Potential Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Gintonin-Enriched Fraction in TNF-α-Stimulated Keratinocytes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Effect of GEF and TNF-α on Cell Viability of HaCaT Cells

2.2. Effect of GEF on TNF-α-Induced ROS Production in HaCaT Cells

2.3. Effect of GEF on TNF-α-Induced NO Release in HaCaT Cells

2.4. Effect of GEF on TNF-α-Induced Cytokine Release in HaCaT Cells

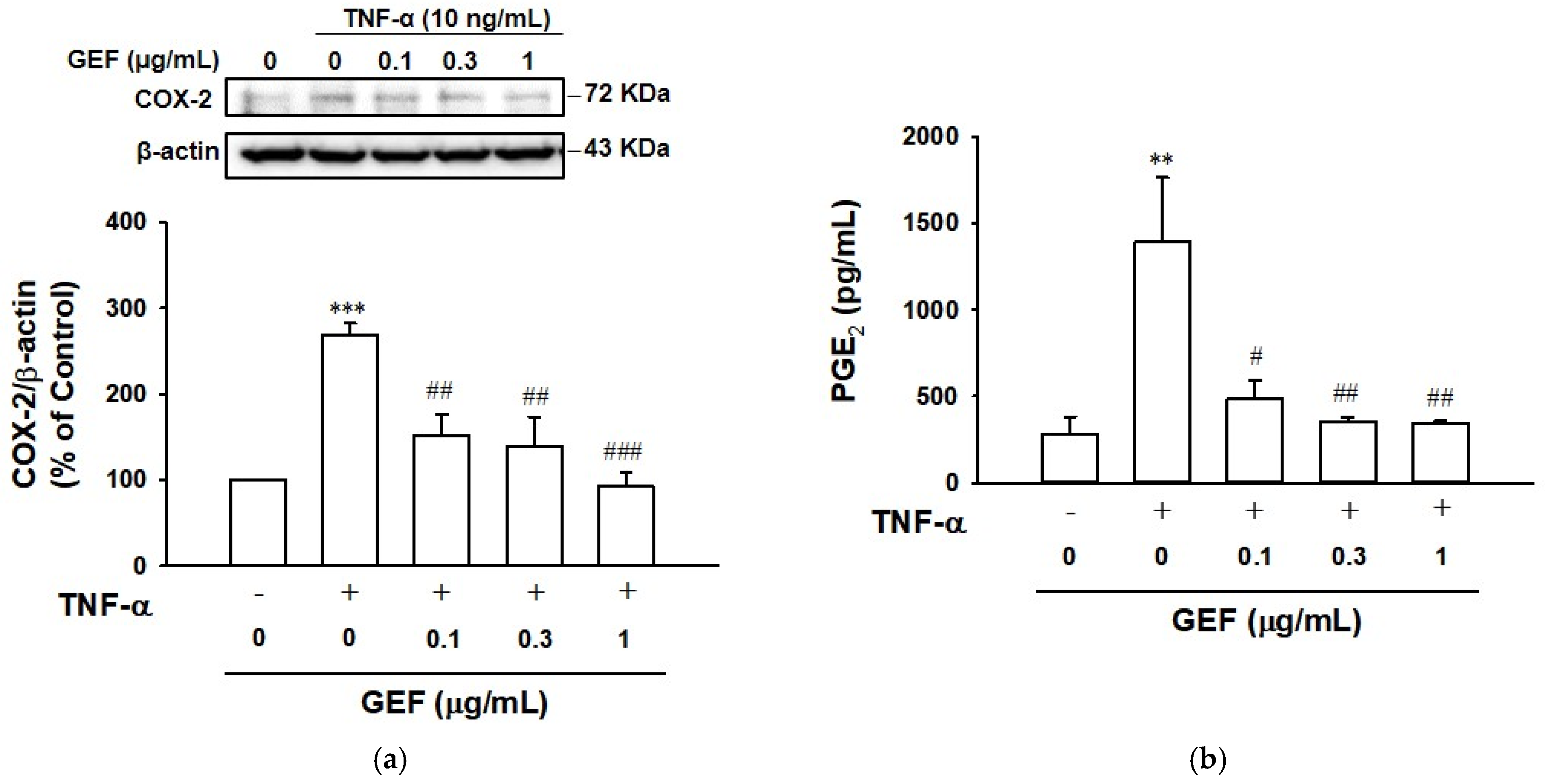

