Fingolimod Effects on Motor Function and BDNF-TrkB Signaling in a Huntington’s Mouse Model Are Disease-Stage-Dependent

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

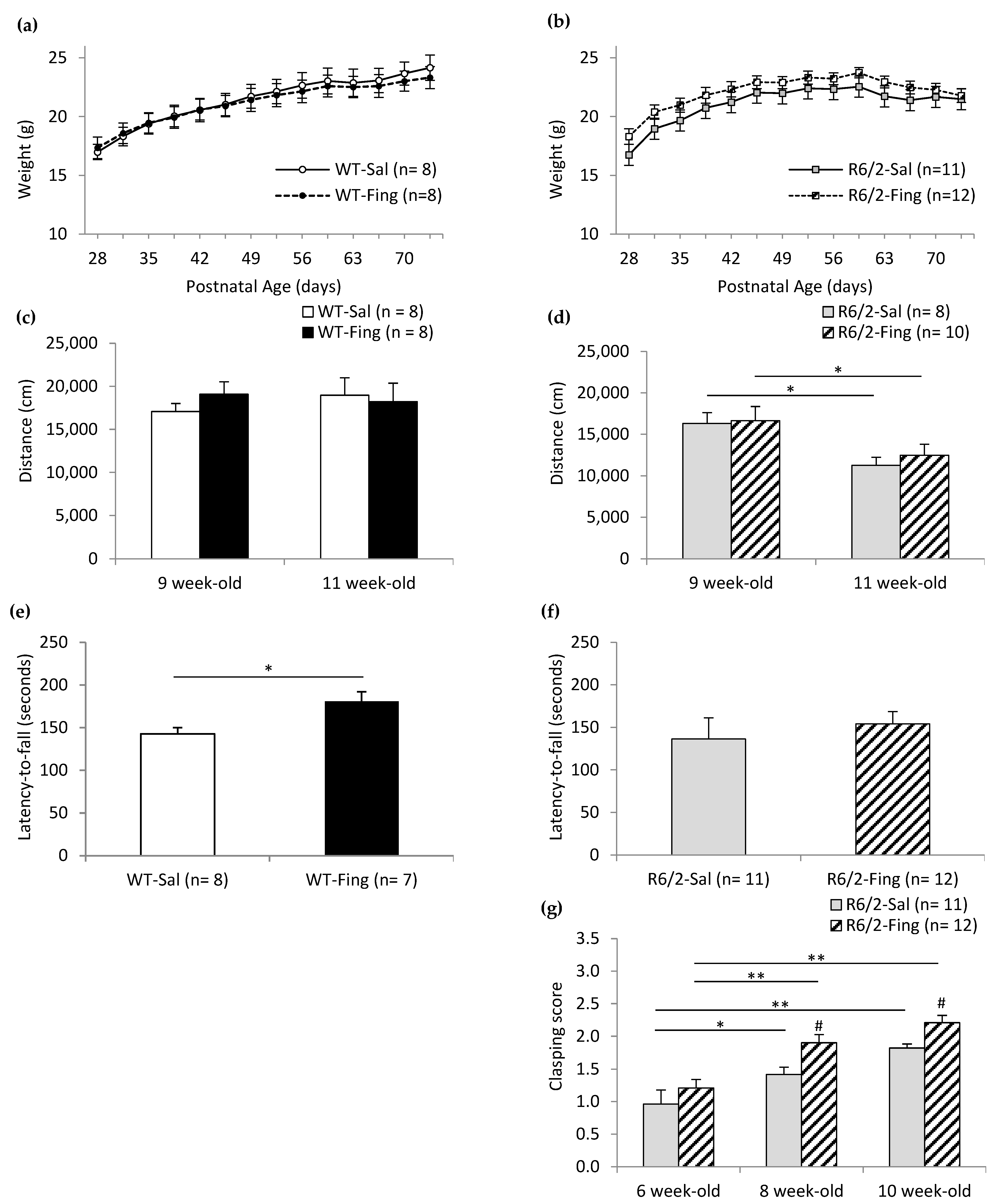

2.1. Effects of Chronic Fingolimod on Motor Behavior in WT and R6/2 Mice

