Palmar Fascia Fibrosis in Dupuytren’s Disease: A Narrative Review of Pathogenic Mechanisms and Molecular Insights

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

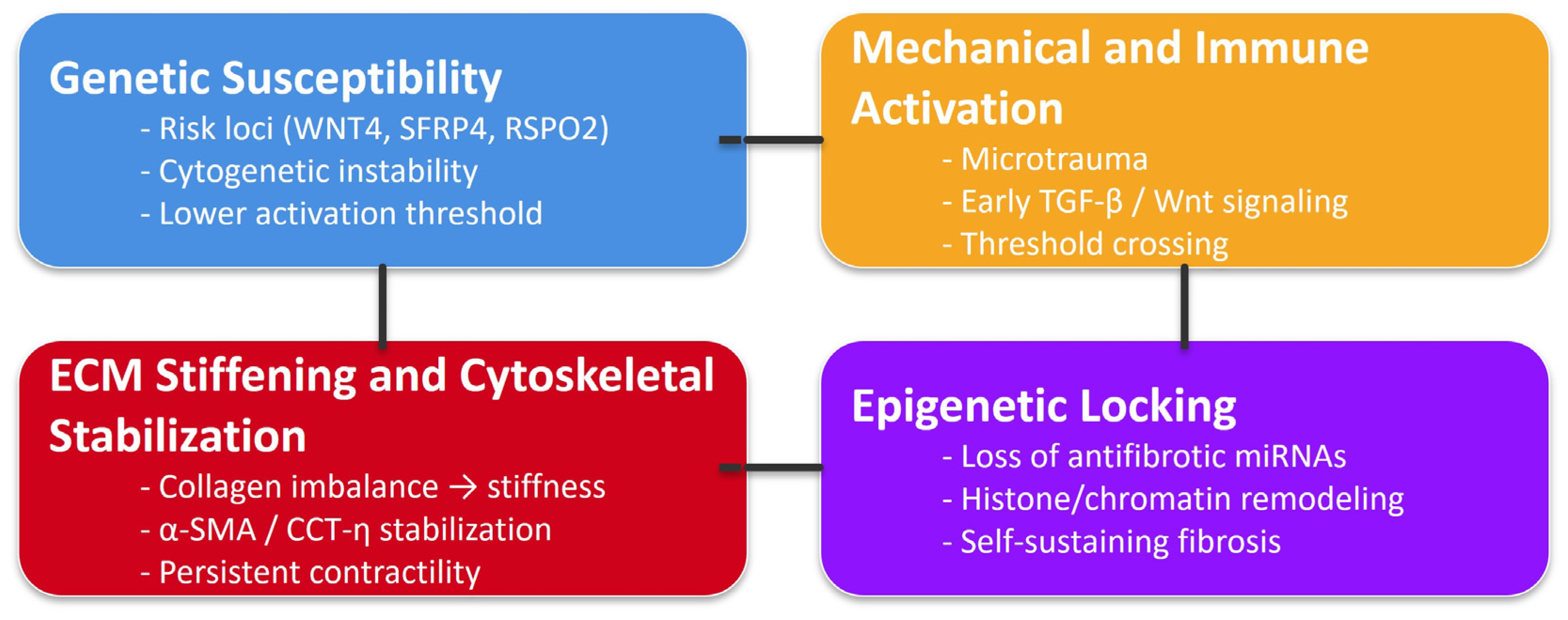

3. Genetic and Cytogenetic Contributions

4. Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Remodeling

5. Aberrant Cellular Signaling

Integrated TGF-β/Wnt/ECM Feedback Loop in Dupuytren’s Disease

6. Cytoskeletal Regulation and Contractility

7. Immune and Inflammatory Crosstalk

8. Growth Factors and Cytokine Profiles

9. Epigenetic and Molecular Modulators

10. Animal Models and Ex Vivo Systems

11. Discussion

Future Directions

12. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DD | Dupuytren’s disease |

| α-SMA | α-smooth muscle actin |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming growth factor-β1 |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

