Preclinical Evaluation of Atorvastatin-Loaded PEGylated Liposomes in a Mouse Model of Traumatic Brain Injury

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

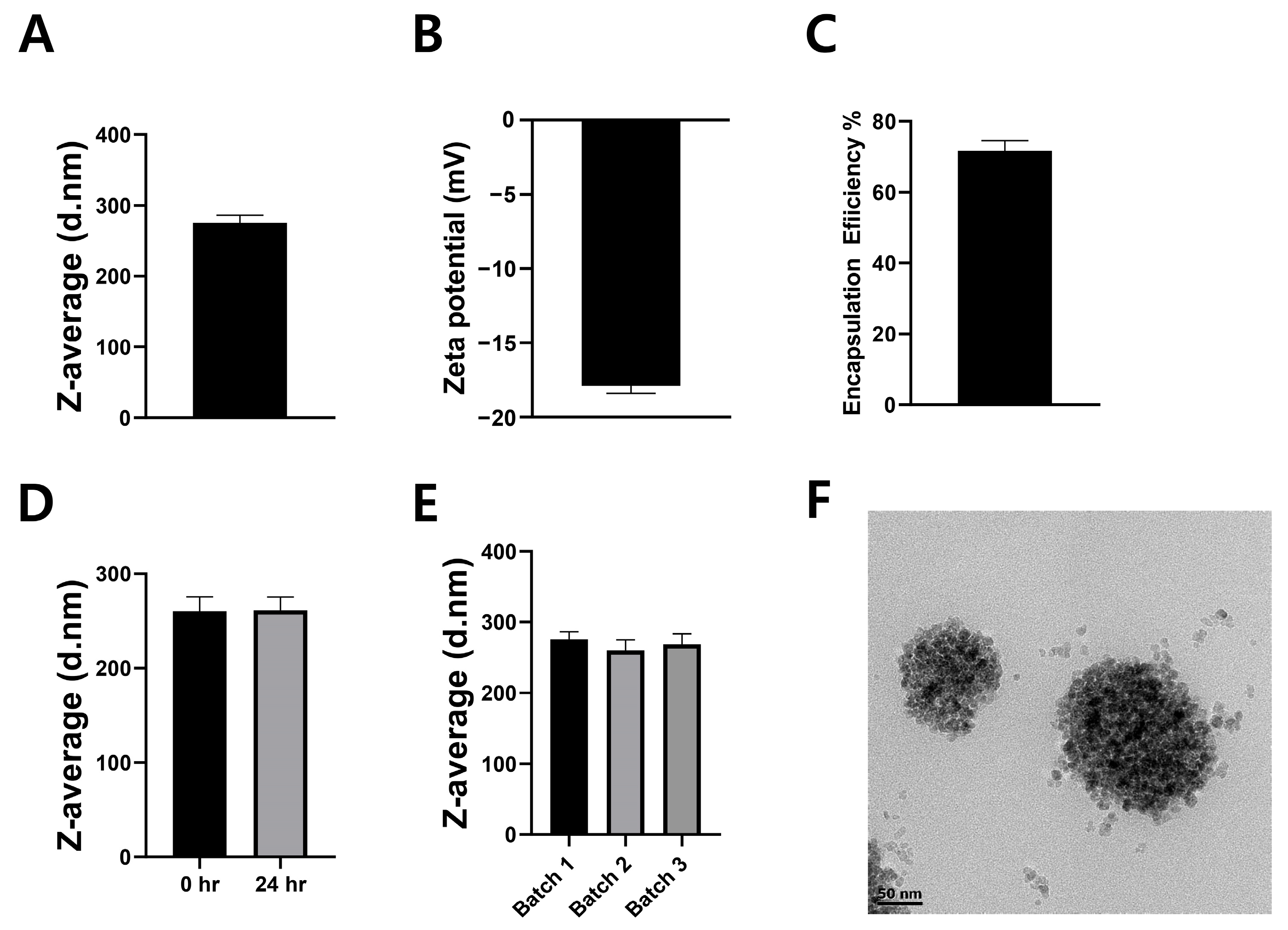

2.1. Physicochemical Characterization of LipoStatin Formulation

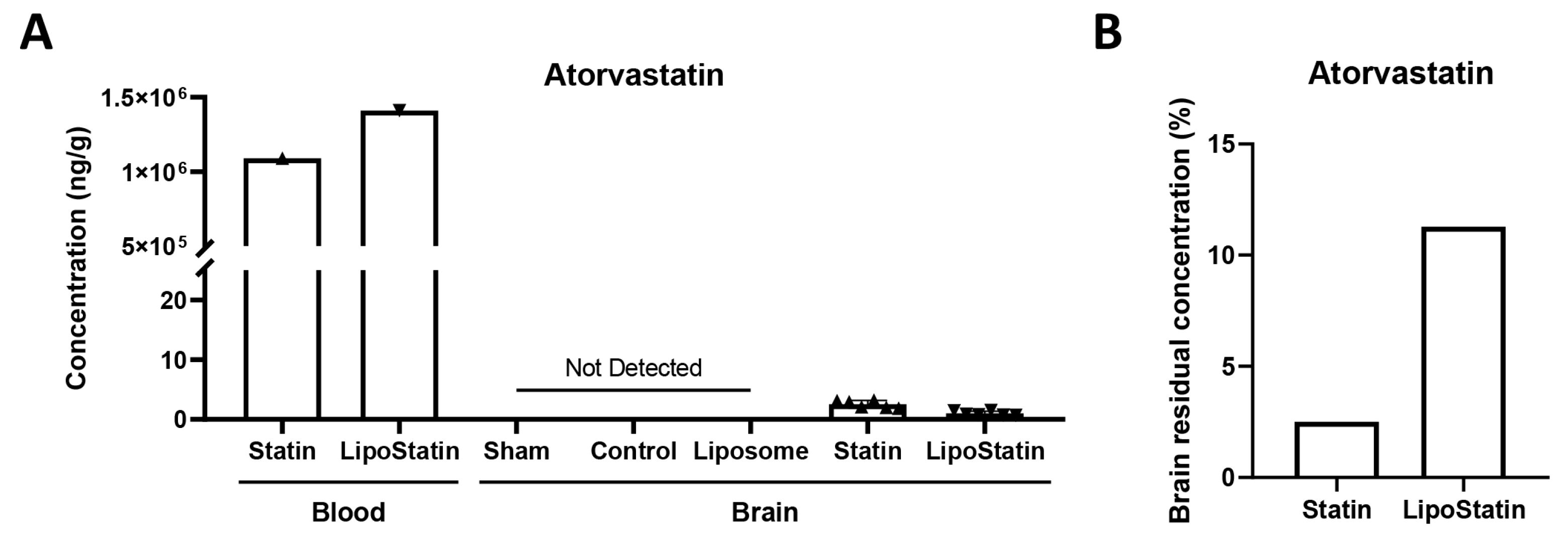

2.2. LC–MS Quantification of Atorvastatin Accumulation in Brain Tissue

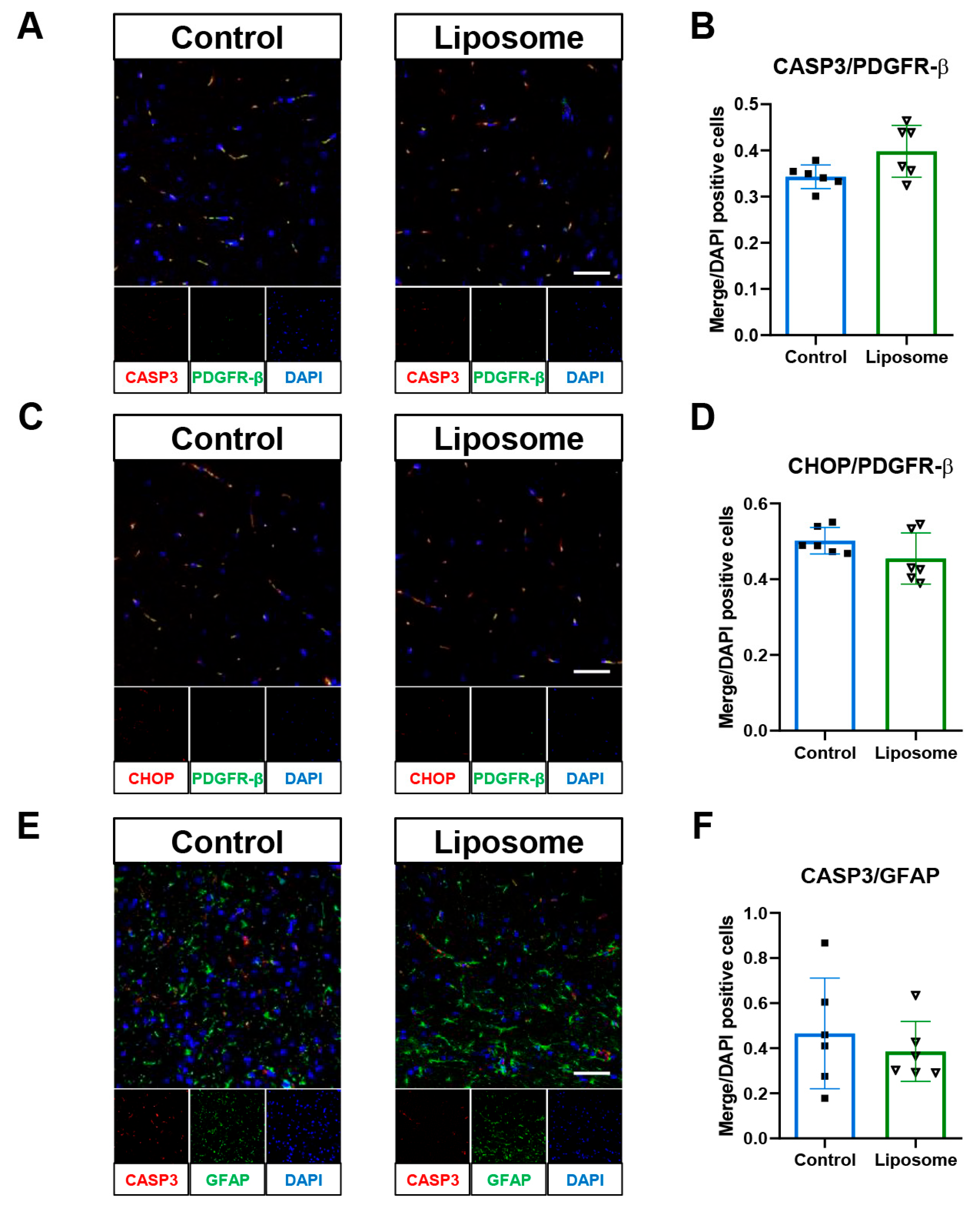

