Potential Physiological and Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Low Viability of Gynogenetic WW-Type Super-Female Sterlet (Acipenser ruthenus)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

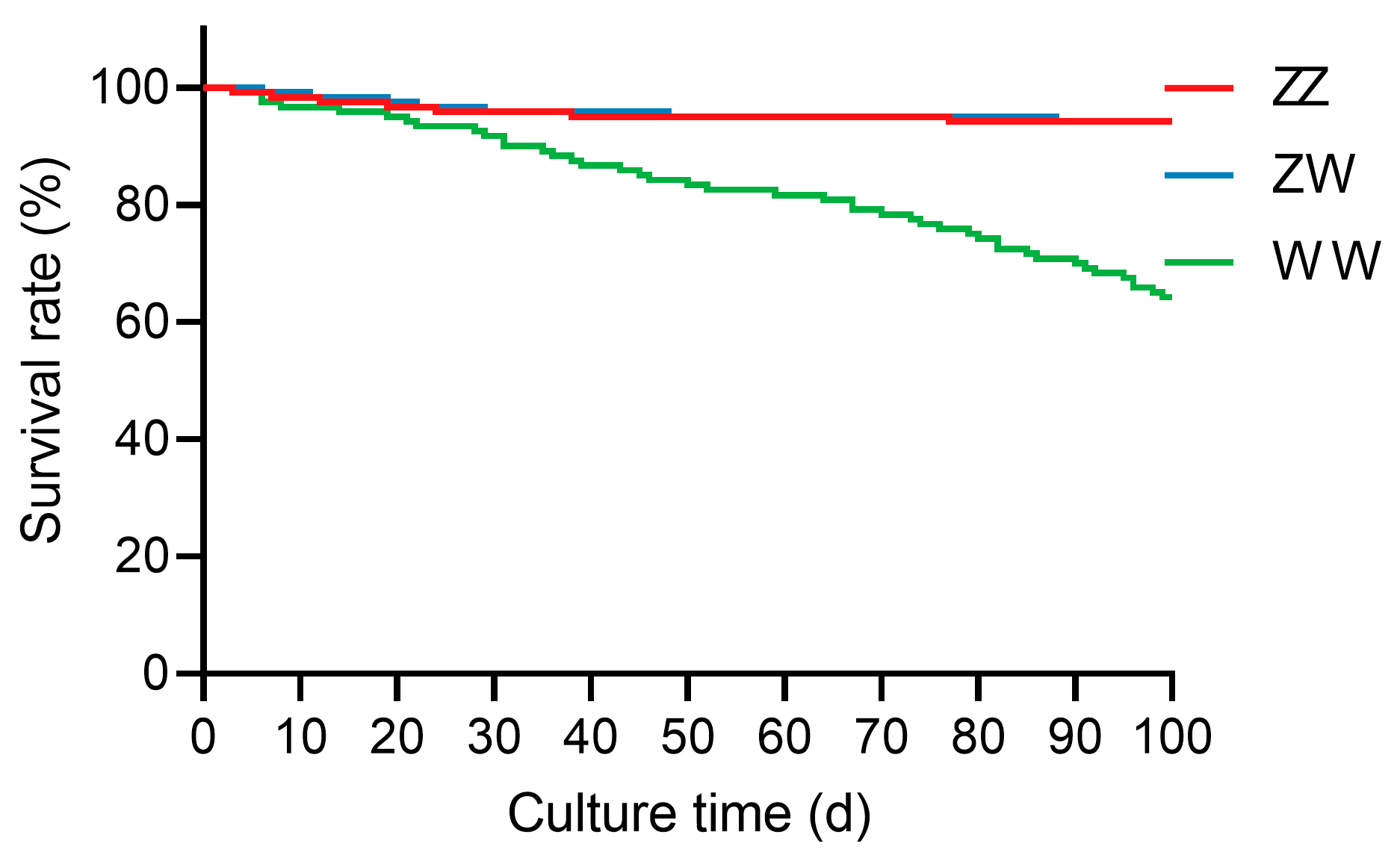

2.1. Survival Rate of Juvenile Sterlet with Different Sex Genotypes

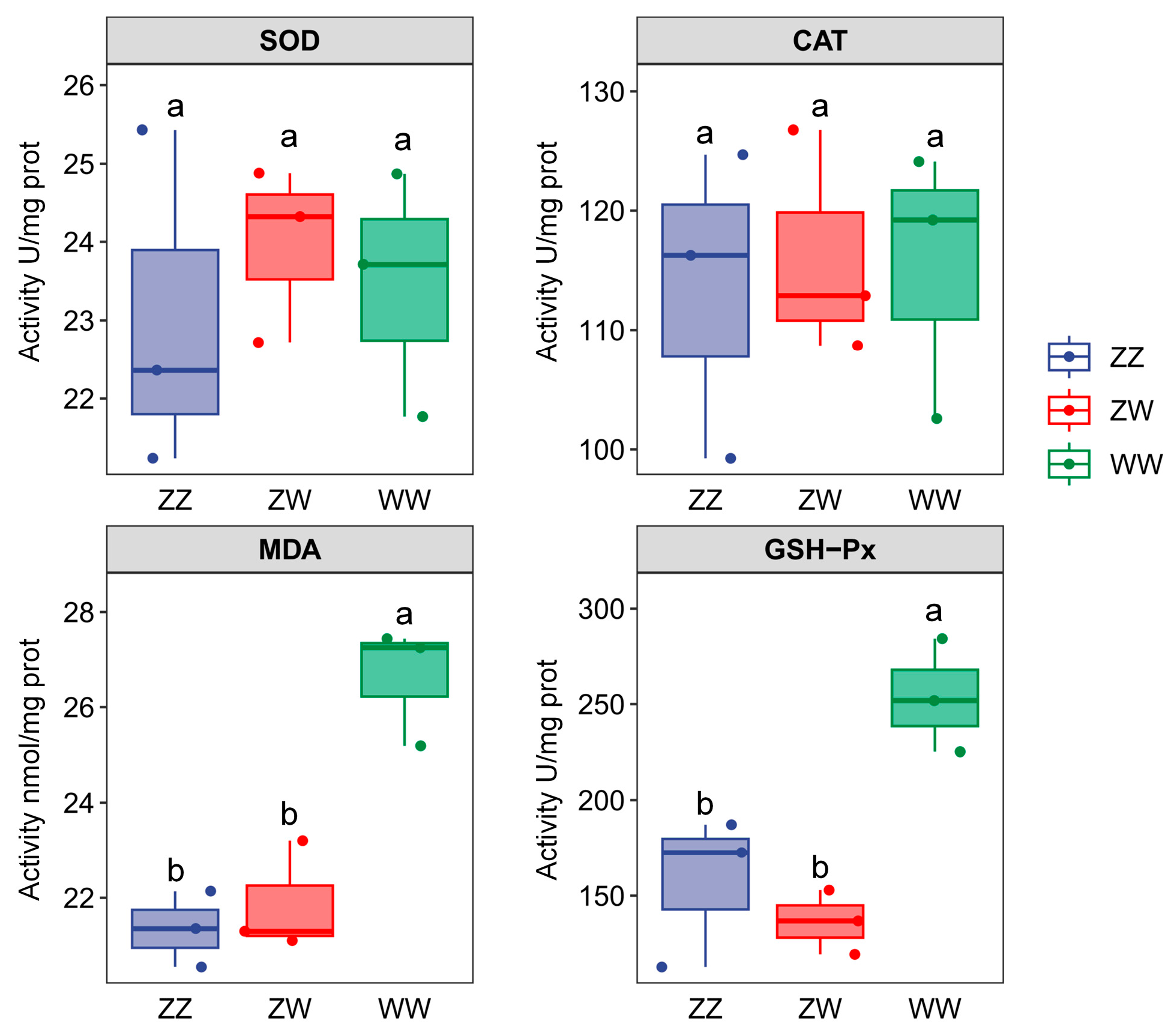

2.2. Antioxidant Indices of Juvenile Sterlet with Different Sex Genotypes

