Impact of Low-Dose CT Radiation on Gene Expression and DNA Integrity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Patient Characteristics

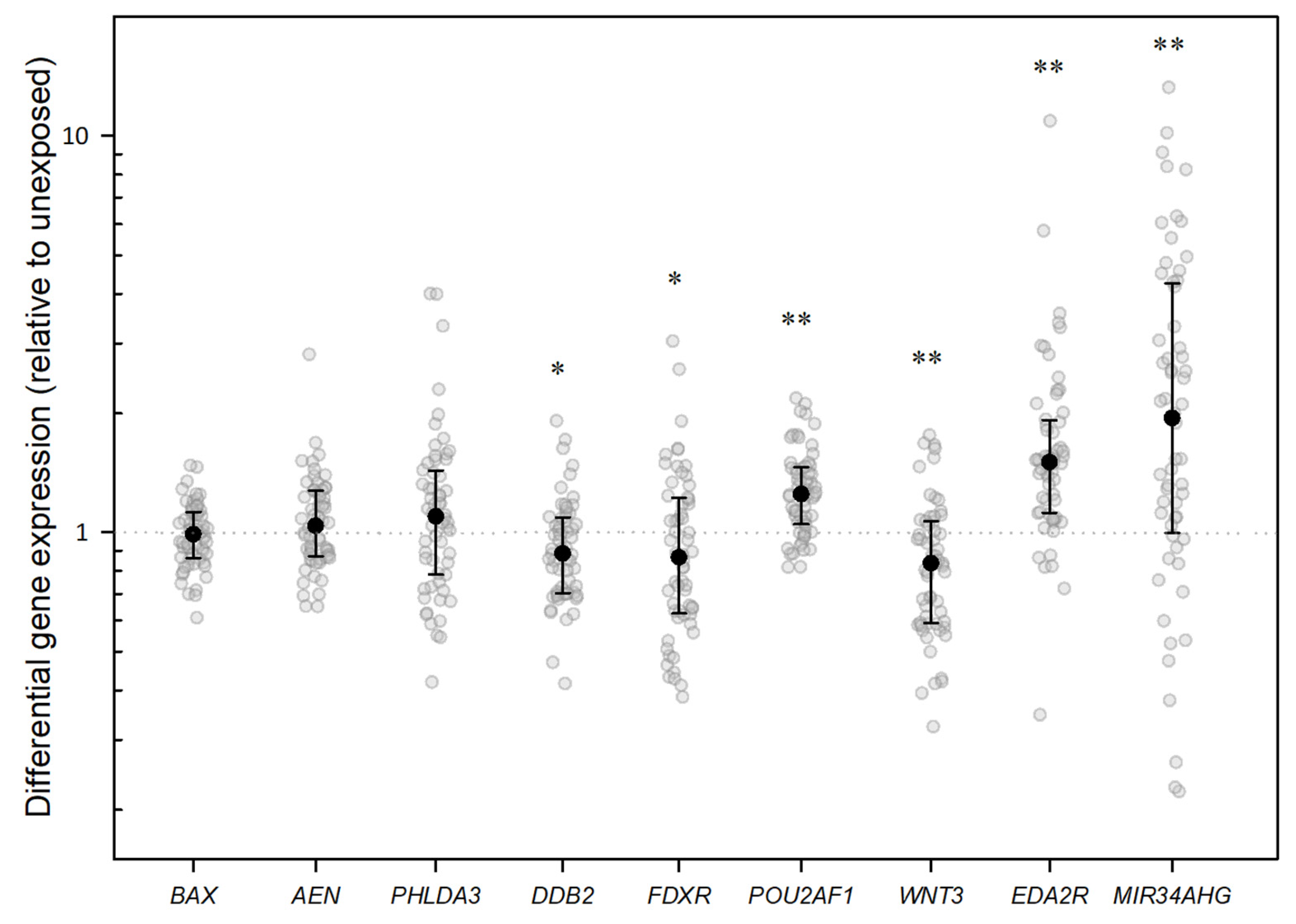

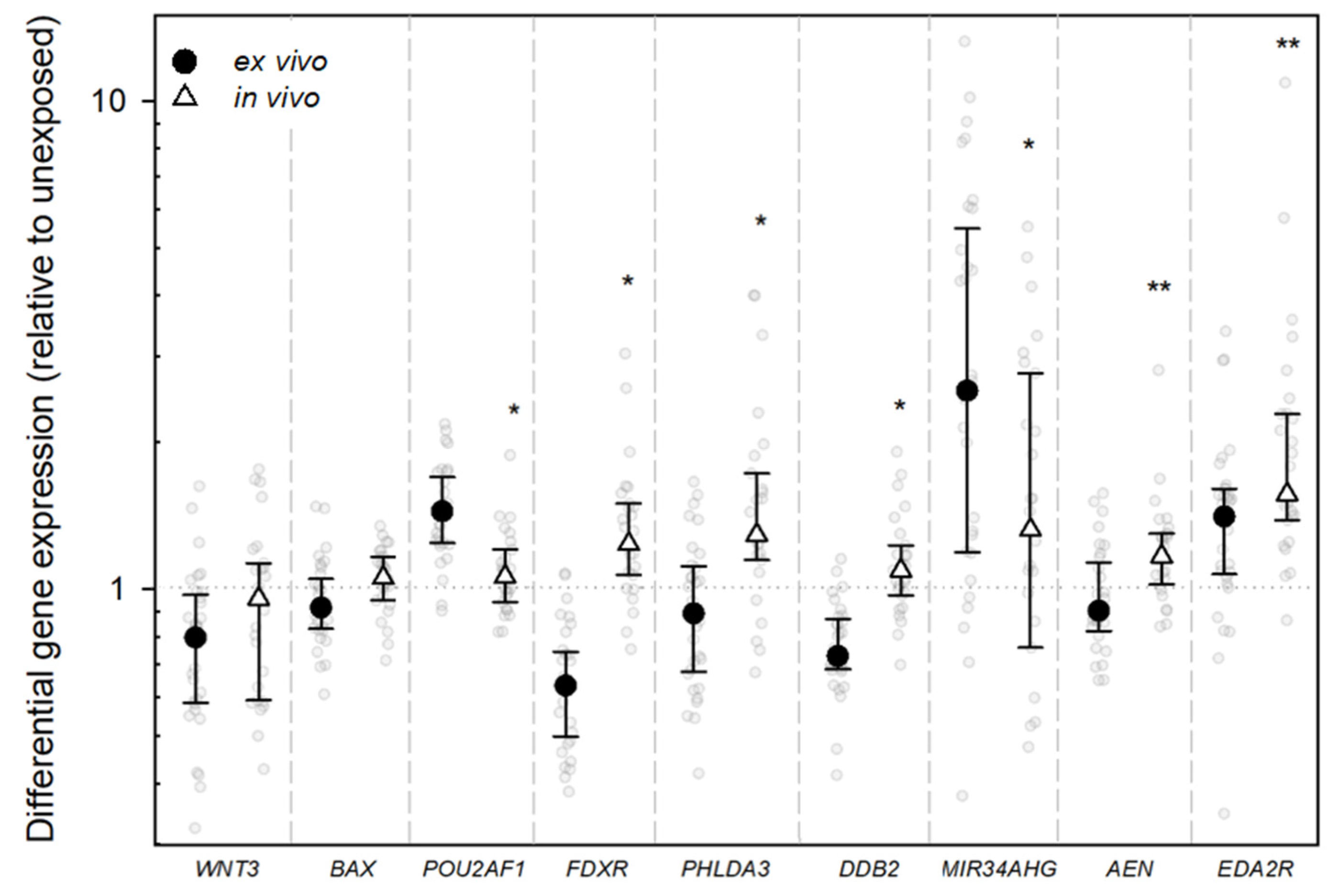

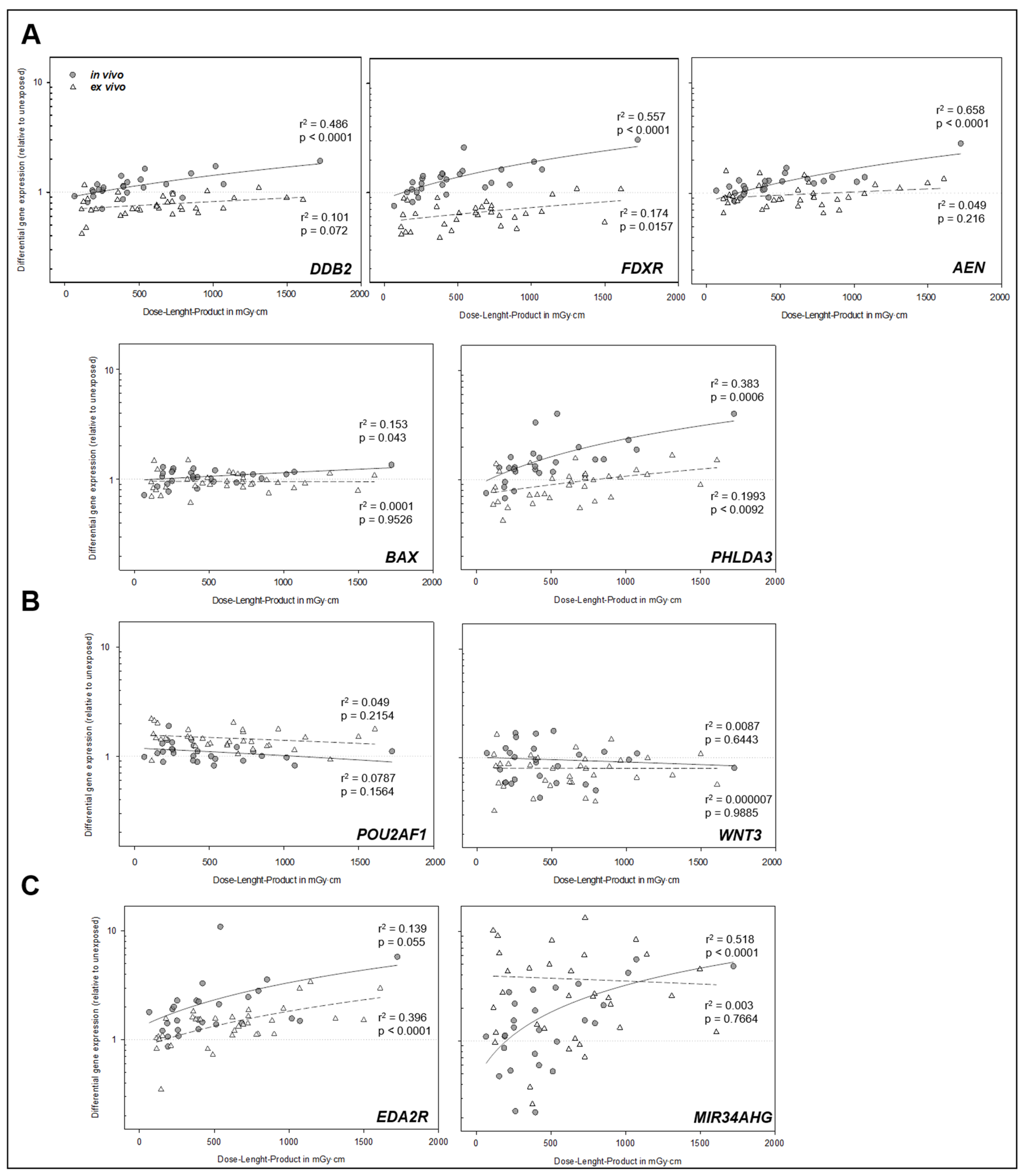

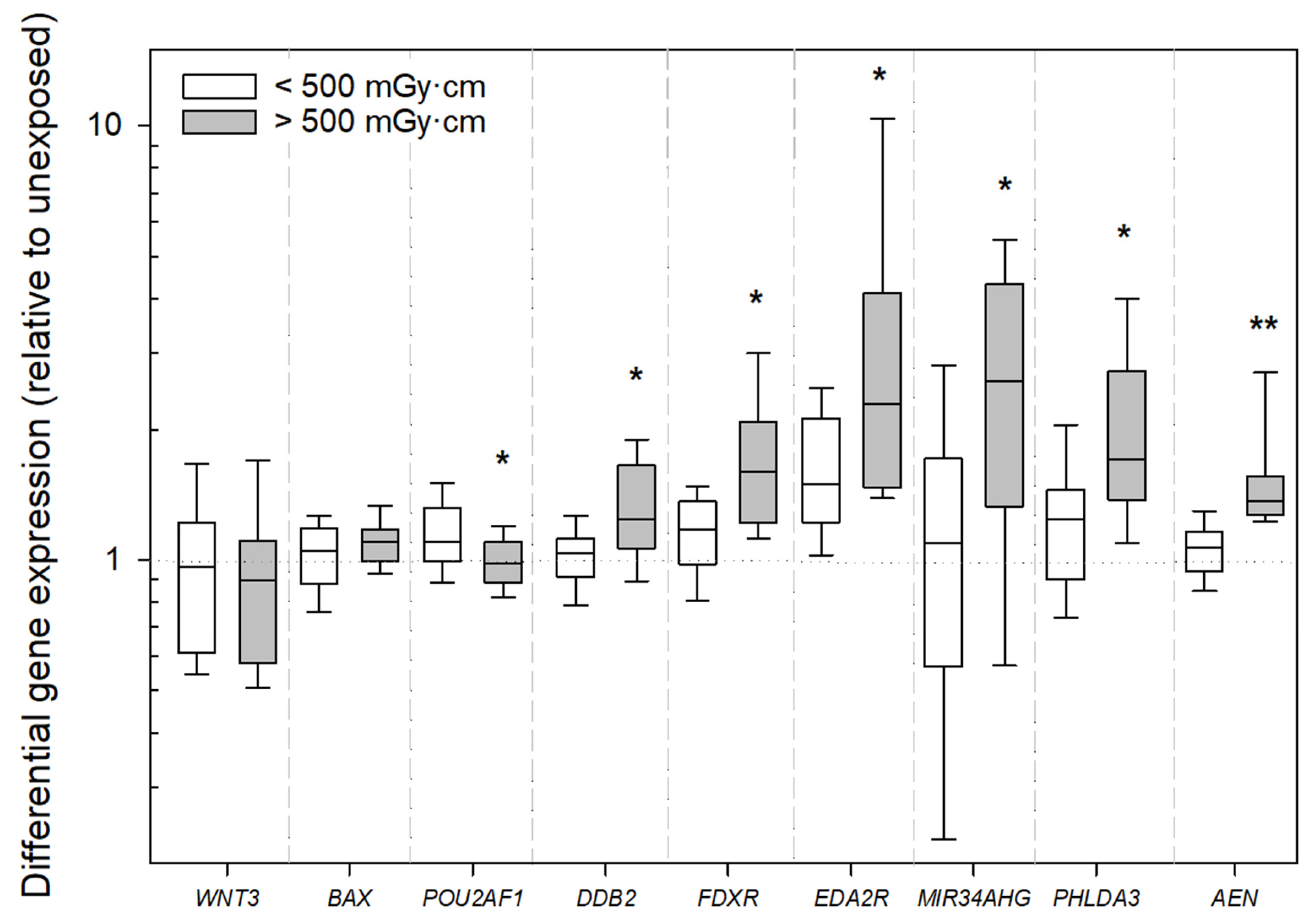

2.2. Gene Expression Analysis

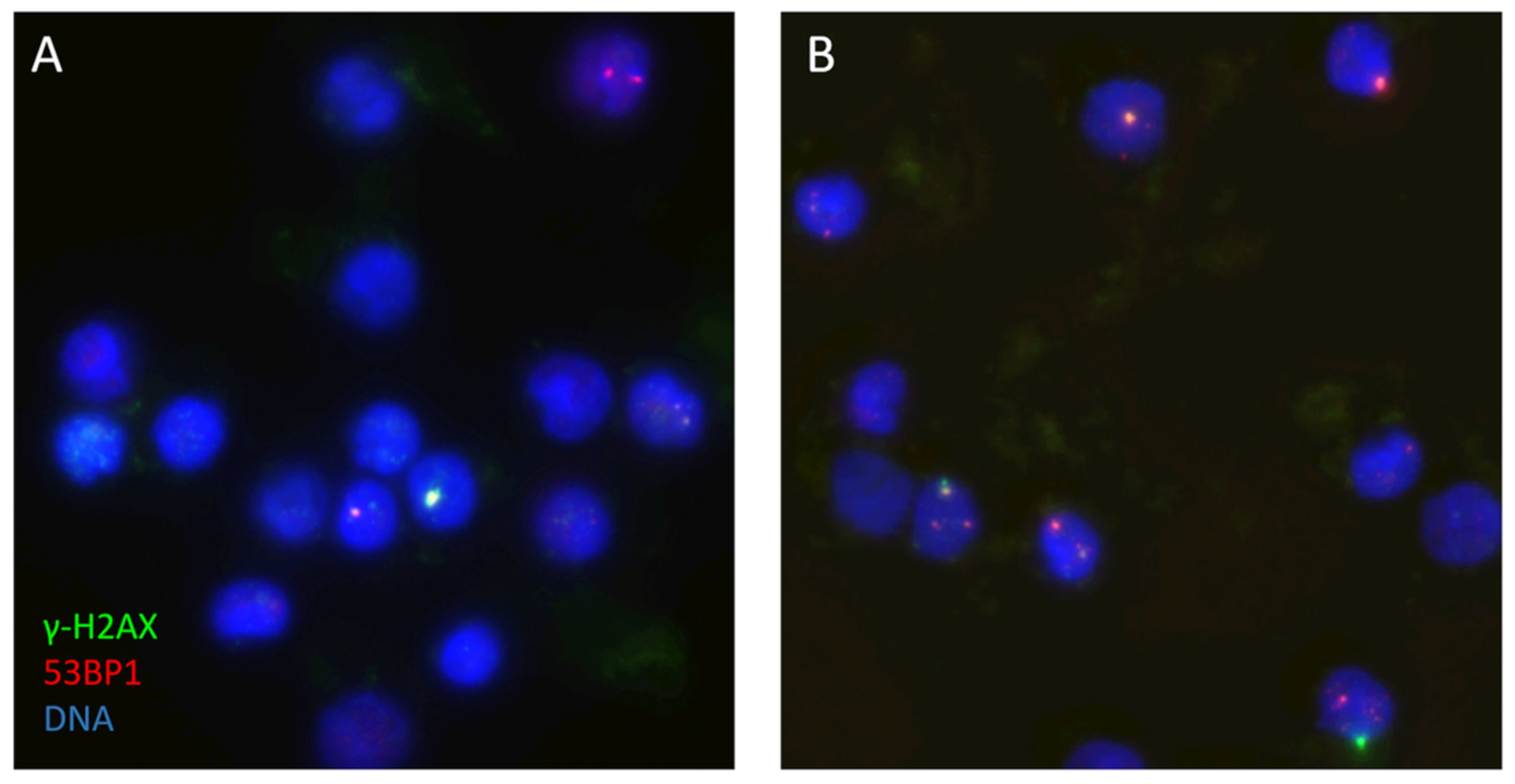

2.3. DNA Double-Strand Break Analysis

3. Discussion

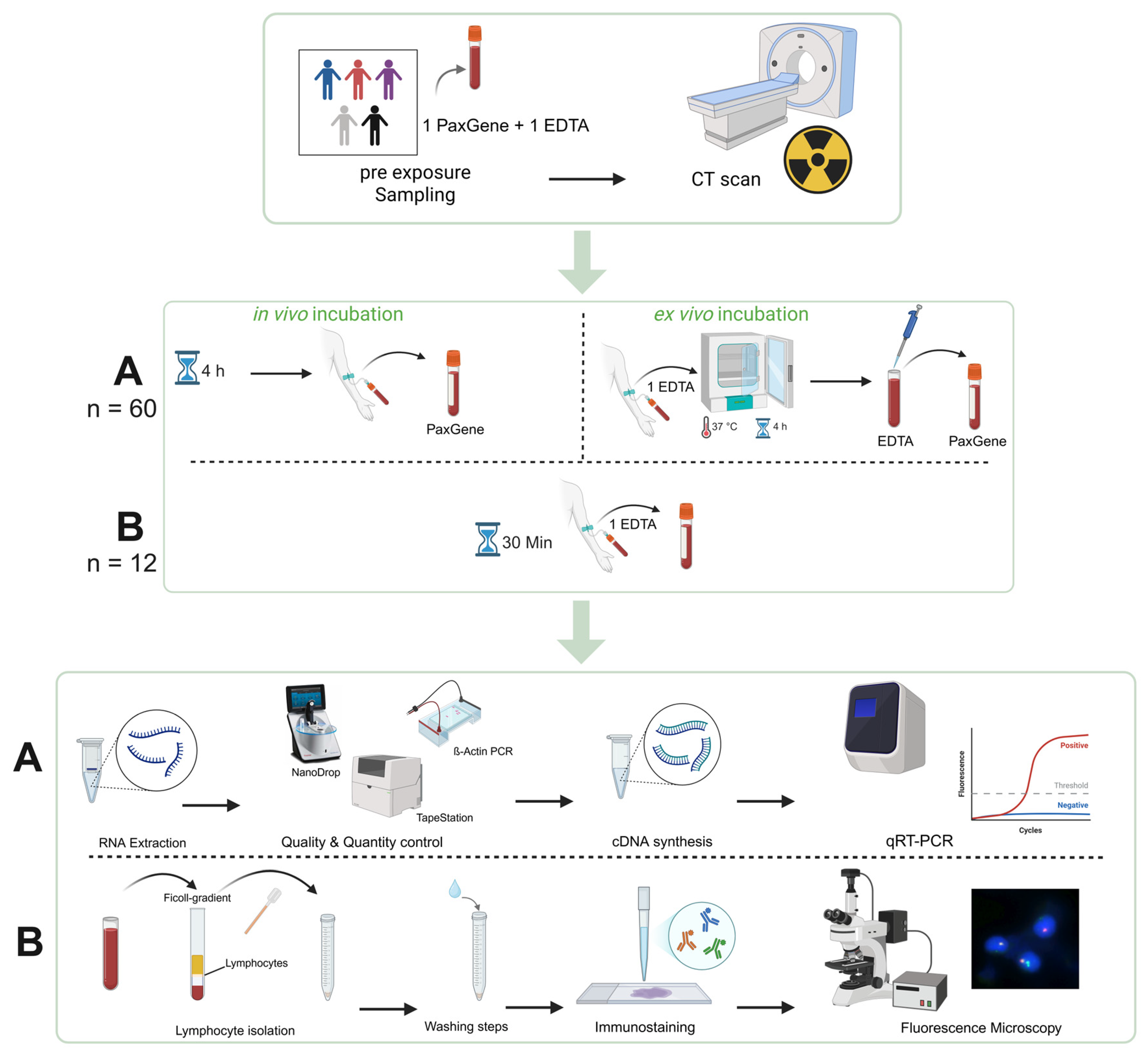

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. CT Imaging

4.2. Sample Selection

4.3. RNA Extraction

4.4. Quantity and Quality Control

4.5. Quantitative Real-Time Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

4.6. Immunostaining and DNA DSB Focus Analysis

