Autoimmune Neuromuscular Disorders at a Molecular Crossroad: Linking Pathogenesis to Targeted Immunotherapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Disease Overviews and Integrated Immunopathogenesis

2.1. Myasthenia Gravis

2.1.1. Clinical Features and Subtypes

2.1.2. Immunopathogenesis

2.1.3. Crossroads Within MG

2.2. Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy (CIDP)

2.2.1. Clinical Features and Subtypes

2.2.2. Immunopathogenesis

2.2.3. Crossroads Within CIDP

2.3. Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies (IIM)

2.3.1. Dermatomyositis (DM)

Clinical Features and Subtypes

Immunopathogenesis

Crossroads Within DM

2.3.2. Polymyositis (PM)

Clinical Features and Subtypes

Immunopathogenesis

Crossroads Within PM

2.3.3. Immune-Mediated Necrotizing Myopathy (IMNM)

Clinical Features and Subtypes

Immunopathogenesis

Crossroads Within IMNM

2.3.4. Inclusion Body Myositis (IBM)

Clinical Features and Subtypes

Immunopathogenesis

Crossroads Within IBM

2.3.5. Antisynthetase Syndrome (ASyS)

Clinical Features and Subtypes

Immunopathogenesis

Crossroads Within ASyS

2.3.6. Overlap Myositis (OM)

Clinical Features and Subtypes

Immunopathogenesis

Crossroads Within OM

3. Molecular and Targeted Therapies

3.1. Myasthenia Gravis

- 1.

- Complement inhibitorsAs activation of the complement cascade is a key driver of pathology in AChR antibody-mediated MG and LRP4 MG, inhibiting the terminal pathway represents an evident therapeutic approach. Eculizumab, the first approved complement inhibitor (2017), remains a milestone therapy for refractory AChR-positive generalized MG. Ravulizumab, its long-acting successor, demonstrated compelling efficacy in the CHAMPION-MG Phase 3 trial and was FDA-approved in 2022. Zilucoplan, a subcutaneous macrocyclic peptide that blocks both C5 cleavage and C5b–C6 binding, showed rapid clinical benefit and gained approval in 2023 [64,67]. Additional candidates include gefurulimab, which inhibits hepatic complement synthesis, and the combination of pozelimab (anti-C5 antibody) with cemdisiran (a small interfering RNA that suppresses hepatic C5 production), currently in late-stage development [67]. Iptacopan, a factor B inhibitor of the alternative pathway, is also under evaluation, whereas vemircopan, a factor D inhibitor, was discontinued due to limited efficacy [67].

- 2.

- FcRn antagonistsThe neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) regulates immunoglobulin G (IgG) homeostasis. Inhibition of FcRn accelerates the degradation of IgG, thereby reducing both pathogenic and non-pathogenic antibodies. Efgartigimod, approved in 2021 following the Phase 3 ADAPT trial, was the first agent in this class to show marked IgG with significant clinical benefit in AChR-positive MG [67]. Rozanolixizumab received approval for both AChR-positive and MuSK-positive MG, demonstrating the broad applicability of FcRn blockade, which reduces IgG levels regardless of antigen specificity. This is particularly relevant in MuSK-MG, where IgG4 antibodies mediate disease independently of complement activation [67]. Nipocalomab, a next-generation aglycosylated monoclonal antibody, recently received FDA approval for generalized MG [68]. Batoclimab, a fully human IgG1 monoclonal antibody structurally modified to minimize cytotoxicity, is progressing through Phase 3 development. Across clinical studies, FcRn antagonists consistently achieve reductions exceeding 60% in total IgG within weeks, with corresponding clinical improvements in patients receiving immunotherapy [64]. Similar to complement inhibitors, these agents are expensive biologic therapies that necessitate repeated or prolonged administration to sustain IgG suppression and reduce both protective and pathogenic IgG. Clinical trials have reported infectious adverse events associated with their use. Consequently, these therapies are currently primarily reserved for patients exhibiting high disease activity or refractory myasthenia gravis [64,67,68].

- 3.

- B-cell and plasma-cell therapiesB cells and plasma cells contribute to the pathogenesis of myasthenia gravis by producing autoantibodies, making them important therapeutic targets. Rituximab, a chimeric mouse-human monoclonal antibody targeting the B cell surface antigen CD20, is utilized in refractory AChR-positive and MuSK-positive MG, with strong evidence supporting early intervention in MuSK-MG [64,67]. Additional B-cell-directed agents under active investigation include inebilizumab, a humanized anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody that broadly depletes CD19-expresing B cells, and mezagitamab, an anti-CD 38 monoclonal antibody targeting plasma cells, although efficacy has been modest. The B-cell activating factor (BAFF)/B-lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS) pathway is also a promising target. Belimumab, an anti-BAFF monoclonal antibody that inhibits B-cell proliferation and maturation, has demonstrated preliminary activity. Telitacicept, a fully human TACI-Fc fusion protein that neutralizes BAFF and BLyS, is in development for MG following its approval in systemic lupus erythematosus [67].

- 4.

- Other immunomodulatorsPro-inflammatory cytokines and T-B cell interactions contribute to the pathogenesis of myasthenia gravis; thus, interleukin-6 (IL-6) receptor represents a viable therapeutic strategy. Satralizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting the IL-6 receptor, is already approved for seropositive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) and is under investigation for MG. Tocilizumab, another IL-6 receptor blocker, is in Phase 2 trials for generalized MG, with preliminary reports indicating positive effects in refractory cases [67,69]. T-cell directed strategies include iscalimab, a monoclonal antibody against CD40 that disrupts co-stimulation between T and B cells [67]. Tacrolimus, a calcineurin inhibitor, serves as a steroid-sparing agent and may further benefit patients by stabilizing acetylcholine receptor clustering at the neuromuscular junction [70,71].

- 5.

- Cell-based and novel therapiesIn patients with myasthenia gravis who have persistent autoreactive B and T cells, cellular therapies such as chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell therapies targeting B-cell markers or autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation are designed to restore immune tolerance. A completed Phase 2b trial of Descartes-08, an autologous RNA-based CAR-T therapy targeting B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), is pending publication. Early data showed that repeated infusions without lymphodepleting chemotherapy were safe and well tolerated, with no dose-limiting toxicities, cytokine release syndrome, or neurotoxicity and only transient, mild adverse events [72]. Anti-CD19 CAR-T therapy, employing a DNA-based approach with lymphodepleting conditioning, has demonstrated promising outcomes in three reported refractory MG cases: one AChR-positive and two with concomitant Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS), achieving effective CD19-positive B-cell depletion and significant clinical improvement over two to six months of follow-up [73,74]. Together, these early data indicate that CAR-T-mediated depletion of pathogenic B cells and plasma cells can induce profound remission in highly refractory MG with an acceptable short-term safety profile in the reported series [72,73,74]. Another approach in development, MuSK-chimeric autoantibody receptor (CAAR-T) therapy, which uses chimeric autoantibody receptor T cells to selectively eliminate MuSK-specific B cells while sparing healthy B cells [67].Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (AHSCT) has been used in highly refractory MG, both AChR-positive or MuSK-positive MG, and even in seronegative patients. The majority of patients achieved complete remission or minimal manifestation status over a follow-up period of 1.5 to 10 years, often discontinuing all MG medications. A Phase 2 trial evaluating HSCT in MG is ongoing [65].

- 6.

- Surgical advancesThymectomy removes the site of autoantibody initiation in AChR-MG and can induce long-term remission, making it a cornerstone of treatment. Clinical trials demonstrated its superiority over conventional immunosuppression alone, with sustained benefit at five years [66]. Minimally invasive and robotic techniques now provide comparable remission rates with reduced morbidity compared to open surgery [75].

- 7.

