Genetic Characterisation of Closely Related Lactococcus lactis Strains Used in Dairy Starter Cultures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

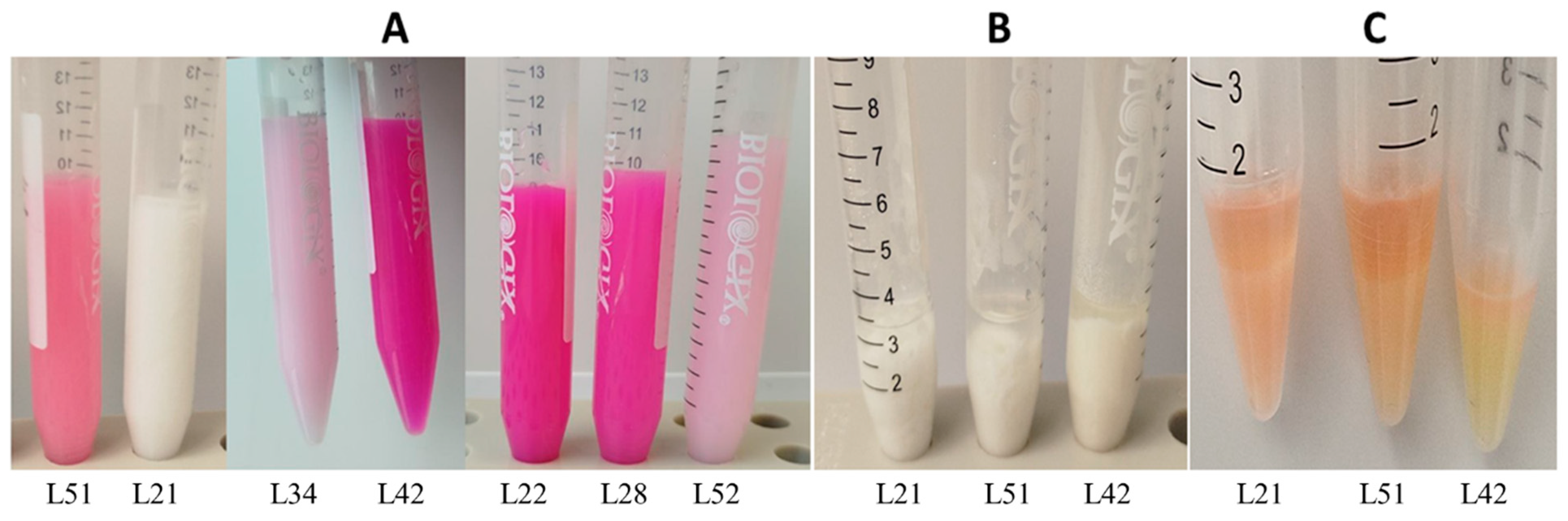

2.1. Microbiological Characterisation of Pure Cultures Isolated from the lakt1p Starter Culture

2.2. Analysis of the Metagenome of the Microbiological Consortium in Sample lakt1p