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| qRT-PCR | Quick Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| DLP | Dose–Length Product |

| LNT | Linear No-Threshold |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Patient Number | Differential Gene Expression Normalized to PUM1 | Dose–Length Product [mGy·cm] | Estimated Effective Dose [mSv] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene of Interest | |||||||||||

| DDB2 | FDXR | POU2AF1 | WNT3 | BAX | AEN | EDA2R | MIR34AHG | PHLDA3 | |||

| 1 | 1.72 | 1.91 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 1.11 | 1.26 | 1.57 | 4.17 | 2.30 | 1020 | 15.30 |

| 2 | 1.48 | 1.18 | 1.00 | 1.13 | 1.01 | 1.40 | 3.57 | 2.11 | 1.53 | 854 | 12.81 |

| 3 | 1.23 | 1.32 | 1.10 | 0.43 | 1.04 | 1.30 | 3.29 | 1.26 | 1.58 | 423 | 6.35 |

| 4 | 1.17 | 1.00 | 1.40 | 1.11 | 0.90 | 1.30 | 1.90 | 2.77 | 1.27 | 221 | 3.32 |

| 5 | 1.13 | 1.18 | 1.00 | 1.66 | 1.02 | 1.17 | 1.25 | 1.89 | 1.24 | 396 | 5.54 |

| 6 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 1.06 | 0.78 | 0.86 | 1.14 | 1.21 | 0.48 | 1.29 | 155 | 2.17 |

| 7 | 1.91 | 3.04 | 1.10 | 0.81 | 1.35 | 2.81 | 5.77 | 4.79 | 4.00 | 1725 | 24.15 |

| 8 | 1.09 | 1.57 | 0.82 | 0.58 | 0.95 | 1.52 | 2.12 | 3.05 | 1.44 | 533 | 8.00 |

| 9 | 1.04 | 1.34 | 1.14 | 1.68 | 1.20 | 1.02 | 1.23 | 2.18 | 1.29 | 259 | 3.89 |

| 10 | 0.73 | 0.61 | 1.35 | 0.68 | 0.89 | 0.77 | 1.11 | 2.53 | 0.98 | 784 | 11.76 |

| 11 | 0.88 | 0.96 | 1.48 | 0.99 | 0.91 | 1.18 | 3.38 | 6.09 | 1.11 | 1145 | 17.18 |

| 12 | 0.88 | 1.62 | 1.10 | 0.50 | 1.10 | 1.28 | 2.81 | 1.45 | 1.53 | 797 | 11.96 |