- Special considerationsSex and age shape both the clinical presentation and prognosis of MG. Early-onset AChR-positive disease demonstrates a female predominance, while late-onset and thymoma-associated MG are more common in older men. Ocular presentations are particularly prevalent among elderly patients [64,76]. Currently, there is no targeted therapy specifically approved for ocular MG, and this subgroup is typically excluded from clinical trials of novel biologic agents. As a result, management primarily relies on symptomatic treatment and conventional immunotherapy, most often low-to-moderate dose corticosteroids with or without steroid-sparing agents. Observational studies indicate that early initiation of immunosuppression may reduce or delay secondary generalization in some cohorts; however, results are heterogenous and the quality of evidence remains limited. Consequently, this approach is based largely on expert consensus rather than high-level trial data [76]. Major randomized trials of complement inhibitors, FcRn antagonists and B-cell-directed agents in generalized myasthenia gravis have not identified significant sex-based differences in efficacy or safety. However, most studies lacked sufficient power for formal sex-stratified analyses.In seronegative MG, FcRn inhibitors may offer broad benefit regardless of antibody status, whereas complement inhibitors are unlikely to be helpful unless low-affinity AChR antibodies are present. Advanced assays can identify low-density AChR antibodies in some seronegative cases, who then respond similarly to seropositive patients. For truly seronegative disease, non-specific immunosuppression remains the mainstay, though biomarker-driven targeted therapy is a priority for future research [64,67,76].

3.2. CIDP

- 1.

- Complement inhibitorsComplement-mediated mechanisms contribute to demyelination in CIDP. Rilipubart (SAR445088), a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting C1s, is undergoing Phase 2 clinical evaluation in patients with inadequate response to, failure of, or no prior exposure to standard therapies [28]. Interim data indicate disease stabilization or improvement, along with benefits in fatigue, quality of life, and biomarker profiles [28,77]. Additional complement inhibitors under investigation include eculizumab and ravulizumab, which remain in active clinical trials, as well as zilucoplan and GL-2045, which have not yet progressed to clinical testing in CIDP [28].

- 2.

- FcRn antagonistsFcRn blockade, which demonstrated efficacy in myasthenia gravis, has recently emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy in CIDP. The pivotal Phase 3 ADHERE trial demonstrated that efgartigimod significantly reduced the risk of relapse compared to placebo, leading to FDA and EMA approval for the treatment of active CIDP following corticosteroid or immunoglobulin therapy. Similar to their application in myasthenia gravis, the use of FcRn antagonists in CIDP is limited by high cost, the requirement for chronic or repeated dosing to sustain IgG suppression, and the non-selective reduction in total IgG. Additionally, long-term safety data remain under investigation. Other FcRn antagonists, such as rozanolixizumab, nipocalimab, and batoclimab, are in late-phase clinical development, although current findings remain inconsistent [77].

- 3.

- B-cell-directed therapiesAlthough B-cells may not be the primary drivers of CIDP, their downstream signaling can amplify inflammatory injury, providing support for the rationale behind B-cell-directed therapies. Among these, anti-CD20 agents have shown promise in CIDP. Rituximab demonstrates efficacy in approximately 60% of patients with refractory disease, particularly in those with IgG4 antibodies to paranodal proteins such as CNTN1, Caspr1, or NF155. Randomized control trials in broader CIDP cohorts are ongoing. Ocrelizumab has also been studied, with case reports indicating prevention of further relapses and, in one case, near-complete resolution of electrophysiological abnormalities. The therapeutic potential of ofatumumab, a fully human anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, and ublituximab, a chimeric anti-CD20 antibody engineered for enhanced FcγRIII binding, remains to be fully determined. Relapse after anti-CD 20 therapy is hypothesized to be related to the persistence of antibody-producing cells, highlighting the need to target additional B-cell populations. These cells often express CD19 and CD38, making them attractive therapeutic targets. Daratumumab, a human monoclonal antibody targeting CD38, was initially developed for the treatment of multiple myeloma and represents a potential candidate, although there are currently no reports of its use in typical CIDP. Recent reviews indicate that B-cell-directed biologics are costly, are used off-label in CIDP, and are associated with risks including infusion reactions, hypogammaglobulinemia, and serious infections. Therefore, these agents are typically reserved for carefully selected patients who are refractory to standard treatments [28].Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) is essential for B-cell signaling and represents an attractive therapeutic target. BTK inhibitors are being investigated for their potential to reduce inflammation and demyelination in CIDP. Preliminary evidence indicates that these agents may be especially beneficial for patients with refractory disease [77].

- 4.

- Other immunomodulatorsProteasome inhibitors (PIs) target long-lived plasma cells that sustain autoantibody production and contribute to treatment resistance or relapse. In a case series of patients with refractory CIDP, bortezomib achieved disease stabilization and both clinical and electrophysiological improvement, sustained for up to one year with minimal systemic toxicity. However, neurotoxicity remains a significant limitation. Second-generation agents, such as carfilzomib and ixazomib, may offer more favorable safety profiles [28].T-cell-specific modulators have also been evaluated for their potential to modulate the T-cell component in CIDP. Fingolimod, a sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulator with established efficacy in multiple sclerosis, exhibits immunomodulatory effects by depleting naïve and central memory T cells, as well as reducing B memory cells. However, in the large Phase 3 FORCIDP trial involving patients in remission or standard therapy, fingolimod did not demonstrate significant benefit over placebo for the primary endpoint of time to confirmed worsening, nor for secondary or exploratory outcomes [78].

- 5.

- Cell-based and novel therapiesIn contrast to myasthenia gravis, next-generation CAR-T cell therapies have not yet been applied in CIDP. These approaches are under development to optimize costimulatory domains and improve efficacy while minimizing treatment-related complications. The lack of published reports likely reflects the substantial risks associated with the therapy, as well as the non-life-threatening nature of CIDP [28]. Conversely, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (AHSCT) has demonstrated potential for durable remission and functional recovery, although controlled trials comparing AHSCT with conventional or emerging therapies are lacking [28].

- 6.

- Special considerationsChronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) demonstrates a modest male predominance and occurs more frequently in individuals over 50 years of age, with both incidence and prevalence reaching their highest levels in older populations [4]. Age at onset significantly influences both the clinical phenotype and outcomes, as older patients generally experience greater axonal loss and a higher burden of comorbidities, which collectively diminish the likelihood of full recovery and narrow the safety margin for prolonged immunosuppressive therapy. However, most current studies lack sufficient power for sex-stratified analyses, and no consistent sex-specific differences in the efficacy or safety of IVIG, corticosteroids or newer targeted agents have been demonstrated [4,79].In antibody-mediated nodopathies such as anti-CNTN1 or anti-Caspr1, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is frequently ineffective. Rituximab has demonstrated promise in refractory cases; however, some patients fail to respond due to the persistence of long-lived plasma cells, anti-drug antibody formation, or the risk of hypogammaglobulinemia associated with repeated dosing. Emerging evidence suggests that mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) combined with corticosteroids has shown favorable outcomes in small series, though larger studies are needed to establish its role [80]. These therapeutic patterns highlight the importance of antibody identification in guiding treatment decisions. The failure of broad immunosuppressants such as fingolimod in clinical trials for CIDP demonstrates that empirical translation of therapies from other autoimmune diseases is unlikely to succeed unless age-related immune alterations, axonal pathology, and nodal or paranodal mechanisms are adequately addressed [28].

