Gene Mapping and Genetic Analysis of Maize Resistance to Stalk Rot

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Infection of Maize by F. graminearum

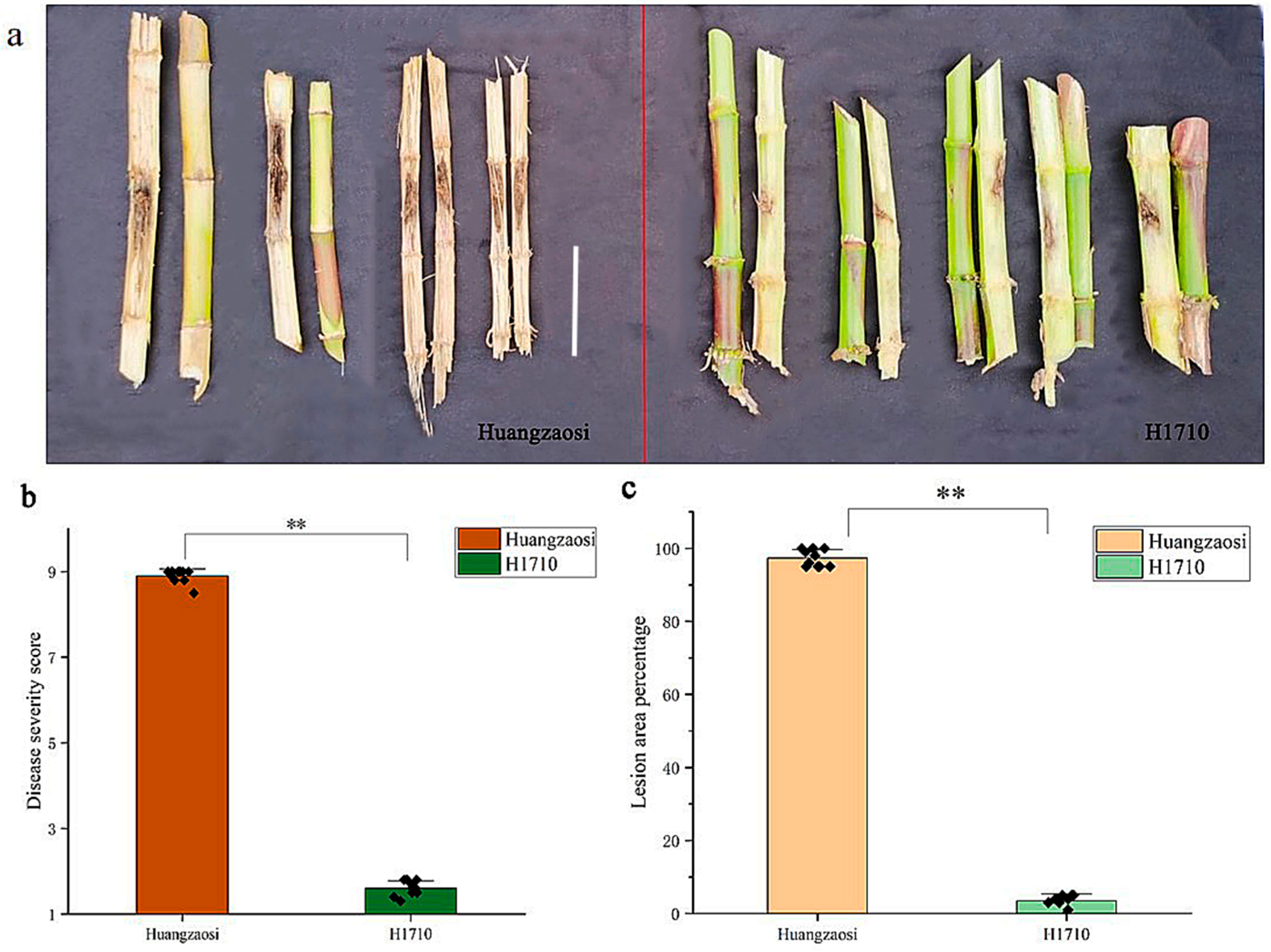

2.2. Phenotypic Identification of Maize Stalk Rot Resistance

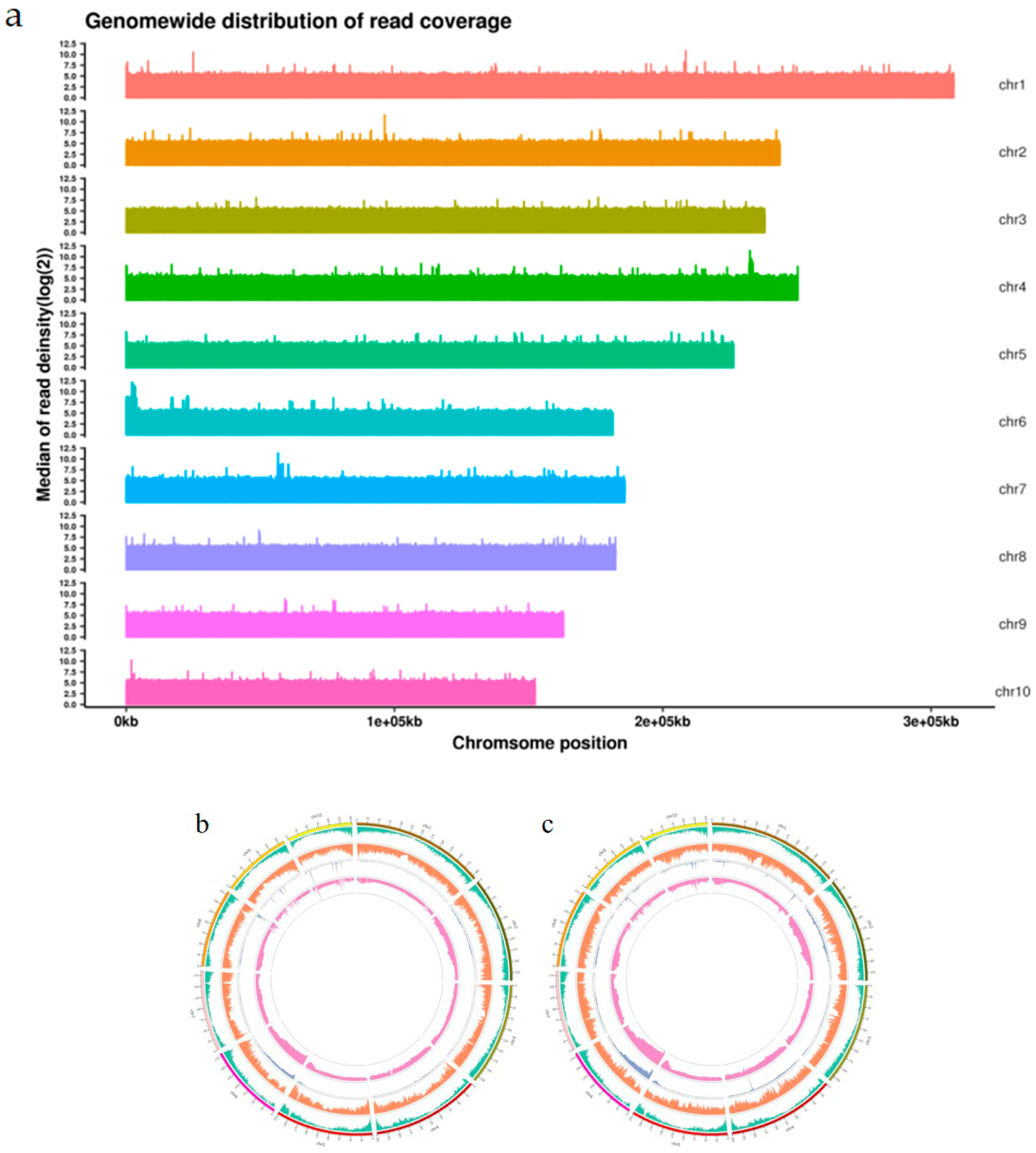

2.3. BSA-Seq Data Analysis

2.3.1. Identification of QTLs Related to Stalk Rot Resistance via BSA-Seq

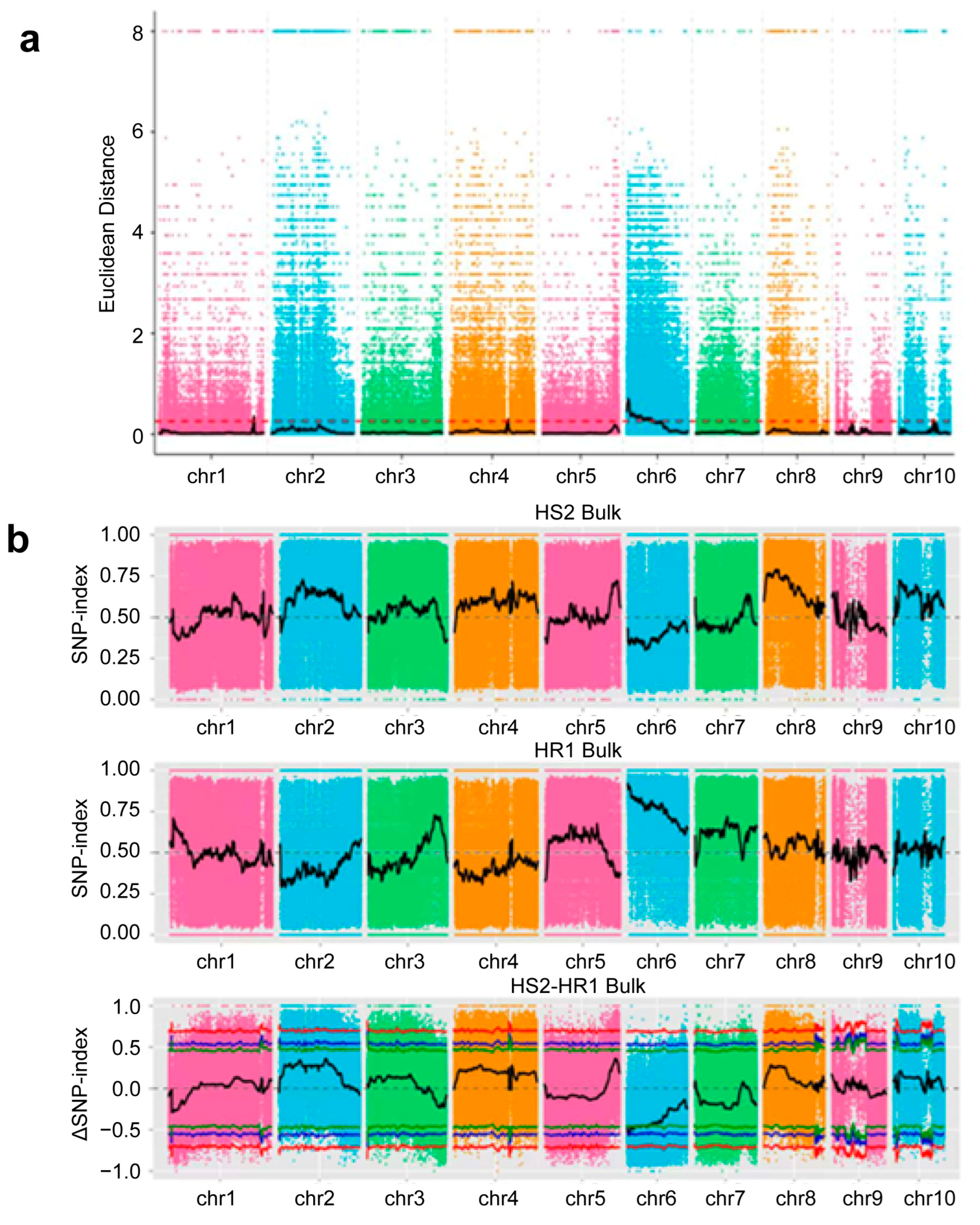

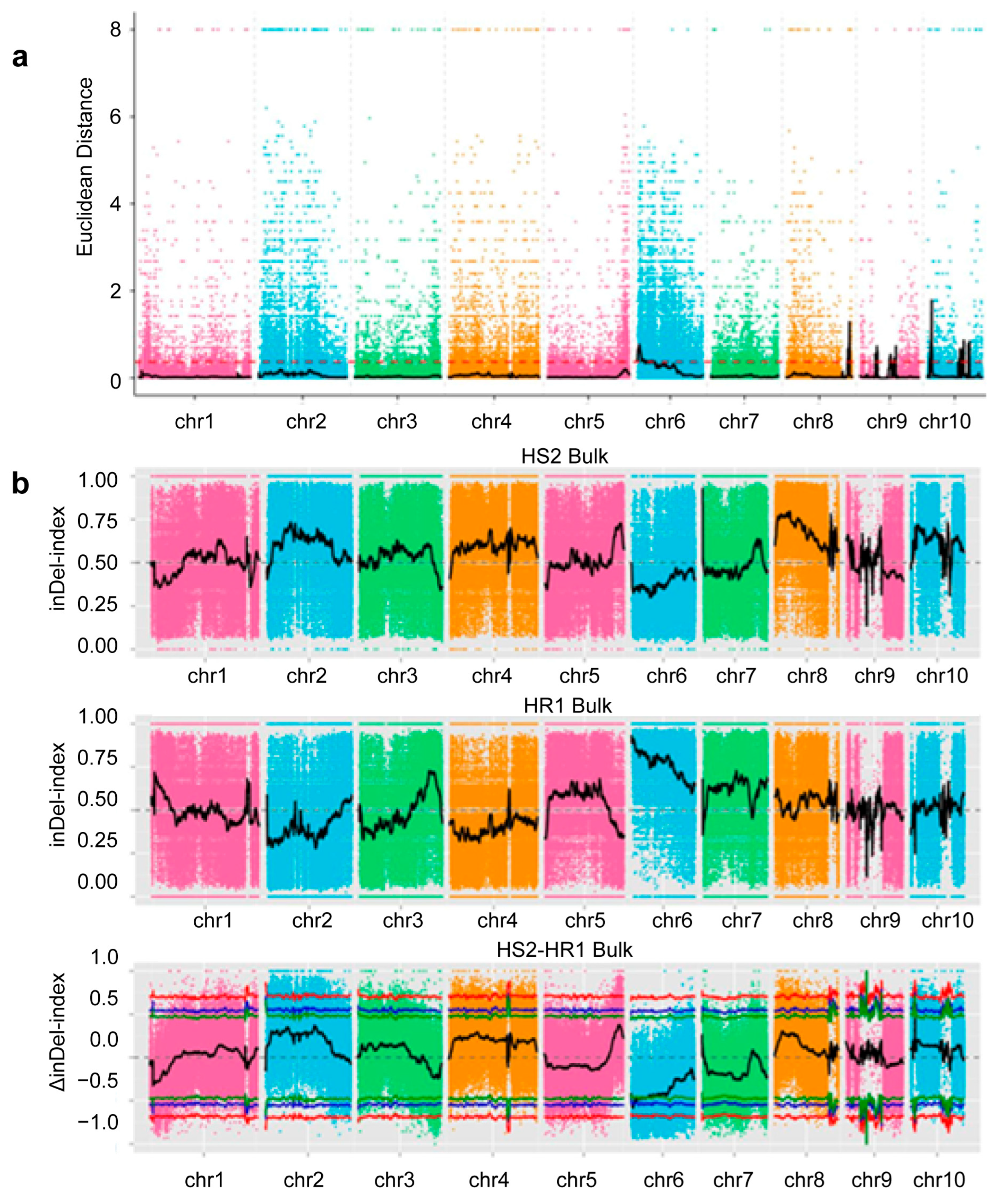

2.3.2. Association Analyses Using the ED Association Algorithm and Index Association Algorithm

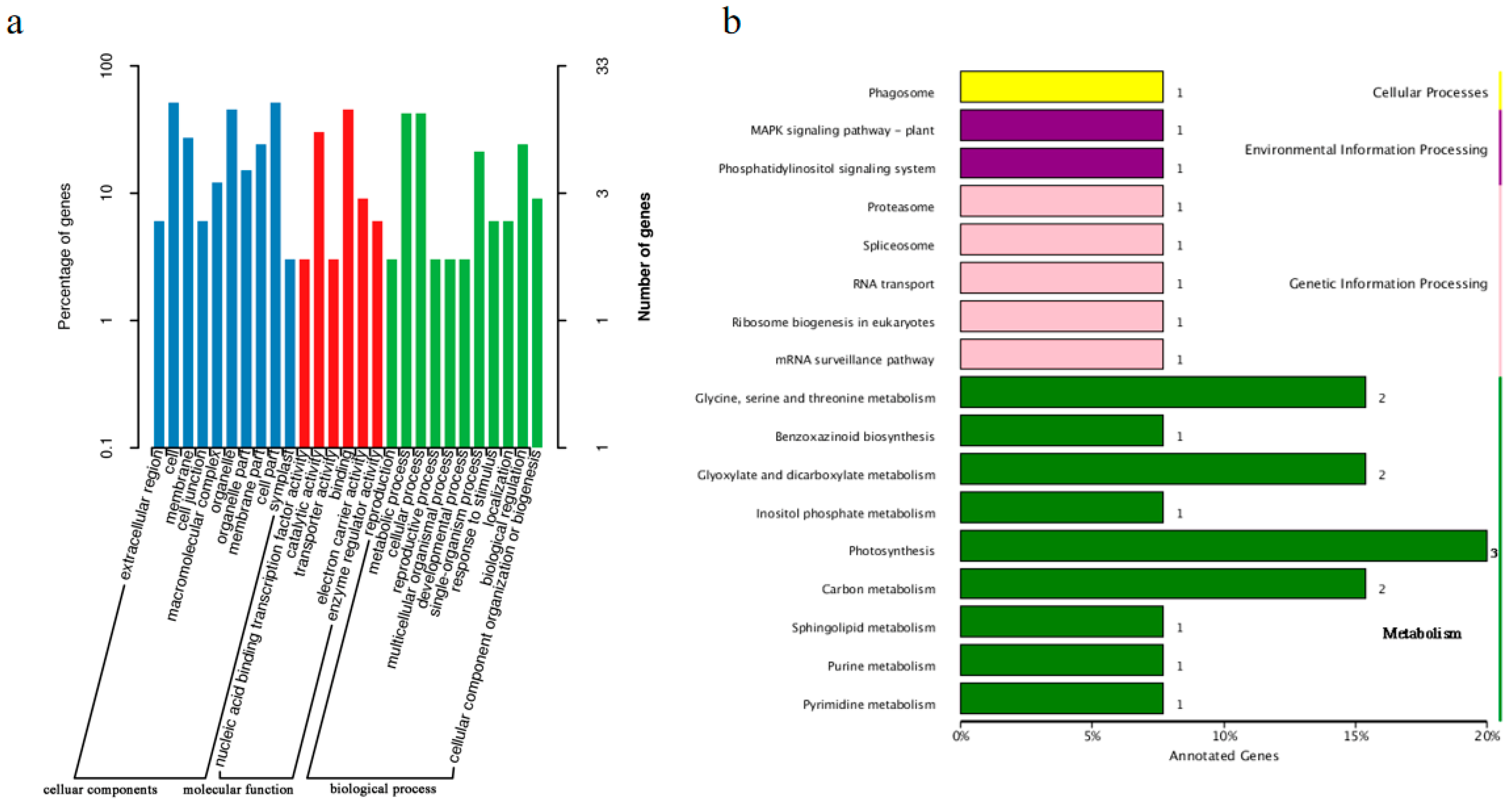

2.4. Annotation of Genes in the Candidate Region

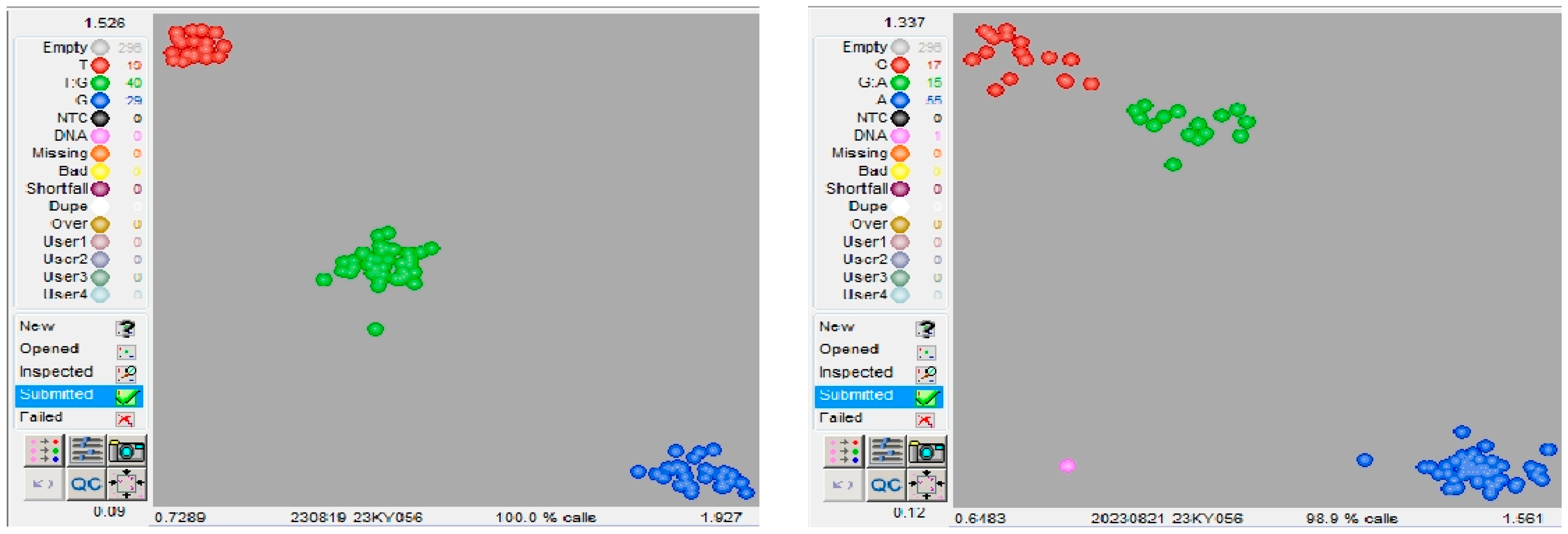

2.5. Competitive Allele-Specific PCR Assay

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Strains and Plant Materials

4.2. Field Resistance Evaluation

4.3. BSA-Seq Analysis

4.4. Candidate Region Gene Annotation

4.5. KASP Marker Development

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. World Food and Agriculture-Statistical Yearbook 2024; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; Volume 2, pp. 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.M.; Wu, Q.A.; Liu, X.J.; Ma, G.Z. Identification and pathogenicity of Pythium spp. isolated from maize. Acta. Phytopathol. Sin. 1994, 4, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.H.; Li, S.; Wu, W.Q.; Sun, S.L.; Zhu, Z.D.; Duan, C.X. Research progress on eesistance of maize to Fusarium and Pythium stalk rot diseases. J. Plant Genet. Resour. 