Involvement of Phytochrome-Interacting Factors in High-Irradiance Adaptation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Plant Material

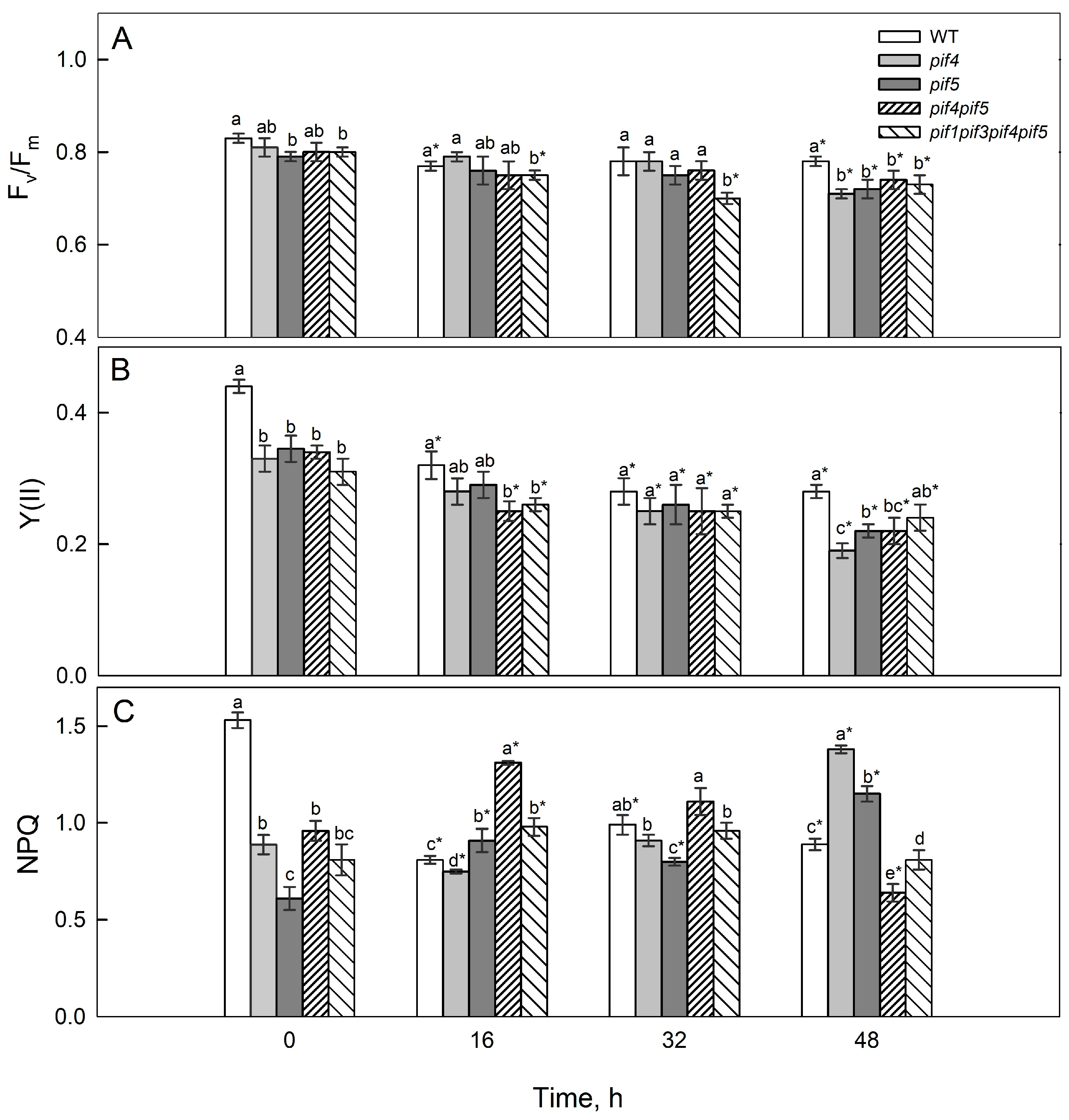

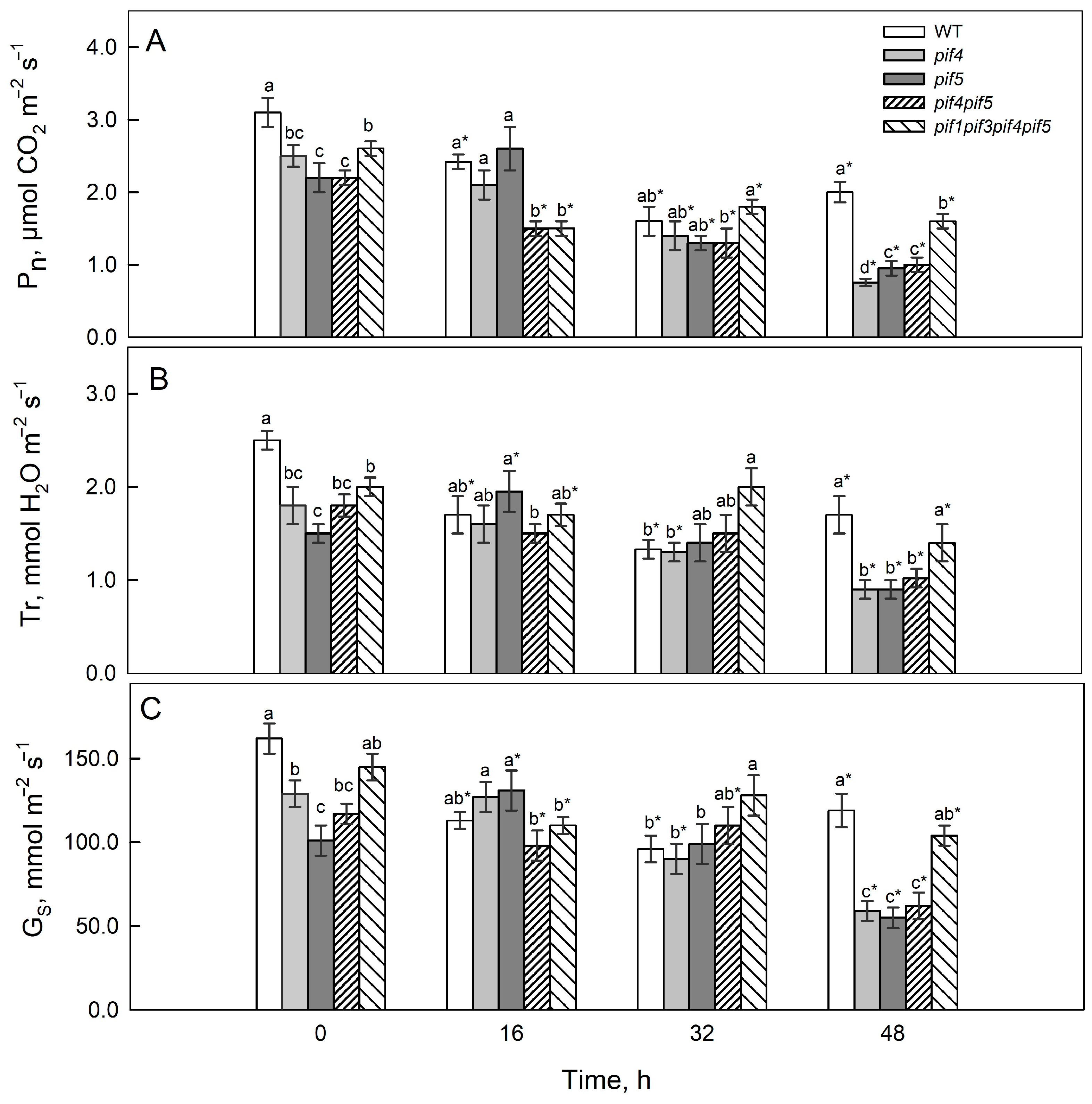

2.2. Photosynthetic Activity and Chl Fluorescence Parameters

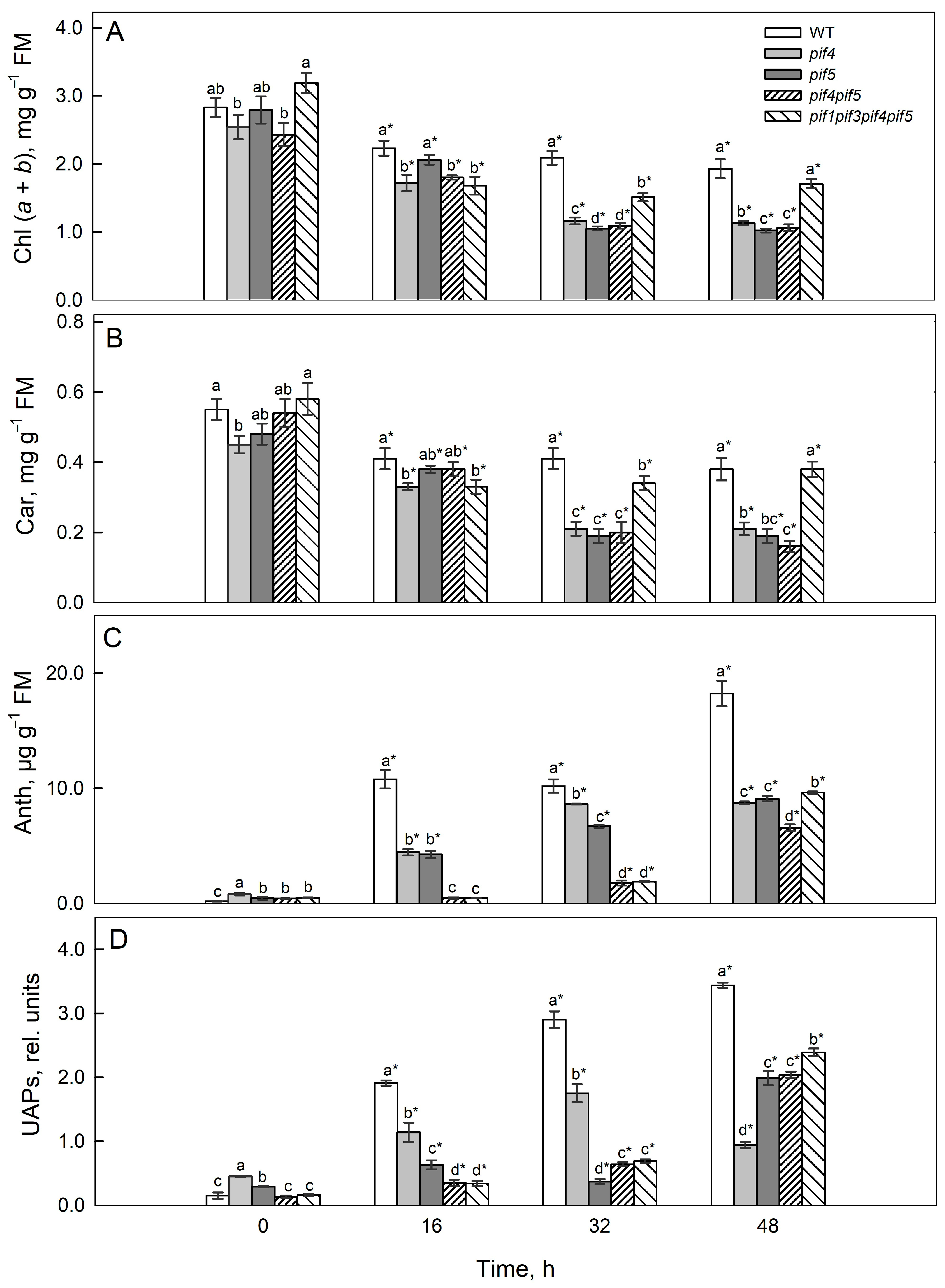

2.3. Pigment Content

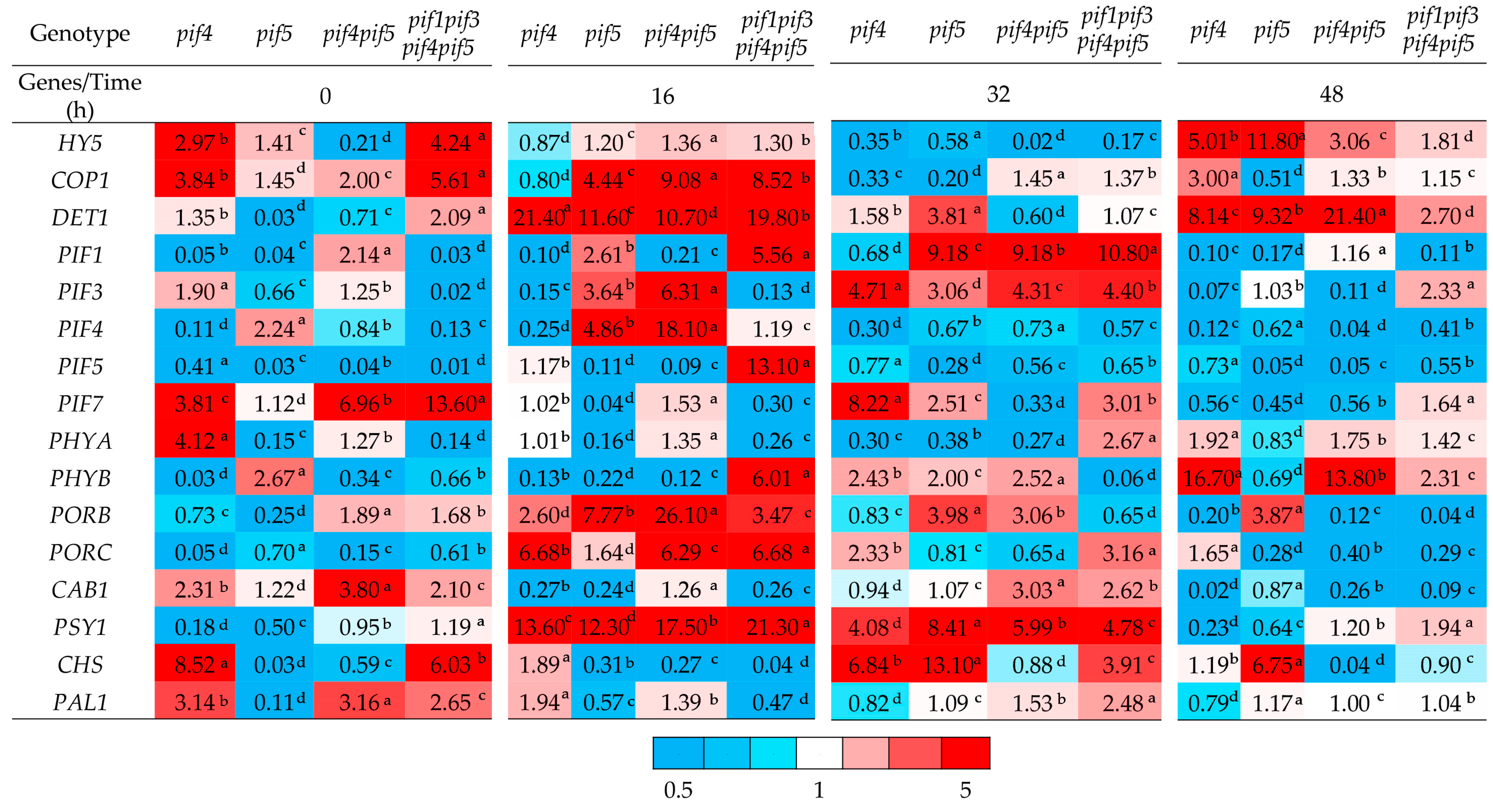

2.4. Gene Expression

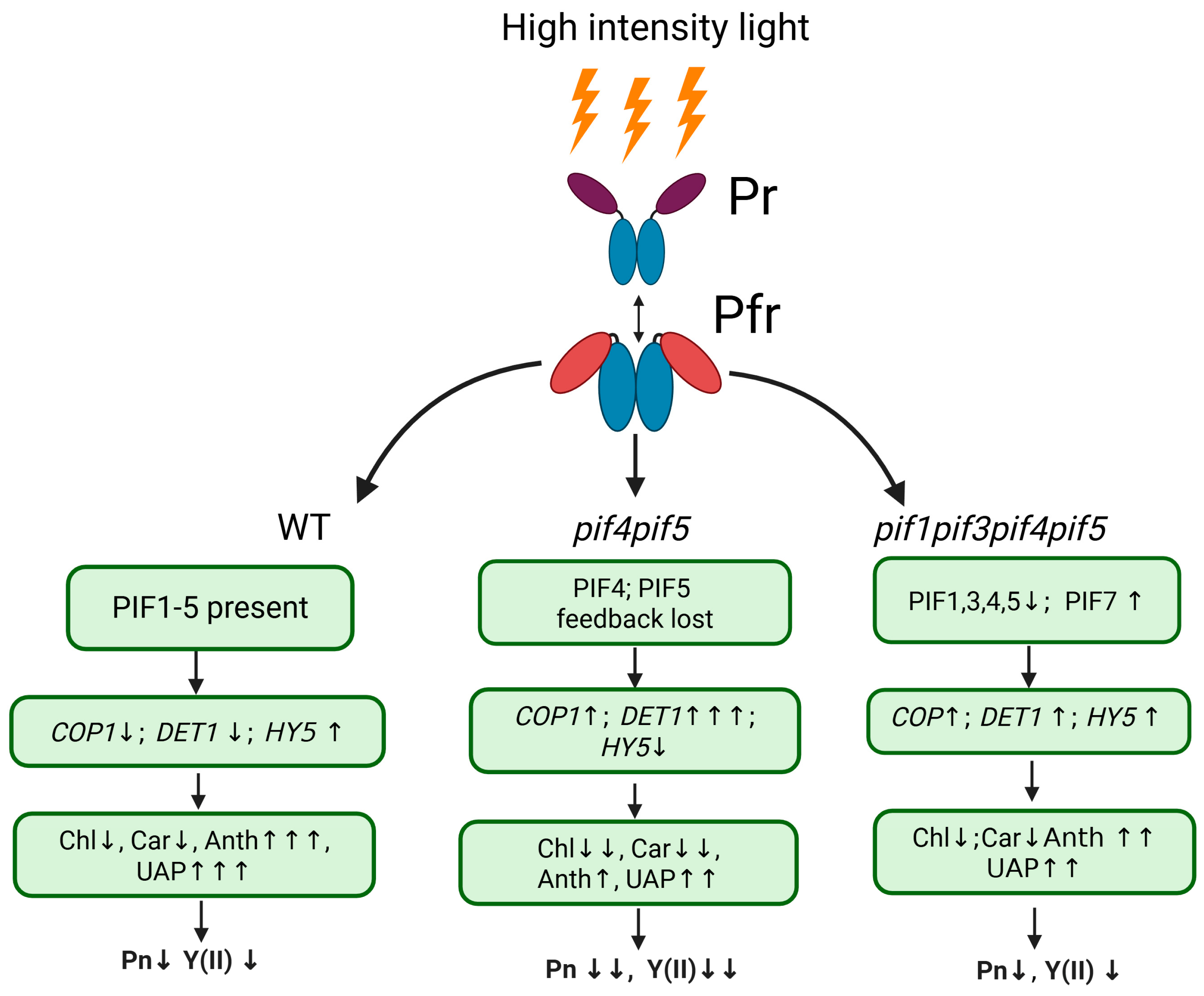

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Growing Conditions

4.2. Determination of Pigment Content

4.3. Photochemical Parameters and Gas Exchange

4.4. RNA Extraction, RT–PCR and Functional Description of Chosen Genes