| 13 | 1.03 | 1.07 | 1.31 | 0.59 | 1.05 | 0.85 | 1.41 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 188 | 2.82 |

| 14 | 1.02 | 1.21 | 1.34 | 0.63 | 0.96 | 1.15 | 2.29 | 1.32 | 0.78 | 254 | 3.81 |

| 15 | 0.70 | 0.44 | 1.44 | 0.61 | 0.92 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 1.29 | 0.73 | 458 | 6.87 |

| 16 | 1.00 | 0.82 | 1.10 | 1.23 | 1.13 | 0.84 | 1.06 | 1.09 | 0.68 | 192 | 2.88 |

| 17 | 1.01 | 0.63 | 1.76 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 1.93 | 1.32 | 1.04 | 964 | 14.46 |

| 18 | 1.05 | 0.89 | 1.88 | 0.58 | 0.77 | 0.90 | 2.01 | 0.53 | 1.61 | 231 | 3.47 |

| 19 | 0.88 | 0.53 | 1.50 | 1.08 | 0.78 | 1.23 | 1.51 | 4.51 | 0.89 | 1501 | 22.52 |

| 20 | 0.62 | 0.66 | 1.66 | 0.42 | 0.84 | 0.92 | 1.64 | 0.71 | 1.03 | 729 | 10.94 |

| 21 | 1.18 | 1.63 | 0.82 | 1.09 | 1.16 | 1.39 | 1.48 | 5.53 | 1.88 | 1074 | 16.11 |