2.5. Effect of GEF on TNF-α-Induced COX-2 and Prostaglandin E2 Expression in HaCaT Cells

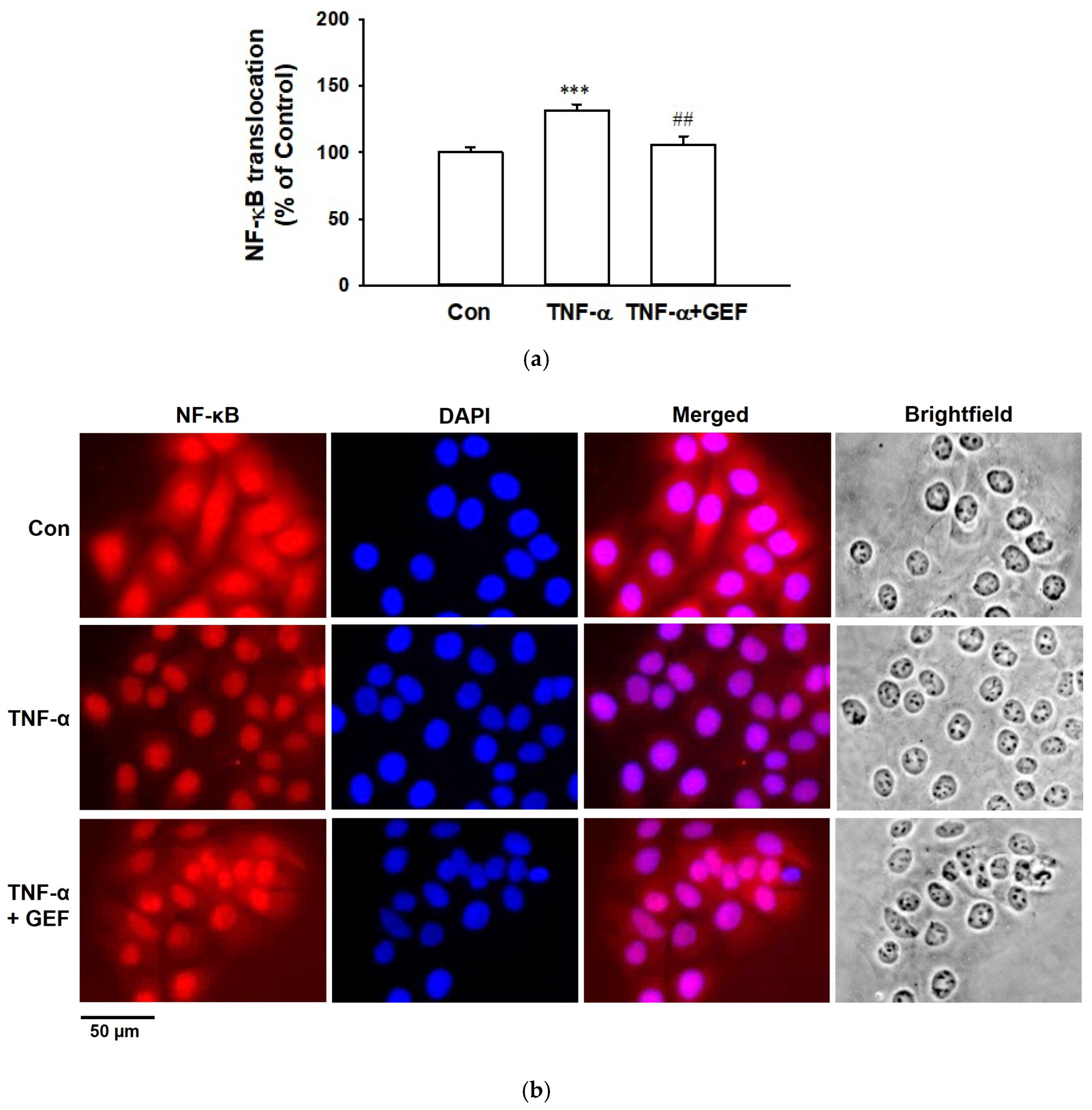

2.6. Effect of GEF on TNF-α-Induced Translocation of NF-κB in HaCaT Cells

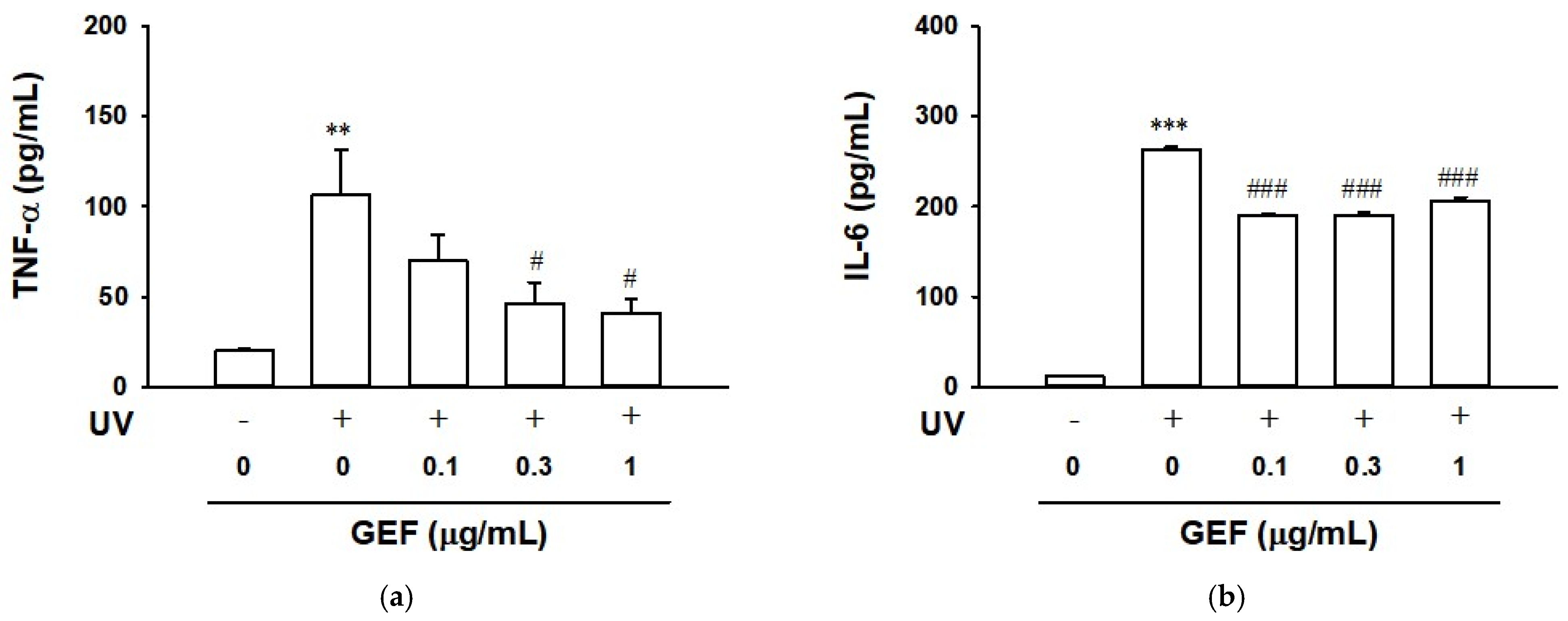

2.7. Effect of GEF on Cytokine Release in Ultraviolet-Irradiated HaCaT Cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Cell Culture

4.3. Cell Viability Assay

4.4. ROS Production Assay

4.5. NO Production Assay

4.6. Cytokine and PGE2 Analysis

4.7. Immunoblotting

4.8. Immunostaining

4.9. UV Irradiation

4.10. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NO | nitric oxide |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor-κB |

| iNOS | inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| IL-6 | interleukin-6 |

| IL-8 | interleukin-8 |

| IL-10 | interleukin-10 |

| RANTES | regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted |

| CCL5 | chemokine (c-c motif) ligand 5 |

| GEF | gintonin-enriched fraction |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-α |