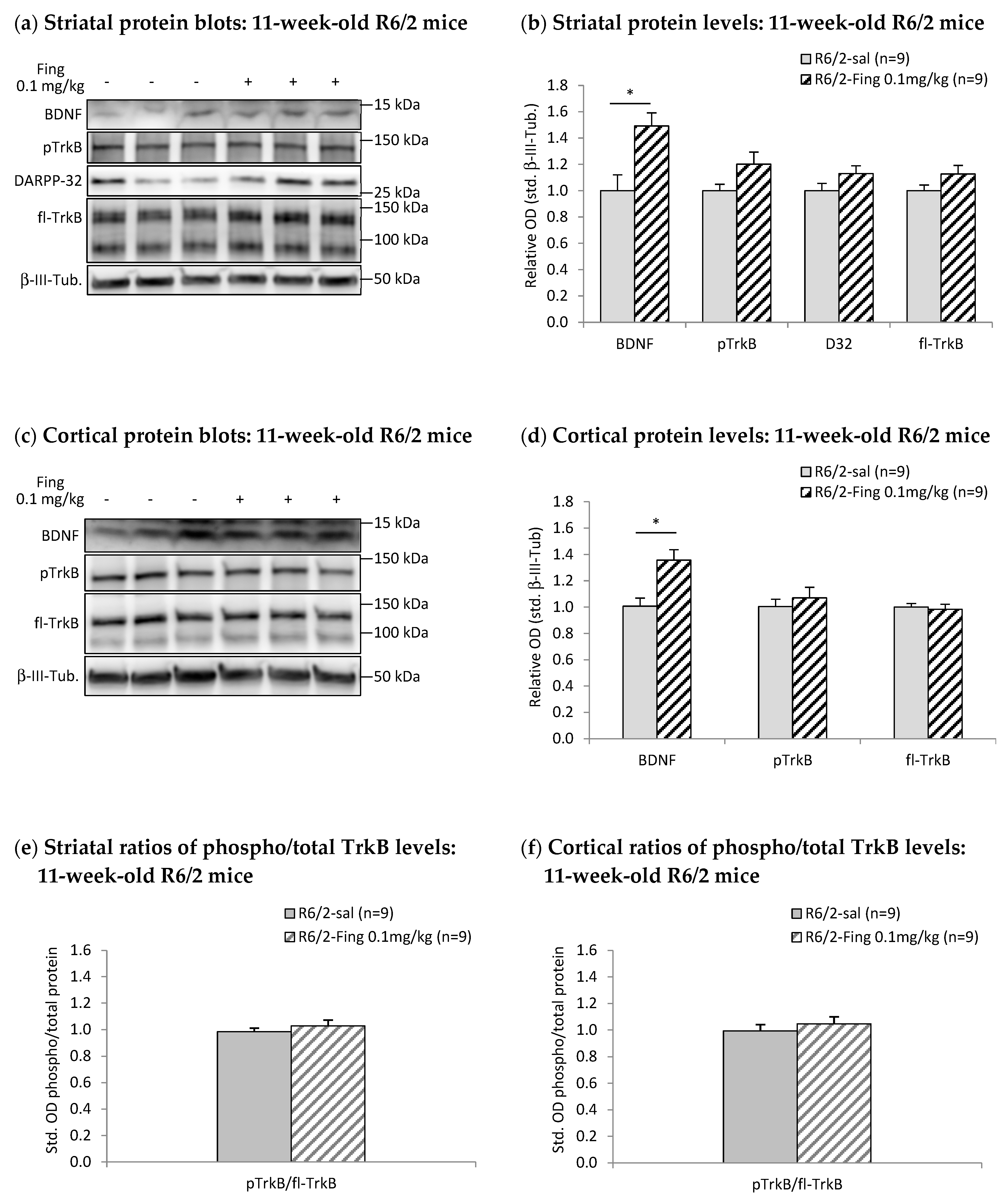

2.2. Effects of Chronic Fingolimod on BDNF-TrkB Signaling in Forebrain Motor Regions of R6/2 Mice

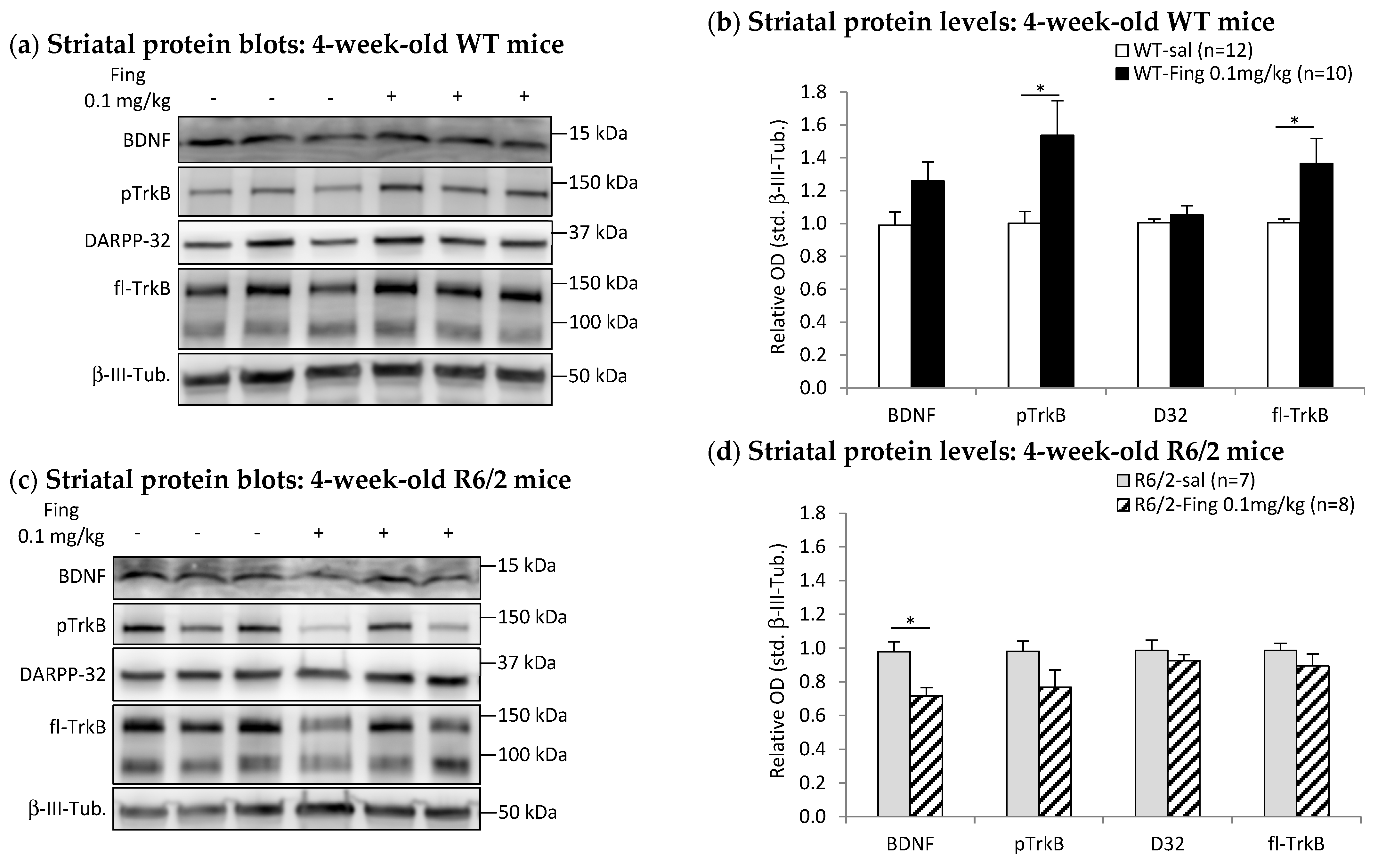

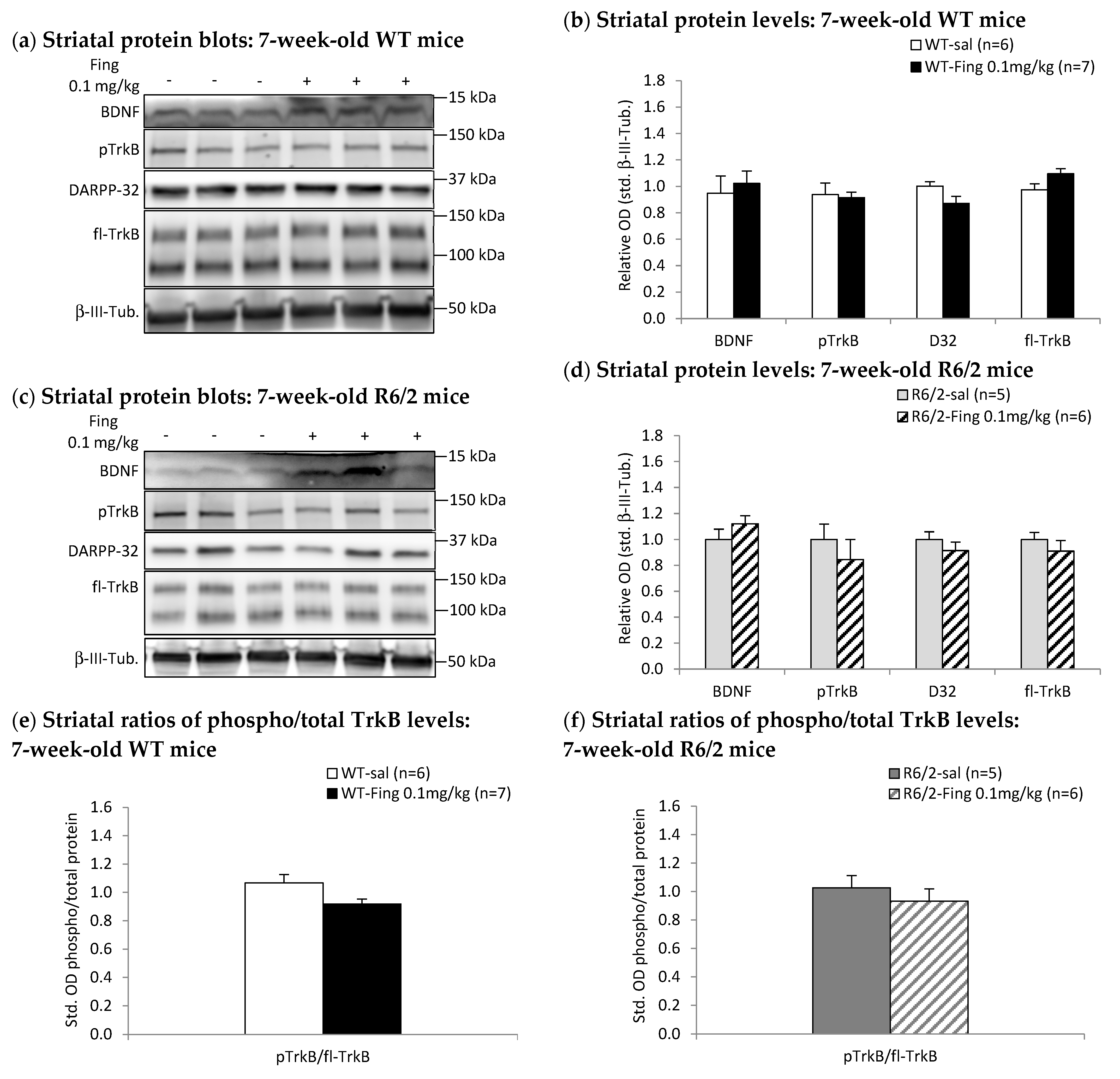

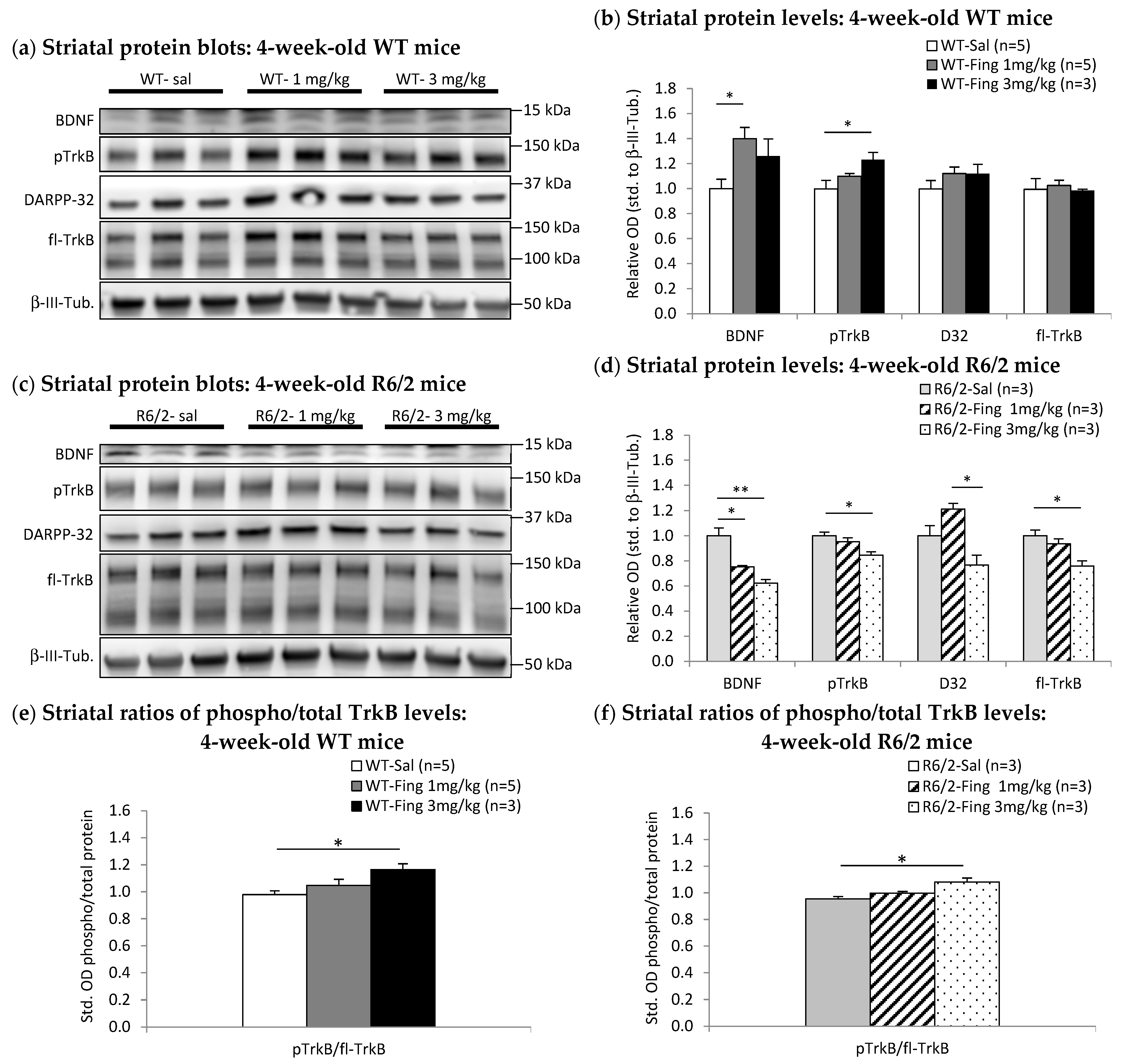