2.3. Evaluating the Impact of Empty Liposomes on TBI Outcomes

2.4. The LipoStatin Group Showed the Lowest NSS

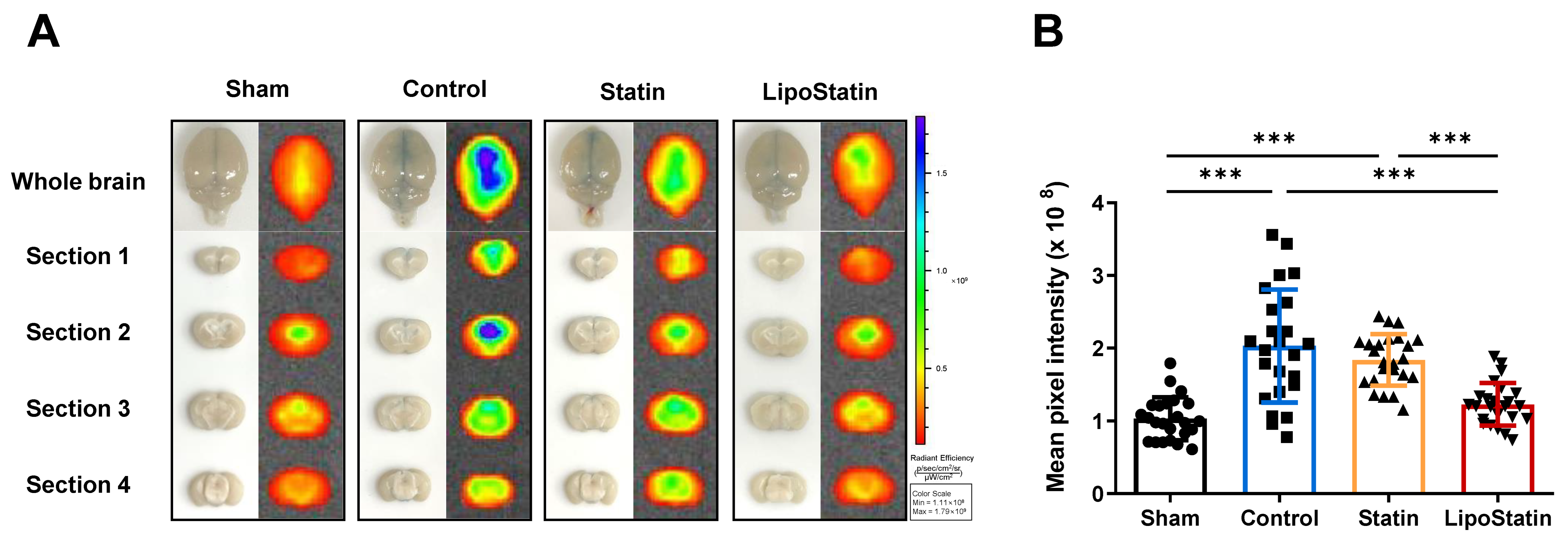

2.5. LipoStatin Treatment Significantly Decreased BBB Disruption

2.6. LipoStatin Restored Tight Junction Protein Levels

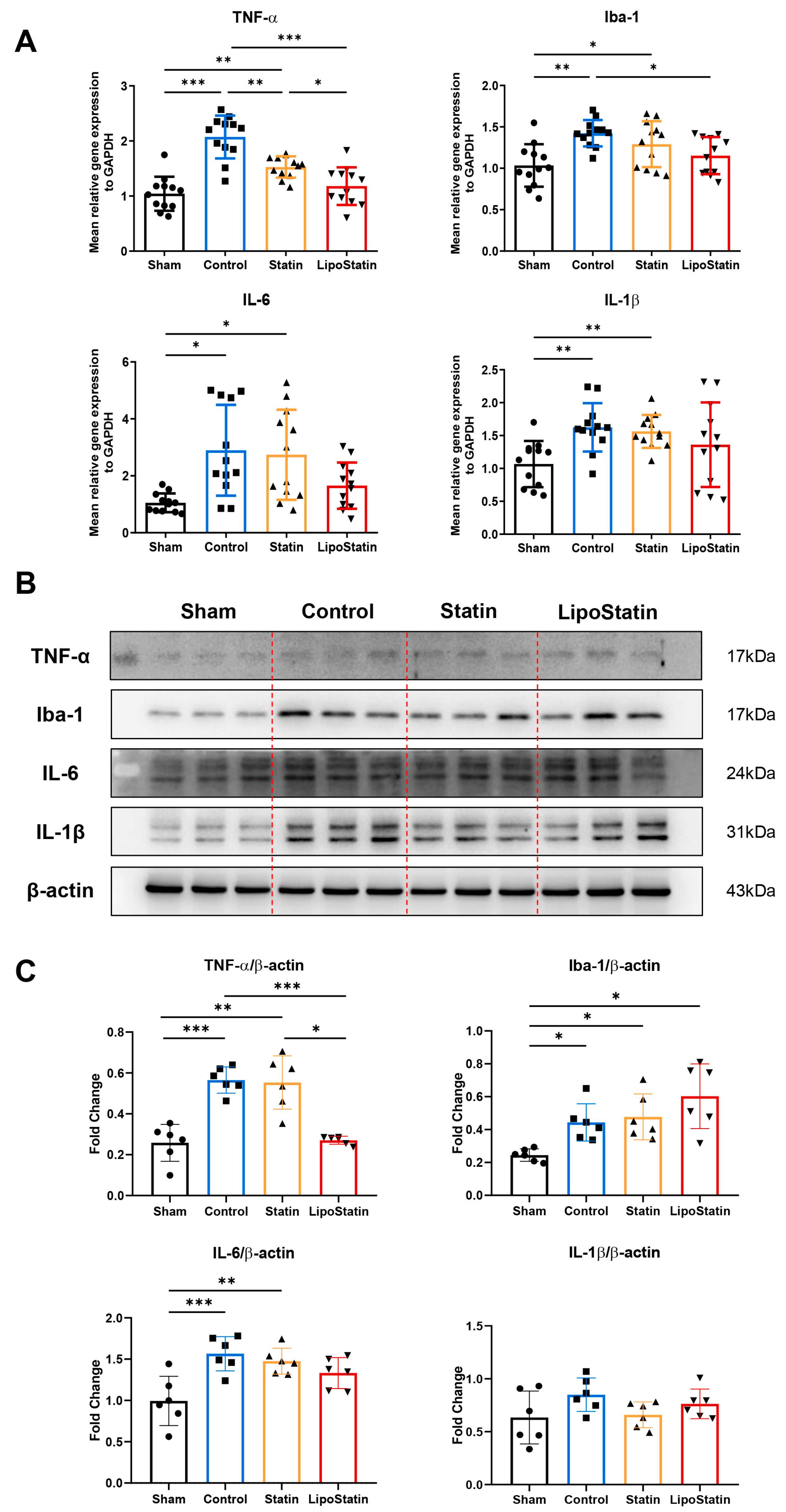

2.7. LipoStatin Reduced Inflammatory Cytokine Expression

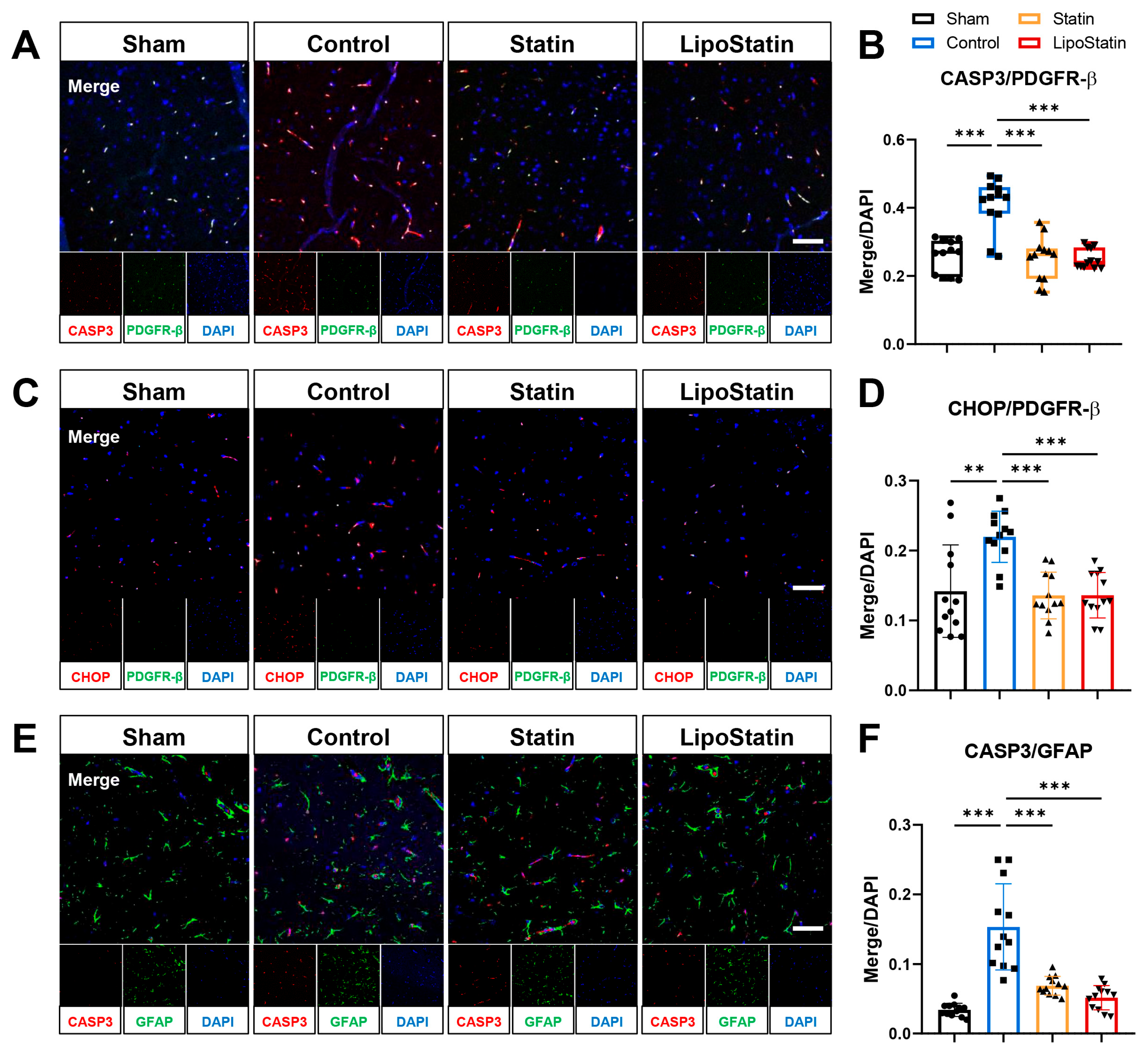

