Stabilization of the MAPK–Epigenetic Signaling Axis Underlies the Protective Effect of Thyme Oil Against Cadmium Stress in Root Meristem Cells of Vicia faba

Abstract

1. Introduction

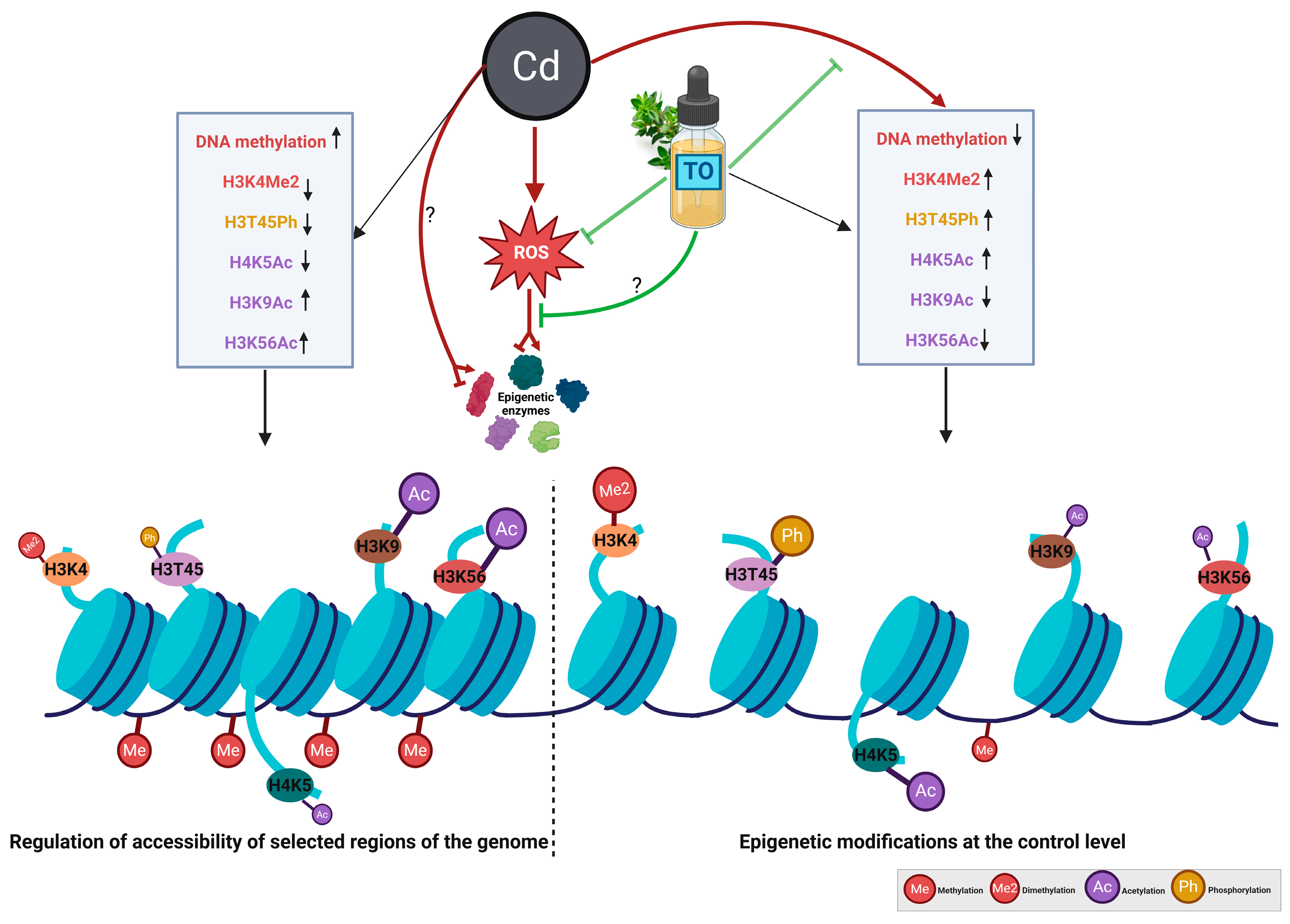

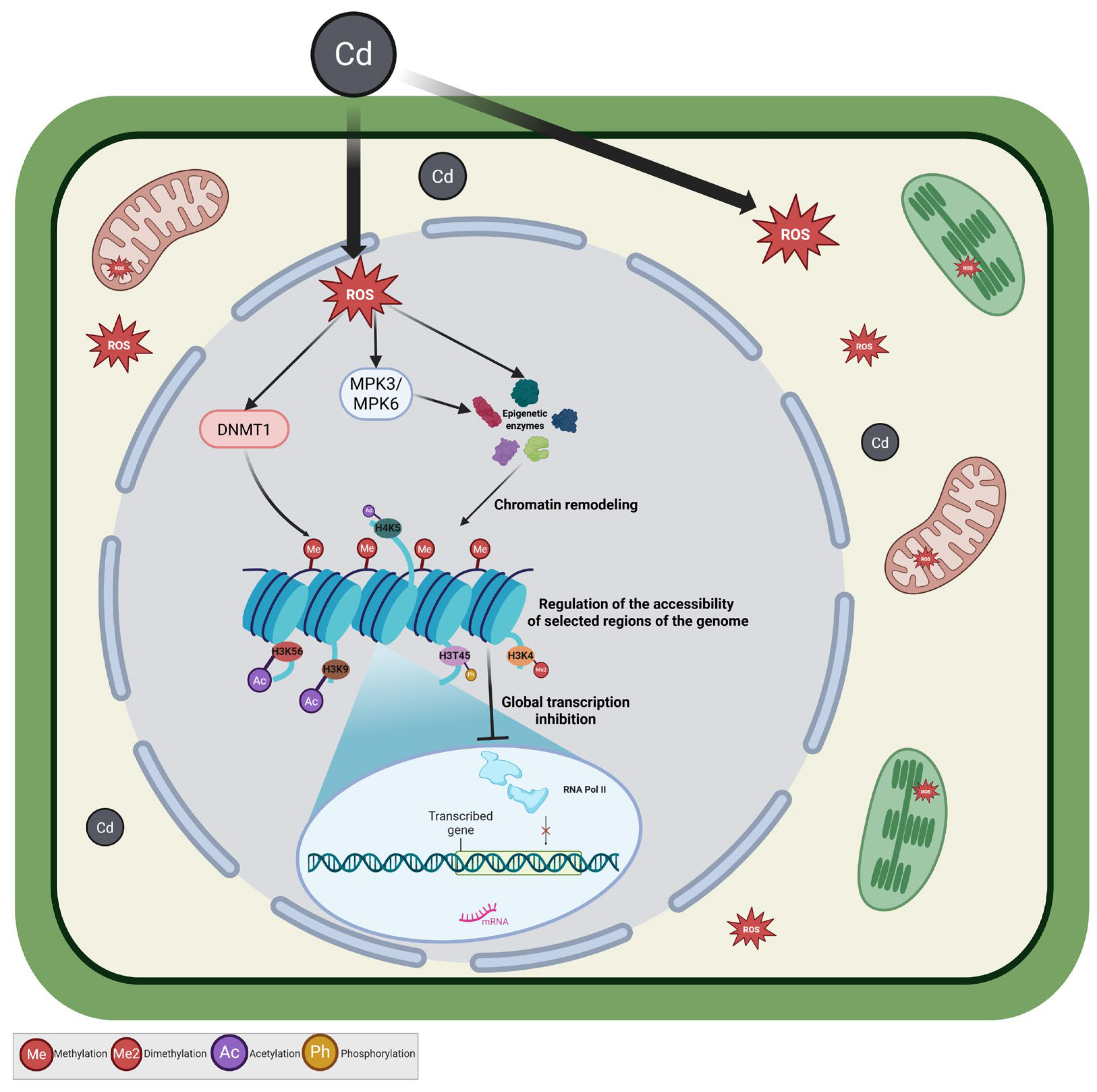

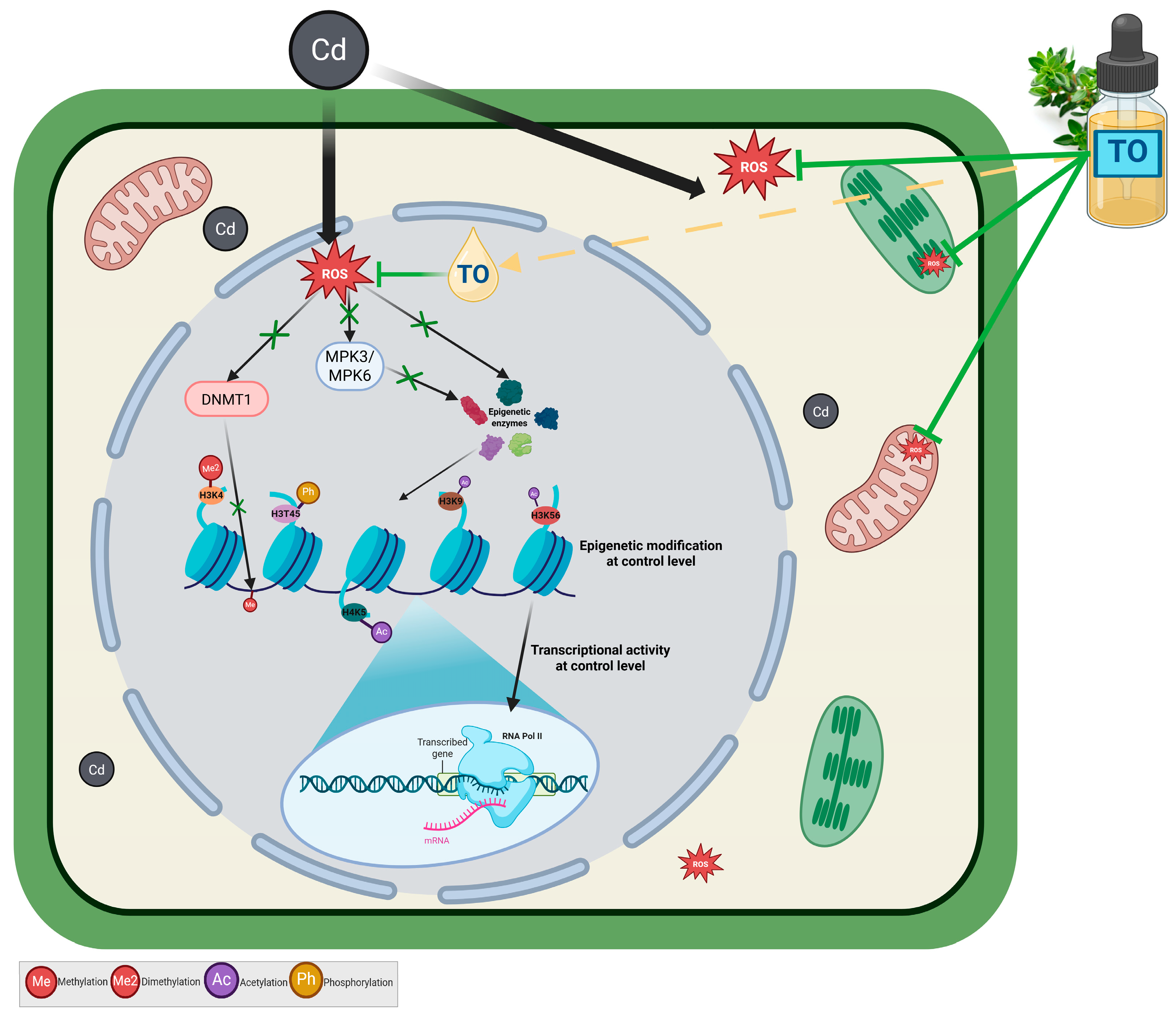

2. Results

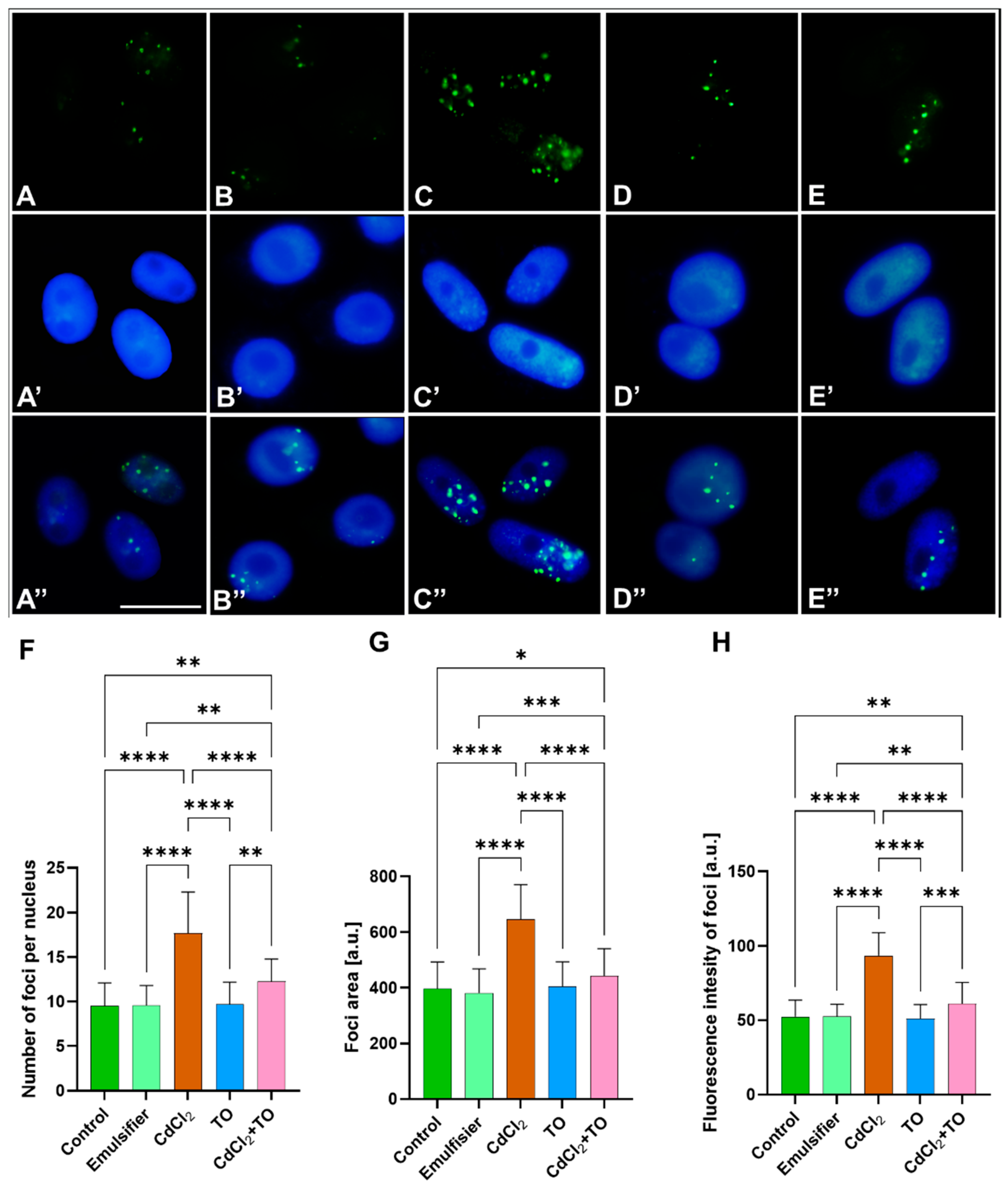

2.1. Immunodetection of Dually Phosphorylated MAPKs

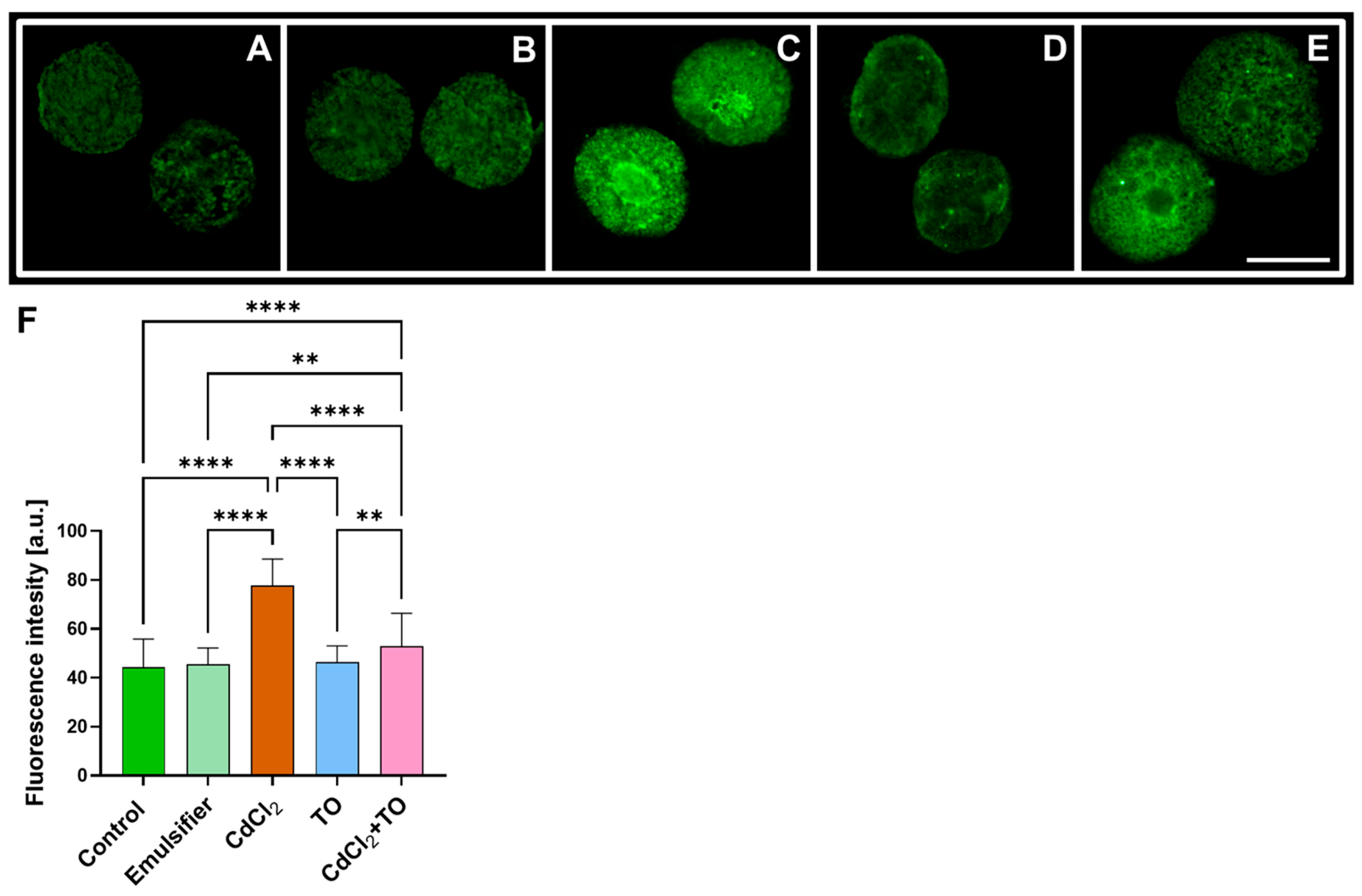

2.2. Immunodetection of 5-Methylcytosine (5-mC)