| UVB | ultraviolet B |

References

- Kaur, B.; Singh, P. Inflammation: Biochemistry, cellular targets, anti-inflammatory agents and challenges with special emphasis on cyclooxygenase-2. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 121, 105663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 2017, 9, 7204–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, C.L.R.; Wilairatana, P.; Silva, L.R.; Moreira, P.S.; Vilar Barbosa, N.M.M.; da Silva, P.R.; Coutinho, H.D.M.; de Menezes, I.R.A.; Felipe, C.F.B. Biochemical aspects of the inflammatory process: A narrative review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 168, 115764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shutova, M.S.; Boehncke, W.H. Mechanotransduction in skin inflammation. Cells 2022, 11, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Sun, M.; Zhao, C.; Kang, J. TRPV1: A promising therapeutic target for skin aging and inflammatory skin diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1037925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dec, M.; Arasiewicz, H. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor role in chronic inflammatory skin diseases: A narrative review. Adv. Dermatol. Allergol. 2024, 41, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Lai, Y. Keratinocytes: New perspectives in inflammatory skin diseases. Trends Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, Y.; Cui, L.; Shi, Y.; Guo, C. Advances in the pathogenesis of psoriasis: From keratinocyte perspective. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merecz-Sadowska, A.; Sitarek, P.; Zajdel, K.; Kucharska, E.; Kowalczyk, T.; Zajdel, R. The modulatory influence of plant-derived compounds on human keratinocyte function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corsini, E.; Galbiati, V.; Nikitovic, D.; Tsatsakis, A.M. Role of oxidative stress in chemical allergens induced skin cells activation. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 61, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, C.N.; Koepke, J.I.; Terlecky, L.J.; Borkin, M.S.; Boyd, S.L.; Terlecky, S.R. Reactive oxygen species in tumor necrosis factor-alpha-activated primary human keratinocytes: Implications for psoriasis and inflammatory skin disease. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2008, 128, 2606–2614, Erratum in J. Investig. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 1838. Boyd, Savoy L [corrected to Boyd Savoy, L]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, T.; Gallucci, R.M.; Simeonova, P.P.; Luster, M.I. Regulation and role of interleukin 6 in wounded human epithelial keratinocytes. Cytokine 2001, 15, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.M.; Sharma, M.R.; Werth, V.P. TNF-alpha production in the skin. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2009, 301, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuoka, M.; Ogino, Y.; Sato, H.; Ohta, T.; Komoriya, K.; Nishioka, K.; Katayama, I. RANTES expression in psoriatic skin, and regulation of RANTES and IL-8 production in cultured epidermal keratinocytes by active vitamin D3 (tacalcitol). Br. J. Dermatol. 1998, 138, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.C.; Liao, P.Y.; Hung, S.J.; Ge, J.S.; Chen, S.M.; Lai, J.C.; Hsiao, Y.P.; Yang, J.H. Topical application of glycolic acid suppresses the UVB induced IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1 and COX-2 inflammation by modulating NF-κB signaling pathway in keratinocytes and mice skin. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2017, 86, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Förstermann, U.; Sessa, W.C. Nitric oxide synthases: Regulation and function. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.M. Molecular mechanisms regulating iNOS expression in various cell types. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B 2000, 3, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlini, V.; Noonan, D.M.; Abdalalem, E.; Goletti, D.; Sansone, C.; Calabrone, L.; Albini, A. The multifaceted nature of IL-10: Regulation, role in immunological homeostasis and its relevance to cancer, COVID-19 and post-COVID conditions. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1161067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Peng, X.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Q.; Ding, L.; Li, G.; Qiu, F. Potential of natural products in inflammation: Biological activities, structure-activity relationships, and mechanistic targets. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2024, 47, 377–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, A.; Rodrigues, P.M.; Pintado, M.; Tavaria, F.K. A systematic review of natural products for skin applications: Targeting inflammation, wound healing, and photo-aging. Phytomedicine 2023, 115, 154824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; Cho, H.S.; Kim, J.H.; Cho, H.J.; Choi, S.H.; Hwang, S.H.; Rhim, H.; Cho, I.H.; Rhee, M.H.; Kim, D.G.; et al. A novel protocol for batch-separating gintonin-enriched, polysaccharide-enriched, and crude ginsenoside-containing fractions from Panax ginseng. J. Ginseng Res. 2023, 47, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.J.; Choi, S.H.