Microglial Activation in Nociplastic Pain: From Preclinical Models to PET Neuroimaging and Implications for Targeted Therapeutic Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Nociplastic Pain and Neuroinflammation

4. Microglia Activation in Preclinical Models of Nociplastic Pain

4.1. Microglial Activation—Shift Pro/Anti-Inflammatory

4.2. Preclinical Evidence of Neuroinflammation in Nociplastic Pain

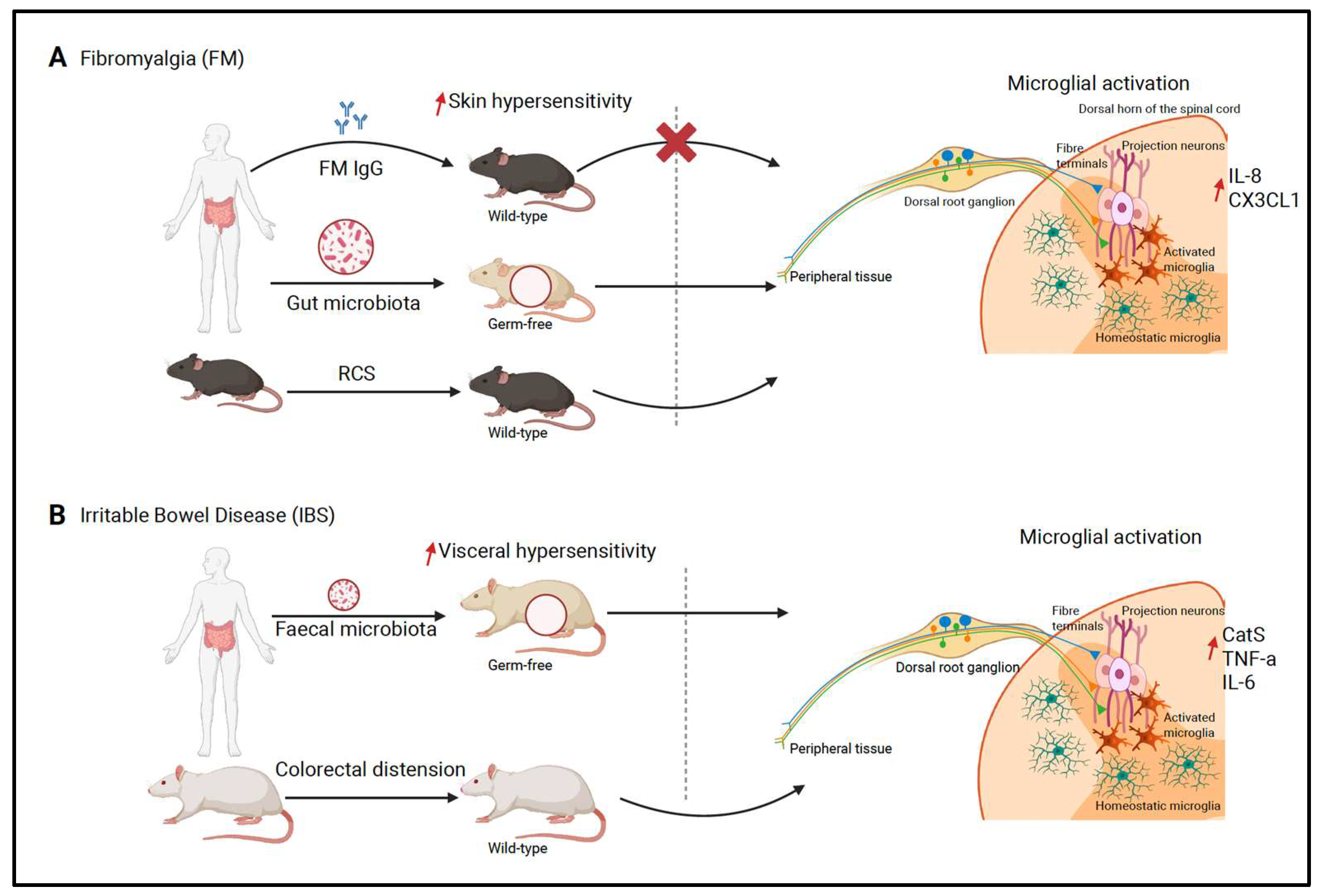

4.2.1. Fibromyalgia

4.2.2. Irritable Bowel Syndrome

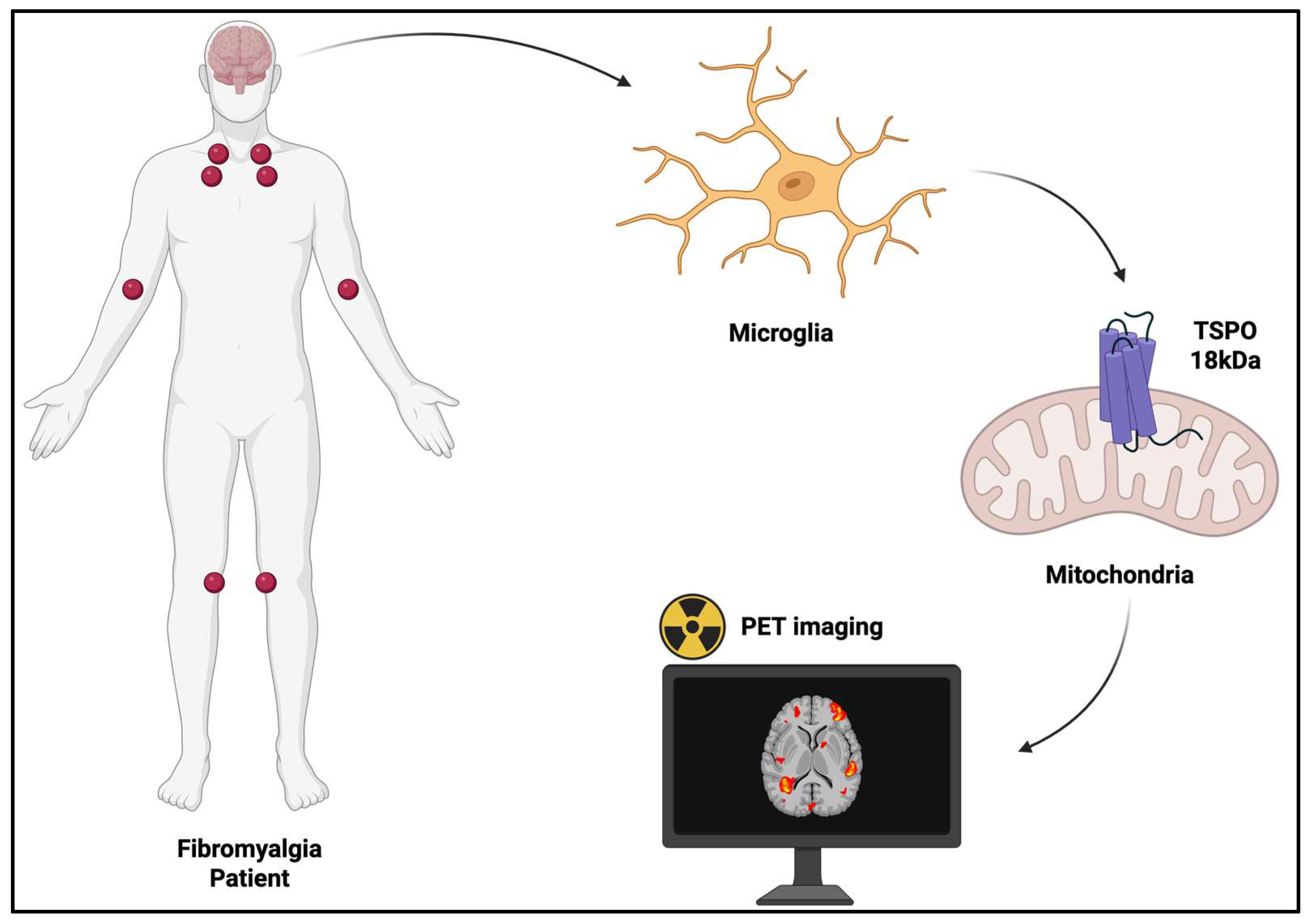

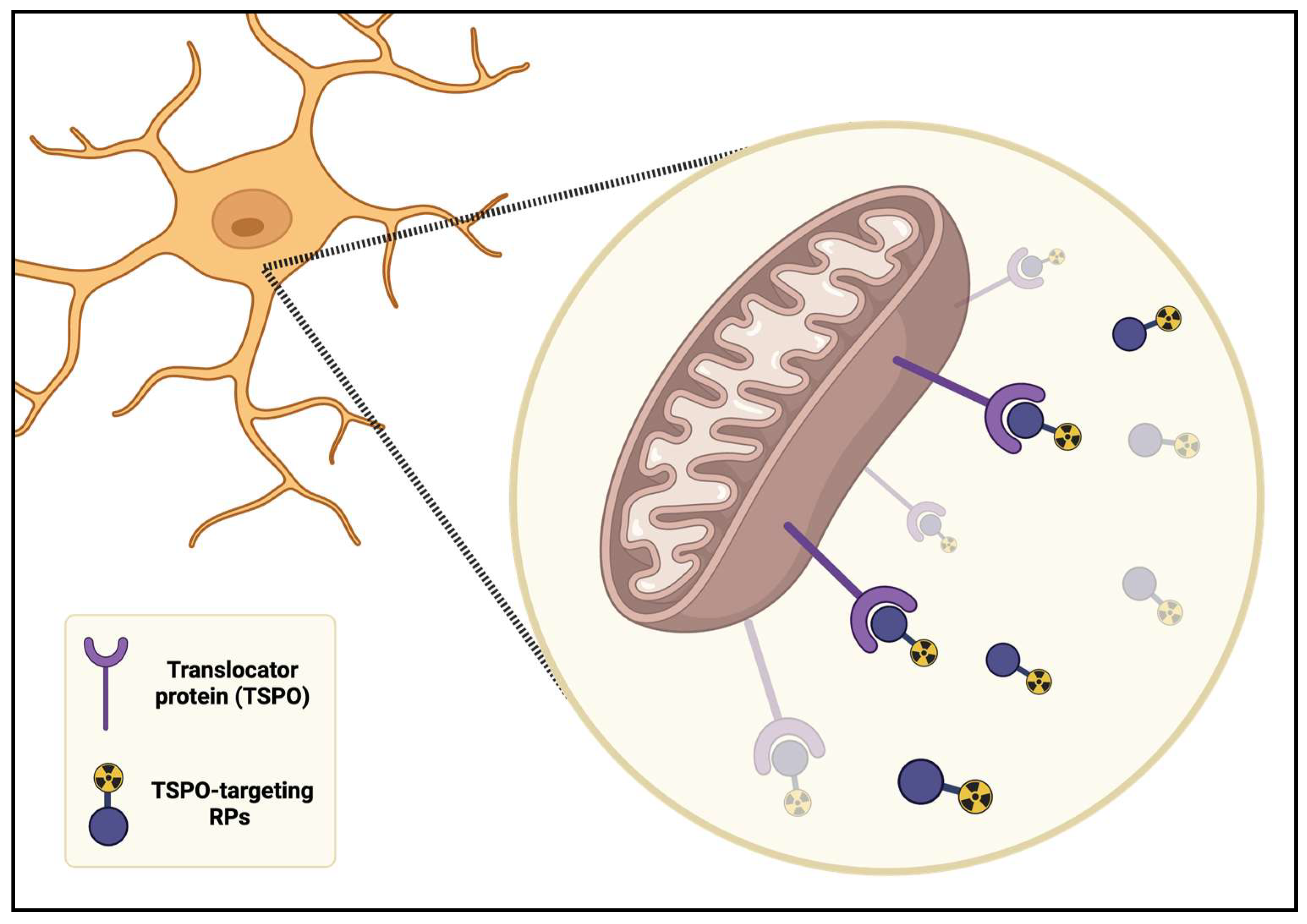

5. Microglia Activation in PET Neuroimaging

5.1. TSPO-Targeting Radiopharmaceuticals in FM

5.2. TSPO-Targeting Radiopharmaceuticals in Bowel Disease

6. Implications for Therapeutic Strategies

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | Anterior Cingulate Cortex |

| AD | Alzheimer’s Disease |

| BBB | Blood–Brain Barrier |

| BDNF | Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| CatS | Cathepsin S |

| CGRP | Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| CRPS | Complex Regional Pain Syndrome |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal Fluid |

| DLX | Duloxetine |

| FM | Fibromyalgia |

| GM | Gray Matter |

| HCs | Healthy Controls |

| IASP | International Association for the Study of Pain |

| IBS | Irritable Bowel Syndrome |

| IC | Interstitial Cystitis |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| IL | Interleukin |

| LAC | L-Acetyl Carnitine |

| mPFC | Medial Rostral Prefrontal Cortex |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MS | Multiple Sclerosis |

| NcplP | Nociplastic Pain |

| NGF | Nerve Growth Factor |

| PD | Parkinson’s Disease |

| PEA | Palmitoylethanolamide |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| PGB | Pregabalin |

| Pol | Polydatin |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| RCS | Repeated Cold Stress |