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kreslavski, V.D.; Shmarev, A.N.; Lyubimov, V.Y.; Semenova, G.A.; Zharmukhamedov, S.K.; Shirshikova, G.N.; Khudyakova, A.Y.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. Response of Photosynthetic Apparatus in Arabidopsis thaliana L. Mutant Deficient in Phytochrome A and B to UV-B. Photosynthetica 2018, 56, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, I.; Huq, E. Plant Photoreceptors: Multi-Functional Sensory Proteins and Their Signaling Networks. In Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 92, pp. 114–121. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, G.; Xiang, F.; Fan, Y.; Li, J.; Zhong, S. Light Signal Transduction in Plants: Insights from Phytochrome Nuclear Translocation and Photobody Formation. New Phytol. 2025, 248, 2221–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Chen, L.; Liang, R.; Huang, S.; Li, X.; Huang, B.; Luo, H.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Zhu, H. The Role of Light in Regulating Plant Growth, Development and Sugar Metabolism: A Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 15, 1507628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Gerken, U.; Tang, K.; Philipp, M.; Zurbriggen, M.D.; Köhler, J.; Möglich, A. Plant Phytochrome Interactions Decode Light and Temperature Signals. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 4819–4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Abid, M.A.; Qanmber, G.; Askari, M.; Zhou, L.; Song, Y.; Liang, C.; Meng, Z.; Malik, W.; Wei, Y.; et