2025, 26, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.H.; Han, J.H.; Lee, J.K.; Kim, K.S. Characterization of the maize stalk rot pathogens Fusarium subglutinans and F. temperatum and the effect of fungicides on their mycelial growth and colony formation. Plant Pathol. J. 2014, 30, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.J.; He, P.; Jin, J.Y. Effect of potassium on ultrastructure of maize stalk pith and young root and their relation to stalk rot resistance. Agric. Sci. China 2010, 9, 1467–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, D.S.; Wise, K.A.; Sisson, A.J.; Allen, T.W.; Bergstrom, G.C.; Bissonnette, K.M.; Wiebold, W.J. Corn yield loss estimates due to diseases in the United States and Ontario, Canada, from 2016 to 2019. Plant Health Progress 2020, 21, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Gao, S.; Hou, L.; Li, L.; Ming, B.; Xie, R.; Li, S. Physiological influence of stalk rot on maize lodging after physiological maturity. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Balint-Kurti, P.; Xu, M.L. Quantitative disease resistance: Dissection and adoption in maize. Mol. Plant. 2017, 10, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Song, J.; Du, W.P.; Xu, L.Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xiang, X.L.; Yu, G.R. Identification, mapping, and molecular marker development for Rgsr8.1: A new quantitative trait locus conferring resistance to Gibberella stalk rot in maize (Zea mays L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.S.; Fu, J.X.; Shang, Z.G.; Song, X.Y.; Zhao, M.M. Combination of genome-wide association study and QTL mapping reveals the genetic architecture of Fusarium stalk rot in maize. Front. Agron. 2021, 2, 590374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Ma, P.; Gao, J.; Dong, C.; Wang, Z.; Luan, Y.; Chen, J.; Sun, D.; Jing, P.; Zhang, X.; et al. Natural variation in maize gene ZmSBR1 confers seedling resistance to Fusarium verticillioides. Crop J. 2024, 12, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, W.