2.8. LipoStatin Affected Pericyte and Astrocyte Apoptosis

3. Discussion

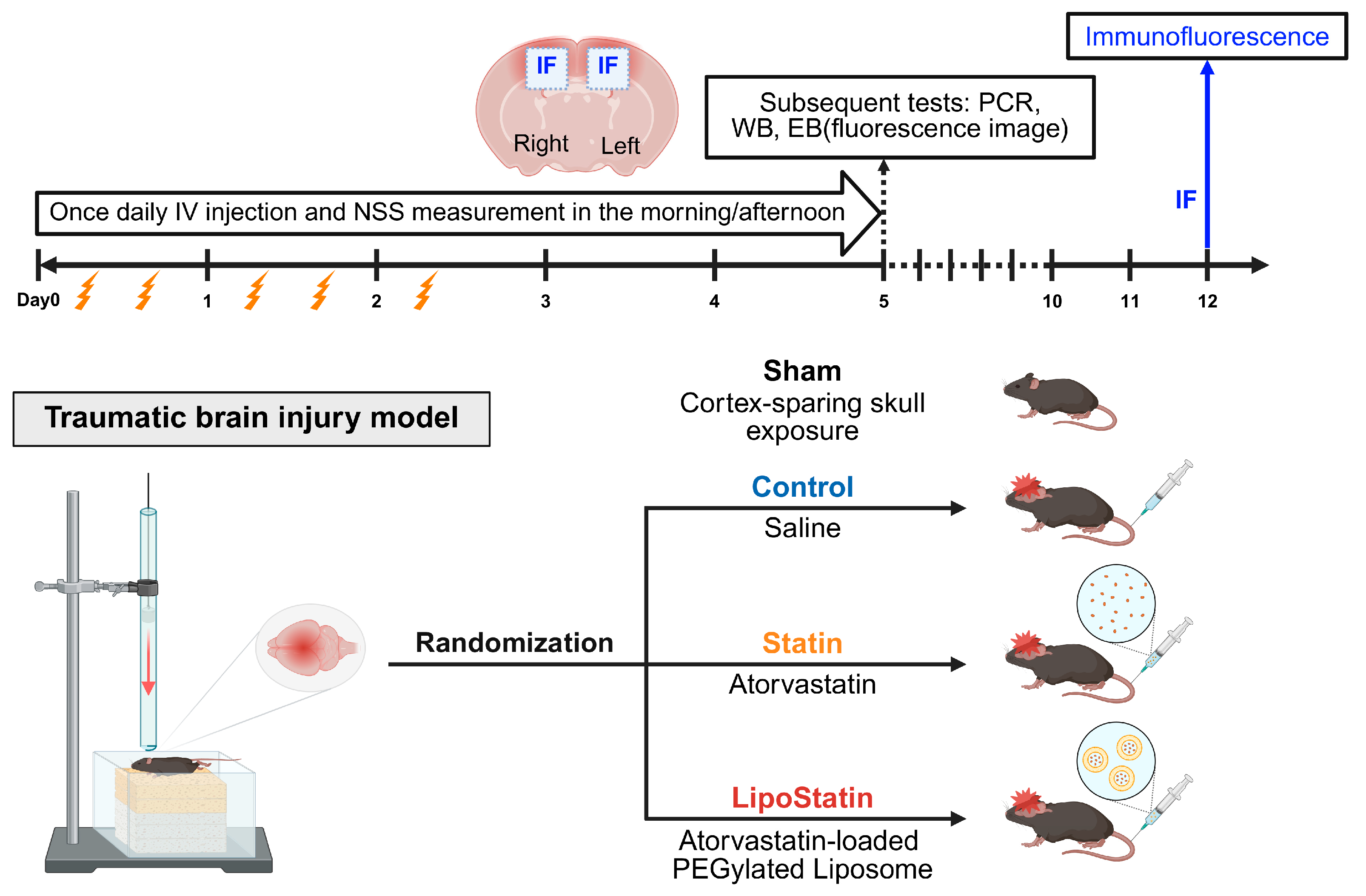

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Animals

4.2. Traumatic Brain Injury Model

4.3. Preparation and Characterization of LipoStatin

4.4. LC-MS/MS Analyses of Atorvastatin in Brain Tissue

4.5. Neurological Severity Score (NSS)

4.6. Evans Blue Staining and Fluorescence Imaging

4.7. Immunoblot Analyses and Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

4.8. Double Immunofluorescent Staining

4.9. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TBI | traumatic brain injury |

| PEG | polyethylene glycol |

| BBB | blood–brain barrier |

| NSS | neurological severity score |

| HMG-CoA | 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A |

| DSPE-PEG | 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine |

| DPPC | Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine |

| EB | Evans blue dye |

| IVIS | in vivo imaging system |

| ROI | Regions of interest |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| Iba-1 | ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 |

| IL-1β | interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | interleukin-6 |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| SD | standard deviation |