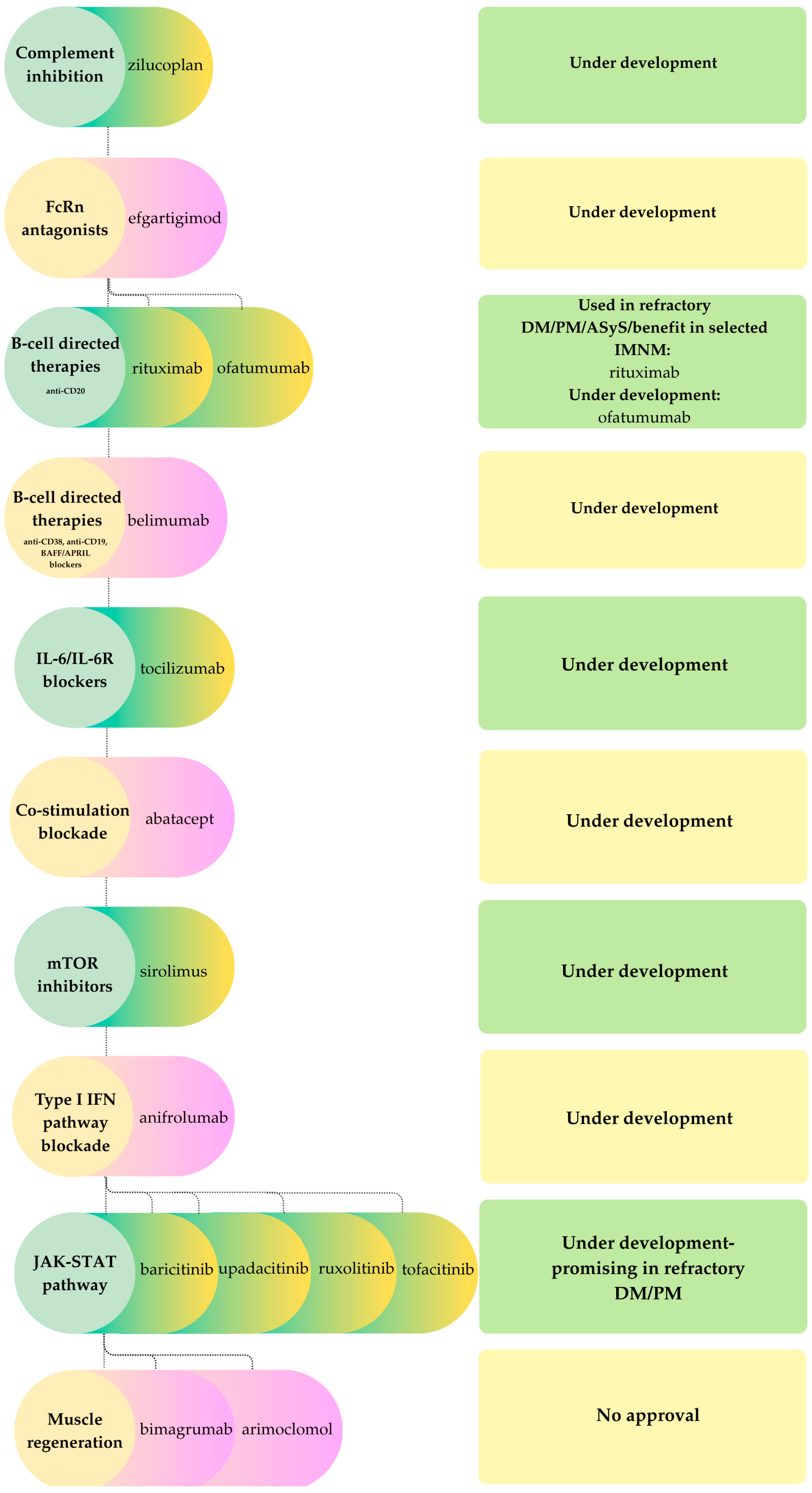

3.3. Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies

- 1.

- Complement inhibitorsComplement cascade activation contributes to muscle fiber injury in specific IIM subtypes, particularly immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM), where pathogenic antibodies (anti-HMGCR, anti-SRP) trigger complement deposition. Despite this, inhibition of the terminal pathway has not been demonstrated to be efficacious in established disease. For example, zilucoplan, a C5 inhibitor, did not improve muscle strength or function in a Phase II placebo-controlled trial. Likewise, in preclinical models, therapeutic C5 blockade after disease onset was ineffective in restoring muscle strength, whereas prophylactic administration prevented disease development. These observations indicate that complement activation in IIM may be a secondary effect rather than a primary pathogenic mechanism [82].

- 2.

- FcRn antagonistsGiven the proven pathogenic role of IgG autoantibodies in myositis, therapies targeting the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) have been explored. Efgartigimod has shown promise in immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM): in a recent case series involving refractory IMNM, efgartigimod produced rapid improvements in muscle strength within four weeks. The benefits persisted beyond a single treatment cycle [83], similar to sustained responses observed with FcRn blockade in myasthenia gravis. Although these findings are promising, questions remain regarding the durability of response, as repeated dosing may be necessary to maintain long-term remission. Controlled clinical trials of FcRn antagonists in IIM are required to establish efficacy [83].

- 3.

- B-cell targeted therapiesAutoantibody-producing B cells are central to many IIM subtypes, supporting the use of B-cell depletion strategies as a potential treatment option. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 26 studies including patients with dermatomyositis, polymyositis, antisynthetase syndrome, immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy and overlap myositis, but excluding sporadic inclusion body myositis, reported an overall rituximab response rate of about 65%. The efficacy estimate for antisynthetase syndrome was 62%. Severe adverse events and infections occurred in approximately 8% and 2% of patients, respectively. These findings indicate that rituximab is an effective and relatively safe treatment option for refractory, autoantibody-mediated IIM. However, randomized controlled trials are still needed to confirm these results [84]. In IMNM, rituximab and other B-cell directed agents, such as ofatumumab and belimumab, have shown clinical benefit in select treatment-resistant patients [83]. These results bring out the value of depleting B cells or neutralizing B-cell survival factors in autoantibody-mediated IIM. As previously noted in the context of CIDP, B-cell-directed biologics are expensive, predominantly used off-label, and carry risks including hypogammaglobulinemia and serious infections. Comparable considerations are relevant in IIM, where their administration is typically limited to carefully selected, refractory cases pending more comprehensive trial data and long-term safety outcomes.

- 4.

- Other immunomodulatorsJanus kinase (JAK) inhibitors represent a promising strategy for targeting cytokine signaling in IIM. Agents such as baricitinib, upadacitinib, ruxolitinib, and tofacitinib have demonstrated significant clinical improvements in refractory dermatomyositis (DM) and polymyositis (PM), especially in patients with prominent cutaneous involvement. A recent meta-analysis confirmed both the efficacy and safety of JAK-STAT pathway inhibition in DM and PM, supporting its broader application in myositis management [85].IL-6 inhibition. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a pro-inflammatory cytokine implicated in the pathogenesis of myositis. Tocilizumab, an anti-IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody, has shown benefit in both experimental and clinical settings. Two recent case reports described complete responses in anti-synthetase syndrome (ASyS) refractory to conventional therapies, including rituximab, with rapid normalization of muscle strength and systemic improvement. Although additional studies are necessary, these findings indicate that IL-6 inhibition may be a promising therapeutic option for refractory IIM, particularly in ASyS with systemic or articular involvement [86].IFN-pathway blockade. Type I interferon (IFN) pathway activation is a characteristic feature in dermatomyositis (DM), prompting evaluation of IFN pathway inhibition as a therapeutic strategy. Anifrolumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting the type I IFN receptor and approved in 2021 for systemic lupus erythematosus, has shown potential in refractory DM. Clinical reports indicate improved control of extramuscular disease, facilitation of glucocorticoid tapering, and reduction in the need for additional immunosuppressive therapy. These findings suggest that systemic IFN blockade may be effective for treatment-resistant DM with multi-organ involvement [87,88].Targeting T-cell costimulatory pathways represents another mechanistic approach in IIM. Abatacept, a CTLA-4-Ig fusion protein, inhibits T-cell co-stimulation and addresses dysregulated T-cell activity. It has been evaluated for its ability to reduce T-cell activation in myositis. Although initial reports suggested a benefit in refractory IIM, a 2021 randomized trial did not demonstrate a significant improvement in the overall study population. However, subgroup analyses revealed greater responsiveness in polymyositis (PM) and immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM) compared to dermatomyositis, suggesting the potential for selective therapeutic benefit [81].Inclusion body myositis (IBM) is characterized by prominent T-cell infiltration and muscle fiber degeneration. The mTOR inhibitor sirolimus (rapamycin) has been investigated for its ability to suppress effector T-cells and promote muscle autophagy. A Phase II trial conducted from 2015 to 2017 demonstrated that sirolimus slowed functional decline in IBM, although the observed benefits were modest. These findings prompted the initiation of a Phase III trial [89].

- 5.

