Do Food Preservatives Affect Staphylococcal Enterotoxin C Production Equally?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

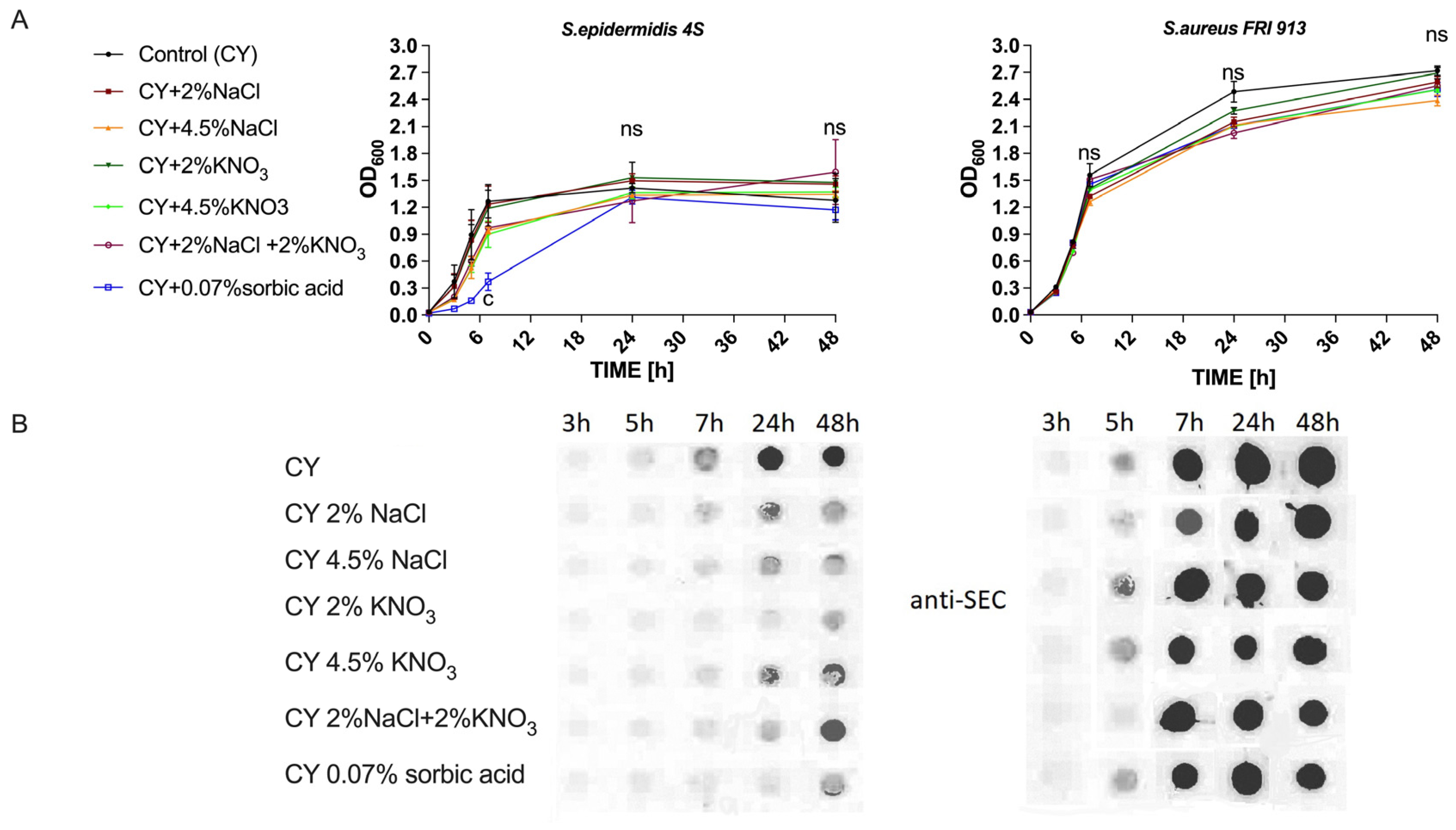

