Functional Genetic Frontiers in Plant ABC Transporters: Avenues Toward Cadmium Management

Abstract

1. Cadmium in Plants and the Strategic Targeting of ABC Transporters

2. Functional Genetic Manipulation Focusing on ABC Transporters in Plant Models

3. Harnessing ABC Transporters for Cadmium Management in Crops

4. Functional Manipulation of ABC Transporters Toward Cadmium Phytoremediation

5. Cross-Kingdom Engineering: A Perspective on Leveraging ABC Transporters for Plant Cadmium Research

6. Advancing ABC Transporter Research for Strategic Cadmium Management in Plants

- Redundancy and Specificity: The possible redundancy within the ABC transporter superfamily means that manipulating a single gene may not always yield a strong phenotype due to compensatory mechanisms. Moreover, the broad substrate specificity of some ABC transporters requires careful consideration to avoid unintended effects on essential nutrient homeostasis or the accumulation of other undesirable compounds (Table 1).

- Tissue-Specific, Developmental Regulation, and Tissue-Specific Promoters for Spatial Control: Achieving precise control over Cd accumulation requires tissue-specific and developmentally regulated gene expression. For example, promoting Cd efflux from roots while simultaneously enhancing its sequestration in non-edible leaves, or limiting its transport into reproductive organs, demands sophisticated genetic engineering approaches. Within this context, an important aspect in the genetic manipulation of ABC transporters for Cd mitigation involves the use of tissue-specific promoters. They often align with the plant’s developmental stages and can be categorized according to target tissues, such as roots, stems, leaves, flowers, or seeds. By combining regulatory elements through synthetic biology, these promoters enable fine-tuned modulation of metabolic pathways and stress responses, offering versatile tools for improving plant performance and designing tailored genetic interventions [32]. As evidenced by current studies (Table 1), several genetic constructs have relied on constitutive promoters which drive ubiquitous gene expression across multiple plant organs. While effective for functional characterization, such expression pattern may eventually cause unintended pleiotropic effects, including altered growth, metabolic imbalances, or energy costs in non-target tissues. Thus, future studies might leverage tissue-specific promoters to achieve spatially precise expression of ABC transporters, thereby optimizing plant tolerance while minimizing unintended effects in non-target tissues and providing a refined strategy for targeted Cd detoxification.

- Multi-gene Engineering: A promising avenue for enhancing plant tolerance to multiple toxic elements lies in multigene engineering, combining ABC transporters with genes involved in relevant pathways. A compelling example of this approach was recently demonstrated in rice, where the co-overexpression of OsPCS1, OsABCC1, and OsHMA3 led to dramatic reductions in As and Cd concentrations in the grain, without any detrimental effects on plant growth, reproduction, or essential mineral nutrient content [19]. Furthermore, co-expression of AtMRP7 with AtPCS1 was shown to alleviate the Cd-hypersensitivity caused by AtPCS1 overexpression, as the AtMRP7/AtPCS1 double-transformants exhibit fewer Cd-induced necrotic lesions despite similar shoot Cd levels in tobacco. This indicates that AtMRP7 enhances detoxification, likely by promoting the removal of Cd or PC–Cd complexes from the cytosol, thereby restoring the balance required for effective Cd sequestration [13]. Thus, incorporating approaches in which broad-specificity ABC transporters are co-engineered with metal-related genes might maximize detoxification and accumulation efficiency in different plant systems. This further underscores the value of strategically designed multigene approaches to overcome potential limitations of single-gene manipulation—such as redundancy or limited substrate specificity—while minimizing pleiotropic effects.

- Complex Interactions: The interplay between ABC transporters and other metal homeostasis components needs further elucidation. Understanding these complex networks is crucial for designing more effective and ABC-targeted interventions.

- Structural and Holistic Functional Characterization: Several studies have functionally analyzed ABC transporters through in vitro assays, ectopic genetic manipulation, interspecific strategies, or heterologous expression systems in yeast and other model organisms (Table 1), providing valuable insight into their potential roles in Cd transport. However, these approaches remain largely indirect, leaving many mechanistic aspects unresolved, and understanding these proteins requires a holistic approach that integrates structural, biochemical, and physiological analyses. To truly elucidate transporter function, future research might move toward protein-level structural and biochemical analyses, focusing on substrate-binding dynamics, ATP hydrolysis mechanisms, and conformational transitions that define transport directionality. Integrating multiple strategies such as protein modeling, and site-directed mutagenesis with in planta functional assays, for instance, will be relevant to bridge current genetic knowledge with precise molecular understanding. Such studies will ultimately clarify how ABC transporter structure dictates function, providing a more robust foundation for rational engineering aimed at Cd detoxification in plants.

