Quantifying the Activation Barrier for Phospholipid Monolayer Fusion Governing Lipid Droplet Coalescence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

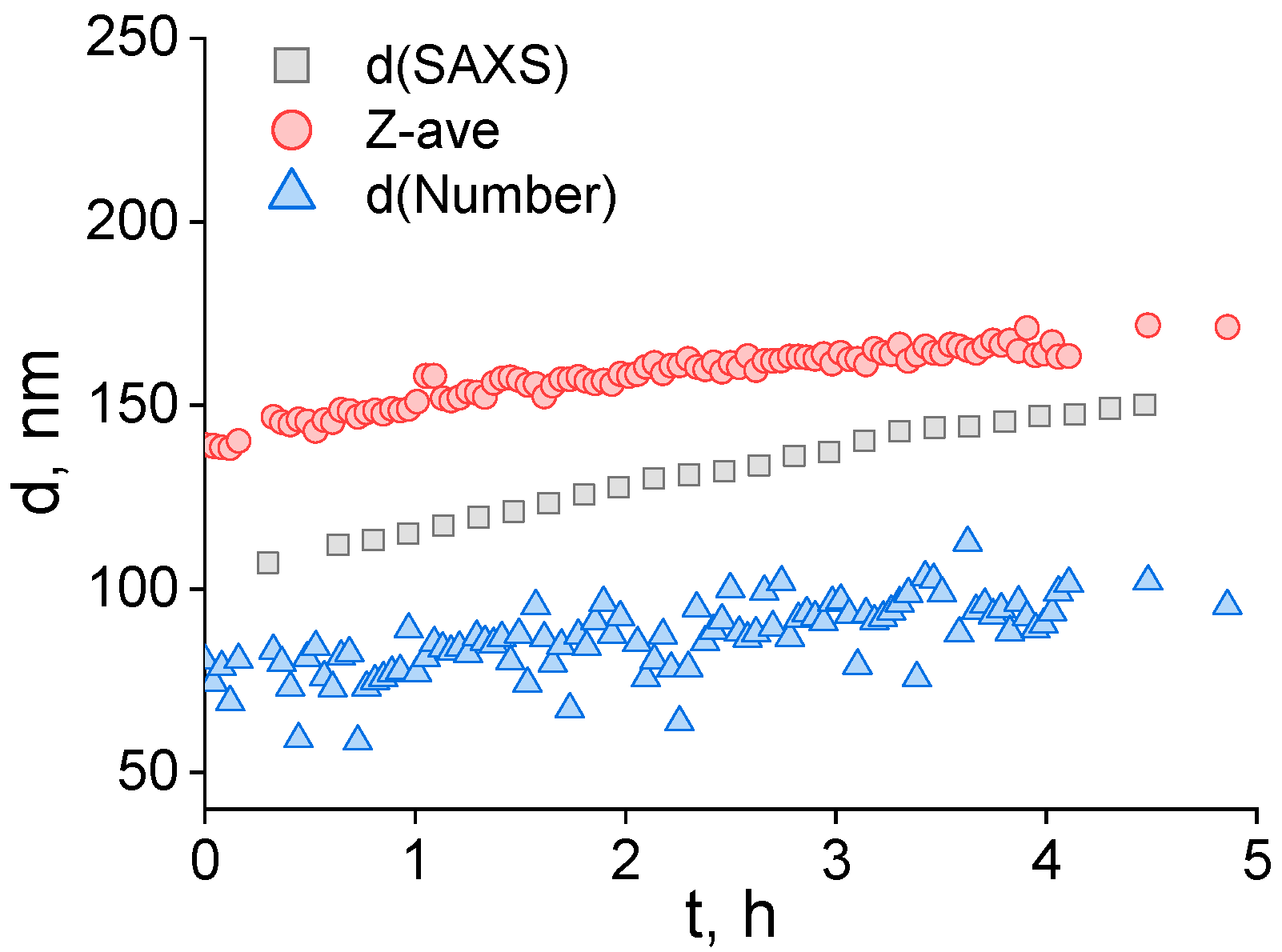

2.1. Colloidal Characteristics of Lipid Droplets

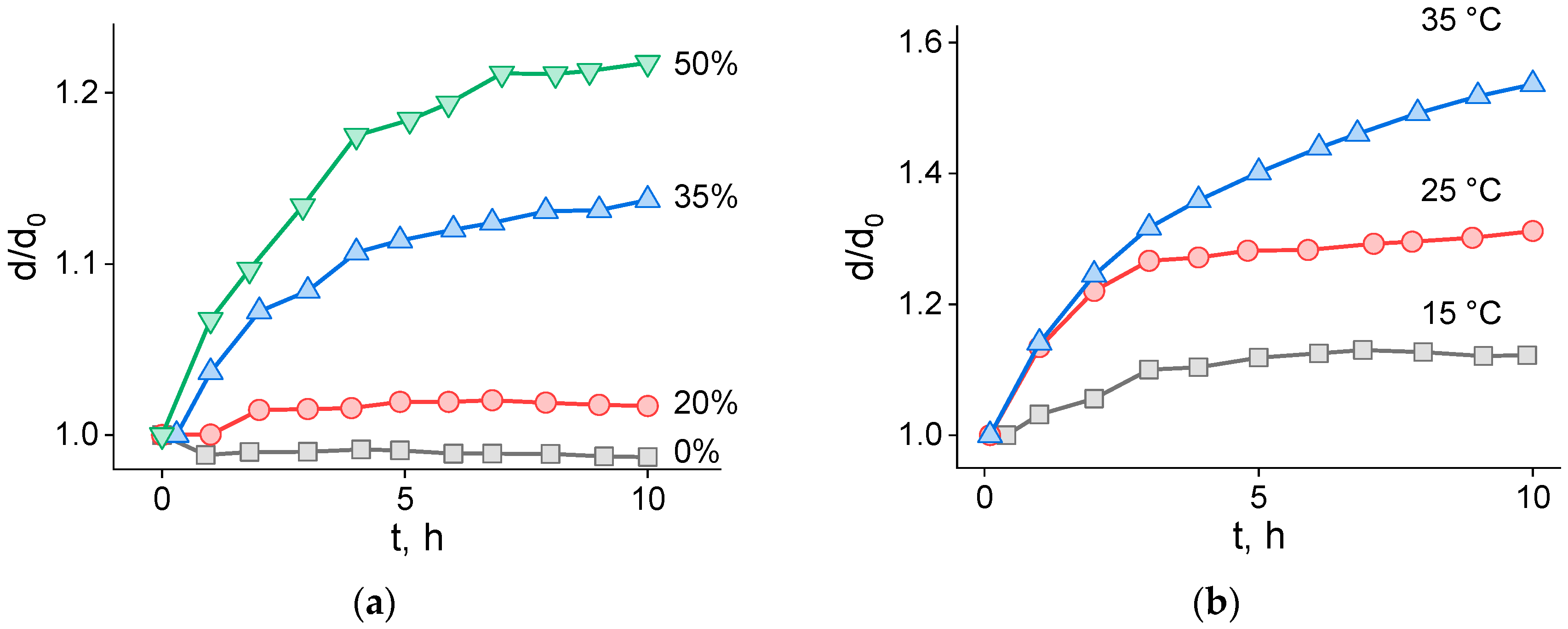