| RPs | Radiopharmaceuticals |

| TNF | Tumor Necrosis Factor |

| TSPO | Translocator Protein |

References

- Kosek, E.; Cohen, M.; Baron, R.; Gebhart, G.F.; Mico, J.-A.; Rice, A.S.C.; Rief, W.; Sluka, A.K. Do We Need a Third Mechanistic Descriptor for Chronic Pain States? Pain 2016, 157, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Blasiis, P.; de Sena, G.; Signoriello, E.; Sirico, F.; Imamura, M.; Lus, G. Nociplastic Pain in Multiple Sclerosis Spasticity: Dermatomal Evaluation, Treatment with Intradermal Saline Injection and Outcomes Assessed by 3D Gait Analysis: Review and a Case Report. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylius, V.; Möller, J.C.; Bohlhalter, S.; Ciampi de Andrade, D.; Perez Lloret, S. Diagnosis and Management of Pain in Parkinson’s Disease: A New Approach. Drugs Aging 2021, 38, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, M.D.; Haapala, H.; Kamdar, N.; Lin, P.; Hurvitz, E.A. Pain Phenotypes among Adults Living with Cerebral Palsy and Spina Bifida. Pain 2021, 162, 2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Tommaso, M.; Sciruicchio, V. Migraine and Central Sensitization: Clinical Features, Main Comorbidities and Therapeutic Perspectives. Curr. Rheumatol. Rev. 2016, 12, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, Y.; Okada-Ogawa, A.; Noma, N.; Shinozaki, T.; Watanabe, K.; Kohashi, R.; Shinoda, M.; Wada, A.; Abe, O.; Iwata, K. A Perspective from Experimental Studies of Burning Mouth Syndrome. J. Oral Sci. 2020, 62, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heir, G.M.; Ananthan, S.; Kalladka, M.; Kuchukulla, M.; Renton, T. Persistent Idiopathic Dentoalveolar Pain: Is It a Central Pain Disorder? Dent. Clin. 2023, 67, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangnus, T.J.; Dirckx, M.; Huygen, F.J. Different Types of Pain in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Require a Personalized Treatment Strategy. J. Pain Res. 2023, 16, 4379–4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcántara Montero, A.; Pacheco De Vasconcelos, S.R.; Castro Arias, A. Contextualization of the Concept of Nociplastic Pain in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2024, 116, 698–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafrir, A.L.; Martel, E.; Missmer, S.A.; Clauw, D.J.; Harte, S.E.; As-Sanie, S.; Sieberg, C.B. Pelvic Floor, Abdominal and Uterine Tenderness in Relation to Pressure Pain Sensitivity among Women with Endometriosis and Chronic Pelvic Pain. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 264, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen-Brady, K.; Fyer, A.J.; Weissman, M. The Multi-Generational Familial Aggregation of Interstitial Cystitis, Other Chronic Nociplastic Pain Disorders, Depression, and Panic Disorder. Psychol. Med. 2023, 53, 7847–7856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.J.; Asher, A.; Smith, S.R. A Targeted Approach to Post-Mastectomy Pain and Persistent Pain Following Breast Cancer Treatment. Cancers 2021, 13, 5191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leysen, L.; Adriaenssens, N.; Nijs, J.; Pas, R.; Bilterys, T.; Vermeir, S.; Lahousse, A.; Beckwée, D. Chronic Pain in Breast Cancer Survivors: Nociceptive, Neuropathic, or Central Sensitization Pain? Pain Pract. 2019, 19, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filatova, E.S.; Lila, A.M. Contribution of neurogenic mechanisms to the pathogenesis of chronic joint pain. Mod. Rheumatol. J. 2021, 15, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pain Catastrophizing Hinders Disease Activity Score 28—Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate Remission of Rheumatoid Arthritis in Patients with Normal C-Reactive Protein Levels—Yoshida—2021—International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases—Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1756-185X.14231?casa_token=vrPJAGzv8xwAAAAA%3AWeliVkVlNlth_gb2EMBGU-cZOcIayitgCXNJhTvfRv6ImyCSNdIzg1OKXeqEsrfh7oQK6Lzfb5NZO5E (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Bailly, F.; Cantagrel, A.; Bertin, P.; Perrot, S.; Thomas, T.; Lansaman, T.; Grange, L.; Wendling, D.; Dovico, C.; Trouvin, A.-P. Part of Pain Labelled Neuropathic in Rheumatic Disease Might Be Rather Nociplastic. RMD Open 2020, 6, e001326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.E.; Minhas, D.; Clauw, D.J.; Lee, Y.C. Identifying and Managing Nociplastic Pain in Individuals With Rheumatic Diseases: A Narrative Review. Arthritis Care Res. 2023, 75, 2215–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gräper, P.J.; Clark, J.R.; Thompson, B.L.; Hallegraeff, J.M. Evaluating Sensory Profiles in Nociplastic Chronic Low Back Pain: A Cross-Sectional Validation Study. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2022, 38, 1508–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrot, S. Fibromyalgia: A Misconnection in a Multiconnected World? Eur. J. Pain 2019, 23, 866–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Giorgi, V.; Marotto, D.; Atzeni, F. Fibromyalgia: An Update on Clinical Characteristics, Aetiopathogenesis and Treatment. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.P.; do Espirito Santo, A.D.S.; Berssaneti, A.A.; Matsutani, L.A.; Yuan, S.L.K. Prevalence of Fibromyalgia: Literature Review Update. Rev. Bras. Reumatol. 2017, 57, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, F.; Nanji, K.; Qidwai, W.; Qasim, R. Fibromyalgia Syndrome: An Overview of Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management. Oman Med. J. 2012, 27, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, L.A.; Robinson, R.L.; Yu, A.P.; Kaltenboeck, A.; Samuels, S.; Mallett, D.; Birnbaum, H.G. Comparison of Health Care Use and Costs in Newly Diagnosed and Established Patients with Fibromyalgia. J. Pain 2009, 10, 976–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendelman, O.; Amital, H.; Bar-On, Y.; Ben-Ami Shor, D.; Amital, D.; Tiosano, S.; Shalev, V.; Chodick, G.; Weitzman, D. Time to Diagnosis of Fibromyalgia and Factors Associated with Delayed Diagnosis in Primary Care. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2018, 32, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaffi, F.; Farah, S.; Bianchi, B.; Lommano, M.G.; Di Carlo, M. Delay in Fibromyalgia Diagnosis and Its Impact on the Severity and Outcome: A Large Cohort Study. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2024, 42, 1198–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzcharles, M.-A.; Yunus, M.B. The Clinical Concept of Fibromyalgia as a Changing Paradigm in the Past 20 Years. Pain Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 184835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macionis, V. Nociplastic Pain: Controversy of the Concept. Korean J. Pain 2025, 38, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackshaw, K.V. The Search for Biomarkers in Fibromyalgia. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, T. Nothing and Everything: Fibromyalgia as a Diagnosis of Exclusion and Inclusion. Qual. Health Res. 2019, 29, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climent-Sanz, C.; Hamilton, K.R.; Martínez-Navarro, O.; Briones-Vozmediano, E.; Gracia-Lasheras, M.; Fernández-Lago, H.; Valenzuela-Pascual, F.; Finan, P.H. Fibromyalgia Pain Management Effectiveness from the Patient Perspective: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2024, 46, 4595–4610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loggia, M.L. “Neuroinflammation”: Does It Have a Role in Chronic Pain? Evidence from Human Imaging. Pain 2024, 165, S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Qadri, Y.J.; Serhan, C.N.; Ji, R.-R. Microglia in Pain: Detrimental and Protective Roles in Pathogenesis and Resolution of Pain. Neuron 2018, 100, 1292–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.