- Cell-based and novel therapiesCellular therapies have been investigated in refractory polymyositis (PM) and dermatomyositis (DM), although clinical experience is limited. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (AHSCT) can induce remission by reconstituting the immune system, but carries substantial risks. Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) transplantation, which does not require myeloablation, has shown encouraging results in DM and PM, and has also led to anecdotal functional improvements in a small number of IBM cases, although clinical studies are scarce [90].CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell therapy has recently been studied in various IIM subtypes. Preliminary clinical experience indicates that this approach is generally well tolerated and may induce durable remission in select patients. A Phase I/II trial is currently evaluating CABA-201, a fully human anti- CD19 CAR-T cell product, in patients with refractory IIM. In an initial case of IMNM resistant to multiple immunosuppressants, CABA-201 was well tolerated, effectively depleted B cells, and reduced disease-associated autoantibodies without impairing pre-existing humoral immunity, highlighting the potential of this strategy [91]. In conjunction with previous MG studies, these findings indicate that CAR-T therapy can induce profound B-cell depletion and clinical remission in refractory MG and IMNM, with a more favorable safety profile than its use in oncology. However, long-term follow-up and studies involving larger cohorts remain necessary.

- 6.

- Special considerationsWithin the idiopathic inflammatory myopathy spectrum, sex and age distributions are heterogeneous and influence both clinical phenotype and therapeutic decision-making. Antibody-mediated forms such as dermatomyositis and immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy, typically exhibit a female predominance and most often present in mid- to late adulthood, with statin-associated IMNM occurring more frequently in older individuals [82,83,84]. In contrast, inclusion body myositis is primarily an age-restricted myopathy, usually manifesting after 50 years of age, with a higher frequency in men, and is notable for its resistance to conventional immunosuppressive therapies [89,92,93,94]. Age further impacts comorbidity burden, thereby reducing the safety margin for prolonged high-dose corticosteroid or intensive combination regimens. Although these epidemiological patterns are well established, clinical trials of the aforementioned therapeutic classes generally enroll insufficient numbers of patients to allow for robust sex- or age-stratified analyses, and no consistent differences in efficacy or safety between men and women have been demonstrated to date [82,83,84,85,86,95].Given the frequent lack of response to standard immunotherapies in IBM, muscle-targeted strategies have been explored as a potential approach. One such approach involves inhibiting myostatin, a member of the TGF-β family and a negative regulator of skeletal muscle mass. Bimagrumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody that blocks activin type 2 receptors and inhibits myostatin signaling, was found to be safe and increased muscle mass in clinical trials, but did not improve strength, mobility, or walking distance, even with extended treatment duration [92,93]. Another strategy to enhance muscle fiber proteostasis involves arimoclomol, an oral co-inducer of the heat shock response intended to improve protein clearance and reduce cellular stress. However, arimoclomol also failed to demonstrate meaningful clinical benefit. These results suggest that effective therapies for IBM may need to target multiple pathways simultaneously, including degeneration, inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and muscle atrophy [94].

| Drug Class/Mechanistic Target | MG | CIDP | IIM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shared across all three pathologies | |||

| Complement inhibitors | √ | √ | √ |

| FcRn antagonists | √ | √ | √ |

| B-cell directed therapies (anti-CD20) | √ | √ | √ |

| B-cell directed therapies (anti-CD19, anti-CD38, anti-BCMA, BAFF/APRIL blockers) | √ | √ | √ |

| Shared across two pathologies | |||

| IL-6/IL-6R blockers | √ | - | √ |

| Co-stimulation blockade | √ | - | √ |

| mTOR inhibitors | √ | - | √ |

| Conventional immunosuppressants | √ | - | √ |

| MG-specific | |||

| Thymectomy | √ | - | - |

| Calcineurin inhibitors | √ | - | - |

| CAR-T/CAAR-T therapies | √ | - | - |

| CIDP-specific | |||

| Proteasome inhibitors | - | √ | - |

| S1P receptor modulators | - | √ | - |

| IIM-specific | |||

| JAK-inhibitors | - | - | √ |

| Type-I-IFN blockade | - | - | √ |

| Muscle regeneration/proteostasis agents | - | - | √ |

| Cell-based therapies (AHSCT, MSC, CAR-T) | - | - | √ |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| AChR | acetylcholine receptor |

| ACR | American College of Rheumatology |

| ADAPT | Phase 3 trial of efgartigimod in MG |

| ADHERE | Phase 3 trial of efgartigimod in CIDP |

| AHSCT/HSCT | autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation/hematopoietic stem cell transplantation |

| AI | artificial intelligence |

| AIRE | autoimmune regulator |

| APRIL | A Proliferation-Inducing Ligand |

| APC | article processing charge |

| ASyS | antisynthetase syndrome |

| BAFF | B-cell activating factor |

| BCMA | B-cell maturation antigen |

| BLyS | B-lymphocyte stimulator |

| BTK | Bruton’s tyrosine kinase |

| CAAR-T | chimeric autoantibody receptor T-cell therapy |

| CAR-T | chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy |

| Caspr1 | contactin-associated protein-1 |

| CD | cluster of differentiation |

| CIDP | chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy |

| CISP | chronic immune sensory polyradiculopathy |

| CK | creatine kinase |

| CNTN1 | contactin-1 |

| CSF | cerebrospinal fluid |

| CTLA-4-Ig | cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein-4-IgG fusion protein |

| CXCL13/CCL21 | chemokines (thymic hyperplasia context) |

| DADS | distal acquired demyelinating symmetric neuropathy |

| DM | dermatomyositis |

| DMARDs (csDMARDs) | disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (conventional synthetic) |

| DTI | diffusion tensor imaging |

| EAN | experimental autoimmune neuritis |

| ECG | electrocardiogram |

| EMA/FDA | European Medicines Agency/U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| EMG | electromyography |

| EULAR | European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology |

| FcRIII | Fc gamma receptor III |

| FcRn | neonatal Fc receptor |

| FORCIDP | Phase 3 trial of fingolimod in CIDP |

| GC | glucocorticoids |

| GL-2045 | investigational complement-pathway agent |

| GRP78/BiP | glucose-regulated protein 78/binding immunoglobulin protein |

| HLA | human leukocyte antigen |

| HMGCR | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase |

| HSR | heat-shock response |

| IBM | inclusion body myositis |

| ICAM/VCAM | intercellular/vascular cell adhesion molecule |

| IFN/IFNAR | interferon/interferon-α/β receptor |

| IgG/IgM | immunoglobulin G/M |

| IIM | idiopathic inflammatory myopathies |

| IL-6/IL-6R | interleukin-6/interleukin-6 receptor |

| ILD | interstitial lung disease |

| IMNM | immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy |

| ISGs | interferon-stimulated genes |

| IVIG/SCIG | intravenous/subcutaneous immunoglobulin |

| JAK-STAT | Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| LEMS | Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome |

| LRP4 | low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 |

| MAC/TCC | membrane attack complex (C5b-9)/terminal complement complex |

| MADSAM | multifocal acquired demyelinating sensory and motor neuropathy (Lewis-Sumner) |

| MAG | myelin-associated glycoprotein |

| MGTX | randomized thymectomy trial in MG |

| MiRNA | microRNA |

| ML | machine learning |

| MMF | mycophenolate mofetil |

| MPZ/P0 | myelin protein zero |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| MuSK | muscle-specific tyrosine kinase |

| MxA | myxovirus resistance protein A |

| NCS | nerve conduction studies |

| NF/NF140/186/NF155/pan-NF | neurofascin isoforms and pan-neurofascin antibodies |

| NFEMG/SFEMG | near-fiber EMG/single-fiber EMG |

| NfL | neurofilament light chain |

| NMJ | neuromuscular junction |

| NMOSD | neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder |

| NOS2 | inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| OM | overlap myositis |

| PD-1/PD-L1/PD-L2 | programmed death-1 and ligands |

| PFA/PFN | perifascicular atrophy/perifascicular necrosis |

| PIs | proteasome inhibitors |

| PMP22 | peripheral myelin protein 22 |

| QoL | quality of life |

| S1P | sphingosine-1-phosphate (receptor) |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| SRP | signal recognition particle |

| TACI | transmembrane activator and CAML interactor |

| TCR | T-cell receptor |

| TDP-43 | TAR DNA-binding protein 43 |

| Tfh/Tfr | T-follicular helper/T-follicular regulatory cells |

| TGF-β | transforming growth factor-β |

| TIM-3 | T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 |

| TNF | tumor necrosis factor |

References

- Bidkar, P.U.; Satya Prakash, M.V.S. Neuromuscular Disorders. In Essentials of Neuroanesthesia; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 733–769. ISBN 978-0-12-805299-0. [Google Scholar]