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Jia, X.; Gou, M.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; et al. The antioxidant protein ZmPrx5 contributes resistance to maize stalk rot. Crop J. 2022, 10, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocianowski, J. Using NGS technology and association mapping to identify candidate genes associated with Fusarium stalk rot resistance. Genes. 2024, 15, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Han, Y.; Li, W.; Qi, T.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y. Identification of pathogens and evaluation of resistance and genetic diversity of maize inbred lines to stalk rot in Heilongjiang province, China. Plant Dis. 2023, 107, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.C.; Pei, E.Q.; Shi, Y.S.; Wang, T.Y.; Li, Y. Identification and evaluation of resistance to stalk rot (Pythium inflatum Matthews) in important inbred lines of maize. J. Plant Genet. Resour. 2012, 13, 798–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryła, M.; Pierzgalski, A.; Zapaśnik, A.; Uwineza, P.A.; Ksieniewicz-Woźniak, E.; Modrzewska, M.; Waśkiewicz, A. Recent research on Fusarium mycotoxins in maize-a review. Foods 2022, 11, 3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiedu, D.D.; Miedaner, T. Genetic and genomic tools in breeding for resistance to Fusarium stalk rot in maize (Zea mays L.). Plants 2025, 14, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiedu, D.D.; Akohoue, F.; Frank, S.; Koch, S.; Lieberherr, B.; Oyiga, B.; Miedaner, T. Comparison of four inoculation methods and three Fusarium species for phenotyping stalk rot resistance among 22 maize hybrids (Zea mays). Plant Pathol. 