2.3. Quality Assessment of Transcriptome Sequencing of Gonadal Tissues

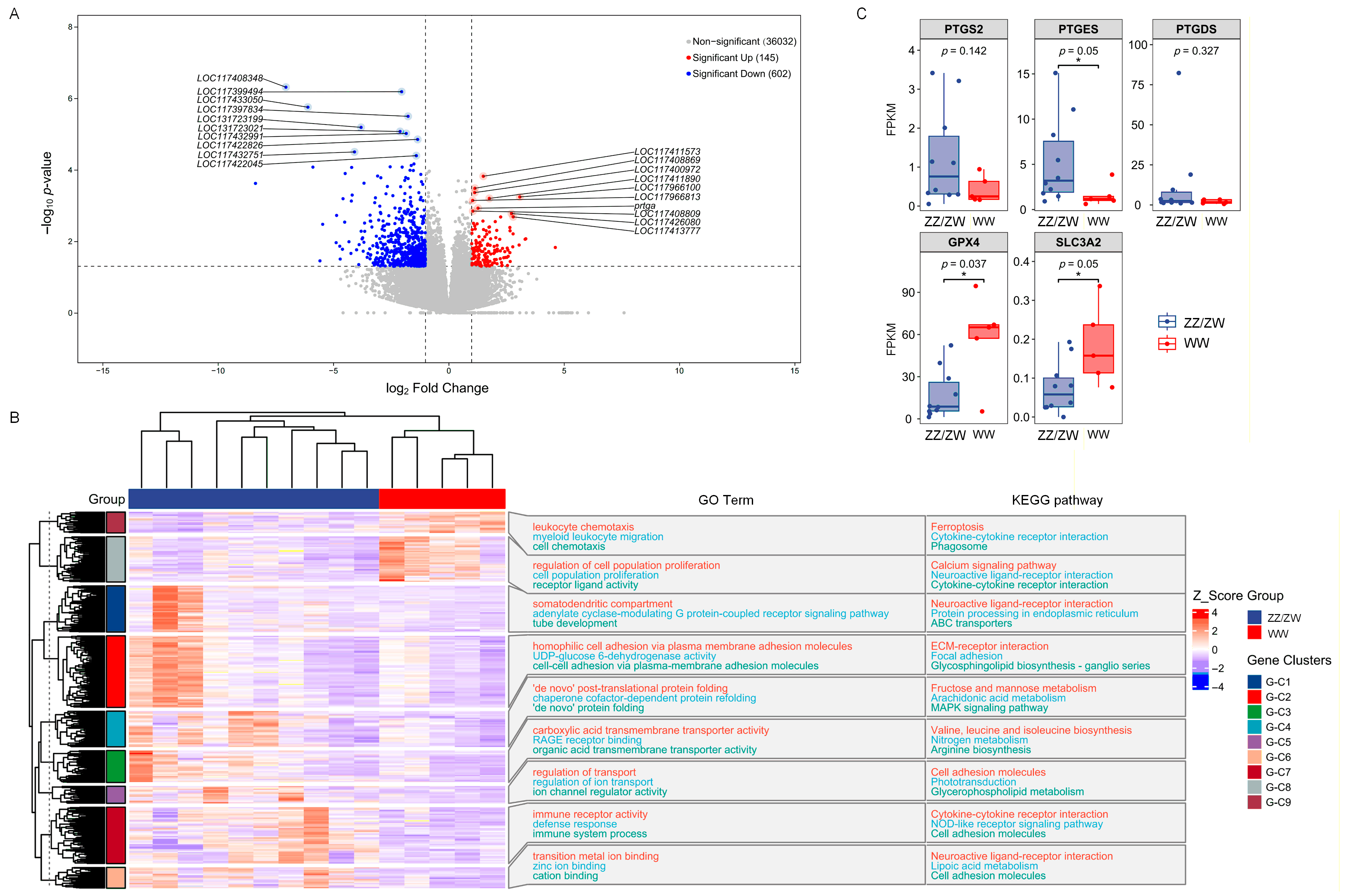

2.4. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes Between Normal Males/Females and Super-Females