| rmTBI | repetitive mild traumatic brain injury |

References

- Guan, B.; Anderson, D.B.; Chen, L.; Feng, S.; Zhou, H. Global, regional and national burden of traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e075049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, A.I.R.; Menon, D.K.; Manley, G.T.; Abrams, M.; Akerlund, C.; Andelic, N.; Aries, M.; Bashford, T.; Bell, M.J.; Bodien, Y.G.; et al. Traumatic brain injury: Progress and challenges in prevention, clinical care, and research. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 1004–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvat, L.; Foschini, A.; Grinias, J.P.; Waterhouse, B.D.; Devilbiss, D.M. Repetitive mild traumatic brain injury impairs norepinephrine system function and psychostimulant responsivity. Brain Res. 2024, 1839, 149040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Xu, J.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, R. Hydrogel in the treatment of traumatic brain injury. Biomater. Res. 2024, 28, 0085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blennow, K.; Brody, D.L.; Kochanek, P.M.; Levin, H.; McKee, A.; Ribbers, G.M.; Yaffe, K.; Zetterberg, H. Traumatic brain injuries. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crupi, R.; Cordaro, M.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Impellizzeri, D. Management of traumatic brain injury: From present to future. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sironi, L.; Cimino, M.; Guerrini, U.; Calvio, A.M.; Lodetti, B.; Asdente, M.; Balduini, W.; Paoletti, R.; Tremoli, E. Treatment with statins after induction of focal ischemia in rats reduces the extent of brain damage. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003, 23, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, S.; Yamashita, T.; Miwa, Y.; Ozaki, M.; Namiki, M.; Hirase, T.; Inoue, N.; Hirata, K.; Yokoyama, M. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor has protective effects against stroke events in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Stroke 2003, 34, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Zeng, J.S.; Kreulen, D.L.; Kaufman, D.I.; Chen, A.F. Atorvastatin protects against cerebral infarction via inhibition of NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide in ischemic stroke. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006, 291, H2210–H2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Gao, W.; Cheng, S.; Yin, D.; Li, F.; Wu, Y.; Sun, D.; Zhou, S.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory mechanisms of atorvastatin in a murine model of traumatic brain injury. J. Neuroinflamm. 2017, 14, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.; Goussev, A.; Kazmi, H.; Qu, C.; Lu, D.; Chopp, M. Long-term benefits after treatment of traumatic brain injury with simvastatin in rats. Neurosurgery 2009, 65, 187–191; discussion 191–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, K.; Knight, R.A.; Han, Y.; Yang, D.; Zhang, J.; Ledbetter, K.A.; Chopp, M.; Seyfried, D.M. Simvastatin and atorvastatin improve neurological outcome after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 2009, 40, 3384–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfried, D.; Han, Y.; Lu, D.; Chen, J.; Bydon, A.; Chopp, M. Improvement in neurological outcome after administration of atorvastatin following experimental intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. J. Neurosurg. 2004, 101, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.H.; Chu, K.; Jeong, S.W.; Han, S.Y.; Lee, S.T.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, M.; Roh, J.K. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, atorvastatin, promotes sensorimotor recovery, suppressing acute inflammatory reaction after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 2004, 35, 1744–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, H.; Ghasemi, F.; Barreto, G.E.; Sathyapalan, T.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. The effects of statins on microglial cells to protect against neurodegenerative disorders: A mechanistic review. Biofactors 2020, 46, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, R.G.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.H.; Yoon, J.; Choi, K.H.; Jeong, Y.Y. Treatment of ischemic stroke by atorvastatin-loaded PEGylated liposome. Transl. Stroke Res. 2024, 15, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, T.M.; Tarini, D.; Dheen, S.T.; Bay, B.H.; Srinivasan, D.K. Nanoparticle-based technology approaches to the management of neurological disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubtow, M.M.; Oerter, S.; Quader, S.; Jeanclos, E.; Cubukova, A.; Krafft, M.; Haider, M.S.; Schulte, C.; Meier, L.; Rist, M.; et al. In Vitro blood-brain barrier permeability and cytotoxicity of an atorvastatin-loaded nanoformulation against glioblastoma in 2D and 3D models. Mol. Pharm. 2020, 17, 1835–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, F.S.; Omay, S.B.; Sheth, K.N.; Zhou, J. Nanoparticle-based drug delivery for the treatment of traumatic brain injury. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2023, 20, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, S.; Panghal, A.; Flora, S.J.S. Nanotechnology: A promising approach for delivery of neuroprotective drugs. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, K.R.; Pharasi, N.; Sarna, B.; Singh, M.; Rachana; Haider, S.; Singh, S.K.; Dua, K.; Jha, S.K.; Dey, A.; et al. Nanotechnology-based drug delivery for the treatment of CNS disorders. Transl. Neurosci. 2022, 13, 527–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, M.I.; Lopes, C.M.; Amaral, M.H.; Costa, P.C. Current insights on lipid nanocarrier-assisted drug delivery in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2020, 149, 192–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.J.; Cutler, E.G.; Cho, H. Therapeutic nanoplatforms and delivery strategies for neurological disorders. Nano Converg. 2018, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wang, Y.C.; Liu, Y.; Yue, Q.; Liu, Z.; Ke, M.; Zhao, S.; Li, C. Nanoagonist-mediated endothelial tight junction opening: A strategy for safely increasing brain drug delivery in mice. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2017, 37, 1410–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajes, M.; Ramos-Fernandez, E.; Weng-Jiang, X.; Bosch-Morato, M.; Guivernau, B.; Eraso-Pichot, A.; Salvador, B.; Fernandez-Busquets, X.; Roquer, J.; Munoz, F.J. The blood-brain barrier: Structure, function and therapeutic approaches to cross it. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2014, 31, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzon-Daza, M.L.; Campia, I.; Kopecka, J.; Garzon, R.; Ghigo, D.; Riganti, C. Nanoparticle- and liposome-carried drugs: New strategies for active targeting and drug delivery across blood-brain barrier. Curr. Drug Metab. 2013, 14, 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Teply, B.A.; Sherifi, I.; Sung, J.; Luther, G.; Gu, F.X.; Levy-Nissenbaum, E.; Radovic-Moreno, A.F.; Langer, R.; Farokhzad, O.C. Formulation of functionalized PLGA-PEG nanoparticles for in vivo targeted drug delivery. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 869–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, T.; Asai, T.; Oyama, D.; Agato, Y.; Yasuda, N.; Fukuta, T.; Shimizu, K.; Minamino, T.; Oku, N. Treatment of cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury with PEGylated liposomes encapsulating FK506. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 1362–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nenna, A.; Nappi, F.; Larobina, D.; Verghi, E.; Chello, M.; Ambrosio, L. Polymers and nanoparticles for statin delivery: Current use and future perspectives in cardiovascular disease. Polymers 2021, 13, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.H.; Kim, H.S.; Park, M.S.; Kim, J.T.; Kim, J.H.; Cho, K.A.; Lee, M.C.; Lee, H.J.; Cho, K.H. Regulation of caveolin-1 expression determines early brain edema after experimental focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke 2016, 47, 1336–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badaut, J.; Blochet, C.; Obenaus, A.; Hirt, L. Physiological and pathological roles of caveolins in the central nervous system. Trends Neurosci. 2024, 47, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.H.; Kim, H.S.; Park, M.S.; Lee, E.B.; Lee, J.K.; Kim, J.T.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, M.C.; Lee, H.J.; Cho, K.H. Overexpression of caveolin-1 attenuates brain edema by inhibiting tight junction degradation. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 67857–67867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwalkar, A.; Duncan, K.A. Otx2 mRNA expression is downregulated following traumatic brain injury in zebra finches. Front. Neural Circuits 2025, 19, 1591983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopperton, K.E.; Mohammad, D.; Trépanier, M.O.; Giuliano, V.; Bazinet, R.P. Markers of microglia in post-mortem brain samples from patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omondi, C.; Chou, A.; Fond, K.A.; Morioka, K.; Joseph, N.R.; Sacramento, J.A.; Iorio, E.; Torres-Espin, A.; Radabaugh, H.L.; Davis, J.A.; et al. Improving rigor and reproducibility in western blot experiments with the blotRig analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupcova Skalnikova, H.; Cizkova, J.; Cervenka, J.; Vodicka, P. Advances in proteomic techniques for cytokine analysis: Focus on melanoma research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Di, B.; Miao, J. Curcumol ameliorates neuroinflammation after cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury via affecting microglial polarization and Treg/Th17 balance through Nrf2/HO-1 and NF-κB signaling. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podell, J.; Yang, S.; Miller, S.; Felix, R.; Tripathi, H.; Parikh, G.; Miller, C.; Chen, H.; Kuo, Y.M.; Lin, C.Y.; et al. Rapid prediction of secondary neurologic decline after traumatic brain injury: A data analytic approach. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauchman, S.H.; Zubair, A.; Jacob, B.; Rauchman, D.; Pinkhasov, A.; Placantonakis, D.G.; Reiss, A.B. Traumatic brain injury: Mechanisms, manifestations, and visual sequelae. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1090672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Li, L.; Harris, O.A.; Luo, J. Blood-brain barrier disruption: A pervasive driver and mechanistic link between traumatic brain injury and Alzheimer’s disease. Transl. Neurodegener. 2025, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.H.; Ahmad, H.A.; Kim, H.; Nagareddy, R.; Choi, K.H.; Yoon, J.; Jeong, Y.Y. Effects of atorvastatin-loaded PEGylated liposomes delivered by magnetic stimulation for stroke treatment. Brain Stimul. 2025, 18, 1620–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronaldson, P.T.; Williams, E.I.; Betterton, R.D.; Stanton, J.A.; Nilles, K.L.; Davis, T.P. CNS drug delivery in stroke: Improving therapeutic translation from the bench to the bedside. Stroke 2024, 55, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanto, M.; Pangihutan Siahaan, A.M.; Wirjomartani, B.A.; Setiawan, H.; Aryanti, C.; Michael. The neuroprotective effect of statin in traumatic brain injury: A systematic review. World Neurosurg. X 2023, 19, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armulik, A.; Genove, G.; Mae, M.; Nisancioglu, M.H.; Wallgard, E.; Niaudet, C.; He, L.; Norlin, J.; Lindblom, P.; Strittmatter, K.; et al. Pericytes regulate the blood-brain barrier. Nature 2010, 468, 557–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glushakova, O.Y.; Glushakov, A.O.; Borlongan, C.V.; Valadka, A.B.; Hayes, R.L.; Glushakov, A.V. Role of caspase-3-mediated apoptosis in chronic caspase-3-cleaved tau accumulation and blood-brain barrier damage in the corpus callosum after traumatic brain Injury in rats. J. Neurotrauma 2018, 35, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, L.; Huang, L.; Zhao, C.; Ruan, Z. Valproic acid inhibits endoplasmic reticulum stress and reduces ferroptosis after traumatic brain injury. Dose Response 2024, 22, 15593258241303646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyyriainen, J.; Ekolle Ndode-Ekane, X.; Pitkanen, A. Dynamics of PDGFRbeta expression in different cell types after brain injury. Glia 2017, 65, 322–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burda, J.E.; Bernstein, A.M.; Sofroniew, M.V. Astrocyte roles in traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 275 Pt 3, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielefeld, P.; Martirosyan, A.; Martin-Suarez, S.; Apresyan, A.; Meerhoff, G.F.; Pestana, F.; Poovathingal, S.; Reijner, N.; Koning, W.; Clement, R.A.; et al. Traumatic brain injury promotes neurogenesis at the cost of astrogliogenesis in the adult hippocampus of male mice. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacs-Oller, T.; Zempleni, R.; Balogh, B.; Szarka, G.; Fazekas, B.; Tengolics, A.J.; Amrein, K.; Czeiter, E.; Hernadi, I.; Buki, A.; et al. Traumatic brain injury induces microglial and caspase3 activation in the retina. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babaee, A.; Eftekhar-Vaghefi, S.H.; Asadi-Shekaari, M.; Shahrokhi, N.; Soltani, S.D.; Malekpour-Afshar, R.; Basiri, M. Melatonin treatment reduces astrogliosis and apoptosis in rats with traumatic brain injury. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2015, 18, 867–872. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.K.; Maki, T.; Mandeville, E.T.; Koh, S.H.; Hayakawa, K.; Arai, K.; Kim, Y.M.; Whalen, M.J.; Xing, C.; Wang, X.; et al. Dual effects of carbon monoxide on pericytes and neurogenesis in traumatic brain injury. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 1335–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bylicky, M.A.; Mueller, G.P.; Day, R.M. Mechanisms of endogenous neuroprotective effects of astrocytes in brain injury. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 6501031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.J.; Chen, T.H.; Yang, L.Y.; Shih, C.M. Resveratrol protects astrocytes against traumatic brain injury through inhibiting apoptotic and autophagic cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gugliandolo, E.; D’Amico, R.; Cordaro, M.; Fusco, R.; Siracusa, R.; Crupi, R.; Impellizzeri, D.