ischemic stroke. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1488726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalia, L.; Qonitah, P. Clinical and epidemiological overview of hyperacute ischemic stroke patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis. Egypt. J. Intern. Med. 2025, 37, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahorewala, S.; Panda, C.S.; Aguilar, K.; Morera, D.S.; Zhu, H.; Gramer, A.L.; Bhuiyan, T.; Nair, M.; Barrett, A.; Bollag, R.J.; et al. Novel Molecular Signatures Selectively Predict Clinical Outcomes in Colon Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaudeen, M.A.; Bello, N.; Danraka, R.N.; Ammani, M.L. Understanding the Pathophysiology of Ischemic Stroke: The Basis of Current Therapies and Opportunity for New Ones. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belov Kirdajova, D.; Kriska, J.; Tureckova, J.; Anderova, M. Ischemia-Triggered Glutamate Excitotoxicity from the Perspective of Glial Cells. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielecińska, A.; Kciuk, M.; Kontek, R. The Impact of Calcium Overload on Cellular Processes: Exploring Calcicoptosis and Its Therapeutic Potential in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.T.; Singh, A.A.; Bang, N.V.; Vu, N.M.H.; Na, S.; Choi, J.; Oh, J.; Mondal, S. Mitochondria-Associated Membrane Dysfunction in Neurodegeneration and Its Effects on Lipid Metabolism, Calcium Signaling, and Cell Fate. Membranes 2025, 15, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hou, J.; Jiang, M.; Lei, S.; Zhao, B.; Xia, Z. Lactate Provides Metabolic Substrate Support and Attenuates Ischemic Brain Injury in Mice, Revealed by 1H-13C Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Metabolic Technique. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Muramatsu, R.; Maedera, N.; Tsunematsu, H.; Hamaguchi, M.; Koyama, Y.; Kuroda, M.; Ono, K.; Sawada, M.; Yamashita, T. Extracellular Lactate Dehydrogenase A Release From Damaged Neurons Drives Central Nervous System Angiogenesis. eBioMedicine 2017, 27, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schallerer, C.; Neuschmid, S.; Ehrlich, B.E.; McGuone, D. Calpain in Traumatic Brain Injury: From Cinderella to Central Player. Cells 2025, 14, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baez, S.D.L.C.; García del Barco, D.; Hardy-Sosa, A.; Guillen Nieto, G.; Bringas-Vega, M.L.; Llibre-Guerra, J.J.; Valdes-Sosa, P. Scalable Bio Marker Combinations for Early Stroke Diagnosis: A Systematic Review. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 638693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omari Shekaftik, S.; Nasirzadeh, N. 8-Hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) as a biomarker of oxidative DNA damage induced by occupational exposure to nanomaterials: A systematic review. Nanotoxicology 2021, 15, 850–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Zhang, S. Hypoxia inducible factor-1α/vascular endothelial growth factor signaling activation correlates with response to radiotherapy and its inhibition reduces hypoxia-induced angiogenesis in lung cancer. J. Cell. Biochem. 2018, 119, 7707–7718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asl, E.R.; Hosseini, S.E.; Tahmasebi, F.; Bolandi, N.; Barati, S. MiR-124 and MiR-155 as Therapeutic Targets in Microglia-Mediated Inflammation in Multiple Sclerosis. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 45, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.-Y.; Guo, Z.-N.; Zhang, D.-H.; Qu, Y.; Jin, H. The Role of Pericytes in Ischemic Stroke: Fom Cellular Functions to Therapeutic Targets. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 866700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottarelli, A.; Jamoul, D.; Tuohy, M.C.; Shahriar, S.; Glendinning, M.; Prochilo, G.; Edinger, A.L.; Arac, A.; Agalliu, D. Rab7a is required to degrade select blood-brain barrier junctional proteins after ischemic stroke. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2025, 13, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, E.A.; Mallard, C.; Ek, C.J. Circulating tight-junction proteins are potential biomarkers for blood–brain barrier function in a model of neonatal hypoxic/ischemic brain injury. Fluids Barriers CNS 2021, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbah, A.S.; Elkattan, M.M.; Labib, D.M.; Hamdy, M.S.E.; Wahdan, N.S.; Aboulfotoh, A.M. Role of Von Willebrand factor level as a biomarker in acute ischemic stroke. Egypt. J. Neurol. Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2024, 60, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benarroch, E. What Are the Roles of Pericytes in the Neurovascular Unit and Its Disorders? Neurology 2023, 100, 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, D.-I.; Buleu, F.; Iancu, A.; Tudor, A.; Williams, C.G.; Sutoi, D.; Marza, A.M.; Trebuian, C.I.; Cîndrea, A.C.; Militaru, M.; et al. Performance of GFAP and UCH-L1 for Early Acute Stroke Diagnosis in the Emergency Department. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, L.B.; Abdelazim, H.; Hoque, M.; Barnes, A.; Mironovova, Z.; Willi, C.E.; Darden, J.; Houk, C.; Sedovy, M.W.; Johnstone, S.R.; et al. A Soluble Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor-β Originates via Pre-mRNA Splicing in the Healthy Brain and Is Upregulated during Hypoxia and Aging. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, R.; Basak, S.; Chowdhury, P.; Bhowmik, P.; Das, R.K.; Banerjee, A.; Paul, S.; Pathak, S.; Duttaroy, A.K. Targeting Cytokine-Mediated Inflammation in Brain Disorders: Developing New Treatment Strategies. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamailova, S.; Dalla Vecchia, L.; Auer, E.; Castigliego, P.; Ziegler, V.; Fluri, M.; Boronylo, A.; Kielkopf, M.C.; Hakim, A.; Mujanovic, A.; et al. Focal Hypoperfusion on Baseline Perfusion-Weighted MRI and the Risk of Subsequent Cerebrovascular Events in Patients with TIA. Neurology 2025, 105, e213930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, X.; Wang, Y.; Luan, M.; Zhang, Y. Multi-omics and single-cell approaches reveal molecular subtypes and key cell interactions in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1605162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Ge, S.; Liao, T.; Yuan, M.; Qian, W.; Chen, Q.; Liang, W.; Cheng, X.; Zhou, Q.; Ju, Z.; et al. Integrative single-cell metabolomics and phenotypic profiling reveals metabolic heterogeneity of cellular oxidation and senescence. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbaizar-Rovirosa, M.; Gallizioli, M.; Lozano, J.J.; Sidorova, J.; Pedragosa, J.; Figuerola, S.; Chaparro-Cabanillas, N.; Boya, P.; Graupera, M.; Claret, M.; et al. Transcriptomics and translatomics identify a robust inflammatory gene signature in brain endothelial cells after ischemic stroke. J. Neuroinflamm. 2023, 20, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.A.; Baba, S.K.; Sadida, H.Q.; Marzooqi, S.A.; Jerobin, J.; Altemani, F.H.; Algehainy, N.; Alanazi, M.A.; Abou-Samra, A.-B.; Kumar, R.; et al. Extracellular vesicles as tools and targets in therapy for diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinkhani, B.; Duran, G.; Hoeks, C.; Hermans, D.; Schepers, M.; Baeten, P.; Poelmans, J.; Coenen, B.; Bekar, K.; Pintelon, I.; et al. Cerebral microvascular endothelial cell-derived extracellular vesicles regulate blood − brain barrier function. Fluids Barriers CNS 2023, 20, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Kim, C.; Gwon, D.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Park, K.M.; Park, S. Combining clinical and imaging data for predicting functional outcomes after acute ischemic stroke: An automated machine learning approach. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Pan, D.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Yan, J.; Wang, L.; Yang, X.; Yang, M.; Liu, G. Applications of multi-omics analysis in human diseases. MedComm 2023, 4, e315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, S.; Sylaja, P.N.; Sreedharan, S.E.; Singh, G.; Damayanthi, D.; Gopala, S.; Madhusoodanan, U.; Ramachandran, H. Biomarkers predict hemorrhagic transformation and stroke severity after acute ischemic stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2023, 32, 106875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, L.M.B.; Dam, V.S.; Guldbrandsen, H.Ø.; Staehr, C.; Pedersen, T.M.; Kalucka, J.M.; Beck, H.C.; Postnov, D.D.; Lin, L.; Matchkov, V.V. Spatial Transcriptomics and Proteomics Profiling After Ischemic Stroke Reperfusion: Insights Into Vascular Alterations. Stroke 2025, 56, 1036–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, M.; Lizama, B.N.; Chu, C.T. Excitotoxicity, calcium and mitochondria: A triad in synaptic neurodegeneration. Transl. Neurodegener. 