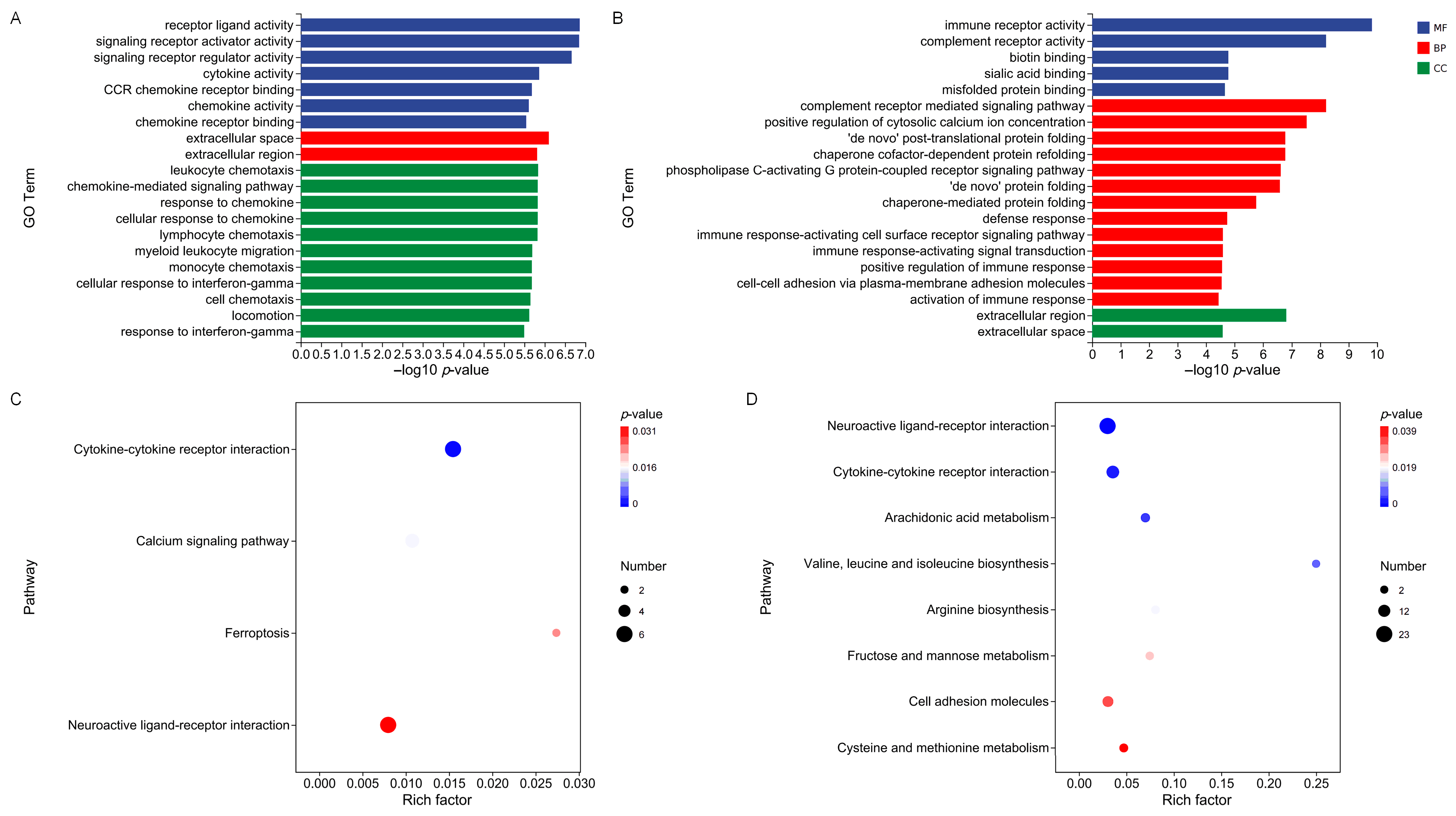

2.5. GO and KEGG Enrichment Analyses of Differentially Expressed Genes

3. Discussion

3.1. Significant Differences in Physiological State and Gene Expression Patterns Between Normal Male/Female and Super-Female Sterlet

3.2. Potential Involvement of Ferroptosis Associated with Disrupted Arachidonic Acid Metabolism in the Reduced Viability of Super-Female Sterlet

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Materials

4.2. Experimental Design and Sample Collection

4.3. Determination of Antioxidant Indices

4.4. RNA Extraction, Library Construction, and De Novo Transcriptome Sequencing

4.5. Quality Control, Assembly, and Functional Annotation

4.6. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes and Enrichment Analysis

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dudu, A.; Georgescu, S.E. Exploring the multifaceted potential of endangered sturgeon: Caviar, meat and by-product benefits. Animals 2024, 14, 2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wuertz, S.; Güralp, H.; Pšenička, M.; Chebanov, M. Sex determination in sturgeon. In Sex Control in Aquaculture; Wang, H., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 645–668. [Google Scholar]

