Circulating Tumor Cells for the Monitoring of Lung Cancer Therapies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Circulating Tumor Cells

2.1. CTCs Biology

2.2. CTCs Interactions in the Bloodstream

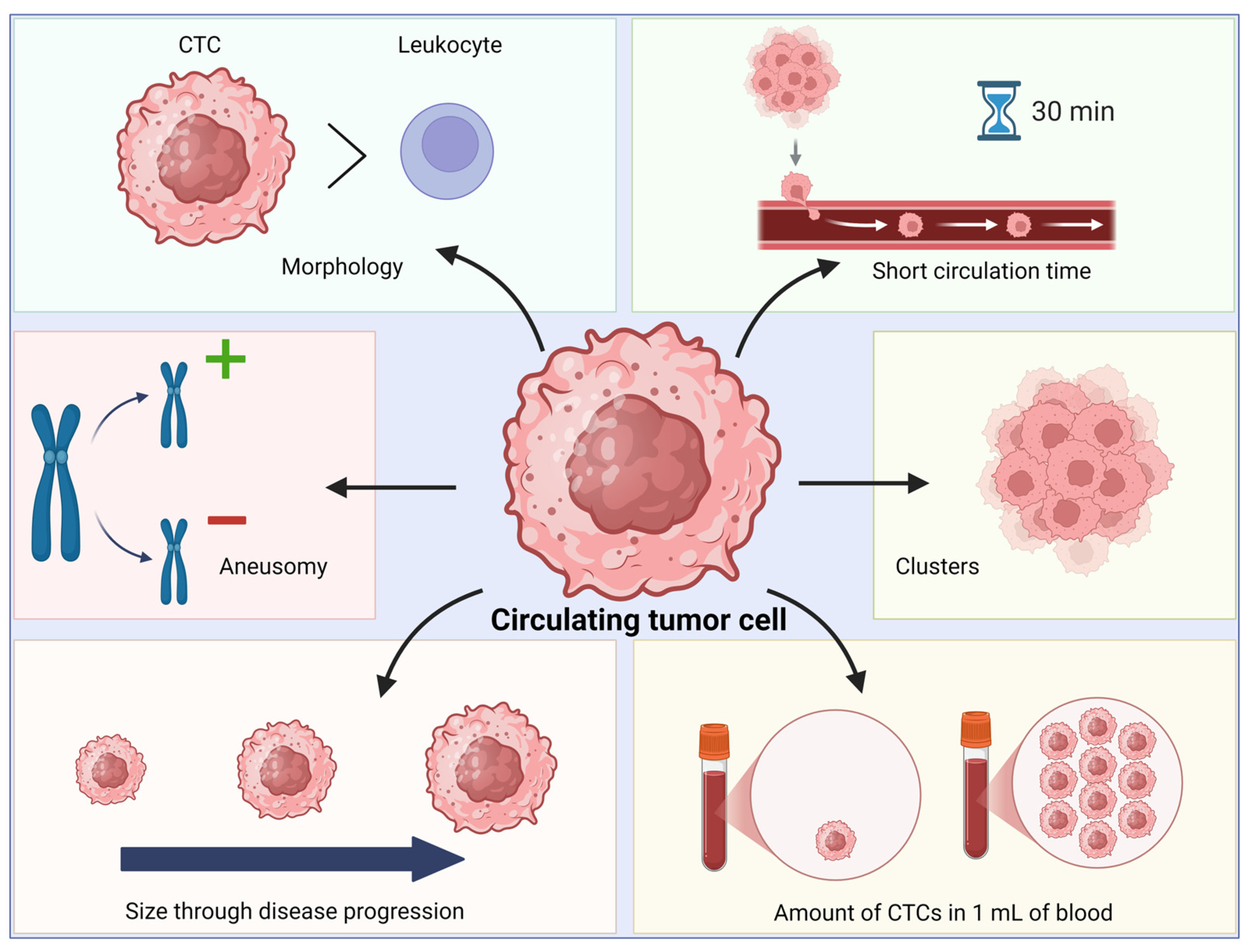

2.3. Biological, Biochemical and Biophysical Characteristics of CTCs

3. CTC Enrichment and Analysis Methods

3.1. Immunoaffinity Strategy

3.2. Strategy Utilizing Cell Surface Charge

3.3. Strategy Based on Dielectric Properties

3.4. Strategies Based on Cell Size and Compression

3.5. Nanoscale Imaging Tools Combined with Microfluidic Platforms

3.6. Combining CTC Enumeration Methods with Other Approaches

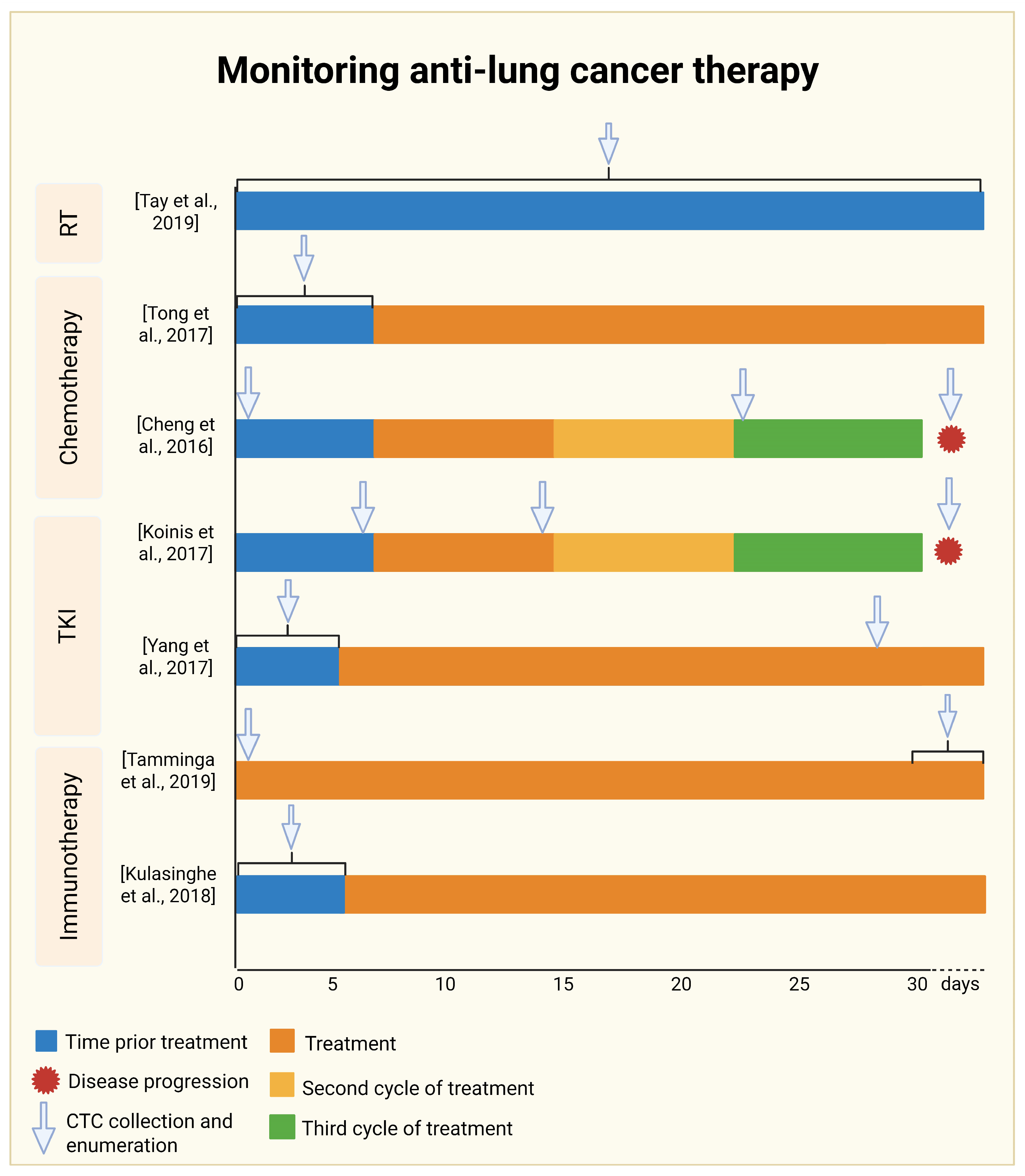

4. Monitoring Anti-Lung Cancer Therapy

4.1. Monitoring Radiotherapy

4.2. Monitoring Chemotherapy

4.3. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Therapy Monitoring

4.4. Monitoring Immunotherapy

4.5. Meta-Analysis

5. Limitations of Technologies for CTC Enumeration

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFM | Atomic force microscopy |

| AFM-FS | AFM-force spectroscopy |

| AFM-IR | Infrared nanospectroscopy |

| ALK | Anaplastic lymphoma kinase |

| CAFs | Cancer-associated fibroblasts |

| CAR | Chimeric Antigen Receptor |

| cfDNA | Cell-free DNA |

| CFRT | Conventional Fraction Radiotherapy |

| CK18 | Caspase-cleaved cytokeratin 18 |

| c-Kit | Proto-Oncogene C-KIT |

| CTCs | Circulating tumor cells |

| ctDNA | Circulating tumor DNA |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 |

| CXCL12 | C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 12 |

| DALYs | Disability-Adjusted Life Years |

| DEP | Dielectrophoresis |

| DLD | Deterministic lateral displacement |

| EGF | Epidermal growth factor |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| E/M | Epithelial and mesenchymal states |

| EMT | Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| EpCAM | Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule |

| ES-SCLC | Extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FISH | Fluorescence in situ hybridization |