| 22 | 0.97 | 1.23 | 0.91 | 0.57 | 1.10 | 1.22 | 2.46 | 1.53 | 1.08 | 729 | 10.94 |

| 23 | 1.63 | 2.58 | 0.94 | 0.84 | 1.20 | 1.69 | 10.91 | 0.98 | 4.00 | 542 | 8.13 |

| 24 | 0.70 | 0.62 | 1.35 | 0.59 | 1.17 | 0.86 | 1.21 | 4.32 | 0.95 | 637 | 9.56 |

| 25 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 1.28 | 0.67 | 0.86 | 0.76 | 1.09 | 0.83 | 1.06 | 622 | 9.33 |

| 26 | 1.17 | 1.11 | 1.21 | 1.06 | 0.93 | 1.34 | 1.42 | 3.31 | 1.98 | 686 | 10.29 |

| 27 | 0.70 | 0.63 | 1.45 | 0.87 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 4.28 | 0.55 | 212 | 2.97 |

| 28 | 1.40 | 1.39 | 1.41 | 1.21 | 1.14 | 1.07 | 2.29 | 2.92 | 1.73 | 383 | 5.36 |

| 29 | 0.64 | 0.46 | 1.25 | 1.47 | 0.74 | 0.69 | 1.12 | 2.15 | 0.68 | 902 | 13.53 |

| 30 | 1.09 | 1.08 | 0.93 | 0.69 | 1.13 | 1.10 | 1.55 | 2.57 | 1.66 | 1312 | 19.68 |

| 31 | 0.69 | 0.49 | 1.16 | 0.39 | 0.92 | 0.65 | 1.13 | 2.68 | 0.63 | 794 | 11.91 |

| 32 | 1.12 | 1.47 | 1.25 | 0.91 | 1.25 | 1.28 | 2.24 | 0.22 | 3.32 | 397 | 5.96 |

| 33 | 0.85 | 1.07 | 1.76 | 0.57 | 1.08 | 1.34 | 2.96 | 1.20 | 1.50 | 1611 | 24.17 |

| 34 | 0.91 | 1.24 | 0.88 | 0.59 | 1.29 | 1.00 | 0.86 | 1.12 | 0.95 | 193 | 3.47 |

| 35 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 1.13 | 0.65 | 0.82 | 0.98 | 2.94 | 8.38 | 1.22 | 1072 | 16.08 |

| 36 | 0.82 | 0.71 | 1.74 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 1.41 | 6.04 | 0.86 | 726 | 10.89 |

| 37 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.68 | 0.82 | 0.91 | 1.45 | 0.60 | 1.15 | 422 | 6.33 |

| 38 | 0.95 | 0.75 | 1.36 | 0.79 | 1.02 | 0.90 | 1.86 | 13.24 | 1.12 | 731 | 10.97 |

| 39 | 0.81 | 0.62 | 1.58 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.90 | 1.06 | 0.96 | 0.84 | 128 | 1.79 |

| 40 | 1.30 | 1.47 | 1.00 | 1.76 | 1.01 | 1.28 | 1.39 | 0.53 | 1.18 | 514 | 7.71 |

| 41 | 0.92 | 0.75 | 0.98 | 1.10 | 0.72 | 1.05 | 1.79 | 1.09 | 0.75 | 67 | 0.94 |

| 42 | 0.71 | 0.59 | 1.23 | 0.82 | 0.98 | 0.87 | 1.49 | 2.45 | 1.06 | 888 | 13.32 |

| 43 | 0.63 | 0.51 | 1.24 | 0.99 | 0.86 | 0.75 | 1.53 | 1.40 | 0.72 | 409 | 1.27 |

| 44 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 1.30 | 0.80 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 1.56 | 8.23 | 1.01 | 509 | 7.64 |

| 45 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 2.00 | 0.87 | 1.22 | 0.96 | 1.08 | 6.27 | 1.18 | 156 | 2.18 |

| 46 | 0.47 | 0.43 | 1.46 | 0.58 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.35 | 9.08 | 0.62 | 146 | 2.04 |

| 47 | 0.68 | 0.43 | 1.41 | 0.54 | 0.70 | 0.92 | 1.56 | 2.75 | 0.42 | 179 | 2.51 |

| 48 | 0.85 | 0.74 | 1.50 | 0.85 | 1.00 | 1.16 | 1.61 | 4.57 | 0.71 | 357 | 5.00 |

| 49 | 1.09 | 1.42 | 1.06 | 1.55 | 1.25 | 1.09 | 1.08 | 0.23 | 1.18 | 263 | 3.95 |

| 50 | 0.69 | 0.48 | 2.18 | 1.07 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 1.03 | 10.17 | 0.59 | 115 | 1.61 |

| 51 | 0.86 | 1.50 | 0.91 | 0.96 | 1.06 | 1.08 | 1.53 | 0.76 | 1.32 | 394 | 5.91 |

| 52 | 0.60 | 0.39 | 1.47 | 0.42 | 0.61 | 0.70 | 1.53 | 0.26 | 0.60 | 378 | 5.67 |

| 53 | 0.73 | 0.65 | 1.24 | 0.60 | 0.95 | 1.06 | 1.61 | 2.55 | 0.89 | 622 | 9.33 |

| 54 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 1.04 | 0.84 | 1.11 | 1.24 | 1.36 | 0.92 | 0.54 | 695 | 10.43 |

| 55 | 1.15 | 0.88 | 2.11 | 1.63 | 1.46 | 1.57 | 1.01 | 1.19 | 1.39 | 134 | 1.88 |

| 56 | 0.69 | 0.56 | 1.26 | 0.55 | 1.02 | 0.86 | 0.72 | 4.96 | 0.67 | 492 | 7.38 |

| 57 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.90 | 0.32 | 0.69 | 0.65 | 0.82 | 2.00 | 0.79 | 117 | 1.64 |

| 58 | 0.99 | 0.89 | 1.74 | 1.04 | 1.48 | 1.51 | 1.81 | 0.38 | 1.42 | 362 | 5.07 |

| 59 | 0.91 | 0.73 | 2.02 | 1.25 | 1.14 | 1.44 | 1.32 | 1.04 | 1.56 | 664 | 9.96 |

| 60 | 0.70 | 1.09 | 1.16 | 1.01 | 1.16 | 0.97 | 1.50 | 1.53 | 1.24 | 253 | 3.80 |

| 61 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 324 | 4.54 |

Appendix A.2

| Patient Number | Average γ-H2AX + 53BP1 Foci/Cell | Dose–Length Product [mGy·cm] | Estimated Effective Dose [mSv] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre- Exposure | Post- Exposure | RIF | |||