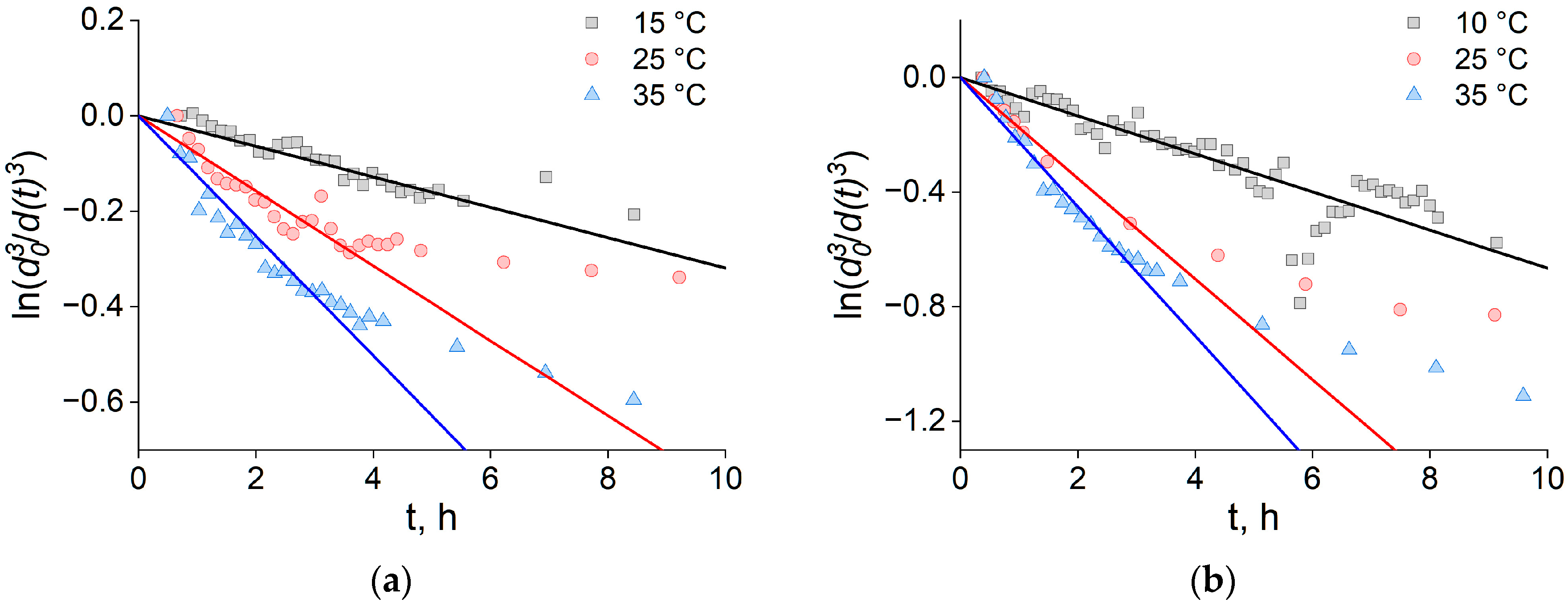

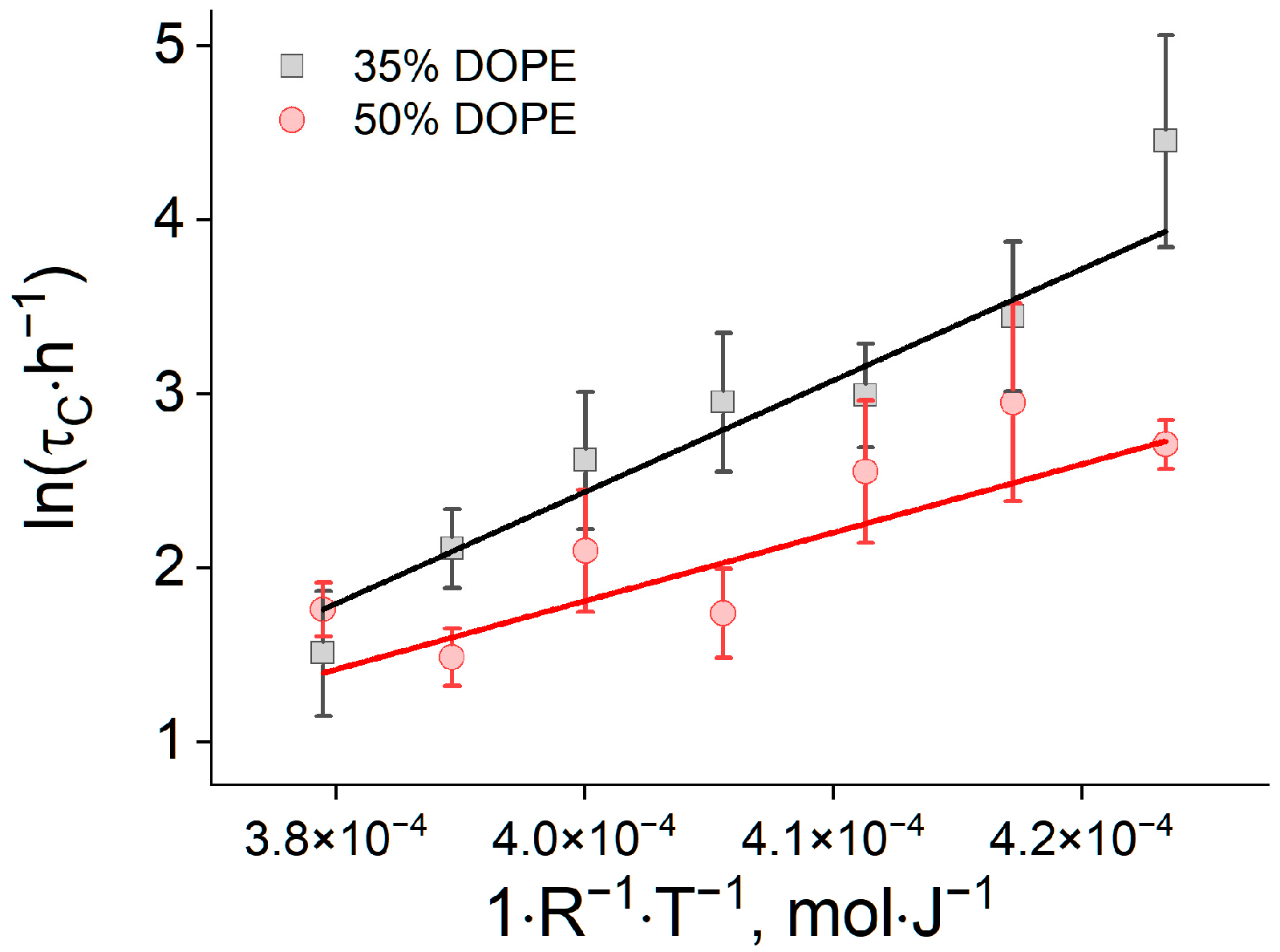

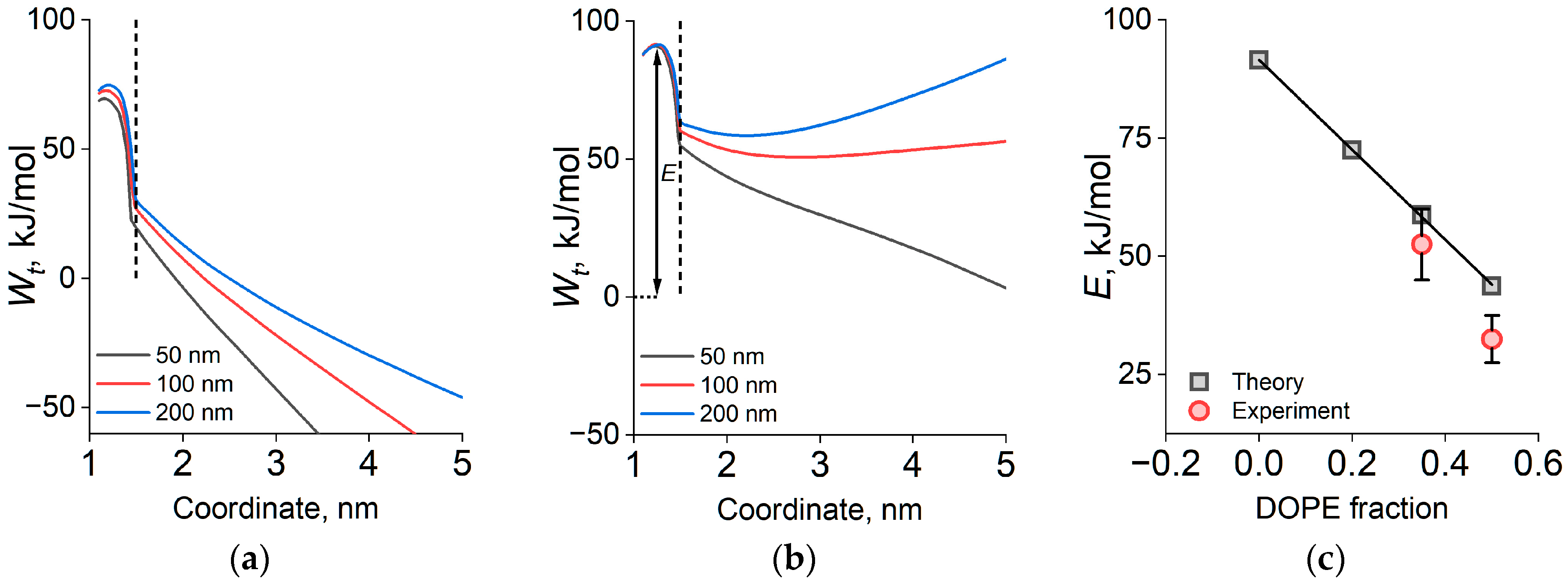

2.2. Coalescence Rate of Lipid Droplets and Coalescence Energy Barriers

2.3. Theoretical Modeling

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Preparation of Adiposome Emulsions