2.1. Growth and Determination of a Peak of Enterotoxin Production by S. epidermidis and S. aureus

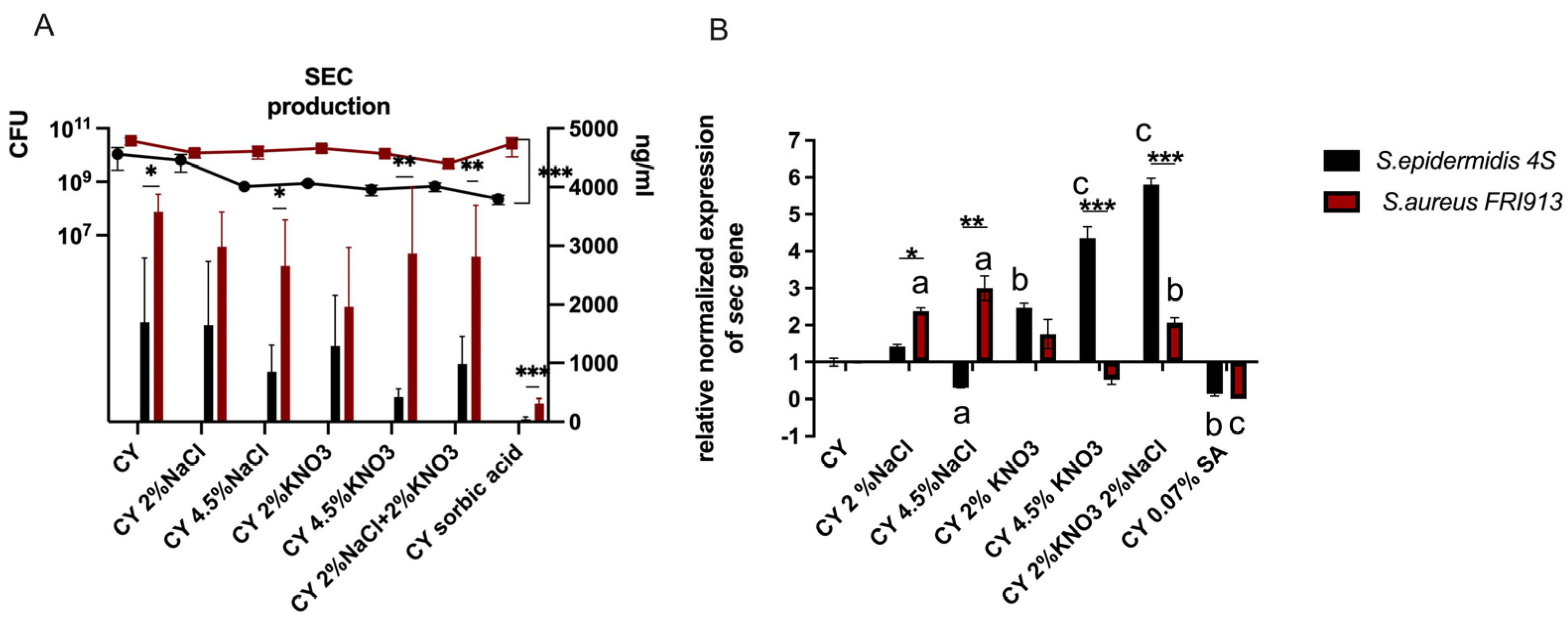

2.2. Effect of Food Preservatives on Secretion of SECepi and SEC3