-R.; Nackley, A.; Huh, Y.; Terrando, N.; Maixner, W. Neuroinflammation and Central Sensitization in Chronic and Widespread Pain. Anesthesiology 2018, 129, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasui, M.; Yoshimura, T.; Takeuchi, S.; Tokizane, K.; Tsuda, M.; Inoue, K.; Kiyama, H. A Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Model Demonstrates Mechanical Allodynia and Muscular Hyperalgesia via Spinal Microglial Activation. Glia 2014, 62, 1407–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydede, M.; Shriver, A. Recently Introduced Definition of “Nociplastic Pain” by the International Association for the Study of Pain Needs Better Formulation. Pain 2018, 159, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzcharles, M.-A.; Cohen, S.P.; Clauw, D.J.; Littlejohn, G.; Usui, C.; Häuser, W. Nociplastic Pain: Towards an Understanding of Prevalent Pain Conditions. Lancet 2021, 397, 2098–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraga, S.; Itokazu, T.; Nishibe, M.; Yamashita, T. Neuroplasticity Related to Chronic Pain and Its Modulation by Microglia. Inflamm. Regen. 2022, 42, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popkirov, S.; Enax-Krumova, E.K.; Mainka, T.; Hoheisel, M.; Hausteiner-Wiehle, C. Functional Pain Disorders—More than Nociplastic Pain. NeuroRehabilitation 2020, 47, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshelh, Z.; Brusaferri, L.; Saha, A.; Morrissey, E.; Knight, P.; Kim, M.; Zhang, Y.; Hooker, J.M.; Albrecht, D.; Torrado-Carvajal, A.; et al. Neuroimmune Signatures in Chronic Low Back Pain Subtypes. Brain 2022, 145, 1098–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashmi, J.A.; Baliki, M.N.; Huang, L.; Baria, A.T.; Torbey, S.; Hermann, K.M.; Schnitzer, T.J.; Apkarian, A.V. Shape Shifting Pain: Chronification of Back Pain Shifts Brain Representation from Nociceptive to Emotional Circuits. Brain 2013, 136, 2751–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankerd, K.; McDonough, K.E.; Wang, J.; Tang, S.-J.; Chung, J.M.; La, J.-H. Postinjury Stimulation Triggers a Transition to Nociplastic Pain in Mice. Pain 2022, 163, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorupska, E.; Jokiel, M.; Rychlik, M.; Łochowski, R.; Kotwicka, M. Female Overrepresentation in Low Back-Related Leg Pain: A Retrospective Study of the Autonomic Response to a Minimally Invasive Procedure. J. Pain Res. 2020, 13, 3427–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocay, D.D.; Ross, B.D.; Moscaritolo, L.; Ahmed, N.; Ouellet, J.A.; Ferland, C.E.; Ingelmo, P.M. The Psychosocial Characteristics and Somatosensory Function of Children and Adolescents Who Meet the Criteria for Chronic Nociplastic Pain. J. Pain Res. 2023, 16, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.-M.; Kim, K.-H. Current Understanding of Nociplastic Pain. Korean J. Pain 2024, 37, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendieta, D.; la Cruz-Aguilera, D.L.D.; Barrera-Villalpando, M.I.; Becerril-Villanueva, E.; Arreola, R.; Hernández-Ferreira, E.; Pérez-Tapia, S.M.; Pérez-Sánchez, G.; Garcés-Alvarez, M.E.; Aguirre-Cruz, L.; et al. IL-8 and IL-6 Primarily Mediate the Inflammatory Response in Fibromyalgia Patients. J. Neuroimmunol. 2016, 290, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Tsilioni, I.; Bawazeer, M. Mast Cells, Neuroinflammation and Pain in Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, I.J.; Orr, M.D.; Littman, B.; Vipraio, G.A.; Alboukrek, D.; Michalek, J.E.; Lopez, Y.; Mackillip, F. Elevated Cerebrospinal Fluid Levels of Substance p in Patients with the Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1994, 37, 1593–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarchielli, P.; Mancini, M.L.; Floridi, A.; Coppola, F.; Rossi, C.; Nardi, K.; Acciarresi, M.; Pini, L.A.; Calabresi, P. Increased Levels of Neurotrophins Are Not Specific for Chronic Migraine: Evidence From Primary Fibromyalgia Syndrome. J. Pain 2007, 8, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jablochkova, A.; Bäckryd, E.; Kosek, E.; Mannerkorpi, K.; Ernberg, M.; Gerdle, B.; Ghafouri, B. Unaltered Low Nerve Growth Factor and High Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Levels in Plasma from Patients with Fibromyalgia after a 15-Week Progressive Resistance Exercise. J. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 51, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laske, C.; Stransky, E.; Eschweiler, G.W.; Klein, R.; Wittorf, A.; Leyhe, T.; Richartz, E.; Köhler, N.; Bartels, M.; Buchkremer, G.; et al. Increased BDNF Serum Concentration in Fibromyalgia with or without Depression or Antidepressants. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2007, 41, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, D.; Eich, W.; Saft, S.; Geisel, O.; Hellweg, R.; Finn, A.; Svensson, C.I.; Tesarz, J. No Evidence for Altered Plasma NGF and BDNF Levels in Fibromyalgia Patients. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidari, A.; Ghavidel-Parsa, B.; Gharibpoor, F. Comparison of the Serum Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) between Fibromyalgia and Nociceptive Pain Groups; and Effect of Duloxetine on the BDNF Level. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosek, E.; Altawil, R.; Kadetoff, D.; Finn, A.; Westman, M.; Le Maître, E.; Andersson, M.; Jensen-Urstad, M.; Lampa, J. Evidence of Different Mediators of Central Inflammation in Dysfunctional and Inflammatory Pain—Interleukin-8 in Fibromyalgia and Interleukin-1 β in Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Neuroimmunol. 2015, 280, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehlik, R.; Ulfberg, J. (Neuro)Inflammatory Component May Be a Common Factor in Chronic Widespread Pain and Restless Legs Syndrome. Curr. Sleep Med. Rep. 2020, 6, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Nijs, J.; Neblett, R.; Polli, A.; Moens, M.; Goudman, L.; Shekhar Patil, M.; Knaggs, R.D.; Pickering, G.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Phenotyping Post-COVID Pain as a Nociceptive, Neuropathic, or Nociplastic Pain Condition. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, D.N.; Sá, K.N.; Queirós, F.C.; Paixão, A.B.; Santos, K.O.B.; de Andrade, R.C.P.; Camatti, J.R.; Baptista, A.F. Pain, Psychoaffective Symptoms, and Quality of Life in Human T Cell Lymphotropic Virus Type 1 (HTLV-1): A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Neurovirol. 2021, 27, 838–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabacof, L.; Chiplunkar, M.; Canori, A.; Howard, R.; Wood, J.; Proal, A.; Putrino, D. Distinguishing Pain Profiles among Individuals with Long COVID. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2024, 5, 1448816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauw, D.J.; Häuser, W.; Cohen, S.P.; Fitzcharles, M.-A. Considering the Potential for an Increase in Chronic Pain after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pain 2020, 161, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, J.; Lepra, M.; Kish, S.J.; Rusjan, P.M.; Nasser, Z.; Verhoeff, N.; Vasdev, N.; Bagby, M.; Boileau, I.; Husain, M.I.; et al. Neuroinflammation After COVID-19 With Persistent Depressive and Cognitive Symptoms. JAMA Psychiatry 2023, 80, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinho-Ribeiro, F.A.; Verri, W.A.; Chiu, I.M. Nociceptor Sensory Neuron–Immune Interactions in Pain and Inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2017, 38, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malcangio, M. Role of the Immune System in Neuropathic Pain. Scand. J. Pain 2020, 20, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clauw, D.J. Fibromyalgia: A Clinical Review. JAMA 2014, 311, 1547–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.S.; Sherif, M.; Alghamdi, M.A.; El-Tallawy, S.N.; Alzaydan, O.K.; Pergolizzi, J.V.; Varrassi, G.; Zaghra, Z.; Abdelsalam, Z.S.; Kamal, M.T.; et al. Exploring the Immune System’s Role in Endometriosis: Insights Into Pathogenesis, Pain, and Treatment. Cureus 2025, 17, e87091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergolizzi, J.V., Jr.; LeQuang, J.A.; Coluzzi, F.; El-Tallawy, S.N.; Magnusson, P.; Ahmed, R.S.; Varrassi, G.; Porpora, M.G. Managing the Neuroinflammatory Pain of Endometriosis in Light of Chronic Pelvic Pain. Expert. Opin. Pharmacother. 2024, 25, 2267–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, F.; Rocco, M.; Luongo, L.; Persiani, P.; Vulpiani, M.C.; Nusca, S.M.; Maione, S.; Coluzzi, F. Targeting Neuroinflammation in Osteoarthritis with Intra-Articular Adelmidrol. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Agnelli, S.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Gerra, M.C.; Zatorri, K.; Boggiani, L.; Baciarello, M.; Bignami, E. Fibromyalgia: Genetics and Epigenetics Insights May Provide the Basis for the Development of Diagnostic Biomarkers. Mol. Pain 2019, 15, 1744806918819944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovrom, E.A.; Mostert, K.A.; Khakhkhar, S.; McKee, D.P.; Yang, P.; Her, Y.F. A Comprehensive Review of the Genetic and Epigenetic Contributions to the Development of Fibromyalgia. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morlion, B.; Coluzzi, F.; Aldington, D.; Kocot-Kepska, M.; Pergolizzi, J.; Mangas, A.C.; Ahlbeck, K.; Kalso, E. Pain Chronification: What Should a Non-Pain Medicine Specialist Know? Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2018, 34, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.-Y.; Svensson, C.I.; Matsui, T.; Fitzsimmons, B.; Yaksh, T.L.; Webb, M. Intrathecal Minocycline Attenuates Peripheral Inflammation-Induced Hyperalgesia by Inhibiting P38 MAPK in Spinal Microglia. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2005, 22, 2431–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorge, R.E.; Mapplebeck, J.C.S.; Rosen, S.; Beggs, S.; Taves, S.; Alexander, J.K.; Martin, L.J.; Austin, J.-S.; Sotocinal, S.G.; Chen, D.; et al. Different Immune Cells Mediate Mechanical Pain Hypersensitivity in Male and Female Mice. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 1081–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcangio, M.; Sideris-Lampretsas, G. A Look into the Future: Your Biological Sex May Guide Chronic Pain Treatment. Neuron 2025, 113, 800–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcangio, M.; Sideris-Lampretsas, G. How Microglia Contribute to the Induction and Maintenance of Neuropathic Pain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2025, 26, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohno, K.; Shirasaka, R.; Yoshihara, K.; Mikuriya, S.; Tanaka, K.; Takanami, K.; Inoue, K.; Sakamoto, H.; Ohkawa, Y.; Masuda, T.; et al. A Spinal Microglia Population Involved in Remitting and Relapsing Neuropathic Pain. Science 2022, 376, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosek, E. The Concept of Nociplastic Pain—Where to from Here? Pain 2024, 165, S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Muley, M.M.; Beggs, S.; Salter, M.W. Microglia-Independent Peripheral Neuropathic Pain in Male and Female Mice. Pain 2022, 163, e1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakatsuki, K.; Kiryu-Seo, S.; Yasui, M.; Yokota, H.; Kida, H.; Konishi, H.; Kiyama, H. Repeated Cold Stress, an Animal Model for Fibromyalgia, Elicits Proprioceptor-Induced Chronic Pain with Microglial Activation in Mice. J. Neuroinflamm. 2024, 21, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erny, D.; Hrabě de Angelis, A.L.; Jaitin, D.; Wieghofer, P.; Staszewski, O.; David, E.; Keren-Shaul, H.; Mahlakoiv, T.; Jakobshagen, K.; Buch, T.; et al. Host Microbiota Constantly Control Maturation and Function of Microglia in the CNS. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertz, H.; Naliboff, B.; Munakata, J.; Niazi, N.; Mayer, E.A. Altered Rectal Perception Is a Biological Marker of Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterology 1995, 109, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhao, B.-X.; Hua, R.; Kang, J.; Shao, B.-M.; Carbonaro, T.M.; Zhang, Y.-M. Hippocampal Microglial Activation and Glucocorticoid Receptor Down-Regulation Precipitate Visceral Hypersensitivity Induced by Colorectal Distension in Rats. Neuropharmacology 2016, 102, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucarini, E.; Parisio, C.; Branca, J.J.V.; Segnani, C.; Ippolito, C.; Pellegrini, C.; Antonioli, L.; Fornai, M.; Micheli, L.; Pacini, A.; et al. Deepening the Mechanisms of Visceral Pain Persistence: An Evaluation of the Gut-Spinal Cord Relationship. Cells 2020, 9, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, T.; Manohar, K.; Latorre, R.; Orock, A.; Greenwood-Van Meerveld, B. Inhibition of Microglial Activation in the Amygdala Reverses Stress-Induced Abdominal Pain in the Male Rat. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 10, 527–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atmani, K.; Wuestenberghs, F.; Baron, M.; Bouleté, I.; Guérin, C.; Bahlouli, W.; Vaudry, D.; do Rego, J.C.; Cornu, J.-N.; Leroi, A.-M.; et al. Bladder-Colon Chronic Cross-Sensitization Involves Neuro-Glial Pathways in Male Mice. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 6935–6949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, N.-N.; Meng, Q.-X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.-M.; Song, Y.; Hua, R.; Zhang, Y.-M. Microglia-Derived TNF-α Inhibiting GABAergic Neurons in the Anterior Lateral Bed Nucleus of the Stria Terminalis Precipitates Visceral Hypersensitivity Induced by Colorectal Distension in Rats. Neurobiol. Stress 2022, 18, 100449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Zhu, S.; Fang, Y.; Wang, B.; Jia, Q.; Hao, H.; Kao, J.Y.; He, Q.; Song, L.; et al. Berberine Alleviates Visceral Hypersensitivity in Rats by Altering Gut Microbiome and Suppressing Spinal Microglial Activation. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2021, 42, 1821–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, P.; Lin, W.; Weng, Y.; Gong, J.; Huang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Lin, C.; Chen, A.; Chen, Y. Spinal Cathepsin S Promotes Visceral Hypersensitivity via FKN/CX3CR1/P38 MAPK Signaling Pathways. Mol. Pain 2023, 19, 17448069231179118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.K.; Malcangio, M. Microglial Signalling Mechanisms: Cathepsin S and Fractalkine. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 234, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, E.A.; Labus, J.; Aziz, Q.; Tracey, I.; Kilpatrick, L.; Elsenbruch, S.; Schweinhardt, P.; Oudenhove, L.V.; Borsook, D. Role of Brain Imaging in Disorders of Brain–Gut Interaction: A Rome Working Team Report. Gut 2019, 68, 1701–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, X.; Huang, S.; Wang, H.; Shen, G. Low-Level Inflammation, Immunity, and Brain-Gut Axis in IBS: Unraveling the Complex Relationships. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2263209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworsky-Fried, Z.; Kerr, B.J.; Taylor, A.M.W. Microbes, Microglia, and Pain. Neurobiol. Pain 2020, 7, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, V.; Pupi, A.; Mosconi, L. PET/CT in Diagnosis of Dementia. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1228, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, V.; Pupi, A.; Mosconi, L. PET/CT in Diagnosis of Movement Disorders. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1228, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Liu, X.; Yu, T.; Ren, J.; Wang, Q. Positron Emission Tomography in Autoimmune Encephalitis: Clinical Implications and Future Directions. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2022, 146, 708–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abenavoli, E.; Berti, V.; Nerattini, M.; Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Filippou, G.; Lucia, A.; Pari, G.; Pallanti, S.; Salaffi, F.; Carotti, M.; et al. Fibromyalgia in the Era of Brain PET/CT Imaging. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, D.R.J.; Matthews, P.M. Imaging Brain Microglial Activation Using Positron Emission Tomography and Translocator Protein-Specific Radioligands. In International Review of Neurobiology; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Volume 101, pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse, R.N. Determination of Lipophilicity and Its Use as a Predictor of Blood–Brain Barrier Penetration of Molecular Imaging Agents. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2003, 5, 376–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, C.; Jenko, K.; Zoghbi, S.S.; Innis, R.B.; Pike, V.W. Development of N-Methyl-(2-Arylquinolin-4-Yl)Oxypropanamides as Leads to PET Radioligands for Translocator Protein (18 kDa). J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 6240–6251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berroterán-Infante, N.; Kalina, T.; Fetty, L.; Janisch, V.; Velasco, R.; Vraka, C.; Hacker, M.; Haug, A.R.; Pallitsch, K.; Wadsak, W.; et al. (R)-[18F]NEBIFQUINIDE: A Promising New PET Tracer for TSPO Imaging. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 176, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, S.; Viviano, M.; Baglini, E.; Poggetti, V.; Giorgini, D.; Castagnoli, J.; Barresi, E.; Castellano, S.; Da Settimo, F.; Taliani, S. TSPO Radioligands for Neuroinflammation: An Overview. Molecules 2024, 29, 4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutin, H.; Prenant, C.; Maroy, R.; Galea, J.; Greenhalgh, A.D.; Smigova, A.; Cawthorne, C.; Julyan, P.; Wilkinson, S.M.; Banister, S.D.; et al. [18F]DPA-714: Direct Comparison with [11C]PK11195 in a Model of Cerebral Ischemia in Rats. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, D.S.; Forsberg, A.; Sandström, A.; Bergan, C.; Kadetoff, D.; Protsenko, E.; Lampa, J.; Lee, Y.C.; Höglund, C.O.; Catana, C.; et al. Brain Glial Activation in Fibromyalgia—A Multi-Site Positron Emission Tomography Investigation. Brain Behav. Immun. 2019, 75, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, S.; Jung, Y.-H.; Lee, D.; Lee, W.J.; Jang, J.H.; Lee, J.-Y.; Choi, S.-H.; Moon, J.Y.; Lee, J.S.; Cheon, G.J.; et al. Abnormal Neuroinflammation in Fibromyalgia and CRPS Using [11C]-(R)-PK11195 PET. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, C.; Fang, Y.-H.D.; Jones, C.; McConathy, J.E.; Raman, F.; Lapi, S.E.; Younger, J.W. Evidence of Neuroinflammation in Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A [18F]DPA-714 Positron Emission Tomography Study. Pain 2023, 164, 2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimura, D.; Shinohara, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Sugimura, Y.K.; Sugimoto, M.; Tsurugizawa, T.; Marumo, K.; Kato, F. Primary Role of the Amygdala in Spontaneous Inflammatory Pain- Associated Activation of Pain Networks—A Chemogenetic Manganese-Enhanced MRI Approach. Front. Neural Circuits 2019, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Yue, L.; Liu, S.; Xu, S.; Tong, J.; Sun, X.; Su, L.; Cui, S.; Liu, F.-Y.; Wan, Y.; et al. A Distinct Neuronal Ensemble of Prelimbic Cortex Mediates Spontaneous Pain in Rats with Peripheral Inflammation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, D.S.; Kim, M.; Akeju, O.; Torrado-Carvajal, A.; Edwards, R.R.; Zhang, Y.; Bergan, C.; Protsenko, E.; Kucyi, A.; Wasan, A.D.; et al. The Neuroinflammatory Component of Negative Affect in Patients with Chronic Pain. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 864–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, L.; Li, B.; Feng, N.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Lu, H.; Yin, H. Decreased Triple Network Connectivity in Patients with Recent Onset Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder after a Single Prolonged Trauma Exposure. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.-J.; Luo, E.-P.; Lu, H.-B.; Yin, H. Cortical Thinning in Patients with Recent Onset Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder after a Single Prolonged Trauma Exposure. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fülöp, B.; Hunyady, Á.; Bencze, N.; Kormos, V.; Szentes, N.; Dénes, Á.; Lénárt, N.; Borbély, É.; Helyes, Z. IL-1 Mediates Chronic Stress-Induced Hyperalgesia Accompanied by Microglia and Astroglia Morphological Changes in Pain-Related Brain Regions in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosek, E.; Martinsen, S.; Gerdle, B.; Mannerkorpi, K.; Löfgren, M.; Bileviciute-Ljungar, I.; Fransson, P.; Schalling, M.; Ingvar, M.; Ernberg, M.; et al. The Translocator Protein Gene Is Associated with Symptom Severity and Cerebral Pain Processing in Fibromyalgia. Brain Behav. Immun. 2016, 58, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanton, S.; Sandström, A.; Tour, J.; Kadetoff, D.; Schalling, M.; Jensen, K.B.; Sitnikov, R.; Ellerbrock, I.; Kosek, E. The Translocator Protein Gene Is Associated with Endogenous Pain Modulation and the Balance between Glutamate and γ-Aminobutyric Acid in Fibromyalgia and Healthy Subjects: A Multimodal Neuroimaging Study. Pain 2022, 163, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernards, N.; Pottier, G.; Thézé, B.; Dollé, F.; Boisgard, R. In Vivo Evaluation of Inflammatory Bowel Disease with the Aid of μPET and the Translocator Protein 18 kDa Radioligand [18F]DPA-714. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2015, 17, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.; Wu, X.-H.; Jiang, D.-L.; Lin, R.-T.; Xie, F.; Guan, Y.-H.; Fei, A.-H. Translocator Protein Facilitates Neutrophil-Mediated Mucosal Inflammation in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 31, 109239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostuni, M.A.; Issop, L.; Péranzi, G.; Walker, F.; Fasseu, M.; Elbim, C.; Papadopoulos, V.; Lacapere, J.-J. Overexpression of Translocator Protein in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Potential Diagnostic and Treatment Value. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2010, 16, 1476–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Largeau, B.; Dupont, A.-C.; Guilloteau, D.; Santiago-Ribeiro, M.-J.; Arlicot, N. TSPO PET Imaging: From Microglial Activation to Peripheral Sterile Inflammatory Diseases? Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2017, 2017, 6592139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Han, J.; Xu, Y.; Cai, M.; Gao, F.; Han, J.; Wang, D.; Fu, Y.; Chen, H.; He, W.; et al. TSPO Deficiency Exacerbates GSDMD-Mediated Macrophage Pyroptosis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Cells 2022, 11, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, W.E.; Duffy, K.; Sharpe, J.; Nabata, T.; Bruce, M. Randomised Clinical Trial: Exploratory Phase 2 Study of ONO-2952 in Diarrhoea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 45, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, V.; Steardo, L.; D’Angelo, M.; Monaco, F.; Steardo, L. Palmitoylethanolamide: A Multifunctional Molecule for Neuroprotection, Chronic Pain, and Immune Modulation. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurlyandchik, I.; Lauche, R.; Tiralongo, E.; Warne, L.N.; Schloss, J. Plasma and Interstitial Levels of Endocannabinoids and N-Acylethanolamines in Patients with Chronic Widespread Pain and Fibromyalgia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pain Rep. 2022, 7, e1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skaper, S.D.; Facci, L.; Giusti, P. Glia and Mast Cells as Targets for Palmitoylethanolamide, an Anti-Inflammatory and Neuroprotective Lipid Mediator. Mol. Neurobiol. 2013, 48, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skaper, S.D.; Facci, L. Mast Cell–Glia Axis in Neuroinflammation and Therapeutic Potential of the Anandamide Congener Palmitoylethanolamide. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2012, 367, 3312–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosino, P.; Soldovieri, M.V.; Russo, C.; Taglialatela, M. Activation and Desensitization of TRPV1 Channels in Sensory Neurons by the PPARα Agonist Palmitoylethanolamide. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 168, 1430–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, F.; Luongo, L.; Boccella, S.; Giordano, M.E.; Romano, R.; Bellini, G.; Manzo, I.; Furiano, A.; Rizzo, A.; Imperatore, R.; et al. Palmitoylethanolamide Induces Microglia Changes Associated with Increased Migration and Phagocytic Activity: Involvement of the CB2 Receptor. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luongo, L.; Guida, F.; Boccella, S.; Bellini, G.; Gatta, L.; Rossi, F.; de Novellis, V.; Maione, S. Palmitoylethanolamide Reduces Formalin-Induced Neuropathic-Like Behaviour Through Spinal Glial/Microglial Phenotypical Changes in Mice. CNS Neurol. Disord.