Gyrase and Topoisomerase IV as Antibacterial Targets for Gepotidacin and Zoliflodacin: Teaching Old Enzymes New Tricks

Abstract

1. Introduction

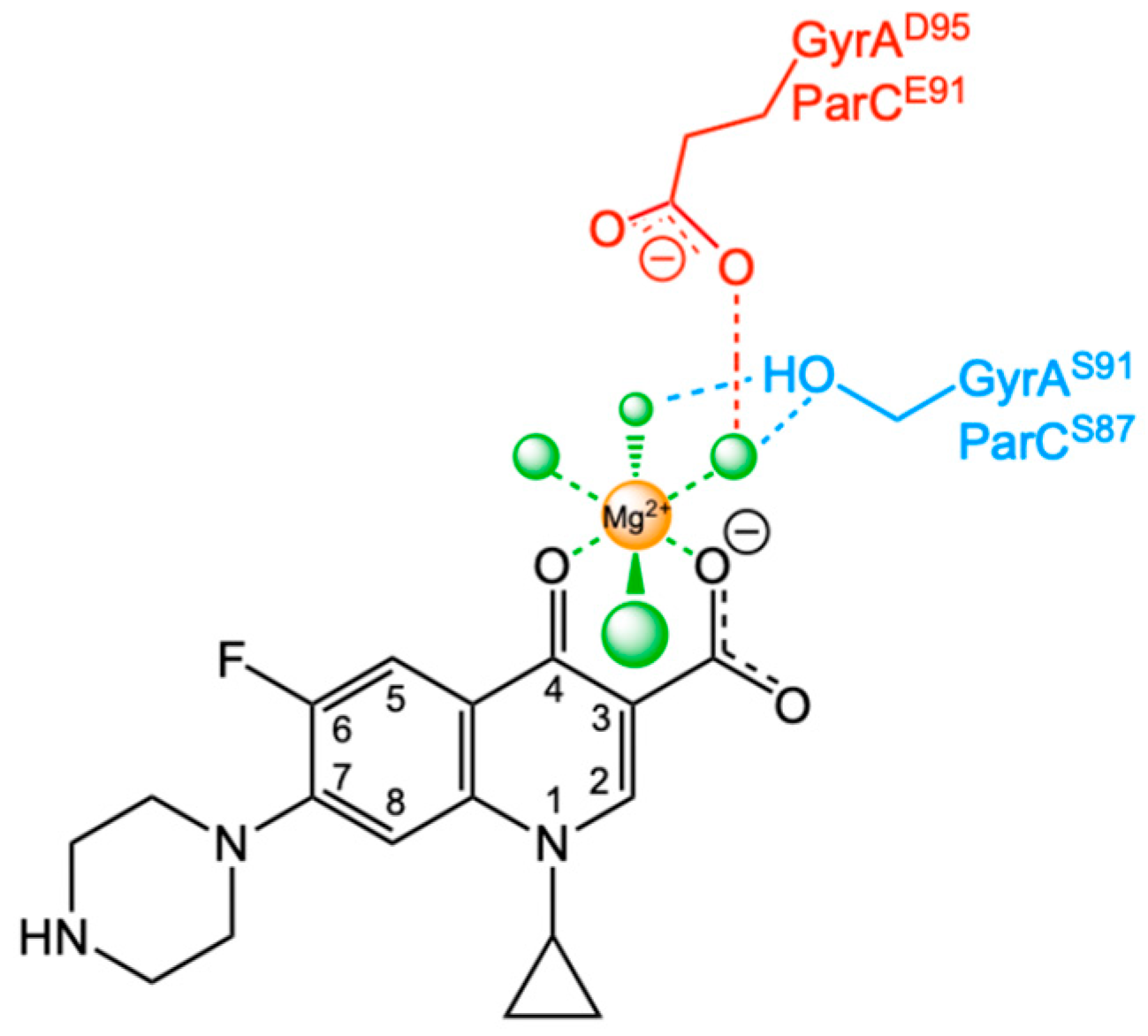

2. Fluoroquinolones

3. Novel Gyrase/Topoisomerase IV-Targeted Antibacterials

3.1. Gepotidacin

3.2. Zoliflodacin

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, S.H.; Chan, N.L.; Hsieh, T.S. New mechanistic and functional insights into DNA topoisomerases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013, 82, 139–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, E.G.; Ashley, R.E.; Kerns, R.J.; Osheroff, N. Fluoroquinolone interactions with bacterial type II topoisomerases and target-mediated drug resistance. In Antimicrobial Resistance in the 21st Century, 2nd ed.; Drlica, K., Shlaes, D., Fong, I.W., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 507–529. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley, R.E.; Osheroff, N. Regulation of DNA by topoisomerases: Mathematics at the molecular level. In Knots, Low-Dimensional Topology and Applications; Adams, C.C., Gordon, C.M., Jones, V.F.R., Kauffman, L.H., Lambropoulou, S., Millet, K.C., Przytycki, J.H., Ricca, R., Sazdanovic, R., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 411–433. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, N.G.; Diez-Santos, I.; Abbott, L.R.; Maxwell, A. Quinolones: Mechanism, lethality and their contributions to antibiotic resistance. Molecules 2020, 25, 5662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKie, S.J.; Neuman, K.C.; Maxwell, A. DNA topoisomerases: Advances in understanding of cellular roles and multi-protein complexes via structure-function analysis. Bioessays 2021, 43, 2000286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.A.; Osheroff, N. Gyrase