2.3. Effect of Food Preservatives on mRNA Expression of Secepi and sec3

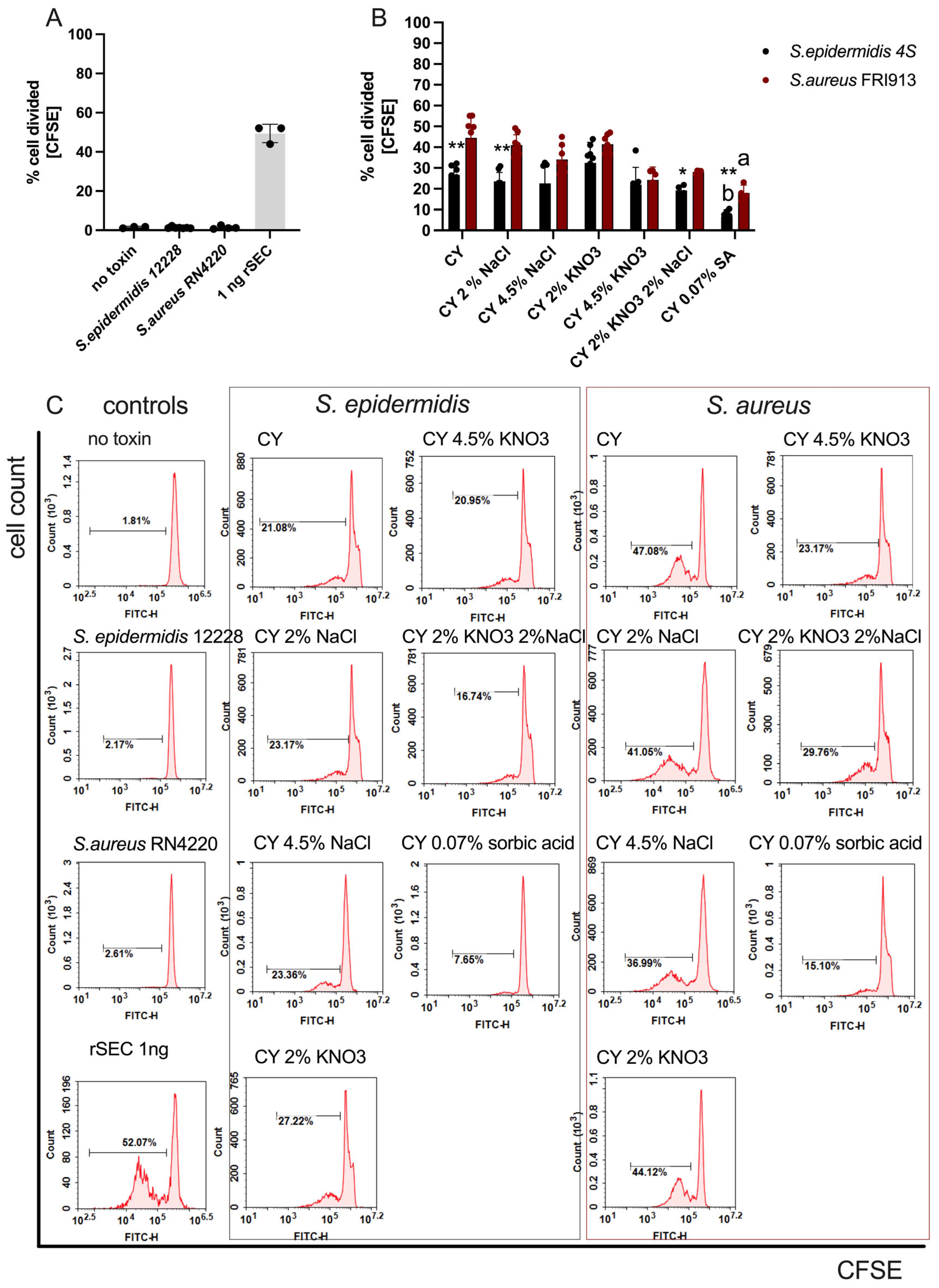

2.4. Proliferation Assay

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains and Growth Curve Determination

