Detection and Characterization of the Eukaryotic Vacant Ribosome

Abstract

1. Introduction

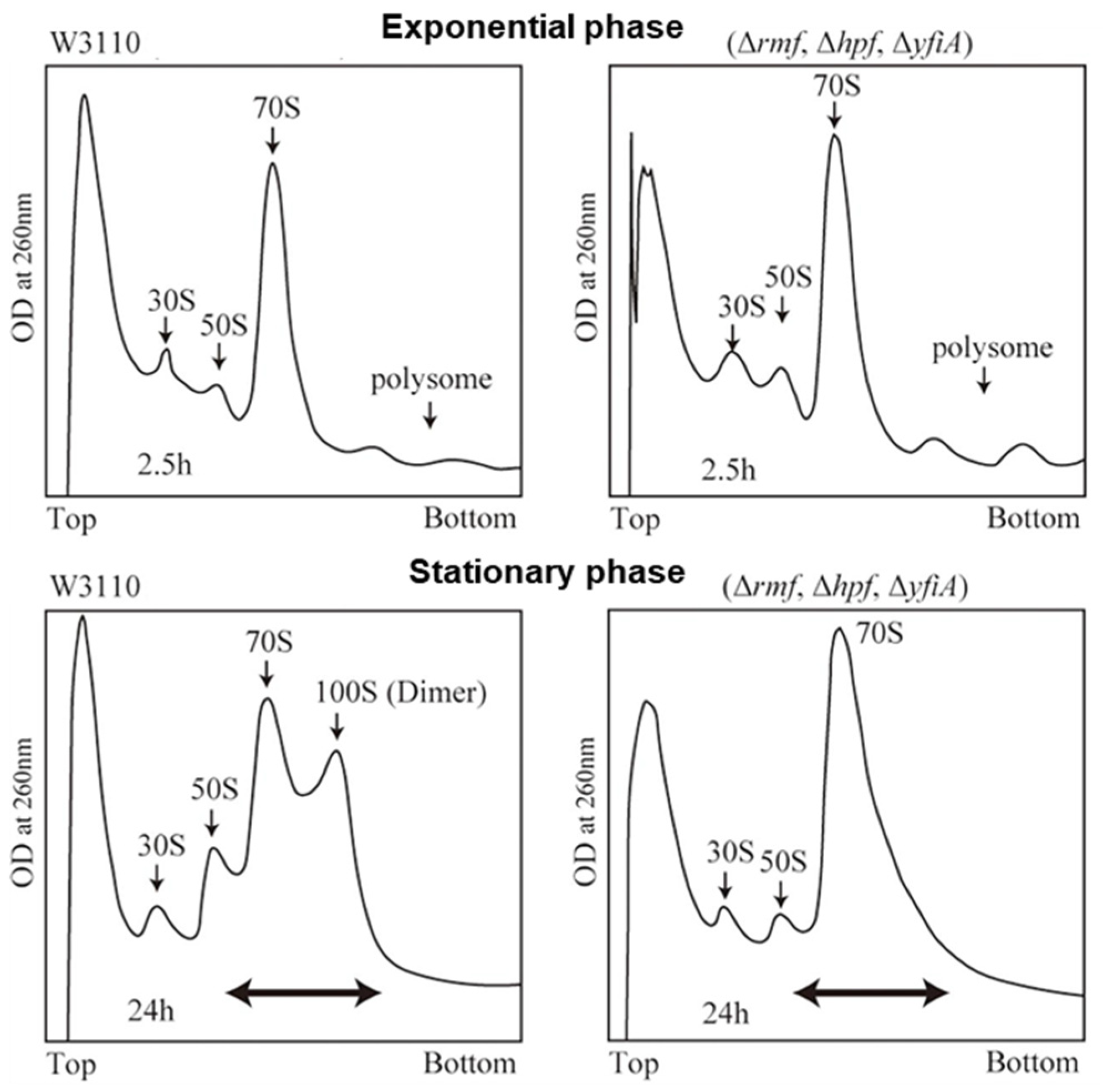

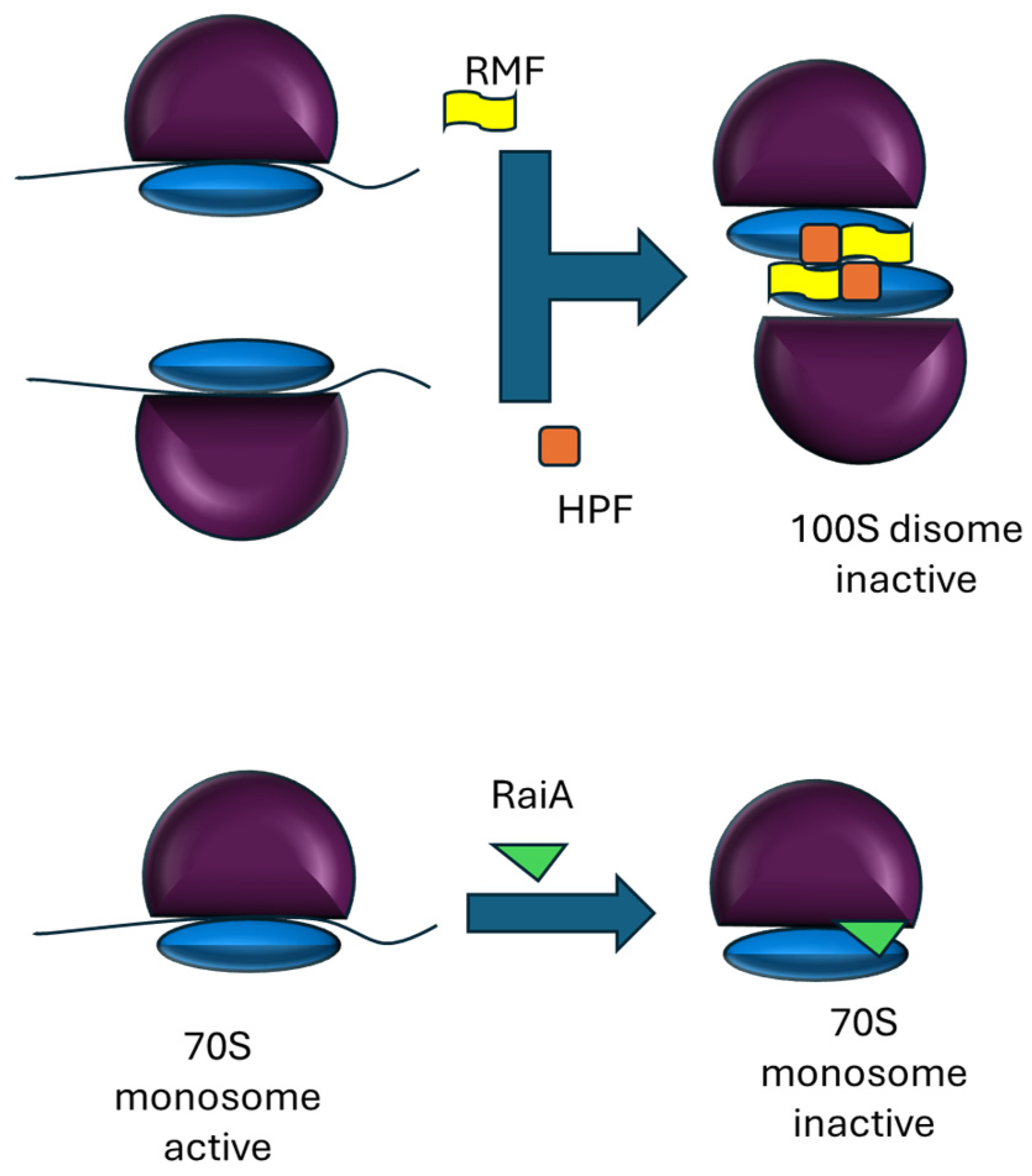

2. Dormant Ribosomes in Prokaryotes and Plant Chloroplasts

3. From Bacteria to Eukaryotes: Challenges to Identifying Vacant Ribosomes

3.1. Protein Interactions with Dormant Ribosomes in Yeast

| Year | Authors (First/Last) | Finding | Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | Van Dyke/Van Dyke [28] | Stm1 associates with ribosomes independently of mRNA; stm1Δ cells show reduced viability under prolonged nitrogen starvation. | Long-term nitrogen starvation (2 to 6 days). |

| 2011 | Balagopal/Parker [30] | Stm1 overexpression causes stronger growth inhibition in dom34Δ strains than in wild type, suggesting that Stm1 stalls ribosomes in vivo and that Dom34/Hbs1 releases Stm1-stalled ribosomes. | Growth on rich medium under mild cold shock (16 °C). |