2.3. Bioinformatic Analysis of Sequenced Genomes

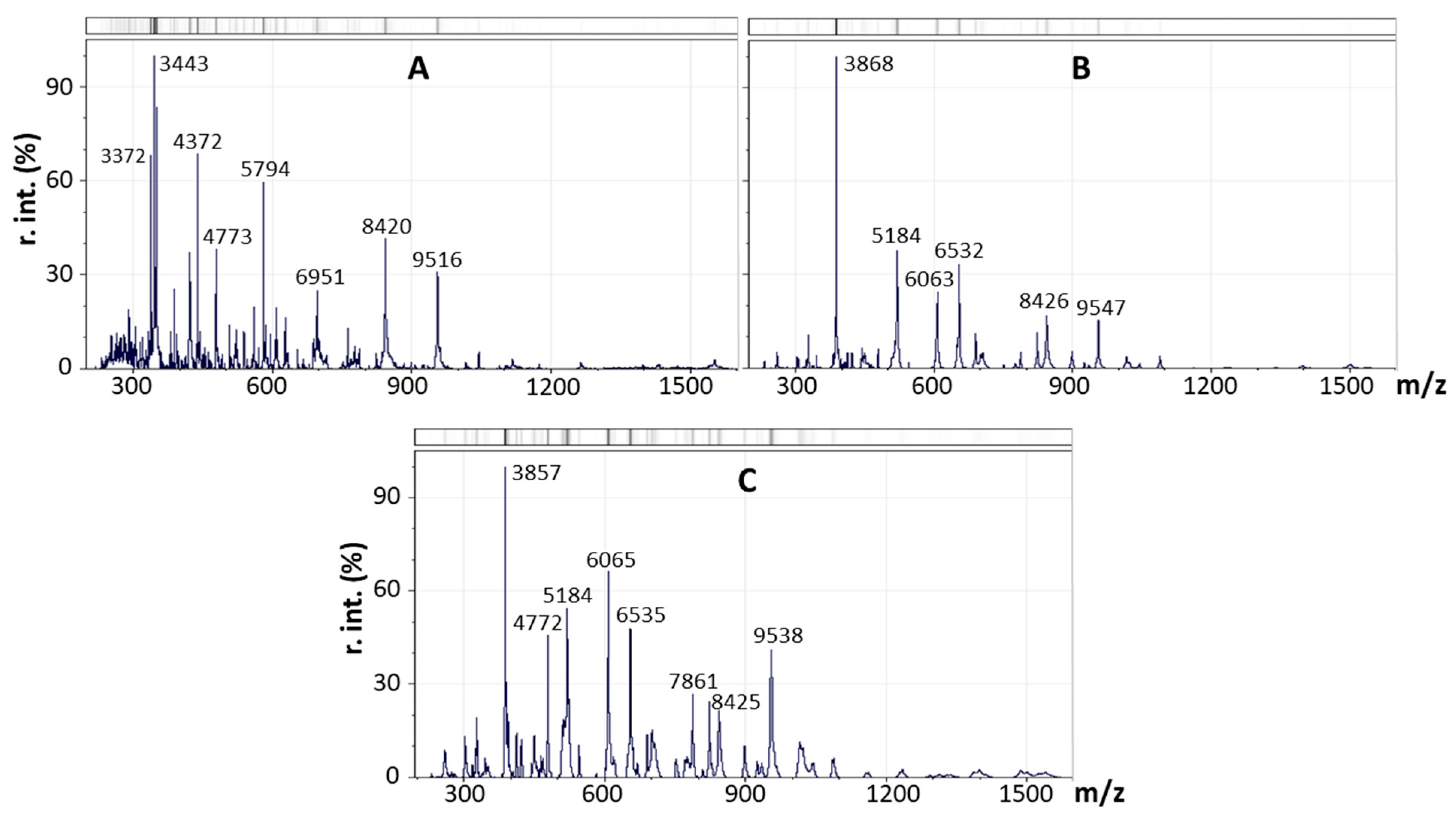

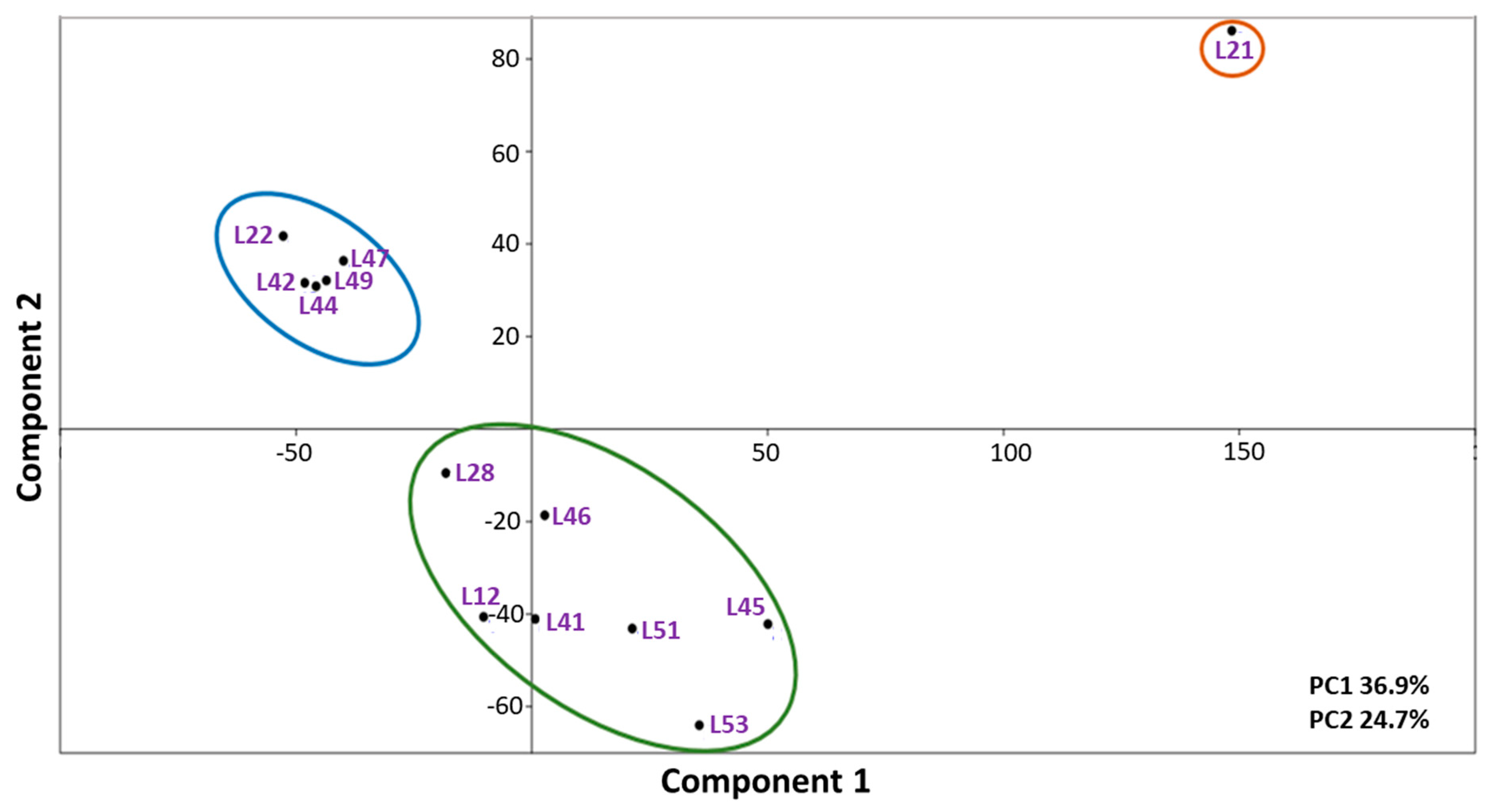

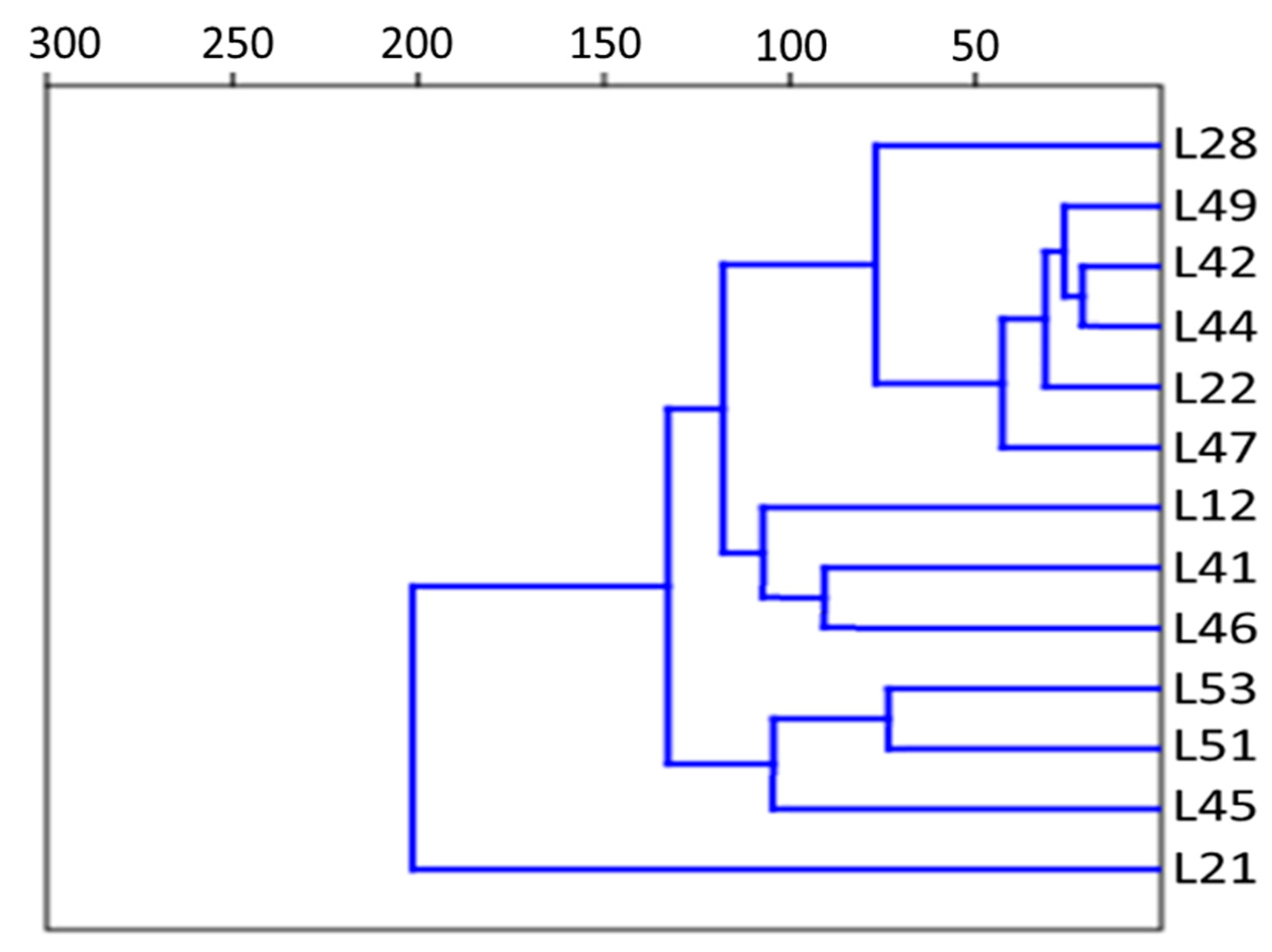

2.4. Mass Spectrometric Analysis of Strains After Separation of the lakt1p Consortium

2.5. Comparison of Exopolysaccharide Synthesis Genes in the Metagenome of the lakt1p Starter Culture and the Synthetic Metagenome