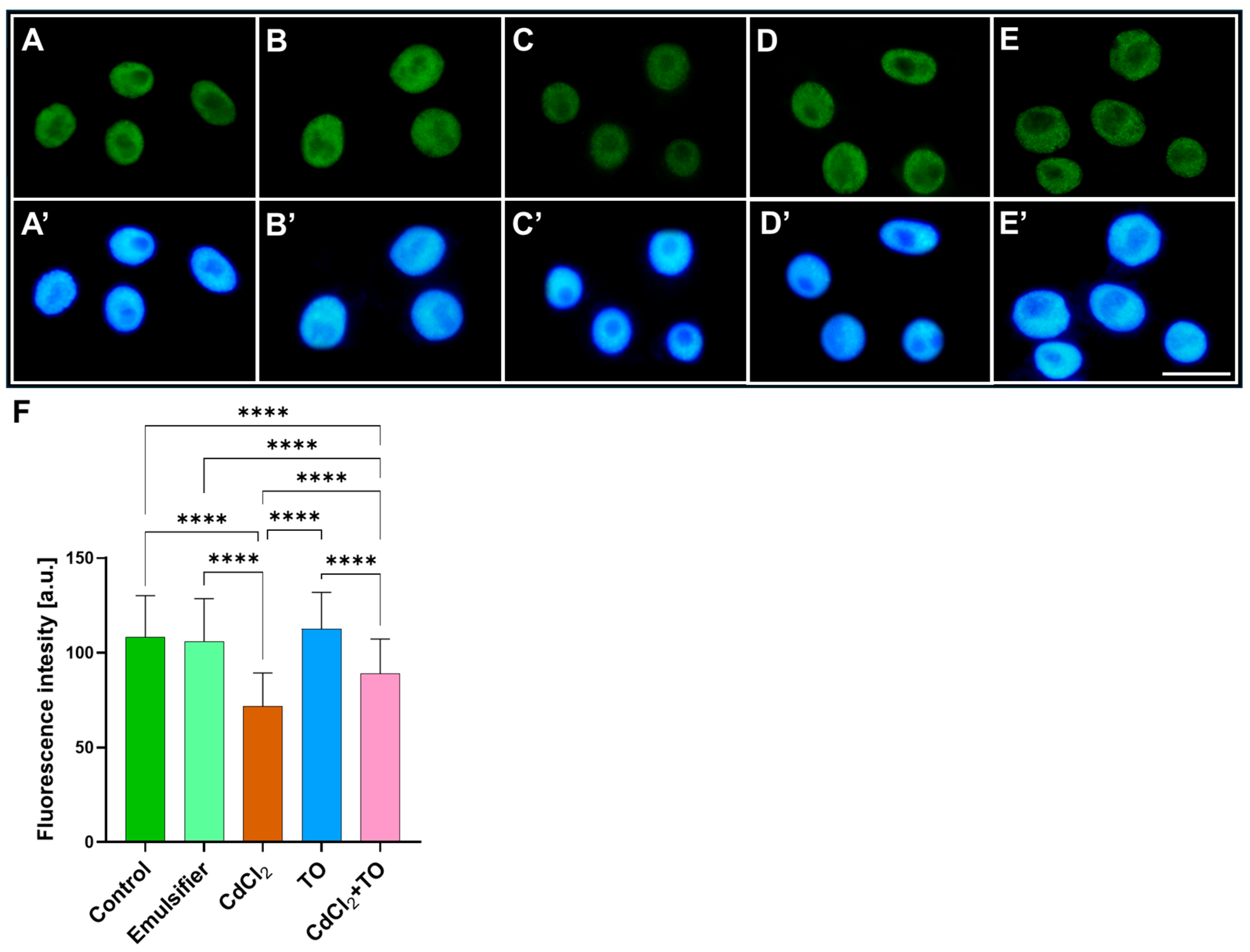

2.3. Dimethylation of Histone H3 on Lysine 4 (H3K4Me2)

2.4. Phosphorylation of Histone H3 on Threonine 45 (H3T45Ph)

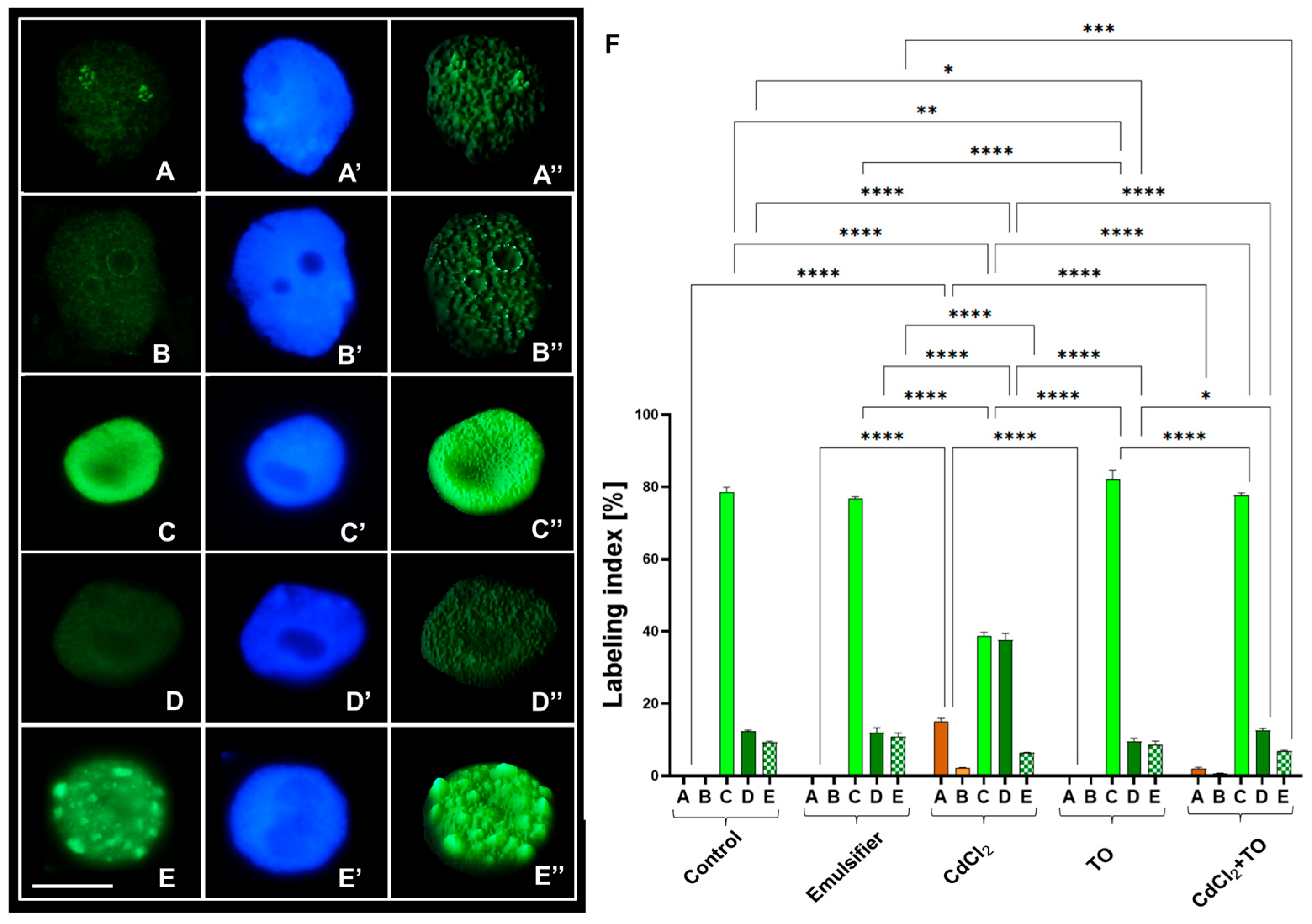

2.5. Acetylation of Histone H4 on Lysine 5 (H4K5Ac)

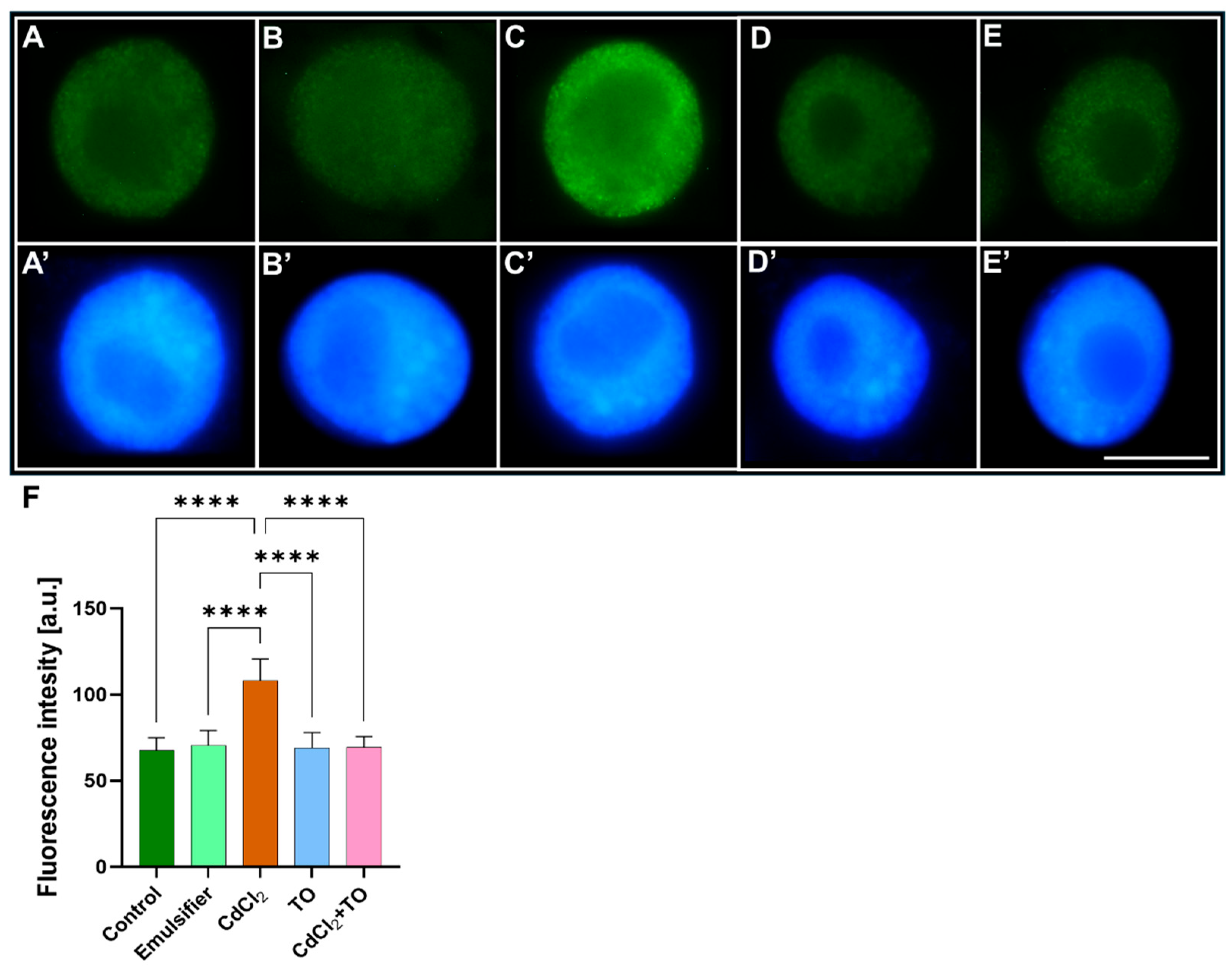

2.6. Acetylation of Histone H3 on Lysine 9 (H3K9Ac)

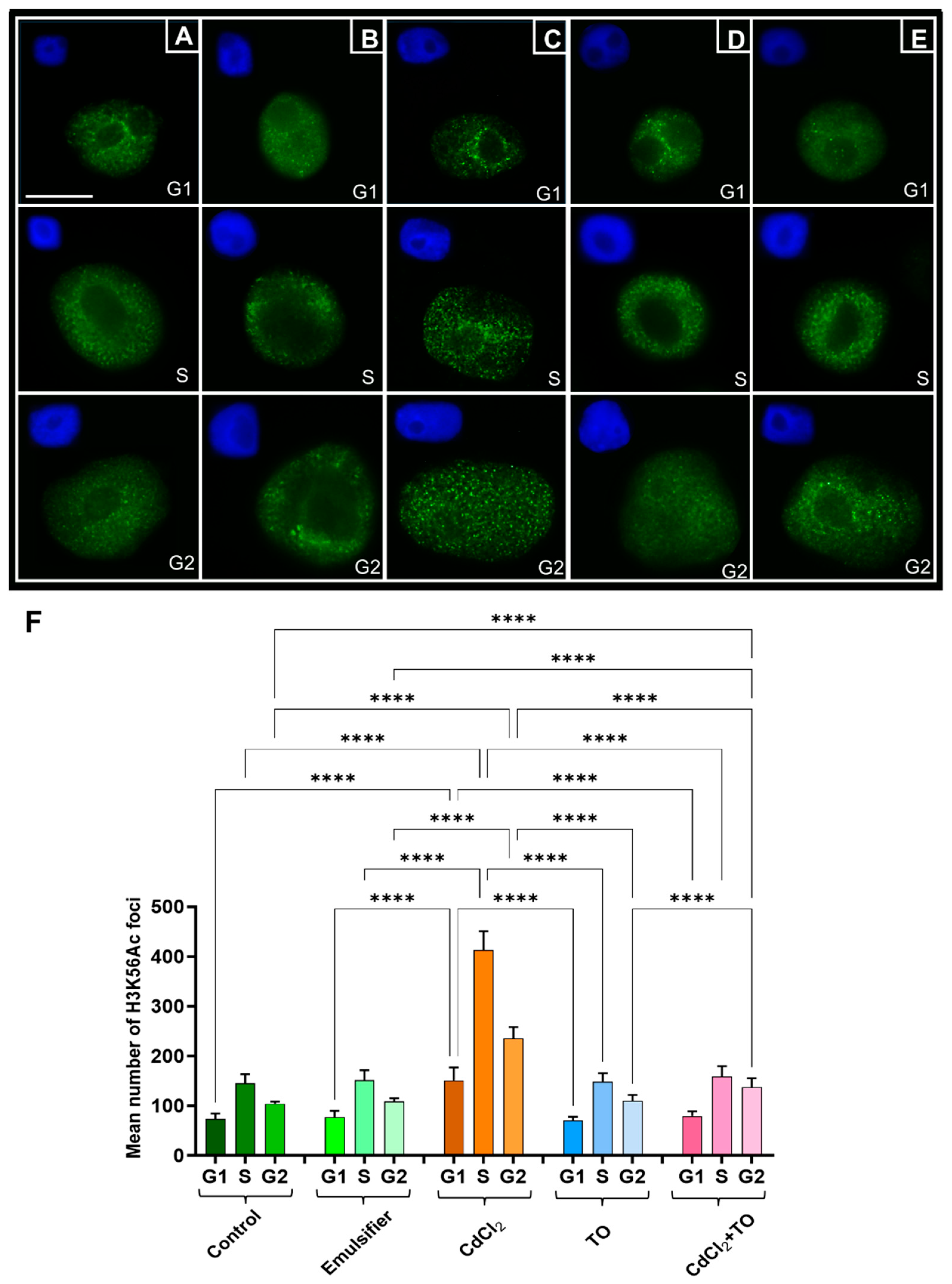

2.7. Acetylation of Histone H3 on Lysine 56 (H3K56Ac)