- Shelly, S.; Mielke, M.M.; Paul, P.; Milone, M.; Tracy, J.A.; Mills, J.R.; Klein, C.J.; Ernste, F.C.; Mandrekar, J.; Liewluck, T. Incidence and prevalence of immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy in adults in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Muscle Nerve 2022, 65, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, M.; Martins, K.J.B.; Wong, K.O.; Vu, K.; Guigue, A.; Cohen Tervaert, J.W.; Gniadecki, R.; Klarenbach, S.W. Incidence and prevalence, and medication use among adults living with dermatomyositis: An Alberta, Canada population-based cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broers, M.C.; De Wilde, M.; Lingsma, H.F.; Van Der Lei, J.; Verhamme, K.M.C.; Jacobs, B.C. Epidemiology of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy in The Netherlands. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2022, 27, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Wilson, L.-A.; Arackal, J.; Edwards, Y.; Schwinn, J.; Rockstein, K.E.; Venker, B.; Nowak, R.J. Epidemiology and patient characteristics of the US myasthenia gravis population: Real-world evidence from a large insurance claims database. BMJ Neurol. Open 2025, 7, e001076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Cao, T.M.; Gelinas, D.; Griffin, R.; Mondou, E. Myasthenia gravis: Historical achievements and the “golden age” of clinical trials. J. Neurol. Sci. 2019, 406, 116428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminski, H.J.; Sikorski, P.; Coronel, S.I.; Kusner, L.L. Myasthenia gravis: The future is here. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e179742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, J.S.; Guptill, J.T.; Stathopoulos, P.; Nowak, R.J.; O’Connor, K.C. B cells in the pathophysiology of myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 2018, 57, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yixian, Z.; Hai, W.; Xiuying, L.; Jichun, Y. Advances in the genetics of myasthenia gravis: Insights from cutting-edge neuroscience research. Front. Med. 2025, 11, 1508422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witthayaweerasak, J.; Rattanalert, N.; Aui-aree, N. Prognostic factors for conversion to generalization in ocular myasthenia gravis. Medicine 2021, 100, e25899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Panse, R.; Berrih-Aknin, S. Immunopathogenesis of Myasthenia Gravis. In Myasthenia Gravis and Related Disorders; Kaminski, H.J., Kusner, L.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 47–60. ISBN 978-3-319-73584-9. [Google Scholar]