2.6. Analysis of the Peptidase Spectrum in the lakt1p Metagenome and in the Isolated Cultures

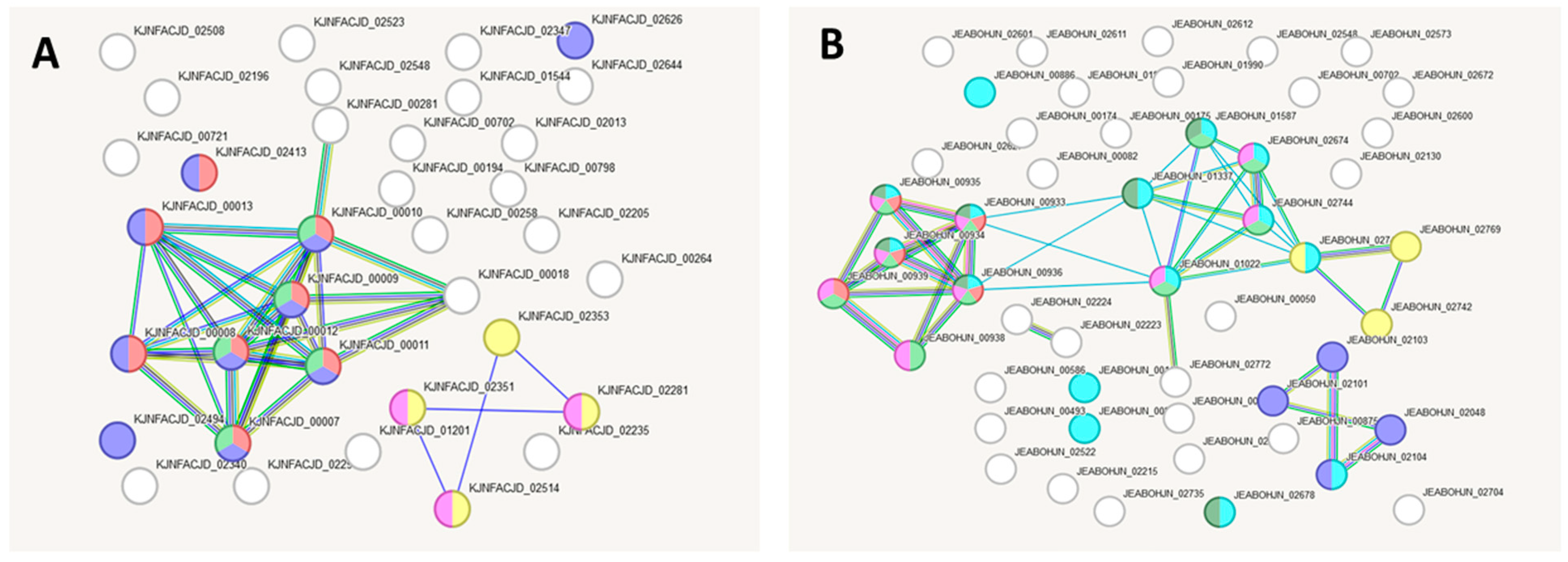

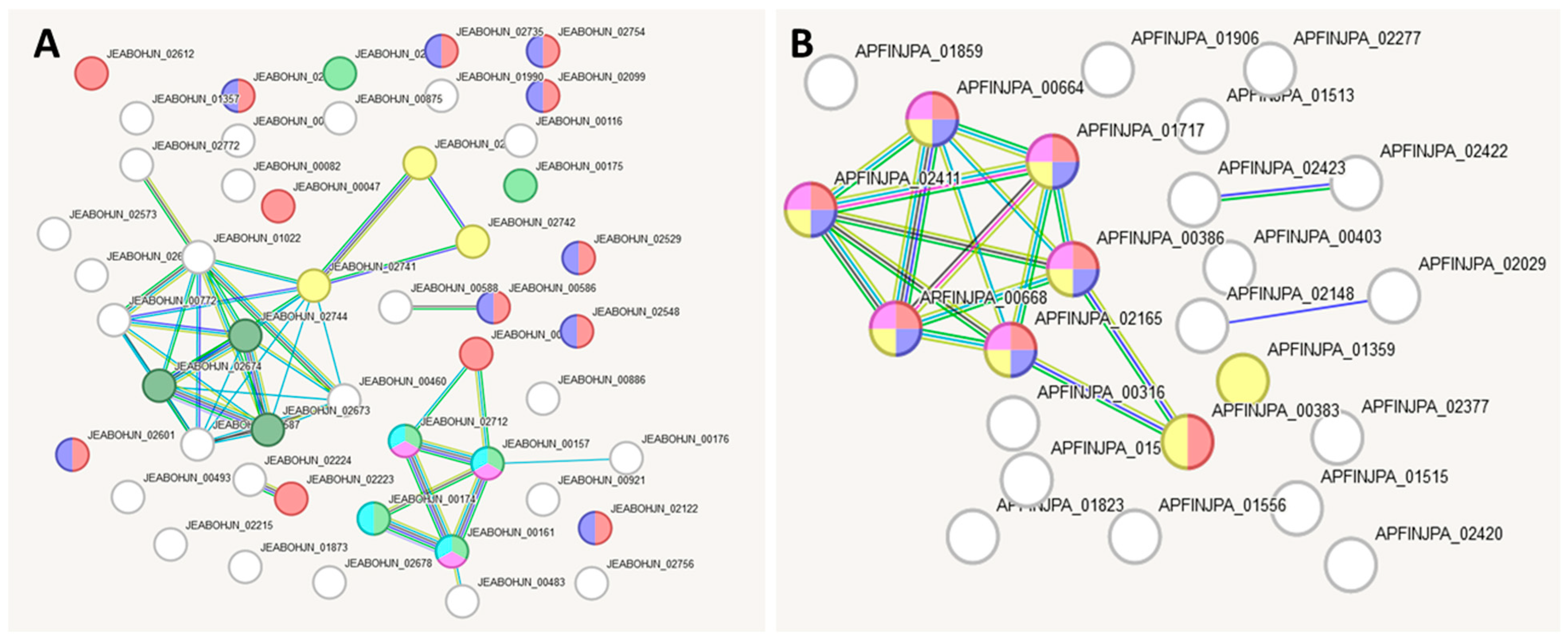

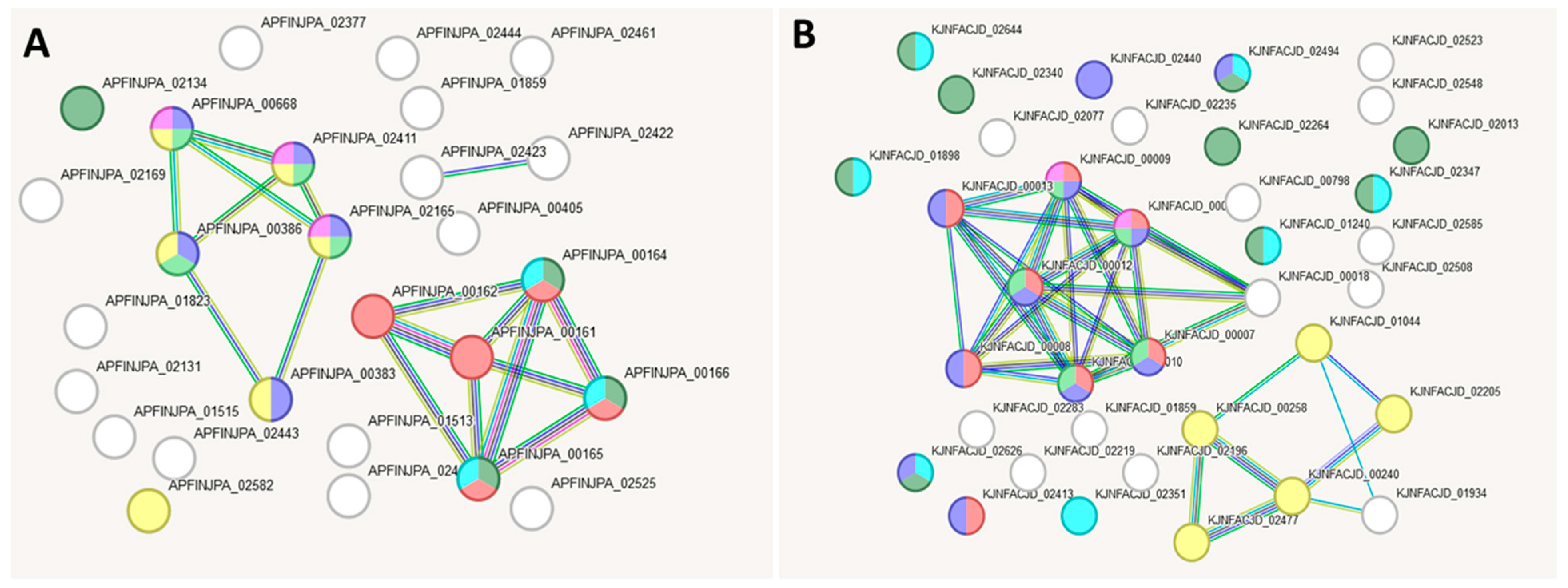

2.7. Bioinformatic Analysis of Gene Interaction Networks in Strains L21, L42 and L51 from the lakt1p Consortium

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Microbiological Methods

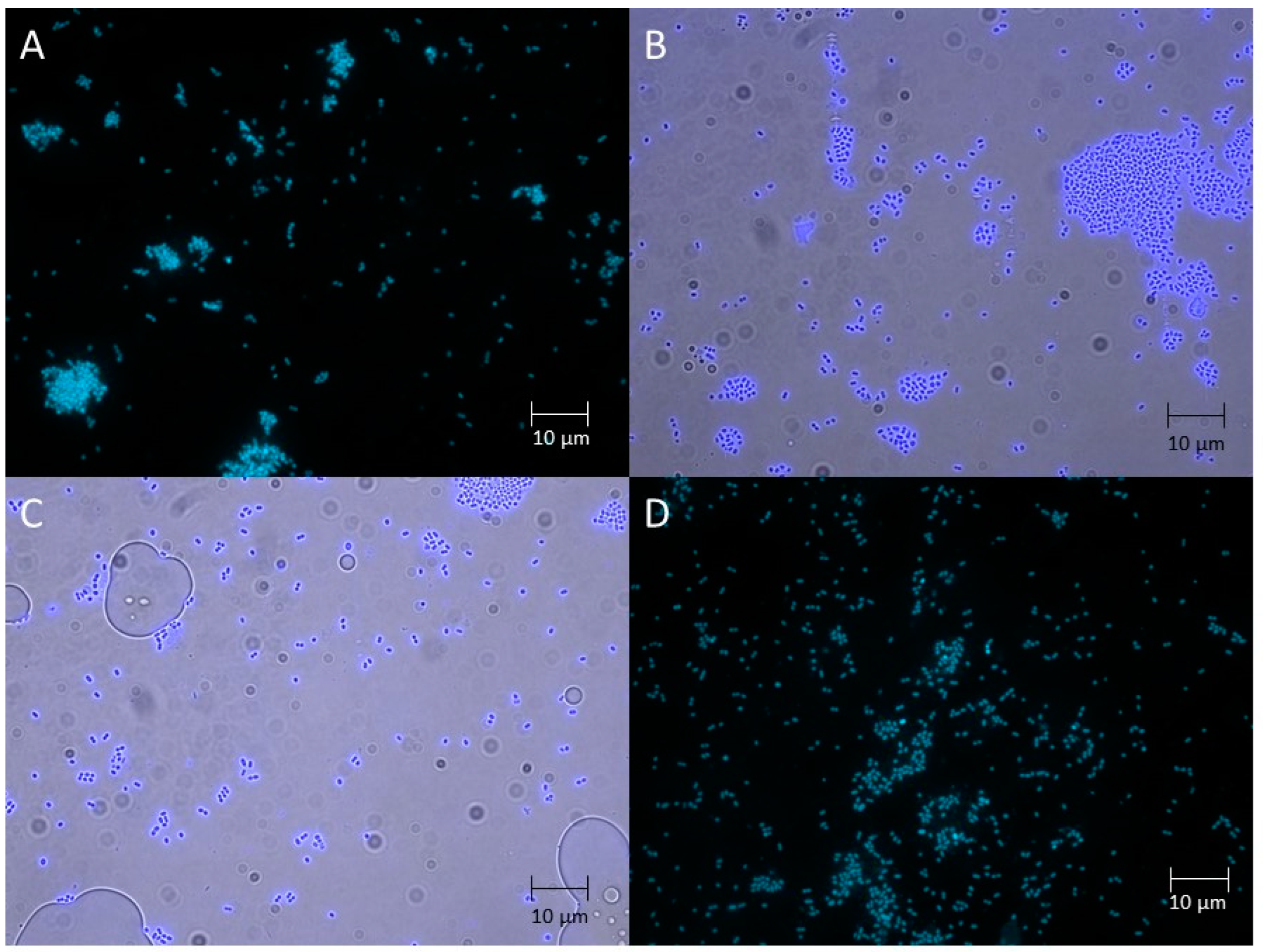

3.2. Sample Morphology Analysis by Fluorescence Microscopy

3.3. DNA Extraction, Library Preparation, Sequencing

3.4. Bioinformatic Analysis of Sequencing Data

3.5. Mass Spectrometric Analysis of Strain Proteomes

3.6. Preparation of Bacterial Cell Lysates for MALDI-TOF MS Measurement

3.7. Conditions for MALDI-TOF MS Measurement

3.8. Statistical Analysis of Mass Spectra

3.9. Bioinformatic Analysis: Gene Network Construction

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| N | L42 | L21 |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | ABC transporter ATP-binding protein YtrB | [Citrate [pro-3S]-lyase] ligase |

| 2. | Bacteriocin lactococcin B | 2-(5″-triphosphoribosyl)-3′-dephosphocoenzyme-A synthase |

| 3. | Cadmium resistance transcriptional regulatory protein CadC | 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate cytidylyltransferase |

| 4. | Cadmium-transporting ATPase | Apo-citrate lyase phosphoribosyl-dephospho-CoA transferase |

| 5. | Curved DNA-binding protein | Bis(5′-nucleosyl)-tetraphosphatase, symmetrical |

| 6. | General stress protein 18 | Citrate lyase acyl carrier protein |

| 7. | Glycosyltransferase GlyD | Citrate lyase alpha chain |

| 8. | Group II intron-encoded protein LtrA | Citrate lyase subunit beta |

| 9. | Homoserine O-succinyltransferase | Citrate/malate transporter |

| 10. | HTH-type transcriptional repressor YtrA | D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase DacA |

| 11. | IS21 family transposase IS712 | Galactose/methyl galactoside import ATP-binding protein MglA |