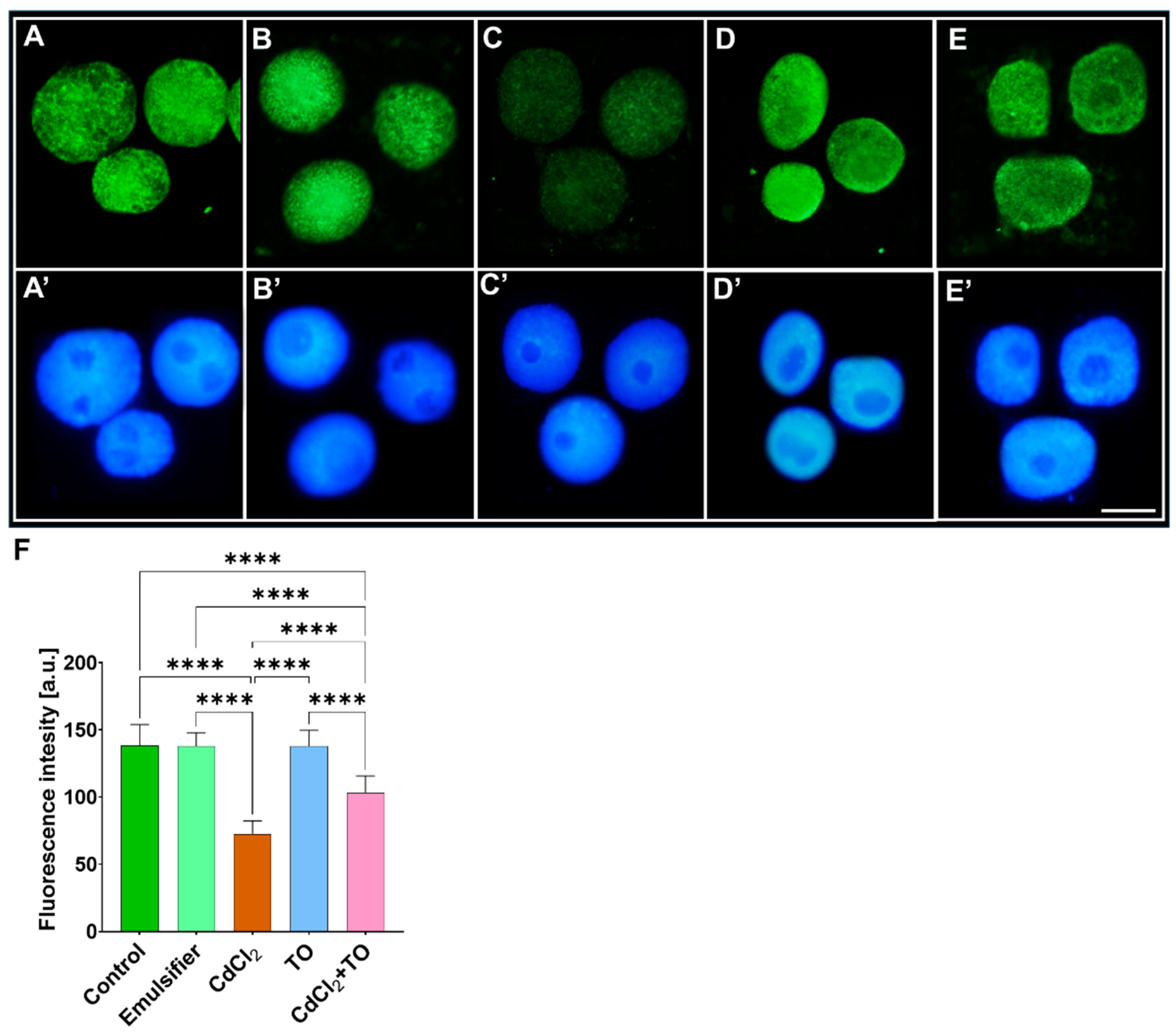

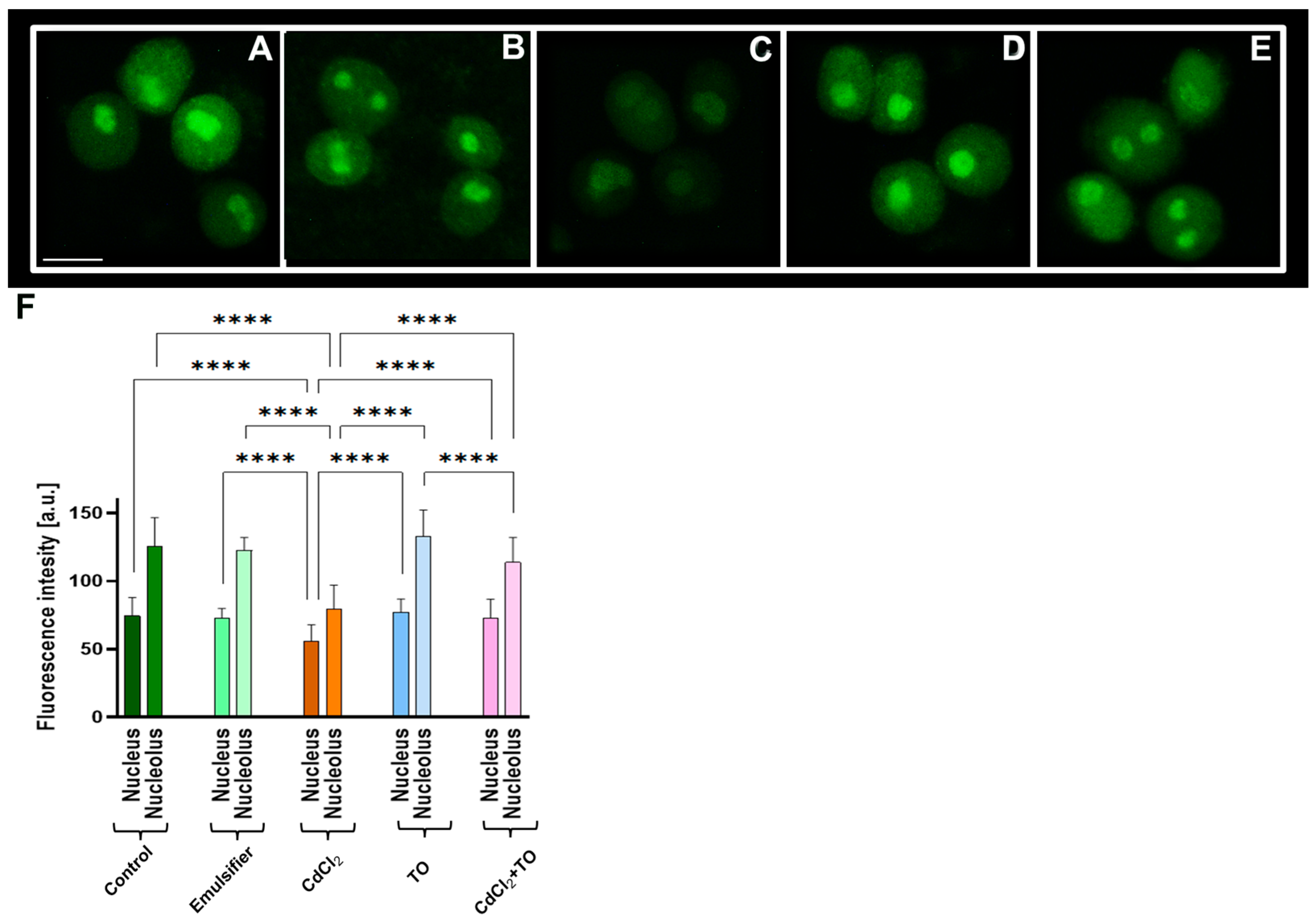

2.8. Changes in Transcription Dynamics

3. Discussion

3.1. Thyme Essential Oil Mitigates Cadmium-Induced Nuclear MAPK Activation

3.2. Thyme Essential Oil Attenuates Cadmium-Induced DNA Hypermethylation

3.3. Thyme Essential Oil Modulates Cadmium-Induced Histone Modifications

3.4. Thyme Essential Oil Preserves Transcription Under Cadmium Stress

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. Immunocytochemical Detection of Dually Phosphorylated MAPKs

4.3. Immunocytochemical Staining for DNA Methylation

4.4. Immunocytochemical Detection of Histone Methylation, Acetylation and Phosphorylation

4.5. 5-Ethynyl Uridine (EU) Labeling and Visualization of Nascent RNA

4.6. Microscopic Measurements, Observations, and Analyses

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Cd | Cadmium |

| TO | Thyme oil |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| 5-mC | 5-methylcytosine |