2022, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicosia, N.; Giovenzana, M.; Misztak, P.; Mingardi, J.; Musazzi, L. Glutamate-Mediated Excitotoxicity in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Neurodevelopmental and Adult Mental Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Ma, Z.; Li, F.; Duan, C.; Yuan, Y.; Zhu, C.; Wang, L.; Zhu, X.; Wang, S.; Gao, P.; et al. Hypoxanthine Induces Muscular ATP Depletion and Fatigue via UCP2. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 647743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudzinska, W.; Lubkowska, A. Changes in the Concentration of Purine and Pyridine as a Response to Single Whole-Body Cryostimulation. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 634816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hering, C.; Conover, G.M. Advancing Ischemic Stroke Prognosis: Key Role of MiR-155 Non-Coding RNA. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lei, Z.; Sun, T. The role of microRNAs in neurodegenerative diseases: A review. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2023, 39, 53–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Y.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Han, B. Correlation analysis of miRNA-124, miRNA-210 with brain injury and inflammatory response in patients with craniocerebral injury. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2022, 14, 285–294. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.; Deng, S.; Li, Y.; Qu, S.; Liu, C.; Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Liu, T.; Li, Y. Synergistic Neuroprotection of Artesunate and Tetramethylpyrazine in Ischemic Stroke, Mechanisms of Blood–Brain Barrier Preservation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakkar, P.; Almusined, M.; Kakkar, T.; Munyombwe, T.; Makawa, L.; Kain, K.; Hassan, A.; Saha, S. Circulating Blood-Brain Barrier Proteins for Differentiating Ischaemic Stroke Patients from Stroke Mimics. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Dumitru, A.V.; Eva, L.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Ciurea, A.V. Nanoparticle Strategies for Treating CNS Disorders: A Comprehensive Review of Drug Delivery and Theranostic Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhao, W. Bidirectional Role of Pericytes in Ischemic Stroke. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, J.; Tsao, C.-C.; Patkar, S.; Huang, S.-F.; Francia, S.; Magnussen, S.N.; Gassmann, M.; Vogel, J.; Köster-Hegmann, C.; Ogunshola, O.O. Pericyte, but not astrocyte, hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) drives hypoxia-induced vascular permeability in vivo. Fluids Barriers CNS 2022, 19, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén-Yunta, M.; Valcárcel-Hernández, V.; García-Aldea, Á.; Soria, G.; García-Verdugo, J.M.; Montero-Pedrazuela, A.; Guadaño-Ferraz, A. Neurovascular unit disruption and blood–brain barrier leakage in MCT8 deficiency. Fluids Barriers CNS 2023, 20, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Wu, M.; Huang, Y.; He, X.; Yuan, J.; Dang, B. Research developments in the neurovascular unit and the blood-brain barrier (Review). Biomed. Rep. 2025, 22, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.; Bayat, A.-H.; Pearse, D.D. Small Extracellular Vesicles in Neurodegenerative Disease: Emerging Roles in Pathogenesis, Biomarker Discovery, and Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnatz, A.; Müller, C.; Brahmer, A.; Krämer-Albers, E. Extracellular Vesicles in neural cell interaction and CNS homeostasis. FASEB Bioadv. 2021, 3, 577–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Mei, Q.; Hou, X.; Manaenko, A.; Zhou, L.; Liebeskind, D.S.; Zhang, J.H.; Li, Y.; Hu, Q. Imaging Acute Stroke: From One-Size-Fit-All to Biomarkers. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 697779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGroat, W.; Abdelhalim, H.; Peker, E.; Sheth, N.; Narayanan, R.; Zeeshan, S.; Liang, B.T.; Ahmed, Z. Multimodal AI/ML for discovering novel biomarkers and predicting disease using multi-omics profiles of patients with cardiovascular diseases. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26503, Erratum in Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayanan, R.; Peker, E.; DeGroat, W.; Mendhe, D.; Zeeshan, S.; Ahmed, Z. 3D IntelliGenes: AI/ML application using multi-omics data for biomarker discovery and disease prediction with multi-dimensional visualization. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2025, 25, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shehjar, F.; Maktabi, B.; Rahman, Z.; Bahader, G.; Antonisamy, W.J.; Naqvi, A.; Mahajan, R.; Shah, Z.A. Stroke: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapies: Update on Recent Developments. Neurochem. Int. 2023, 162, 105458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, W.J.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.K. Monitoring Acute Stroke Progression: Multi-Parametric OCT Imaging of Cortical Perfusion, Flow, and Tissue Scattering in a Mouse Model of Permanent Focal Ischemia. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2019, 38, 1427–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maida, C.D.; Norrito, R.L.; Rizzica, S.; Mazzola, M.; Scarantino, E.R.; Tuttolomondo, A. Molecular Pathogenesis of Ischemic and Hemorrhagic Strokes: Background and Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, M.; Fang, Z.; Wang, H. Immunological Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies in Cerebral Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury: From Inflammatory Response to Neurorepair. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurcau, A.; Simion, A. Neuroinflammation in Cerebral Ischemia and Ischemia/Reperfusion Injuries: From Pathophysiology to Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, F.; Wang, R.; Yi, Z.; Luo, P.; Liu, W.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, Q. Tissue macrophages: Origin, heterogenity, biological functions, diseases and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirarchi, A.; Albi, E.; Arcuri, C. Microglia Signatures: A Cause or Consequence of Microglia-Related Brain Disorders? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maziz, M.N.H.; Chakravarthi, S.; Aung, T.; Htoo, P.M.; Shwe, W.H.; Gupalo, S.; Udayah, M.W.; Singh, H.; Kabir, M.S.; Thangarajan, R.; et al. Microglia-Mediated Neuroinflammation Through Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Signaling Causes Cognitive Dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, R. NLRP3 inflammasome in neuroinflammation and central nervous system diseases. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2025, 22, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, J.L.; Nissen, J.C. The Pathological Activation of Microglia Is Modulated by Sexually Dimorphic Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flower, L.; Vozza, E.G.; Bryant, C.E.; Summers, C. Role of inflammasomes in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Thorax 2025, 80, e222596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Chai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X. Astrocyte-mediated inflammatory responses in traumatic brain injury: Mechanisms and potential interventions. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1584577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shen, G.; Zhou, X.; Li, J. Therapeutic potential of tumor-associated neutrophils: Dual role and phenotypic plasticity. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, Y.R.; Huang, M.; Chang, J.Y.; Sim, A.Y.; Jung, H.; Lee, W.T.; Hyun, Y.-M.; Lee, J.E. Reparative System Arising from CCR2(+) Monocyte Conversion Attenuates Neuroinflammation Following Ischemic Stroke. Transl. Stroke Res. 2021, 12, 879–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghdoust, M.; Das, A.; Kaushik, D.K. Fueling neurodegeneration: Metabolic insights into microglia functions. J. Neuroinflamm. 2024, 21, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banoei, M.M.; Hashemi Shahraki, A.; Santos, K.; Holt, G.; Mirsaeidi, M. Metabolomics and Cytokine Signatures in COVID-19: Uncovering Immunometabolism in Pathogenesis. Metabolites 2025, 15, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machoń, N.J.; Zdanowska, N.; Klimek-Trojan, P.; Owczarczyk-Saczonek, A. Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 and E-Selectin as Potential Cardiovascular Risk Biomarkers in Psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, A.; Theus, M.H. Mechanisms of Blood–Brain Barrier Dysfunction in Traumatic Brain Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Wang, J.; Lin, Z.; Shi, G.; Wang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, J. MMP-9 as a Biomarker for Predicting Hemorrhagic Strokes in Moyamoya Disease. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 721118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Niu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xia, C.