4.2. Dot Blot

4.3. Sandwich ELISA

4.4. RNA Extraction, Reverse Transcription, qPCR

4.5. PBMC Proliferation Assay

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); European Centre for Disease Prevention (ECDC). The European Union One Health 2023 Zoonoses Report. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e9106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scallan, E.; Hoekstra, R.M.; Angulo, F.J.; Tauxe, R.V.; Widdowson, M.A.; Roy, S.L.; Jones, J.L.; Griffin, P.M. Foodborne Illness Acquired in the United States-Major Pathogens. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeaki, N.; Rådström, P.; Schelin, J. Evaluation of Potential Effects of Nacl and Sorbic Acid on Staphylococcal Enterotoxin a Formation. Microorganisms 2015, 3, 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podkowik, M.; Park, J.Y.; Seo, K.S.; Bystroń, J.; Bania, J. Enterotoxigenic Potential of Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 163, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chajęcka-Wierzchowska, W.; Gajewska, J.; Wiśniewski, P.; Zadernowska, A. Enterotoxigenic Potential of Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci from Ready-to-Eat Food. Pathogens 2020, 9, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoli, C.E.; Njoga, E.O.; Enem, S.I.; Godwin, E.E.; Nwanta, J.A.; Chah, K.F. Prevalence, Toxigenic Potential and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profile of Staphylococcus Isolated from Ready-to-Eat Meats. Vet. World 2018, 11, 1214–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helak, I.; Daczkowska-Kozon, E.G.; Dłubała, A.A. Short Communication: Enterotoxigenic Potential of Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Isolated from Bovine Milk in Poland. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 3076–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Vermeulen, A.; Devlieghere, F. Modeling the Combined Effect of Temperature, PH, Acetic and Lactic Acid Concentrations on the Growth/No Growth Interface of Acid-Tolerant Bacillus Spores. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 360, 109419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihto, H.M.; Tasara, T.; Stephan, R.; Johler, S. Temporal Expression of the Staphylococcal Enterotoxin D Gene under NaCl Stress Conditions. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2015, 362, fnv024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewska, J.; Zakrzewski, A.J.; Chajęcka-Wierzchowska, W.; Zadernowska, A. Impact of the Food-Related Stress Conditions on the Expression of Enterotoxin Genes among Staphylococcus aureus. Pathogens 2023, 12, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelin, J.; Susilo, Y.B.; Johler, S. Expression of Staphylococcal Enterotoxins under Stress Encountered during Food Production and Preservation. Toxins 2017, 9, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihto, H.M.; Budi Susilo, Y.; Tasara, T.; Rådström, P.; Stephan, R.; Schelin, J.; Johler, S. Effect of Sodium Nitrite and Regulatory Mutations Δagr, ΔsarA, and ΔsigB on the MRNA and Protein Levels of Staphylococcal Enterotoxin D. Food Control 2016, 65, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robach, M.C.; Sofos, J.N. Use of Sorbates in Meat Products, Fresh Poultry and Poultry Products: A Review. J. Food Prot. 1982, 45, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofos, J.N.; Pierson, M.D.; Blocher, J.C.; Busta, F.F. Mode of Action of Sorbic Acid on Bacterial Cells and Spores. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1986, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Hu, J.Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, M.; Ou, J.; Yan, W.L. Assessment of the Inhibitory Effects of Sodium Nitrite, Nisin, Potassium Sorbate, and Sodium Lactate on Staphylococcus aureus Growth and Staphylococcal Enterotoxin A Production in Cooked Pork Sausage Using a Predictive Growth Model. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2018, 7, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieza, M.Y.R.; Bonsaglia, E.C.R.; Rall, V.L.M.; Santos, M.V.; dos Silva, N.C.C. Staphylococcal Enterotoxins: Description and Importance in Food. Pathogens 2024, 13, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argudín, M.Á.; Mendoza, M.C.; Rodicio, M.R. Food Poisoning and Staphylococcus aureus Enterotoxins. Toxins 2010, 2, 1751–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banaszkiewicz, S.; Wałecka-Zacharska, E.; Schubert, J.; Tabiś, A.; Król, J.; Stefaniak, T.; Węsierska, E.; Bania, J. Staphylococcal Enterotoxin Genes in Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci—Stability, Expression and Genomic Context. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabiś, A.; Gonet, M.; Schubert, J.; Miazek, A.; Nowak, M.; Tomaszek, A.; Bania, J. Analysis of Enterotoxigenic Effect of Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis Enterotoxins C and L on Mice. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 258, 126979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonet, M.; Krowarsch, D.; Schubert, J.; Tabiś, A.; Bania, J. Stability and Resistance to Proteolysis of Enterotoxins SEC and SEL Produced by Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2023, 20, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podkowik, M.; Seo, K.S.; Schubert, J.; Tolo, I.; Robinson, D.A.; Bania, J.; Bystroń, J. Genotype and Enterotoxigenicity of Staphylococcus epidermidis Isolate from Ready to Eat Meat Products. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 229, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurrahman, G.; Schmiedeke, F.; Bachert, C.; Bröker, B.M.; Holtfreter, S. Allergy—A New Role for T Cell Superantigens of Staphylococcus aureus? Toxins 2020, 12, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, T.; Korolkova, O.Y.; Rachakonda, G.; Williams, A.D.; Hawkins, A.T.; James, S.D.; Sakwe, A.M.; Hui, N.; Wang, L.; Yu, C.; et al. Linking Bacterial Enterotoxins and Alpha Defensin 5 Expansion in the Crohn’s Colitis: A New Insight into the Etiopathogenetic and Differentiation Triggers Driving Colonic Inflammatory Bowel Disease. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0304732, Erratum in PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, R.J. The Potential Role of Superantigens in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1995, 100, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.Y.; Fox, L.K.; Seo, K.S.; McGuire, M.A.; Park, Y.H.; Rurangirwa, F.R.; Sischo, W.M.; Bohach, G.A. Detection of Classical and Newly Described Staphylococcal Superantigen Genes in Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Isolated from Bovine Intramammary Infections. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 147, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zell, C.; Resch, M.; Rosenstein, R.; Albrecht, T.; Hertel, C.; Götz, F. Characterization of Toxin Production of Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Isolated from Food and Starter Cultures. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 127, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelin, J.; Wallin-Carlquist, N.; Cohn, M.T.; Lindqvist, R.; Barker, G.C.; Rådström, P. The Formation of Staphylococcus aureus Enterotoxin in Food Environments and Advances in Risk Assessment. Virulence 2011, 2, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, D.L.; Omoe, K.; Shimoda, Y.; Nakane, A.; Shinagawa, K. Induction of Emetic Response to Staphylococcal Enterotoxins in the House Musk Shrew (Suncus murinus). Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewska, J.; Zakrzewski, A.; Chajęcka-Wierzchowska, W.; Zadernowska, A. Meta-Analysis of the Global Occurrence of S. aureus in Raw Cattle Milk and Artisanal Cheeses. Food Control 2023, 147, 109603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regassa, L.B.; Couch, J.L.; Betley, M.J. Steady-State Staphylococcal Enterotoxin Type C mRNA Is Affected by a Product of the Accessory Gene Regulator (Agr) and by Glucose. Infect. Immun. 1991, 59, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etter, D.; Jenni, C.; Edwards, V.; Greutmann, M.; Waltenspül, T.; Tasara, T.; Johler, S. Stress Lowers Staphylococcal Enterotoxin C Production Independently of Agr, SarA, and SigB. J. Food Prot. 2023, 86, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etter, D.; Büchel, R.; Patt, T.; Biggel, M.; Tasara, T.; Cernela, N.; Stevens, M.J.A.; Johler, S. Nitrite Stress Increases Staphylococcal Enterotoxin C Transcription and Triggers the SigB Regulon. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2022, 369, fnac059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, W.; Hanson, D.J.; Drake, M.A. Effect of Salt and Sodium Nitrite on Growth and Enterotoxin Production of Staphylococcus aureus during the Production of Air-Dried Fresh Pork Sausage. J. Food Prot. 2008, 71, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, R.L.; Solberg, M. Interaction of Sodium Nitrate, Oxygen and pH on Growth of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Food Sci. 1972, 37, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeaki, N.; Johler, S.; Skandamis, P.N.; Schelin, J. The Role of Regulatory Mechanisms and Environmental Parameters in Staphylococcal Food Poisoning and Resulting Challenges to Risk Assessment. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoe, K.; Hu, D.L.; Ono, H.K.; Shimizu, S.; Takahashi-Omoe, H.; Nakane, A.; Uchiyama, T.; Shinagawa, K.; Imanishi, K. Emetic Potentials of Newly Identified Staphylococcal Enterotoxin-like Toxins. Infect. Immun. 2013, 81, 3627–3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.L.; Wang, L.; Fang, R.; Okamura, M.; Ono, H.K. Staphylococcus aureus Enterotoxins. In Staphylococcus Aureus; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergdoll, M.S. The Staphylococcal Toxins in Human Disease. In Enteric Infections and Immunity. Infectious Agents and Pathogenesis; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, M.; Li, X.; Han, Z.; Fu, X.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C. Continuous Oral Administration of the Superantigen Staphylococcal Enterotoxin C2 Activates Intestinal Immunity and Modulates the Gut Microbiota in Mice. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2405039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Park, N.; Park, J.Y.; Kaplan, B.L.F.; Pruett, S.B.; Park, J.W.; Park, Y.H.; Seo, K.S. Induction of Immunosuppressive CD8+CD25+FOXP3+ Regulatory T Cells by Suboptimal Stimulation with Staphylococcal Enterotoxin C1. J. Immunol. 2018, 200, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Qiu, Y.; Yang, H. CD4CD8αα IELs: They Have Something to Say. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.-H.; Wan, J.; Zhou, Y.-L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Q.-J.; Liu, L.-G.; Chen, D.; Huang, Y.-P.; Gu, S.; Li, M.-M. Mediated Curing Strategy: An Overview of Salt Reduction for Dry-Cured Meat Products. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 4565–4580. [Google Scholar]