| MET1 | Methyltransferase 1 |

| DNMT1 | DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase 1 |

| CMT3 | Chromomethylase 3 |

| DRM2 | Domains rearranged methylase 2 |

| RdDM | RNA-directed DNA methylation |

| ROS1 | Repressor of silencing 1 |

| DME | Transcriptional activator Demeter |

| DML2 | Demeter-like protein 2 |

| DML3 | Demeter-like protein 3 |

| SUMO | Small ubiquitin-like modifier |

| HATs | Histone acetyltransferases |

| HDACs | Histone deacetylases |

| HMTs | Histone methyltransferases |

References

- Hussain, B.; Lin, Q.; Hamid, Y.; Sanaullah, M.; Di, L.; Hashmi, M.L.U.R.; Khan, M.B.; He, Z.; Yang, X. Foliage Application of Selenium and Silicon Nanoparticles Alleviates Cd and Pb Toxicity in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 712, 136497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, S.S. The Elements of Plant Micronutrients. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 512–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.N.; Tangpong, J.; Rahman, M.M. Toxicodynamics of Lead, Cadmium, Mercury and Arsenic- Induced Kidney Toxicity and Treatment Strategy: A Mini Review. Toxicol. Rep. 2018, 5, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Lin, F.F.; Wong, M.T.F.; Feng, X.L.; Wang, K. Identification of Soil Heavy Metal Sources from Anthropogenic Activities and Pollution Assessment of Fuyang County, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2009, 154, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, G.; Wu, X.; Zeng, F. Cadmium Accumulation in Plants: Insights from Phylogenetic Variation into the Evolution and Functions of Membrane Transporters. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, T.; Rizwan, M.; Ali, S.; Adrees, M.; Zia-ur-Rehman, M.; Qayyum, M.F.; Ok, Y.S.; Murtaza, G. Effect of Biochar on Alleviation of Cadmium Toxicity in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Grown on Cd-Contaminated Saline Soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 25668–25680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younis, U.; Malik, S.A.; Rizwan, M.; Qayyum, M.F.; Ok, Y.S.; Shah, M.H.R.; Rehman, R.A.; Ahmad, N. Biochar Enhances the Cadmium Tolerance in Spinach (Spinacia oleracea) through Modification of Cd Uptake and Physiological and Biochemical Attributes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 21385–21394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyno, E.; Klose, C.; Krieger-Liszkay, A. Origin of Cadmium-induced Reactive Oxygen Species Production: Mitochondrial Electron Transfer versus Plasma Membrane NADPH Oxidase. New Phytol. 2008, 179, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Tang, Y.; Gu, F.; Wang, X.; Yang, W.; Han, Y.; Ruan, Y. Phytochemical Analysis Reveals an Antioxidant Defense Response in Lonicera japonica to Cadmium-Induced Oxidative Stress. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuypers, A.; Vanbuel, I.; Iven, V.; Kunnen, K.; Vandionant, S.; Huybrechts, M.; Hendrix, S. Cadmium-Induced Oxidative Stress Responses and Acclimation in Plants Require Fine-Tuning of Redox Biology at Subcellular Level. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 199, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, H.; Huber, S.C. Regulation of Sucrose Metabolism in Higher Plants: Localization and Regulation of Activity of Key Enzymes. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2000, 35, 253–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, C.; Lescot, M.; Inzé, D.; De Veylder, L. Effect of Auxin, Cytokinin, and Sucrose on Cell Cycle Gene Expression in Arabidopsis thaliana cell Suspension Cultures. Plant Cell Tissue Organ. Cult. 2002, 69, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonak, C.; Nakagami, H.; Hirt, H. Heavy Metal Stress. Activation of Distinct Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Pathways by Copper and Cadmium. Plant Physiol. 2004, 136, 3276–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xu, B.; Liu, L.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, H.; Chen, W.; Shen, T.; Han, X.; Kontos, C.D.; Huang, S. Cadmium Induction of Reactive Oxygen Species Activates the mTOR Pathway, Leading to Neuronal Cell Death. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 50, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.K.; Pena, L.B.; Romero-Puertas, M.C.; Hernández, A.; Inouhe, M.; Sandalio, L.M. NADPH Oxidases Differentially Regulate ROS Metabolism and Nutrient Uptake under Cadmium Toxicity. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 509–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamsheer, K.M.; Jindal, S.; Laxmi, A. Evolution of TOR–SnRK Dynamics in Green Plants and Its Integration with Phytohormone Signaling Networks. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 2239–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Cruz, E.Y.; Arancibia-Hernández, Y.L.; Loyola-Mondragón, D.Y.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. Oxidative Stress and Its Role in Cd-Induced Epigenetic Modifications: Use of Antioxidants as a Possible Preventive Strategy. Oxygen 2022, 2, 177–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Han, X.; Lu, Z.; Qiu, W.; Yu, M.; Li, H.; He, Z.; Zhuo, R. MAPK Cascades and Transcriptional Factors: Regulation of Heavy Metal Tolerance in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, P.; Wu, J.; Li, T.-T.; Shi, P.; Ma, Q.; Di, D.-W. An Overview of the Mechanisms through Which Plants Regulate ROS Homeostasis under Cadmium Stress. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalapos, B.; Hlavová, M.; Nádai, T.V.; Galiba, G.; Bišová, K.; Dóczi, R. Early Evolution of the Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Family in the Plant Kingdom. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, K.; Vos, D.L.-D.; Leprince, A.-S.; Savouré, A.; Laurière, C. Analysis of the Arabidopsis Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Families: Organ Specificity and Transcriptional Regulation upon Water Stresses. Sch. Res. Exch. 2008, 143656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigeard, J.; Hirt, H. Nuclear Signaling of Plant MAPKs. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, A.L.; Rose, S.; Barratt, M.J.; Mahadevan, L.C. Phosphoacetylation of Histone H3 on c-Fos- and c-Jun-Associated Nucleosomes upon Gene Activation. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 3714–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Jiang, S.; Yu, X.; Cheng, C.; Chen, S.; Cheng, Y.; Yuan, J.S.; Jiang, D.; He, P.; Shan, L. Phosphorylation of Trihelix Transcriptional Repressor ASR3 by MAP KINASE4 Negatively Regulates Arabidopsis Immunity. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 839–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, M.E.; Rasmussen, M.W.; Palma, K.; Lolle, S.; Regué, À.M.; Bethke, G.; Glazebrook, J.; Zhang, W.; Sieburth, L.; Larsen, M.R.; et al. The mRNA Decay Factor PAT 1 Functions in a Pathway Including MAP Kinase 4 and Immune Receptor SUMM 2. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Eschen-Lippold, L.; Lassowskat, I.; Böttcher, C.; Scheel, D. Cellular Reprogramming through Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, A.H.; Eschen-Lippold, L.; Pecher, P.; Hoehenwarter, W.; Sinha, A.K.; Scheel, D.; Lee, J. Regulation of WRKY46 Transcription Factor Function by Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latrasse, D.; Jégu, T.; Li, H.; De Zelicourt, A.; Raynaud, C.; Legras, S.; Gust, A.; Samajova, O.; Veluchamy, A.; Rayapuram, N.; et al. MAPK-Triggered Chromatin Reprogramming by Histone Deacetylase in Plant Innate Immunity. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, A.; Chen, C.; Xie, T.; He, J.; He, Y. Methylation Analysis of CpG Islands in Pineapple SERK1 Promoter. Genes 2020, 11, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lister, R.; O’Malley, R.C.; Tonti-Filippini, J.; Gregory, B.D.; Berry, C.C.; Millar, A.H.; Ecker, J.R. Highly Integrated Single-Base Resolution Maps of the Epigenome in Arabidopsis. Cell 2008, 133, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichter, S.M.; Du, J.; Zhong, X. Structure and Mechanism of Plant DNA Methyltransferases. In DNA Methyltransferases—Role and Function; Jeltsch, A., Jurkowska, R.Z., Eds.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 1389, pp. 137–157. ISBN 978-3-031-11453-3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Lang, Z.; Zhu, J.-K. Dynamics and Function of DNA Methylation in Plants. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroud, H.; Do, T.; Du, J.; Zhong, X.; Feng, S.; Johnson, L.; Patel, D.J.; Jacobsen, S.E. Non-CG Methylation Patterns Shape the Epigenetic Landscape in Arabidopsis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014, 21, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Mohapatra, T. Dynamics of DNA Methylation and Its Functions in Plant Growth and Development. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 596236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Yang, Z.; Liu, L.; Duan, L. DNA Methylation in Plant Responses and Adaption to Abiotic Stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Zhu, C.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.; Duan, C. Epigenetic Regulation in Plant Abiotic Stress Responses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 62, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankovic-Valentin, N.; Melchior, F. Control of SUMO and Ubiquitin by ROS: Signaling and Disease Implications. Mol. Asp. Med. 2018, 63, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, M.; Seki, M. Histone Modifications Form Epigenetic Regulatory Networks to Regulate Abiotic Stress Response. Plant Physiol. 2020, 182, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berr, A.; Shafiq, S.; Shen, W.-H. Histone Modifications in Transcriptional Activation during Plant Development. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Gene Regul. Mech. 2011, 1809, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberharter, A.; Becker, P.B. Histone Acetylation: A Switch between Repressive and Permissive Chromatin: Second in Review Series on Chromatin Dynamics. EMBO Rep. 2002, 3, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Lin, Y.-C.J.; Wang, P.; Zhang, B.; Li, M.; Chen, S.; Shi, R.; Tunlaya-Anukit, S.