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Feng, H. Meningeal lymphatic drainage: Novel insights into central nervous system disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, S.; Pulli, B.; Heit, J.J. Neuroinflammation and acute ischemic stroke: Impact on translational research and clinical care. Front. Surg. 2025, 12, 1501359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, K.G.; Dodd, G.K.; Alhamdi, S.; Asimenios, P.G.; Dagda, R.K.; De Meirleir, K.L.; Hudig, D.; Lombardi, V.C. Mucosal Immunity and the Gut-Microbiota-Brain-Axis in Neuroimmune Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayarri-Olmos, R.; Bain, W.; Iwasaki, A. The role of complement in long COVID pathogenesis. JCI Insight 2025, 10, e194314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starikova, E.A.; Mammedova, J.T.; Rubinstein, A.A.; Sokolov, A.V.; Kudryavtsev, I.V. Activation of the Coagulation Cascade as a Universal Danger Sign. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorite, P.; Domínguez, J.N.; Palomeque, T.; Torres, M.I. Extracellular Vesicles: Advanced Tools for Disease Diagnosis, Monitoring, and Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sternby, H.; Hartman, H.; Thorlacius, H.; Regnér, S. The Initial Course of IL1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IFN-γ and TNF-α with Regard to Severity Grade in Acute Pancreatitis. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães de Almeida Barros, A.; Roquim e Silva, L.; Pessoa, A.; Eiras Falcão, A.; Viana Magno, L.A.; Valadão Freitas Rosa, D.; Aurelio Romano Silva, M.; Marques de Miranda, D.; Nicolato, R. Use of biomarkers for predicting a malignant course in acute ischemic stroke: An observational case–control study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinicke, M.; Shamkeeva, S.; Hell, M.; Isermann, B.; Ceglarek, U.; Heinemann, M.L. Targeted Lipidomics for Characterization of PUFAs and Eicosanoids in Extracellular Vesicles. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ene, J.; Liu, C.; Syed, F.; Sun, L.; Berry, D.; Durairaj, P.; Liu, Z.L.; Zeng, C.; Jung, S.; Li, Y. Biomanufacturing and lipidomics analysis of extracellular vesicles secreted by human blood vessel organoids in a vertical wheel bioreactor. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamas, S.; Rahil, R.R.; Kaushal, L.; Sharma, V.K.; Wani, N.A.; Qureshi, S.H.; Ahmad, S.F.; Attia, S.M.; Zargar, M.A.; Hamid, A.; et al. Pyroptosis in Endothelial Cells and Extracellular Vesicle Release in Atherosclerosis via NF-κB-Caspase-4/5-GSDM-D Pathway. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corica, F.; De Feo, M.S.; Gorica, J.; Sidrak, M.M.A.; Conte, M.; Filippi, L.; Schillaci, O.; De Vincentis, G.; Frantellizzi, V. PET Imaging of Neuro-Inflammation with Tracers Targeting the Translocator Protein (TSPO), a Systematic Review: From Bench to Bedside. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, F.; Chen, Q.; Luo, X.; Xie, S.; Wei, Y.; Li, X.; Li, K.; Lebeau, B.; Ling, C.; Dao, F.; et al. A Multi-Omics Integration Framework with Automated Machine Learning Identifies Peripheral Immune-Coagulation Biomarkers for Schizophrenia Risk Stratification. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, B.; Yang, W.; Ma, F.; Zou, J.; Li, K.; Tan, S.; Feng, J.; Wang, Y.; Qin, Z.; et al. Longitudinal plasma proteome profiling reveals the diversity of biomarkers for diagnosis and cetuximab therapy response of colorectal cancer. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Rodriguez, N.; Garcia-Gabilondo, M.; Rodriguez, S.; Tejada, P.I.; Miranda-Artieda, Z.M.; Ridao, N.; Buxó, X.; Pérez-Mesquida, M.E.; Beseler, M.R.; Salom, J.B.; et al. Identifying new blood biomarkers of neuroplasticity associated with rehabilitation outcomes after stroke. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 38047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Z.; Guo, J.; Liu, B.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, C.; Jiang, Y.; Liang, N.; Hu, M.; Song, T.; Yang, L.; et al. Mechanisms of immune response and cell death in ischemic stroke and their regulation by natural compounds. Front. Immunol. 2024, 14, 1287857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerban, M.; Toader, C.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A. Blueprint of Collapse: Precision Biomarkers, Molecular Cascades, and the Engineered Decline of Fast-Progressing ALS. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo-Castro, S.; Albino, I.; Barrera-Sandoval, Á.M.; Tomatis, F.; Sousa, J.A.; Martins, E.; Simões, S.; Lino, M.M.; Ferreira, L.; Sargento-Freitas, J. Therapeutic Nanoparticles for the Different Phases of Ischemic Stroke. Life 2021, 11, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerban, M.; Toader, C.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A. CRISPR and Artificial Intelligence in Neuroregeneration: Closed-Loop Strategies for Precision Medicine, Spinal Cord Repair, and Adaptive Neuro-Oncology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierke, C.T. Bidirectional Mechanical Response Between Cells and Their Microenvironment. Front. Phys. 2021, 9, 749830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Rout, S.; Deep, P.; Sahu, C.; Samal, P.K. The Dual Role of Astrocytes in CNS Homeostasis and Dysfunction. Neuroglia 2025, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Su, G.; Chai, M.; An, Y.; Song, J.; Zhang, Z. Astrogliosis and glial scar in ischemic stroke—Focused on mechanism and treatment. Exp. Neurol. 2025, 385, 115131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, F.; Cui, J.; Wang, P.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Li, L. The Phenotype Changes of Astrocyte During Different Ischemia Conditions. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huss, A.; Abdelhak, A.; Mayer, B.; Tumani, H.; Müller, H.-P.; Althaus, K.; Kassubek, J.; Otto, M.; Ludolph, A.C.; Yilmazer-Hanke, D.; et al. Association of Serum GFAP with Functional and Neurocognitive Outcome in Sporadic Small Vessel Disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz de León-López, C.A.; Navarro-Lobato, I.; Khan, Z.U. The Role of Astrocytes in Synaptic Dysfunction and Memory Deficits in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.-C.; Ho, S.-Y.; Tsai, C.-W.; Chen, E.-L.; Liou, H.-H. Microglia-Impaired Phagocytosis Contributes to the Epileptogenesis in a Mouse Model of Dravet Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, C.; Liu, Z.; Qie, S. The Implications of Microglial Regulation in Neuroplasticity-Dependent Stroke Recovery. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Pan, L.; Sun, C.; Ma, C.; Pan, H. Balancing Microglial Density and Activation in Central Nervous System Development and Disease. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pajevic, S.; Plenz, D.; Basser, P.J.; Fields, R.D. Oligodendrocyte-mediated myelin plasticity and its role in neural synchronization. eLife 2023, 12, e81982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballato, M.; Germanà, E.; Ricciardi, G.; Giordano, W.G.; Tralongo, P.; Buccarelli, M.; Castellani, G.; Ricci-Vitiani, L.; D’Alessandris, Q.G.; Giuffrè, G.; et al. Understanding Neovascularization in Glioblastoma: Insights from the Current Literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Kim, M.-J.; Kumar, A.; Lee, H.-W.; Yang, Y.; Kim, Y. Vascular endothelial growth factor signaling in health and disease: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic perspectives. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waszczykowska, A.; Podgórski, M.; Waszczykowski, M.; Gerlicz- Kowalczuk, Z.; Jurowski, P. Matrix Metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9, Their Inhibitors TIMP-1 and TIMP-2, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and sVEGFR-2 as Predictive Markers of Ischemic Retinopathy in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis—Case Series Report. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Fan, B.; Chopp, M.; Zhang, Z. Epigenetic Mechanisms Underlying Adult Post Stroke Neurogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-C.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.-A.; Young, T.-H.; Wu, C.-C.; Chiang, Y.-H.; Kao, C.-H.; Huang, A.P.-H.; Hsu, Y.-H.; Chen, K.-Y.; et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor contributes to neurogenesis after intracerebral hemorrhage: A rodent model and human study. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1170251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Huo, X.; Shen, L.; Qian, M.; Wang, J.; Mao, S.; Chen, W.; Li, R.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, B.; et al. Astrocyte heterogeneity in ischemic stroke: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Neurobiol. Dis. 2025, 209, 106885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.-Y.; Gao, Y.-M.; Feng, T.; Rao, J.-S.; Zhao, C. Enhancing Functional Recovery After Spinal Cord Injury Through Neuroplasticity: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poitras, T.; Zochodne, D.W. Unleashing Intrinsic Growth Pathways in Regenerating Peripheral Neurons. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Yi, R.; Zhong, F.; Lu, Y.; Chen, W.; Ke, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Wang, P.; Li, W. Oligodendrocytes and myelination: Pioneering new frontiers in cognitive neuroscience. Front. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1618468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukkieva, T.; Pospelova, M.; Efimtsev, A.; Fionik, O.; Alekseeva, T.; Samochernych, K.; Gorbunova, E.; Krasnikova, V.; Makhanova, A.; Levchuk, A.; et al. Functional Network Connectivity Reveals the Brain Functional Alterations in Breast Cancer Survivors. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anichini, A.; Caruso, F.P.; Lagano, V.; Noviello, T.M.R.; Tufano, R.; Nicolini, G.; Molla, A.; Bersani, I.; Sgambelluri, F.; Covre, A.; et al. Integrated multi-omics profiling reveals the role of the DNA methylation landscape in shaping biological heterogeneity and clinical behaviour of metastatic melanoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, T.; Wang, L.; Feng, C.; Xu, J.; Shao, B.; Cheng, B.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y. ECM remodeling by PDGFRβ+ dental pulp stem cells drives angiogenesis and pulp regeneration via integrin signaling. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo-Muelas, A.; Morante-Redolat, J.M.; Moncho-Amor, V.; Jordán-Pla, A.; Pérez-Villalba, A.; Carrillo-Barberà, P.; Belenguer, G.; Porlan, E.; Kirstein, M.; Bachs, O.; et al. The rates of adult neurogenesis and oligodendrogenesis are linked to cell cycle regulation through p27-dependent gene repression of SOX2. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2023, 80, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Gangadaran, P.; Dhara, C.; Ghosh, S.; Phadikar, S.D.; Chakraborty, A.; Mahajan, A.A.; Mondal, R.; Chattopadhyay, D.; Banerjee, T.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles in Osteogenesis: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential for Bone Regeneration. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidorov, E.V.; Xu, C.; Garcia-Ramiu, J.; Blair, A.; Ortiz-Garcia, J.; Gordon, D.; Chainakul, J.; Sanghera, D.K. Global Metabolomic Profiling Reveals Disrupted Lipid and Amino Acid Metabolism Between the Acute and Chronic Stages of Ischemic Stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2022, 31, 106320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokkinos, V.; Chatzisotiriou, A.; Seimenis, I. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Diffusion Tensor Imaging-Tractography in Resective Brain Surgery: Lesion Coverage Strategies and Patient Outcomes. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Cai, Q.; Chen, K.; Kahler, B.; Yao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, D.; Lu, Y. Machine learning models for prognosis prediction in regenerative endodontic procedures. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lai, D.; Li, R.; Chen, H.; Huang, X.; Ning, J. A Biomarker Signature-Guided Clinical Trial Design for Precision Medicine. Stat. Med. 2025, 44, e70103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wlodarczyk, L.; Szelenberger, R.; Cichon, N.; Saluk-Bijak, J.; Bijak, M.; Miller, E. Biomarkers of Angiogenesis and Neuroplasticity as Promising Clinical Tools for Stroke Recovery Evaluation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerban, M.; Toader, C.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A. Brain Tumors, AI and Psychiatry: Predicting Tumor-Associated Psychiatric Syndromes with Machine Learning and Biomarkers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.-X.; Li, C.-R.; Lu, Z.-J.; Kong, N.; Huang, R.-H.; Ma, S.-Y.; Zhou, W.-F.; Jiao, H.; Qiu, Y.; Yu, Y.-F.; et al. Remodeling and repair of the damaged brain: The potential and challenges of organoids for ischaemic stroke. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voicu, V.; Toader, C.; Șerban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Ciurea, A.V. Systemic Neurodegeneration and Brain Aging: Multi-Omics Disintegration, Proteostatic Collapse, and Network Failure Across the CNS. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissoneault, C.; Rose, D.K.; Grimes, T.; Waters, M.F.; Khanna, A.; Datta, S.; Daly, J.J. Trajectories of stroke recovery of impairment, function, and quality of life in response to 12-month mobility and fitness intervention. NeuroRehabilitation 2021, 49, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzola, P.; Melzer, T.; Pavesi, E.; Gil-Mohapel, J.; Brocardo, P.S. Exploring the Role of Neuroplasticity in Development, Aging, and Neurodegeneration. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagrebelsky, M.; Tacke, C.; Korte, M. BDNF signaling during the lifetime of dendritic spines. Cell Tissue Res. 2020, 382, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanhueza, M.; Lisman, J. The CaMKII/NMDAR complex as a molecular memory. Mol. Brain 2013, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küspert, M.; Hammer, A.; Bösl, M.R.; Wegner, M. Olig2 regulates Sox10 expression in oligodendrocyte precursors through an evolutionary conserved distal enhancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 1280–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yim, M.M.; Jin, Y.X.; Tao, B.K.; Xie, J.S.; Balas, M.; Khan, H.; Lam, W.-C.; Yan, P.; Navajas, E.V. Circulating Cell-Free DNA as an Epigenetic Biomarker for Early Diabetic Retinopathy: A Narrative Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawal, O.; Ulloa Severino, F.P.; Eroglu, C. The role of astrocyte structural plasticity in regulating neural circuit function and behavior. Glia 2022, 70, 1467–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Sheng, Z.-H.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Z.-B.; Xue, R.-J.; Tan, L.; Tan, M.-S.; Wang, Z.-T. Complement C1q is associated with neuroinflammation and mediates the association between amyloid-β and tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Transl. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; Qi, X.; Cai, Q.; Niu, L.; Huang, X.; Zhang, D.; Ling, J.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, P.; et al. The role of NLRP3 inflammasome in aging and age-related diseases. Immun. Ageing 2024, 21, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zedde, M.; Grisendi, I.; Assenza, F.; Napoli, M.; Moratti, C.; Di Cecco, G.; D’Aniello, S.; Valzania, F.; Pascarella, R. Stroke-Induced Secondary Neurodegeneration of the Corticospinal Tract—Time Course and Mechanisms Underlying Signal Changes in Conventional and Advanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnello, L.; Gambino, C.M.; Ciaccio, A.M.; Cacciabaudo, F.; Massa, D.; Masucci, A.; Tamburello, M.; Vassallo, R.; Midiri, M.; Scazzone, C.; et al. From Amyloid to Synaptic Dysfunction: Biomarker-Driven Insights into Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.H. The Impact of Walking on BDNF as a Biomarker of Neuroplasticity: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.T.; Hicks, S.D.; Bergquist, B.K.; Maloney, K.A.; Dennis, V.E.; Bammel, A.C. Preliminary Evidence for Neuronal Dysfunction Following Adverse Childhood Experiences: An Investigation of Salivary MicroRNA Within a High-Risk Youth Sample. Genes 2024, 15, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limketkai, B.N.; Maas, L.; Krishna, M.; Dua, A.; DeDecker, L.; Sauk, J.S.; Parian, A.M. Machine Learning-based Characterization of Longitudinal Health Care Utilization Among Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2024, 30, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermawan, D.; Alotaiq, N. From Lab to Clinic: How Artificial Intelligence (AI) Is Reshaping Drug Discovery Timelines and Industry Outcomes. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzón-Fernández, M.V.; Saavedra-Torres, J.S.; López Garzón, N.A.; Pachon-Bueno, J.S.; Tamayo-Giraldo, F.J.; Rojas Gomez, M.C.; Arias-Intriago, M.; Gaibor-Pazmiño, A.; López-Cortés, A.; Izquierdo-Condoy, J.S. NLRP3 and beyond: Inflammasomes as central cellular hub and emerging therapeutic target in inflammation and disease. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1624770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gipson, C.D.; Olive, M.F. Structural and functional plasticity of dendritic spines—Root or result of behavior? Genes Brain Behav. 2017, 16, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Xu, W.; Ma, R.; Lee, J.-W.; Dela Peña, T.A.; Yang, W.; Li, B.; Li, M.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Isomerized Green Solid Additive Engineering for Thermally Stable and Eco-Friendly All-Polymer Solar Cells with Approaching 19% Efficiency. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2308334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, Y.H.I.; Shamkh, I.M.; Alharthi, N.S.; Shanawaz, M.A.; Alzahrani, H.A.; Jabbar, B.; Beigh, S.; Alghamdi, S.; Alsakhen, N.; Khidir, E.B.; et al. Discovery of 1-(5-bromopyrazin-2-yl)-1-[3-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl]urea as a promising anticancer drug via synthesis, characterization, biological screening, and computational studies. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadi, H.R.; Mirakbari, S.M.; Allami, A.; Salavati, E. Factors Determining Primary Coronary Slow Flow Phenomenon among Opium Users and Non-users: A Case Control Study in Northern Iran. Addict. Health 2022, 14, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.C.R.; Jahr, F.M.; Hawkins, E.; Kronfol, M.M.; Younis, R.M.; McClay, J.L.; Deshpande, L.S. Epigenetic histone acetylation and Bdnf dysregulation in the hippocampus of rats exposed to repeated, low-dose diisopropylfluorophosphate. Life Sci. 2021, 281, 119765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodler, S.; Bujoreanu, C.E.; Baekelandt, L.; Volpi, G.; Puliatti, S.; Kowalewski, K.-F.; Belenchon, I.R.; Taratkin, M.; Rivas, J.G.; Veccia, A.; et al. The Impact on Urology Residents’ Learning of Social Media and Web Technologies after the Pandemic: A Step Forward through the Sharing of Knowledge. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotoh, M.; Miyamoto, Y.; Ikeshima-Kataoka, H. Astrocytic Neuroimmunological Roles Interacting with Microglial Cells in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.; Zaghi, A.; Rankin, S. Marginalising dyslexic researchers is bad for science. eLife 2023, 12, e93980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Lee, G.-S. Potential Role of Inflammasomes in Aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhunchha, B.; Kubo, E.; Lehri, D.; Singh, D.P. NLRP3 Inflammasome and Inflammatory Response in Aging Disorders: The Entanglement of Redox Modulation in Different Outcomes. Cells 2025, 14, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, A.M.; Merluzzi, A.P.; Adluru, N.; Norton, D.; Koscik, R.L.; Clark, L.R.; Berman, S.E.; Nicholas, C.R.; Asthana, S.; Alexander, A.L.; et al. Association of longitudinal white matter degeneration and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of neurodegeneration, inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease in late-middle-aged adults. Brain Imaging Behav. 2019, 13, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, P.; Pedrini, S.; Doecke, J.D.; Thota, R.; Villemagne, V.L.; Doré, V.; Singh, A.K.; Wang, P.; Rainey-Smith, S.; Fowler, C.; et al. Plasma Aβ42/40 ratio, p-tau181, GFAP, and NfL across the Alzheimer’s disease continuum: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study in the AIBL cohort. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, 1117–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Wang, C.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Multi-omics approaches for biomarker discovery and precision diagnosis of prediabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1520436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenchov, R.; Sasso, J.M.; Zhou, Q.A. Alzheimer’s Disease: Exploring the Landscape of Cognitive Decline. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2024, 15, 3800–3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balch, M.H.H.; Nimjee, S.M.; Rink, C.; Hannawi, Y. Beyond the Brain: The Systemic Pathophysiological Response to Acute Ischemic Stroke. J. Stroke 2020, 22, 159–172, Erratum in J. Stroke 2020, 22, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furrer, R.; Handschin, C. Biomarkers of aging: From molecules and surrogates to physiology and function. Physiol. Rev. 2025, 105, 1609–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, M.-J.; Liou, D.-Y.; Fay, L.-Y.; Huang, S.-L.; Huang, W.-C.; Chern, C.-M.; Tsai, S.-K.; Cheng, H.; Huang, S.-S. Targeting the Ischemic Core: A Therapeutic Microdialytic Approach to Prevent Neuronal Death and Restore Functional Behaviors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, M.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, W.; Ge, J.; Mei, Z. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Central Nervous System Diseases: Advancing Translational Neuropathology via Single-Cell and Spatial Multiomics. MedComm 2025, 6, e70328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Préau, L.; Lischke, A.; Merkel, M.; Oegel, N.; Weissenbruch, M.; Michael, A.; Park, H.; Gradl, D.; Kupatt, C.; le Noble, F. Parenchymal cues define Vegfa-driven venous angiogenesis by activating a sprouting competent venous endothelial subtype. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Song, C.; Shi, J.; Wei, Z.; Wang, J.; Huang, W.; Zhang, R.; Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, G.; et al. Endothelium-specific endoglin triggers astrocyte reactivity via extracellular vesicles in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2025, 20, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iordache, M.P.; Buliman, A.; Costea-Firan, C.; Gligore, T.C.I.; Cazacu, I.S.; Stoian, M.; Teoibaș-Şerban, D.; Blendea, C.-D.; Protosevici, M.G.-I.; Tanase, C.; et al. Immunological and Inflammatory Biomarkers in the Prognosis, Prevention, and Treatment of Ischemic Stroke: A Review of a Decade of Advancement. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Cui, Y.; Li, J.; Li, P.; Huang, X. Integrated microfluidic platforms for extracellular vesicles: Separation, detection, and clinical translation. APL Bioeng. 2025, 9, 031502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatami-Fard, G.; Anastasova-Ivanova, S. Advancements in Cerebrospinal Fluid Biosensors: Bridging the Gap from Early Diagnosis to the Detection of Rare Diseases. Sensors 2024, 24, 3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaka, Y.; Yashiro, R. Molecular Regulation and Therapeutic Applications of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor–Tropomyosin-Related Kinase B Signaling in Major Depressive Disorder Though Its Interaction with Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and N-Methyl-D-Aspartic Acid Receptors: A Narrative Review. Biologics 2025, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, D.M.; Peruzzotti-Jametti, L.; Giebel, B.; Pluchino, S. Extracellular vesicles set the stage for brain plasticity and recovery by multimodal signalling. Brain 2023, 147, 372–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowluru, R.A.; Kumar, J. Mitochondrial Fragmentation and Long Noncoding RNA MALAT1 in Diabetic Retinopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerban, M.; Toader, C.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A. The Collapse of Brain Clearance: Glymphatic-Venous Failure, Aquaporin-4 Breakdown, and AI-Empowered Precision Neurotherapeutics in Intracranial Hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murcko, R.; Marchi, N.; Bailey, D.; Janigro, D. Diagnostic biomarker kinetics: How brain-derived biomarkers distribute through the human body, and how this affects their diagnostic significance: The case of S100B. Fluids Barriers CNS 2022, 19, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Ning, B. Reactive Astrocytes in Central Nervous System Injury: Subgroup and Potential Therapy. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 792764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, K.A.; Gloger, E.M.; Pinheiro, C.N.; Schmitt, F.A.; Segerstrom, S.C. Associations between IL-1β, IL-6, and TNFα polymorphisms and longitudinal trajectories of cognitive function in non-demented older adults. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2024, 39, 100816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Wang, Y.; Wei, R.; Li, C.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, T.; Zhang, H.; Lin, L.; Xu, B. Peripheral Blood Th1/Th17 Immune Cell Shift is Associated with Disease Activity and Severity of AQP4 Antibody Sero-Positive Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2023, 19, 2413–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpe, C.; Monaco, L.; Relucenti, M.; Iovino, L.; Familiari, P.; Scavizzi, F.; Raspa, M.; Familiari, G.; Civiero, L.; D’Agnano, I.; et al. Microglia-Derived Small Extracellular Vesicles Reduce Glioma Growth by Modifying Tumor Cell Metabolism and Enhancing Glutamate Clearance through miR-124. Cells 2021, 10, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Jin, H.; Yulug, B.; Altay, O.; Li, X.; Hanoglu, L.; Cankaya, S.; Coskun, E.; Idil, E.; Nogaylar, R.; et al. Multi-omics analysis reveals the key factors involved in the severity of the Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2024, 16, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullell, N.; Caruana, G.; Elias-Mas, A.; Delgado-Sanchez, A.; Artero, C.; Buongiorno, M.T.; Almería, M.; Ray, N.J.; Correa, S.A.L.; Krupinski, J. Glymphatic system clearance and Alzheimer’s disease risk: A CSF proteome-wide study. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2025, 17, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, F.; Saloner, R.; Vogel, J.W.; Krish, V.; Abdel-Azim, G.; Ali, M.; An, L.; Anastasi, F.; Bennett, D.; Pichet Binette, A.; et al. The Global Neurodegeneration Proteomics Consortium: Biomarker and drug target discovery for common neurodegenerative diseases and aging. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 2556–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oblitas, C.-M.; Sampedro-Viana, A.; Fernández-Rodicio, S.; Rodríguez-Yáñez, M.; López-Dequidt, I.; Gonzalez-Quintela, A.; Mosqueira, A.J.; Porto-Álvarez, J.; Martínez Fernández, J.; González-Simón, I.; et al. Molecular and Neuroimaging Profile Associated with the Recurrence of Different Types of Strokes: Contribution from Real-World Data. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Bonilla, L.; Shahanoor, Z.; Sciortino, R.; Nazarzoda, O.; Racchumi, G.; Iadecola, C.; Anrather, J. Analysis of brain and blood single-cell transcriptomics in acute and subacute phases after experimental stroke. Nat. Immunol. 2024, 25, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez Reyes, C.D.; Alejo-Jacuinde, G.; Perez Sanchez, B.; Chavez Reyes, J.; Onigbinde, S.; Mogut, D.; Hernández-Jasso, I.; Calderón-Vallejo, D.; Quintanar, J.L.; Mechref, Y. Multi Omics Applications in Biological Systems. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 5777–5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.; Uyeda, A.; Manabe, I.; Muramatsu, R. Astrocytic heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U is involved in scar formation after spinal cord injury. J. Neuroinflamm. 2025, 22, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoryan, E.; Markitantova, Y. Epigenetic Modifications in the Retinal Pigment Epithelium of the Eye During RPE-Related Regeneration or Retinal Diseases in Vertebrates. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuppe, C.; Ramirez Flores, R.O.; Li, Z.; Hayat, S.; Levinson, R.T.; Liao, X.; Hannani, M.T.; Tanevski, J.; Wünnemann, F.; Nagai, J.S.; et al. Spatial multi-omic map of human myocardial infarction. Nature 2022, 608, 766–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Glass, C.K. Microglia networks within the tapestry of alzheimer’s disease through spatial transcriptomics. Mol. Neurodegener. 2025, 20, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syafrizayanti; Lueong, S.S.; Di, C.; Schaefer, J.V.; Plückthun, A.; Hoheisel, J.D. Personalised proteome analysis by means of protein microarrays made from individual patient samples. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 39756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.Y.; Yeung, P.S.W.; Mann, M.W.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Y.K.; Hoofnagle, A.N. Post-Translationally Modified Proteoforms as Biomarkers: From Discovery to Clinical Use. Clin. Chem. 2025, 71, 1111–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, R.-T.T.; Ko, J. Future of Digital Assays to Resolve Clinical Heterogeneity of Single Extracellular Vesicles. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 11619–11645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, H.L.; Zheng, W.; Issadore, D.A.; Im, H.; Cho, Y.-K.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; Liu, Y.; Li, B.; Liu, F.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles for Clinical Diagnostics: From Bulk Measurements to Single-Vesicle Analysis. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 28021–28109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xiao, D.; Mao, Q.; Xia, H. Role of neuroinflammation in neurodegeneration development. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohara, M.; Hattori, T. The Glymphatic System in Cerebrospinal Fluid Dynamics: Clinical Implications, Its Evaluation, and Application to Therapeutics. Neurodegener. Dis. 2025, 25, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wysoczański, B.; Świątek, M.; Wójcik-Gładysz, A. Organ-on-a-Chip Models—New Possibilities in Experimental Science and Disease Modeling. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Sinha, S.; Aldape, K.; Hannenhalli, S.; Sahinalp, C.; Ruppin, E. Big data in basic and translational cancer research. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinwumi, P.O.; Ojo, S.; Nathaniel, T.I.; Wanliss, J.; Karunwi, O.; Sulaiman, M. Evaluating machine learning models for stroke prediction based on clinical variables. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1668420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norelyaqine, A.; Azmi, R.; Saadane, A. Architecture of Deep Convolutional Encoder-Decoder Networks for Building Footprint Semantic Segmentation. Sci. Program. 2023, 2023, 8552624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onciul, R.; Tataru, C.-I.; Dumitru, A.V.; Crivoi, C.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Radoi, M.P.; Toader, C. Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience: Transformative Synergies in Brain Research and Clinical Applications. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, P.L.; Vaigeshwari, V.; Mohammed Reyasudin, B.K.; Noor Hidayah, B.R.A.; Tatchanaamoorti, P.; Yeow, J.A.; Kong, F.Y. Integrating artificial intelligence in healthcare: Applications, challenges, and future directions. Future Sci. OA 2025, 11, 2527505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, J.L.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Shen, L.; Long, Q. Deep learning-based approaches for multi-omics data integration and analysis. BioData Min. 2024, 17, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, R.; Zecca, C.; Chimienti, G.; Latronico, T.; Liuzzi, G.M.; Pesce, V.; Dell’Abate, M.T.; Borlizzi, F.; Giugno, A.; Urso, D.; et al. Reliable New Biomarkers of Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress and Neuroinflammation in Cerebrospinal Fluid and Plasma from Alzheimer’s Disease Patients: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Tataru, C.P.; Munteanu, O.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Ciurea, A.V.; Enyedi, M. Decoding Neurodegeneration: A Review of Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Advances in Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and ALS. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, C.; Bhattacharya, M.; Pal, S.; Lee, S.-S. From machine learning to deep learning: Advances of the recent data-driven paradigm shift in medicine and healthcare. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 2024, 7, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, P.; Hormel, T.T.; Wang, J.; Guo, Y.; Bailey, S.T.; Flaxel, C.J.; Huang, D.; Hwang, T.S.; Jia, Y. Interpretable Diabetic Retinopathy Diagnosis based on Biomarker Activation Map. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 71, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariam, Z.; Niazi, S.K.; Magoola, M. Unlocking the Future of Drug Development: Generative AI, Digital Twins, and Beyond. BioMedInformatics 2024, 4, 1441–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvino, G.; Peconi, C.; Strafella, C.; Trastulli, G.; Megalizzi, D.; Andreucci, S.; Cascella, R.; Caltagirone, C.; Zampatti, S.; Giardina, E. Federated Learning: Breaking Down Barriers in Global Genomic Research. Genes 2024, 15, 1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbani, S.A.; El-Tanani, M.; Sharma, S.; Rabbani, S.S.; El-Tanani, Y.; Kumar, R.; Saini, M. Generative Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Applications, Implementation Challenges, and Future Directions. BioMedInformatics 2025, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondaveeti, H.K.; Simhadri, C.G. Evaluation of deep learning models using explainable AI with qualitative and quantitative analysis for rice leaf disease detection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Q.; Zhao, T.; Liu, M.; Cao, D.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Xia, M.; Wang, X.; Zheng, T.; Liu, C.; et al. Targeting NLRP3 Inflammasome in Translational Treatment of Nervous System Diseases: An Update. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 707696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Park, C.; Shahbazi, M.; York, M.K.; Kunik, M.E.; Naik, A.D.; Najafi, B. Digital Biomarkers of Cognitive Frailty: The Value of Detailed Gait Assessment Beyond Gait Speed. Gerontology 2022, 68, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rust, R.; Nih, L.R.; Liberale, L.; Yin, H.; El Amki, M.; Ong, L.K.; Zlokovic, B.V. Brain repair mechanisms after cell therapy for stroke. Brain 2024, 147, 3286–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Process | Mechanistic Events | Key Biomarkers | Time Window | Clinical Significance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic collapse and excitotoxicity | Rapid ATP depletion halts Na+/K+ and Ca2+ pumps → ionic imbalance and depolarization → massive glutamate release → NMDA/AMPA overactivation → Ca2+ overload, ROS generation, and mitochondrial permeability transition → cytochrome c release and caspase activation. | Lactate, succinate, glutamate, aspartate, NSE, UCH-L1, SBDPs, 8-OHdG, MDA, cytochrome c, caspase-3, and HIF-1α. | 0–2 h | Define ischemic-core formation. Succinate accumulation predicts ROS burst on reperfusion. NSE and UCH-L1 correlate with infarct size and outcomes. | [54,55] |

