Effects of Carvacrol on Oxidative Stress and Fibrosis in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Nephropathy: Histological, Gene Expression, and Biochemical Insights

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Biochemical Analysis

2.2. Histopathological Analysis

2.3. IHC Analysis

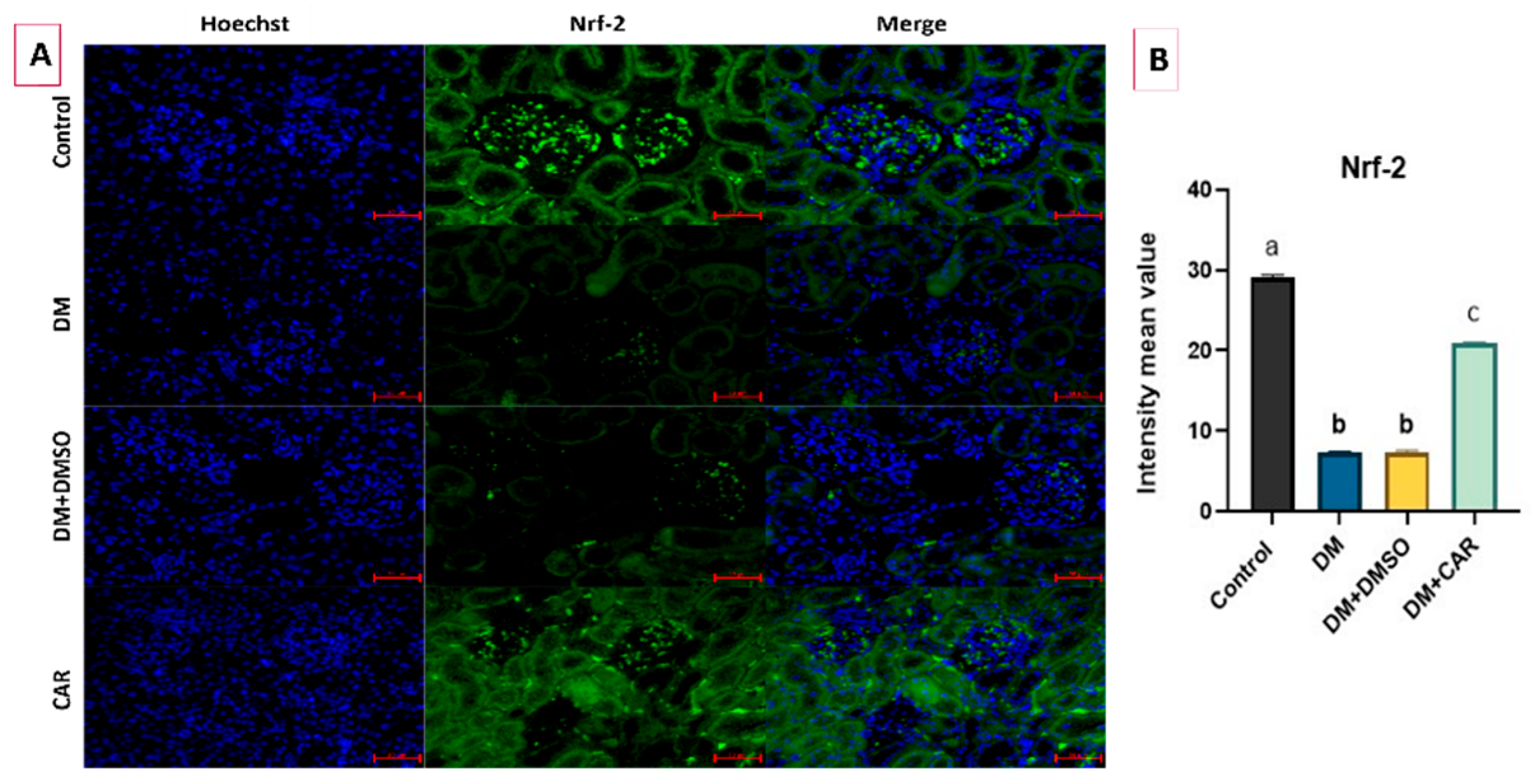

2.4. IF Analysis

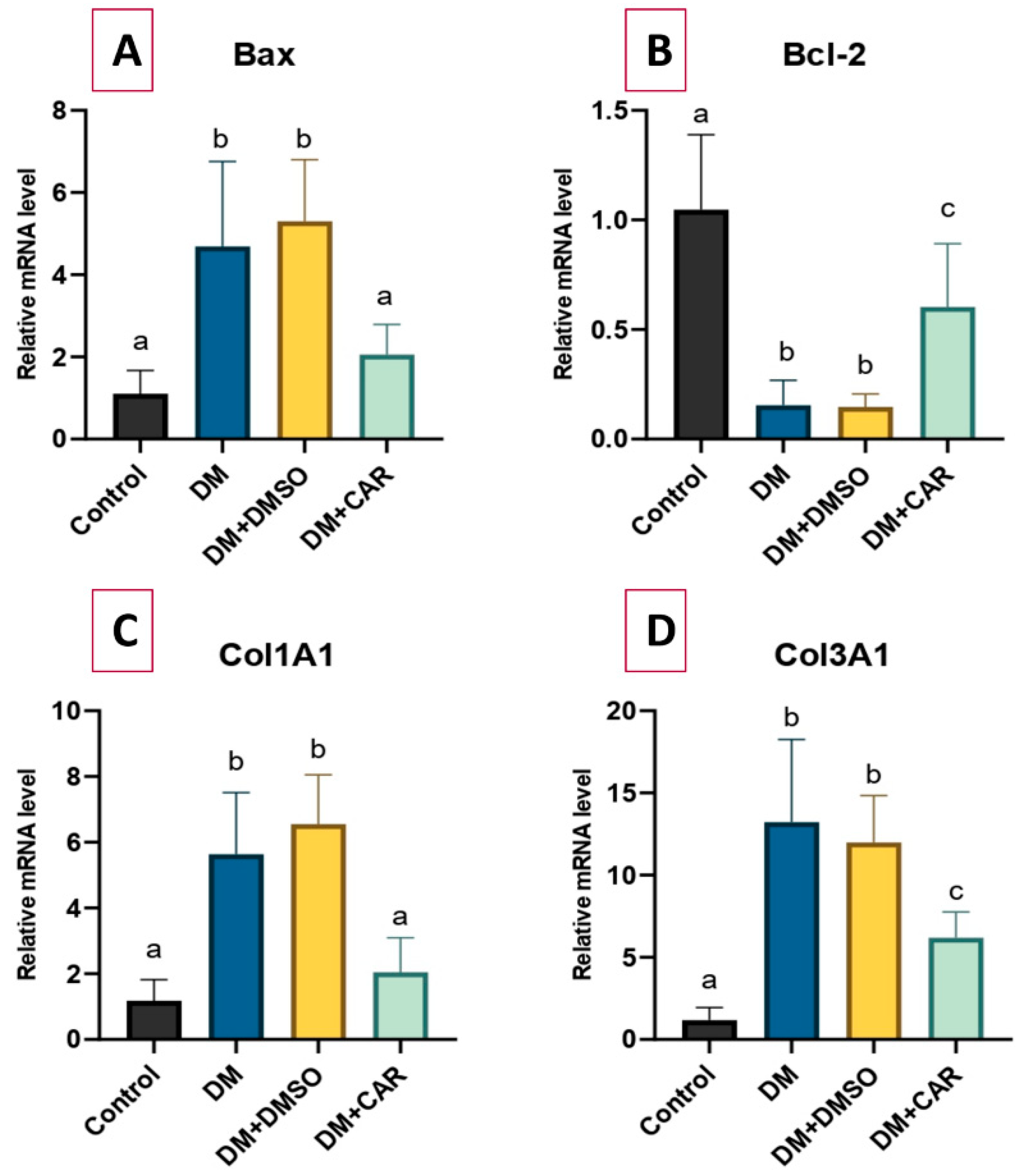

2.5. RT-qPCR Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals and Experimental Groups

4.2. Biochemical Analysis

4.3. Histopathological Analysis

4.4. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Analysis

4.5. Immunofluorescence (IF) Analysis

4.6. RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis, and Gene Expression Analysis by RT-qPCR

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jin, Q.; Liu, T.; Qiao, Y.; Liu, D.; Yang, L.; Mao, H.; Ma, F.; Wang, Y.; Peng, L.; Zhan, Y. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Diabetic Nephropathy: Role of Polyphenols. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1185317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, B.; Suleyman, B.; Mammadov, R.; Gezer, A.; Mendil, A.S.; Akbas, N.; Bulut, S.; Dal, C.N.; Suleyman, H. The Effect of Carvacrol upon Experimentally Induced Diabetic Neuropathy and Neuropathic Pain in Rats. Acta Pol. Pharm. Drug Res. 2022, 79, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darenskaya, M.; Kolesnikov, S.; Semenova, N.; Kolesnikova, L. Diabetic Nephropathy: Significance of Determining Oxidative Stress and Opportunities for Antioxidant Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, S.; Sikarwar, M.S. Diabetic Nephropathy: Pathogenesis, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Strategies. Horm Metab Res. 2025, 57, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Lu, L.; Hou, W.; Huang, T.; Chen, X.; Qi, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, M. Epigenetics in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2022, 54, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, H.R.; Zeinabady, Z.; Zamani, E.; Shokrzadeh, M.; Shaki, F. Attenuation of Diabetic Nephropathy by Carvacrol through Anti-Oxidative Effects in Alloxan-Induced Diabetic Rats. Res. J. Pharmacogn. 2018, 5, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Aslam, M.; Alsagaby, S.A.; Saeed, F.; Ahmad, I.; Afzaal, M.; Arshad, M.U.; Abdelgawad, M.A.; El-Ghorab, A.H.; Khames, A.; et al. Therapeutic Application of Carvacrol: A Comprehensive Review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 3544–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassiliou, E.; Awoleye, O.; Davis, A.; Mishra, S. Anti-Inflammatory and Antimicrobial Properties of Thyme Oil and Its Main Constituents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, A.; Przychodna, M.; Sopata, S.; Bodalska, A.; Fecka, I. Thymol and Thyme Essential Oil-New Insights into Selected Therapeutic Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, M.F.; Durço, A.O.; Rabelo, T.K.; Barreto, R.S.S.; Guimarães, A.G. Effects of Carvacrol, Thymol and essential oils containing such monoterpenes on wound healing: A systematic review. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2019, 71, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mai, Y.; Qiu, X.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Yuan, W.; Hou, N. Effect of Long-Term Treatment of Carvacrol on Glucose Metabolism in Streptozotocin induced Diabetic Mice. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoca, M.; Becer, E.; Vatansever, H.S. Carvacrol is potential molecule for diabetes treatment. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 130, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanase, D.M.; Gosav, E.M.; Anton, M.I.; Floria, M.; Seritean Isac, P.N.; Hurjui, L.L.; Tarniceriu, C.C.; Costea, C.F.; Ciocoiu, M.; Rezus, C. Oxidative Stress and NRF2/KEAP1/ARE Pathway in Diabetic Kidney Disease (DKD): New Perspectives. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, L.F.; Eguchi, N.; Whaley, D.; Alexander, M.; Tantisattamo, E.; Ichii, H. Anti-Oxidative Therapy in Diabetic Nephropathy. Front. Biosci. Sch. 2022, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayramoglu, G.; Senturk, H.; Bayramoglu, A.; Uyanoglu, M.; Colak, S.; Ozmen, A.; Kolankaya, D. Carvacrol Partially Reverses Symptoms of Diabetes in STZ-Induced Diabetic Rats. Cytotechnology 2014, 66, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohany, M.; Ahmed, M.M.; Al-Rejaie, S.S. The Role of NF-κB and Bax/Bcl-2/Caspase-3 Signaling Pathways in the Protective Effects of Sacubitril/Valsartan (Entresto) against HFD/STZ-Induced Diabetic Kidney Disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahab, N.A.A.; Giribabu, N.; Kilari, E.K.; Salleh, N. Abietic Acid Ameliorates Nephropathy Progression via Mitigating Renal Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, Fibrosis and Apoptosis in High Fat Diet and Low Dose Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Phytomedicine 2022, 107, 154464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayan, D.; Şeneş, M.; Çaycı, A.B.; Söylemez, S.; Eren, N.; Altuntaş, Y.; Öztürk, F.Y. Evaluation of Paraoxonase, Arylesterase, and Homocysteine Thiolactonase Activities in Patients with Diabetes and Incipient Diabetes Nephropathy. J. Med. Biochem. 2019, 38, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.W.; Yang, M.Y.; Hung, T.W.; Chang, Y.C.; Wang, C.J. Nelumbo Nucifera Leaves Extract Attenuate the Pathological Progression of Diabetic Nephropathy in High-Fat Diet-Fed and Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. J. Food Drug Anal. 2019, 27, 736–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.J.; Kong, L.; Tang, Z.Z.; Zhang, Y.M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, T.Y.; Liu, Y.W. Hesperetin Ameliorates Diabetic Nephropathy in Rats by Activating Nrf2/ARE/Glyoxalase 1 Pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 111, 1166–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, M.S.; Upasani, C.D.; Upaganlawar, A.B.; Gulecha, V.S. Renoprotective Effect of Co-Enzyme Q10 and N-Acetylcysteine on Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Nephropathy in Rats. Int. J. Diabetes Clin. Res. 2020, 2020, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canbaz, F.A.; Yurtçu, M.; Oltulu, P.; Taştekin, G.; Kocabaş, R.; Doğan, M. Investigation of the Effects of N-Acetylcysteine and Selenium on Vesicoureteral Reflux Nephropathy: An Experimental Study. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2024, 59, 161616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Qu, H.; Niu, X.; Li, T.; Wang, L.; Peng, H. Carvacrol Improves Blood Lipid and Glucose in Rats with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus by Regulating Short-Chain Fatty Acids and the GPR41/43 Pathway. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2024, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, Q.; Zhao, D.; Lian, F.; Li, X.; Qi, W. The Impact of Oxidative Stress-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction on Diabetic Microvascular Complications. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1112363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.H.; Sabbaghi, A.; Carroll, C.C. Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes Alters Transcription of Multiple Genes Necessary for Extracellular Matrix Remodeling in Rat Patellar Tendon. Connect. Tissue Res. 2018, 59, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, X.; Shen, E.; Wang, X.; Hu, B. Differentially Expressed MicroRNAs and Their Target Genes in the Hearts of Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Mice. Mol. Med. Rep. 2011, 4, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Azab, E.F.; Mostafa, H.S. Geraniol Ameliorates the Progression of High Fat-Diet/Streptozotocin-Induced Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Rats via Regulation of Caspase-3, Bcl-2, and Bax Expression. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Li, J.; Wei, H.; Liang, Z. Maackiain Protects the Kidneys of Type 2 Diabetic Rats via Modulating the Nrf2/Ho-1 and Tlr4/Nfκb/Caspase-3 Pathways. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2021, 15, 4339–4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Behl, T.; Sehgal, A.; Bhatia, S.; Jaglan, D.; Bungau, S. Therapeutic potential of Nrf-2 pathway in the treatment of diabetic neuropathy and nephropathy. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 2761–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, A.S. Kaempferol attenuates diabetic nephropathy in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats by a hypoglycaemic effect and concomitant activation of the Nrf-2/Ho-1/antioxidants axis. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 129, 984–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghloul, R.A.; Abdelghany, A.M.; Samra, Y.A. Rutin and selenium nanoparticles protected against STZ-induced diabetic nephropathy in rats through downregulating Jak-2/Stat3 pathway and upregulating Nrf-2/HO-1 pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 933, 175289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Qi, G.; Zhou, H.; Cheng, F.; Yang, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, R. Protective effect of thymol on glycerol-induced acute kidney injury. Ren. Fail. 2023, 45, 2227728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, S.; Pari, L. Protective effect of thymol on high fat diet induced diabetic nephropathy in C57BL/6J mice. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2016, 245, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peirovy, Y.; Asle-Rousta, M. Thymol and p-Cymene Protect the Liver by Mitigating Oxidative Stress, Suppressing TNF-α/NF-κB, and Enhancing Nrf2/HO-1 Expression in Immobilized Rats. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2024, 104, e14618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deepa, B.; Venkatraman Anuradha, C. Effects of linalool on inflammation, matrix accumulation and podocyte loss in kidney of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2013, 23, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Said, Y.A.M.; Sallam, N.A.A.; Ain-Shoka, A.A.; Abdel-Latif, H.A. Geraniol ameliorates diabetic nephropathy via interference with miRNA-21/PTEN/Akt/mTORC1 pathway in rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2020, 393, 2325–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cüce, G.; Sözen, M.E.; Çetinkaya, S.; Canbaz, H.T.; Seflek, H.; Kalkan, S. Effects of Nigella Sativa L. Seed Oil on Intima–Media Thickness and Bax and Caspase 3 Expression in Diabetic Rat Aorta. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2015, 16, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamli-Salino, S.E.J.; Brown, P.A.J.; Haschler, T.N.; Liang, L.; Feliers, D.; Wilson, H.M.; Delibegovic, M. Induction of experimental diabetes and diabetic nephropathy using anomer-equilibrated streptozotocin in male C57Bl/6J mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 650, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gültekin, B.; Çetinkaya Karabekir, S.; Ayan, I.Ç.; Savaş, H.B.; Cüce, G.; Kalkan, S.S. Effect of Carvacrol on Diabetes-Induced Oxidative Stress, Fibrosis and Apoptosis in Testicular Tissues of Adult Rats. Physiol. Res. 2025, 74, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckerson, H.W.; Wyte, C.M.; La Du, B.N. The Human Serum Paraoxonase/Arylesterase Polymorphism. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1983, 35, 1126–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Akın, F.; Yazar, A.; Türe, E.; Gültekin, Ü.; Kılıç, A.O.; Topçu, C.; Odabaş, D.; Yorulmaz, A. Paraoxonase-1 and Arylesterase Activities in Children with Acute Bronchiolitis. J. Contemp. Med. 2023, 13, 1064–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuce, G.; Cetinkaya, S.; Isitez, N.; Kuccukturk, S.; Sozen, M.E.; Kalkan, S.; Cigerci, I.H.; Demirel, H.H. Effects of Curcumin on Methyl Methanesulfonate Damage to Mouse Kidney. Biotech. Histochem. 2016, 91, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karabekir, S.C.; Gultekin, B.; Ayan, I.C.; Savas, H.B.; Cuce, G.; Kalkan, S. Protective Effect of Astaxanthin on Histopathologic Changes Induced by Bisphenol A in the Liver of Rats. Pak. Vet. J. 2024, 44, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Forward Primary (5′-3′) | Reverse Primary (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| BAX | GATGGCCTCCTTTCCTACTTC | CTTCTTCCAGATGGTGAGTGAG |