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; et al. The AREB1 Transcription Factor Influences Histone Acetylation to Regulate Drought Responses and Tolerance in Populus trichocarpa. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 663–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Kikuchi, A.; Kamada, H. The Arabidopsis Histone Deacetylases HDA6 and HDA19 Contribute to the Repression of Embryonic Properties after Germination. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetto, D.; Avvakumov, N.; Côté, J. Histone Phosphorylation: A Chromatin Modification Involved in Diverse Nuclear Events. Epigenetics 2012, 7, 1098–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, P.; Allis, C.D.; Sassone-Corsi, P. Signaling to Chromatin through Histone Modifications. Cell 2000, 103, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Du, J. Structure and Mechanism of Histone Methylation Dynamics in Arabidopsis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2022, 67, 102211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Lu, F.; Cui, X.; Cao, X. Histone Methylation in Higher Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 395–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, A.J.; Kouzarides, T. Regulation of Chromatin by Histone Modifications. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenuwein, T.; Allis, C.D. Translating the Histone Code. Science 2001, 293, 1074–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermans, C.; Chen, J.; Coppens, F.; Inzé, D.; Verbruggen, N. Low Magnesium Status in Plants Enhances Tolerance to Cadmium Exposure. New Phytol. 2011, 192, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soković, M.D.; Vukojević, J.; Marin, P.D.; Brkić, D.D.; Vajs, V.; Van Griensven, L.J.L.D. Chemical Composition of Essential Oils of Thymus and Mentha Species and Their Antifungal Activities. Molecules 2009, 14, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, J.M.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A.; Gavahian, M.; Marszałek, K.; Eş, I.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Barba, F.J. Understanding the Potential Benefits of Thyme and Its Derived Products for Food Industry and Consumer Health: From Extraction of Value-Added Compounds to the Evaluation of Bioaccessibility, Bioavailability, Anti-Inflammatory, and Antimicrobial Activities. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 2879–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiniaková, S.; Ácsová, A.; Hojerová, J.; Krepsová, Z.; Kreps, F. Ceylon Cinnamon and Clove Essential Oils as Promising Free Radical Scavengers for Skin Care Products. Acta Chim. Slovaca 2022, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpaz, S.; Glatman, L.; Drabkin, V.; Gelman, A. Effects of Herbal Essential Oils Used To Extend the Shelf Life of Freshwater-Reared Asian Sea Bass Fish (Lates calcarifer). J. Food Prot. 2003, 66, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, F.; Nabi, S.; Idliki, R.B.; Alimirzaei, M.; Barkhordar, S.M.A.; Shafaei, N.; Zareian, M.; Karimi, E.; Oskoueian, E. Thyme Oil Nanoemulsion Enhanced Cellular Antioxidant and Suppressed Inflammation in Mice Challenged by Cadmium-Induced Oxidative Stress. Waste Biomass Valor. 2022, 13, 3139–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gocek-Szczurtek, N.; Żabka, A.; Wróblewski, M.; Kukula-Koch, W.; Szczeblewski, P.; Polit, J.T. Thyme Oil Mitigates Cadmium-Induced Oxidative and Genotoxic Stress in Vicia faba Root Meristem Cells under in vitro Conditions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 38689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandur, E.; Micalizzi, G.; Mondello, L.; Horváth, A.; Sipos, K.; Horváth, G. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.) Essential Oils Prepared at Different Plant Phenophases on Pseudomonas aeruginosa LPS-Activated THP-1 Macrophages. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalczyk, A.; Przychodna, M.; Sopata, S.; Bodalska, A.; Fecka, I. Thymol and Thyme Essential Oil—New Insights into Selected Therapeutic Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.N.; Rehman, N.U.; Karim, A.; Imam, F.; Hamad, A.M. Protective Effect of Thymus serrulatus Essential Oil on Cadmium-Induced Nephrotoxicity in Rats, through Suppression of Oxidative Stress and Downregulation of NF-κB, iNOS, and Smad2 mRNA Expression. Molecules 2021, 26, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.A.; Ali, A.A.A.A.; Abdullah, S.A.G. Protective Role of Thyme Oil (Thymus vulgaris) Against Cadmium Chloride-Induced Renal Damage in Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio). J. Basrah Res. (Sci.) 2024, 50, 298–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maresca, V.; Badalamenti, N.; Ilardi, V.; Bruno, M.; Bontempo, P.; Basile, A. Chemical Composition of Thymus leucotrichus var. creticus Essential Oil and Its Protective Effects on Both Damage and Oxidative Stress in Leptodictyum riparium Hedw. Induced by Cadmium. Plants 2022, 11, 3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winnicki, K.; Żabka, A.; Bernasińska, J.; Matczak, K.; Maszewski, J. Immunolocalization of Dually Phosphorylated MAPKs in Dividing Root Meristem Cells of Vicia faba, Pisum sativum, Lupinus luteus and Lycopersicon esculentum. Plant Cell Rep. 2015, 34, 905–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.K.; Jaggi, M.; Raghuram, B.; Tuteja, N. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Signaling in Plants under Abiotic Stress. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011, 6, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hann, C.T.; Ramage, S.F.; Negi, H.; Bequette, C.J.; Vasquez, P.A.; Stratmann, J.W. Dephosphorylation of the MAP Kinases MPK6 and MPK3 Fine-Tunes Responses to Wounding and Herbivory in Arabidopsis. Plant Sci. 2024, 339, 111962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taj, G.; Agarwal, P.; Grant, M.; Kumar, A. MAPK Machinery in Plants: Recognition and Response to Different Stresses through Multiple Signal Transduction Pathways. Plant Signal. Behav. 2010, 5, 1370–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saijo, Y.; Loo, E.P. Plant Immunity in Signal Integration between Biotic and Abiotic Stress Responses. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, T.K.; Heinz, M.N.; Lundberg, D.J.; Brooks, A.M.; Lew, T.T.S.; Silmore, K.S.; Koman, V.B.; Ang, M.C.-Y.; Khong, D.T.; Singh, G.P.; et al. A Theory of Mechanical Stress-Induced H2O2 Signaling Waveforms in Planta. J. Math. Biol. 2023, 86, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, V.; Hille, J.; Mueller-Roeber, B.; Gechev, T.S. ROS-Mediated Abiotic Stress-Induced Programmed Cell Death in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, S.A.; Tanveer, M.; Hussain, S.; Bao, M.; Wang, L.; Khan, I.; Ullah, E.; Tung, S.A.; Samad, R.A.; Shahzad, B. Cadmium Toxicity in Maize (Zea mays L.): Consequences on Antioxidative Systems, Reactive Oxygen Species and Cadmium Accumulation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 17022–17030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.-M.; Kim, K.E.; Kim, K.-C.; Nguyen, X.C.; Han, H.J.; Jung, M.S.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, S.H.; Park, H.C.; Yun, D.-J.; et al. Cadmium Activates Arabidopsis MPK3 and MPK6 via Accumulation of Reactive Oxygen Species. Phytochemistry 2010, 71, 614–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S. Heavy Metal Stress–Induced Activation of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Signalling Cascade in Plants. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 41, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yan, S.; Zhao, L.; Tan, J.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, F.; Wang, P.; Hou, H.; Li, L. Histone Acetylation Associated Up-Regulation of the Cell Wall Related Genes Is Involved in Salt Stress Induced Maize Root Swelling. BMC Plant Biol. 2014, 14, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnusamy, V.; Zhu, J.-K. Epigenetic Regulation of Stress Responses in Plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2009, 12, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, C.-M.; Hsiao, L.-J.; Huang, H.-J. Cadmium Activates a Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Gene and MBP Kinases in Rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004, 45, 1306–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genchi, G.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Lauria, G.; Carocci, A.; Catalano, A. The Effects of Cadmium Toxicity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesildag, K.; Gur, C.; Ileriturk, M.; Kandemir, F.M. Evaluation of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, Apoptosis, Oxidative DNA Damage and Metalloproteinases in the Lungs of Rats Treated with Cadmium and Carvacrol. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 1201–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholijani, N.; Gharagozloo, M.; Farjadian, S.; Amirghofran, Z. Modulatory Effects of Thymol and Carvacrol on Inflammatory Transcription Factors in Lipopolysaccharide-Treated Macrophages. J. Immunotoxicol. 2016, 13, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, S.; Khan, A.R. Plant Epigenetics and Crop Improvement. In PlantOmics: The Omics of Plant Science; Barh, D., Khan, M.S., Davies, E., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2015; pp. 157–179. ISBN 978-81-322-2171-5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Kimatu, J.N.; Xu, K.; Liu, B. DNA Cytosine Methylation in Plant Development. J. Genet. Genom. 2010, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miryeganeh, M. Plants’ Epigenetic Mechanisms and Abiotic Stress. Genes 2021, 12, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriraman, A.; Debnath, T.K.; Xhemalce, B.; Miller, K.M. Making It or Breaking It: DNA Methylation and Genome Integrity. Essays Biochem. 2020, 64, 687–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, J.-S.; Lee, J.; Lee, K.K.; Park, O.-S.; Choi, H.-S.; Seo, P.J.; Cho, H.-T.; Frost, J.M.; Fischer, R.L.; et al. The DME Demethylase Regulates Sporophyte Gene Expression, Cell Proliferation, Differentiation, and Meristem Resurrection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2026806118, Correction in Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2311112120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2311112120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.