and topoisomerase IV: Recycling old targets for new antibacterials to combat fluoroquinolone resistance. ACS Infect. Dis. 2024, 10, 1097–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldred, K.J.; Kerns, R.J.; Osheroff, N. Mechanism of quinolone action and resistance. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 1565–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, R.T.; Dougherty, T.J.; Fraimow, H.S.; Bellin, E.Y.; Miller, M.H. Association between early inhibition of DNA synthesis and the MICs and MBCs of carboxyquinolone antimicrobial agents for wild-type and mutant [gyrA nfxB(ompF) acrA] Escherichia coli K-12. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1988, 32, 1113–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommier, Y. Drugging topoisomerases: Lessons and challenges. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, D.C.; Jacoby, G.A. Mechanisms of drug resistance: Quinolone resistance. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1354, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiasa, H. DNA topoisomerases as targets for antibacterial agents. In DNA Topoisomerases; Drolet, M., Ed.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 1703, pp. 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, T.D.M.; Ziora, Z.M.; Blaskovich, M.A.T. Quinolone antibiotics. Med. Chem. Commun. 2019, 10, 1719–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bax, B.D.; Murshudov, G.; Maxwell, A.; Germe, T. DNA topoisomerase inhibitors: Trapping a DNA-cleaving machine in motion. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 3427–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outpatient Antibiotic Prescriptions—United States, 2017; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017.