-Drug Targets 2013, 12, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, F.; Luongo, L.; Marmo, F.; Romano, R.; Iannotta, M.; Napolitano, F.; Belardo, C.; Marabese, I.; D’Aniello, A.; De Gregorio, D.; et al. Palmitoylethanolamide Reduces Pain-Related Behaviors and Restores Glutamatergic Synapses Homeostasis in the Medial Prefrontal Cortex of Neuropathic Mice. Mol. Brain 2015, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiano, C.; Avagliano, C.; Cuozzo, M.; Liguori, F.M.; Calignano, A.; Russo, R. The Beneficial Effects of Ultramicronized Palmitoylethanolamide in the Management of Neuropathic Pain and Associated Mood Disorders Induced by Paclitaxel in Mice. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landolfo, E.; Cutuli, D.; Petrosini, L.; Caltagirone, C. Effects of Palmitoylethanolamide on Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Review from Rodents to Humans. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giorno, R.; Skaper, S.; Paladini, A.; Varrassi, G.; Coaccioli, S. Palmitoylethanolamide in Fibromyalgia: Results from Prospective and Retrospective Observational Studies. Pain Ther. 2015, 4, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweiger, V.; Martini, A.; Bellamoli, P.; Donadello, K.; Schievano, C.; Balzo, G.D.; Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Parolini, M.; Polati, E. Ultramicronized Palmitoylethanolamide (Um-PEA) as Add-on Treatment in Fibromyalgia Syndrome (FMS): Retrospective Observational Study on 407 Patients. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2019, 18, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaffi, F.; Farah, S.; Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Di Carlo, M. Palmitoylethanolamide and Acetyl-L-Carnitine Act Synergistically with Duloxetine and Pregabalin in Fibromyalgia: Results of a Randomised Controlled Study. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2023, 41, 1323–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentivenga, C.; Cicero, A.F.G.; Fogacci, F.; Politi, N.E.; Di Micoli, A.; Cosentino, E.R.; Gionchetti, P.; Borghi, C. Retrospective Evaluation of L-Acetyl Carnitine and Palmitoylethanolamide as Add-On Therapy in Patients with Fibromyalgia and Small Fiber Neuropathy. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhn, P.; Christensen, R.; Locht, H.; Henriksen, M.; Ginnerup-Nielsen, E.; Bliddal, H.; Wæhrens, E.; Thielen, K.; Amris, K. Phenotypic Characteristics of Patients with Chronic Widespread Pain and Fibromyalgia: A Cross-Sectional Cluster Analysis. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2024, 53, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnern, M.M.; Kleinböhl, D.; Flor, H.; Benrath, J.; Hölzl, R. Differential Sensory and Clinical Phenotypes of Patients with Chronic Widespread and Regional Musculoskeletal Pain. Pain 2021, 162, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremon, C.; Stanghellini, V.; Barbaro, M.R.; Cogliandro, R.F.; Bellacosa, L.; Santos, J.; Vicario, M.; Pigrau, M.; Alonso Cotoner, C.; Lobo, B.; et al. Randomised Clinical Trial: The Analgesic Properties of Dietary Supplementation with Palmitoylethanolamide and Polydatin in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 45, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nardo, G.; Bernardo, L.; Cremon, C.; Barbara, G.; Felici, E.; Evangelisti, M.; Ferretti, A.; Furio, S.; Piccirillo, M.; Coluzzi, F.; et al. Palmitoylethanolamide and Polydatin in Pediatric Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Multicentric Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrition 2024, 122, 112397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, C.M.; Kelleher, E.; Irani, A.; Schrepf, A.; Clauw, D.J.; Harte, S.E. Deciphering Nociplastic Pain: Clinical Features, Risk Factors and Potential Mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2024, 20, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bułdyś, K.; Górnicki, T.; Kałka, D.; Szuster, E.; Biernikiewicz, M.; Markuszewski, L.; Sobieszczańska, M. What Do We Know about Nociplastic Pain? Healthcare 2023, 11, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebke, K.B.; McCarberg, B.; Shaw, E.; Turk, D.C.; Wright, W.L.; Semel, D. A Practical Guide to Recognize, Assess, Treat and Evaluate (RATE) Primary Care Patients with Chronic Pain. Postgrad. Med. 2023, 135, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauw, D.J. Quantitative Sensory Testing in Nociplastic Pain: What Should We Be Looking for and What Does It Tell Us? Pain 2025, 166, 2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosek, E.; Clauw, D.; Nijs, J.; Baron, R.; Gilron, I.; Harris, R.E.; Mico, J.-A.; Rice, A.S.C.; Sterling, M. Chronic Nociplastic Pain Affecting the Musculoskeletal System: Clinical Criteria and Grading System. Pain 2021, 162, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijs, J.; Lahousse, A.; Kapreli, E.; Bilika, P.; Saraçoğlu, İ.; Malfliet, A.; Coppieters, I.; De Baets, L.; Leysen, L.; Roose, E.; et al. Nociplastic Pain Criteria or Recognition of Central Sensitization? Pain Phenotyping in the Past, Present and Future. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, A.A.; Ibrahim, W.W.; Mohamed, A.F.; Abdelkader, N.F. Microglia Polarization in Nociplastic Pain: Mechanisms and Perspectives. Inflammopharmacol 2023, 31, 1053–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signore, A.; Glaudemans, A.W.J.M.; Galli, F.; Rouzet, F. Imaging Infection and Inflammation. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 615150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, K.; Ogawa, M.; Ji, B.; Watabe, T.; Zhang, M.-R.; Suzuki, H.; Sawada, M.; Nishi, K.; Kudo, T. Basic Science of PET Imaging for Inflammatory Diseases. In PET/CT for Inflammatory Diseases: Basic Sciences, Typical Cases, and Review; Toyama, H., Li, Y., Hatazawa, J., Huang, G., Kubota, K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 1–42. ISBN 978-981-15-0810-3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Gao, X.; Chen, X.; Li, L.; Li, G.; Liu, C.; Miao, Y.; Wang, R.; Hu, K. Radiopharmaceuticals and Their Applications in Medicine. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgio, A.; Del Gatto, A.; Pennacchio, S.; Saviano, M.; Zaccaro, L. Peptoids: Smart and Emerging Candidates for the Diagnosis of Cancer, Neurological and Autoimmune Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blok, D.; Feitsma, R.I.J.; Vermeij, P.; Pauwels, E.J.K. Peptide Radiopharmaceuticals in Nuclear Medicine. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 1999, 26, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, J.E.; Guimarães, I. Fibromyalgia—Are There Any New Approaches? Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2024, 38, 101933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.; Luo, Y.; Liang, X.; Tang, J.; Wang, J.; Xiao, Q.; Qi, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhu, P.; Yang, H.; et al. Beneficial Effects of Running Exercise on Hippocampal Microglia and Neuroinflammation in Chronic Unpredictable Stress-Induced Depression Model Rats. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Su, Z. Effects of Exercise on Neuroinflammation in Age-Related Neurodegenerative Disorders. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Alventosa, R.; Inglés, M.; Cortés-Amador, S.; Gimeno-Mallench, L.; Chirivella-Garrido, J.; Kropotov, J.; Serra-Añó, P. Low-Intensity Physical Exercise Improves Pain Catastrophizing and Other Psychological and Physical Aspects in Women with Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés-Rodríguez, L.; Borràs, X.; Feliu-Soler, A.; Pérez-Aranda, A.; Rozadilla-Sacanell, A.; Montero-Marin, J.; Maes, M.; Luciano, J.V. Immune-Inflammatory Pathways and Clinical Changes in Fibromyalgia Patients Treated with Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR): A Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. Brain Behav. Immun. 2019, 80, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardy, K.; Klose, P.; Busch, A.J.; Choy, E.H.; Häuser, W. Cognitive Behavioural Therapies for Fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD009796. [Google Scholar]