| 12. | IS3 family transposase IS1163 | GDP-L-fucose synthase |

| 13. | IS3 family transposase IS981 | GDP-mannose 4,6-dehydratase |

| 14. | IS3 family transposase IS-LL6 | Glucitol operon repressor |

| 15. | IS3 family transposase ISSag5 | HTH-type transcriptional regulator Hpr |

| 16. | IS3 family transposase ISWci2 | Intermembrane phospholipid transport system ATP-binding protein MlaF |

| 17. | IS4 family transposase IS1675 | IS256 family transposase IS1310 |

| 18. | K(+)/H(+) antiporter NhaP2 | IS256 family transposase IS905 |

| 19. | Multidrug resistance protein 3 | IS256 family transposase ISEfm2 |

| 20. | N-acetyl-alpha-D-glucosaminyl L-malate synthase | IS6 family transposase ISS1W |

| 21. | NADP-dependent 3-hydroxy acid dehydrogenase YdfG | IS6 family transposase ISTeha2 |

| 22. | Nitrogen fixation regulation protein FixK | IS982 family transposase ISLll1 |

| 23. | Oligopeptide-binding protein AppA | ISL3 family transposase ISSpn3 |

| 24. | Potassium-transporting ATPase KdpC subunit | L-threonine 3-dehydrogenase |

| 25. | Potassium-transporting ATPase potassium-binding subunit | NAD-dependent malic enzyme |

| 26. | putative ABC transporter ATP-binding protein YheS | Oxidoreductase YdhF |

| 27. | putative ATP-dependent Clp protease ATP-binding subunit | Peptide transporter CstA |

| 28. | putative HTH-type transcriptional regulator YdjF | PTS system oligo-beta-mannoside-specific EIIC component |

| 29. | putative MFS-type transporter YfcJ | putative acyl-CoA ligase YhfT |

| 30. | Putative mycofactocin radical SAM maturase MftC | putative SapB synthase |

| 31. | putative oxidoreductase YghA | Pyrrolidone-carboxylate peptidase |

| 32. | putative protein YqbD | Sorbitol operon regulator |

| 33. | Pyruvate/proton symporter BtsT | Spore coat protein SA |

| 34. | Replication initiation protein | Staphylopine export protein |

| 35. | Riboflavin biosynthesis protein | Transposase from transposon Tn916 |

| 36. | Sensor protein KdpD | Tyrosine recombinase XerD |

| 37. | Sensory transduction protein regX3 | UDP-galactopyranose mutase |

| 38. | Serine/threonine-protein kinase PknD | |

| 39. | SkfA peptide export ATP-binding protein SkfE | |

| 40. | Teichuronic acid biosynthesis protein TuaB | |

| 41. | Trans-aconitate 2-methyltransferase | |

| 42. | Transcriptional regulatory protein KdpE | |

| 43. | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 4-epimerase | |

| 44. | Xylose import ATP-binding protein XylG |

| N | L42 | L51 |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | ABC transporter ATP-binding protein YtrB | [LysW]-aminoadipate semialdehyde transaminase |

| 2. | ADP-L-glycero-D-manno-heptose-6-epimerase | 1-(5-phosphoribosyl)-5-[(5-phosphoribosylamino) methylideneamino] imidazole-4-carboxamide isomerase |

| 3. | Branched-chain amino acid transport system 2 carrier protein | 2,5-diketo-D-gluconic acid reductase A |

| 4. | Cadmium resistance transcriptional regulatory protein CadC | 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate cytidylyltransferase |

| 5. | Curved DNA-binding protein | Aconitate hydratase A |

| 6. | DNA topoisomerase 3 | Arsenical pump-driving ATPase |

| 7. | DNA-invertase hin | Arsenical resistance operon trans-acting repressor ArsD |

| 8. | dTDP-4-dehydrorhamnose 3,5-epimerase | Arsenical resistance protein Acr3 |

| 9. | General stress protein 18 | D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase DacA |

| 10. | Glycosyltransferase GlyD | Galactose/methyl galactoside import ATP-binding protein MglA |

| 11. | Homoserine O-succinyltransferase | Glucitol operon repressor |

| 12. | HTH-type transcriptional repressor YtrA | HTH-type transcriptional regulator Hpr |

| 13. | IS21 family transposase IS712 | Inner membrane protein YagU |

| 14. | IS3 family transposase IS1163 | IS6 family transposase ISTeha2 |

| 15. | IS3 family transposase ISLla3 | L-threonine 3-dehydrogenase |

| 16. | IS3 family transposase ISWci2 | Modification methylase FokI |

| 17. | IS4 family transposase IS1675 | Oxidoreductase YdhF |

| 18. | IS5 family transposase IS1194 | PTS system oligo-beta-mannoside-specific EIIC component |

| 19. | IS982 family transposase ISLla2 | putative acyl--CoA ligase YhfT |

| 20. | K(+)/H(+) antiporter NhaP2 | Putative O-antigen transporter |

| 21. | N-acetyl-alpha-D-glucosaminyl L-malate synthase | Staphylopine export protein |

| 22. | NADP-dependent 3-hydroxy acid dehydrogenase YdfG | Type-2 restriction enzyme BsuMI component YdiS |

| 23. | Oligoendopeptidase F, plasmid | UDP-galactopyranose mutase |

| 24. | Oligopeptide-binding protein AppA | UDP-glucose 4-epimerase |

| 25. | Phosphoribosyl isomerase A | UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase |

| 26. | putative ABC transporter ATP-binding protein YheS | [LysW]-aminoadipate semialdehyde transaminase |

| 27. | putative HTH-type transcriptional regulator YdjF | |

| 28. | putative MFS-type transporter YfcJ | |

| 29. | Putative mycofactocin radical SAM maturase MftC | |

| 30. | putative oxidoreductase YghA | |

| 31. | putative protein YjdJ | |

| 32. | putative protein YqbD | |

| 33. | Pyruvate/proton symporter BtsT | |

| 34. | Replication initiation protein | |

| 35. | Riboflavin biosynthesis protein | |

| 36. | Sensory transduction protein regX3 | |

| 37. | Serine/threonine-protein kinase PknD | |

| 38. | SkfA peptide export ATP-binding protein SkfE | |

| 39. | Teichuronic acid biosynthesis protein TuaB | |

| 40. | Type-1 restriction enzyme R protein | |

| 41. | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 4-epimerase | |

| 42. | Xylose import ATP-binding protein XylG | |

| 43. | ABC transporter ATP-binding protein YtrB | |

| 44. | ADP-L-glycero-D-manno-heptose-6-epimerase |

| N | L51 | L21 |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | [LysW]-aminoadipate semialdehyde transaminase | [Citrate [pro-3S]-lyase] ligase |

| 2. | 1-(5-phosphoribosyl)-5-[(5-phosphoribosylamino)methylideneamino] imidazole-4-carboxamide isomerase | 2-(5″-triphosphoribosyl)-3′-dephosphocoenzyme-A synthase |

| 3. | 2,5-diketo-D-gluconic acid reductase A | ADP-L-glycero-D-manno-heptose-6-epimerase |

| 4. | Aconitate hydratase A | Apo-citrate lyase phosphoribosyl-dephospho-CoA transferase |

| 5. | Arsenical pump-driving ATPase | Bis(5′-nucleosyl)-tetraphosphatase, symmetrical |

| 6. | Arsenical resistance operon trans-acting repressor ArsD | Branched-chain amino acid transport system 2 carrier protein |