- Basarab, G.S. Four ways to skin a cat: Inhibition of bacterial topoisomerases leading to the clinic. In Antibacterials: Volume I; Fisher, J.F., Mobashery, S., Miller, M.J., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 165–188. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Advisory Group on Integrated Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance. Critically Important Antimicrobials for Human Medicine, 6th Revision; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Buehrle, D.J.; Wagener, M.M.; Clancy, C.J. Outpatient fluoroquinolone prescription fills in the United States, 2014 to 2020: Assessing the impact of Food and Drug Administration safety warnings. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e0015121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlkonig, A.; Chan, P.F.; Fosberry, A.P.; Homes, P.; Huang, J.; Kranz, M.; Leydon, V.R.; Miles, T.J.; Pearson, N.D.; Perera, R.L.; et al. Structural basis of quinolone inhibition of type IIA topoisomerases and target-mediated resistance. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010, 17, 1152–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, H.; Kojima, T.; Yamagishi, J.; Nakamura, S. Quinolone-resistant mutations of the gyrA gene of Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1988, 211, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, M.E.; Wyke, A.W.; Kuroda, R.; Fisher, L.M. Cloning and characterization of a DNA gyrase A gene from Escherichia coli that confers clinical resistance to 4-quinolones. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1989, 33, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heisig, P.; Schedletzky, H.; Falkensteinpaul, H. Mutations in the gyrA gene of a highly fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolate of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1993, 37, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldred, K.J.; McPherson, S.A.; Wang, P.; Kerns, R.J.; Graves, D.E.; Turnbough, C.L.; Osheroff, N. Drug interactions with Bacillus anthracis topoisomerase IV: Biochemical basis for quinolone action and resistance. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldred, K.J.; McPherson, S.A.; Turnbough, C.L.; Kerns, R.J.; Osheroff, N. Topoisomerase IV-quinolone interactions are mediated through a water-metal ion bridge: Mechanistic basis of quinolone resistance. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 4628–4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldred, K.J.; Breland, E.J.; Vlčková, V.; Strub, M.P.; Neuman, K.C.; Kerns, R.J.; Osheroff, N. Role of the water-metal ion bridge in mediating interactions between quinolones and Escherichia coli topoisomerase IV. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 5558–5567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, H.E.; Wildman, B.; Schwanz, H.A.; Kerns, R.J.; Aldred, K.J. Role of the water-metal ion bridge in quinolone interactions with Escherichia coli gyrase. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redgrave, L.S.; Sutton, S.B.; Webber, M.A.; Piddock, L.J. Fluoroquinolone resistance: Mechanisms, impact on bacteria, and role in evolutionary success. Trends Microbiol. 2014, 22, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, L.; Cameron, B.; Crouzet, J. Analysis of gyrA and grlA mutations in stepwise-selected ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1995, 39, 1554–1558, Erratum in Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1995, 39, 2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.S.; Ambler, J.; Mehtar, S.; Fisher, L.M. Involvement of topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase as ciprofloxacin targets in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1996, 40, 2321–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, B.; Zhao, X.; Lu, T.; Drlica, K.; Hooper, D.C. Selective targeting of topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase in Staphylococcus aureus: Different patterns of quinolone-induced inhibition of DNA synthesis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 2160–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bax, B.D.; Chan, P.F.; Eggleston, D.S.; Fosberry, A.; Gentry, D.R.; Gorrec, F.; Giordano, I.; Hann, M.M.; Hennessy, A.; Hibbs, M.; et al. Type IIA topoisomerase inhibition by a new class of antibacterial agents. Nature 2010, 466, 935–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, E.G.; Bax, B.; Chan, P.F.; Osheroff, N. Mechanistic and structural basis for the actions of the antibacterial gepotidacin against Staphylococcus aureus gyrase. ACS Infect. Dis. 2019, 5, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanden Broeck, A.; Lotz, C.; Ortiz, J.; Lamour, V. Cryo-EM structure of the complete E. coli DNA gyrase nucleoprotein complex. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oviatt, A.A.; Gibson, E.G.; Huang, J.; Mattern, K.; Neuman, K.; Chan, P.F.; Osheroff, N. Interactions between gepotidacin and Escherichia coli gyrase and topoisomerase IV: Genetic and biochemical evidence for well-balanced dual targeting. ACS Infect. Dis. 2024, 10, 1137–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Papa, J.L.; Nolan, S.; English, A.; Seffernick, J.T.; Shkolnikov, N.; Powell, J.; Lindert, S.; Wozniak, D.J.; Yalowich, J.; et al. Dioxane-linked amide derivatives as novel bacterial topoisomerase inhibitors against gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 2446–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.R.; Mann, C.A.; Nolan, S.; Collins, J.A.; Parker, E.; Papa, J.; Vibhute, S.; Jahanbakhsh, S.; Thwaites, M.; Hufnagel, D.; et al. 1,3-Dioxane-linked novel bacterial topoisomerase inhibitors: Expanding structural diversity and the antibacterial spectrum. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviatt, A.A.; Collins, J.A.; Mann, C.A.; Huang, J.; Mattern, K.; Chan, P.F.; Osheroff, N. Mechanism of action of gepotidacin: Well-balanced dual-targeting against Neisseria gonorrhoeae gyrase and topoisomerase IV in cells and in vitro. ACS Infect. Dis. 2025, 11, 3093–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, C.A.; Halasohoris, S.A.; Gray, A.M.; Chua, J.; Spencer, J.L.; Curry, B.J.; Babyak, A.L.; Klimko, C.P.; Cote, C.K.; West, J.S.; et al. Activities of the novel bacterial topoisomerase inhibitor OSUAB-0284 against the biothreat pathogen Bacillus anthracis and its type II topoisomerases. ACS Infec. Dis. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayar, A.S.; Dougherty, T.J.; Reck, F.; Thresher, J.; Gao, N.; Shapiro, A.B.; Ehmann, D.E. Target-based resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli to NBTI 5463, a novel bacterial type II topoisomerase inhibitor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szili, P.; Draskovits, G.; Revesz, T.; Bogar, F.; Balogh, D.; Martinek, T.; Daruka, L.; Spohn, R.; Vasarhelyi, B.M.; Czikkely, M.; et al. Rapid evolution of reduced susceptibility against a balanced dual-targeting antibiotic through stepping-stone mutations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e00207-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.D.C.; Wilson, J.; Workowski, K.A.; Taylor, S.N.; Lewis, D.A.; Gatsi, S.; Flight, W.; Scangarella-Oman, N.E.; Jakielaszek, C.; Lythgoe, D.; et al. Oral gepotidacin for the treatment of uncomplicated urogenital gonorrhoea (EAGLE-1): A phase 3 randomised, open-label, non-inferiority, multicentre study. Lancet 2025, 405, 1608–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenlehner, F.; Perry, C.R.; Hooton, T.M.; Scangarella-Oman, N.E.; Millns, H.; Powell, M.; Jarvis, E.; Dennison, J.; Sheets, A.; Butler, D.; et al. Oral gepotidacin versus nitrofurantoin in patients with uncomplicated urinary tract infection (EAGLE-2 and EAGLE-3): Two randomised, controlled, double-blind, double-dummy, phase 3, non-inferiority trials. Lancet 2024, 403, 741–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullard, A. New antibiotic for urinary tract infections nabs FDA approval. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2025, 24, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GlaxoSmithKline Blujepa (Gepotidacin) Approved by US FDA for Treatment of Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections (uUTIs) in Female Adults and Paediatric Patients 12 Years of Age and Older. Available online: https://www.gsk.com/en-gb/media/press-releases/blujepa-gepotidacin-approved-by-us-fda-for-treatment-of-uncomplicated-urinary-tract-infections/ (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. MHRA Approves UK’s First New Type of Antibiotic for Urinary Tract Infections in Nearly 30 Years. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/mhra-approves-uks-first-new-type-of-antibiotic-for-urinary-tract-infections-in-nearly-30-years (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Simmering, J.E.; Tang, F.; Cavanaugh, J.E.; Polgreen, L.A.; Polgreen, P.M. The increase in hospitalizations for urinary tract infections and the associated costs in the United States, 1998–2011. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2017, 4, ofw281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, M.; Castillo-Pino, E. An introduction to the epidemiology and burden of urinary tract infections. Ther. Adv. Urol. 2019, 11, 1756287219832172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, R.; Murt, A. Epidemiology of urological infections: A global burden. World J. Urol. 2020, 38, 2669–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GlaxoSmithKline Blujepa (Gepotidacin) Approved by US FDA as Oral Option for Treatment of Uncomplicated Urogenital Gonorrhoea (uGC). Available online: https://www.gsk.com/en-gb/media/press-releases/blujepa-gepotidacin-approved-by-us-fda-as-oral-option-for-treatment-of-uncomplicated-urogenital-gonorrhoea-ugc/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Quillin, S.J.; Seifert, H.S. Neisseria gonorrhoeae host adaptation and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Web annex 1: Key data at a glance. In Global Progress Report on HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2021; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Gonorrhoea (Neisseria gonorrhoeae Infection); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Koebler, J. World Health Organization Warns Gonorrhea Could Join HIV as ‘Uncurable’. Available online: https://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2012/06/06/world-health-organization-warns-gonorrhea-could-join-hiv-as-uncurable- (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- World Health Organization. WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2024: Bacterial Pathogens of Public Health Importance to Guide Research, Development and Strategies to Prevent and Control Antimicrobial Resistance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Unemo, M.; Seifert, H.S.; Hook, E.W., 3rd; Hawkes, S.; Ndowa, F.; Dillon, J.R. Gonorrhoea. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, J.S.; Levine, W.C. Drugs of choice for the treatment of uncomplicated gonococcal infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1995, 20, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dan, M. The use of fluoroquinolones in gonorrhoea: The increasing problem of resistance. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2004, 5, 829–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update to CDC’s sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006: Fluoroquinolones no longer recommended for treatment of gonococcal infections. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2007, 56, 332–336. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2020–2021: Annual Perspective; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2023.