| BCL-2 | GGAGGATTGTGGCCTTCTTT | GTCATCCACAGAGCGATGTT |

| COL1A1 | CCAATGGTGCTCCTGGTATT | GTTCACCACTGTTGCCTTTG |

| COL3A1 | GTGTGATGATGAGCCACTAGAC | TGACAGGAGCAGGTGTAGAA |

| GAPDH | GCATTGCAGAGGATGGTAGAG | GCGGGAGAAGAAAGTCATGATTAG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Canbaz, H.T.; Sozen, M.E.; Cinar Ayan, I.; Savas, H.B.; Canbaz, F.A.; Cuce, G.; Kalkan, S. Effects of Carvacrol on Oxidative Stress and Fibrosis in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Nephropathy: Histological, Gene Expression, and Biochemical Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 291. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010291

Canbaz HT, Sozen ME, Cinar Ayan I, Savas HB, Canbaz FA, Cuce G, Kalkan S. Effects of Carvacrol on Oxidative Stress and Fibrosis in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Nephropathy: Histological, Gene Expression, and Biochemical Insights. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):291. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010291

Chicago/Turabian StyleCanbaz, Halime Tuba, Mehmet Enes Sozen, Ilknur Cinar Ayan, Hasan Basri Savas, Furkan Adem Canbaz, Gokhan Cuce, and Serpil Kalkan. 2026. "Effects of Carvacrol on Oxidative Stress and Fibrosis in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Nephropathy: Histological, Gene Expression, and Biochemical Insights" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 291. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010291

APA StyleCanbaz, H. T., Sozen, M. E., Cinar Ayan, I., Savas, H. B., Canbaz, F. A., Cuce, G., & Kalkan, S. (2026). Effects of Carvacrol on Oxidative Stress and Fibrosis in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Nephropathy: Histological, Gene Expression, and Biochemical Insights. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 291. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010291