| PDGF | Platelet-derived growth factor |

| PAI-1 | Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 |

| IGF-2 | Insulin-like Growth Factor 2 |

| WT 1 | Wilms Tumor 1 |

| Wnt 4 | Wnt Family Member 4 |

| FAK | Focal adhesion kinase |

| ROCK | Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase |

References

- van Straalen, R.J.M.; de Boer, M.R.; Vos, F.; Werker, P.M.N.; Broekstra, D.C. The incidence and prevalence of Dupuytren’s disease in primary care: Results from a text mining approach on registration data. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care. 2025, 43, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gonga-Cavé, B.C.; Pena Diaz, A.M.; O’Gorman, D.B. Biomimetic analyses of interactions between macrophages and palmar fascia myofibroblasts derived from Dupuytren’s disease reveal distinct inflammatory cytokine responses. Wound Repair. Regen. 2021, 29, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopp, J.; Seyhan, H.; Müller, B.; Lanczak, J.; Pausch, E.; Gressner, A.M.; Dooley, S.; Horch, R.E. N-acetyl-L-cysteine abrogates fibrogenic properties of fibroblasts isolated from Dupuytren’s disease by blunting TGF-beta signalling. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2006, 10, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van der Slot, A.J.; Zuurmond, A.M.; van den Bogaerdt, A.J.; Ulrich, M.M.; Middelkoop, E.; Boers, W.; Karel Ronday, H.; DeGroot, J.; Huizinga, T.W.; Bank, R.A. Increased formation of pyridinoline cross-links due to higher telopeptide lysyl hydroxylase levels is a general fibrotic phenomenon. Matrix Biol. 2004, 23, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Tugade, T.; Sun, E.; Pena Diaz, A.M.; O’Gorman, D.B. Sustained AWT1 expression by Dupuytren’s disease myofibroblasts promotes a proinflammatory milieu. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 16, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Raykha, C.; Crawford, J.; Gan, B.S.; Fu, P.; Bach, L.A.; O’Gorman, D.B. IGF-II and IGFBP-6 regulate cellular contractility and proliferation in Dupuytren’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013, 1832, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten Dam, E.J.; van Beuge, M.M.; Bank, R.A.; Werker, P.M. Further evidence of the involvement of the Wnt signaling pathway in Dupuytren’s disease. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2016, 10, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ng, M.; Thakkar, D.; Southam, L.; Werker, P.; Ophoff, R.; Becker, K.; Nothnagel, M.; Franke, A.; Nürnberg, P.; Espirito-Santo, A.I.; et al. A Genome-wide Association Study of Dupuytren Disease Reveals 17 Additional Variants Implicated in Fibrosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 101, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Major, M.; Freund, M.K.; Burch, K.S.; Mancuso, N.; Ng, M.; Furniss, D.; Pasaniuc, B.; Ophoff, R.A. Integrative analysis of Dupuytren’s disease identifies novel risk locus and reveals a shared genetic etiology with BMI. Genet. Epidemiol. 2019, 43, 629–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Basile, G.; Bianco Prevot, L.; Ciccarelli, A.; Tronconi, L.P.; Bolcato, V. EN: Medico-legal evaluation of a claim for Dupuytren’s disease treatment: Indication for surgery based on best evidence. Clin. Ter. 2024, 175, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qureshi, F.I.; Hornigold, R.; Spencer, J.D.; Hall, S.M. Langerhans cells in Dupuytren’s contracture. J. Hand Surg. Br. 2001, 26, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobie, R.; West, C.C.; Henderson, B.E.P.; Wilson-Kanamori, J.R.; Markose, D.; Kitto, L.J.; Portman, J.R.; Beltran, M.; Sohrabi, S.; Akram, A.R.; et al. Deciphering Mesenchymal Drivers of Human Dupuytren’s Disease at Single-Cell Level. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 142, 114–123.