- Unemo, M.; Lahra, M.M.; Escher, M.; Eremin, S.; Cole, M.J.; Galarza, P.; Ndowa, F.; Martin, I.; Dillon, J.R.; Galas, M.; et al. WHO global antimicrobial resistance surveillance for Neisseria gonorrhoeae 2017-18: A retrospective observational study. Lancet Microbe 2021, 2, e627–e636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, P.F.; Srikannathasan, V.; Huang, J.; Cui, H.; Fosberry, A.P.; Gu, M.; Hann, M.M.; Hibbs, M.; Homes, P.; Ingraham, K.; et al. Structural basis of DNA gyrase inhibition by antibacterial QPT-1, anticancer drug etoposide and moxifloxacin. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, H.; Lipka-Lloyd, M.; Warren, A.J.; Hughes, N.; Holmes, J.; Burton, N.P.; Mahenthiralingam, E.; Bax, B.D. A 2.8 Å structure of zoliflodacin in a DNA cleavage complex with Staphylococcus aureus DNA gyrase. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, G.; Palmer, T.; Ehmann, D.E.; Shapiro, A.B.; Andrews, B.; Basarab, G.S.; Doig, P.; Fan, J.; Gao, N.; Mills, S.D.; et al. Inhibition of Neisseria gonorrhoeae type II topoisomerases by the novel spiropyrimidinetrione AZD0914. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 20984–20994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.A.; Basarab, G.S.; Chibale, K.; Osheroff, N. Interactions between zoliflodacin and Neisseria gonorrhoeae gyrase and topoisomerase IV: Enzymological basis for cellular targeting. ACS Infect. Dis. 2024, 10, 3071–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, R.A.; Lahiri, S.D.; Kutschke, A.; Otterson, L.G.; McLaughlin, R.E.; Whiteaker, J.D.; Lewis, L.A.; Su, X.; Huband, M.D.; Gardner, H.; et al. Characterization of the novel DNA gyrase inhibitor AZD0914: Low resistance potential and lack of cross-resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 1478–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huband, M.D.; Bradford, P.A.; Otterson, L.G.; Basarab, G.S.; Kutschke, A.C.; Giacobbe, R.A.; Patey, S.A.; Alm, R.A.; Johnstone, M.R.; Potter, M.E.; et al. In vitro antibacterial activity of AZD0914, a new spiropyrimidinetrione DNA gyrase/topoisomerase inhibitor with potent activity against Gram-positive, fastidious Gram-negative, and atypical bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unemo, M.; Ringlander, J.; Wiggins, C.; Fredlund, H.; Jacobsson, S.; Cole, M. High in vitro susceptibility to the novel spiropyrimidinetrione ETX0914 (AZD0914) among 873 contemporary clinical Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates from 21 European countries from 2012 to 2014. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 5220–5225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biedenbach, D.J.; Bouchillon, S.K.; Hackel, M.; Miller, L.A.; Scangarella-Oman, N.E.; Jakielaszek, C.; Sahm, D.F. In vitro activity of gepotidacin, a novel triazaacenaphthylene bacterial topoisomerase inhibitor, against a broad spectrum of bacterial pathogens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 1918–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, J.R.; Lawrence, K.; Sharpe, S.; Mueller, J.; Kirkcaldy, R.D. In vitro growth of multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates is inhibited by ETX0914, a novel spiropyrimidinetrione. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2016, 48, 328–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unemo, M.; Ahlstrand, J.; Sanchez-Buso, L.; Day, M.; Aanensen, D.; Golparian, D.; Jacobsson, S.; Cole, M.J.; European Collaborative, G. High susceptibility to zoliflodacin and conserved target (GyrB) for zoliflodacin among 1209 consecutive clinical Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates from 25 European countries, 2018. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govender, P.; Muller, R.; Singh, K.; Reddy, V.; Eyermann, C.J.; Fienberg, S.; Ghorpade, S.R.; Koekemoer, L.; Myrick, A.; Schnappinger, D.; et al. Spiropyrimidinetrione DNA gyrase inhibitors with potent and selective antituberculosis activity. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 6903–6925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basarab, G.S.; Ghorpade, S.; Gibhard, L.; Mueller, R.; Njoroge, M.; Peton, N.; Govender, P.; Massoudi, L.M.; Robertson, G.T.; Lenaerts, A.J.; et al. Spiropyrimidinetriones: A class of DNA gyrase inhibitors with activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and without cross-resistance to fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e0219221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byl, J.A.W.; Mueller, R.; Bax, B.; Basarab, G.S.; Chibale, K.; Osheroff, N. A series of spiropyrimidinetriones that enhances DNA cleavage mediated by Mycobacterium tuberculosis gyrase. ACS Infect. Dis. 2023, 9, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckey, A.; Balasegaram, M.; Barbee, L.A.; Batteiger, T.A.; Broadhurst, H.; Cohen, S.E.; Delany-Moretlwe, S.; de Vries, H.J.C.; Dionne, J.A.; Gill, K.; et al. Zoliflodacin versus ceftriaxone plus azithromycin for treatment of uncomplicated urogenital gonorrhoea: An international, randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3, non-inferiority clinical trial. Lancet 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Antibiotic Research & Development Partnership. NUZOLVENCE® (Zoliflodacin), First-in-Class Oral Antibiotic for Gonorrhoea, Receives U.S. FDA Approval. Available online: https://gardp.org/nuzolvence-zoliflodacin-first-in-class-oral-antibiotic-for-gonorrhoea-receives-u-s-fda-approval/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves Two Oral Therapies to Treat Gonorrhea. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-two-oral-therapies-treat-gonorrhea (accessed on 12 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Osheroff, N. Gyrase and Topoisomerase IV as Antibacterial Targets for Gepotidacin and Zoliflodacin: Teaching Old Enzymes New Tricks. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010496

Osheroff N. Gyrase and Topoisomerase IV as Antibacterial Targets for Gepotidacin and Zoliflodacin: Teaching Old Enzymes New Tricks. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010496

Chicago/Turabian StyleOsheroff, Neil. 2026. "Gyrase and Topoisomerase IV as Antibacterial Targets for Gepotidacin and Zoliflodacin: Teaching Old Enzymes New Tricks" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010496

APA StyleOsheroff, N. (2026). Gyrase and Topoisomerase IV as Antibacterial Targets for Gepotidacin and Zoliflodacin: Teaching Old Enzymes New Tricks. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 496. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010496