4.3. DLS Measurements

4.4. SAXS Measurements

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LD | Lipid droplet |

| DOPC | 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine |

| DOPE | 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylethanolamine |

| DLS | Dynamic light scattering |

| SAXS | Small-angle X-ray scattering |

| PdI | Polydispersity index |

| PE | Phosphatidylethanolamine |

References

- Tauchi-Sato, K.; Ozeki, S.; Houjou, T.; Taguchi, R.; Fujimoto, T. The Surface of Lipid Droplets Is a Phospholipid Monolayer with a Unique Fatty Acid Composition. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 44507–44512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiam, A.R.; Farese, R.V., Jr.; Walther, T.C. The Biophysics and Cell Biology of Lipid Droplets. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013, 14, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilfling, F.; Haas, J.T.; Walther, T.C.; Farese, R.V., Jr. Lipid Droplet Biogenesis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2014, 29, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olzmann, J.A.; Carvalho, P. Dynamics and Functions of Lipid Droplets. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, G.; Chen, F.-J.; Zhou, L.; Su, L.; Xu, D.; Xu, L.; Li, P. Control of Lipid Droplet Fusion and Growth by CIDE Family Proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2017, 1862, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, J.; Sun, Z.; Wu, L.; Xu, W.; Schieber, N.; Xu, D.; Shui, G.; Yang, H.; Parton, R.G.; Li, P. Fsp27 Promotes Lipid Droplet Growth by Lipid Exchange and Transfer at Lipid Droplet Contact Sites. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 195, 953–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.-C.; Raz, C.; Shamay, A.; Argov-Argaman, N. Lipid Droplet Fusion in Mammary Epithelial Cells Is Regulated by Phosphatidylethanolamine Metabolism. J. Mammary Gland. Biol. Neoplasia 2017, 22, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masedunskas, A.; Chen, Y.; Stussman, R.; Weigert, R.; Mather, I.H. Kinetics of Milk Lipid Droplet Transport, Growth, and Secretion Revealed by Intravital Imaging: Lipid Droplet Release Is Intermittently Stimulated by Oxytocin. MBoC 2017, 28, 935–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Galea, A.; Sytnyk, V.; Crossley, M. Controlling the Size of Lipid Droplets: Lipid and Protein Factors. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2012, 24, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.-C.; Shamay, A.; Argov-Argaman, N. Regulation of Lipid Droplet Size in Mammary Epithelial Cells by Remodeling of Membrane Lipid Composition—A Potential Mechanism. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluchowski, N.L.; Becuwe, M.; Walther, T.C.; Farese, R.V. Lipid Droplets and Liver Disease: From Basic Biology to Clinical Implications. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Wen, D.; Chen, G.; Chan, A.; Chen, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Han, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhu, J.; et al. Adipocyte-Derived Anticancer Lipid Droplets. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2100629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, P.; Zhao, Z.; Yu, Z.; Chen, L.; Jin, Y.; Wu, J.; Ren, Z. Application of Synthetic Lipid Droplets in Metabolic Diseases. Clin. Transl. Med. 2023, 13, e1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akimov, S.A.; Molotkovsky, R.J.; Kuzmin, P.I.; Galimzyanov, T.R.; Batishchev, O.V. Continuum Models of Membrane Fusion: Evolution of the Theory. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernomordik, L.V.; Kozlov, M.M. Mechanics of Membrane Fusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008, 15, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, R.V.; Akimov, S.A.; Dashinimaev, E.B.; Bashkirov, P.V. Boosting Lipofection Efficiency Through Enhanced Membrane Fusion Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlovsky, Y.; Kozlov, M.M. Stalk Model of Membrane Fusion: Solution of Energy Crisis. Biophys. J. 2002, 82, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryham, R.J.; Klotz, T.S.; Yao, L.; Cohen, F.S. Calculating Transition Energy Barriers and Characterizing Activation States for Steps of Fusion. Biophys. J. 2016, 110, 1110–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borwankar, R.P.; Lobo, L.A.; Wasan, D.T. Emulsion Stability—Kinetics of Flocculation and Coalescence. Colloids Surf. 1992, 69, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simovic, S.; Prestidge, C.A. Nanoparticles of Varying Hydrophobicity at the Emulsion Droplet−Water Interface: Adsorption and Coalescence Stability. Langmuir 2004, 20, 8357–8365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, H.-H.-Q.; Santanach-Carreras, E.; Lalanne-Aulet, M.; Schmitt, V.; Panizza, P.; Lequeux, F. Effect of a Surfactant Mixture on Coalescence Occurring in Concentrated Emulsions: The Hole Nucleation Theory Revisited. Langmuir 2021, 37, 8726–8737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabalnov, A.; Wennerström, H. Macroemulsion Stability: The Oriented Wedge Theory Revisited. Langmuir 1996, 12, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, H.; Kawagishi, A.; Tanaka, M.; Tanimoto, T.; Okada, S.; Komatsu, H.; Handa, T. Coalescence of Lipid Emulsions in Floating and Freeze–Thawing Processes: Examination of the Coalescence Transition State Theory. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 1999, 219, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molotkovsky, R.J.; Galimzyanov, T.R.; Minkevich, M.M.; Pinigin, K.V.; Kuzmin, P.I.; Bashkirov, P.V. Energy Pathway of Lipid Monolayer Fusion: From Droplet Contact to Coalescence. J. Phys. Chem. B 2025, 129, 7010–7021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.-M.; Ma, X.; Du, Y.; Zheng, L.; Liu, P. Construction of Nanodroplet/Adiposome and Artificial Lipid Droplets. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 3312–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P. Ostwald Ripening in Emulsions. Adv. Colloid. Interface Sci. 1998, 75, 107–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbina-Villalba, G.; Toro-Mendoza, J.; García-Sucre, M. Calculation of Flocculation and Coalescence Rates for Concentrated Dispersions Using Emulsion Stability Simulations. Langmuir 2005, 21, 1719–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leikin, S.L.; Kozlov, M.M.; Chernomordik, L.V.; Markin, V.S.; Chizmadzhev, Y.A. Membrane Fusion: Overcoming of the Hydration Barrier and Local Restructuring. J. Theor. Biol. 1987, 129, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmitzer, B.; Heftberger, P.; Rappolt, M.; Pabst, G. Monolayer Spontaneous Curvature of Raft-Forming Membrane Lipids. Soft Matter 2013, 9, 10877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashkirov, P.V.; Kuzmin, P.I.; Vera Lillo, J.; Frolov, V.A. Molecular Shape Solution for Mesoscopic Remodeling of Cellular Membranes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2022, 51, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niebergall, L.J.; Jacobs, R.L.; Chaba, T.; Vance, D.E. Phosphatidylcholine Protects against Steatosis in Mice but Not Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2011, 1811, 1177–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aeffner, S.; Reusch, T.; Weinhausen, B.; Salditt, T. Energetics of Stalk Intermediates in Membrane Fusion Are Controlled by Lipid Composition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E1609–E1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalutsky, M.A.; Galimzyanov, T.R.; Molotkovsky, R.J. A Model of Lipid Monolayer–Bilayer Fusion of Lipid Droplets and Peroxisomes. Membranes 2022, 12, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannette, C.; Baudry, J.; Chen, A.; Song, Y.; Shglabow, A.; Bremond, N.; Démoulin, D.; Walters, J.; Weitz, D.A.; Bibette, J. Thin Adhesive Oil Films Lead to Anomalously Stable Mixtures of Water in Oil. Science 2024, 384, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pays, K.; Giermanska-Kahn, J.; Pouligny, B.; Bibette, J.; Leal-Calderon, F. Coalescence in Surfactant-Stabilized Double Emulsions. Langmuir 2001, 17, 7758–7769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekvig, L.; Frenkel, D. Molecular Simulations of Droplet Coalescence in Oil/Water/Surfactant Systems. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 127, 134701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozlovsky, Y.; Efrat, A.; Siegel, D.A.; Kozlov, M.M. Stalk Phase Formation: Effects of Dehydration and Saddle Splay Modulus. Biophys. J. 2004, 87, 2508–2521, Correction in Biophys. J. 2008, 87, 3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattari, Z.; Köhler, S.; Xu, Y.; Aeffner, S.; Salditt, T. Stalk Formation as a Function of Lipid Composition Studied by X-Ray Reflectivity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Biomembr. 2015, 1848, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmin, P.I.; Zimmerberg, J.; Chizmadzhev, Y.A.; Cohen, F.S. A Quantitative Model for Membrane Fusion Based on Low-Energy Intermediates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 7235–7240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armarego, W.L.F. Purification of Laboratory Chemicals; Butterworth-Heinemann: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; ISBN 978-0-12-805457-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhi, Z.; Ma, X.; Zhou, C.; Mechler, A.; Zhang, S.; Liu, P. Protocol for Using Artificial Lipid Droplets to Study the Binding Affinity of Lipid Droplet-Associated Proteins. STAR Protoc. 2022, 3, 101214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, G.S.; Gaponov, Y.A.; Konarev, P.V.; Marchenkova, M.A.; Ilina, K.B.; Volkov, V.V.; Pisarevsky, Y.V.; Kovalchuk, M.V. Upgrade of the BioMUR Beamline at the Kurchatov Synchrotron Radiation Source for Serial Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering Experiments in Solutions. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2022, 1025, 166170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammersley, A.P. FIT2D: A Multi-Purpose Data Reduction, Analysis and Visualization Program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2016, 49, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konarev, P.V.; Volkov, V.V.; Sokolova, A.V.; Koch, M.H.J.; Svergun, D.I. PRIMUS: A Windows PC-Based System for Small-Angle Scattering Data Analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2003, 36, 1277–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinier, A. La Diffraction Des Rayons X Aux Très Petits Angles: Application à l’étude de Phénomènes Ultramicroscopiques. Ann. Phys. 1939, 11, 161–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manalastas-Cantos, K.; Konarev, P.V.; Hajizadeh, N.R.; Kikhney, A.G.; Petoukhov, M.V.; Molodenskiy, D.S.; Panjkovich, A.; Mertens, H.D.T.; Gruzinov, A.; Borges, C.; et al. ATSAS 3.0: Expanded Functionality and New Tools for Small-Angle Scattering Data Analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2021, 54, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfrich, W. Elastic Properties of Lipid Bilayers: Theory and Possible Experiments. Z. Für Naturforschung C 1973, 28, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israelachvili, J.; Pashley, R. The Hydrophobic Interaction Is Long Range, Decaying Exponentially with Distance. Nature 1982, 300, 341–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jülicher, F.; Seifert, U. Shape Equations for Axisymmetric Vesicles: A Clarification. Phys. Rev. E 1994, 49, 4728–4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rand, R.P.; Parsegian, V.A. Hydration Forces between Phospholipid Bilayers. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Rev. Biomembr. 1989, 988, 351–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawicz, W.; Olbrich, K.C.; McIntosh, T.; Needham, D.; Evans, E. Effect of Chain Length and Unsaturation on Elasticity of Lipid Bilayers. Biophys. J. 2000, 79, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Molar Ratio DOPC:DOPE | Hydrodynamic Diameter D, nm | PdI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number Mean | Intensity Mean | Z-Average | ||