2.3. Acute Effects of Fingolimod on BDNF-TrkB Signaling in Presymptomatic and Symptomatic R6/2 Mice

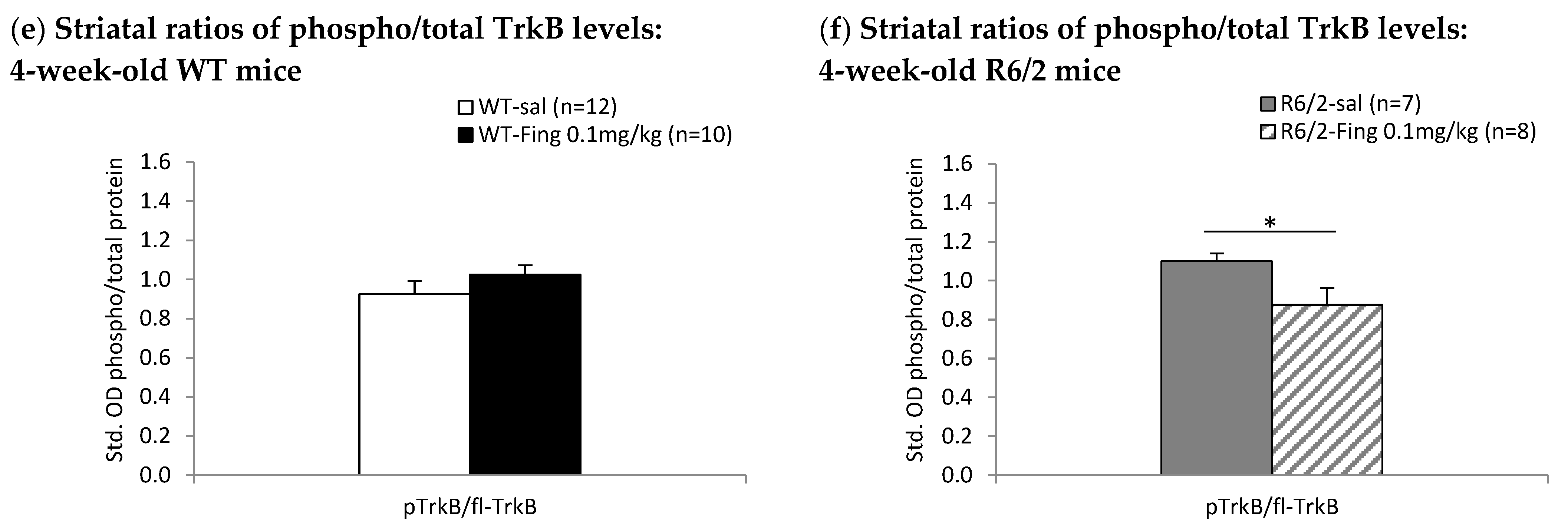

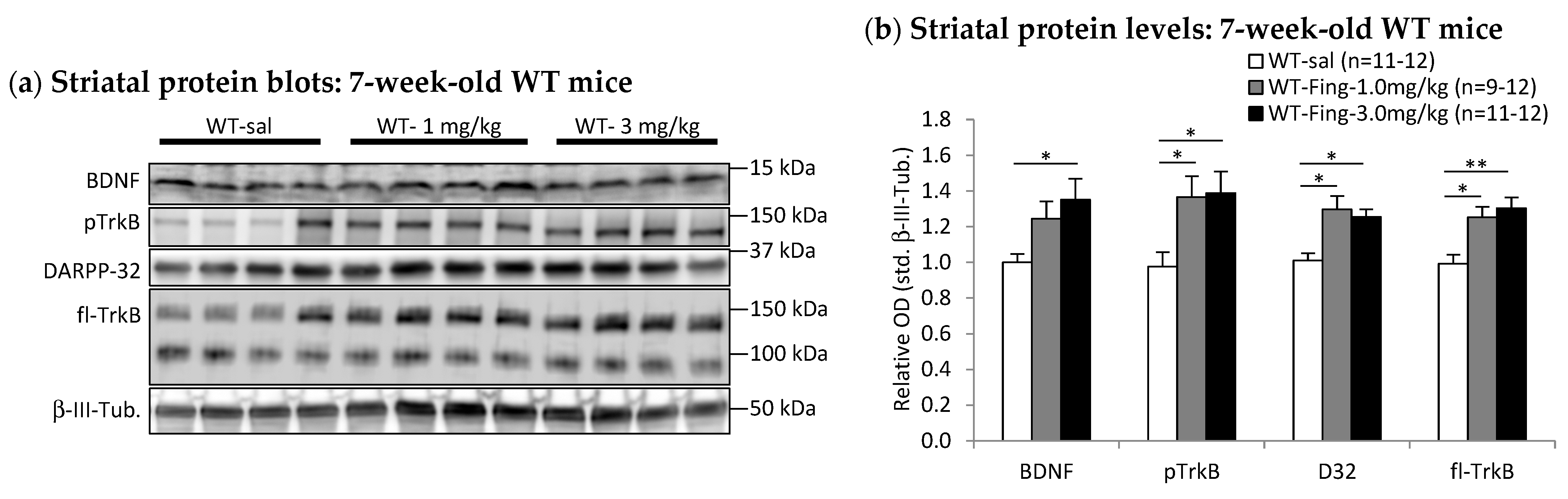

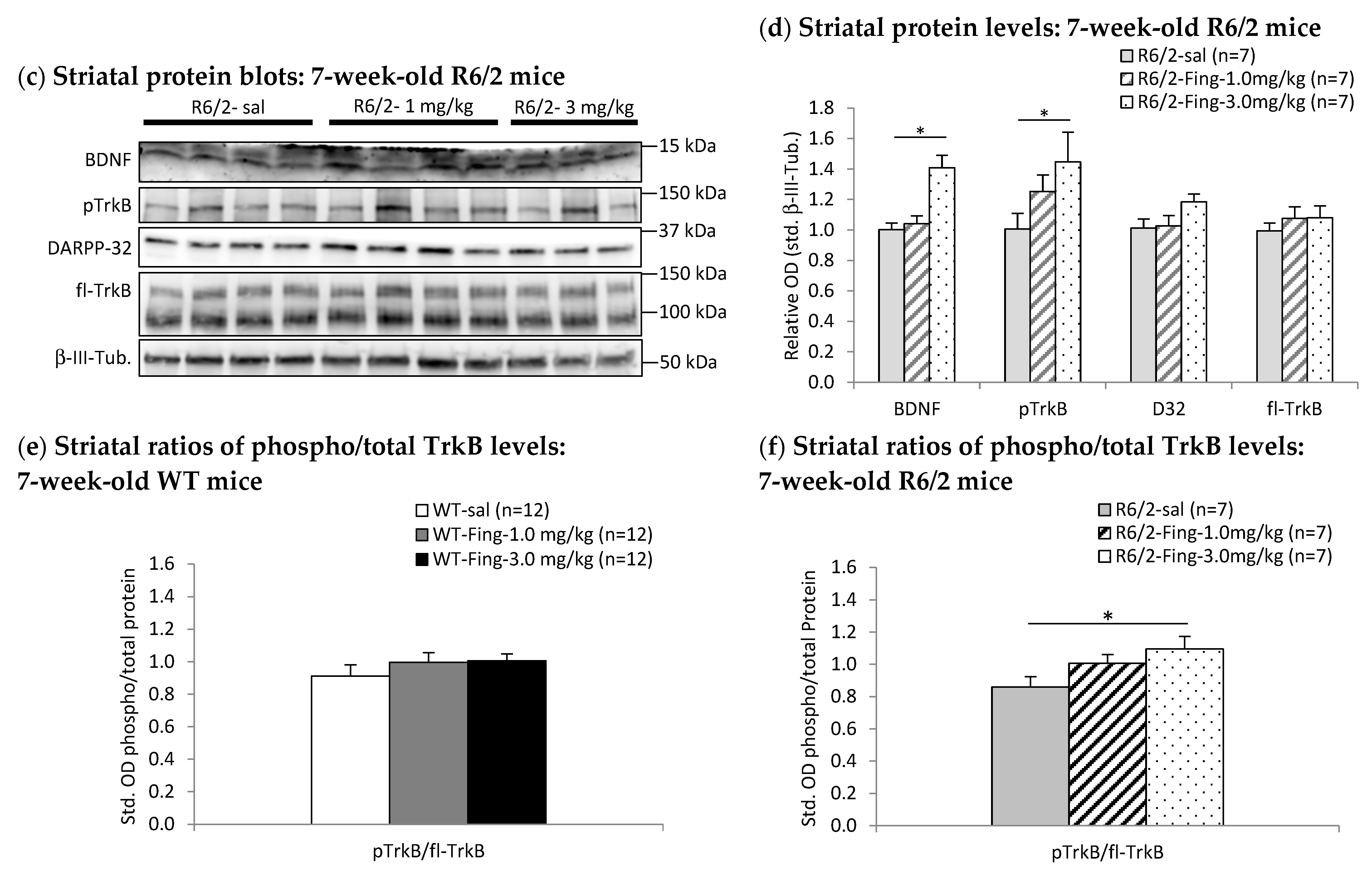

2.4. Fingolimod Dose Effect on BDNF-TrkB Signaling Proteins in Striatum of WT and R6/2 Mice

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Drug Treatment

4.3. Tissue Preparation and Western Blot Assays

4.4. Evaluation of Motor Behavior

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| AMPA | α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid |

| HD | Huntington’s disease |

References

- Albin, R.L.; Young, A.B.; Penney, J.B. The functional anatomy of basal ganglia disorders. Trends Neurosci. 1989, 12, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, A.; Hazrati, L.-N. Functional anatomy of the basal ganglia. I. The cortico-basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical loop. Brain Res. Rev. 1995, 20, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolam, J.P.; Hanley, J.J.; Booth, P.A.; Bevan, M.D. Synaptic organisation of the basal ganglia. J. Anat. 2000, 196, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baydyuk, M.; Russell, T.; Liao, G.-Y.; Zang, K.; An, J.J.; Reichardt, L.F.; Xu, B. TrkB receptor controls striatal formation by regulating the number of newborn striatal neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 1669–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baydyuk, M.; Xie, Y.; Tessarollo, L.; Xu, B. Midbrain-derived neurotrophins support survival of immature striatal projection neurons. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 3363–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivkovic, S.; Polonskaia, O.; Fariñas, I.; Ehrlich, M.E. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor regulates maturation of the DARPP-32 phenotype in striatal medium spiny neurons: Studies in vivo and in vitro. Neuroscience 1997, 79, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivkovic, S.; Ehrlich, M.E. Expression of the Striatal DARPP-32/ARPP-21 Phenotype in GABAergic Neurons Requires Neurotrophins In Vivo and In Vitro. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 5409–5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakao, N.; Brundin, P.; Funa, K.; Lindvall, O.; Odin, P. Trophic and protective actions of brain-derived neurotrophic factor on striatal DARPP-32-containing neurons in vitro. Dev. Brain Res. 1995, 90, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.-L.; Song, A.-H.; Wong, Y.-H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Poo, M.-M. Self-amplifying autocrine actions of BDNF in axon development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 18430–18435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Poo, M.-M. Neurotrophin regulation of neural circuit development and function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, J.R.; Costa, J.T.; Melo, C.V.; Felizzi, F.; Monteiro, P.; Pinto, M.J.; Inácio, A.R.; Wieloch, T.; Almeida, R.D.; Grãos, M.; et al. Excitotoxicity Downregulates TrkB.FL Signaling and Upregulates the Neuroprotective Truncated TrkB Receptors in Cultured Hippocampal and Striatal Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 4610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemelmans, A.P.; Horellou, P.; Pradier, L.; Brunet, I.; Colin, P.; Mallet, J. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor-mediated protection of striatal neurons in an excitotoxic rat model of Huntington’s disease, as demonstrated by adenoviral gene transfer. Hum. Gene Ther. 1999, 10, 2987–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibb, J.A.; Yan, Z.; Svenningsson, P.; Snyder, G.L.; Pieribone, V.A.; Horiuchi, A.; Nairn, A.C.; Messer, A.; Greengard, P. Severe deficiencies in dopamine signaling in presymptomatic Huntington’s disease mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 6809–6814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greengard, P.; Allen, P.B.; Nairn, A.C. Beyond the dopamine receptor: The DARPP-32/protein phosphatase-1 cascade. Neuron 1999, 23, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svenningsson, P.; Nishi, A.; Fisone, G.; Girault, J.A.; Nairn, A.C.; Greengard, P. DARPP-32: An integrator of neurotransmission. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2004, 44, 269–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biglan, K.M.; Ross, C.A.; Langbehn, D.R.; Aylward, E.H.; Stout, J.C.; Queller, S.; Carlozzi, N.E.; Duff, K.; Beglinger, L.J.; Paulsen, J.S. Motor abnormalities in premanifest persons with Huntington’s disease: The PREDICT-HD study. Mov. Disord. 2009, 24, 1763–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, J.; Long, J.; Johnson, H.; Aylward, E.; Ross, C.; Williams, J.; Nance, M.; Erwin, C.; Westervelt, H.; Harrington, D.; et al. Clinical and biomarker changes in premanifest Huntington disease show trial feasibility: A decade of the PREDICT-HD study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüb, U.; Seidel, K.; Heinsen, H.; Vonsattel, J.P.; den Dunnen, W.F.; Korf, H.W. Huntington’s disease (HD): The neuropathology of a multisystem neurodegenerative disorder of the human brain. Brain Pathol. 2016, 26, 726–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Huntington’s Disease Collaborative Research Group; MacDonald, M.E.; Ambrose, C.M.; Duyao, M.P.; Myers, R.H.; Lin, C.; Srinidhi, L.; Barnes, G.; Taylor, S.A.; James, M.; et al. A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington’s disease chromosomes. Cell 1993, 72, 971–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harjes, P.; Wanker, E.E. The hunt for huntingtin function: Interaction partners tell many different stories. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003, 28, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrell-Pages, M.; Zala, D.; Humbert, S.; Saudou, F. Huntington’s disease: From huntingtin function and dysfunction to therapeutic strategies. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2006, 63, 2642–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, L.R.; Charrin, B.C.; Borrell-Pagès, M.; Dompierre, J.P.; Rangone, H.; Cordelières, F.P.; De Mey, J.; MacDonald, M.E.; Leßmann, V.; Humbert, S.; et al. Huntingtin Controls Neurotrophic Support and Survival of Neurons by Enhancing BDNF Vesicular Transport along Microtubules. Cell 2004, 118, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuccato, C.; Cattaneo, E. Role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in Huntington’s disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 2007, 81, 294–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Li, C.H.; Chen, S.; Yoo, H.; Qin, X.; Park, H. Decreased BDNF Release in Cortical Neurons of a Knock-in Mouse Model of Huntington’s Disease. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhong, S.; Zhang, R.; Kang, K.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Zhao, M. Functional analysis of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in Huntington’s disease. Aging 2021, 13, 6103–6114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liot, G.; Zala, D.; Pla, P.; Mottet, G.; Piel, M.; Saudou, F. Mutant Huntingtin alters retrograde transport of TrkB receptors in striatal dendrites. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 6298–6309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.Q.; Rymar, V.V.; Sadikot, A.F. Impaired TrkB signaling underlies reduced BDNF-mediated trophic support of striatal neurons in the R6/2 mouse model of Huntington’s Disease. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabrizi, S.J.; Estevez-Fraga, C.; van Roon-Mom, W.M.C.; Flower, M.D.; Scahill, R.I.; Wild, E.J.; Muñoz-Sanjuan, I.; Sampaio, C.; Rosser, A.E.; Leavitt, B.R. Potential disease-modifying therapies for Huntington’s disease: Lessons learned and future opportunities. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, G.P.; Dorsey, R.; Gusella, J.F.; Hayden, M.R.; Kay, C.; Leavitt, B.R.; Nance, M.; Ross, C.A.; Scahill, R.I.; Wetzel, R.; et al. Huntington disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Mathur, A.G.; Pradhan, S.; Singh, D.B.; Gupta, S. Fingolimod (FTY720): First approved oral therapy for multiple sclerosis. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2011, 2, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, V.; Billich, A.; Baumruker, T.; Heining, P.; Schmouder, R.; Francis, G.; Aradhye, S.; Burtin, P. Fingolimod (FTY720): Discovery and development of an oral drug to treat multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 883–897, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deogracias, R.; Yazdani, M.; Dekkers, M.P.J.; Guy, J.; Ionescu, M.C.S.; Vogt, K.E.; Barde, Y.-A. Fingolimod, a sphingosine-1 phosphate receptor modulator, increases BDNF levels and improves symptoms of a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 14230–14235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukumoto, K.; Mizoguchi, H.; Takeuchi, H.; Horiuchi, H.; Kawanokuchi, J.; Jin, S.; Mizuno, T.; Suzumura, A. Fingolimod increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels and ameliorates amyloid β-induced memory impairment. Behav. Brain Res. 2014, 268, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Medrano, J.; Krishnamachari, S.; Villanueva, E.; Godfrey, W.H.; Lou, H.; Chinnasamy, R.; Arterburn, J.B.; Perez, R.G. Novel FTY720-Based Compounds Stimulate Neurotrophin Expression and Phosphatase Activity in Dopaminergic Cells. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pardo, A.; Amico, E.; Favellato, M.; Castrataro, R.; Fucile, S.; Squitieri, F.; Maglione, V. FTY720 (fingolimod) is a neuroprotective and disease-modifying agent in cellular and mouse models of Huntington disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 2251–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Han, M.; Wei, X.; Guo, Y.; Shi, H.; Zhang, X.; Perez, R.G.; Lou, H. FTY720 Attenuates 6-OHDA-Associated Dopaminergic Degeneration in Cellular and Mouse Parkinsonian Models. Neurochem. Res. 2017, 42, 686–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, A.; Kihara, Y.; Chun, J. Fingolimod: Direct CNS effects of sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor modulation and implications in multiple sclerosis therapy. J. Neurol. Sci. 2013, 328, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, H.; Takeuchi, H.; Mizuno, T.; Suzumura, A. Fingolimod phosphate promotes the neuroprotective effects of microglia. J. Neuroimmunol. 