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripković, I.; Ogorevc, M.; Vuković, D.; Saraga-Babić, M.; Mardešić, S. Fibrosis-Associated Signaling Molecules Are Differentially Expressed in Palmar Connective Tissues of Patients with Carpal Tunnel Syndrome and Dupuytren’s Disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bonnici, A.V.; Birjandi, F.; Spencer, J.D.; Fox, S.P.; Berry, A.C. Chromosomal abnormalities in Dupuytren’s contracture and carpal tunnel syndrome. J. Hand Surg. Br. 1992, 17, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michou, L.; Lermusiaux, J.L.; Teyssedou, J.P.; Bardin, T.; Beaudreuil, J.; Petit-Teixeira, E. Genetics of Dupuytren’s disease. Jt. Bone Spine 2012, 79, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarty, S.; Syed, F.; Bayat, A. Role of the HLA System in the Pathogenesis of Dupuytren’s Disease. Hand 2010, 5, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bayat, A.; Stanley, J.K.; Watson, J.S.; Ferguson, M.W.; Ollier, W.E. Genetic susceptibility to Dupuytren’s disease: Transforming growth factor beta receptor (TGFbetaR) gene polymorphisms and Dupuytren’s disease. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 2003, 56, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, S.; Krogsgaard, D.G.; Aagaard Larsen, L.; Iachina, M.; Skytthe, A.; Frederiksen, H. Genetic and environmental influences in Dupuytren’s disease: A study of 30,330 Danish twin pairs. J. Hand Surg. Eur. Vol. 2015, 40, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hu, F.Z.; Nystrom, A.; Ahmed, A.; Palmquist, M.; Dopico, R.; Mossberg, I.; Gladitz, J.; Rayner, M.; Post, J.C.; Ehrlich, G.D.; et al. Mapping of an autosomal dominant gene for Dupuytren’s contracture to chromosome 16q in a Swedish family. Clin. Genet. 2005, 68, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolmans, G.H.; Werker, P.M.; Hennies, H.C.; Furniss, D.; Festen, E.A.; Franke, L.; Becker, K.; van der Vlies, P.; Wolffenbuttel, B.H.; Tinschert, S.; et al. Wnt signaling and Dupuytren’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riesmeijer, S.A.; Kamali, Z.; Ng, M.; Drichel, D.; Piersma, B.; Becker, K.; Layton, T.B.; Nanchahal, J.; Nothnagel, M.; Vaez, A.; et al. A genome-wide association meta-analysis implicates Hedgehog and Notch signaling in Dupuytren’s disease. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tomasek, J.J.; Vaughan, M.B.; Haaksma, C.J. Cellular structure and biology of Dupuytren’s disease. Hand Clin. 1999, 15, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verjee, L.S.; Midwood, K.; Davidson, D.; Essex, D.; Sandison, A.; Nanchahal, J. Myofibroblast distribution in Dupuytren’s cords: Correlation with digital contracture. J. Hand Surg. Am. 2009, 34, 1785–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, J.C.; Varallo, V.M.; Ross, D.C.; Faber, K.J.; Roth, J.H.; Seney, S.; Gan, B.S. Wound healing-associated proteins Hsp47 and fibronectin are elevated in Dupuytren’s contracture. J. Surg. Res. 2004, 117, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vi, L.; Njarlangattil, A.; Wu, Y.; Gan, B.S.; O’Gorman, D.B. Type-1 Collagen differentially alters beta-catenin accumulation in primary Dupuytren’s Disease cord and adjacent palmar fascia cells. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2009, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ratajczak-Wielgomas, K.; Gosk, J.; Rabczyński, J.; Augoff, K.; Podhorska-Okołów, M.; Gamian, A.; Rutowski, R. Expression of MMP-2, TIMP-2, TGF-β1, and decorin in Dupuytren’s contracture. Connect. Tissue Res. 2012, 53, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satish, L.; LaFramboise, W.A.; O’Gorman, D.B.; Johnson, S.; Janto, B.; Gan, B.S.; Baratz, M.E.; Hu, F.Z.; Post, J.C.; Ehrlich, G.D.; et al. Identification of differentially expressed genes in fibroblasts derived from patients with Dupuytren’s Contracture. BMC Med. Genom. 