- Dresser, L.; Wlodarski, R.; Rezania, K.; Soliven, B. Myasthenia Gravis: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology and Clinical Manifestations. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti-Fine, B.M.; Milani, M.; Kaminski, H.J. Myasthenia gravis: Past, present, and future. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 2843–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michailidou, I.; Patsiarika, A.; Kesidou, E.; Boziki, M.K.; Parisis, D.; Bakirtzis, C.; Chroni, E.; Grigoriadis, N. The role of complement in the immunopathogenesis of acetylcholine receptor antibody-positive generalized myasthenia gravis: Bystander or key player? Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1526317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuquisana, O.; Stascheit, F.; Keller, C.W.; Pučić-Baković, M.; Patenaude, A.-M.; Lauc, G.; Tzartos, S.; Wiendl, H.; Willcox, N.; Meisel, A.; et al. Functional Signature of LRP4 Antibodies in Myasthenia Gravis. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2024, 11, e200220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Luo, J.; Garden, O.A. Immunoregulatory Cells in Myasthenia Gravis. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 593431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stathopoulos, P.; Kumar, A.; Heiden, J.A.V.; Pascual-Goñi, E.; Nowak, R.J.; O’Connor, K.C. Mechanisms underlying B cell immune dysregulation and autoantibody production in MuSK myasthenia gravis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2018, 1412, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridis, K.; Tzartos, S.J. Myasthenia Gravis: Autoantibody Specificities and Their Role in MG Management. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 596981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koike, H.; Nishi, R.; Ikeda, S.; Kawagashira, Y.; Iijima, M.; Katsuno, M.; Sobue, G. Ultrastructural mechanisms of macrophage-induced demyelination in CIDP. Neurology 2018, 91, 1051–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quint, P.; Schroeter, C.B.; Kohle, F.; Öztürk, M.; Meisel, A.; Tamburrino, G.; Mausberg, A.K.; Szepanowski, F.; Afzali, A.M.; Fischer, K.; et al. Preventing long-term disability in CIDP: The role of timely diagnosis and treatment monitoring in a multicenter CIDP cohort. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 5930–5943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doneddu, P.E.; Cocito, D.; Manganelli, F.; Fazio, R.; Briani, C.; Filosto, M.; Benedetti, L.; Mazzeo, A.; Marfia, G.A.; Cortese, A.; et al. Atypical CIDP: Diagnostic criteria, progression and treatment response. Data from the Italian CIDP Database. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2019, 90, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinot, V.; Rostasy, K.; Höftberger, R. Antibody-Mediated Nodo- and Paranodopathies. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Goñi, E.; Caballero-Ávila, M.; Querol, L. Antibodies in Autoimmune Neuropathies: What to Test, How to Test, Why to Test. Neurology 2024, 103, e209725, Erratum in: Neurology 2025, 104, e210298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appeltshauser, L.; Junghof, H.; Messinger, J.; Linke, J.; Haarmann, A.; Ayzenberg, I.; Baka, P.; Dorst, J.; Fisse, A.L.; Grüter, T.; et al. Anti-pan-neurofascin antibodies induce subclass-related complement activation and nodo-paranodal damage. Brain 2023, 146, 1932–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallat, J.; Mathis, S. Pathology explains various mechanisms of auto-immune inflammatory peripheral neuropathies. Brain Pathol. 2024, 34, e13184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Ávila, M.; Martin-Aguilar, L.; Collet-Vidiella, R.; Querol, L.; Pascual-Goñi, E. A pathophysiological and mechanistic review of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy therapy. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1575464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbert, J.; Cheng, M.I.; Horste, G.M.Z.; Su, M.A. Deciphering immune mechanisms in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathies. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e132411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, D.; Madi, H.; Eftimov, F.; Lunn, M.P.; Keddie, S. Novel therapies in CIDP. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2025, 96, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gable, K.L.; Li, Y. Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy: How Pathophysiology Can Guide Treatment. Muscle Nerve 2025, 72, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider-Hohendorf, T.; Schwab, N.; Üçeyler, N.; Göbel, K.; Sommer, C.; Wiendl, H. CD8+ T-cell immunity in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. Neurology 2012, 78, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclair, V.; Lundberg, I.E. New Myositis Classification Criteria—What We Have Learned Since Bohan and Peter. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2018, 20, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldroyd, A.; Chinoy, H. Recent developments in classification criteria and diagnosis guidelines for idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2018, 30, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Hu, X.; Wang, J.; Xu, Q.; Han, Z.; Zhou, H.; Gao, M. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis biomarkers. Clin. Chim. Acta 2023, 547, 117443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.M.S.; Campos, E.D.; Zanoteli, E. Inflammatory myopathies: An update for neurologists. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2022, 80, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; On, A.; Xing, E.; Shen, C.; Werth, V.P. Dermatomyositis: Focus on cutaneous features, etiopathogenetic mechanisms and their implications for treatment. Semin. Immunopathol. 2025, 47, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, M.; Shimizu, F.; Sato, R.; Nakamori, M. Contribution of Complement, Microangiopathy and Inflammation in Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2024, 11, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammen, A.L.; Allenbach, Y.; Stenzel, W.; Benveniste, O.; Allenbach, Y.; Benveniste, O.; Bleecker, J.D.; Boyer, O.; Casciola-Rosen, L.; Christopher-Stine, L.; et al. 239th ENMC International Workshop: Classification of dermatomyositis, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 14–16 December 2018. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2020, 30, 70–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyriou, A.; Horuluoglu, B.; Galindo-Feria, A.S.; Diaz-Boada, J.S.; Sijbranda, M.; Notarnicola, A.; Dani, L.; Van Vollenhoven, A.; Ramsköld, D.; Nennesmo, I.; et al. Single-cell profiling of muscle-infiltrating T cells in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. EMBO Mol. Med. 2023, 15, e17240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leclair, V.; Notarnicola, A.; Vencovsky, J.; Lundberg, I.E. Polymyositis: Does it really exist as a distinct clinical subset? Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2021, 33, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheeti, A.; Panginikkod, S. Dermatomyositis and Polymyositis. Available online: https://repository.escholarship.umassmed.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/2c9a663a-0801-4008-ad38-deec2573cb07/content (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Park, Y.-E.; Kim, D.-S.; Kang, M.; Shin, J.-H. Clinicopathological Reclassification of Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathy to Match the Serological Results of Myositis-Specific Antibodies. J. Clin. Neurol. 2024, 20, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalakas, M.C. Review: An update on inflammatory and autoimmune myopathies: Inflammatory myopathies. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2011, 37, 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtman, M.; Ekholm, L.; Hesselberg, E.; Chemin, K.; Malmström, V.; Reed, A.M.; Lundberg, I.E.; Padyukov, L. T-cell transcriptomics from peripheral blood highlights differences between polymyositis and dermatomyositis patients. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2018, 20, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allenbach, Y.; Benveniste, O.; Stenzel, W.; Boyer, O. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy: Clinical features and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendijk, J.E.; Amato, A.A.; Lecky, B.R.; Choy, E.H.; Lundberg, I.E.; Rose, M.R.; Vencovsky, J.; De Visser, M.; Hughes, R.A. 119th ENMC international workshop: Trial design in adult idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, with the exception of inclusion body myositis, 10–12 October 2003, Naarden, The Netherlands. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2004, 14, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weeding, E.; Tiniakou, E. Therapeutic Management of Immune-Mediated Necrotizing Myositis. Curr. Treat. Options Rheumatol. 2021, 7, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlonghi, G.; Antonini, G.; Garibaldi, M. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM): A myopathological challenge. Autoimmun. Rev. 2022, 21, 102993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S.; Nishikawa, A.; Kuwana, M.; Nishimura, H.; Watanabe, Y.; Nakahara, J.; Hayashi, Y.K.; Suzuki, N.; Nishino, I. Inflammatory myopathy with anti-signal recognition particle antibodies: Case series of 100 patients. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2015, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anquetil, C.; Boyer, O.; Wesner, N.; Benveniste, O.; Allenbach, Y. Myositis-specific autoantibodies, a cornerstone in immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy. Autoimmun. Rev. 2019, 18, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammen, A.L.; Chung, T.; Christopher-Stine, L.; Rosen, P.; Rosen, A.; Doering, K.R.; Casciola-Rosen, L.A. Autoantibodies against 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase in patients with statin-associated autoimmune myopathy. Arthritis Rheum. 2011, 63, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allenbach, Y.; Arouche-Delaperche, L.; Preusse, C.; Radbruch, H.; Butler-Browne, G.; Champtiaux, N.; Mariampillai, K.; Rigolet, A.; Hufnagl, P.; Zerbe, N.; et al. Necrosis in anti-SRP+ and anti-HMGCR+ myopathies: Role of autoantibodies and complement. Neurology 2018, 90, e507–e517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemin, V.; Butler-Browne, G.S.; Furling, D.; Mouly, V. IL-13 mediates the recruitment of reserve cells for fusion during IGF-1-induced hypertrophy of human myotubes. J. Cell Sci. 2007, 120, 670–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsley, V.; Jansen, K.M.; Mills, S.T.; Pavlath, G.K. IL-4 Acts as a Myoblast Recruitment Factor during Mammalian Muscle Growth. Cell 2003, 113, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arouche-Delaperche, L.; Allenbach, Y.; Amelin, D.; Preusse, C.; Mouly, V.; Mauhin, W.; Tchoupou, G.D.; Drouot, L.; Boyer, O.; Stenzel, W.; et al. Pathogenic role of anti–signal recognition protein and anti–3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl- C o A reductase antibodies in necrotizing myopathies: Myofiber atrophy and impairment of muscle regeneration in necrotizing autoimmune myopathies. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 81, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiniakou, E.; Girgis, A.; Safaei, T.N.; Albayda, J.; Adler, B.; Paik, J.J.; Mecoli, C.A.; Rebman, A.; Soloski, M.J.; Christopher-Stine, L.; et al. Precise identification and tracking of HMGCR-reactive CD4+ T cells in the target tissue of patients with anti-HMGCR immune-mediated necrotising myopathy. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2025, 84, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knauss, S.; Preusse, C.; Allenbach, Y.; Leonard-Louis, S.; Touat, M.; Fischer, N.; Radbruch, H.; Mothes, R.; Matyash, V.; Böhmerle, W.; et al. PD1 pathway in immune-mediated myopathies: Pathogenesis of dysfunctional T cells revisited. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 6, e558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llansó, L.; Segarra-Casas, A.; Domínguez-González, C.; Malfatti, E.; Kapetanovic, S.; Rodríguez-Santiago, B.; De La Calle, O.; Blanco, R.; Dobrescu, A.; Nascimento-Osorio, A.; et al. Absence of Pathogenic Mutations and Strong Association with HLA-DRB1*11:01 in Statin-Naïve Early-Onset Anti-HMGCR Necrotizing Myopathy. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2024, 11, e200285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hanlon, T.P.; Rider, L.G.; Mamyrova, G.; Targoff, I.N.; Arnett, F.C.; Reveille, J.D.; Carrington, M.; Gao, X.; Oddis, C.V.; Morel, P.A.; et al. HLA polymorphisms in African Americans with idiopathic inflammatory myopathy: Allelic profiles distinguish patients with different clinical phenotypes and myositis autoantibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54, 3670–3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnuki, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Shiina, T.; Uruha, A.; Watanabe, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Izumi, S.; Nakahara, J.; Hamanaka, K.; Takayama, K.; et al. HLA-DRB1 alleles in immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy. Neurology 2016, 87, 1954–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Bu, B.-T. Anti-SRP immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy: A critical review of current concepts. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1019972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, S.A. Inclusion body myositis: Clinical features and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2019, 15, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, C.; Li, H.; Bandyopadhyay, S. Coexistence of TDP-43 and C5b-9 staining of muscle in a patient with inclusion body myositis. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e238312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, D.Q.; Le, S.T.; Phan, K.H.P.; Doan, T.T.P.; Nguyen, L.N.K.; Dang, M.H.; Ly, T.T.; Phan, T.D.A. Immunohistochemical expression in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies at a single center in Vietnam. J. Pathol. Transl. Med. 2024, 58, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binks, S.N.M.; Morse, I.M.; Ashraghi, M.; Vincent, A.; Waters, P.; Leite, M.I. Myasthenia gravis in 2025: Five new things and four hopes for the future. J. Neurol. 2025, 272, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beland, B.; Storek, J.; Quartermain, L.; Hahn, C.; Pringle, C.E.; Bourque, P.R.; Kennah, M.; Kekre, N.; Bredeson, C.; Allan, D.; et al. Refractory myasthenia gravis treated with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2025, 12, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, G.I.; Kaminski, H.J.; Aban, I.B.; Minisman, G.; Kuo, H.