2013, 256, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.F.; Bowen, J.D.; Reder, A.T. The Direct Effects of Fingolimod in the Central Nervous System: Implications for Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis. CNS Drugs 2016, 30, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajimoto, T.; Okada, T.; Yu, H.; Goparaju, S.K.; Jahangeer, S.; Nakamura, S.-i. Involvement of Sphingosine-1-Phosphate in Glutamate Secretion in Hippocampal Neurons. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007, 27, 3429–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanno, T.; Nishizaki, T.; Proia, R.L.; Kajimoto, T.; Jahangeer, S.; Okada, T.; Nakamura, S. Regulation of synaptic strength by sphingosine 1-phosphate in the hippocampus. Neuroscience 2010, 171, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, E.; Cutler, R.G.; Flannery, R.; Wang, Y.; Mattson, M.P. Plasma membrane sphingomyelin hydrolysis increases hippocampal neuron excitability by sphingosine-1-phosphate mediated mechanisms. J. Neurochem. 2010, 114, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darios, F.D.; Jorgacevski, J.; Flašker, A.; Zorec, R.; García-Martinez, V.; Villanueva, J.; Gutiérrez, L.M.; Leese, C.; Bal, M.; Nosyreva, E.; et al. Sphingomimetic multiple sclerosis drug FTY720 activates vesicular synaptobrevin and augments neuroendocrine secretion. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, M.L.; Thangada, S.; Wu, M.-T.; Liu, C.H.; Macdonald, T.L.; Lynch, K.R.; Lin, C.-Y.; Hla, T. Immunosuppressive and Anti-angiogenic Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptor-1 Agonists Induce Ubiquitinylation and Proteasomal Degradation of the Receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 9082–9089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sykes, D.A.; Riddy, D.M.; Stamp, C.; Bradley, M.E.; McGuiness, N.; Sattikar, A.; Guerini, D.; Rodrigues, I.; Glaenzel, A.; Dowling, M.R.; et al. Investigating the molecular mechanisms through which FTY720-P causes persistent S1P1 receptor internalization. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 4797–4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Li, J.-N.; Kays, J.; Guerrero, M.; Nicol, G.D. Sphingosine 1-phosphate enhances the excitability of rat sensory neurons through activation of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors 1 and/or 3. J. Neuroinflamm. 2015, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, H. Could fingolimod provide cognitive benefits in patients with Huntington disease? Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015, 11, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascuñana, P.; Möhle, L.; Brackhan, M.; Pahnke, J. Fingolimod as a Treatment in Neurologic Disorders Beyond Multiple Sclerosis. Drugs RD 2020, 20, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deogracias, R.; Klein, C.; Matsumoto, T.; Yazdani, M.; Bibel, M.; Barde, Y.; Schubart, A. Expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor is regulated by fingolimod (FTY720) in cultured neurons. Mult. Scler. J. 2008, 14, 29–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangiarini, L.; Sathasivam, K.; Seller, M.; Cozens, B.; Harper, A.; Hetherington, C.; Lawton, M.; Trottier, Y.; Lehrach, H.; Davies, S.W.; et al. Exon 1 of the HD Gene with an Expanded CAG Repeat Is Sufficient to Cause a Progressive Neurological Phenotype in Transgenic Mice. Cell 1996, 87, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, E.C.; Kubilus, J.K.; Smith, K.; Cormier, K.; Signore, S.J.D.; Guelin, E.; Ryu, H.; Hersch, S.M.; Ferrante, R.J. Chronology of behavioral symptoms and neuropathological sequela in R6/2 Huntington’s disease transgenic mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 2005, 490, 354–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadi, P.; Boutet, A.; Rymar, V.V.; Rawal, K.; Maheux, J.; Kvann, J.C.; Tomaszewski, M.; Beaubien, F.; Cloutier, J.F.; Levesque, D.; et al. Relationship between BDNF expression in major striatal afferents, striatum morphology and motor behavior in the R6/2 mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Genes Brain Behav. 2013, 12, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuccato, C.; Liber, D.; Ramos, C.; Tarditi, A.; Rigamonti, D.; Tartari, M.; Valenza, M.; Cattaneo, E. Progressive loss of BDNF in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease and rescue by BDNF delivery. Pharmacol. Res. 2005, 52, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginés, S.; Paoletti, P.; Alberch, J. Impaired TrkB-mediated ERK1/2 Activation in Huntington Disease Knock-in Striatal Cells Involves Reduced p52/p46 Shc Expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 21537–21548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, D.A.; Belichenko, N.P.; Yang, T.; Condon, C.; Monbureau, M.; Shamloo, M.; Jing, D.; Massa, S.M.; Longo, F.M. A small molecule TrkB ligand reduces motor impairment and neuropathology in R6/2 and BACHD mouse models of Huntington’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 18712–18727, Erratum in: J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Burg, J.M.M.; Bacos, K.; Wood, N.I.; Lindqvist, A.; Wierup, N.; Woodman, B.; Wamsteeker, J.I.; Smith, R.; Deierborg, T.; Kuhar, M.J.; et al. Increased metabolism in the R6/2 mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2008, 29, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, D.M.; Alaghband, Y.; Hickey, M.A.; Joshi, P.R.; Hong, S.C.; Zhu, C.; Ando, T.K.; André, V.M.; Cepeda, C.; Watson, J.B.; et al. A critical window of CAG repeat-length correlates with phenotype severity in the R6/2 mouse model of Huntington’s disease. J. Neurophysiol. 2012, 107, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker-Krail, D.; Farrand, A.Q.; Boger, H.A.; Lavin, A. Effects of fingolimod administration in a genetic model of cognitive deficits. J. Neurosci. Res. 2016, 95, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhya, V.K.; Raju, R.; Verma, R.; Advani, J.; Sharma, R.; Radhakrishnan, A.; Nanjappa, V.; Narayana, J.; Somani, B.L.; Mukherjee, K.K.; et al. A network map of BDNF/TRKB and BDNF/p75NTR signaling system. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2013, 7, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yui, D.; Luikart, B.W.; McKay, R.M.; Li, Y.; Rubenstein, J.L.; Parada, L.F. Conditional ablation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor-TrkB signaling impairs striatal neuron development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 15491–15496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menalled, L.; El-Khodor, B.F.; Patry, M.; Suárez-Fariñas, M.; Orenstein, S.J.; Zahasky, B.; Leahy, C.; Wheeler, V.; Yang, X.W.; MacDonald, M.; et al. Systematic behavioral evaluation of Huntington’s disease transgenic and knock-in mouse models. Neurobiol. Dis. 2009, 35, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M.P.; Raymond, L.A. Chapter 17—Huntington disease. In Neurobiology of Brain Disorders, 2nd ed.; Zigmond, M.J., Wiley, C.A., Chesselet, M.-F., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 275–292. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich, M.E. Huntington’s disease and the striatal medium spiny neuron: Cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous mechanisms of disease. Neurotherapeutics 2012, 9, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.A.; Aylward, E.H.; Wild, E.J.; Langbehn, D.R.; Long, J.D.; Warner, J.H.; Scahill, R.I.; Leavitt, B.R.; Stout, J.C.; Paulsen, J.S.; et al. Huntington disease: Natural history, biomarkers and prospects for therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2014, 10, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.S.; Klapstein, G.J.; Koppel, A.; Gruen, E.; Cepeda, C.; Vargas, M.E.; Jokel, E.S.; Carpenter, E.M.; Zanjani, H.; Hurst, R.S.; et al. Enhanced sensitivity to N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor activation in transgenic and knockin mouse models of Huntington’s disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 1999, 58, 515–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda, C.; Ariano, M.A.; Calvert, C.R.; Flores-Hernández, J.; Chandler, S.H.; Leavitt, B.R.; Hayden, M.R.; Levine, M.S. NMDA receptor function in mouse models of Huntington disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 2001, 66, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaaro-Peled, H.; Kumar, S.; Hughes, D.; Sumitomo, A.; Kim, S.-H.; Zoubovsky, S.; Hirota-Tsuyada, Y.; Zala, D.; Bruyere, J.; Katz, B.M.; et al. Regulation of sensorimotor gating via Disc1/Huntingtin-mediated Bdnf transport in the cortico-striatal circuit. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 1805–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuccato, C.; Marullo, M.; Conforti, P.; MacDonald, M.E.; Tartari, M.; Cattaneo, E. Systematic Assessment of BDNF and Its Receptor Levels in Human Cortices Affected by Huntington’s Disease. Brain Pathol. 2008, 18, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speidell, A.; Bin Abid, N.; Yano, H. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Dysregulation as an Essential Pathological Feature in Huntington’s Disease: Mechanisms and Potential Therapeutics. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huwiler, A.; Zangemeister-Wittke, U. The sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator fingolimod as a therapeutic agent: Recent findings and new perspectives. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 185, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hla, T.; Brinkmann, V. Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P). Neurology 2011, 76, S3–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, S.; Mauri, L.; Prioni, S.; Cabitta, L.; Sonnino, S.; Prinetti, A.; Giussani, P. Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptors and Metabolic Enzymes as Druggable Targets for Brain Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.H.; Fehrenbacher, J.C.; Vasko, M.R.; Nicol, G.D. Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Via Activation of a G-Protein-Coupled Receptor(s) Enhances the Excitability of Rat Sensory Neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 2006, 96, 1042–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, T.; Kajimoto, T.; Jahangeer, S.; Nakamura, S.-i. Sphingosine kinase/sphingosine 1-phosphate signalling in central nervous system. Cell. Signal. 2009, 21, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riganti, L.; Antonucci, F.; Gabrielli, M.; Prada, I.; Giussani, P.; Viani, P.; Valtorta, F.; Menna, E.; Matteoli, M.; Verderio, C. Sphingosine-1-Phosphate (S1P) Impacts Presynaptic Functions by Regulating Synapsin I Localization in the Presynaptic Compartment. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiadou, S.; Knöll, B. The multiple sclerosis drug fingolimod (FTY720) stimulates neuronal gene expression, axonal growth and regeneration. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 279, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, Y.; Takeuchi, H.; Horiuchi, H.; Hanyu, T.; Kawanokuchi, J.; Jin, S.; Parajuli, B.; Sonobe, Y.; Mizuno, T.; Suzumura, A. Fingolimod Phosphate Attenuates Oligomeric Amyloid β–Induced Neurotoxicity via Increased Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Expression in Neurons. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafson, E.L.; Ehrlich, M.E.; Trivedi, P.; Greengard, P. Developmental regulation of phosphoprotein gene expression in the caudate-putamen of rat: An in situ hybridization study. Neuroscience 1992, 51, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunkhorst, R.; Vutukuri, R.; Pfeilschifter, W. Fingolimod for the treatment of neurological diseases—State of play and future perspectives. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stearns, N.A.; Schaevitz, L.R.; Bowling, H.; Nag, N.; Berger, U.V.; Berger-Sweeney, J. Behavioral and anatomical abnormalities in Mecp2 mutant mice: A model for Rett syndrome. Neuroscience 2007, 146, 907–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crevier-Sorbo, G.; Rymar, V.V.; Crevier-Sorbo, R.; Sadikot, A.F. Thalamostriatal degeneration contributes to dystonia and cholinergic interneuron dysfunction in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2020, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Q.; Khare, G.; Dani, V.; Nelson, S.; Jaenisch, R. The Disease Progression of Mecp2 Mutant Mice Is Affected by the Level of BDNF Expression. Neuron 2006, 49, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dani, V.S.; Chang, Q.; Maffei, A.; Turrigiano, G.G.; Jaenisch, R.; Nelson, S.B. Reduced cortical activity due to a shift in the balance between excitation and inhibition in a mouse model of Rett Syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 12560–12565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrens, P.F.; Franz, P.; Woodman, B.; Lindenberg, K.S.; Landwehrmeyer, G.B. Impaired glutamate transport and glutamate–glutamine cycling: Downstream effects of the Huntington mutation. Brain 2002, 125, 1908–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liévens, J.-C.; Woodman, B.; Mahal, A.; Bates, G.P. Abnormal Phosphorylation of Synapsin I Predicts a Neuronal Transmission Impairment in the R6/2 Huntington’s Disease Transgenic Mice. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2002, 20, 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda, C.; Hurst, R.S.; Calvert, C.R.; Hernandez-Echeagaray, E.; Nguyen, O.K.; Jocoy, E.; Christian, L.J.; Ariano, M.A.; Levine, M.S. Transient and Progressive Electrophysiological Alterations in the Corticostriatal Pathway in a Mouse Model of Huntington’s Disease. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.J.; Levine, M.S. Changes in expression of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits occur early in the R6/2 mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Dev. Neurosci. 2006, 28, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traficante, A.; Riozzi, B.; Cannella, M.; Rampello, L.; Squitieri, F.; Battaglia, G. Reduced activity of cortico-striatal fibres in the R6/2 mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Neuroreport 2007, 18, 1997–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda, C.; Starling, A.J.; Wu, N.; Nguyen, O.K.; Uzgil, B.; Soda, T.; André, V.M.; Ariano, M.A.; Levine, M.S. Increased GABAergic function in mouse models of Huntington’s disease: Reversal by BDNF. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004, 78, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milnerwood, A.J.; Raymond, L.A. Early synaptic pathophysiology in neurodegeneration: Insights from Huntington’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 2010, 33, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besusso, D.; Geibel, M.; Kramer, D.; Schneider, T.; Pendolino, V.; Picconi, B.; Calabresi, P.; Bannerman, D.M.; Minichiello, L. BDNF–TrkB signaling in striatopallidal neurons controls inhibition of locomotor behavior. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, A.; Spiombi, E.; Frasca, A.; Landsberger, N.; Zagrebelsky, M.; Korte, M. Fingolimod Modulates Dendritic Architecture in a BDNF-Dependent Manner. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, A.E.; Griffith, E.C.; Greenberg, M.E. Regulation of transcription factors by neuronal activity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, A.E.; Pruunsild, P.; Timmusk, T. Neurotrophins: Transcription and translation. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2014, 220, 67–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donegà, S.; Tongiorgi, E. Detecting BDNF Protein Forms by ELISA, Western Blot, and Immunofluorescence. In Neuromethods; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Komnig, D.; Dagli, T.C.; Habib, P.; Zeyen, T.; Schulz, J.B.; Falkenburger, B.H. Fingolimod (FTY720) is not protective in the subacute MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease and does not lead to a sustainable increase of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J. Neurochem. 2018, 147, 678–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kartalou, G.-I.; Pereira, A.R.S.; Endres, T.; Lesnikova, A.; Casarotto, P.; Pousinha, P.; Delanoe, K.; Edelmann, E.; Castrén, E.; Gottmann, K.; et al. Anti-inflammatory treatment with FTY720 starting after onset of symptoms reverses synaptic and memory deficits in an AD mouse model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.A.; Schmid, C.; Zurbruegg, S.; Jivkov, M.; Doelemeyer, A.; Theil, D.; Dubost, V.; Beckmann, N. Fingolimod inhibits brain atrophy and promotes brain-derived neurotrophic factor in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroimmunol. 2018, 318, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hait, N.C.; Wise, L.E.; Allegood, J.C.; O’Brien, M.; Avni, D.; Reeves, T.M.; Knapp, P.E.; Lu, J.; Luo, C.; Miles, M.F.; et al. Active, phosphorylated fingolimod inhibits histone deacetylases and facilitates fear extinction memory. Nat. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 971–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Ulate, I.; Yang, B.; Vargas-Medrano, J.; Perez, R.G. FTY720 (Fingolimod) reverses alpha-synuclein-induced downregulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA in OLN-93 oligodendroglial cells. Neuropharmacology 2017, 117, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizugishi, K.; Yamashita, T.; Olivera, A.; Miller, G.F.; Spiegel, S.; Proia, R.L. Essential role for sphingosine kinases in neural and vascular development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 11113–11121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Santos-Garcia, I.; Eiriz, I.; Bruning, T.; Kvasnicka, A.; Friedecky, D.; Nyman, T.A.; Pahnke, J. Sex-dependent efficacy of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonist FTY720 in mitigating Huntington’s disease. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 211, 107557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguez, A.; García-Díaz Barriga, G.; Brito, V.; Straccia, M.; Giralt, A.; Ginés, S.; Canals, J.M.; Alberch, J. Fingolimod (FTY720) enhances hippocampal synaptic plasticity and memory in Huntington’s disease by preventing p75NTR up-regulation and astrocyte-mediated inflammation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, 4958–4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pardo, A.; Pepe, G.; Castaldo, S.; Marracino, F.; Capocci, L.; Amico, E.; Madonna, M.; Giova, S.; Jeong, S.K.; Park, B.-M.; et al. Stimulation of Sphingosine Kinase 1 (SPHK1) Is Beneficial in a Huntington’s Disease Pre-clinical Model. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthi-Carter, R.; Apostol, B.L.; Dunah, A.W.; DeJohn, M.M.; Farrell, L.A.; Bates, G.P.; Young, A.B.; Standaert, D.G.; Thompson, L.M.; Cha, J.-H.J. Complex alteration of NMDA receptors in transgenic Huntington’s disease mouse brain: Analysis of mRNA and protein expression, plasma membrane association, interacting proteins, and phosphorylation. Neurobiol. Dis. 2003, 14, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- André, V.M.; Cepeda, C.; Venegas, A.; Gomez, Y.; Levine, M.S. Altered Cortical Glutamate Receptor Function in the R6/2 Model of Huntington’s Disease. J. Neurophysiol. 