- Metabolic Fine-Tuning of ABC Transporters for Cd Mitigation and Quality Optimization: Recent insights into CsABCG11.2 have underscored the need to view Cd tolerance not merely as a detoxification mechanism but as a metabolic equilibrium involving amino acid and nitrogen fluxes [8]. Future studies might focus on the fine-tuning of strategic ABC transporters, such as modifying CsABCG11.2 activity or substrate affinity rather than relying solely on gene silencing. Integrating transporter function into breeding and metabolic engineering frameworks could enable the development of genotypes or cultivars with balanced metabolite profiles, improved nutrient efficiency, regulated nitrogen metabolism, and minimized Cd accumulation, while preserving agronomic performance and commercial quality.

- Multi-stress and Combined Stress Studies: While several ABC-related investigations have focused on single-metal or single-stress scenarios (Table 1), real-world environments often present multiple co-occurring stresses, such as combinations of heavy metals or other abiotic and biotic stressors. Understanding how ABC transporters respond under such combined conditions is critical for developing robust plant genotypes capable of coping with multifactorial stress environments. Future research might explore synergistic or antagonistic effects on transporter activity, metal sequestration, and overall plant physiology, potentially guiding multi-targeted genetic interventions in the research context covering ABC proteins and plant genetic engineering tools.

- Multi-omic Integration: Building on this framework, our laboratories have focused on integrating multi-omic approaches in plants to unravel the complex regulation and interactions of molecules, including ABC transporters, under Cd stress [1,33]. Further research regarding this research strategy through complementary genetic engineering strategies is highly relevant for functional validation and potential translational applications.

- Translational Research: In addition to the various aspects mentioned in the topics above in previous sections, we emphasize that translating promising laboratory findings from model plants (like Arabidopsis) to high-biomass crops (like poplar, Brassica species) and staple food crops (like rice and wheat) under field conditions is a significant aspect to be addressed. Factors such as genetic background, environmental variability, and complex soil chemistry must be thoroughly investigated. Several of these translational dimensions have already been integrated throughout the previous sections, including, for instance, aspects of pleiotropic and field-relevant physiological trade-offs, and the recognition of constraints associated with single-gene modifications. Moreover, Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 and Table 1 consolidate these points by highlighting laboratory procedures with potential agronomic performance, soil–metal interactions, and implications for potential deployment under realistic cultivation scenarios, thereby outlining a structured progression from mechanistic insights to practical application. Together, these research aspects establish a coherent framework for translating ABC transporter research into field-applicable strategies across multiple plant species and environmental conditions upon Cd exposure.