| 7. | Arsenical resistance protein Acr3 | Citrate lyase acyl carrier protein |

| 8. | Bacteriocin lactococcin B | Citrate lyase alpha chain |

| 9. | Cadmium-transporting ATPase | Citrate lyase subunit beta |

| 10. | Group II intron-encoded protein LtrA | Citrate/malate transporter |

| 11. | Inner membrane protein YagU | DNA topoisomerase 3 |

| 12. | IS3 family transposase IS981 | DNA-invertase hin |

| 13. | IS3 family transposase IS-LL6 | dTDP-4-dehydrorhamnose 3,5-epimerase |

| 14. | IS3 family transposase ISSag5 | GDP-L-fucose synthase |

| 15. | Modification methylase FokI | GDP-mannose 4,6-dehydratase |

| 16. | Multidrug resistance protein 3 | Intermembrane phospholipid transport system ATP-binding protein MlaF |

| 17. | Nitrogen fixation regulation protein FixK | IS256 family transposase IS1310 |

| 18. | Potassium-transporting ATPase KdpC subunit | IS256 family transposase IS905 |

| 19. | Potassium-transporting ATPase potassium-binding subunit | IS256 family transposase ISEfm2 |

| 20. | putative ATP-dependent Clp protease ATP-binding subunit | IS3 family transposase ISLla3 |

| 21. | Putative O-antigen transporter | IS5 family transposase IS1194 |

| 22. | Sensor protein KdpD | IS6 family transposase ISS1W |

| 23. | Trans-aconitate 2-methyltransferase | IS982 family transposase ISLla2 |

| 24. | Transcriptional regulatory protein KdpE | IS982 family transposase ISLll1 |

| 25. | Type-2 restriction enzyme BsuMI component YdiS | ISL3 family transposase ISSpn3 |

| 26. | UDP-glucose 4-epimerase | NAD-dependent malic enzyme |

| 27. | UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase | Oligoendopeptidase F, plasmid |

| 28. | [LysW]-aminoadipate semialdehyde transaminase | Peptide transporter CstA |

| 29. | Phosphoribosyl isomerase A | |

| 30. | putative protein YjdJ | |

| 31. | putative SapB synthase | |

| 32. | Pyrrolidone-carboxylate peptidase | |

| 33. | Sorbitol operon regulator | |

| 34. | Spore coat protein SA | |

| 35. | Transposase from transposon Tn916 | |

| 36. | Type-1 restriction enzyme R protein | |

| 37. | Tyrosine recombinase XerD |

References

- Kochetkova, T.V.; Grabarnik, I.P.; Klyukina, A.A.; Zayulina, K.S.; Elizarov, I.M.; Shestakova, O.O.; Gavirova, L.A.; Malysheva, A.D.; Shcherbakova, P.A.; Barkhutova, D.D.; et al. Microbial Communities of Artisanal Fermented Milk Products from Russia. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elcheninov, A.G.; Zayulina, K.S.; Klyukina, A.A.; Kremneva, M.K.; Kublanov, I.V.; Kochetkova, T.V. Metagenomic Insights into the Taxonomic and Functional Features of Traditional Fermented Milk Products from Russia. Microorganisms 2023, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shangpliang, H.N.J.; Tamang, J.P. Metagenome-assembled genomes for biomarkers of bio-functionalities in Laal dahi, an Indian ethnic fermented milk product. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 402, 110300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuerman, M.; Wang, R.; Zhou, Y.; Tian, X.; Cui, Q.; Yi, H.; Gong, P.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, K.; Liu, T.; et al. Metagenomic insights into bacterial communities and functional genes associated with texture characteristics of Kazakh artisanal fermented milk Ayran in Xinjiang, China. Food Res. Int. 2023, 164, 112414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilal, Z.; Akhmetsadykova, S.; Baubekova, A.; Tormo, H.; Faye, B.; Konuspayeva, G. The Main Features and Microbiota Diversity of Fermented Camel Milk. Foods 2024, 13, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvina, L.A.; Gorskikh, V.G.; Anfilofyeva, I.Y. Milk Microbiology: A Teaching Aid. Novosibirsk State Agrarian University, Institute of Ecological and Food Biotechnology, 3rd ed.; Suppl. and Updated; Publishing House of NSAU: Novosibirsk, Russia, 2024; p. 105. [Google Scholar]

- Krasnikova, L.V.; Gunkova, P.I.; Markelova, V.V. Microbiology of Milk and Dairy Products: Laboratory Practical Training: Textbook; National Research University ITMO: St. Petersburg, Russia; Institute of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2013; p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- Khelissa, S.; Chihib, N.E.; Gharsallaoui, A. Conditions of nisin production by Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis and its main uses as a food preservative. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eicher, C.; Coulon, J.; Favier, M.; Alexandre, H.; Reguant, C.; Grandvalet, C. Citrate metabolism in lactic acid bacteria: Is there a beneficial effect for Oenococcus oeni in wine? Front. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1283220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Yoon, S.; Shin, H.; Jo, M.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.H. Isolation of Lactococcus lactis ssp. cremoris LRCC5306 and Optimization of Diacetyl Production Conditions for Manufacturing Sour Cream. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2021, 41, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullaeva, N.F. Modern concepts of the mechanism of action of lactic acid bacteria bacteriocins (review). Aktual. Probl. Gumanit. Yestestvennykh Nauk 2014, 10, 23–27. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Cui, Y.; Qu, X. Exopolysaccharides of lactic acid bacteria: Structure, bioactivity and associations: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 207, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Fattah, A.M.; Gamal-Eldeen, A.M.; Helmy, W.A.; Esawy, M.A. Antitumor and antioxidant activities of levan and its derivative from the isolate Bacillus subtilis NRC1aza. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 89, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajoka, M.S.R.; Mehwish, H.M.; Hayat, H.F.; Hussain, N.; Sarwar, S.; Aslam, H.; Nadeem, A.; Shi, J. Characterization, the Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity of Exopolysaccharide Isolated from Poultry Origin Lactobacilli. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2019, 11, 1132–1142, Correction in Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2019, 11, 1143–1144.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Ai, L.; Guo, B. Partial characterization and immunostimulatory activity of exopolysaccharides from Lactobacillus rhamnosus KF5. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 107, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahbal, S.; Hemme, D.; Desmazeaud, M. High cell wall-associated proteinase activity of some Streptococcus thermophilus strains (H-strains) correlated with a high acidification rate in milk. Le Lait 1991, 71, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galia, W.; Perrin, C.; Genay, M. Variability and molecular typing of Streptococcus thermophilus strains displaying different proteolytic and acidifying properties. Int. Dairy J. 2009, 19, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukotic, G.; Mirkovic, N.; Jovcic, B.; Miljkovic, M.; Strahinic, I.; Fira, D.; Radulovic, Z.; Kojic, M. Proteinase PrtP impairs lactococcin LcnB activity in Lactococcus lactis BGMN1-501: New insights into bacteriocin regulation. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 10, 6–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venema, K.; Abee, T.; Haandrikman, A.J.; Leenhouts, K.J.; Kok, J.; Konings, W.N.; Venema, G. Mode of Action of Lactococcin B, a Thiol-Activated Bacteriocin from Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 1041–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbour, C.A.; Nagar, R.; Bernstein, H.M.; Ghosh, S.; Al-Sammarraie, Y.; Dorfmueller, H.C.; Ferguson, M.A.J.; Stanley-Wall, N.R.; Imperiali, B. Defining early steps in Bacillus subtilis biofilm biosynthesis. MBio 2023, 14, e00948-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T. Paleontological Data Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; 400p, ISBN 978-1-119-93395-3. [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: Protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Proportion of Reads in the Metagenome, % | Reference Genome Used for Read Alignment |