| 2011 | Ben-Shem/Yusupov [29] | Crystal structure reveals only one non-ribosomal protein, Stm1. Stm1 is suggested to clamp the two subunits preventing their dissociation, and inhibiting translation by excluding mRNA binding. | Short-term glucose starvation (30 °C, 10 min). |

| 2013 | Van Dyke/Van Dyke [17] | Ribosomal protein levels are similar in wild-type and stm1Δ cells after one day in quiescence but diverge after four days; Stm1 overexpression prevents ribosome degradation. | Long-term starvation: stationary phase (4 days). |

| 2014 | van den Elzen/Séraphin [31] | Stm1-bound 80S ribosomes are substrates for Dom34/Hbs1/Rli1-mediated subunit splitting in vitro. Deletion of STM1 suppresses the requirement for Dom34-Hbs1 to restart translation in vivo. | Short-term glucose starvation combined with mild cold shock (10 min, 16 °C). |

| Year | Authors (First/Last) | Finding | Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | Wang/Gilbert [32] | Lso2 shows increased association with ribosomes upon starvation; recovery from starvation is accelerated in the presence of Lso2, as indicated by earlier reappearance of polysomes. | Short term glucose starvation (2 h). |

| 2020 | Wells/Beckmann [33] | Cryo-EM analysis identifies two distinct populations of idle, translationally repressed 80S ribosomes: one bound to Stm1/SERBP1 together with eEF2, and the other bound to Lso2 (CCDC124). These populations differ in both composition and ribosome conformation. | Human embryonic kidney ([HEK]293T) cells at high confluency. |

3.2. Dimeric Hibernating Ribosomes in Eukaryotes?

3.3. Vacant Monosomes in Mammals

3.4. Neurons: Active Monosomes and Dormant Polysomes?

| Method | Interpretation and Limitations | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallography; cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) | Crystallography provides high-resolution structural information, whereas cryo-EM enables the identification of distinct ribosome populations with different compositions, factor occupancy, and tRNA binding states. | [29,51] |

| Effect of potassium chloride (KCl) on polysome profiles | Actively translating polysomes are largely resistant to elevated KCl concentrations, whereas vacant monosomes dissociate into subunits. However, a subset of vacant monosomes exhibits intermediate KCl resistance, limiting the specificity of this assay. | [31,51] |

| Ribosome-to-mRNA stoichiometry | Relative ribosome numbers per mRNA can be estimated by quantifying rRNA using gel staining, qPCR, or RNA-seq after filtering anomalously amplified rRNA species, providing a relative measure of ribosome vacancy. | [15,32] |

| Functional characterization | Hibernation: protection of ribosomes from degradation. Enhanced recovery of translation: ribosome splitting. | [17,32] |