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, B.H.; Rhim, H.; Kim, H.C.; Hwang, S.H.; Nah, S.Y. Bioactive lipids in gintonin-enriched fraction from ginseng. J. Ginseng Res. 2019, 43, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, W.W.; Kim, M.; Nah, S.Y. Cognitive function improvement effects of gintonin-enriched fraction in subjective memory impairment: An assessor- and participant-blinded placebo-controlled study. J. Ginseng Res. 2023, 47, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Park, G.S.; Lee, R.; Hong, S.; Han, S.; Lee, Y.M.; Nah, S.Y.; Han, S.G.; Oh, J.W. Gintonin-enriched panax ginseng extract induces apoptosis in human melanoma cells by causing cell cycle arrest and activating caspases. Foods 2025, 14, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chei, S.; Song, J.H.; Oh, H.J.; Lee, K.; Jin, H.; Choi, S.H.; Nah, S.Y.; Lee, B.Y. Gintonin-enriched fraction suppresses heat stress-induced inflammation through LPA receptor. Molecules 2020, 25, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Lau, S.S.; Monks, T.J. The cytoprotective effect of N-acetyl-L-cysteine against ROS-induced cytotoxicity is independent of its ability to enhance glutathione synthesis. Toxicol. Sci. 2011, 120, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetrick, E.M.; Schoenfisch, M.H. Analytical chemistry of nitric oxide. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2009, 2, 409–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun, K.S.; Langenbach, R. A proposed COX-2 and PGE(2) receptor interaction in UV-exposed mouse skin. Mol. Carcinog. 2007, 46, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, M.S.; Ghosh, S. Regulation of NF-κB by TNF family cytokines. Semin. Immunol. 2014, 26, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshizumi, M.; Nakamura, T.; Kato, M.; Ishioka, T.; Kozawa, K.; Wakamatsu, K.; Kimura, H. Release of cytokines/chemokines and cell death in UVB-irradiated human keratinocytes, HaCaT. Cell Biol. Int. 2008, 32, 1405–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, E.; Jeon, B.R.; Jeong, D.H.; Lee, K.; Goo, Y.K.; Kwak, D.; Kim, S.; Roh, S.S.; Kim, S.D.; Nah, S.Y.; et al. A novel Korean red ginseng compound gintonin inhibited inflammation by MAPK and NF-κB pathways and recovered the levels of mir-34a and mir-93 in RAW 264.7 cells. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 624132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Won, K.J.; Lee, R.; Cho, H.S.; Hwang, S.H.; Nah, S.Y. Wound healing effect of gintonin involves lysophosphatidic acid receptor/vascular endothelial growth factor signaling pathway in keratinocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, K.J.; Lee, R.; Choi, S.H.; Kim, J.H.; Hwang, S.H.; Nah, S.Y. Gintonin-induced wound-healing-related responses involve epidermal-growth-factor-like effects in keratinocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Zhou, H.; Wang, X.; Yu, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, P.; Zhao, F.; Zeng, F.; Li, G.; Li, Y.; et al. Atopic dermatitis: Pathogenesis and therapeutic intervention. MedComm 2024, 5, e70029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Novak, N. Pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2015, 45, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pocino, K.; Carnazzo, V.; Stefanile, A.; Basile, V.; Guerriero, C.; Marino, M.; Rigante, D.; Basile, U. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha: Ally and enemy in protean cutaneous sceneries. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.; Kolb, N.; Werner, E.R.; Pfeilschifter, J. Coordinated induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase and GTP-cyclohydrolase I is dependent on inflammatory cytokines and interferon-gamma in HaCaT keratinocytes: Implications for the model of cutaneous wound repair. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1998, 111, 1065–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirsjö, A.; Karlsson, M.; Gidlöf, A.; Rollman, O.; Törmä, H. Increased expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in psoriatic skin and cytokine-stimulated cultured keratinocytes. Br. J. Dermatol. 1996, 134, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallucci, R.M.; Sloan, D.K.; Heck, J.M.; Murray, A.R.; O’Dell, S.J. Interleukin 6 indirectly induces keratinocyte migration. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2004, 122, 764–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Quintero, M.; Kuri-Harcuch, W.; González Robles, A.; Castro-Muñozledo, F. Interleukin-6 promotes human epidermal keratinocyte proliferation and keratin cytoskeleton reorganization in culture. Cell Tissue Res. 2006, 325, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, B.Z.; Stevenson, A.W.; Prêle, C.M.; Fear, M.W.; Wood, F.M. The role of IL-6 in skin fibrosis and cutaneous wound healing. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossman, R.M.; Krueger, J.; Yourish, D.; Granelli-Piperno, A.; Murphy, D.P.; May, L.T.; Kupper, T.S.; Sehgal, P.B.; Gottlieb, A.B. Interleukin 6 is expressed in high levels in psoriatic skin and stimulates proliferation of cultured human keratinocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 6367–6371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirnbauer, R.; Köck, A.; Neuner, P.; Förster, E.; Krutmann, J.; Urbanski, A.; Schauer, E.; Ansel, J.C.; Schwarz, T.; Luger, T.A. Regulation of epidermal cell interleukin-6 production by UV light and corticosteroids. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1991, 96, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsushima, K.; Yang, D.; Oppenheim, J.J. Interleukin-8: An evolving chemokine. Cytokine 2022, 153, 155828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewe, M.; Gyufko, K.; Krutmann, J. Interleukin-10 production by cultured human keratinocytes: Regulation by ultraviolet B and ultraviolet A1 radiation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1995, 104, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byun, J.Y.; Choi, H.Y.; Myung, K.B.; Choi, Y.W. Expression of IL-10, TGF-beta(1) and TNF-alpha in cultured keratinocytes (HaCaT cells) after IPL treatment or ALA-IPL photodynamic treatment. Ann. Dermatol. 2009, 21, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, M.; Sabat, R.; Krätzschmar, J.; Seidel, H.; Wolk, K.; Schönbein, C.; Schütt, S.; Friedrich, M.; Döcke, W.D.; Asadullah, K.; et al. Expression profiling of IL-10-regulated genes in human monocytes and peripheral blood mononuclear cells from psoriatic patients during IL-10 therapy. Eur. J. Immunol. 2004, 34, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadullah, K.; Sabat, R.; Friedrich, M.; Volk, H.D.; Sterry, W. Interleukin-10: An important immunoregulatory cytokine with major impact on psoriasis. Curr. Drug Targets Inflamm. Allergy 2004, 3, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaussikaa, S.; Prasad, M.K.; Ramkumar, K.M. Nrf2 activation in keratinocytes: A central role in diabetes-associated wound healing. Exp. Dermatol. 2024, 33, e15189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, M.; Choi, J.H.; Chang, Y.; Lee, S.J.; Nah, S.Y.; Cho, I.H. Gintonin, a ginseng-derived ingredient, as a novel therapeutic strategy for Huntington’s disease: Activation of the Nrf2 pathway through lysophosphatidic acid receptors. Brain Behav. Immun. 2019, 80, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, H.; Zhao, X.; Sun, S.C. NF-κB in inflammation and cancer. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2025, 22, 811–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, R.G.; Hayden, M.S.; Ghosh, S. NF-κB, inflammation, and metabolic disease. Cell Metab. 2011, 13, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldminz, A.M.; Au, S.C.; Kim, N.; Gottlieb, A.B.; Lizzul, P.F. NF-κB: An essential transcription factor in psoriasis. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2013, 69, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetsuka, T.; Daphna-Iken, D.; Srivastava, S.K.; Baier, L.D.; DuMaine, J.; Morrison, A.R. Cross-talk between cyclooxygenase and nitric oxide pathways: Prostaglandin E2 negatively modulates induction of nitric oxide synthase by interleukin 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 12168–12172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patruno, A.; Amerio, P.; Pesce, M.; Vianale, G.; Di Luzio, S.; Tulli, A.; Franceschelli, S.; Grilli, A.; Muraro, R.; Reale, M. Extremely low frequency electromagnetic fields modulate expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase, endothelial nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 in the human keratinocyte cell line HaCat: Potential therapeutic effects in wound healing. Br. J. Dermatol. 2010, 162, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si-Si, W.; Liao, L.; Ling, Z.; Yun-Xia, Y. Inhibition of TNF-α/IFN-γ induced RANTES expression in HaCaT cell by naringin. Pharm. Biol. 2011, 49, 810–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhu, L.; Feng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, L.; Ran, Y. Effects of acitretin on proliferative inhibition and RANTES production of HaCaT cells. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2008, 300, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, R.; Won, K.-J.; Kim, J.-H.; Choi, S.-H.; Hwang, S.-H.; Nah, S.-Y. Potential Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Gintonin-Enriched Fraction in TNF-α-Stimulated Keratinocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11864. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411864

Lee R, Won K-J, Kim J-H, Choi S-H, Hwang S-H, Nah S-Y. Potential Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Gintonin-Enriched Fraction in TNF-α-Stimulated Keratinocytes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11864. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411864

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Rami, Kyung-Jong Won, Ji-Hun Kim, Sun-Hye Choi, Sung-Hee Hwang, and Seung-Yeol Nah. 2025. "Potential Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Gintonin-Enriched Fraction in TNF-α-Stimulated Keratinocytes" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11864. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411864

APA StyleLee, R., Won, K.-J., Kim, J.-H., Choi, S.-H., Hwang, S.-H., & Nah, S.-Y. (2025). Potential Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Gintonin-Enriched Fraction in TNF-α-Stimulated Keratinocytes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11864. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411864