2024, 73, 1060–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, Z.; Babu, V.; Sharma, S.S.; Singh, P.K.; Nair, S.K. Identification and validation of a key genomic region on chromosome 6 for resistance to Fusarium stalk rot in tropical maize. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 4549–4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zheng, S.; Yu, M.; Xu, C.; Li, Y.; Sun, L.; Hu, G.H.; Yang, J.F.; Qiu, X. Evaluation of resistance resources and analysis of resistance mechanisms of maize to stalk rot caused by Fusarium graminearum. Plant Dis. 2024, 108, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, W.; Chang, F.; Yang, H.; Jiao, F.; Wang, F.; Peng, Y. Genetic analysis and identification of the candidate genes of maize resistance to Ustilago maydis by BSA-Seq and RNA-Seq. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Li, W.; Zhou, E.; Ye, X.; Li, B.; Liu, J.; Tang, J. Integrating BSA-seq with RNA-seq reveals a novel fasciated Ear5 mutant in maize. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipta, B.; Sood, S.; Mangal, V.; Bhardwaj, V.; Thakur, A.K.; Kumar, V.; Singh, B. KASP: A high-throughput genotype system and its applications in major crop plants for biotic and abiotic stress tolerance. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pè, M.E.; Gianfranceschi, L.; Taramino, G.; Tarchini, R.; Angelini, P.; Dani, M.; Binelli, G. Mapping quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for resistance to Gibberella zeae infection in maize. Mol. Genet. Genom. 1993, 241, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.E.; Zhang, C.L.; Zhang, D.S.; Jin, D.M.; Weng, M.L.; Chen, S.J.; Wang, B. Genetic analysis and molecular mapping of maize (Zea mays L.) stalk rot resistant gene Rfg1. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 108, 706–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Yin, G.