| 43 | 0.63 | 0.46 | −0.17 | 409 | 1.27 |

| 44 | 0.49 | 0.59 | 0.10 | 509 | 7.64 |

| 45 | 0.78 | 0.95 | 0.17 | 156 | 2.18 |

| 46 | 0.72 | 0.89 | 0.17 | 146 | 2.04 |

| 47 | 1.21 | 1.35 | 0.14 | 179 | 2.51 |

| 48 | 0.73 | 0.87 | 0.14 | 357 | 5.00 |

| 49 | 0.34 | 0.29 | −0.05 | 263 | 3.95 |

| 50 | 0.28 | 0.58 | 0.30 | 115 | 1.61 |

| 51 | 0.63 | 0.45 | −0.18 | 394 | 5.91 |

| 52 | 0.51 | 0.70 | 0.19 | 378 | 5.67 |

| 53 | 0.36 | 0.52 | 0.16 | 622 | 9.33 |

| 61 | 0.55 | 0.80 | 0.25 | 324 | 4.54 |

Appendix A.3

| Patient Number | Indication for Scan | Anatomic Region of Scan | Conversion Factor (k) | Prior Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Assessment of vascular status | Neck/Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 2 | Staging | Neck/Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | pT1 squamous cell carcinoma |

| 3 | Planning Transcatheter aortic valve replacement | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | Metastatic prostate cancer |

| 4 | Planning Transcatheter aortic valve replacement | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 5 | Fracture rule-out | Thorax | 0.014 | |

| 6 | Left atrial appendage thrombus rule-out | Thorax | 0.014 | |

| 7 | Planning mitral valve replacement | Heart | 0.014 | |

| 8 | Indeterminate pancreatic mass | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 9 | Planning Transcatheter aortic valve replacement | Neck/Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 10 | Assessment of vascular status | Whole Body | 0.015 | |

| 11 | Staging | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | Status post-sigmoid carcinoma (without recurrence) |

| 12 | Planning Transcatheter aortic valve replacement | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | Papillary renal cell carcinoma |

| 13 | Planning Transcatheter aortic valve replacement | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | Prostate cancer |

| 14 | Planning Transcatheter aortic valve replacement | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 15 | Assessment of vascular status | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 16 | Planning Transcatheter aortic valve replacement | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | Status post-adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus |

| 17 | Assessment of vascular status | Neck/Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 18 | Planning Transcatheter aortic valve replacement | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| 19 | Echinococcosis rule-out | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 20 | Assessment of vascular status | Hals/Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 21 | Assessment of vascular status | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | Mycotic aneurysm of the infrarenal aorta |

| 22 | Planning Transcatheter aortic valve replacement | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 23 | Planning organ donation | Abdomen | 0.015 | |

| 24 | Superior mesenteric vein thrombosis follow-up | Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 25 | Abdominal aortic aneurysm | Neck/Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 26 | Aortic Stent follow-up | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 27 | Asthma | Thorax | 0.014 | |

| 28 | Porcelain aorta | Thorax | 0.014 | |

| 29 | Thoracic endovascular aortic repair follow-up | Neck/Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 30 | Recurrent incisional hernia | Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 31 | Planning Transcatheter aortic valve replacement | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 32 | Control spleen drainage | Abdomen | 0.015 | |

| 33 | Follow-up aortic dissection | Neck/Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 34 | Planning Transcatheter aortic valve replacement | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | Status post-breast cancer (27 years ago, no recurrence) |

| 35 | Assessment of vascular status | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 36 | Assessment of vascular status | Neck/Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 37 | Planning Transcatheter aortic valve replacement | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | Status post-prostate cancer (without recurrence) |

| 38 | Abdominal aortic aneurysm | Neck/Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 39 | Left atrial appendage thrombus rule-out | Thorax | 0.014 | |

| 40 | Planning Transcatheter aortic valve replacement | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 41 | Planning Transcatheter aortic valve replacement revision | Thorax | 0.014 | |

| 42 | Assessment of vascular status | Neck/Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 43 | Coronary bypass planning | Head/Neck | 0.0031 | |

| 44 | Planning inguinal hernia repair | Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 45 | Internal carotid artery stenosis | Neck/Thorax | 0.014 | |

| 46 | Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia | Thorax | 0.014 | |

| 47 | Left atrial appendage thrombus rule-out | Thorax | 0.014 | |

| 48 | Aneurysma Aortenbulbus | Thorax | 0.014 | |

| 49 | Planning Transcatheter aortic valve replacement | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 50 | Left atrial appendage thrombus rule-out | Thorax | 0.014 | |

| 51 | Thrombangitis | Thorax/Abdomen | 0.015 | |

| 52 | Planning Transcatheter aortic valve replacement | Neck/Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 53 | Assessment of vascular status | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 54 | Assessment of vascular status | Whole Body | 0.015 | |

| 55 | Left atrial appendage thrombus rule-out | Thorax | 0.014 | |

| 56 | Assessment of vascular status | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 57 | Coronary status and calcium scoring | Heart | 0.014 | |

| 58 | Left atrial appendage thrombus rule-out | Thorax | 0.014 | |

| 59 | Assessment of vascular status | Neck/Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 60 | Planning Transcatheter aortic valve replacement | Thorax/Abdomen/Pelvis | 0.015 | |