-D.; Sun, J.-W.; Huang, L.-Y.; Chen, N.; Wang, Q.-W. Effects of Cadmium Stress on DNA Methylation in Soybean. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2021, 35, 1696–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y.; Dong, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, K.; Ying, J.; Li, C.; Liu, L. Melatonin-Induced DNA Demethylation of Metal Transporters and Antioxidant Genes Alleviates Lead Stress in Radish Plants. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, E.; Atmaca, H.; Kisim, A.; Uzunoglu, S.; Uslu, R.; Karaca, B. Effects of Thymus serpyllum Extract on Cell Proliferation, Apoptosis and Epigenetic Events in Human Breast Cancer Cells. Nutr. Cancer 2012, 64, 1245–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirot, L.; Jullien, P.E.; Ingouff, M. Evolution of CG Methylation Maintenance Machinery in Plants. Epigenomes 2021, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnegan, E.J.; Kovac, K.A. Plant DNA methyltransferases. Plant Mol. Biol. 2000, 43, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakaidos, P.; Karagiannis, D.; Rampias, T. Resolving DNA Damage: Epigenetic Regulation of DNA Repair. Molecules 2020, 25, 2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Han, J. The Role of Histone Modification in DNA Replication-Coupled Nucleosome Assembly and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasani, E.; Giannelli, G.; Varotto, S.; Visioli, G.; Bellin, D.; Furini, A.; DalCorso, G. Epigenetic Control of Plant Response to Heavy Metals. Plants 2023, 12, 3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żabka, A.; Gocek, N.; Winnicki, K.; Szczeblewski, P.; Laskowski, T.; Polit, J.T. Changes in Epigenetic Patterns Related to DNA Replication in Vicia faba Root Meristem Cells under Cadmium-Induced Stress Conditions. Cells 2021, 10, 3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-M.; To, T.K.; Ishida, J.; Morosawa, T.; Kawashima, M.; Matsui, A.; Toyoda, T.; Kimura, H.; Shinozaki, K.; Seki, M. Alterations of Lysine Modifications on the Histone H3 N-Tail under Drought Stress Conditions in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008, 49, 1580–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, H.; Zhao, L.; Zheng, X.; Gautam, M.; Yue, M.; Hou, J.; Chen, Z.; Wang, P.; Li, L. Dynamic Changes in Histone Modification Are Associated with Upregulation of Hsf and rRNA Genes during Heat Stress in Maize Seedlings. Protoplasma 2019, 256, 1245–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabin, J.; Fortuny, A.; Polo, S.E. Epigenome Maintenance in Response to DNA Damage. Mol. Cell 2016, 62, 712–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-T.; Wu, K. Role of Histone Deacetylases HDA6 and HDA19 in ABA and Abiotic Stress Response. Plant Signal. Behav. 2010, 5, 1318–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; He, S.; Huang, M.; Tan, J.; Zhao, L.; Yan, S.; Li, H.; Zhou, K.; Liang, Y.; et al. Cold Stress Selectively Unsilences Tandem Repeats in Heterochromatin Associated with Accumulation of H3K9ac. Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 2130–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-M.; To, T.K.; Ishida, J.; Matsui, A.; Kimura, H.; Seki, M. Transition of Chromatin Status During the Process of Recovery from Drought Stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012, 53, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadouriya, S.L.; Mehrotra, S.; Basantani, M.K.; Loake, G.J.; Mehrotra, R. Role of Chromatin Architecture in Plant Stress Responses: An Update. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 603380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Wang, J.; Xu, F. Methylation Hallmarks on the Histone Tail as a Linker of Osmotic Stress and Gene Transcription. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 967607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokholok, D.K.; Harbison, C.T.; Levine, S.; Cole, M.; Hannett, N.M.; Lee, T.I.; Bell, G.W.; Walker, K.; Rolfe, P.A.; Herbolsheimer, E.; et al. Genome-Wide Map of Nucleosome Acetylation and Methylation in Yeast. Cell 2005, 122, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barski, A.; Cuddapah, S.; Cui, K.; Roh, T.-Y.; Schones, D.E.; Wang, Z.; Wei, G.; Chepelev, I.; Zhao, K. High-Resolution Profiling of Histone Methylations in the Human Genome. Cell 2007, 129, 823–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oya, S.; Takahashi, M.; Takashima, K.; Kakutani, T.; Inagaki, S. Transcription-Coupled and Epigenome-Encoded Mechanisms Direct H3K4 Methylation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bernatavichute, Y.V.; Cokus, S.; Pellegrini, M.; Jacobsen, S.E. Genome-Wide Analysis of Mono-, Di- and Trimethylation of Histone H3 Lysine 4 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Biol. 2009, 10, R62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, F.S.; Fischl, H.; Murray, S.C.; Mellor, J. Is H3K4me3 Instructive for Transcription Activation? BioEssays 2017, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Xu, Z.; Clauder-Münster, S.; Steinmetz, L.M.; Buratowski, S. Set3 HDAC Mediates Effects of Overlapping Noncoding Transcription on Gene Induction Kinetics. Cell 2012, 150, 1158–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, H.; Sugimoto, K.; Tarr, P.T.; Temman, H.; Kadokura, S.; Inui, Y.; Sakamoto, T.; Sasaki, T.; Aida, M.; Suzuki, T.; et al. Primed Histone Demethylation Regulates Shoot Regenerative Competency. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, K.; Yin, L.; Yu, Y.; Qi, J.; Shen, W.-H.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, A. H3K4me2 Functions as a Repressive Epigenetic Mark in Plants. Epigenetics Chromatin 2019, 12, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meissner, A.; Mikkelsen, T.S.; Gu, H.; Wernig, M.; Hanna, J.; Sivachenko, A.; Zhang, X.; Bernstein, B.E.; Nusbaum, C.; Jaffe, D.B.; et al. Genome-Scale DNA Methylation Maps of Pluripotent and Differentiated Cells. Nature 2008, 454, 766–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Lu, C. The Interplay between DNA and Histone Methylation: Molecular Mechanisms and Disease Implications. EMBO Rep. 2021, 22, e51803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Guo, L.; Yuan, Y.; Hu, S.; Guo, F.; Zhao, H.; Yun, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Ni, D.; et al. Ectopic Overexpression of Histone H3K4 Methyltransferase CsSDG36 from Tea Plant Decreases Hyperosmotic Stress Tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamal, K.Y.; Khodaeiaminjan, M.; Yahya, G.; El-Tantawy, A.A.; El-Moneim, D.A.; El-Esawi, M.A.; Abd-Elaziz, M.A.A.; Nassrallah, A.A. Modulation of Cell Cycle Progression and Chromatin Dynamic as Tolerance Mechanisms to Salinity and Drought Stress in Maize. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 172, 684–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehove, M.; Wang, T.; North, J.; Luo, Y.; Dreher, S.J.; Shimko, J.C.; Ottesen, J.J.; Luger, K.; Poirier, M.G. Histone Core Phosphorylation Regulates DNA Accessibility. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 22612–22621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armeev, G.A.; Kniazeva, A.S.; Komarova, G.A.; Kirpichnikov, M.P.; Shaytan, A.K. Histone Dynamics Mediate DNA Unwrapping and Sliding in Nucleosomes. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.P.; Phillips, J.; Anderson, S.; Qiu, Q.; Shabanowitz, J.; Smith, M.M.; Yates, J.R.; Hunt, D.F.; Grant, P.A. Histone H3 Thr 45 Phosphorylation Is a Replication-Associated Post-Translational Modification in S. cerevisiae. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurd, P.J.; Bannister, A.J.; Halls, K.; Dawson, M.A.; Vermeulen, M.; Olsen, J.V.; Ismail, H.; Somers, J.; Mann, M.; Owen-Hughes, T.; et al. Phosphorylation of Histone H3 Thr-45 Is Linked to Apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 16575–16583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-H.; Kang, B.-H.; Jang, H.; Kim, T.W.; Choi, J.; Kwak, S.; Han, J.; Cho, E.-J.; Youn, H.-D. AKT Phosphorylates H3-Threonine 45 to Facilitate Termination of Gene Transcription in Response to DNA Damage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 4505–4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, F.; Tang, D.; Li, Z.; Kashif, M.H.; Khan, A.; Lu, H.; Jia, R.; Chen, P. Molecular Cloning and Subcellular Localization of Six HDACs and Their Roles in Response to Salt and Drought Stress in Kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.). Biol. Res. 2019, 52, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.; Rehrauer, H.; Mansuy, I.M. Genome-Wide Analysis of H4K5 Acetylation Associated with Fear Memory in Mice. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewinska, A.; Wnuk, M.; Grzelak, A.; Bartosz, G. Nucleolus as an Oxidative Stress Sensor in the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Redox Rep. 2010, 15, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapio, R.T.; Burns, C.J.; Pestov, D.G. Effects of Hydrogen Peroxide Stress on the Nucleolar Redox Environment and Pre-rRNA Maturation. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 678488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, M.; Gautam, M.; Chen, Z.; Hou, J.; Zheng, X.; Hou, H.; Li, L. Histone Acetylation of 45S rDNA Correlates with Disrupted Nucleolar Organization during Heat Stress Response in Zea mays L. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 172, 2079–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Hu, Y.; Wang, L.; Xiao, X.; Yin, F.; Cao, X.; Sui, M.; Yao, Y. Epigenetic Modifications of 45S rDNA Associates with the Disruption of Nucleolar Organisation during Cd Stress Response in Pakchoi. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 270, 115859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Henry, H.; Tian, L. Drought-inducible Changes in the Histone Modification H3K9ac Are Associated with Drought-responsive Gene Expression in Brachypodium Distachyon. Plant Biol. J. 2020, 22, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo-Franco, J.J.; Sosa, C.C.; Ghneim-Herrera, T.; Quimbaya, M. Epigenetic Control of Plant Response to Heavy Metal Stress: A New View on Aluminum Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 602625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhao, L.; Hou, H.