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Di Paola, R. Neuroprotective effect of artesunate in experimental model of traumatic brain injury. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, L.; Li, H.; Xie, Y.; Bai, J.; Guan, J.; Qi, H.; Sun, J. Targeted pathophysiological treatment of ischemic stroke using nanoparticle-based drug delivery system. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Jin, J.; Li, K.; Shi, L.; Wen, X.; Fang, F. Progresses and prospects of neuroprotective agents-loaded nanoparticles and biomimetic material in ischemic stroke. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 868323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, R.; Pathak, K. Statins therapy: A review on conventional and novel formulation approaches. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2011, 63, 983–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendieta, G.; Ben-Aicha, S.; Gutierrez, M.; Casani, L.; Arzanauskaite, M.; Carreras, F.; Sabate, M.; Badimon, L.; Vilahur, G. Intravenous statin administration during myocardial infarction compared with oral post-infarct administration. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 1386–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, S.; Eroglu, H.; Kurum, B.; Ulubayram, K. Brain targeting of atorvastatin loaded amphiphilic PLGA-b-PEG nanoparticles. J. Microencapsul. 2013, 30, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Martorell, M.; Cano-Sarabia, M.; Simats, A.; Hernandez-Guillamon, M.; Rosell, A.; Maspoch, D.; Montaner, J. Charge effect of a liposomal delivery system encapsulating simvastatin to treat experimental ischemic stroke in rats. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 3035–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarizadeh, A.; Butler, A.E.; Badiee, A.; Sahebkar, A. Liposomal nanocarriers for statins: A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics appraisal. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Khan, S.; Wei, R.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wee Yong, V.; Xue, M. Application of nanomaterials in the treatment of intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Tissue Eng. 2023, 14, 20417314231157004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Lv, W.; Wu, L.; Wang, B.; Lv, L.; Xu, Q.; Xin, H. Enhanced anti-ischemic stroke of ZL006 by T7-conjugated PEGylated liposomes drug delivery system. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toljan, K.; Ashok, A.; Labhasetwar, V.; Hussain, M.S. Nanotechnology in stroke: New trails with smaller scales. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namiot, E.D.; Sokolov, A.V.; Chubarev, V.N.; Tarasov, V.V.; Schioth, H.B. Nanoparticles in clinical trials: Analysis of clinical trials, FDA approvals and use for COVID-19 vaccines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuta, T.; Oku, N.; Kogure, K. Application and utility of liposomal neuroprotective agents and biomimetic nanoparticles for the treatment of ischemic stroke. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, S.; Malik, R.; Singh, G.; Bhatia, S.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Mohan, S.; Albratty, M.; Albarrati, A.; Tambuwala, M.M. Pathogenesis and management of traumatic brain injury (TBI): Role of neuroinflammation and anti-inflammatory drugs. Inflammopharmacology 2022, 30, 1153–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.H.; Dunn, K.W. Statistical tests for measures of colocalization in biological microscopy. J. Microsc. 2013, 252, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmarou, A.; Foda, M.A.; van den Brink, W.; Campbell, J.; Kita, H.; Demetriadou, K. A new model of diffuse brain injury in rats. Part I: Pathophysiology and biomechanics. J. Neurosurg. 1994, 80, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flierl, M.A.; Stahel, P.F.; Beauchamp, K.M.; Morgan, S.J.; Smith, W.R.; Shohami, E. Mouse closed head injury model induced by a weight-drop device. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 1328–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, R.G.; Cooney, S.J.; Khayrullina, G.; Hockenbury, N.; Wilson, C.M.; Jaiswal, S.; Bermudez, S.; Armstrong, R.C.; Byrnes, K.R. Outcome after repetitive mild traumatic brain injury is temporally related to glucose uptake profile at time of second injury. J. Neurotrauma 2016, 33, 1479–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, M.J.; Angoa-Perez, M.; Briggs, D.I.; Viano, D.C.; Kreipke, C.W.; Kuhn, D.M. A mouse model of human repetitive mild traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosci. Methods 2012, 203, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shitaka, Y.; Tran, H.T.; Bennett, R.E.; Sanchez, L.; Levy, M.A.; Dikranian, K.; Brody, D.L. Repetitive closed-skull traumatic brain injury in mice causes persistent multifocal axonal injury and microglial reactivity. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2011, 70, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kho, A.R.; Hong, D.K.; Kang, B.S.; Park, W.J.; Choi, K.C.; Park, K.H.; Suh, S.W. The effects of atorvastatin on global cerebral ischemia-induced neuronal death. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, Q.; Cao, H.; Zhong, W.; Ding, B.; Tang, X. Atorvastatin protects against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury through anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. Neural Regen. Res. 2014, 9, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsenter, J.; Beni-Adani, L.; Assaf, Y.; Alexandrovich, A.G.; Trembovler, V.; Shohami, E. Dynamic changes in the recovery after traumatic brain injury in mice: Effect of injury severity on T2-weighted MRI abnormalities, and motor and cognitive functions. J. Neurotrauma 2008, 25, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaenko, A.; Chen, H.; Kammer, J.; Zhang, J.H.; Tang, J. Comparison Evans Blue injection routes: Intravenous versus intraperitoneal, for measurement of blood-brain barrier in a mice hemorrhage model. J. Neurosci. Methods 2011, 195, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hwang, E.-S.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, J.-H.; Nagareddy, R.; Jeong, Y.-Y.; Choi, K.-H. Preclinical Evaluation of Atorvastatin-Loaded PEGylated Liposomes in a Mouse Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412176

Hwang E-S, Kim J-H, Kim J-H, Nagareddy R, Jeong Y-Y, Choi K-H. Preclinical Evaluation of Atorvastatin-Loaded PEGylated Liposomes in a Mouse Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412176

Chicago/Turabian StyleHwang, Eun-Sol, Ja-Hae Kim, Ji-Hye Kim, Raveena Nagareddy, Yong-Yeon Jeong, and Kang-Ho Choi. 2025. "Preclinical Evaluation of Atorvastatin-Loaded PEGylated Liposomes in a Mouse Model of Traumatic Brain Injury" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412176

APA StyleHwang, E.-S., Kim, J.-H., Kim, J.-H., Nagareddy, R., Jeong, Y.-Y., & Choi, K.-H. (2025). Preclinical Evaluation of Atorvastatin-Loaded PEGylated Liposomes in a Mouse Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412176