2006, 95, 2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabel, C.; Mao, L.; Woodman, B.; Rohe, M.; Wacker, M.A.; Klare, Y.; Koppelstatter, A.; Nebrich, G.; Klein, O.; Grams, S.; et al. A large number of protein expression changes occur early in life and precede phenotype onset in a mouse model for huntington disease. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2009, 8, 720–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.H.; Kosinski, C.M.; Kerner, J.A.; Alsdorf, S.A.; Mangiarini, L.; Davies, S.W.; Penney, J.B.; Bates, G.P.; Young, A.B. Altered brain neurotransmitter receptors in transgenic mice expressing a portion of an abnormal human huntington disease gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 6480–6485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milnerwood, A.J.; Gladding, C.M.; Pouladi, M.A.; Kaufman, A.M.; Hines, R.M.; Boyd, J.D.; Ko, R.W.Y.; Vasuta, O.C.; Graham, R.K.; Hayden, M.R.; et al. Early Increase in Extrasynaptic NMDA Receptor Signaling and Expression Contributes to Phenotype Onset in Huntington’s Disease Mice. Neuron 2010, 65, 178–190, Correction in: Neuron 2010, 65, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, M.P.; Raymond, L.A. Extrasynaptic NMDA Receptor Involvement in Central Nervous System Disorders. Neuron 2014, 82, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardingham, G.E.; Bading, H. Synaptic versus extrasynaptic NMDA receptor signalling: Implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 682–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardingham, G.E.; Fukunaga, Y.; Bading, H. Extrasynaptic NMDARs oppose synaptic NMDARs by triggering CREB shut-off and cell death pathways. Nat. Neurosci. 2002, 5, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léveillé, F.; El Gaamouch, F.; Gouix, E.; Lecocq, M.; Lobner, D.; Nicole, O.; Buisson, A. Neuronal viability is controlled by a functional relation between synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 4258–4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.M.; Huganir, R.L. MAPK cascade signalling and synaptic plasticity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, D.M.; André, V.M.; Uzgil, B.O.; Gee, S.M.; Fisher, Y.E.; Cepeda, C.; Levine, M.S. Alterations in Cortical Excitation and Inhibition in Genetic Mouse Models of Huntington’s Disease. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 10371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, L.A.; André, V.M.; Cepeda, C.; Gladding, C.M.; Milnerwood, A.J.; Levine, M.S. Pathophysiology of Huntington’s disease: Time-dependent alterations in synaptic and receptor function. Neuroscience 2011, 198, 252–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wild, E.; Björkqvist, M.; Tabrizi, S.J. Immune markers for Huntington’s disease? Expert Rev. Neurother. 2008, 8, 1779–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Li, S.; Li, X.-J.; Yin, D. Neuroinflammation in Huntington’s disease: From animal models to clinical therapeutics. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1088124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, H.-Y.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chen, H.-M.; Tu, P.-H.; Chern, Y. A critical role of astrocyte-mediated nuclear factor-κB-dependent inflammation in Huntington’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 1826–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pido-Lopez, J.; Andre, R.; Benjamin, A.C.; Ali, N.; Farag, S.; Tabrizi, S.J.; Bates, G.P. In vivo neutralization of the protagonist role of macrophages during the chronic inflammatory stage of Huntington’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasser, J.; Gillet, G.; Valadas, J.S.; Rouvière, L.; Kotian, A.; Fan, W.; Keaney, J.; Kadiu, I. Innate immune activation and aberrant function in the R6/2 mouse model and Huntington’s disease iPSC-derived microglia. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023, 16, 1191324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjorkqvist, M.; Wild, E.J.; Thiele, J.; Silvestroni, A.; Andre, R.; Lahiri, N.; Raibon, E.; Lee, R.V.; Benn, C.L.; Soulet, D.; et al. A novel pathogenic pathway of immune activation detectable before clinical onset in Huntington’s disease. J. Exp. Med. 2008, 205, 1869–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etxeberria-Rekalde, E.; Alzola-Aldamizetxebarria, S.; Flunkert, S.; Hable, I.; Daurer, M.; Neddens, J.; Hutter-Paier, B. Quantification of Huntington’s Disease Related Markers in the R6/2 Mouse Model. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 13, 617229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothhammer, V.; Kenison, J.E.; Tjon, E.; Takenaka, M.C.; de Lima, K.A.; Borucki, D.M.; Chao, C.-C.; Wilz, A.; Blain, M.; Healy, L.; et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulation suppresses pathogenic astrocyte activation and chronic progressive CNS inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 2012–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, S.D.; Nicole, O.; Peavy, R.D.; Montoya, L.M.; Lee, C.J.; Murphy, T.J.; Traynelis, S.F.; Hepler, J.R. Common Signaling Pathways Link Activation of Murine PAR-1, LPA, and S1P Receptors to Proliferation of Astrocytes. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003, 64, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullershausen, F.; Craveiro, L.M.; Shin, Y.; Cortes-Cros, M.; Bassilana, F.; Osinde, M.; Wishart, W.L.; Guerini, D.; Thallmair, M.; Schwab, M.E.; et al. Phosphorylated FTY720 promotes astrocyte migration through sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors. J. Neurochem. 2007, 102, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reick, C.; Ellrichmann, G.; Tsai, T.; Lee, D.-H.; Wiese, S.; Gold, R.; Saft, C.; Linker, R.A. Expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in astrocytes—Beneficial effects of glatiramer acetate in the R6/2 and YAC128 mouse models of Huntington’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 285, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pardo, A.; Amico, E.; Basit, A.; Armirotti, A.; Joshi, P.; Neely, D.M.; Vuono, R.; Castaldo, S.; Digilio, A.F.; Scalabrì, F.; et al. Defective Sphingosine-1-phosphate metabolism is a druggable target in Huntington’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5280, Erratum in Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirhaji, L.; Milani, P.; Dalin, S.; Wassie, B.T.; Dunn, D.E.; Fenster, R.J.; Avila-Pacheco, J.; Greengard, P.; Clish, C.B.; Heiman, M.; et al. Identifying therapeutic targets by combining transcriptional data with ordinal clinical measurements. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-González, X.; Cubo, E.; Simón-Vicente, L.; Mariscal, N.; Alcaraz, R.; Aguado, L.; Rivadeneyra-Posadas, J.; Sanz-Solas, A.; Saiz-Rodríguez, M. Pharmacogenetics in the Treatment of Huntington’s Disease: Review and Future Perspectives. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, Y.-H.; Chern, Y.; Yang, H.-T.; Chen, H.-M.; Lin, C.-J. Regulation of P-glycoprotein expression in brain capillaries in Huntington’s disease and its impact on brain availability of antipsychotic agents risperidone and paliperidone. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2016, 36, 1412–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.-C.; Lin, C.-J. The regulation of drug-metabolizing enzymes and membrane transporters by inflammation: Evidences in inflammatory diseases and age-related disorders. J. Food Drug Anal. 2019, 27, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L. Analyzing Gels and Western Blots with Imagej. Available online: https://lukemiller.org/index.php/2010/11/analyzing-gels-and-western-blots-with-image-j/ (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Bailoo, J.D.; Bohlen, M.O.; Wahlsten, D. The precision of video and photocell tracking systems and the elimination of tracking errors with infrared backlighting. J. Neurosci. Methods 2010, 188, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, R.J.; Lione, L.A.; Humby, T.; Mangiarini, L.; Mahal, A.; Bates, G.P.; Dunnett, S.B.; Morton, A.J. Characterization of Progressive Motor Deficits in Mice Transgenic for the Human Huntington’s Disease Mutation. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 3248–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monville, C.; Torres, E.M.; Dunnett, S.B. Comparison of incremental and accelerating protocols of the rotarod test for the assessment of motor deficits in the 6-OHDA model. J. Neurosci. Methods 2006, 158, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nguyen, K.Q.; Rymar, V.V.; Sadikot, A.F. Fingolimod Effects on Motor Function and BDNF-TrkB Signaling in a Huntington’s Mouse Model Are Disease-Stage-Dependent. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010494

Nguyen KQ, Rymar VV, Sadikot AF. Fingolimod Effects on Motor Function and BDNF-TrkB Signaling in a Huntington’s Mouse Model Are Disease-Stage-Dependent. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):494. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010494

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Khanh Q., Vladimir V. Rymar, and Abbas F. Sadikot. 2026. "Fingolimod Effects on Motor Function and BDNF-TrkB Signaling in a Huntington’s Mouse Model Are Disease-Stage-Dependent" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010494

APA StyleNguyen, K. Q., Rymar, V. V., & Sadikot, A. F. (2026). Fingolimod Effects on Motor Function and BDNF-TrkB Signaling in a Huntington’s Mouse Model Are Disease-Stage-Dependent. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010494