2008, 1, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brickley-Parsons, D.; Glimcher, M.J.; Smith, R.J.; Albin, R.; Adams, J.P. Biochemical changes in the collagen of the palmar fascia in patients with Dupuytren’s disease. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1981, 63, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, P.; Chojnowski, A.J.; Davidson, R.K.; Riley, G.P.; Donell, S.T.; Clark, I.M. A complete expression profile of matrix-degrading metalloproteinases in Dupuytren’s disease. J. Hand Surg. Am. 2007, 32, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satish, L.; Gallo, P.H.; Baratz, M.E.; Johnson, S.; Kathju, S. Reversal of TGF-β1 stimulation of α-smooth muscle actin and extracellular matrix components by cyclic AMP in Dupuytren’s-derived fibroblasts. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2011, 12, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhao, W.; Li, Z.; Ma, S.; Chen, W.; Wan, Z.; Zhu, L.; Li, L.; Wang, D. Identification of pro-fibrotic cellular subpopulations in fascia of gluteal muscle contracture using single-cell RNA sequencing. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Krause, C.; Kloen, P.; Ten Dijke, P. Elevated transforming growth factor β and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediate fibrotic traits of Dupuytren’s disease fibroblasts. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2011, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Oezel, L.; Wohltmann, M.; Gondorf, N.; Wille, J.; Güven, I.; Windolf, J.; Thelen, S.; Jaekel, C.; Grotheer, V. Dupuytren’s Disease Is Mediated by Insufficient TGF-β1 Release and Degradation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shih, B.; Bayat, A. Scientific understanding and clinical management of Dupuytren disease. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2010, 6, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Border, W.A.; Noble, N.A. Transforming growth factor beta in tissue fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 331, 1286–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallas, S.L.; Sivakumar, P.; Jones, C.J.; Chen, Q.; Peters, D.M.; Mosher, D.F.; Humphries, M.J.; Kielty, C.M. Fibronectin regulates latent transforming growth factor-beta (TGF beta) by controlling matrix assembly of latent TGF beta-binding protein-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 18871–18880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasek, J.; Rayan, G.M. Correlation of alpha-smooth muscle actin expression and contraction in Dupuytren’s disease fibroblasts. J. Hand Surg. Am. 1995, 20, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karkampouna, S.; Kreulen, M.; Obdeijn, M.C.; Kloen, P.; Dorjée, A.L.; Rivellese, F.; Chojnowski, A.; Clark, I.; Kruithof-de Julio, M. Connective Tissue Degeneration: Mechanisms of Palmar Fascia Degeneration (Dupuytren’s Disease). Curr. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2016, 2, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rehman, S.; Xu, Y.; Dunn, W.B.; Day, P.J.; Westerhoff, H.V.; Goodacre, R.; Bayat, A. Dupuytren’s disease metabolite analyses reveals alterations following initial short-term fibroblast culturing. Mol. Biosyst. 2012, 8, 2274–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosakhani, N.; Guled, M.; Lahti, L.; Borze, I.; Forsman, M.; Pääkkönen, V.; Ryhänen, J.; Knuutila, S. Unique microRNA profile in Dupuytren’s contracture supports deregulation of β-catenin pathway. Mod. Pathol. 2010, 23, 1544–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riester, S.M.; Arsoy, D.; Camilleri, E.T.; Dudakovic, A.; Paradise, C.R.; Evans, J.M.; Torres-Mora, J.; Rizzo, M.; Kloen, P.; Julio, M.K.; et al. RNA sequencing reveals a depletion of collagen targeting microRNAs in Dupuytren’s disease. BMC Med. Genom. 2015, 8, 59, Erratum in BMC Med. Genom. 