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Gao, F.; Yan, S.; Li, L. Epigenetic Changes Are Associated with Programmed Cell Death Induced by Heat Stress in Seedling Leaves of Zea mays. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Ding, Y.; Sun, X.; Xie, S.; Wang, D.; Liu, X.; Su, L.; Wei, W.; Pan, L.; Zhou, D.-X. Histone Deacetylase HDA9 Negatively Regulates Salt and Drought Stress Responsiveness in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 1703–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Liu, J.; Guo, M.; Ouyang, W.; Yan, J.; Xiong, L.; Li, X. Drought-Responsive Dynamics of H3K9ac-Marked 3D Chromatin Interactions Are Integrated by OsbZIP23-Associated Super-Enhancer-like Promoter Regions in Rice. Genome Biol. 2024, 25, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masumoto, H.; Hawke, D.; Kobayashi, R.; Verreault, A. A Role for Cell-Cycle-Regulated Histone H3 Lysine 56 Acetylation in the DNA Damage Response. Nature 2005, 436, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, C.; Lucia, M.S.; Hansen, K.C.; Tyler, J.K. CBP/P300-Mediated Acetylation of Histone H3 on Lysine 56. Nature 2009, 459, 113–117, Erratum in Nature 2009, 460, 1164. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, S.; Nodelman, I.M.; Zhou, H.; Tsukiyama, T.; Bowman, G.D.; Zhang, Z. H3K56 Acetylation Regulates Chromatin Maturation Following DNA Replication. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Z.; Nair, D.; Guan, X.; Rastogi, N.; Freitas, M.A.; Parthun, M.R. Sites of Acetylation on Newly Synthesized Histone H4 Are Required for Chromatin Assembly and DNA Damage Response Signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2013, 33, 3286–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opdenakker, K.; Remans, T.; Vangronsveld, J.; Cuypers, A. Mitogen-Activated Protein (MAP) Kinases in Plant Metal Stress: Regulation and Responses in Comparison to Other Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 7828–7853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, C. A Review of Redox Signaling and the Control of MAP Kinase Pathway in Plants. Redox Biol. 2017, 11, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yalowich, J.C.; Hasinoff, B.B. Cadmium Is a Catalytic Inhibitor of DNA Topoisomerase II. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2011, 105, 833–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balali-Mood, M.; Naseri, K.; Tahergorabi, Z.; Khazdair, M.R.; Sadeghi, M. Toxic Mechanisms of Five Heavy Metals: Mercury, Lead, Chromium, Cadmium, and Arsenic. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 643972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, D.W.-K.; Wang, T.; Chandrasekharan, M.B.; Aramayo, R.; Kertbundit, S.; Hall, T.C. Plant SET Domain-Containing Proteins: Structure, Function and Regulation. Biochim. Et. Biophys. Acta—Gene Struct. Expr. 2007, 1769, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerchner, K.M.; Mou, T.-C.; Sun, Y.; Rusnac, D.-V.; Sprang, S.R.; Briknarová, K. The Structure of the Cysteine-Rich Region from Human Histone-Lysine N-Methyltransferase EHMT2 (G9a). J. Struct. Biol. X 2021, 5, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Saad, R.; Ben Romdhane, W.; Wiszniewska, A.; Baazaoui, N.; Bouteraa, M.T.; Chouaibi, Y.; Alfaifi, M.Y.; Kačániová, M.; Čmiková, N.; Ben Hsouna, A.; et al. Rosmarinus officinalis L. Essential Oil Enhances Salt Stress Tolerance of Durum Wheat Seedlings through ROS Detoxification and Stimulation of Antioxidant Defense. Protoplasma 2024, 261, 1207–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaouani, K.; Karmous, I.; Ostrowski, M.; Ferjani, E.E.; Jakubowska, A.; Chaoui, A. Cadmium Effects on Embryo Growth of Pea Seeds during Germination: Investigation of the Mechanisms of Interference of the Heavy Metal with Protein Mobilization-Related Factors. J. Plant Physiol. 2018, 226, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sfaxi-Bousbih, A.; Chaoui, A.; Ferjani, E.E. Cadmium Impairs Mineral and Carbohydrate Mobilization during the Germination of Bean Seeds. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2010, 73, 1123–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Osuna, A.; Calatrava, V.; Galvan, A.; Fernandez, E.; Llamas, A. Identification of the MAPK Cascade and Its Relationship with Nitrogen Metabolism in the Green Alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Li, X.; Guo, C.; Ma, C.; Duan, W.; Lu, W.; Xiao, K. Characterization and Expression Analysis of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Cascade Genes in Wheat Subjected to Phosphorus and Nitrogen Deprivation, High Salinity, and Drought. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2015, 24, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tan, N.W.K.; Chung, F.Y.; Yamaguchi, N.; Gan, E.-S.; Ito, T. Transcriptional Regulators of Plant Adaptation to Heat Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucholt, P.; Sjödin, P.; Weih, M.; Rönnberg-Wästljung, A.C.; Berlin, S. Genome-Wide Transcriptional and Physiological Responses to Drought Stress in Leaves and Roots of Two Willow Genotypes. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 244, Erratum in BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 285. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-015-0665-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, L.; Huang, S.C.; Wise, A.; Castanon, R.; Nery, J.R.; Chen, H.; Watanabe, M.; Thomas, J.; Bar-Joseph, Z.; Ecker, J.R. A Transcription Factor Hierarchy Defines an Environmental Stress Response Network. Science 2016, 354, aag1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovalchuk, I.; Titov, V.; Hohn, B.; Kovalchuk, O. Transcriptome Profiling Reveals Similarities and Differences in Plant Responses to Cadmium and Lead. Mutat. Res. Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2005, 570, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kintlová, M.; Vrána, J.; Hobza, R.; Blavet, N.; Hudzieczek, V. Transcriptome Response to Cadmium Exposure in Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 629089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, R.F.; Hershey, J.W.B. Translational Repression by Chemical Inducers of the Stress Response Occurs by Different Pathways. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1987, 256, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinnebusch, A.G. The eIF-2α Kinases: Regulators of Protein Synthesis in Starvation and Stress. Semin. Cell Biol. 1994, 5, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.P.; Leach, J.E. Abiotic and Biotic Stresses Induce a Core Transcriptome Response in Rice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firmino, J.P.; Fernández-Alacid, L.; Vallejos-Vidal, E.; Salomón, R.; Sanahuja, I.; Tort, L.; Ibarz, A.; Reyes-López, F.E.; Gisbert, E. Carvacrol, Thymol, and Garlic Essential Oil Promote Skin Innate Immunity in Gilthead Seabream (Sparus aurata) Through the Multifactorial Modulation of the Secretory Pathway and Enhancement of Mucus Protective Capacity. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 633621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünyayar, S.; Çelik, A.; Çekiç, F.Ö.; Gözel, A. Cadmium-Induced Genotoxicity, Cytotoxicity and Lipid Peroxidation in Allium sativum and Vicia faba. Mutagenesis 2006, 21, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souguir, D.; Ferjani, E.; Ledoigt, G.; Goupil, P. Sequential Effects of Cadmium on Genotoxicity and Lipoperoxidation in Vicia faba Roots. Ecotoxicology 2011, 20, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żabka, A.; Winnicki, K.; Polit, J.T.; Wróblewski, M.; Maszewski, J. Cadmium (II)-Induced Oxidative Stress Results in Replication Stress and Epigenetic Modifications in Root Meristem Cell Nuclei of Vicia faba. Cells 2021, 10, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żabka, A.; Polit, J.T.; Maszewski, J. Inter- and Intrachromosomal Asynchrony of Cell Division Cycle Events in Root Meristem Cells of Allium cepa: Possible Connection with Gradient of Cyclin B-like Proteins. Plant Cell Rep. 2010, 29, 845–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żabka, A.; Polit, J.T.; Maszewski, J. DNA Replication Stress Induces Deregulation of the Cell Cycle Events in Root Meristems of Allium cepa. Ann. Bot. 2012, 110, 1581–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesraoui, S.; Andrés, M.; Berrocal-Lobo, M.; Soudani, S.; Gonzalez-Coloma, A. Direct and Indirect Effects of Essential Oils for Sustainable Crop Protection. Plants 2022, 11, 2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayllón-Gutiérrez, R.; Díaz-Rubio, L.; Montaño-Soto, M.; Haro-Vázquez, M.D.P.; Córdova-Guerrero, I. Applications of Plant Essential Oils in Pest Control and Their Encapsulation for Controlled Release: A Review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gocek-Szczurtek, N.; Żabka, A.; Wróblewski, M.; Polit, J.T. Stabilization of the MAPK–Epigenetic Signaling Axis Underlies the Protective Effect of Thyme Oil Against Cadmium Stress in Root Meristem Cells of Vicia faba. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010208

Gocek-Szczurtek N, Żabka A, Wróblewski M, Polit JT. Stabilization of the MAPK–Epigenetic Signaling Axis Underlies the Protective Effect of Thyme Oil Against Cadmium Stress in Root Meristem Cells of Vicia faba. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):208. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010208

Chicago/Turabian StyleGocek-Szczurtek, Natalia, Aneta Żabka, Mateusz Wróblewski, and Justyna T. Polit. 2026. "Stabilization of the MAPK–Epigenetic Signaling Axis Underlies the Protective Effect of Thyme Oil Against Cadmium Stress in Root Meristem Cells of Vicia faba" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010208

APA StyleGocek-Szczurtek, N., Żabka, A., Wróblewski, M., & Polit, J. T. (2026). Stabilization of the MAPK–Epigenetic Signaling Axis Underlies the Protective Effect of Thyme Oil Against Cadmium Stress in Root Meristem Cells of Vicia faba. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010208