|---|---|

| 85.9 | Lactococcus lactissubsp. diacetilactis |

| 25 | NZ CP061325.1 Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis bv. diacetilactis strain S50 plasmid pS6, complete sequence |

| 20 | NZ CP061326.1 Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis bv. diacetilactis strain S50 plasmid pS74, complete sequence |

| 15 | NZ CP061327.1 Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis bv. diacetilactis strain S50 plasmid pS7a, complete sequence |

| 8 | NZ CP061328.1 Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis bv. diacetilactis strain S50 plasmid pS7b, complete sequence |

| 6.7 | NZ CP061322.1 Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis bv. diacetilactis strain S50 chromosome, complete genome |

| 5.6 | NZ CP061323.1 Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis bv. diacetilactis strain S50 plasmid pS127, complete sequence |

| 5.6 | NZ CP061324.1 Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis bv. diacetilactis strain S50 plasmid pS19, complete sequence |

| 13 | Lactococcus lactissubsp. cremoris |

| 13 | NC 022369.1 Lactococcus cremoris subsp. cremoris KW2, complete sequence |

| 1.0061 | Lactococcus lactissubsp. lactis |

| 1 | NZ CP028160.1 Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis strain 14B4 chromosome, complete genome |

| 0.0061 | NZ CP028161.1 Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis strain 14B4 plasmid p14B4, complete sequence |

| Cluster Number | Strain Name |

|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | L1, L21, L34, L52 |

| Cluster 2 | L12, L41, L45, L46, L47, L49, L51, L53 |

| Cluster 3 | L22, L28, L29, L42, L44 |

| Strain Number | Cluster Number, Genomic Analysis | Cluster Number, Mass Spectrometry Analysis | Colour on Reddy’s Agar | Coagulation Time, Hours | Diacetyl Test Time, Min | Sample Acidity, °T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | 1 | – | yellow | 16 | 58 | 40 |

| L21 | 1 | 1 | yellow | 17 | 63 | 40 |

| L34 | 1 | – | yellow | 18 | 52 | 40 |

| L52 | 1 | – | yellow | 18 | 72 | 40 |

| L12 | 2 | 2 | white | 19 | 61 | 65 |

| L41 | 2 | 2 | white | 20 | 67 | 65 |

| L45 | 2 | 2 | white | 20 | 80 | 65 |

| L46 | 2 | 2 | white | 20 | 87 | 65 |

| L47 | 2 | 3 | white | 18 | 93 | 65 |

| L49 | 2 | 3 | white | 17 | 85 | 65 |

| L51 | 2 | 2 | white | 19 | 88 | 65 |

| L53 | 2 | 2 | white | 18 | 84 | 65 |

| L22 | 3 | 3 | purple | 17 | 76 | 80 |

| L28 | 3 | 2 | purple | 18 | 84 | 80 |

| L29 | 3 | – | purple | 19 | 73 | 75 |

| L42 | 3 | 3 | purple | 18 | 70 | 80 |

| L44 | 3 | 3 | purple | 20 | 64 | 75 |

| N | Genes Encoding Peptidases | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unique to the lakt1p Metagenome | Unique to the L. l. subsp. lactis Genome (GCF_003176835.1) | Common to the Reference Genome L. l. subsp. lactis (GCF_003176835.1) and the lakt1p Sample | |

| 1 | Aminopeptidase YpdF | Beta-Ala-Xaa dipeptidase | Aminopeptidase C |

| 2 | D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase DacA | D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase DacA precursor | Aminopeptidase N |

| 3 | Putative D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase | Gamma-D-glutamyl-L-lysine endopeptidase | D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase |

| 4 | Signal peptidase I U | Glutamyl aminopeptidase | Dipeptidase A |

| 5 | Pyrrolidone-carboxylate peptidase | Murein tetrapeptide carboxypeptidase | Lipoprotein signal peptidase |

| 6 | Peptidoglycan DL-endopeptidase CwlO precursor | Methionine aminopeptidase 1 | |

| 7 | putative murein peptide carboxypeptidase | Neutral endopeptidase | |

| 8 | putative peptidase | Oligoendopeptidase F, plasmid | |

| 9 | Peptidase T | ||

| 10 | Signal peptidase I T | ||

| 11 | Xaa-Pro dipeptidase | ||

| N | Genes Encoding Peptidases | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unique to the lakt1p Metagenome | Unique to the Synthetic Metagenome (from Reference Genomes of L. l. subsp. cremoris, L. l. subsp. diacetilactis, L. l. subsp. lactis) | Common to the Synthetic Metagenome and the lakt1p Sample | |

| 1 | Aminopeptidase YpdF | D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase DacA precursor | Aminopeptidase C |

| 2 | D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase DacA | D-gamma-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid endopeptidase CwlS precursor | Aminopeptidase N |

| 3 | Putative D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase | Gamma-D-glutamyl-L-lysine endopeptidase | Beta-Ala-Xaa dipeptidase |

| 4 | Pyrrolidone-carboxylate peptidase | Glutamyl endopeptidase precursor | D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase |

| 5 | Murein DD-endopeptidase MepM | Dipeptidase A | |

| 6 | Murein tetrapeptide carboxypeptidase | Glutamyl aminopeptidase | |

| 7 | Peptidoglycan DL-endopeptidase CwlO precursor | Lipoprotein signal peptidase | |

| 8 | putative endopeptidase precursor | Methionine aminopeptidase 1 | |

| 9 | putative murein peptide carboxypeptidase | Neutral endopeptidase | |

| 10 | putative peptidase | Oligoendopeptidase F, plasmid | |

| 11 | Peptidase T | ||

| 12 | Signal peptidase I T | ||

| 13 | Signal peptidase I U | ||

| 14 | Xaa-Pro dipeptidase | ||

| Cluster1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | EC Number | Gene Name | Process |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lcnB | lcnB | Bacteriocin lactococcin B | Antimicrobial peptide (bacteriocin) synthesis | ||

| epsL | epsL | epsL | 2.-.-.- | putative sugar transferase EpsL | Exopolysaccharide biosynthesis |

| pgmB | pgmB | pgmB | 5.4.2.6 | Beta-phosphoglucomutase | Biosynthesis of EPS precursors containing glucose and galactose |

| gtaB | gtaB | gtaB | 2.7.7.9 | UTP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase | |

| galK_1 | galK_1 | galK_1 | 2.7.1.6 | Galactokinase | |

| galK_2 | galK_2 | galK_2 | 2.7.1.6 | ||

| galT | galT | galT | 2.7.7.12 | Galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase | |

| mro | mro | mro | 5.1.3.3 | Aldose 1-epimerase (mutarotase) | |

| galE | 5.1.3.2 | UDP-glucose 4-epimerase | |||

| rfbA | rfbA | rfbA | 2.7.7.24 | Glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase 1 | Biosynthesis of EPS precursors containing rhamnose |

| rfbC_1 | rfbC | rfbC_1 | 5.1.3.- | Protein RmlC | |

| rfbC_2 | rfbC_2 | 5.1.3.13 | |||

| rfbB | 4.2.1.46 | dTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase | |||

| lacS | lacS | lacS | Lactose permease | Transport of lactose and galactose | |

| lacZ | lacZ | lacZ_1 | 3.2.1.23 | Beta-galactosidase | Hydrolysis of lactose into glucose and galactose |