4. Methodological Challenges in Quantifying Ribosome Dormancy

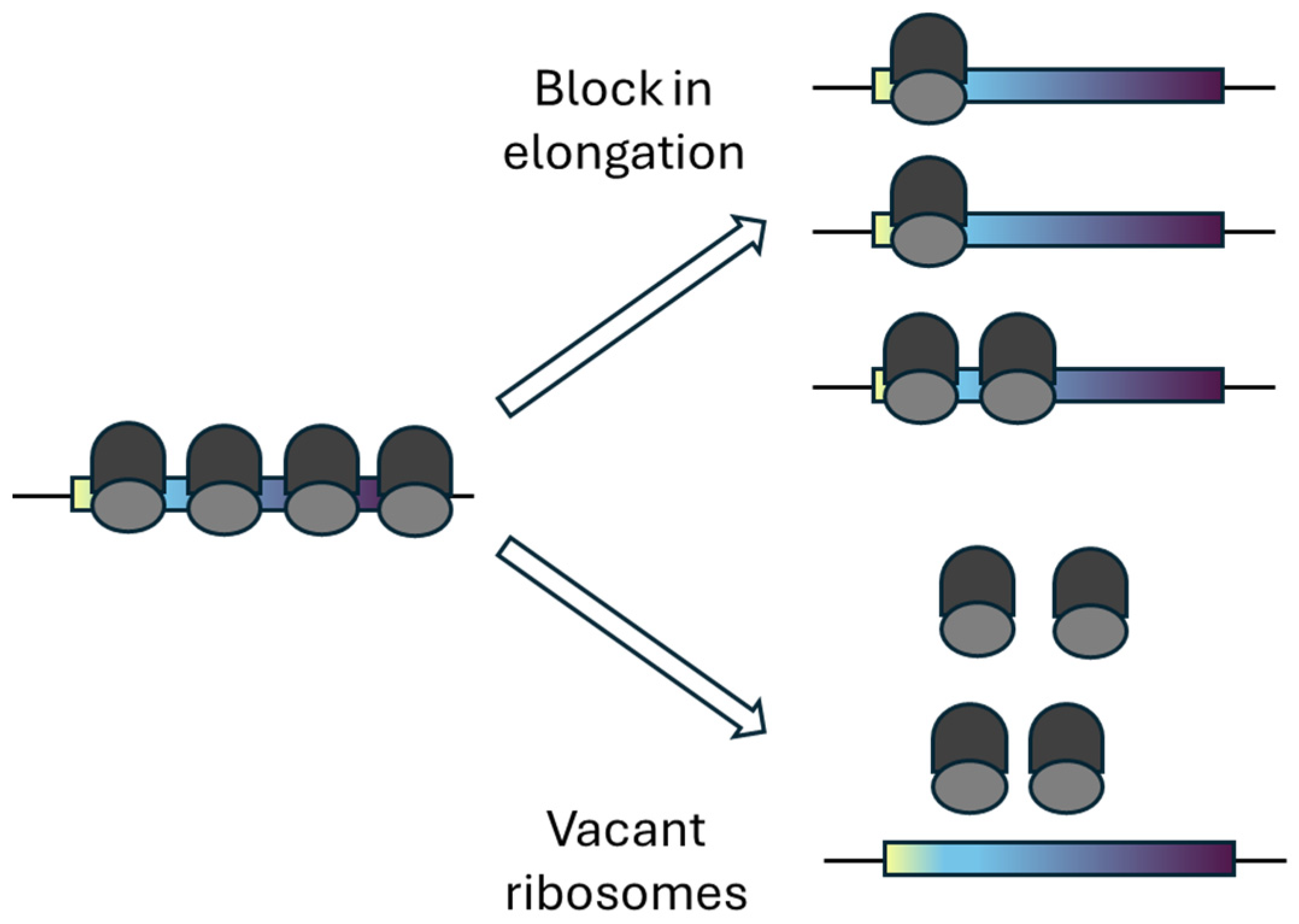

4.1. Distinguishing Vacant Ribosomes from Elongation Blockade

4.2. Distinguishing Hibernating Dimers from Collided Ribosomes

4.3. Quantifying Post-Transcriptional Processes During Stress

4.4. Stress-Induced Changes in Cytoplasmic Biophysical Properties

5. Biological and Biotechnological Relevance of Dormant and Inactive Ribosomes

6. Summary and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gregory, B.; Rahman, N.; Bommakanti, A.; Shamsuzzaman, M.; Thapa, M.; Lescure, A.; Zengel, J.M.; Lindahl, L. The small and large ribosomal subunits depend on each other for stability and accumulation. Life Sci. Alliance 2019, 2, e201800150, Erratum in Life Sci. Alliance 2019, 2, e201900508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.R.; Pandit, S.C.; Loerch, S.; Campbell, Z.T. The space between notes: Emerging roles for translationally silent ribosomes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2022, 47, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piir, K.; Paier, A.; Liiv, A.; Tenson, T.; Maivali, U. Ribosome degradation in growing bacteria. EMBO Rep. 2011, 12, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyant, G.A.; Abu-Remaileh, M.; Frenkel, E.M.; Laqtom, N.N.; Dharamdasani, V.; Lewis, C.A.; Chan, S.H.; Heinze, I.; Ori, A.; Sabatini, D.M. NUFIP1 is a ribosome receptor for starvation-induced ribophagy. Science 2018, 360, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prossliner, T.; Skovbo Winther, K.; Sorensen, M.A.; Gerdes, K. Ribosome Hibernation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2018, 52, 321–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prossliner, T.; Gerdes, K.; Sorensen, M.A.; Winther, K.S. Hibernation factors directly block ribonucleases from entering the ribosome in response to starvation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 2226–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, H.; Nakayama, H.; Maki, Y.; Ueta, M.; Wada, C.; Wada, A. Functional Sites of Ribosome Modulation Factor (RMF) Involved in the Formation of 100S Ribosome. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 661691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, H.; Wada, A. The 100S ribosome: Ribosomal hibernation induced by stress. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2014, 5, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, A.; Yamazaki, Y.; Fujita, N.; Ishihama, A. Structure and probable genetic location of a “ribosome modulation factor” associated with 100S ribosomes in stationary-phase Escherichia coli cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 2657–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koli, S.; Shetty, S. Ribosomal dormancy at the nexus of ribosome homeostasis and protein synthesis. BioEssays 2024, 46, e2300247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Krin, E.; Korlowski, C.; Sismeiro, O.; Varet, H.; Coppee, J.Y.; Mazel, D.; Baharoglu, Z. Sleeping ribosomes: Bacterial signaling triggers RaiA mediated persistence to aminoglycosides. iScience 2021, 24, 103128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, K.; Yoshizawa, Y.; Oda, T.; Sekine, Y. Chloroplast Hibernation-Promoting Factor PSRP1 Prevents Ribosome Degradation Under Darkness Independently of 100S Dimer Formation. Plants 2025, 14, 3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krokowski, D.; Gaccioli, F.; Majumder, M.; Mullins, M.R.; Yuan, C.L.; Papadopoulou, B.; Merrick, W.C.; Komar, A.A.; Taylor, D.; Hatzoglou, M. Characterization of hibernating ribosomes in mammalian cells. Cell Cycle 2011, 10, 2691–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaren, M.; Conners, R.; Isupov, M.N.; Gil-Diez, P.; Gambelli, L.; Gold, V.A.M.; Walter, A.; Connell, S.R.; Williams, B.; Daum, B. CryoEM reveals that ribosomes in microsporidian spores are locked in a dimeric hibernating state. Nat. Microbiol. 2023, 8, 1834–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, S.; Schiffelholz, N.; Mittal, N.; Frohlich, K.E.; Zavolan, M.; Becskei, A. Heat shock induces silent ribosomes and reorganizes mRNA turnover. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 116447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, Y.; Yoshida, H.; Wada, A. Two proteins, YfiA and YhbH, associated with resting ribosomes in stationary phase Escherichia coli. Genes Cells 2000, 5, 965–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyke, N.; Chanchorn, E.; Van Dyke, M.W. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein Stm1p facilitates ribosome preservation during quiescence. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 430, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.H.; Li, Z.; Park, J.O.; King, C.G.; Rabinowitz, J.D.; Wingreen, N.S.; Gitai, Z. Escherichia coli translation strategies differ across carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus limitation conditions. Nat. Microbiol. 2018, 3, 939–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S.; Cherkasova, V.; Bankhead, P.; Bukau, B.; Stoecklin, G. Translation suppression promotes stress granule formation and cell survival in response to cold shock. Mol. Biol. Cell 2012, 23, 3786–3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Lomeli, M.; Morais, B.L.; Figueiredo, D.L.; Neto, D.C.; Martins, J.R.; Masuda, C.A. The initiation factor eIF4A is involved in the response to lithium stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 21542–21548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresno, M.; Jimenez, A.; Vazquez, D. Inhibition of translation in eukaryotic systems by harringtonine. Eur. J. Biochem. 1977, 72, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalgi, R.; Hurt, J.A.; Krykbaeva, I.; Taipale, M.; Lindquist, S.; Burge, C.B. Widespread Regulation of Translation by Elongation Pausing in Heat Shock. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Han, Y.; Qian, S.B. Cotranslational response to proteotoxic stress by elongation pausing of ribosomes. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, G.C.; Guerrero, S.; Silva, G.M. The central role of translation elongation in response to stress. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2023, 51, 959–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, I.C.; Tuorto, F.; Jordan, D.; Legrand, C.; Price, J.; Braukmann, F.; Hendrick, A.G.; Akay, A.; Kotter, A.; Helm, M.; et al. Translational adaptation to heat stress is mediated by RNA 5-methylcytosine in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J. 2021, 40, e105496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, A.; Belardinelli, R.; Maracci, C.; Milon, P.; Rodnina, M.V. Directional transition from initiation to elongation in bacterial translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 10700–10712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Johnson, A.G.; Lapointe, C.P.; Choi, J.; Prabhakar, A.; Chen, D.H.; Petrov, A.N.; Puglisi, J.D. eIF5B gates the transition from translation initiation to elongation. Nature 2019, 573, 605–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyke, N.; Baby, J.; Van Dyke, M.W. Stm1p, a ribosome-associated protein, is important for protein synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae under nutritional stress conditions. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 358, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Shem, A.; Garreau de Loubresse, N.; Melnikov, S.; Jenner, L.; Yusupova, G.; Yusupov, M. The structure of the eukaryotic ribosome at 3.0 A resolution. Science 2011, 334, 1524–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balagopal, V.; Parker, R. Stm1 modulates translation after 80S formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. RNA 2011, 17, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Elzen, A.M.; Schuller, A.; Green, R.; Seraphin, B. Dom34-Hbs1 mediated dissociation of inactive 80S ribosomes promotes restart of translation after stress. EMBO J. 2014, 33, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Vaidyanathan, P.P.; Rojas-Duran, M.F.; Udeshi, N.D.; Bartoli, K.M.; Carr, S.A.; Gilbert, W.V. Lso2 is a conserved ribosome-bound protein required for translational recovery in yeast. PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, e2005903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.N.; Buschauer, R.; Mackens-Kiani, T.; Best, K.; Kratzat, H.; Berninghausen, O.; Becker, T.; Gilbert, W.; Cheng, J.; Beckmann, R. Structure and function of yeast Lso2 and human CCDC124 bound to hibernating ribosomes. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemin, O.; Gluc, M.; Rosa, H.; Purdy, M.; Niemann, M.; Peskova, Y.; Mattei, S.; Jomaa, A. Ribosomes hibernate on mitochondria during cellular stress. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M.J.; Roy, S.; Archuletta, A.B.; Wentzell, P.D.; Anna-Arriola, S.S.; Rodriguez, A.L.; Aragon, A.D.; Quinones, G.A.; Allen, C.; Werner-Washburne, M. Genomic analysis of stationary-phase and exit in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Gene expression and identification of novel essential genes. Mol. Biol. Cell 2004, 15, 5295–5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naranjo-Ortiz, M.A.; Gabaldon, T. Fungal evolution: Diversity, taxonomy and phylogeny of the Fungi. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2019, 94, 2101–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Chen, J.; Lv, Q.; Long, M.; Pan, G.; Zhou, Z. Germination of Microsporidian Spores: The Known and Unknown. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, A.; Zhou, C.; Weber, C.C.; Vancaester, E.; Sims, Y.; Makunin, A.; Mathers, T.C.; Absolon, D.E.; Wood, J.M.D.; McCarthy, S.A.; et al. Forty new genomes shed light on sexual reproduction and the origin of tetraploidy in Microsporidia. PLoS Biol. 2025, 23, e3003446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anger, A.M.; Armache, J.P.; Berninghausen, O.; Habeck, M.; Subklewe, M.; Wilson, D.N.; Beckmann, R. Structures of the human and Drosophila 80S ribosome. Nature 2013, 497, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, S.; Hofstetter, J.; Battaglioni, S.; Ritz, D.; Hall, M.N. TORC1 phosphorylates and inhibits the ribosome preservation factor Stm1 to activate dormant ribosomes. EMBO J. 2023, 42, e112344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuvalova, E.; Egorova, T.; Ivanov, A.; Shuvalov, A.; Biziaev, N.; Mukba, S.; Pustogarov, N.; Terenin, I.; Alkalaeva, E. Discovery of a novel role of tumor suppressor PDCD4 in stimulation of translation termination. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 101269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito Querido, J.; Sokabe, M.; Diaz-Lopez, I.; Gordiyenko, Y.; Zuber, P.; Du, Y.; Albacete-Albacete, L.; Ramakrishnan, V.; Fraser, C.S. Human tumor suppressor protein Pdcd4 binds at the mRNA entry channel in the 40S small ribosomal subunit. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Huang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Meng, W.; Miao, M.; Cheng, J. Human tumor suppressor PDCD4 directly interacts with ribosomes to repress translation. Cell Res. 2024, 34, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Paolo, A.; Eastman, G.; Mesquita-Ribeiro, R.; Farias, J.; Macklin, A.; Kislinger, T.; Colburn, N.; Munroe, D.; Sotelo Sosa, J.R.; Dajas-Bailador, F.; et al. PDCD4 regulates axonal growth by translational repression of neurite growth-related genes and is modulated during nerve injury responses. RNA 2020, 26, 1637–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranu, R.S. Inhibition of eukaryotic protein chain initiation by vanadate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1983, 80, 3148–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, A.; Dolan, B.P.; Hickman, H.D.; Knowlton, J.J.; Clavarino, G.; Pierre, P.; Bennink, J.R.; Yewdell, J.W. Nuclear translation visualized by ribosome-bound nascent chain puromycylation. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 197, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussey, G.S.; Link, L.A.; Brown, A.S.; Howley, B.V.; Chaudhury, A.; Howe, P.H. Establishment of a TGFbeta-induced post-transcriptional EMT gene signature. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krichevsky, A.M.; Kosik, K.S. Neuronal RNA granules: A link between RNA localization and stimulation-dependent translation. Neuron 2001, 32, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soudet, J.; Gelugne, J.P.; Belhabich-Baumas, K.; Caizergues-Ferrer, M.; Mougin, A. Immature small ribosomal subunits can engage in translation initiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 2010, 29, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biever, A.; Glock, C.; Tushev, G.; Ciirdaeva, E.; Dalmay, T.; Langer, J.D.; Schuman, E.M. Monosomes actively translate synaptic mRNAs in neuronal processes. Science 2020, 367, eaay4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blandy, A.; Hopes, T.; Vasconcelos, E.J.R.; Turner, A.; Fatkhullin, B.; Agapiou, M.; Fontana, J.; Aspden, J.L. Translational activity of 80S monosomes varies dramatically across different tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, gkaf292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zylber, E.A.; Penman, S. The effect of high ionic strength on monomers, polyribosomes, and puromycin-treated polyribosomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1970, 204, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.E.; Hartwell, L.H. Resistance of active yeast ribosomes to dissociation by KCl. J. Biol. Chem. 1970, 245, 1504–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Becskei, A. Gene choice in cancer cells is exclusive in ion transport but concurrent in DNA replication. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 23, 2534–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popper, B.; Burkle, M.; Ciccopiedi, G.; Marchioretto, M.; Forne, I.; Imhof, A.; Straub, T.; Viero, G.; Gotz, M.; Schieweck, R. Ribosome inactivation regulates translation elongation in neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 105648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, S.; Allan, K.C.; Pinkard, O.; Sweet, T.; Tesar, P.J.; Coller, J. Oligodendrocyte differentiation alters tRNA modifications and codon optimality-mediated mRNA decay. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidibe, H.; Vande Velde, C. RNA Granules and Their Role in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1203, 195–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anadolu, M.N.; Sun, J.; Li, J.T.; Graber, T.E.; Ortega, J.; Sossin, W.S. Puromycin reveals a distinct conformation of neuronal ribosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2306993121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blobel, G.; Sabatini, D. Dissociation of mammalian polyribosomes into subunits by puromycin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1971, 68, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Qian, S.B. Characterizing inactive ribosomes in translational profiling. Translation 2016, 4, e1138018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomuro, K.; Mito, M.; Toh, H.; Kawamoto, N.; Miyake, T.; Chow, S.Y.A.; Doi, M.; Ikeuchi, Y.; Shichino, Y.; Iwasaki, S. Calibrated ribosome profiling assesses the dynamics of ribosomal flux on transcripts. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helena-Bueno, K.; Rybak, M.Y.; Ekemezie, C.L.; Sullivan, R.; Brown, C.R.; Dingwall, C.; Basle, A.; Schneider, C.; Connolly, J.P.R.; Blaza, J.N.; et al. A new family of bacterial ribosome hibernation factors. Nature 2024, 626, 1125–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, L.I.; Omae, K.; Brown, C.R.; Amikura, K.; Ekemezie, C.L.; Clark, J.; Nishide, K.; Helena-Bueno, K.; Palmowski, P.; Porter, A.; et al. The evolutionary lifecycle of ribosome hibernation factors. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Chen, Y.M.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Gao, N.; Qian, W. Disome-seq reveals widespread ribosome collisions that promote cotranslational protein folding. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar Rangel, M.; Stein, K.; Frydman, J. A machine learning approach uncovers principles and determinants of eukaryotic ribosome pausing. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eado0738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, L.D.; Moura, A.P.S.; Ciandrini, L. Gene length as a regulator for ribosome recruitment and protein synthesis: Theoretical insights. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, S.; Faravelli, S.; Voegeli, S.; Becskei, A. Polysome propensity and tunable thresholds in coding sequence length enable differential mRNA stability. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadh9545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, Y.; Tesina, P.; Nakajima, S.; Mizuno, M.; Endo, A.; Buschauer, R.; Cheng, J.; Shounai, O.; Ikeuchi, K.; Saeki, Y.; et al. RQT complex dissociates ribosomes collided on endogenous RQC substrate SDD1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishibashi, K.; Shichino, Y.; Han, P.; Wakabayashi, K.; Mito, M.; Inada, T.; Kimura, S.; Iwasaki, S.; Mishima, Y. Translation of zinc finger domains induces ribosome collision and Znf598-dependent mRNA decay in zebrafish. PLoS Biol. 2024, 22, e3002887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meydan, S.; Guydosh, N.R. A cellular handbook for collided ribosomes: Surveillance pathways and collision types. Curr. Genet. 2021, 67, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, A.M.; Nair, N.U. Specific codons control cellular resources and fitness. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaquet, V.; Wallerich, S.; Voegeli, S.; Turos, D.; Viloria, E.C.; Becskei, A. Determinants of the temperature adaptation of mRNA degradation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 1092–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becskei, A.; Rahaman, S. The life and death of RNA across temperatures. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 4325–4336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, H.; Utsumi, D.; Torihara, H.; Takahashi, K.; Kuroyanagi, H.; Yamashita, A. Simultaneous measurement of nascent transcriptome and translatome using 4-thiouridine metabolic RNA labeling and translating ribosome affinity purification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, D.A.; Bahler, J.; Wise, J.A. Schizosaccharomyces pombe Polysome Profile Analysis and RNA Purification. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2017, 2017, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, D.A.; Shi, L.; Tu, B.P.; Weissman, J.S. Cycloheximide can distort measurements of mRNA levels and translation efficiency. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 4974–4985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraenkel, D.G. Yeast Intermediary Metabolism; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Woodbury, NY, USA, 2011; p. ix. 434p. [Google Scholar]