-C.; Marx, A.; Ströbel, P.; Mazia, C.; Oger, J.; Cea, J.G.; et al. Long-term effect of thymectomy plus prednisone versus prednisone alone in patients with non-thymomatous myasthenia gravis: 2-year extension of the MGTX randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerischer, L.; Doksani, P.; Hoffmann, S.; Meisel, A. New and Emerging Biological Therapies for Myasthenia Gravis: A Focussed Review for Clinical Decision-Making. BioDrugs 2025, 39, 185–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrell, A. Efficacy and Safety of Nipocalimab in Patients with Generalised Myasthenia Gravis: Top Line Results from the Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomised Phase III Vivacity-MG3 Study. EMJ Neurol. 2024, 12, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Zhang, F.; Li, H.; Shen, Y.; Jin, Z.; Shi, F.-D.; Zhang, C. Responsiveness to Tocilizumab in Anti-Acetylcholine Receptor-Positive Generalized Myasthenia Gravis. Aging Dis. 2024, 15, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.L.; Wolff, M.L.; Vanderman, A.J.; Brown, J.N. The emerging role of tacrolimus in myasthenia gravis. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 2015, 8, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Li, Z.; Shen, F.; Zhang, X.; Lei, L.; Su, S.; Lu, Y.; Di, L.; Wang, M.; Xu, M.; et al. Favorable Effects of Tacrolimus Monotherapy on Myasthenia Gravis Patients. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 594152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granit, V.; Benatar, M.; Kurtoglu, M.; Miljković, M.D.; Chahin, N.; Sahagian, G.; Feinberg, M.H.; Slansky, A.; Vu, T.; Jewell, C.M.; et al. Safety and clinical activity of autologous RNA chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in myasthenia gravis (MG-001): A prospective, multicentre, open-label, non-randomised phase 1b/2a study. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 578–590, Correction in Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 578–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghikia, A.; Hegelmaier, T.; Wolleschak, D.; Böttcher, M.; Desel, C.; Borie, D.; Motte, J.; Schett, G.; Schroers, R.; Gold, R.; et al. Anti-CD19 CAR T cells for refractory myasthenia gravis. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 1104–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motte, J.; Sgodzai, M.; Schneider-Gold, C.; Steckel, N.; Mika, T.; Hegelmaier, T.; Borie, D.; Haghikia, A.; Mougiakakos, D.; Schroers, R.; et al. Treatment of concomitant myasthenia gravis and Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome with autologous CD19-targeted CAR T cells. Neuron 2024, 112, 1757–1763.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzmych, K.; Nachira, D.; Evoli, A.; Iorio, R.; Sassorossi, C.; Congedo, M.T.; Spagni, G.; Senatore, A.; Calabrese, G.; Margaritora, S.; et al. Surgical and Neurological Outcomes in Robotic Thymectomy for Myasthenic Patients with Thymoma. Life 2025, 15, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evoli, A.; Iorio, R. Controversies in Ocular Myasthenia Gravis. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 605902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabally, Y. Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathy: Current Therapeutic Approaches and Future Outlooks. ImmunoTargets Ther. 2024, 13, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.; Dalakas, M.C.; Merkies, I.; Latov, N.; Léger, J.-M.; Nobile-Orazio, E.; Sobue, G.; Genge, A.; Cornblath, D.; Merschhemke, M.; et al. Oral fingolimod for chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (FORCIDP Trial): A double-blind, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 689–698, Correction in Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, K.M.; Ousman, S.S. The immune response and aging in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. J. Neuroinflamm. 2021, 18, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Y.G.; Ju, W.; Sung, J.-J. Favorable long-term outcomes of autoimmune nodopathy with mycophenolate mofetil. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1515161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Lundberg, I.E.; Song, Y.; Shaibani, A.; Werth, V.P.; Maldonado, M.A. Efficacy and Safety of Subcutaneous Abatacept Plus Standard Treatment for Active Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathy: Phase 3 Randomized Controlled Trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2025, 77, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammen, A.L.; Amato, A.A.; Dimachkie, M.M.; Chinoy, H.; Hussain, Y.; Lilleker, J.B.; Pinal-Fernandez, I.; Allenbach, Y.; Boroojerdi, B.; Vanderkelen, M.; et al. Zilucoplan in immune-mediated necrotising myopathy: A phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023, 5, e67–e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Y.; Hao, H.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Zhao, Y. Treatment of refractory immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy with efgartigimod. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1447182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhen, C.; Hou, Y.; Zhao, B.; Ma, X.; Dai, T.; Yan, C. Efficacy and safety of rituximab treatment in patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1051609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Liu, M.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, K.; Wang, W. Therapeutic efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors in treating polymyositis/dermatomyositis: A single-arm systemic meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1382728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann Benvenuti, F.; Dudler, J. Long-lasting improvement of refractory antisynthetase syndrome with tocilizumab: A report of two cases. RMD Open 2023, 9, e003599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Jeurling, S.; Albayda, J.; Tiniakou, E.; Kang, J. Improvement of recalcitrant multisystem disease in dermatomyositis with anifrolumab: A case series. Rheumatology 2025, 64, 6354–6358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, P.S.; Ezenwa, E.; Ko, K.; Hoffman, M.D. Refractory dermatomyositis responsive to anifrolumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2024, 43, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benveniste, O.; Hogrel, J.-Y.; Belin, L.; Annoussamy, M.; Bachasson, D.; Rigolet, A.; Laforet, P.; Dzangué-Tchoupou, G.; Salem, J.-E.; Nguyen, L.S.; et al. Sirolimus for treatment of patients with inclusion body myositis: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, proof-of-concept, phase 2b trial. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021, 3, e40–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandolfi, S.; Pileyre, B.; Drouot, L.; Dubus, I.; Auquit-Auckbur, I.; Martinet, J. Stromal vascular fraction in the treatment of myositis. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkov, J.; Nunez, D.; Mozaffar, T.; Stadanlick, J.; Werner, M.; Vorndran, Z.; Ellis, A.; Williams, J.; Cicarelli, J.; Lam, Q.; et al. Case study of CD19 CAR T therapy in a subject with immune-mediate necrotizing myopathy treated in the RESET-Myositis phase I/II trial. Mol. Ther. 2024, 32, 3821–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, A.A.; Hanna, M.G.; Machado, P.M.; Badrising, U.A.; Chinoy, H.; Benveniste, O.; Karanam, A.K.; Wu, M.; Tankó, L.B.; Schubert-Tennigkeit, A.A.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Bimagrumab in Sporadic Inclusion Body Myositis: Long-term Extension of RESILIENT. Neurology 2021, 96, e1595–e1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, M.G.; Badrising, U.A.; Benveniste, O.; Lloyd, T.E.; Needham, M.; Chinoy, H.; Aoki, M.; Machado, P.M.; Liang, C.; Reardon, K.A.; et al. Safety and efficacy of intravenous bimagrumab in inclusion body myositis (RESILIENT): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 834–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, P.M.; McDermott, M.P.; Blaettler, T.; Sundgreen, C.; Amato, A.A.; Ciafaloni, E.; Freimer, M.; Gibson, S.B.; Jones, S.M.; Levine, T.D.; et al. Safety and efficacy of arimoclomol for inclusion body myositis: A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 900–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales-Selaya, C.; Prieto-Peña, D.; Martínez-López, D.; Benavides-Villanueva, F.; Blanco, R. Epidemiology of Dermatomyositis and Other Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies in Northern Spain. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, D.B.; Kouyoumdjian, J.A.; Stålberg, E.V. Single fiber electromyography and measuring jitter with concentric needle electrodes. Muscle Nerve 2022, 66, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandeville, R.; Patterson, A.; Luk, J.; Eleanore, A.; Garnés-Camarena, O.; Stashuk, D. Near Fiber Electromyography in the Diagnosis of Myasthenia Gravis: NFEMG in MG. RRNMF Neuromuscul. J. 2025, 6, 21795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozza, S.; Cassano, E.; Erra, C.; Muto, M.; Habetswallner, F.; Manganelli, F. Role of Imaging in Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Neurol. 2025, 32, e70226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Kong, X.; Alwalid, O.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Lu, Z.; Zheng, C. Multisequence Quantitative Magnetic Resonance Neurography of Brachial and Lumbosacral Plexus in Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 649071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, A.S.; Salam, S.; Dimachkie, M.M.; Machado, P.M.; Roy, B. Imaging biomarkers in the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1146015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelke, C.; Schroeter, C.B.; Barman, S.; Stascheit, F.; Masanneck, L.; Theissen, L.; Huntemann, N.; Walli, S.; Cengiz, D.; Dobelmann, V.; et al. Identification of disease phenotypes in acetylcholine receptor-antibody myasthenia gravis using proteomics-based consensus clustering. eBioMedicine 2024, 105, 105231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balistreri, C.R.; Vinciguerra, C.; Magro, D.; Di Stefano, V.; Monastero, R. Towards personalized management of myasthenia gravis phenotypes: From the role of multi-omics to the emerging biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Autoimmun. Rev. 2024, 23, 103669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, C.-C.; Wu, I.-C.; Bamodu, O.A.; Hong, C.-T.; Chiu, H.-C. Machine Learning in Myasthenia Gravis: A Systematic Review of Prognostic Models and AI-Assisted Clinical Assessments. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4418/15/16/2044 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Oeztuerk, M.; Henes, A.; Schroeter, C.B.; Nelke, C.; Quint, P.; Theissen, L.; Meuth, S.G.; Ruck, T. Current Biomarker Strategies in Autoimmune Neuromuscular Diseases. Cells 2023, 12, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamperman, R.G.; Veldkamp, S.R.; Evers, S.W.; Lim, J.; Van Schaik, I.; Van Royen-Kerkhof, A.; Van Wijk, F.; Van Der Kooi, A.J.; Jansen, M.; Raaphorst, J. Type I interferon biomarker in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: Associations of Siglec-1 with disease activity and treatment response. Rheumatology 2025, 64, 2979–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Xie, S.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Zuo, X.; Luo, H.; Zhu, H. Multiomics analysis uncovers subtype-specific mechanisms and biomarkers in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2025, 84, S0003496725043109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer Zu Hörste, G.; Gross, C.C.; Klotz, L.; Schwab, N.; Wiendl, H. Next-Generation Neuroimmunology: New Technologies to Understand Central Nervous System Autoimmunity. Trends Immunol. 2020, 41, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heming, M.; Börsch, A.-L.; Wolbert, J.; Thomas, C.; Mausberg, A.K.; Szepanowski, F.; Eggert, B.; Lu, I.-N.; Tietz, J.; Dienhart, F.; et al. Multi-omic identification of perineurial hyperplasia and lipid-associated nerve macrophages in human polyneuropathies. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syntakas, A.E.; Kartawinata, M.; Evans, N.M.L.; Nguyen, H.D.; Papadopoulou, C.; Obaidi, M.A.; Pilkington, C.; Glackin, Y.; Mahony, C.B.; Croft, A.P.; et al. Spatial transcriptomic analysis of muscle biopsy from patients with treatment-naive juvenile dermatomyositis reveals mitochondrial abnormalities despite disease-related interferon-driven signature. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2025, 84, 1706–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-C.; Liu, T.-C.; Lu, C.-J.; Chiu, H.-C.; Lin, W.-N. Machine learning strategy for identifying altered gut microbiomes for diagnostic screening in myasthenia gravis. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1227300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-C.; Yeh, J.-H.; Chiu, H.-C.; Chen, Y.-M.; Jhou, M.-J.; Liu, T.-C.; Lu, C.-J. Utilization of Decision Tree Algorithms for Supporting the Prediction of Intensive Care Unit Admission of Myasthenia Gravis: A Machine Learning-Based Approach. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballanti, S.; Liuzzi, P.; Mattiolo, P.L.; Scarpino, M.; Matà, S.; Hakiki, B.; Cecchi, F.; Oddo, C.M.; Mannini, A.; Grippo, A. Electrophysiological-based automatic subgroups diagnosis of patients with chronic dysimmune polyneuropathies. J. NeuroEng. Rehabil. 2025, 22, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Ro, L.; Lyu, R.; Kuo, H.; Liao, M.; Wu, Y.; Chen, C.; Chang, H.; Weng, Y.; Huang, C.; et al. Establishment of a new classification system for chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy based on unsupervised machine learning. Muscle Nerve 2022, 66, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeish, E.; Slater, N.; Mastaglia, F.L.; Needham, M.; Coudert, J.D. From data to diagnosis: How machine learning is revolutionizing biomarker discovery in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Brief. Bioinform. 2023, 25, bbad514, Correction in Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbad514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danieli, M.G.; Paladini, A.; Longhi, E.; Tonacci, A.; Gangemi, S. A machine learning analysis to evaluate the outcome measures in inflammatory myopathies. Autoimmun. Rev. 2023, 22, 103353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Target of Autoantibodies | Predominant IgG Subclasses | Complement Activation | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| AChR | IgG1, IgG3 | Yes Classical pathway (C1q → C3b/C4b, C3a/C5a, MAC) | Postsynaptic injury, loss of folds, reduced functional AChRs |