- Glombiewski, J.A.; Sawyer, A.T.; Gutermann, J.; Koenig, K.; Rief, W.; Hofmann, S.G. Psychological Treatments for Fibromyalgia: A Meta-Analysis. Pain 2010, 151, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnum, C.J.; Pace, T.W.; Hu, F.; Neigh, G.N.; Tansey, M.G. Psychological Stress in Adolescent and Adult Mice Increases Neuroinflammation and Attenuates the Response to LPS Challenge. J. Neuroinflamm. 2012, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, G.J.; Kronisch, C.; Dean, L.E.; Atzeni, F.; Häuser, W.; Fluß, E.; Choy, E.; Kosek, E.; Amris, K.; Branco, J.; et al. EULAR Revised Recommendations for the Management of Fibromyalgia. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derry, S.; Wiffen, P.J.; Häuser, W.; Mücke, M.; Tölle, T.R.; Bell, R.F.; Moore, R.A. Oral Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs for Fibromyalgia in Adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 3, CD012332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrot, S. Fibromyalgia: Do I Tackle You with Pharmacological Treatments? Pain Rep. 2025, 10, e1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, I.; Robles, C.; Peiró, S.; García-Sempere, A.; Llopis, F.; Sánchez, F.; Rodríguez-Bernal, C.; Sanfélix, G. Long versus Short-Term Opioid Therapy for Fibromyalgia Syndrome and Risk of Depression, Sleep Disorders and Suicidal Ideation: A Population-Based, Propensity-Weighted Cohort Study. RMD Open 2024, 10, e004466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coluzzi, F.; Fornasari, D.; Pergolizzi, J.; Romualdi, P. From Acute to Chronic Pain: Tapentadol in the Progressive Stages of This Disease Entity. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 21, 1672–1683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Littlejohn, G.O.; Guymer, E.K.; Ngian, G.-S. Is There a Role for Opioids in the Treatment of Fibromyalgia? Pain Manag. 2016, 6, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.; Schweinhardt, P. Dysfunctional Neurotransmitter Systems in Fibromyalgia, Their Role in Central Stress Circuitry and Pharmacological Actions on These Systems. Pain Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 741746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moret, C.; Briley, M. Antidepressants in the Treatment of Fibromyalgia. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2006, 2, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, L.M.; Choy, E.; Clauw, D.J.; Oka, H.; Whalen, E.; Semel, D.; Pauer, L.; Knapp, L. An Evidence-Based Review of Pregabalin for the Treatment of Fibromyalgia. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2018, 34, 1397–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, T.E.; Derry, S.; Wiffen, P.J.; Moore, R.A. Gabapentin for Fibromyalgia Pain in Adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017, CD012188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valera, E.; Ubhi, K.; Mante, M.; Rockenstein, E.; Masliah, E. Antidepressants Reduce Neuroinflammatory Responses and Astroglial Alpha-Synuclein Accumulation in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Multiple System Atrophy. Glia 2014, 62, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, M.R.; Loram, L.C.; Zhang, Y.; Shridhar, M.; Rezvani, N.; Berkelhammer, D.; Phipps, S.; Foster, P.S.; Landgraf, K.; Falke, J.J.; et al. Evidence That Tricyclic Small Molecules May Possess Toll-like Receptor and Myeloid Differentiation Protein 2 Activity. Neuroscience 2010, 168, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.-L.; Xu, B.; Li, S.-S.; Zhang, W.-S.; Xu, H.; Deng, X.-M.; Zhang, Y.-Q. Gabapentin Reduces CX3CL1 Signaling and Blocks Spinal Microglial Activation in Monoarthritic Rats. Mol. Brain 2012, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nürnberger, F.; Rummel, C.; Ott, D.; Gerstberger, R.; Schmidt, M.J.; Roth, J.; Leisengang, S. Gabapentinoids Suppress Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Interleukin-6 Production in Primary Cell Cultures of the Rat Spinal Dorsal Horn. Neuroimmunomodulation 2022, 30, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, P.; Hill, M.; Bogoda, N.; Subah, S.; Venkatesh, R. Palmitoylethanolamide: A Natural Compound for Health Management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| TSPO-Targeting RPs | Population | Main Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| [11C]PBR28 | 31 FM (29 females) 27 HCs (25 females) | FM patients exhibited the following: Widespread cortical elevations in TSPO binding (mainly in the medial and lateral walls of the frontal and parietal lobes). | [100] |