| 61 | Left atrial appendage thrombus rule-out | Thorax | 0.014 |

References

- Gray, L.H. Comparative studies of the biological effects of X-rays, neutrons and other ionizing radiations. Br. Med. Bull. 1946, 4, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentin, J. Low-dose extrapolation of radiation-related cancer risk. Ann. ICRP 2005, 35, 1–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, S.; Bowers, J.Z. The acute radiation syndrome in man. Ann. Intern. Med. 1950, 32, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundesamt für Strahlenschutz. Natürliche Strahlung in Deutschland. Available online: https://www.bfs.de/DE/themen/ion/umwelt/natuerliche-strahlung/natuerliche-strahlung_node.html (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Schegerer, A.A.; Nagel, H.-D.; Stamm, G.; Adam, G.; Brix, G. Current CT practice in Germany: Results and implications of a nationwide survey. Eur. J. Radiol. 2017, 90, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.J.; Hardenbergh, P.H.; Constine, L.S.; Lipshultz, S.E. Radiation-associated cardiovascular disease. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2003, 45, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.J.; Lipshultz, S.E.; Schwartz, C.; Fajardo, L.F.; Coen, V.; Constine, L.S. Radiation-associated cardiovascular disease: Manifestations and management. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2003, 13, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauptmann, M.; Daniels, R.D.; Cardis, E.; Cullings, H.M.; Kendall, G.; Laurier, D.; Linet, M.S.; Little, M.P.; Lubin, J.H.; Preston, D.L.; et al. Epidemiological Studies of Low-Dose Ionizing Radiation and Cancer: Summary Bias Assessment and Meta-Analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2020, 2020, 188–200, Erratum in JNCI Monographs, 2023, 2023, e1. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncimonographs/lgac027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannoun, F.; Blettner, M.; Schmidberger, H.; Zeeb, H. Radiation protection in diagnostic radiology. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2008, 105, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, Y.; Yoshida, M.A.; Fujioka, K.; Kurosu, Y.; Ujiie, R.; Yanagi, A.; Tsuyama, N.; Miura, T.; Inaba, T.; Kamiya, K.; et al. Dose-response curves for analyzing of dicentric chromosomes and chromosome translocations following doses of 1000 mGy or less, based on irradiated peripheral blood samples from five healthy individuals. J. Radiat. Res. 2018, 59, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moquet, J.; Sun, M.; Ainsbury, L.; Barnard, S. Doses in Radiation Accidents Investigated by Chromosomal Aberration Analysis, XXVI: Review of Cases Investigated, 2016 to 2023; National Radiological Protection Board: Chilton, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, D.; Abe, Y.; Goh Swee Ting, V.; Nakayama, R.; Takebayashi, K.; Tran Thanh, M.; Fujishima, Y.; Nakata, A.; Ariyoshi, K.; Kasai, K.; et al. Cytogenetic Biodosimetry in Radiation Emergency Medicine: 5. The Dicentric Chromosome and its Role in Biodosimetry. Radiat. Environ. Med. 2023, 12, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Port, M.; Ostheim, P.; Majewski, M.; Voss, T.; Haupt, J.; Lamkowski, A.; Abend, M. Rapid High-Throughput Diagnostic Triage after a Mass Radiation Exposure Event Using Early Gene Expression Changes. Radiat. Res. 2019, 192, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, B.M.; Neumann, D.; Piberger, A.L.; Risnes, S.F.; Koberle, B.; Hartwig, A. Use of high-throughput RT-qPCR to assess modulations of gene expression profiles related to genomic stability and interactions by cadmium. Arch. Toxicol. 2016, 90, 2745–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schüle, S.; Ostheim, P.; Port, M.; Abend, M. Identifying radiation responsive exon-regions of genes often used for biodosimetry and acute radiation syndrome prediction. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobrich, M.; Rief, N.; Kuhne, M.; Heckmann, M.; Fleckenstein, J.; Rube, C.; Uder, M. In vivo formation and repair of DNA double-strand breaks after computed tomography examinations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 8984–8989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberlein, U.; Peper, M.; Fernandez, M.; Lassmann, M.; Scherthan, H. Calibration of the gamma-H2AX DNA double strand break focus assay for internal radiation exposure of blood lymphocytes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, S.; Scherthan, H.; Frank, T.; Lapa, C.; Muller, J.; Seifert, S.; Lassmann, M.; Eberlein, U. DNA Damage in Blood Leukocytes of Prostate Cancer Patients Undergoing PET/CT Examinations with [(68)Ga]Ga-PSMA I&T. Cancers 2020, 12, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüle, S.; Hackenbroch, C.; Beer, M.; Ostheim, P.; Hermann, C.; Muhtadi, R.; Stewart, S.; Port, M.; Scherthan, H.; Abend, M. Tin prefiltration in computed tomography does not significantly alter radiation-induced gene expression and DNA double-strand break formation. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0315808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaatsch, H.L.; Kubitscheck, L.; Wagner, S.; Hantke, T.; Preiss, M.; Ostheim, P.; Nestler, T.; Piechotka, J.; Overhoff, D.; Brockmann, M.A.; et al. Routine CT Diagnostics Cause Dose-Dependent Gene Expression Changes in Peripheral Blood Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassmann, M.; Hanscheid, H.; Gassen, D.; Biko, J.; Meineke, V.; Reiners, C.; Scherthan, H. In vivo formation of gamma-H2AX and 53BP1 DNA repair foci in blood cells after radioiodine therapy of differentiated thyroid cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2010, 51, 1318–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, D.; Guberina, N.; Zensen, S.; Opitz, M.; Forsting, M.; Wetter, A. Radiation Exposure in Computed Tomography. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2023, 120, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüle, S.; Bristy, E.A.; Muhtadi, R.; Kaletka, G.; Stewart, S.; Ostheim, P.; Hermann, C.; Asang, C.; Pleimes, D.; Port, M.; et al. Four Genes Predictive for the Severity of Hematological Damage Reveal a Similar Response after X Irradiation and Chemotherapy. Radiat. Res. 2023, 199, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostheim, P.; Don Mallawaratchy, A.; Muller, T.; Schule, S.; Hermann, C.; Popp, T.; Eder, S.; Combs, S.E.; Port, M.; Abend, M. Acute radiation syndrome-related gene expression in irradiated peripheral blood cell populations. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2021, 97, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baechler, E.C.; Batliwalla, F.M.; Karypis, G.; Gaffney, P.M.; Moser, K.; Ortmann, W.A.; Espe, K.J.; Balasubramanian, S.; Hughes, K.M.; Chan, J.P.; et al. Expression levels for many genes in human peripheral blood cells are highly sensitive to ex vivo incubation. Genes. Immun. 2004, 5, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitsis, R.N.; Leinwand, L.A. Discordance between gene regulation in vitro and in vivo. Gene Expr. 1992, 2, 313–318. [Google Scholar]