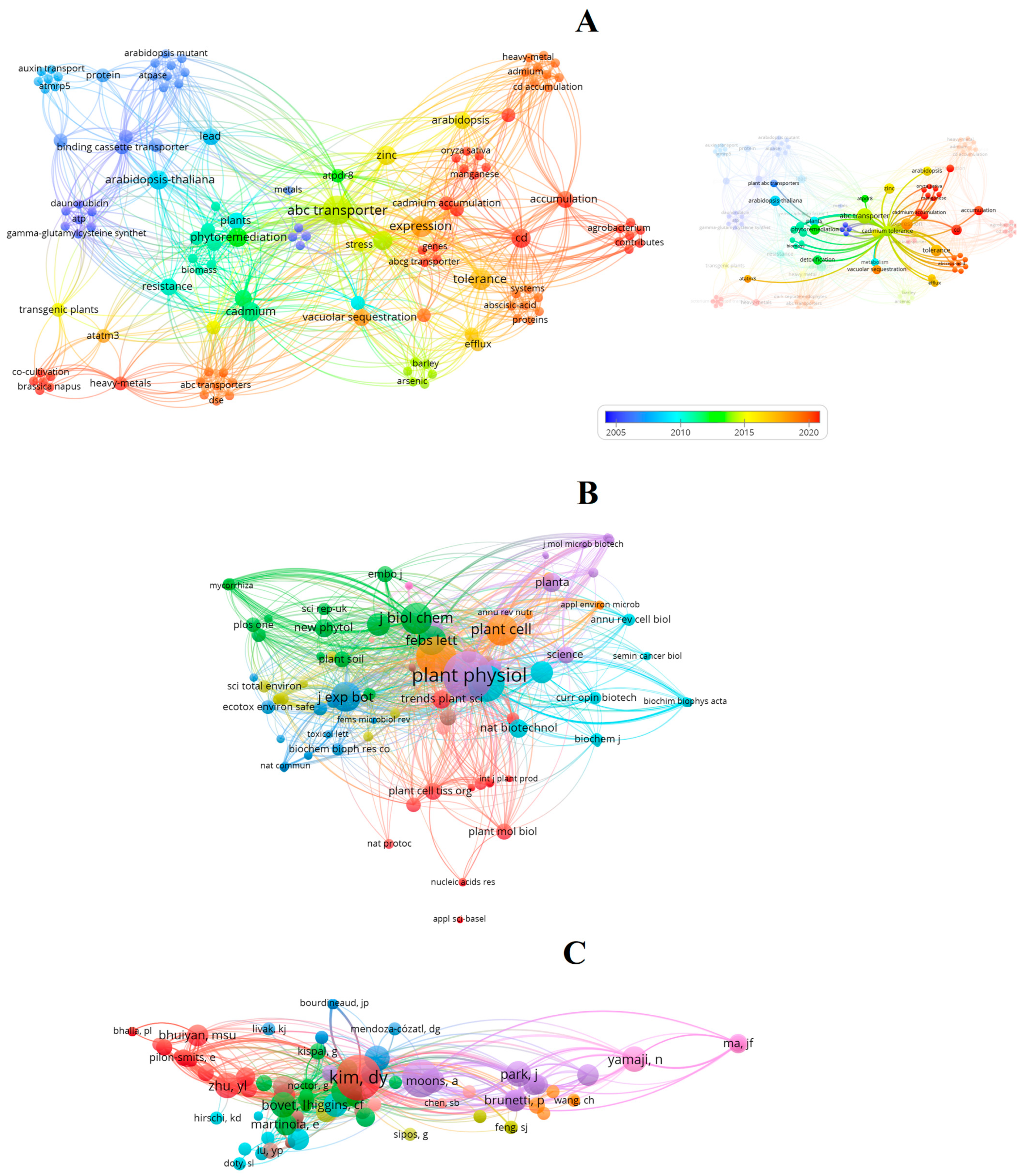

Bibliometric Analysis of Research Trends

7. Concluding Remarks and Additional Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marques, D.N.; Mason, C.; Stolze, S.C.; Harzen, A.; Nakagami, H.; Skirycz, A.; Piotto, F.A.; Azevedo, R.A. Grafting systems for plant cadmium research: Insights for basic plant physiology and applied mitigation. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; He, R.; Mu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Xing, W.; Liu, D. Cadmium toxicity in plants: From transport to tolerance mechanisms. Plant Signal. Behav. 2025, 20, 2544316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, D.N.; Thiengo, C.C.; Azevedo, R.A. Phytochelatins and cadmium mitigation: Harnessing genetic avenues for plant functional manipulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Wang, L.; Hui, S.; Yang, D.; He, Y.; Yuan, M. Cadmium accumulation regulated by a rice heavy-metal importer is harmful for host plant and leaf bacteria. J. Adv. Res. 2023, 45, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, S.S.; Lubna; Bilal, S.; Jan, R.; Asif, S.; Abdelbacki, A.M.M.; Kim, K.M.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Asaf, S. Exploring the role of ATP-binding cassette transporters in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) under cadmium stress through genome-wide and transcriptomic analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1536178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Yuan, X.; Li, L.; Zeng, M.; Yang, J.; Tang, H.; Duan, C. Genome-wide analysis of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family in Zea mays L. and its response to heavy metal stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, P.; Zanella, L.; De Paolis, A.; Di Litta, D.; Cecchetti, V.; Falasca, G.; Barbieri, M.; Altamura, M.M.; Costantino, P.; Cardarelli, M. Cadmium-inducible expression of the ABC-type transporter AtABCC3 increases phytochelatin-mediated cadmium tolerance in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 3815–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Xiahou, L.; Zhao, H.; Liu, J.; Guo, F.; Wang, P.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Ni, D.; Zhao, H. CsABCG11.2 mediates theanine uptake to alleviate cadmium toxicity in tea plants (Camellia sinensis). Hortic. Adv. 2024, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Z.; Man, J.; Wen, L.; Tan, S.Q.; Liu, S.L.; Li, Y.H.; Qi, P.F.; Jiang, Q.T.; Wei, Y.M. ATP-binding cassette transporter TaABCG2 contributes to Fusarium head blight resistance by mediating salicylic acid transport in wheat. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2024, 25, e70013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.Y.; Bovet, L.; Kushnir, S.; Noh, E.W.; Martinoia, E.; Lee, Y. AtATM3 is involved in heavy metal resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006, 140, 922–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Song, W.Y.; Ko, D.; Eom, Y.; Hansen, T.H.; Schiller, M.; Lee, T.G.; Martinoia, E.; Lee, Y. The phytochelatin transporters AtABCC1 and AtABCC2 mediate tolerance to cadmium and mercury. Plant J. 2012, 69, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Bovet, L.; Maeshima, M.; Martinoia, E.; Lee, Y. The ABC transporter AtPDR8 is a cadmium extrusion pump conferring heavy metal resistance. Plant J. 2007, 50, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojas, S.; Hennig, J.; Plaza, S.; Geisler, M.; Siemianowski, O.; Skłodowska, A.; Ruszczyńska, A.; Bulska, E.; Antosiewicz, D.M. Ectopic expression of Arabidopsis ABC transporter MRP7 modifies cadmium root-to-shoot transport and accumulation. Environ. Pollut. 