| lacZ_2 | 3.2.1.23 | ||||

| mnaA | mnaA | mnaA | 5.1.3.14 | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase | Teichoic acid biosynthesis |

| ywqD | ywqD | ywqD | 2.7.10.2 | Tyrosine-protein kinase YwqD | Capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis |

| prsA_1 | prsA_1 | prsA_1 | 5.2.1.8 | Foldase protein PrsA | Protein secretion |

| prsA_2 | prsA_2 | prsA_2 | 5.2.1.8 | Foldase protein PrsA |

| Colour | Term ID | Term Description | Observed Gene Count | False Discovery Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| red | CL:3513 | Mixed, incl. Oxo-acid-lyase activity, and Symport | 8 | 1.44 × 10−8 |

| blue | CL:3474 | Mixed, incl. Glycerophospholipid metabolism, and Two-component system | 10 | 3.22 × 10−8 |

| lime-green | CL:3517 | Oxo-acid-lyase activity, and Acyl carrier activity | 5 | 7.48 × 10−6 |

| yellow | CL:4045 | Transposition, and DNA replication initiation | 4 | 0.0027 |

| magenta | CL:4057 | DNA replication initiation, and Transposition | 3 | 0.0082 |

| Colour | Term ID | Term Description | Observed Gene Count | False Discovery Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| darkgreen | GOCC:0098533 | ATPase dependent transmembrane transport complex | 7 | 0.00018 |

| red | CL:2853 | P-type potassium transmembrane transporter activity | 5 | 0.00019 |

| lime-green | CL:2693 | ABC transporters, and Peptide transport | 10 | 0.0016 |

| magenta | CL:2695 | ABC transporters, and Nickel cation transmembrane transporter activity | 9 | 0.0035 |

| blue | CL:3353 | Mixed, incl. Copper ion transport, and Ferric iron binding | 4 | 0.0035 |

| yellow | CL:3028 | Mixed, incl. Entry into host, and Collagen binding | 3 | 0.0183 |

| cyan | GO:0055085 | Transmembrane transport | 15 | 0.0443 |

| Colour | Term ID | Term Description | Observed Gene Count | False Discovery Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| blue | GO:0140097 | Catalytic activity, acting on DNA | 9 | 0.0352 |

| lime-green | CL:2293 | Mixed, incl. Polysaccharide biosynthetic process, and O-Antigen nucleotide sugar biosynthesis | 6 | 0.0173 |

| magenta | CL:2298 | Polyketide sugar unit biosynthesis | 3 | 0.035 |

| yellow | CL:3028 | Mixed, incl. Entry into host, and Collagen binding | 3 | 0.035 |

| darkgreen | CL:2759 | Nickel cation transmembrane transporter activity, and Periplasmic space | 3 | 0.035 |

| cyan | CL:2296 | Mixed, incl. Polyketide sugar unit biosynthesis, and Galactose metabolism | 4 | 0.035 |

| red | GO:0006259 | DNA metabolic process | 13 | 0.0426 |

| Colour | Term ID | Term Description | Observed Gene Count | False Discovery Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| magenta | map00520 | Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism | 6 | 0.0019 |

| red | CL:2607 | Mixed, incl. O-Antigen nucleotide sugar biosynthesis, and Capsule organisation | 7 | 1.45 × 10−6 |

| blue | CL:2608 | O-Antigen nucleotide sugar biosynthesis, and Galactose metabolic process | 6 | 4.62 × 10−6 |

| yellow | CL:2423 | Mixed, incl. Starch and sucrose metabolism, and Carbohydrate metabolic process | 8 | 0.0025 |

| Colour | Term ID | Term Description | Observed Gene Count | False Discovery Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cyan | GOCC:0031004 | Potassium ion-transporting ATPase complex | 3 | 0.0043 |

| dark green | GO:0019829 | ATPase-coupled cation transmembrane transporter activity | 4 | 0.0058 |

| red | CL:2267 | P-type potassium transmembrane transporter activity, and Phosphorelay signal transduction system | 5 | 9.57 × 10−6 |

| blue | CL:2607 | Mixed, incl. O-Antigen nucleotide sugar biosynthesis, and Capsule organisation | 5 | 0.0014 |

| lime-green | CL:2608 | O-Antigen nucleotide sugar biosynthesis, and Galactose metabolic process | 4 | 0.0059 |

| yellow | CL:2601 | Mixed, incl. Polysaccharide biosynthetic process, and Phosphotransferase activity, for other substituted phosphate groups | 6 | 0.0059 |

| magenta | CL:2610 | O-Antigen nucleotide sugar biosynthesis, and Galactose metabolism | 3 | 0.0226 |

| Colour | Term ID | Term Description | Observed Gene Count | False Discovery Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cyan | GOCC:0031004 | Potassium ion-transporting ATPase complex | 3 | |

| dark green | GO:0019829 | ATPase-coupled cation transmembrane transporter activity | 4 | 0.0058 |

| red | CL:2267 | P-type potassium transmembrane transporter activity, and Phosphorelay signal transduction system | 5 | 9.57 × 10−6 |

| blue | CL:2607 | Mixed, incl. O-Antigen nucleotide sugar biosynthesis, and Capsule organisation | 5 | 0.0014 |

| lime-green | CL:2608 | O-Antigen nucleotide sugar biosynthesis, and Galactose metabolic process | 4 | 0.0059 |

| yellow | CL:2601 | Mixed, incl. Polysaccharide biosynthetic process, and Phosphotransferase activity, for other substituted phosphate groups | 6 | 0.0059 |

| magenta | CL:2610 | O-Antigen nucleotide sugar biosynthesis, and Galactose metabolism | 3 | 0.0226 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Uvarova, Y.E.; Khlebodarova, T.M.; Vasilieva, A.R.; Shipova, A.A.; Babenko, V.N.; Zadorozhny, A.V.; Slynko, N.M.; Bogacheva, N.V.; Bukatich, E.Y.; Shlyakhtun, V.N.; et al. Genetic Characterisation of Closely Related Lactococcus lactis Strains Used in Dairy Starter Cultures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010292

Uvarova YE, Khlebodarova TM, Vasilieva AR, Shipova AA, Babenko VN, Zadorozhny AV, Slynko NM, Bogacheva NV, Bukatich EY, Shlyakhtun VN, et al. Genetic Characterisation of Closely Related Lactococcus lactis Strains Used in Dairy Starter Cultures. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):292. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010292

Chicago/Turabian StyleUvarova, Yuliya E., Tamara M. Khlebodarova, Asya R. Vasilieva, Aleksandra A. Shipova, Vladimir N. Babenko, Andrey V. Zadorozhny, Nikolay M. Slynko, Natalia V. Bogacheva, Ekaterina Y. Bukatich, Valeriya N. Shlyakhtun, and et al. 2026. "Genetic Characterisation of Closely Related Lactococcus lactis Strains Used in Dairy Starter Cultures" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010292

APA StyleUvarova, Y. E., Khlebodarova, T. M., Vasilieva, A. R., Shipova, A. A., Babenko, V. N., Zadorozhny, A. V., Slynko, N. M., Bogacheva, N. V., Bukatich, E. Y., Shlyakhtun, V. N., Korzhuk, A. V., Pavlova, E. Y., Chesnokov, D. O., & Peltek, S. E. (2026). Genetic Characterisation of Closely Related Lactococcus lactis Strains Used in Dairy Starter Cultures. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010292