| Purine catabolism and stress response | ATP-breakdown products (hypoxanthine, and xanthine) rise; immune cells upregulate stress-responsive transcription factors and cytokine genes. | Hypoxanthine, xanthine, ATF3, NF-κB, and IL-6 mRNA. | 0.5–3 h | Reflect energy failure and systemic immune priming; correlate with stroke severity. | [56,57] |

| miRNA release | Neuronal and glial release of regulatory miRNAs modulate apoptosis, excitotoxicity, and inflammation. | miR-124, miR-9, miR-21, and miR-210. | 1–4 h | Predicts infarct expansion and early injury; enables rapid blood-based diagnosis. | [58,59,60] |

| BBB breakdown and endothelial activation | ROS, cytokines, and proteases (MMP-2/9) degrade tight junctions (claudin-5 and occludin); endothelial cells shed adhesion molecules; and thrombogenic activation ensues. | MMP-2, MMP-9, sICAM-1, sVCAM-1, sE-selectin, vWF, and TJ fragments. | 1–6 h | MMP-9 predicts infarct size and hemorrhagic transformation risk. Adhesion markers reflect endothelial activation and leukocyte recruitment. | [61,62,63] |

| Astrocyte and pericyte response | Astrocytes swell via AQP4 and release GFAP and S100B; pericytes detach, releasing PDGFR-β; and angiopoietins and ephrins alter perivascular signaling. | GFAP, S100B, PDGFR-β, Ang-1/2, and EphB ligands. | 2–6 h | GFAP differentiates ischemic vs. hemorrhagic stroke. PDGFR-β indicates microvascular destabilization. | [64,65] |