| GBD | Global Burden of Disease |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| HS-AFM | High-Speed AFM |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 |

| ICIs | Immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| IF1 | Inertial focusing stage 1 |

| IF2 | Inertial focusing stage 2 |

| iFISH | Immunostaining fluorescence in situ hybridization |

| LS-SCLC | Limited-stage SCLC |

| MACS1 | Magnetically activated cell sorting stage 1 |

| MACS2 | Magnetically activated cell sorting stage 2 |

| M-CSF | Macrophage-Colony Stimulating Factor |

| MDSCs | Myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| MET | Mesenchymal–epithelial transition |

| n.a. | Not applicable |

| nDEP | Negative dielectrophoresis |

| NETs | Neutrophil extracellular traps |

| NFκB | Nuclear Factor Kappa B |

| NGS | Next-Generation Sequencing |

| NK | Natural Killer |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| OS | Overall survival |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative phosphorylation |

| qPCR | Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PARP | Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PD-1 | Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 |

| pDEP | Positive dielectrophoresis |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Cell Death-Ligand 1 |

| PDGFRs α/ß | Platelet-derived Growth Factor Receptors α/ß |

| PDMS | Poludimethylsiloxane |

| PEI | Poly(ethyleneimine) |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| PI | Poly(ethyleneimine) |

| PMN-MDSCs | Polymorphonuclear-myeloid derived suppressor cells |

| PSA | Prostate-Specific Antigen |

| PSMA | Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| ROSE | Rapid onsite evaluation |

| RT | Radiotherapy |

| SCLC | Small cell lung cancer |

| SCS | Single Cell Sequencing |

| Snail1/2 | Snail Family Transcriptional Repressors 1/2 |

| SPPCNs | Superparamagnetic positively charged nanoparticles |

| TBL | Trachea, bronchus, and lung |

| TDLNs | Tumor-Draining lymph nodes |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-β |

| TKIs | Tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TWIST | TWIST family of basic helix–loop–helix factors |