- McMullen, P.D.; Pendse, S.N.; Black, M.B.; Mansouri, K.; Haider, S.; Andersen, M.E.; Clewell, R.A. Addressing systematic inconsistencies between in vitro and in vivo transcriptomic mode of action signatures. Toxicol. In Vitro 2019, 58, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.G.; Grom, A.A.; Griffin, T.A.; Colbert, R.A.; Thompson, S.D. Gene Expression Profiles from Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells Are Sensitive to Short Processing Delays. Biopreserv Biobank 2010, 8, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaatsch, H.L.; Becker, B.V.; Schule, S.; Ostheim, P.; Nestler, K.; Jakobi, J.; Schafer, B.; Hantke, T.; Brockmann, M.A.; Abend, M.; et al. Gene expression changes and DNA damage after ex vivo exposure of peripheral blood cells to various CT photon spectra. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, G.; Sarusi-Portuguez, A.; Loza, O.; Shimoni-Sebag, A.; Yoron, O.; Lawrence, Y.R.; Zach, L.; Hakim, O. Dose-Dependent Transcriptional Response to Ionizing Radiation Is Orchestrated with DNA Repair within the Nuclear Space. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.-H.; Zhao, Z.-Q.; He, X.-P.; Wang, H.-P.; Xu, Q.-Z.; An, J.; Bai, B.; Sui, J.-L.; Zhou, P.-K. Dose-dependent expression changes of early response genes to ionizing radiation in human lymphoblastoid cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2007, 19, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beels, L.; Bacher, K.; Smeets, P.; Verstraete, K.; Vral, A.; Thierens, H. Dose-length product of scanners correlates with DNA damage in patients undergoing contrast CT. Eur. J. Radiol. 2012, 81, 1495–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüle, S.; Hackenbroch, C.; Beer, M.; Muhtadi, R.; Hermann, C.; Stewart, S.; Schwanke, D.; Ostheim, P.; Port, M.; Scherthan, H.; et al. Ex-vivo dose response characterization of the recently identified EDA2R gene after low level radiation exposures and comparison with FDXR gene expression and the gammaH2AX focus assay. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2023, 99, 1584–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.A.; Andrysik, Z.; Dengler, V.L.; Mellert, H.S.; Guarnieri, A.; Freeman, J.A.; Sullivan, K.D.; Galbraith, M.D.; Luo, X.; Kraus, W.L.; et al. Global analysis of p53-regulated transcription identifies its direct targets and unexpected regulatory mechanisms. eLife 2014, 3, e02200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeay, S.; Gaulis, S.; Ferretti, S.; Bitter, H.; Ito, M.; Valat, T.; Murakami, M.; Ruetz, S.; Guthy, D.A.; Rynn, C.; et al. A distinct p53 target gene set predicts for response to the selective p53-HDM2 inhibitor NVP-CGM097. eLife 2015, 4, e06498, Erratum in Elife, 2016, 5, e19317. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.19317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.; Schilling, D.; Dobiasch, S.; Raulefs, S.; Santiago Franco, M.; Buschmann, D.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Schmid, T.E.; Combs, S.E. The Emerging Role of miRNAs for the Radiation Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taliaferro, L.P.; Agarwal, R.K.; Coleman, C.N.; DiCarlo, A.L.; Hofmeyer, K.A.; Loelius, S.G.; Molinar-Inglis, O.; Tedesco, D.C.; Satyamitra, M.M. Sex differences in radiation research. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2024, 100, 466–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothkamm, K.; Lobrich, M. Evidence for a lack of DNA double-strand break repair in human cells exposed to very low x-ray doses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 5057–5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothkamm, K.; Balroop, S.; Shekhdar, J.; Fernie, P.; Goh, V. Leukocyte DNA damage after multi-detector row CT: A quantitative biomarker of low-level radiation exposure. Radiology 2007, 242, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Jeggo, P.A.; West, C.; Gomolka, M.; Quintens, R.; Badie, C.; Laurent, O.; Aerts, A.; Anastasov, N.; Azimzadeh, O.; et al. Ionizing radiation biomarkers in epidemiological studies—An update. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2017, 771, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakane, H.; Ishida, M.; Shi, L.; Fukumoto, W.; Sakai, C.; Miyata, Y.; Ishida, T.; Akita, T.; Okada, M.; Awai, K.; et al. Biological Effects of Low-Dose Chest CT on Chromosomal DNA. Radiology 2020, 295, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, S.; Barnard, S.; Rothkamm, K. Gamma-H2AX-based dose estimation for whole and partial body radiation exposure. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamkowski, A.; Forcheron, F.; Agay, D.; Ahmed, E.A.; Drouet, M.; Meineke, V.; Scherthan, H. DNA damage focus analysis in blood samples of minipigs reveals acute partial body irradiation. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfat, M.; Haq, A.; Beg, T.; Jaleel, G. Optimization of CT radiation dose: Insight into DLP and CTDI. Future Health 2024, 2, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCollough, C.; Cody, D.; Edyvean, S.; Geise, R.; Gould, B.; Keat, N.; Huda, W.; Judy, P.; Kalender, W.; McNitt-Gray, M.; et al. Report No. 096—The Measurement, Reporting, and Management of Radiation Dose in CT (2008); American Association of Physicists in Medicine: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- DIN EN ISO 9001/2008; Qualitätsmanagementsysteme–Anforderungen. Beuth-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2008.

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherthan, H.; Geiger, B.; Ridinger, D.; Muller, J.; Riccobono, D.; Bestvater, F.; Port, M.; Hausmann, M. Nano-Architecture of Persistent Focal DNA Damage Regions in the Minipig Epidermis Weeks after Acute gamma-Irradiation. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | N (%) | Mean ± SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | 60 (100%) | 65.2 ± 14.4 | 28.0 | 91.0 | |

| Gender | Male | 39 (65%) | |||

| Female | 21 (35%) | ||||

| DLP [mGy·cm] | All patients | 60 (100%) | 561.9 ± 384.6 | 67.0 | 1725.0 |

| γ-H2AX group | 12 (20%) | 321.0 ± 149.3 | 115.0 | 622.0 | |

| Effective dose estimate [mSv] | All patients | 60 (100%) | 8.3 ± 5.8 | 0.9 | 24.2 |

| γ-H2AX group | 12 (20%) | 4.3 ± 2.4 | 1.3 | 9.3 | |

| Gene of Interest | Incubation | Gender | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Vivo n = 27 | Ex Vivo n = 33 | Male n = 39 | Female n = 21 | |||

| Median | Median | p-Value | Median | Median | p-Value | |

| DGE Relative to Unexposed | ||||||

| DDB2 | 1.09 | 0.73 | <0.001 | |||

| 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.70 | ||||

| FDXR | 1.24 | 0.63 | <0.001 | |||

| 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.75 | ||||

| POU2AF1 | 1.06 | 1.44 | <0.001 | |||

| 1.25 | 1.34 | 0.93 | ||||

| WNT3 | 0.96 | 0.80 | 0.089 | |||

| 0.91 | 0.60 | 0.02 | ||||

| BAX | 1.06 | 0.95 | 0.029 | |||

| 1.02 | 0.96 | 0.28 | ||||

| AEN | 1.17 | 0.90 | <0.001 | |||

| 1.07 | 0.99 | 0.65 | ||||

| EDA2R | 1.57 | 1.41 | 0.019 | |||

| 1.5 | 1.53 | 0.81 | ||||

| MIR34AHG | 1.36 | 2.56 | 0.018 | |||

| 1.89 | 2.00 | 0.88 | ||||

| PHLDA3 | 1.29 | 0.89 | <0.001 | |||

| 1.18 | 0.95 | 0.22 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schmid, N.; Gorte, V.; Akers, M.; Verloh, N.; Haimerl, M.; Stroszczynski, C.; Scherthan, H.; Orben, T.; Stewart, S.; Kubitscheck, L.; et al. Impact of Low-Dose CT Radiation on Gene Expression and DNA Integrity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11869. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411869

Schmid N, Gorte V, Akers M, Verloh N, Haimerl M, Stroszczynski C, Scherthan H, Orben T, Stewart S, Kubitscheck L, et al. Impact of Low-Dose CT Radiation on Gene Expression and DNA Integrity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11869. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411869

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchmid, Nikolai, Vadim Gorte, Michael Akers, Niklas Verloh, Michael Haimerl, Christian Stroszczynski, Harry Scherthan, Timo Orben, Samantha Stewart, Laura Kubitscheck, and et al. 2025. "Impact of Low-Dose CT Radiation on Gene Expression and DNA Integrity" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11869. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411869

APA StyleSchmid, N., Gorte, V., Akers, M., Verloh, N., Haimerl, M., Stroszczynski, C., Scherthan, H., Orben, T., Stewart, S., Kubitscheck, L., Kaatsch, H. L., Port, M., Abend, M., & Ostheim, P. (2025). Impact of Low-Dose CT Radiation on Gene Expression and DNA Integrity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11869. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411869