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, D.; Chen, S.; Xu, M. A major QTL for resistance to Gibberella stalk rot in maize. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2010, 121, 673–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Ma, X.; Yao, L.; Liu, Y.; Du, F.; Yang, X.; Xu, M. qRfg3, a novel quantitative resistance locus against Gibberella stalk rot in maize. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2017, 130, 1723–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Liu, Y.; Guo, R.; Pacheco, A.; Muñoz-Zavala, C.; Song, W.; Zhang, X. Exploiting genomic tools for genetic dissection and improving the resistance to Fusarium stalk rot in tropical maize. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobiech, A.; Tomkowiak, A.; Nowak, B.; Bocianowski, J.; Wolko, Ł. Associative and Physical Mapping of Markers Related to Fusarium in Maize Resistance, Obtained by Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magarini, A.; Pirovano, A.; Ghidoli, M.; Cassani, E.; Casati, P.; Pilu, R. Quantitative trait loci analysis of maize husk characteristics associated with Gibberella ear rot resistance. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Sui, Y.; Yu, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, B.; Yan, J.; Duan, L. Coronatine-induced maize defense against Gibberella stalk rot by activating antioxidants and phytohormone signaling. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ruan, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, F.; Ma, L.; Gao, X. Integrated gene co-expression analysis and metabolites profiling highlight the important role of ZmHIR3 in maize resistance to Gibberella stalk rot. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 664733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Sun, Y.; Ruan, X.; Huang, P.C.; Wang, S.; Li, S.; Gao, X. Genome-wide characterization of jasmonates signaling components reveals the essential role of ZmCOI1a-ZmJAZ15 action module in regulating maize immunity to gibberella stalk rot. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, H.; Si, H.; Zang, J.; Pang, X.; Yu, L.; Cao, H.; Dong, J. Comparative proteomic analysis of the defense response to Gibberella stalk rot in maize and reveals that ZmWRKY83 is involved in plant disease resistance. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 694973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, Z.; Song, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, N.; Liu, S.; Cao, Z.; Li, H.; et al. Transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses reveal the role of phenylalanine metabolism in the maize response to stalk rot caused by Fusarium proliferatum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hou, M.; Zhang, X.; Cao, Y.; Sun, S.; Zhu, Z.; Duan, C. Integrative transcriptome and proteome analysis reveals maize responses to Fusarium verticillioides infection inside the stalks. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2023, 24, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Xu, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, X.L.; Wang, W. Multi-Omics analysis reveals a regulatory network of ZmCCT during maize resistance to Gibberella stalk rot at the early stage. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 917493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Zhong, T.; Zhang, D.; Ma, C.; Wang, L.; Yao, L.; Xu, M.L. The auxin-regulated protein ZmAuxRP1 coordinates the balance between root growth and stalk rot disease resistance in maize. Mol. Plant. 