- Laczynska, B.; Demska-Zakes, K.; Siddique, M.A.M.; Fopp-Bayat, D. Meiotic gynogenesis affects the individual and gonadal development in sterlet Acipenser ruthenus. Aquac. Res. 2020, 51, 3623–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fopp-Bayat, D.; Szadkowska, J.; Szczepkowski, M.; Szczepkowska, B.; Naumowicz, K. Gonadal analysis in the F1 progeny of a gynogenetic Siberian sturgeon Acipenser baerii female. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2020, 221, 106548, Correction in Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 236, 107031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, M.H.; Hallajian, A. Study of sex determination system in ship sturgeon Acipenser nudiventris using meiotic gynogenesis. Aquac. Int. 2014, 22, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, S.R.; Matsuoka, M.; Reith, M.; Martin-Robichaud, D.; Benfey, T. Gynogenesis and sex determination in shortnose sturgeon, Acipenser brevirostrum. Aquaculture 2006, 253, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoto, N.; Maebayashi, M.; Adachi, S.; Arai, K.; Yamauchi, K. Sex ratios of triploids and gynogenetic diploids induced in the hybrid sturgeon, the bester (Huso huso × Acipenser ruthenus). Aquaculture 2005, 245, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinami, R.; Ineno, T. First evidence of WW superfemale for hybrid sturgeon, the bester (Huso huso × Acipenser ruthenus). Aquaculture 2025, 596, 741808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komen, J.; Wiegertjes, G.F.; van Ginneken, V.J.T.; Eding, E.; Richter, C. Gynogenesis in common carp (Cyprinus carpio): III. The effects of inbreeding on gonadal development of heterozygous and homozygous gynogenetic offspring. Aquaculture 1992, 104, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagiełło, K.; Zalewski, T.; Dobosz, S.; Michalik, O.; Ocalewicz, K. High rate of deformed larvae among gynogenetic brown trout (Salmo trutta m. fario) doubled haploids. Biomed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 2975187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rożyński, R.; Kuciński, M.; Dobosz, S.; Ocalewicz, K. Successful application of UV-irradiated rainbow trout spermatozoa to induce gynogenetic development of the European grayling (Thymallus thymallus). Aquaculture 2023, 574, 739720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubler, M.J.; Kennedy, A.J. Role of lipids in the metabolism and activation of immune cells. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 34, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Shi, X.; Pei, C.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Li, C.; Kong, X. The role of ferroptosis in fish inflammation. Rev. Aquac. 2023, 15, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Kim, W.K.; Bae, K.-H.; Lee, S.C.; Lee, E.-W. Lipid metabolism and ferroptosis. Biology 2021, 10, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-L.; Ji, X.-S.; Shao, C.-W.; Li, W.-L.; Yang, J.-F.; Liang, Z.; Liao, X.-L.; Xu, G.-B.; Xu, Y.; Song, W.-T. Induction of mitogynogenetic diploids and identification of WW super-female using sex-specific SSR markers in half-smooth tongue sole (Cynoglossus semilaevis). Mar. Biotechnol. 2012, 14, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manan, H.; Hidayati, A.B.N.; Lyana, N.A.A.; Amin-Safwan, A.; Ma, H.; Kasan, N.A.; Ikhwanuddin, M. A review of gynogenesis manipulation in aquatic animals. Aquac. Fish. 2022, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, J.; Tan, H.; Luo, L.; Cui, J.; Hu, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, Q.; Hu, F.; Tang, C.; et al. Asymmetric expression patterns reveal a strong maternal effect and dosage compensation in polyploid hybrid fish. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, X.; Li, X.; Deng, S.; Zhang, B.; Xiao, G.; Xu, Y.; Brennan, C.; Benjakul, S.; Ma, L. How lipids, as important endogenous nutrient components, affect the quality of aquatic products: An overview of lipid peroxidation and the interaction with proteins. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Guo, M.; Fang, D.; Mei, J.; Xie, J. Analysis of acute nitrite exposure on physiological stress response, oxidative stress, gill tissue morphology and immune response of large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea). Animals 2022, 12, 1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuphal, B.; Sathoria, P.; Rai, U.; Roy, B. Crosstalk between reproductive and immune systems: The teleostean perspective. J. Fish Biol. 2023, 102, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, J.H.; Dixon, B.; Whitehouse, L.M. The intersection of stress, sex and immunity in fishes. Immunogenetics 2021, 73, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrier, A.L.; Yamada, K.M. Cell–matrix adhesion. J. Cell. Physiol. 2007, 213, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X.; Cheng, Z.; He, B.; Liu, H.; Liu, M.; Hu, J.; Lei, L.; Wang, L.; Bai, Y. Ferroptosis in aquaculture research. Aquaculture 2021, 541, 736760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Zhang, D.; Li, J.; Li, Q.; Pang, Y. Lamprey immune protein triggers the ferroptosis pathway during zebrafish embryonic development. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 20, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, S.; Sun, B.; Cao, D.; Sun, Z.; Lv, W.; Ma, B.; Zhang, Y. Chronic heat stress caused lipid metabolism disorder and tissue injury in the liver of Huso dauricus via oxidative-stress-mediated ferroptosis. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Han, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, B. Combined impacts of acute heat stress on the histology, antioxidant activity, immunity, and intestinal microbiota of wild female burbot (Lota lota) in winter. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tallima, H.; El Ridi, R. Arachidonic acid: Physiological roles and potential health benefits. J. Adv. Res. 2018, 11, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, V.S.; Hafez, E.A.A. Synopsis of arachidonic acid metabolism: A review. J. Adv. Res. 2018, 11, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaschler, M.M.; Stockwell, B.R. Lipid peroxidation in cell death. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 482, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanner, J.; Shpaizer, A.; Tirosh, O. Ferroptosis: The initiation process of lipid peroxidation in muscle food. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poltorack, C.D.; Dixon, S.J. Understanding the role of cysteine in ferroptosis: Progress & paradoxes. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, H.; Matsuoka, M.; Kumagai, T.; Sakamoto, T.; Koumura, T. Lipid peroxidation-dependent cell death regulated by GPX4 and ferroptosis. In Apoptotic and Non-Apoptotic Cell Death; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 143–170. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, C.; Xing, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Jin, X.; Tian, M.; Ba, X.; Hao, F. Cysteine and homocysteine can be exploited by GPX4 in ferroptosis inhibition independent of GSH synthesis. Redox Biol. 2024, 69, 102999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabherr, M.G.; Haas, B.J.; Yassour, M.; Levin, J.Z.; Thompson, D.A.; Amit, I.; Adiconis, X.; Fan, L.; Raychowdhury, R.; Zeng, Q.D.; et al. Trinity: Reconstructing a full-length transcriptome without a genome from RNA-Seq data. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Williams, B.A.; Pertea, G.; Mortazavi, A.; Kwan, G.; Van Baren, M.J.; Salzberg, S.L.; Wold, B.J.; Pachter, L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, A.; Pachter, L. Streaming fragment assignment for real-time analysis of sequencing experiments. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Raw Reads (M) | Raw Bases (Gb) | Valid Bases (%) | GC (%) | Q20 (%) | Q30 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZZ-1 | 43.14 | 6.51 | 95.57 | 45.04 | 98.74 | 95.54 |