- Reier, K.; Liiv, A.; Remme, J. Ribosome Protein Composition Mediates Translation during the Escherichia coli Stationary Phase. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Brar, G.A. Global translation inhibition yields condition-dependent de-repression of ribosome biogenesis mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 5061–5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Tong, M.; Suttapitugsakul, S.; Xu, S.; Wu, R. Global quantification of newly synthesized proteins reveals cell type- and inhibitor-specific effects on protein synthesis inhibition. PNAS Nexus 2023, 2, pgad168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Shu, T.; Liu, T.; Spindler, M.C.; Mahamid, J.; Hocky, G.M.; Gresham, D.; Holt, L.J. Polysome collapse and RNA condensation fluidize the cytoplasm. Mol. Cell 2024, 84, 2698–2716.E9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Meng, L.; Liao, Z.; Ji, W.; Zhang, P.; Lin, J.; Guo, Q. Translation landscape of stress granules. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eady6859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorovskiy, A.G.; Burakov, A.V.; Terenin, I.M.; Bykov, D.A.; Lashkevich, K.A.; Popenko, V.I.; Makarova, N.E.; Sorokin, I.I.; Sukhinina, A.P.; Prassolov, V.S.; et al. A Solitary Stalled 80S Ribosome Prevents mRNA Recruitment to Stress Granules. Biochemistry 2023, 88, 1786–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodiazhenko, T.; Johansson, M.J.O.; Takada, H.; Nissan, T.; Hauryliuk, V.; Murina, V. Elimination of Ribosome Inactivating Factors Improves the Efficiency of Bacillus subtilis and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cell-Free Translation Systems. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekemezie, C.L.; Melnikov, S.V. Hibernating ribosomes as drug targets? Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1436579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshan, P.; Biswas, A.; Ahmed, S.; Anagnos, S.; Luebbers, R.; Harish, K.; Li, M.; Nguyen, N.; Zhou, G.; Tedeschi, F.; et al. Sequestration of ribosomal subunits as inactive 80S by targeting eIF6 limits mitotic exit and cancer progression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, gkae1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Delaney, C.E.; Becskei, A. Detection and Characterization of the Eukaryotic Vacant Ribosome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 308. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010308

Delaney CE, Becskei A. Detection and Characterization of the Eukaryotic Vacant Ribosome. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):308. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010308

Chicago/Turabian StyleDelaney, Colin E., and Attila Becskei. 2026. "Detection and Characterization of the Eukaryotic Vacant Ribosome" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 308. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010308

APA StyleDelaney, C. E., & Becskei, A. (2026). Detection and Characterization of the Eukaryotic Vacant Ribosome. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 308. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010308