2009, 157, 2781–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, S.; Jacquet, H.; Vavasseur, A.; Leonhardt, N.; Forestier, C. AtMRP6/AtABCC6, an ATP-binding cassette transporter gene expressed during early seedling development and up-regulated by cadmium in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2008, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Wang, M.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, C.; Ow, D.W. Overexpression of OsABCG48 lowers cadmium in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Agronomy 2021, 11, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, G.; Chao, D.; Wang, Z.; Shi, M.; Chen, J.; Chao, D.Y.; Li, R.; et al. The ABC transporter ABCG36 is required for cadmium tolerance in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 5909–5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Fu, S.; Huang, J.; Li, L.; Long, Y.; Wei, Q.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Xia, J. The tonoplast-localized transporter OsABCC9 is involved in cadmium tolerance and accumulation in rice. Plant Sci. 2021, 307, 110894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Li, C.; Sun, D.; Yang, Z.M. OsPDR20 is an ABCG metal transporter regulating cadmium accumulation in rice. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 136, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, Y.; Teo, J.; Tian, D.; Yin, Z. Genetic engineering low-arsenic and low-cadmium rice grain. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 2143–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.Y.; Yamaki, T.; Yamaji, N.; Ko, D.; Jung, K.H.; Fujii-Kashino, M.; An, G.; Martinoia, E.; Lee, Y.; Ma, J.F. A rice ABC transporter, OsABCC1, reduces arsenic accumulation in the grain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 15699–15704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhati, K.K.; Alok, A.; Kumar, A.; Kaur, J.; Tiwari, S.; Pandey, A.K. Silencing of ABCC13 transporter in wheat reveals its involvement in grain development, phytic acid accumulation and lateral root formation. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 4379–4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.S.U.; Min, S.R.; Jeong, W.J.; Sultana, S.; Choi, K.S.; Song, W.Y.; Lee, Y.; Lim, Y.P.; Liu, J.R. Overexpression of a yeast cadmium factor 1 (YCF1) enhances heavy metal tolerance and accumulation in Brassica juncea. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ Cult. 2011, 105, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.Y.; Choi, Y.I.; Shim, D.; Kim, D.Y.; Noh, E.W.; Martinoia, E.; Lee, Y. Transgenic poplar for phytoremediation. In Biotechnology and Sustainable Agriculture 2006 and Beyond; Xu, Z., Li, J., Xue, Y., Yang, W., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, D.; Kim, S.; Choi, Y.I.; Song, W.Y.; Park, J.; Youk, E.S.; Jeong, S.C.; Martinoia, E.; Noh, E.W.; Lee, Y. Transgenic poplar trees expressing yeast cadmium factor 1 exhibit the characteristics necessary for the phytoremediation of mine tailing soil. Chemosphere 2013, 90, 1478–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhuiyan, M.S.U.; Min, S.R.; Jeong, W.J.; Sultana, S.; Choi, K.S.; Lee, Y.; Liu, J.R. Overexpression of AtATM3 in Brassica juncea confers enhanced heavy metal tolerance and accumulation. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ Cult. 2011, 107, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, S.; Chakma, K.; Bhuiyan, M.S.U. Development of transgenic Brassica napus plants with AtATM3 gene to enhance cadmium and lead tolerance. J. Hortic. Sci. 2024, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Peng, Z.; Li, J.; Huang, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Xie, S.; Sun, L.; Han, E.; et al. Ectopic expression of poplar ABC transporter PtoABCG36 confers Cd tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazaki, K.; Yamanaka, N.; Masuno, T.; Konagai, S.; Shitan, N.; Kaneko, S.; Ueda, K.; Sato, F. Heterologous expression of a mammalian ABC transporter in plants and its application to phytoremediation. Plant Mol. Biol. 2006, 61, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Sohn, E.; Martinoia, E.; Lee, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jasinski, M.; Forestier, C.; Hwang, I.; Lee, Y. Engineering tolerance and accumulation of lead and cadmium in transgenic plants. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.H.; He, S.; Chen, D.; Li, T.; Zhao, Z.W. EpABC genes in the adaptive responses of Exophiala pisciphila to metal stress: Functional importance and relation to metal tolerance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e01844-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, G.; Liu, C.; Song, G.; Qian, J.; Bao, T.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, S.; Wan, D.; Mi, W.; He, M.; et al. Sll1725, an ABC transporter in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 for the detoxification of cadmium ion stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 300, 118389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Mo, Q.; Cai, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Zhou, D.; Yi, J. Promoters, key cis-regulatory elements, and their potential applications in regulation of cadmium (Cd) in rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, D.N.; Piotto, F.A.; Azevedo, R.A. Phosphoproteomics: Advances in research on cadmium-exposed plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Plant Species (Target of Genetic Manipulation) | ABC Transporter Genes/Proteins | Approaches (Genetic Manipulation) | Cd Exposure/Treatment Conditions | Examples of Observed Outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | AtABCC3 | Induced Overexpression (OE) (AtABCC3ox) using β-oestradiol | 30–90 μM CdSO4; 9 d exposure (seedlings); 10 μM β-oestradiol induction; leaf protoplasts analyzed. | Increased Cd tolerance; Increased vacuolar Cd sequestration and concomitant decrease in cytosolic Cd; Activity dependent on Phytochelatins (PCs). | [7] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | AtMRP6 (also known as AtABCC6) | Knockout (KO) (Transfer DNA (T-DNA) insertion, Atmrp6.1, Atmrp6.2) | 1–5 μM CdSO4; 21 d exposure; Seedlings analyzed. | Increased Cd sensitivity in seedlings; Significantly lower rosette-leaves Fresh weight (FW) in mutants compared to Wild-type (WT) after Cd treatment. | [14] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | AtATM3 | OE (35S::AtATM3) | 40 μM CdCl2 (2–3 wks, seedlings); 100 μM CdCl2 (24 h root treatment). | Enhanced Cd resistance (1.5–2-fold higher FW); Increased shoot Cd content; Resistance mechanism requires Glutathione (GSH). | [10] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | AtPDR8 | OE (35S::AtPDR8) | 40 μM CdCl2 (2–3 wks, seedlings); 0.1 μM 109CdCl2 (12 h uptake). | Enhanced Cd resistance (1.5–1.8-fold higher FW); Lower shoot and root Cd content; Higher Cd efflux rate (functions as a Plasma membrane (PM) extrusion pump). | [12] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | AtABCC1 | OE (35S::AtABCC1) | 40 or 60 μM CdCl2; 3 wks exposure (seedlings). | Enhanced Cd tolerance (higher shoot FW); Increased Cd accumulation in shoot, root, and total Cd content per plant. | [11] |