| ZZ-2 | 39.21 | 5.92 | 95.59 | 44.64 | 98.71 | 95.49 |

| ZZ-3 | 42.08 | 6.35 | 95.56 | 45.06 | 98.72 | 95.54 |

| ZZ-4 | 36.89 | 5.57 | 95.57 | 45.49 | 98.77 | 95.58 |

| ZZ-5 | 56.21 | 8.49 | 95.59 | 45.80 | 98.57 | 95.10 |

| ZW-1 | 39.83 | 6.01 | 95.58 | 46.27 | 98.66 | 95.27 |

| ZW-2 | 38.61 | 5.83 | 95.57 | 45.34 | 98.80 | 95.70 |

| ZW-3 | 40.23 | 6.07 | 95.80 | 44.90 | 98.84 | 95.88 |

| ZW-4 | 36.61 | 5.53 | 95.59 | 44.95 | 98.68 | 95.44 |

| ZW-5 | 40.63 | 6.13 | 95.58 | 45.21 | 98.59 | 95.24 |

| WW-1 | 41.70 | 6.30 | 95.58 | 44.84 | 98.72 | 95.44 |

| WW-2 | 41.68 | 6.29 | 95.58 | 44.07 | 98.68 | 95.45 |

| WW-3 | 46.92 | 7.09 | 96.55 | 44.54 | 98.71 | 95.48 |

| WW-4 | 49.91 | 7.54 | 95.61 | 44.94 | 98.85 | 95.83 |

| WW-5 | 40.20 | 6.07 | 95.58 | 44.59 | 98.72 | 95.54 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, R.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Che, H.; Cao, D.; Sun, Z.; Ma, B.; Zhang, Y. Potential Physiological and Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Low Viability of Gynogenetic WW-Type Super-Female Sterlet (Acipenser ruthenus). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010207

Wang R, Li Y, Zhang Y, Wang S, Che H, Cao D, Sun Z, Ma B, Zhang Y. Potential Physiological and Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Low Viability of Gynogenetic WW-Type Super-Female Sterlet (Acipenser ruthenus). International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):207. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010207

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Ruoyu, Yutao Li, Yining Zhang, Sihan Wang, Hongrui Che, Dingchen Cao, Zhipeng Sun, Bo Ma, and Ying Zhang. 2026. "Potential Physiological and Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Low Viability of Gynogenetic WW-Type Super-Female Sterlet (Acipenser ruthenus)" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010207

APA StyleWang, R., Li, Y., Zhang, Y., Wang, S., Che, H., Cao, D., Sun, Z., Ma, B., & Zhang, Y. (2026). Potential Physiological and Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Low Viability of Gynogenetic WW-Type Super-Female Sterlet (Acipenser ruthenus). International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010207