- Lis, E.; Podkowik, M.; Schubert, J.; Bystroń, J.; Stefaniak, T.; Bania, J. Production of Staphylococcal Enterotoxin R by Staphylococcus aureus Strains. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2012, 9, 762–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, P.; Tabiś, A.; Fijałkowski, K.; Masiuk, H.; Łopusiewicz, Ł.; Pruss, A.; Sienkiewicz, M.; Wardach, M.; Kurzawski, M.; Guenther, S.; et al. Regulatory and Enterotoxin Gene Expression and Enterotoxins Production in Staphylococcus aureus FRI913 Cultures Exposed to a Rotating Magnetic Field and Trans-Anethole. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaffl, M.W. A New Mathematical Model for Relative Quantification in Real-Time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, G.V.; Bastos, C.P.; da Silva, W.P. The Effect of Sodium Chloride and Temperature on the Levels of Transcriptional Expression of Staphylococcal Enterotoxin Genes in Staphylococcus aureus Isolates from Broiler Carcasses. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2021, 52, 2343–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tabiś, A.; Seo, K.S.; Lee, J.; Park, J.Y.; Park, N.; Bania, J. Do Food Preservatives Affect Staphylococcal Enterotoxin C Production Equally? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11659. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311659

Tabiś A, Seo KS, Lee J, Park JY, Park N, Bania J. Do Food Preservatives Affect Staphylococcal Enterotoxin C Production Equally? International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11659. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311659

Chicago/Turabian StyleTabiś, Aleksandra, Keun Seok Seo, Juyeun Lee, Joo Youn Park, Nogi Park, and Jacek Bania. 2025. "Do Food Preservatives Affect Staphylococcal Enterotoxin C Production Equally?" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11659. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311659

APA StyleTabiś, A., Seo, K. S., Lee, J., Park, J. Y., Park, N., & Bania, J. (2025). Do Food Preservatives Affect Staphylococcal Enterotoxin C Production Equally? International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11659. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311659