| Nicotiana tabacum var. Xanthi | AtMRP7 | OE (Heterologous expression under CaMV35S promoter) | 25 mM CdCl2 (6 d); 5 mM CdCl2 (3 d). | Increased Cd tolerance (higher shoot Dry matter (DM) yield); Increased Cd storage in leaf vacuoles (2–3-fold higher); Restricted Root-to-shoot concentration ratio (R/S) Cd translocation. AtMRP7 localized at PM and Tonoplast. | [13] |

| Triticum aestivum | TaABCC13 | RNA interference (RNAi) (Constitutive expression) | 50 μM CdCl2; 7 d exposure (seedlings). | Increased Cd sensitivity (significantly lower shoot biomass); Reduced Cd uptake in roots and shoots. | [21] |

| Oryza sativa | OsABCG48 (ABCG transporter) | OE; Transgenic expression (Agrobacterium) | 2 μM CdCl2 (5 d); 2 μM Cd (12 h after 28 d growth). | Enhanced Cd tolerance; Less root Cd accumulation than WT; Grew 3- to 4-fold more lateral roots under Cd stress. | [15] |

| Oryza sativa cv. Nipponbare | OsABCG36 | KO (CRISPR/Cas9, osabcg36-1, osabcg36-2) | 2 μM Cd (5 d seedlings); 5 μM CdSO4 (14 d); 20 μM Cd (8 h). | Enhanced Cd sensitivity (inhibited root growth); Increased root Cd concentration; Functions as a PM-localized efflux transporter. | [16] |

| Oryza sativa | OsABCC1 (Co-OE with OsPCS1, OsHMA3) | Co-OE (under OsActin1 promoter) | Paddy soil environment; Cd analyzed in grain. | Decreased Cd concentration in grain by 98% compared with non-transgenic control. | [19] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | CsABCG11.2 | OE (35S::CsABCG11.2) | 40 μM or 100 μM Cd (CdCl2); 2 wks plate/1 mo hydroponics; +/−20 μM Thea. | Increased Cd sensitivity (lethal dose); Enhanced Cd accumulation in shoots (76.5% translocation); Exogenous Thea mitigated toxicity. | [8] |

| Camellia sinensis | CsABCG11.2 | Knockdown (KD) (Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS), TRV-based) | 40 μM Cd (CdCl2) +/−50 μM Thea; 3 wks. | Reduced Cd accumulation in Young Leaves (YL); Confirmed role in Cd translocation from root to shoot. | [8] |

| Oryza sativa | OsPDR20 | RNAi/KD, KO (T-DNA) | Hydroponics: 2 or 10 μM Cd; 16 d. Field: 0.40 mg/kg Cd soil. | Increased Cd accumulation (1.91–2.97 folds in brown rice); Compromised growth/sensitivity; Suggests OsPDR20 functions to reduce Cd accumulation. | [18] |

| Oryza sativa | OsABCC1 | KO (T-DNA insertion) | Cd: Low/High conc. | No effect on Cd toxicity (Primary study focus was Arsenic (As)). | [20] |

| Oryza sativa | OsABCG43 | OE (Under maize Ubi promoter); KO (CRISPR/Cas9) | Hydroponics: 2.0, 5.0, or 30 μM CdCl2 (10–20 d); Field conditions. | Functions as a PM-localized Cd Importer. OE lines showed enhanced Cd accumulation (up to 3.0-fold in xylem sap); Resulted in Phytotoxicity and enhanced Cd sensitivity. | [4] |

| Oryza sativa (cv. Nipponbare) | OsABCC9 | KO (CRISPR/Cas9) | Hydroponics: 5 or 10 μM Cd (CdSO4); 12 d. Field: 2.0 mg/kg Cd soil. | KO lines exhibited enhanced Cd sensitivity (reduced root/shoot Dry weight (DW)); Accumulated more Cd; Sharply increased Cd concentration in grain (2–3 fold); Tonoplast-localized transporter mediating vacuolar sequestration of Cd. | [17] |

| Triticum turgidum subsp. durum | TaABCG2-5B | KO (TILLING/EMS, ΔTaabcg2-5B) | 2 mM Cd2+ (5 d). | ≈32% Decrease in Cd accumulation in root; Confirms function as a PM-localized Cd Importer. | [9] |