| VEGFR 1–3 | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 1–3 |

| YLDs | Years Lived with Disability |

| YLLs | Years of Life Lost |

| ZEB1/2 | Zinc-finger E-box-binding homeobox factors 1/2 |

References

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Laversanne, M.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2024; Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/today (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Kocarnik, J.M.; Compton, K.; Dean, F.E.; Fu, W.; Gaw, B.L.; Harvey, J.D.; Henrikson, H.J.; Lu, D.; Pennini, A.; Xu, R.; et al. Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years for 29 Cancer Groups From 2010 to 2019. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 420–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahiri, A.; Maji, A.; Potdar, P.D.; Singh, N.; Parikh, P.; Bisht, B.; Mukherjee, A.; Paul, M.K. Lung Cancer Immunotherapy: Progress, Pitfalls, and Promises. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Xia, F.; Lin, R. Global Burden of Cancer and Associated Risk Factors in 204 Countries and Territories, 1980–2021: A Systematic Analysis for the GBD 2021. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, W.; Tian, L.; Xu, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, T. Multimodal Framework in Lung Cancer Management: Integrating Liquid Biopsy with Traditional Diagnostic Techniques. CMAR 2025, 17, 461–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagrande, G.M.S.; Silva, M.d.O.; Reis, R.M.; Leal, L.F. Liquid Biopsy for Lung Cancer: Up-to-Date and Perspectives for Screening Programs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.-S.; Deng, B.; Feng, Y.-G.; Qian, K.; Tan, Q.-Y.; Wang, R.-W. Circulating Tumor Cells Prior to Initial Treatment Is an Important Prognostic Factor of Survival in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-Analysis and System Review. BMC Pulm. Med. 2019, 19, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, K.; Xu, J.; Huang, J.; Zhang, T. Prognostic Significance of Circulating Tumor Cells in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78070, Correction in PLoS ONE 2014, 9. https://doi.org/10.1371/annotation/6633ed7f-a10c-4f6d-9d1d-9c1245822eb7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, H.-T.; Li, B.-G. Prognostic Significance of Circulating Tumor Cells in Small--Cell Lung Cancer Patients: A Meta-Analysis. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 8429–8433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Lv, H.; Yu, J.; Li, H. The Detection of Circulating Tumor Cells Indicates Poor Therapeutic Efficacy and Prognosis in Patients with Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Evid. Based Med. 2024, 17, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.; Zhu, L.; Shao, J.; Yakoub, M.; Schmitt, L.; Reißfelder, C.; Loges, S.; Benner, A.; Schölch, S. Circulating Tumour Cells in Patients with Lung Cancer Universally Indicate Poor Prognosis. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2022, 31, 220151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, T.R. A Case of Cancer in Which Cells Similar to Those in the Tumors Were Seen in the Blood after Death. Austral. Med. J. 1896, 14, 146–149. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, D.; Shen, L.; Luo, M.; Zhang, K.; Li, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhu, F.; Zhou, D.; Zheng, S.; Chen, Y.; et al. Circulating Tumor Cells: Biology and Clinical Significance. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stott, S.L.; Richard, L.; Nagrath, S.; Min, Y.; Miyamoto, D.T.; Ulkus, L.; Inserra, E.J.; Ulman, M.; Springer, S.; Nakamura, Z.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of Circulating Tumor Cells from Patients with Localized and Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010, 2, 25ra23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oleksiewicz, U.; Machnik, M. Causes, Effects, and Clinical Implications of Perturbed Patterns within the Cancer Epigenome. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 83, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, G.; Rath, B. Mesenchymal-Epithelial Transition and Circulating Tumor Cells in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 994, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.R.; Perez, M.J.; Munson, J.M. Docetaxel Facilitates Lymphatic-Tumor Crosstalk to Promote Lymphangiogenesis and Cancer Progression. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Watts, J.A.; Jamshidi-Parsian, A.; Nadeem, U.; Sarimollaoglu, M.; Siegel, E.R.; Zharov, V.P.; Galanzha, E.I. In Vivo Lymphatic Circulating Tumor Cells and Progression of Metastatic Disease. Cancers 2020, 12, 2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, E.; Cao, T.; Nagrath, S.; King, M.R. Circulating Tumor Cells: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 20, 329–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Fei, Q.; Qiu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Sun, L. Liquid Biopsy Techniques and Lung Cancer: Diagnosis, Monitoring and Evaluation. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; He, J.; Zhang, B.; Wang, L.; Long, C.; Zhao, B.; Yang, Y.; Du, L.; Luo, W.; Hu, J.; et al. A Potential “Anti-Warburg Effect” in Circulating Tumor Cell-Mediated Metastatic Progression? Aging Dis. 2023, 16, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, M.; Lam, J.N.; Walser, T.; Dubinett, S.M.; Rettig, M.B.; Carlo, D.D. Functional Profiling of Circulating Tumor Cells with an Integrated Vortex Capture and Single-Cell Protease Activity Assay. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 9986–9991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canciello, A.; Cerveró-Varona, A.; Peserico, A.; Mauro, A.; Russo, V.; Morrione, A.; Giordano, A.; Barboni, B. “In Medio Stat Virtus”: Insights into Hybrid E/M Phenotype Attitudes. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 1038841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasani, S.; Sahoo, S.; Jolly, M.K. Hybrid E/M Phenotype(s) and Stemness: A Mechanistic Connection Embedded in Network Topology. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastushenko, I.; Mauri, F.; Song, Y.; Cock, F.D.; Meeusen, B.; Swedlund, B.; Impens, F.; Haver, D.V.; Opitz, M.; Thery, M.; et al. Fat1 Deletion Promotes Hybrid EMT State, Tumour Stemness and Metastasis. Nature 2021, 589, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, B.; Tewes, M.; Fehm, T.; Hauch, S.; Kimmig, R.; Kasimir-Bauer, S. Stem Cell and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Markers Are Frequently Overexpressed in Circulating Tumor Cells of Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2009, 11, R46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadaki, M.A.; Stoupis, G.; Theodoropoulos, P.A.; Mavroudis, D.; Georgoulias, V.; Agelaki, S. Circulating Tumor Cells with Stemness and Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Features Are Chemoresistant and Predictive of Poor Outcome in Metastatic Breast Cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2019, 18, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y.; Shi, D. Circulating Tumor Cell Isolation for Cancer Diagnosis and Prognosis. eBioMedicine 2022, 83, 104237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiri, S.; Ryba, T. Cancer, Metastasis, and the Epigenome. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Wei, S.; Lv, X. Circulating Tumor Cells: From New Biological Insights to Clinical Practice. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Li, S.; Hu, X.; Sun, M.; Wu, Q.; Dai, H.; Tan, Y.; Sun, F.; Wang, C.; Rong, X.; et al. Shear Stress Activates ATOH8 via Autocrine VEGF Promoting Glycolysis Dependent-Survival of Colorectal Cancer Cells in the Circulation. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. CR 2020, 39, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Li, K.; Xin, Y.; Tan, K.; Yang, M.; Wang, G.; Tan, Y. Fluid Shear Stress Regulates the Survival of Circulating Tumor Cells via Nuclear Expansion. J. Cell Sci. 2022, 135, jcs259586, Correction in J. Cell Sci. 2023, 136, jcs261030. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.261030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.Y.; Yang, G.-M.; Dayem, A.A.; Saha, S.K.; Kim, K.; Yoo, Y.; Hong, K.; Kim, J.-H.; Yee, C.; Lee, K.-M.; et al. Hydrodynamic Shear Stress Promotes Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition by Downregulating ERK and GSK3β Activities. Breast Cancer Res. 2019, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, Y.; Li, K.; Yang, M.; Tan, Y. Fluid Shear Stress Induces Emt of Circulating Tumor Cells via Jnk Signaling in Favor of Their Survival during Hematogenous Dissemination. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, Y.; Hu, B.; Li, K.; Hu, G.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Tang, K.; Du, P.; Tan, Y. Circulating Tumor Cells with Metastasis-Initiating Competence Survive Fluid Shear Stress during Hematogenous Dissemination through CXCR4-PI3K/AKT Signaling. Cancer Lett. 2024, 590, 216870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceto, N.; Bardia, A.; Miyamoto, D.T.; Donaldson, M.C.; Wittner, B.S.; Spencer, J.A.; Yu, M.; Pely, A.; Engstrom, A.; Zhu, H.; et al. Circulating Tumor Cell Clusters Are Oligoclonal Precursors of Breast Cancer Metastasis. Cell 2014, 158, 1110–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczerba, B.M.; Castro-Giner, F.; Vetter, M.; Krol, I.; Gkountela, S.; Landin, J.; Scheidmann, M.C.; Donato, C.; Scherrer, R.; Singer, J.; et al. Neutrophils Escort Circulating Tumour Cells to Enable Cell Cycle Progression. Nature 2019, 566, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanikarla-Marie, P.; Lam, M.; Menter, D.G.; Kopetz, S. Platelets, Circulating Tumor Cells, and the Circulome. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2017, 36, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedl, P.; Locker, J.; Sahai, E.; Segall, J.E. Classifying Collective Cancer Cell Invasion. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labelle, M.; Begum, S.; Hynes, R.O. Direct Signaling Between Platelets and Cancer Cells Induces an Epithelial-Mesenchymal-Like Transition and Promotes Metastasis. Cancer Cell 2011, 20, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Navas, C.; Miguel-Pérez, D.d.; Exposito-Hernandez, J.; Bayarri, C.; Amezcua, V.; Ortigosa, A.; Valdivia, J.; Guerrero, R.; Puche, J.L.G.; Lorente, J.A.; et al. Cooperative and Escaping Mechanisms between Circulating Tumor Cells and Blood Constituents. Cells 2019, 8, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Fu, C.; Wagner, D.; Guo, H.; Zhan, D.; Dong, C.; Long, M. Two-Dimensional Kinetics of Beta 2-Integrin and ICAM-1 Bindings between Neutrophils and Melanoma Cells in a Shear Flow. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2008, 294, C743–C753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiegel, A.; Brooks, M.W.; Houshyar, S.; Reinhardt, F.; Ardolino, M.; Fessler, E.; Chen, M.B.; Krall, J.A.; Decock, J.; Zervantonakis, I.K.; et al. Neutrophils Suppress Intraluminal NK Cell-Mediated Tumor Cell Clearance and Enhance Extravasation of Disseminated Carcinoma Cells. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 630–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cools-Lartigue, J.; Spicer, J.; McDonald, B.; Gowing, S.; Chow, S.; Giannias, B.; Bourdeau, F.; Kubes, P.; Ferri, L. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Sequester Circulating Tumor Cells and Promote Metastasis. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 3446–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Qiao, X.; Shi, H.; Han, X.; Liu, W.; Tian, X.; Zeng, X. Circulating Tumor-Associated Neutrophils (cTAN) Contribute to Circulating Tumor Cell Survival by Suppressing Peripheral Leukocyte Activation. Tumour Biol. J. Int. Soc. Oncodevelopm. Biol. Med. 2016, 37, 5397–5404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffelt, S.B.; Kersten, K.; Doornebal, C.W.; Weiden, J.; Vrijland, K.; Hau, C.-S.; Verstegen, N.J.M.; Ciampricotti, M.; Hawinkels, L.J.A.C.; Jonkers, J.; et al. IL17-Producing Γδ T Cells and Neutrophils Conspire to Promote Breast Cancer Metastasis. Nature 2015, 522, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprouse, M.L.; Welte, T.; Boral, D.; Liu, H.N.; Yin, W.; Vishnoi, M.; Goswami-Sewell, D.; Li, L.; Pei, G.; Jia, P.; et al. PMN-MDSCs Enhance CTC Metastatic Properties through Reciprocal Interactions via ROS/Notch/Nodal Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, Y.; Safi, S.; Blattner, C.; Rathinasamy, A.; Umansky, L.; Juenger, S.; Warth, A.; Eichhorn, M.; Muley, T.; Herth, F.J.F.; et al. Circulating and Tumor Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Resectable Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, P.; Martínez-Pena, I.; Piñeiro, R. Dangerous Liaisons: Circulating Tumor Cells (Ctcs) and Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (Cafs). Cancers 2020, 12, 2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cords, L.; Tietscher, S.; Anzeneder, T.; Langwieder, C.; Rees, M.; de Souza, N.; Bodenmiller, B. Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Classification in Single-Cell and Spatial Proteomics Data. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaggioli, C.; Hooper, S.; Hidalgo-Carcedo, C.; Grosse, R.; Marshall, J.F.; Harrington, K.; Sahai, E. Fibroblast-Led Collective Invasion of Carcinoma Cells with Differing Roles for RhoGTPases in Leading and Following Cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 1392–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vona, G.; Sabile, A.; Louha, M.; Sitruk, V.; Romana, S.; Schutze, K.; Capron, F.; Franco, D.; Pazzagli, M.; Vekemans, M.; et al. Isolation by Size of Epithelial Tumor Cells: A New Method for the Immunomorphological and Molecular Characterization of Circulating Tumor Cells. Am. J. Pathol. 2000, 156, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankó, P.; Lee, S.Y.; Nagygyörgy, V.; Zrínyi, M.; Chae, C.H.; Cho, D.H.; Telekes, A. Technologies for Circulating Tumor Cell Separation from Whole Blood. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid-Schonbein, G.W.; Shih, Y.Y.; Chien, S. Morphometry of Human Leukocytes. Blood 1980, 56, 866–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendelaar, P.A.J.; Kraan, J.; Van, M.; Zeune, L.L.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M.; Hoop, E.O.; Martens, J.W.M.; Sleijfer, S. Defining the Dimensions of Circulating Tumor Cells in a Large Series of Breast, Prostate, Colon, and Bladder Cancer Patients. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 15, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Tong, L.; Gao, Y.; Hu, F.; Lin, P.P.; Li, B.; Zhang, T. Vimentin Expression in Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) Associated with Liver Metastases Predicts Poor Progression-Free Survival in Patients with Advanced Lung Cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 145, 2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Tripathy, D.; Frenkel, E.P.; Shete, S.; Naftalis, E.Z.; Huth, J.F.; Beitsch, P.D.; Leitch, M.; Hoover, S.; Euhus, D.; et al. Circulating Tumor Cells in Patients with Breast Cancer Dormancy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 8152–8162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, E.; Basso, U.; Celadin, R.; Zilio, F.; Pucciarelli, S.; Aieta, M.; Barile, C.; Sava, T.; Bonciarelli, G.; Tumolo, S.; et al. M30 Neoepitope Expression in Epithelial Cancer: Quantification of Apoptosis in Circulating Tumor Cells by CellSearch Analysis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 5233–5243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabisiewicz, A.; Grzybowska, E. CTC Clusters in Cancer Progression and Metastasis. Med. Oncol. 2017, 34, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmiero, M.; Cantarosso, I.; di Blasio, L.; Monica, V.; Peracino, B.; Primo, L.; Puliafito, A. Collective Directional Migration Drives the Formation of Heteroclonal Cancer Cell Clusters. Mol. Oncol. 2023, 17, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, M.M.; Lynch, C.C. How Circulating Tumor Cluster Biology Contributes to the Metastatic Cascade: From Invasion to Dissemination and Dormancy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2023, 42, 1133–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taftaf, R.; Liu, X.; Singh, S.; Jia, Y.; Dashzeveg, N.K.; Hoffmann, A.D.; El-Shennawy, L.; Ramos, E.K.; Adorno-Cruz, V.; Schuster, E.J.; et al. ICAM1 Initiates CTC Cluster Formation and Trans-Endothelial Migration in Lung Metastasis of Breast Cancer. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aceto, N. Bring along Your Friends: Homotypic and Heterotypic Circulating Tumor Cell Clustering to Accelerate Metastasis. Biomed. J. 2020, 43, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cubero, M.J.A.; Lorente, J.A.; Robles-Fernandez, I.; Rodriguez-Martinez, A.; Puche, J.L.; Serrano, M.J. Circulating Tumor Cells: Markers and Methodologies for Enrichment and Detection. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1634, 283–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, J.B.; Hou, L.K.; Yu, F.; Zhang, J.; Wu, W.; Tang, X.M.; Sun, F.; Lu, H.M.; Deng, J.; et al. Liquid Biopsy in Lung Cancer: Significance in Diagnostics, Prediction, and Treatment Monitoring. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikanjam, M.; Kato, S.; Kurzrock, R. Liquid Biopsy: Current Technology and Clinical Applications. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasik, B.; Skrzypski, M.; Bieńkowski, M.; Dziadziuszko, R.; Jassem, J. Current and Future Applications of Liquid Biopsy in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer—A Narrative Review. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2023, 12, 594–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, W.J.; Matera, J.; Miller, M.C.; Repollet, M.; Connelly, M.C.; Rao, C.; Tibbe, A.G.J.; Uhr, J.W.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M. Tumor Cells Circulate in the Peripheral Blood of All Major Carcinomas but Not in Healthy Subjects or Patients with Nonmalignant Diseases. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 6897–6904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolovic, D.; Galindo, L.; Carstens, A.; Rahbari, N.; Büchler, M.W.; Weitz, J.; Koch, M. Heterogeneous Detection of Circulating Tumor Cells in Patients with Colorectal Cancer by Immunomagnetic Enrichment Using Different EpCAM-Specific Antibodies. BMC Biotechnol. 2010, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Gu, L.; Qin, J.; Zhang, L.; Sun, F.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Shi, D. Rapid Label-Free Isolation of Circulating Tumor Cells from Patients’ Peripheral Blood Using Electrically Charged Fe3O4 Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 4193–4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.-K.; Chou, W.-P.; Huang, S.-B.; Wang, H.-M.; Lin, Y.-C.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Wu, M.-H. Application of Optically-Induced-Dielectrophoresis in Microfluidic System for Purification of Circulating Tumour Cells for Gene Expression Analysis- Cancer Cell Line Model. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccioli, M.; Kim, K.; Khazan, N.; Khoury, J.D.; Cooke, M.J.; Miller, M.C.; O’Shannessy, D.J.; Pailhes-Jimenez, A.-S.; Moore, R.G. Identification of Circulating Tumor Cells Captured by the FDA-Cleared Parsortix® PC1 System from the Peripheral Blood of Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients Using Immunofluorescence and Cytopathological Evaluations. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deliorman, M.; Janahi, F.K.; Sukumar, P.; Glia, A.; Alnemari, R.; Fadl, S.; Chen, W.; Qasaimeh, M.A. AFM-Compatible Microfluidic Platform for Affinity-Based Capture and Nanomechanical Characterization of Circulating Tumor Cells. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2020, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szerenyi, D.; Jarvas, G.; Guttman, A. Multifaceted Approaches in Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule-Mediated Circulating Tumor Cell Isolation. Molecules 2025, 30, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoecklein, N.H.; Fischer, J.C.; Niederacher, D.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M. Challenges for CTC-Based Liquid Biopsies: Low CTC Frequency and Diagnostic Leukapheresis as a Potential Solution. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn 2016, 16, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzpis, M.; McLaughlin, P.M.J.; Leij, L.M.F.H.D.; Harmsen, M.C. Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule: More than a Carcinoma Marker and Adhesion Molecule. Am. J. Pathol. 2007, 171, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondi, C.; Nicolazzo, C.; Gradilone, A. Circulating Tumor Cells Isolation: “The Post-EpCAM Era”. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 2015, 27, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardingham, J.E.; Kotasek, D.; Farmer, B.; Butler, R.N.; Mi, J.-X.; Sage, R.E.; Dobrovic, A. Immunobead-PCR: A Technique for the Detection of Circulating Tumor Cells Using Immunomagnetic Beads and the Polymerase Chain Reaction. Cancer Res. 1993, 53, 3455–3458. [Google Scholar]