2016, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Koźma, E.M.; Wisowski, G.; Olczyk, K. Platelet derived growth factor BB is a ligand for dermatan sulfate chain(s) of small matrix proteoglycans from normal and fibrosis affected fascia. Biochimie 2009, 91, 1394–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloen, P. New insights in the development of Dupuytren’s contracture: A review. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1999, 52, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verjee, L.S.; Verhoekx, J.S.; Chan, J.K.; Krausgruber, T.; Nicolaidou, V.; Izadi, D.; Davidson, D.; Feldmann, M.; Midwood, K.S.; Nanchahal, J. Unraveling the signaling pathways promoting fibrosis in Dupuytren’s disease reveals TNF as a therapeutic target. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E928–E937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Berndt, A.; Kosmehl, H.; Mandel, U.; Gabler, U.; Luo, X.; Celeda, D.; Zardi, L.; Katenkamp, D. TGF beta and bFGF synthesis and localization in Dupuytren’s disease (nodular palmar fibromatosis) relative to cellular activity, myofibroblast phenotype and oncofetal variants of fibronectin. Histochem. J. 1995, 27, 1014–1020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Zeldin, Y.; Baratz, M.E.; Kathju, S.; Satish, L. Investigating the effects of Pirfenidone on TGF-β1 stimulated non-SMAD signaling pathways in Dupuytren’s disease -derived fibroblasts. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Seyhan, H.; Stromps, J.P.; Demir, E.; Fuchs, P.C.; Kopp, J. Vitamin D deficiency may stimulate fibroblasts in Dupuytren’s disease via mitochondrial increased reactive oxygen species through upregulating transforming growth factor-β1. Med. Hypotheses 2018, 116, 40–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccio, M.; Marchesini, A.; Riccio, V.; Orlando, F.; Warwick, D.; Costa, A.L.; Zavan, B.; De Francesco, F. A novel collagenase from Vibrio Alginolyticus: Experimental study for Dupuytren’s disease. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meek, R.M.; McLellan, S.; Crossan, J.F. Dupuytren’s disease. A model for the mechanism of fibrosis and its modulation by steroids. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1999, 81, 732–738, Erratum in J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1999, 81, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satish, L.; LaFramboise, W.A.; Johnson, S.; Vi, L.; Njarlangattil, A.; Raykha, C.; Krill-Burger, J.M.; Gallo, P.H.; O’Gorman, D.B.; Gan, B.S.; et al. Fibroblasts from phenotypically normal palmar fascia exhibit molecular profiles highly similar to fibroblasts from active disease in Dupuytren’s Contracture. BMC Med. Genom. 2012, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Satish, L.; O’Gorman, D.B.; Johnson, S.; Raykha, C.; Gan, B.S.; Wang, J.H.; Kathju, S. Increased CCT-eta expression is a marker of latent and active disease and a modulator of fibroblast contractility in Dupuytren’s contracture. Cell Stress. Chaperones 2013, 18, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Berndt, A.; Borsi, L.; Luo, X.; Zardi, L.; Katenkamp, D.; Kosmehl, H. Evidence of ED-B+ fibronectin synthesis in human tissues by non-radioactive RNA in situ hybridization. Investigations on carcinoma (oral squamous cell and breast carcinoma), chronic inflammation (rheumatoid synovitis) and fibromatosis (Morbus Dupuytren). Histochem. Cell Biol. 1998, 109, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layton, T.; Nanchahal, J. Recent advances in the understanding of Dupuytren’s disease. F1000Research 2019, 8, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Category | Main Findings/Alterations | References | Key Message/Implications for DD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical cytogenetics (early studies) | Trisomy 8 detected in >50% of DD fibroblast cultures; also observed in some carpal tunnel syndrome controls | [14] | Provided the first evidence that genomic instability may predispose to fibroproliferative activity in the palmar fascia |