| Triticum turgidum subsp. durum | TaABCG2-5B | OE (UBI promoter, OE-TaABCG2-5B-16) | 2 mM Cd2+ (5 d). | ≈106% Increase in Cd accumulation in root; Confirms role as a PM-localized Cd Importer. | [9] |

| Brassica juncea | YCF1 | OE; Agrobacterium-based transformation | 0.15 M Cd(II) (CdCl2); 7 d (tolerance); 11 d (accumulation). | Enhanced Cd tolerance (1.3- to 1.6-fold higher FW than WT); Significantly increased accumulation of Cd(II) in shoot tissues. | [22] |

| Brassica juncea | AtATM3 | OE; Transgenic expression (Agrobacterium) | 0.15 M Cd(II) (CdCl2); 7 d (tolerance); 9–11 d (accumulation). | Enhanced Cd tolerance (2.2- to 2.3-fold higher FW than WT); Increased Cd accumulation in shoot; Upregulated BjGSHII and BjPCS1 transcripts. | [25] |

| Populus alba × P. tremula var. glandulosa (BH) | ScYCF1 | OE; Transgenic expression (Agrobacterium) | Tailing soil (43 mg kg−1 Cd) 2 wks; 1:1 Tailing soil 2 mos; Hydroponics: 1 ppm Cd, 4 wks. | Enhanced tolerance; Accumulated up to 5-fold more Cd in shoot than WT; Increased root system size; Increased accumulation of Cd, Zinc (Zn), and Lead (Pb) in root. | [24] |

| Brassica napus cv. BARI Sarisha-8 | AtATM3 | OE; Transgenic expression (Agrobacterium) | 0.15 M CdCl2 (7 d); 1/2 MS medium. | Enhanced Cd tolerance (1.4- to 1.7-fold higher FW than WT); Also showed increased Pb tolerance. | [26] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | PtoABCG36 (ABCG transporter) | OE; Transgenic expression (35S promoter) | 40 or 60 μM CdCl2 (2 wks); 100 μM CdCl2 (24 h, accumulation/Non-invasive micro-test (NMT)). | Enhanced Cd tolerance; Decreased Cd accumulation in shoot and root; Confirms function as a Cd extrusion pump (decreased net Cd2+ influx). | [27] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | EpABC2.1; EpABC3.1; EpABC4.1 (ABC transporters) | OE; Heterologous expression from E. pisciphila | 0, 0.1, or 1 μM Cd (20 d); 0, 0.2, or 0.4 mmol/kg Cd (25 d). | Enhanced Cd tolerance; Promoted Cd accumulation; Suggests detoxification via vacuolar compartmentalization. | [30] |

| Spirodela polyrhiza (Duckweed) | sll1725 (Type IV ABC transporter) | OE; Transgenic expression (UBI promoter; Agrobacterium) | 5 mg L−1 Cd2+; 5 d. | Enhanced Cd tolerance; Significantly higher Wet weight (WW) and DW than WT. | [31] |

| Nicotiana tabacum | hMRP1 (MRP subfamily of ABC transporter) | OE; Transgenic expression (Agrobacterium) | 0–100 μM CdCl2 (10 d, cultured cells); 0–480 μM Cd (14 d, seedlings). | Conferred clear resistance/tolerance to Cd (e.g., maintained chlorophyll content, greater FW/root length); hMRP1 localized at the vacuolar membrane. | [28] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Novaes Marques, D.; M. Mason, C. Functional Genetic Frontiers in Plant ABC Transporters: Avenues Toward Cadmium Management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11662. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311662

Novaes Marques D, M. Mason C. Functional Genetic Frontiers in Plant ABC Transporters: Avenues Toward Cadmium Management. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11662. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311662

Chicago/Turabian StyleNovaes Marques, Deyvid, and Chase M. Mason. 2025. "Functional Genetic Frontiers in Plant ABC Transporters: Avenues Toward Cadmium Management" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11662. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311662

APA StyleNovaes Marques, D., & M. Mason, C. (2025). Functional Genetic Frontiers in Plant ABC Transporters: Avenues Toward Cadmium Management. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11662. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311662