| MuSK | IgG4 (becomes functionally monovalent via Fab-arm exchange) | No Complement-independent mechanism | Inhibits LRP4-MuSK-agrin signaling → disrupts AChR clustering |

| LRP4 | IgG1 or IgG2 | Can activate complement, but less effectively | Blocks agrin-LRP4-MuSK signaling; lower circulating complement fragments; often milder phenotype |

| Agrin | - | - | Less frequently implicated |

| Nodopathy | Target Antigens | Typical Onset | Key Clinical Features | Antibody Isotypes | Biomarkers/ Monitoring | Notable Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-CNTN1 | Contactin-1 (CNTN1) | Subacute | Predominant motor involvement, ataxia, cranial nerve deficits | IgG4, IgG3 | Titers decline with effective therapy; useful for monitoring/relapse prediction | May be associated with nephrotic syndrome |

| Anti-Caspr1 | Contactin-associated protein 1 (Caspr1) | Acute/subacute | Tetraparesis, sensory deficits, cranial neuropathies, ataxia, tremor; respiratory failure | IgG4, IgG3 | Titers decline with effective therapy; monitoring value | Can be severe; cranial/respiratory involvement |

| Anti-NF155 | Neurofascin-155 (paranodal) | Variable | Distal motor weakness, cerebellar-like tremor, ataxia | (often) IgG4 | Titers useful for disease monitoring; elevated CSF protein is common | HLA-DRB1*15 association |

| Anti-nodal neurofascin (NF140/186) | Neurofascin-140 and neurofascin-186 | Variable | Often severe; tetraplegia, dysautonomia, cranial nerve involvement, nephrotic syndrome, respiratory compromise | Not specified (IgG subclasses reported variably) | Antibody detection supports diagnosis; severity guides close follow-up | Targets nodal isoforms; severe autonomic/respiratory involvement |

| Anti-pan-neurofascin | Neurofascin-140, neurofascin 155, neurofascin-186 | Variable | Severe phenotypes similar to above; multi-system involvement | Not specified (often pathogenic) | Antibody levels for tracking; high vigilance needed | Interferes with node of Ranvier assembly (pathogenicity supported experimentally) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Florea, A.-M.; Luca, D.-G.; Davidescu, E.I.; Popescu, B.-O. Autoimmune Neuromuscular Disorders at a Molecular Crossroad: Linking Pathogenesis to Targeted Immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11736. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311736

Florea A-M, Luca D-G, Davidescu EI, Popescu B-O. Autoimmune Neuromuscular Disorders at a Molecular Crossroad: Linking Pathogenesis to Targeted Immunotherapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11736. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311736

Chicago/Turabian StyleFlorea, Anca-Maria, Dimela-Gabriela Luca, Eugenia Irene Davidescu, and Bogdan-Ovidiu Popescu. 2025. "Autoimmune Neuromuscular Disorders at a Molecular Crossroad: Linking Pathogenesis to Targeted Immunotherapy" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11736. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311736

APA StyleFlorea, A.-M., Luca, D.-G., Davidescu, E. I., & Popescu, B.-O. (2025). Autoimmune Neuromuscular Disorders at a Molecular Crossroad: Linking Pathogenesis to Targeted Immunotherapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11736. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311736