2019, 12, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrocal-Lobo, M.; Stone, S.; Yang, X.; Antico, J.; Callis, J.; Ramonell, K.M.; Somerville, S. ATL9, a RING zinc finger protein with E3 ubiquitin ligase activity implicated in chitin-and NADPH oxidase-mediated defense responses. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e14426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Xie, R.; Hu, Y.; Du, L.; Wang, F.; Zhao, X.; Liu, D. A C2H2-type zinc finger protein TaZFP8-5B negatively regulates disease resistance. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Snyder, A.; Song, W.Y. Members of the XB3 family from diverse plant species induce programmed cell death in Nicotiana benthamiana. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Song, F.; Sun, S.; Guo, C.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, X. Characterization and molecular mapping of two novel genes resistant to Pythium stalk rot in maize. Phytopathology 2019, 109, 804–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.J.; Xiao, M.G.; Duan, C.X.; Li, H.J.; Zhu, Z.D.; Liu, B.T.; Wang, X.M. Two genes conferring resistance to Pythium stalk rot in maize inbred line Qi319. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2015, 290, 1543–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Luo, M.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, H.; Li, J.; Song, W.; Zhao, J. Natural variations in the P-type ATPase heavy metal transporter gene ZmHMA3 control cadmium accumulation in maize grains. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 6230–6246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Primers | Primers Sequence | VIC | FAM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | sn6640505 | F1: GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTCAAAGGCGTCGACTCTGATAG | C | G |