| Subsequent cytogenetic studies | Trisomy 7; deletions of chromosomes 6 and 11; structural rearrangements in nodule-derived fibroblasts | [8,15,16,17] | Although not entirely consistent across studies, these abnormalities support clonal expansion of genetically altered fibroblasts |

| Heritability/familial clustering | Familial aggregation of DD cases, particularly in Northern European populations | [18] | Supports a strong heritable component in DD susceptibility |

| Linkage analyses | Implicated regions on chromosomes 16q and 6p, but no single causative gene identified | [19] | Indicates germline susceptibility loci without a clearly defined causal gene |

| Early GWAS findings | Susceptibility loci identified in Wnt signaling and extracellular matrix (ECM)-related genes | [20] | Demonstrates convergence between genetic risk and profibrotic molecular pathways |

| Recent GWAS studies | >26 susceptibility loci identified; variants near WNT4, SFRP4 and RSPO2 strongly associated with DD | [8,9,21] | Strengthens the link between inherited predisposition and canonical fibrogenic (Wnt/ECM) signaling pathways |

| Integrated interpretation | Somatic chromosomal instability combined with inherited genetic predisposition | [8,9,14,15,18,19,20,21] | Chromosomal instability may drive fibroblast proliferation and ECM deposition, while germline predisposition defines at-risk individuals |

| Shared features with other fibroproliferative disorders | Overlap of chromosomal abnormalities with keloids and Peyronie’s disease | [15] | Suggests a shared pathogenic architecture across fibroproliferative conditions |

| Mechanism/Category | Molecular Players/Markers | Functional Consequence | Pathogenic Relevance in DD | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| microRNA dysregulation | ↓ miR-29 family | Loss of repression of collagen genes (COL1A1, COL3A1) | ↑ Collagen I/III synthesis and ECM accumulation | [40] |

| ↓ miR-200 family | Deregulated epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and fibroblast persistence | Sustained myofibroblast phenotype | [41] | |

| Histone modification/chromatin remodeling | ↑ HDAC expression (HDAC1/2/4) | Hypoacetylation of profibrotic gene promoters | Chromatin “locking” of α-SMA and ECM genes → persistent fibrotic state | [24] |

| Redox imbalance and oxidative stress | ↑ Reactive oxygen species (ROS) | ROS activation of MAPK and TGF-β/Smad signaling | Reinforcement of fibroblast activation and collagen deposition | [10,11,42] |

| ↑ Antioxidant enzymes (SOD2, catalase) | ||||

| Mitochondrial dysfunction | Impaired oxidative phosphorylation, ΔΨm loss | Energy stress and ROS production | Promotes profibrotic signaling and metabolic reprogramming | [10,11] |

| Stromal heterogeneity (single-cell studies) | PDPN+, FAP+, TNFRSF12A+ mesenchymal subsets | Distinct fibrogenic fibroblast populations | Defines cell-specific drivers of fibrosis, absent in normal fascia | [12] |

| Proteostasis dysregulation | ↑ CCT-η (chaperonin-containing TCP-1 complex subunit) | Stabilization of α-SMA filaments and actin cytoskeleton | Maintains contractile phenotype and mechanical “memory” | [29] |

| Mechanistic Axis | Unresolved Questions/Knowledge Gaps | Recommended Future Research Directions |

|---|---|---|

| TGF-β signaling |

|

|

| Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway |

|

|

| ECM Feedback and Mechanotransduction |

|

|

| Immune and Inflammatory Circuits |

|

|

| Cytoskeletal Stabilization and Contractility |

|

|

| Epigenetic and Redox Regulation |

|

|

| Translational and Preclinical Models |

|

|

| Clinical Stratification and Therapy Design |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pirri, C. Palmar Fascia Fibrosis in Dupuytren’s Disease: A Narrative Review of Pathogenic Mechanisms and Molecular Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010382

Pirri C. Palmar Fascia Fibrosis in Dupuytren’s Disease: A Narrative Review of Pathogenic Mechanisms and Molecular Insights. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):382. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010382

Chicago/Turabian StylePirri, Carmelo. 2026. "Palmar Fascia Fibrosis in Dupuytren’s Disease: A Narrative Review of Pathogenic Mechanisms and Molecular Insights" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010382

APA StylePirri, C. (2026). Palmar Fascia Fibrosis in Dupuytren’s Disease: A Narrative Review of Pathogenic Mechanisms and Molecular Insights. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010382