| Neurovascular unit leakage | BBB breach permits CNS molecules and exosomes into blood; and systemic cytokines and leukocytes exacerbate injury. | NfL, GFAP, and neuronal exosomes. | 2–6 h | Blood-based surrogates of CNS damage; useful for real-time monitoring of BBB integrity. | [66,67] |

| Extracellular vesicles | Neurons, glia, and endothelial cells release EVs with dynamic cargo reflecting cell stress and state. | EV-synaptophysin, EV-GFAP, miR-124, and miR-9. | 1–6 h | Offer minimally invasive biomarkers; support time-resolved profiling and personalized monitoring. | [68,69] |

| Imaging correlates | Perfusion MRI maps hypoperfusion and penumbra; DWI detects cytotoxic edema; and ADC and Tmax assess microvascular status. | ADC, Tmax, and perfusion maps. | Minutes–6 h | Complement molecular biomarkers; refine diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic targeting. | [70] |

| Composite biomarker panels and AI | Multi-omics and imaging data integrated by ML for real-time classification and prediction. | Composite panels and AI classifiers. | ≤6 h | Improve diagnostic precision, predict hemorrhagic risk; guide reperfusion and neuroprotective strategies. | [71,72] |

| Domain | Key Processes | Representative Biomarkers | Temporal Dynamics | Clinical/Translational Significance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural and network plasticity | Axonal sprouting, synaptic remodeling, dendritic spine turnover, and network reorganization. | GAP-43, SPRR1A, βIII-tubulin, BDNF, NGF, PSD-95, Homer, CREB, and CaMKII. | Weeks–months, peaking during rehabilitation and task engagement. | Indicators of neuroplastic potential and recovery trajectory; correlate with motor and cognitive gains; and guide intensity and timing of rehabilitation. | [159,160] |

| Myelin remodeling | Oligodendrocyte proliferation and differentiation, remyelination, and conduction restoration. | Olig2, Sox10, PDGF-AA, MBP, PLP, MOG, and oligodendrocyte-derived EVs. | Weeks–months, often delayed vs. synaptic changes. | Reflects white-matter repair and conduction recovery; predicts long-term connectivity and functional outcomes. | [161,162] |

| Epigenetic and transcriptomic remodeling | DNA methylation, histone acetylation, chromatin reorganization, and lncRNA/circRNA regulation. | Bdnf promoter methylation, H3K27ac, lncRNA MALAT1, circHIPK3, and miR-132. | Persistent, weeks–months, and dynamic with rehabilitation. | Mark latent plasticity potential; may stratify patients for epigenetic therapies or delayed rehab responsiveness. | [163,164] |

| Glial activation and maladaptive remodeling | Chronic astrocyte reactivity, inhibitory ECM formation, microglial activation, and complement overactivation. | GFAP, vimentin, CSPGs (neurocan and brevican), IL-1β, TNF-α, sTREM2, sCD14, TSPO-PET, C1q, and C3. | Persistent, weeks–months, and often plateauing if untreated. | Markers of maladaptive scarring and neuroinflammation; used to predict cognitive decline and network rigidity. | [165,166] |

| Senescence and chronic inflammation | Glial senescence, sustained inflammasome activation, and systemic immune dysregulation. | p16^INK4a, p21, IL-6, GDF15, HMGB1, NLRP3, Th17/Treg ratio, IL-17A, and sIL-2R. | Persistent, weeks–months, and associated with poor recovery trajectories. | Stratify risk of cognitive deterioration; potential targets for late-phase immunomodulation or senolytic therapies. | [167,168] |

| Secondary neurodegeneration | Wallerian degeneration, trans-synaptic spread, and delayed neuronal loss. | NfL, myelin-breakdown products, phosphorylated tau, Aβ42/40 ratio, and neurogranin. | Peaks weeks–months; may persist chronically. | Predicts progressive structural and cognitive decline; overlaps with neurodegenerative signatures and dementia risk. | [169,170] |

| Precision therapeutic windows | Composite biomarker panels, epigenetic clocks, and multi-omics state classification. | Multi-omics profiles (proteomic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic), CSPG-EVs, neurogenic miRNAs, and digital biomarkers. | Dynamic, longitudinal; inform evolving biological states. | Identify optimal therapy timing, guide intensity and modality selection, and support adaptive and personalized interventions. | [171,172] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Grigorean, V.T.; Pantu, C.; Breazu, A.; Oprea, S.; Munteanu, O.; Radoi, M.P.; Giuglea, C.; Marin, A. Mapping the Ischemic Continuum: Dynamic Multi-Omic Biomarker and AI for Personalized Stroke Care. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010502

Grigorean VT, Pantu C, Breazu A, Oprea S, Munteanu O, Radoi MP, Giuglea C, Marin A. Mapping the Ischemic Continuum: Dynamic Multi-Omic Biomarker and AI for Personalized Stroke Care. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):502. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010502

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrigorean, Valentin Titus, Cosmin Pantu, Alexandru Breazu, Stefan Oprea, Octavian Munteanu, Mugurel Petrinel Radoi, Carmen Giuglea, and Andrei Marin. 2026. "Mapping the Ischemic Continuum: Dynamic Multi-Omic Biomarker and AI for Personalized Stroke Care" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010502

APA StyleGrigorean, V. T., Pantu, C., Breazu, A., Oprea, S., Munteanu, O., Radoi, M. P., Giuglea, C., & Marin, A. (2026). Mapping the Ischemic Continuum: Dynamic Multi-Omic Biomarker and AI for Personalized Stroke Care. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010502