| F2: GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTCAAAGGCGTCGACTCTGATAC | ||||

| R: GGAGAACATTCTGCCCCG | ||||

| 2 | sn6640608 | F1: GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTGCACGCAGAGGCATCAGT | T | G |

| F2: GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTCACGCAGAGGCATCAGG | ||||

| R: GTGTCGAACACGTCGTTGATA | ||||

| 3 | sn6639872 | F1: GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTCCCGTCTTATCTGGTGTCTCG | C | G |

| F2: GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTCCCGTCTTATCTGGTGTCTCC | ||||

| R: CTGCTTGTTATGTCTGCTGTCCTA | ||||

| 4 | sn6028745 | F1: GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTCCGGCTGATTGGCCTGA | T | C |

| F2: GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTCGGCTGATTGGCCTGG | ||||

| R: CTTCCGGTCTACAGTGGCAG | ||||

| 5 | sn5910953 | F1: GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTAAATATATAATGATTAAAGGCAAGCAC | G | A |

| F2: GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTAAATATATAATGATTAAAGGCAAGCAT | ||||

| R: GCTCAGGAAGAAGCGACCG | ||||

| 6 | sn6828750 | F1: GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTCGCTGCAAGAAGTGGAATG | G | T |

| F2: GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTCGCTGCAAGAAGTGGAATT | ||||

| R: AACCTGTCATCCGTCGTCTT | ||||

| 7 | sn5630289 | F1: GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTCACATTTTAATTGACAGTAAATTGATT | A | C |

| F2: GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTCACATTTTAATTGACAGTAAATTGATG | ||||

| R: AAGTGTCATCTCCAACCATTTCT | ||||

| 8 | sn6528233 | F1: GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTATACACCTCGATCGCCCC | G | A |

| F2: GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTCTATACACCTCGATCGCCCT | ||||

| R: TGATTTCAGGGTACGAGCAGA | ||||

| 9 | sn6843643 | F1: GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTGAGGTCTGGATCGGATGGAA | A | G |

| F2: GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTGAGGTCTGGATCGGATGGAG | ||||

| R: GCCTTTCTGCCACAATCCTT | ||||

| 10 | sn7185874 | F1: GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTGTCGCGTACAGGGGCAC | G | A |

| F2: GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTGTCGCGTACAGGGGCAT | ||||

| R: GTCGGCGGCCATGAAC | ||||

| 11 | sn5955973 | F1: GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTCGAGCATCCTGTCGCCA | A | G |

| F2: GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTCGAGCATCCTGTCGCCG | ||||

| R: GAATCTCGGCGGGAGTGA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, B.; Wang, S.; Xu, L.; Li, Z.; Ding, X.; Ma, L.; Cheng, Z.; Feng, J.; Duan, C. Gene Mapping and Genetic Analysis of Maize Resistance to Stalk Rot. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11866. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411866

Wang B, Wang S, Xu L, Li Z, Ding X, Ma L, Cheng Z, Feng J, Duan C. Gene Mapping and Genetic Analysis of Maize Resistance to Stalk Rot. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11866. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411866

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Baobao, Shaoxin Wang, Luo Xu, Zhongjian Li, Xin Ding, Liang Ma, Zixiang Cheng, Jianying Feng, and Canxing Duan. 2025. "Gene Mapping and Genetic Analysis of Maize Resistance to Stalk Rot" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11866. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411866

APA StyleWang, B., Wang, S., Xu, L., Li, Z., Ding, X., Ma, L., Cheng, Z., Feng, J., & Duan, C. (2025). Gene Mapping and Genetic Analysis of Maize Resistance to Stalk Rot. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11866. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411866