- Andree, K.C.; van Dalum, G.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M. Challenges in Circulating Tumor Cell Detection by the CellSearch System. Mol. Oncology 2016, 10, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorges, T.M.; Tinhofer, I.; Drosch, M.; Röse, L.; Zollner, T.M.; Krahn, T.; Ahsen, O. von Circulating Tumour Cells Escape from EpCAM-Based Detection Due to Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Po, J.W.; Roohullah, A.; Lynch, D.; DeFazio, A.; Harrison, M.; Harnett, P.R.; Kennedy, C.; de Souza, P.; Becker, T.M. Improved Ovarian Cancer EMT-CTC Isolation by Immunomagnetic Targeting of Epithelial EpCAM and Mesenchymal N-Cadherin. J. Circ. Biomark. 2018, 7, 1849454418782617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Le, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, D.; Ren, L.; Lin, L.; Cui, S.; Hu, J.J.; Hu, Y.; et al. Targeting Negative Surface Charges of Cancer Cells by Multifunctional Nanoprobes. Theranostics 2016, 6, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; McFaul, S.M.; Duffy, S.P.; Deng, X.; Tavassoli, P.; Black, P.C.; Ma, H. Technologies for Label-Free Separation of Circulating Tumor Cells: From Historical Foundations to Recent Developments. Lab Chip 2014, 14, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, F.F.; Wang, X.B.; Huang, Y.; Pethig, R.; Vykoukal, J.; Gascoyne, P.R.C. Separation of Human Breast Cancer Cells from Blood by Differential Dielectric Affinity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 860–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, K.; Zhu, H.; Ma, X. Liquid Biopsy of Circulating Tumor Cells: From Isolation, Enrichment, and Genome Sequencing to Clinical Applications. Histol. Histopathol. 2025, 40, 1529–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabacak, N.M.; Spuhler, P.S.; Fachin, F.; Lim, E.J.; Pai, V.; Ozkumur, E.; Martel, J.M.; Kojic, N.; Smith, K.; Chen, P.; et al. Microfluidic, Marker-Free Isolation of Circulating Tumor Cells from Blood Samples. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9, 694–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fachin, F.; Spuhler, P.; Martel-Foley, J.M.; Edd, J.F.; Barber, T.A.; Walsh, J.; Karabacak, M.; Pai, V.; Yu, M.; Smith, K.; et al. Monolithic Chip for High-Throughput Blood Cell Depletion to Sort Rare Circulating Tumor Cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Mao, X.; Imrali, A.; Syed, F.; Mutsvangwa, K.; Berney, D.; Cathcart, P.; Hines, J.; Shamash, J.; Lu, Y.J. Optimization and Evaluation of a Novel Size Based Circulating Tumor Cell Isolation System. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, V.M.; Oner, E.; Ward, M.P.; Hurley, S.; Henderson, B.D.; Lewis, F.; Finn, S.P.; Fitzmaurice, G.J.; O’Leary, J.J.; O’Toole, S.; et al. A Comparative Study of Circulating Tumor Cell Isolation and Enumeration Technologies in Lung Cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2025, 19, 2014–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcuello, C.; Lim, K.; Nisini, G.; Pokrovsky, V.S.; Conde, J.; Ruggeri, F.S. Nanoscale Analysis beyond Imaging by Atomic Force Microscopy: Molecular Perspectives on Oncology and Neurodegeneration. Small Sci. 2025, 5, 2500351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugai, K.; Mori, T.; Bilal, T.; Furukawa, A.; Sekine, Y.; Kobayashi, N.; Kikuchi, S.; Goto, Y.; Ichimura, H.; Masuda, T.; et al. Detection of Circulating Tumor Cells in Patients with Lung Cancer Using a Rare Cell Sorter: A Pilot Study. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Rong, Y.; Yi, K.; Huang, L.; Chen, M.; Wang, F. Circulating Tumor Cells in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Single-Cell Based Analysis, Preclinical Models, and Clinical Applications. Theranostics 2020, 10, 12060–12071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Xu, Z.; Kong, F.; Huang, X.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, W.; Ye, S.; Ye, Q. Circulating Tumour Cell Combined with DNA Methylation for Early Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1065693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fielding, D.I.; Dalley, A.J.; Singh, M.; Nandakumar, L.; Lakis, V.; Chittoory, H.; Fairbairn, D.; Patch, A.; Kazakoff, S.H.; Ferguson, K.; et al. Evaluating Diff-Quik Cytology Smears for Large-panel Mutation Testing in Lung Cancer—Predicting DNA Content and Success with Low-malignant-cellularity Samples. Cancer Cytopathol. 2023, 131, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neville, A. Lung Cancer. BMJ Clin. Evid. 2009, 2009, 1504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hong, W.S.; Wang, S.G.; Zhang, G.Q. Lung Cancer Radiotherapy: Simulation and Analysis Based on a Multicomponent Mathematical Model. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2021, 2021, 6640051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinod, S.K.; Hau, E. Radiotherapy Treatment for Lung Cancer: Current Status and Future Directions. Respirology 2020, 25, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, R.Y.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, F.; Foy, V.; Burns, K.; Pierce, J.; Morris, K.; Priest, L.; Tugwood, J.; Ashcroft, L.; Lindsay, C.R.; et al. Prognostic Value of Circulating Tumour Cells in Limited-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Analysis of the Concurrent Once-Daily versus Twice-Daily Radiotherapy (CONVERT) Randomised Controlled Trial. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1114–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faivre-Finn, C.; Snee, M.; Ashcroft, L.; Appel, W.; Barlesi, F.; Bhatnagar, A.; Bezjak, A.; Cardenal, F.; Fournel, P.; Harden, S.; et al. Concurrent Once-Daily versus Twice-Daily Chemoradiotherapy in Patients with Limited-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer (CONVERT): An Open-Label, Phase 3, Randomised, Superiority Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1116–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, B.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Chen, M.; Xing, J.; Zhong, W.; Wang, M. Prognostic Significance of Circulating Tumor Cells in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 86615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Liu, X.Q.; Fan, Y.; Liu, Y.P.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ma, L.X.; Liu, X.H.; Li, H.; Bao, H.Z.; et al. Circulating Tumor Cell Counts/Change for Outcome Prediction in Patients with Extensive-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Future Oncol. 2016, 12, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koinis, F.; Agelaki, S.; Karavassilis, V.; Kentepozidis, N.; Samantas, E.; Peroukidis, S.; Katsaounis, P.; Hartabilas, E.; Varthalitis, I.I.; Messaritakis, I.; et al. Second-Line Pazopanib in Patients with Relapsed and Refractory Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Multicentre Phase II Study of the Hellenic Oncology Research Group. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 117, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Qin, A.; Zhang, K.; Ren, H.; Liu, S.; Liu, X.; Pan, X.; Yu, G. Circulating Tumor Cells Predict Prognosis Following Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Treatment in EGFR-Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Oncol. Res. 2017, 25, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamminga, M.; Wit, S.D.; Hiltermann, T.J.N.; Timens, W.; Schuuring, E.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M.; Groen, H.J.M. Circulating Tumor Cells in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients Are Associated with Worse Tumor Response to Checkpoint Inhibitors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulasinghe, A.; Kapeleris, J.; Kimberley, R.; Mattarollo, S.R.; Thompson, E.W.; Thiery, J.P.; Kenny, L.; O’Byrne, K.; Punyadeera, C. The Prognostic Significance of Circulating Tumor Cells in Head and Neck and Non-small-cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 5910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, L.S.; Wintrobe, M.M.; Dameshek, W.; Goodman, M.J.; Gilman, A.; Mclennan, M.T. NITROGEN MUSTARD THERAPY: Use of Methyl-Bis(Beta-Chloroethyl)Amine Hydrochloride and Tris(Beta-Chloroethyl)Amine Hydrochloride for Hodgkin’s Disease, Lymphosarcoma, Leukemia and Certain Allied and Miscellaneous Disorders. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1946, 132, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yan, B.; He, S. Advances and Challenges in the Treatment of Lung Cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 169, 115891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietanza, M.C.; Waqar, S.N.; Krug, L.M.; Dowlati, A.; Hann, C.L.; Chiappori, A.; Owonikoko, T.K.; Woo, K.M.; Cardnell, R.J.; Fujimoto, J.; et al. Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase II Study of Temozolomide in Combination With Either Veliparib or Placebo in Patients with Relapsed-Sensitive or Refractory Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2386–2394, Erratum in J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2898. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2018.18.01142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Xie, L.; Hong, J. Next-Generation EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors to Overcome C797S Mutation in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (2019–2024). RSC Med. Chem. 2024, 15, 3371–3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, S.H.; Kilvert, H.; Candlish, J.; Lee, B.; Polli, A.; Thomaidou, D.; Le, H. Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Lorlatinib with Comparison to Other Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK) Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKIs) as First-Line Treatment for ALK-Positive Advanced Non-Smallcell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). Lung Cancer 2024, 197, 107968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Jiang, S.; Shi, Y. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors for Solid Tumors in the Past 20 Years (2001–2020). J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zheng, D.; Zeng, Υ.; Qin, A.; Gao, J.; Yu, G. Circulating Tumor Cells Predict Prognosis Following Second- Line AZD 9291 Treatment in EGFR-T790M Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. J. BUON 2018, 23, 1077–1081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rui, R.; Zhou, L.; He, S. Cancer Immunotherapies: Advances and Bottlenecks. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1212476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, P.C.; Popa, X.; Martínez, O.; Mendoza, S.; Santiesteban, E.; Crespo, T.; Amador, R.M.; Fleytas, R.; Acosta, S.C.; Otero, Y.; et al. A Phase III Clinical Trial of the Epidermal Growth Factor Vaccine CIMAvax-EGF as Switch Maintenance Therapy in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 3782–3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quoix, E.; Ramlau, R.; Westeel, V.; Papai, Z.; Madroszyk, A.; Riviere, A.; Koralewski, P.; Breton, J.L.; Stoelben, E.; Braun, D.; et al. Therapeutic Vaccination with TG4010 and First-Line Chemotherapy in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Controlled Phase 2B Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 1125–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaccone, G.; Bazhenova, L.A.; Nemunaitis, J.; Tan, M.; Juhász, E.; Ramlau, R.; Heuvel, M.M.V.D.; Lal, R.; Kloecker, G.H.; Eaton, K.D.; et al. A Phase III Study of Belagenpumatucel-L, an Allogeneic Tumour Cell Vaccine, as Maintenance Therapy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2015, 51, 2321–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondelo-Macía, P.; García-González, J.; León-Mateos, L.; Anido, U.; Aguín, S.; Abdulkader, I.; Sánchez-Ares, M.; Abalo, A.; Rodríguez-Casanova, A.; Díaz-Lagares, Á.; et al. Clinical Potential of Circulating Free DNA and Circulating Tumour Cells in Patients with Metastatic Non-small-cell Lung Cancer Treated with Pembrolizumab. Mol. Oncol. 2021, 15, 2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.-X.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, H.-L.; Pan, H.-M.; Han, W.-D. Circulating Tumor Cells Predict Survival Benefit from Chemotherapy in Patients with Lung Cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 67586–67596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalik, A.; Kowalewska, M.; Góźdź, S. Current Approaches for Avoiding the Limitations of Circulating Tumor Cells Detection Methods—Implications for Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients with Solid Tumors. Transl. Res. 2017, 185, 58–84.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, N.; Yang, X.; Li, J.; Long, S. Prognostic Significance of Programmed Cell Death-Ligand 1 Expression on Circulating Tumor Cells in Various Cancers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 7021–7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilié, M.; Mazières, J.; Chamorey, E.; Heeke, S.; Benzaquen, J.; Thamphya, B.; Boutros, J.; Tiotiu, A.; Fayada, J.; Cadranel, J.; et al. Prospective Multicenter Validation of the Detection of ALK Rearrangements of Circulating Tumor Cells for Noninvasive Longitudinal Management of Patients With Advanced NSCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021, 16, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntzifa, A.; Marras, T.; Kallergi, G.; Kotsakis, A.; Georgoulias, V.; Lianidou, E. Comprehensive Liquid Biopsy Analysis for Monitoring NSCLC Patients under Second-Line Osimertinib Treatment. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1435537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Enrichment Method | Detection Marker(s)/Feature(s) | Advantages | Limitations | Specificity * | Sensitivity (% of Patients with Detected CTC/CTCs) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CellSearch | EpCAM, DAPI, CK8, CK18 and/or CK19 (+) CD45 (−) | Standardization, reproducibility, analytical performance, flexibility in preparation, wide range of clinical applications | Hard to detect CTCs in early stages of disease, unable to detect CTCs with lost EpCAM expression during EMT | 99.7% (≥2 CTCs/7.5 mL of blood sample) [68] | 20% metastatic lung cancer patients [68] |