| 100:0 | 62 ± 5 | 116 ± 22 | 94 ± 2 | 0.14 ± 0.01 |

| 80:20 | 69 ± 4 | 169 ± 43 | 111 ± 2 | 0.17 ± 0.01 |

| 65:35 | 61 ± 7 | 262 ± 42 | 122 ± 2 | 0.24 ± 0.01 |

| 50:50 | 69 ± 12 | 280 ± 58 | 153 ± 6 | 0.27 ± 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Molotkovsky, R.J.; Denieva, Z.G.; Senchikhin, I.N.; Urodkova, E.K.; Konarev, P.V.; Peters, G.S.; Galimzyanov, T.R.; Pavlov, R.V.; Bashkirov, P.V. Quantifying the Activation Barrier for Phospholipid Monolayer Fusion Governing Lipid Droplet Coalescence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11664. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311664

Molotkovsky RJ, Denieva ZG, Senchikhin IN, Urodkova EK, Konarev PV, Peters GS, Galimzyanov TR, Pavlov RV, Bashkirov PV. Quantifying the Activation Barrier for Phospholipid Monolayer Fusion Governing Lipid Droplet Coalescence. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11664. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311664

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolotkovsky, Rodion J., Zaret G. Denieva, Ivan N. Senchikhin, Ekaterina K. Urodkova, Petr V. Konarev, Georgy S. Peters, Timur R. Galimzyanov, Rais V. Pavlov, and Pavel V. Bashkirov. 2025. "Quantifying the Activation Barrier for Phospholipid Monolayer Fusion Governing Lipid Droplet Coalescence" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11664. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311664

APA StyleMolotkovsky, R. J., Denieva, Z. G., Senchikhin, I. N., Urodkova, E. K., Konarev, P. V., Peters, G. S., Galimzyanov, T. R., Pavlov, R. V., & Bashkirov, P. V. (2025). Quantifying the Activation Barrier for Phospholipid Monolayer Fusion Governing Lipid Droplet Coalescence. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11664. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311664