| [11C]PK11195 | 12 FM (5 females) 11 CRPS (3 females) 15 HCs (5 females) | FM patients exhibited the following:

| [101] |

| [18F]DPA-714 | 31 FM 18 HCs | FM patients exhibited the following:

| [102] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Coluzzi, F.; Zeboudj, L.; Scerpa, M.S.; Giorgio, A.; De Blasi, R.A.; Malcangio, M.; Rocco, M. Microglial Activation in Nociplastic Pain: From Preclinical Models to PET Neuroimaging and Implications for Targeted Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11861. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411861

Coluzzi F, Zeboudj L, Scerpa MS, Giorgio A, De Blasi RA, Malcangio M, Rocco M. Microglial Activation in Nociplastic Pain: From Preclinical Models to PET Neuroimaging and Implications for Targeted Therapeutic Strategies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11861. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411861

Chicago/Turabian StyleColuzzi, Flaminia, Lynda Zeboudj, Maria Sole Scerpa, Anna Giorgio, Roberto Alberto De Blasi, Marzia Malcangio, and Monica Rocco. 2025. "Microglial Activation in Nociplastic Pain: From Preclinical Models to PET Neuroimaging and Implications for Targeted Therapeutic Strategies" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11861. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411861

APA StyleColuzzi, F., Zeboudj, L., Scerpa, M. S., Giorgio, A., De Blasi, R. A., Malcangio, M., & Rocco, M. (2025). Microglial Activation in Nociplastic Pain: From Preclinical Models to PET Neuroimaging and Implications for Targeted Therapeutic Strategies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11861. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411861