| Dynabeads | Magnetic potential + anti-EpCAM antibody + RT-PCR assay for CK20 expression | Easy and fast isolation, high purity and efficiency, precise particle binding, easy automatization | Unable to detect CTCs with lost expression of EpCAM during EMT | 100% [69] | 103 spiked-in HT29 cells (200 cells/mL) in 5 mL; 28% colorectal cancer patients [69] |

| Superparamagnetic Positively Charged Nanoparticles (SPPCNs) | Negative surface charge of CTCs (magnetic potential) + immunofluorescence or iFISH (DAPI, EpCAM or CD45) | EpCAM-independent in the first stage | Cellular structure disturbances, need for buffer optimization | 100% [70] | 2–8 CTCs/1 mL of blood sample; 100% colorectal cancer patients [70] |

| Dielectrophoresis | Physical features: size, nuclear morphology, cell membrane morphology, dielectric properties of cells, and their membrane surface | Non-invasive, epitope independence | Requires precise control of physical conditions | not analyzed [71] | 66–84% (including epithelial-, EMT-, and CSC-CTCs) depending on the treatment status in breast cancer patients [71] |

| Parsortix | Cell size and compressibility | Low cost, simple operation, epitope independence | Similar size of CTCs and leukocytes | 93.1% [72] | 1 CTC/average 8.6 mL; 45.3% metastatic breast cancer patients [72] |

| Atomic force microscopy (AFM)-compatible microfluidic platform | EpCAM, PSA, PSMA, DAPI, CK (+) + AFM | External access to intact cells, determination of the elasticity, deformation, and cell adhesion forces | High cost, slow process, EpCAM dependent | AFM analysis of EpCAM-captured CTCs showed decreased stiffness and adhesin expression in case of metastatic prostate cancer compared to localized cancer. No specificity and sensitivity was evaluated for AFM method [73]. | |

| NCT/Reference | Disease (Stage) | Drug (Treatment) | CTC Enrichment Method | Cut-Off Threshold (CTCs/mL of Blood Sample) | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT00433563/[98] | Limited stage (LS)-SCLC | Cisplatin, Etoposide, 45 Grays in 30 fractions twice a day or 66 Grays in 33 fractions daily (Chemoradiotherapy) | CellSearch | 15 CTCs/7.5 mL blood samples | ↑ amount of CTC = ↓ time of OS and PFS |

| n.a./[100] | NSCLC (IIIB/IV) | Platinum (Chemotherapy) | Cyttel + FISH/immunofluorescence | 8 CTCs/3.2 mL blood samples | ↑ amount of CTC = ↓ time of OS and PFS |

| n.a./[101] | Extensive stage (ES)-SCLC | Etoposide-Cisplatin/Etoposide-Lobaplatin (Chemotherapy) | CellSearch | 10 CTCs/7.5 mL blood samples | ↑ amount of CTC = ↓ time of OS and PFS |

| NCT01253369/[102] | Chemotherapy-resistant SCLC | Pazopanib (Tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy) | CellSearch | 5 CTCs/7.5 mL blood samples | ↑ amount of CTC = ↓ time of OS and PFS |

| n.a./[103] | NSCLC with EGFR mutation (IIIB/IV) | Erlotinib/Gefitinib (Tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy) | CellSearch | 5 CTCs/7.5 mL blood samples | HR = 8.017 for ↓ PFS in day 28 of treatment in samples with ≥5 CTCs |

| n.a./[104] | NSCLC (IIIB/IV) | Nivolumab/Pembrolizumab/Atezolizumab/Ipilimumab and Nivolumab (Immunotherapy) | CellSearch | Detection of single CTC/7.5 mL blood samples | ↑ amount of CTCs and ↓ time of OS (HR = 2.4) ↑ amount of CTCs and ↓ time of PFS (HR = 4.46) |

| n.a./[105] | NSCLC (IV) | Nivolumab (Immunotherapy) | ClearCell FX with CTChip | Detection of single CTC/3.75 mL blood samples | p-value indicated that the results were not statistically significant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chrzempiec, M.; Oleksiewicz, U. Circulating Tumor Cells for the Monitoring of Lung Cancer Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010384

Chrzempiec M, Oleksiewicz U. Circulating Tumor Cells for the Monitoring of Lung Cancer Therapies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010384

Chicago/Turabian StyleChrzempiec, Maja, and Urszula Oleksiewicz. 2026. "Circulating Tumor Cells for the Monitoring of Lung Cancer Therapies" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010384

APA StyleChrzempiec, M., & Oleksiewicz, U. (2026). Circulating Tumor Cells for the Monitoring of Lung Cancer Therapies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010384