al. Photomorphogenesis in Plants: The Central Role of Phytochrome Interacting Factors (PIFs). Environ. Exp. Bot. 2022, 194, 104704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Choi, G. Phytochrome-Interacting Factors Have Both Shared and Distinct Biological Roles. Mol. Cells 2013, 35, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, W.; Xu, S.-L.; Chalkley, R.J.; Pham, T.N.D.; Guan, S.; Maltby, D.A.; Burlingame, A.L.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Quail, P.H. Multisite Light-Induced Phosphorylation of the Transcription Factor PIF3 Is Necessary for Both Its Rapid Degradation and Concomitant Negative Feedback Modulation of Photoreceptor phyB Levels in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 2679–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kang, H.; Park, J.; Kim, W.; Yoo, J.; Lee, N.; Kim, J.; Yoon, T.; Choi, G. PIF1-Interacting Transcription Factors and Their Binding Sequence Elements Determine the in Vivo Targeting Sites of PIF1. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 1388–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, E.; Kim, J.; Park, E.; Kim, J.-I.; Kang, C.; Choi, G. PIL5, a Phytochrome-Interacting Basic Helix-Loop-Helix Protein, Is a Key Negative Regulator of Seed Germination in Arabidopsis thaliana [W]. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 3045–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.V.; Lucyshyn, D.; Jaeger, K.E.; Alós, E.; Alvey, E.; Harberd, N.P.; Wigge, P.A. Transcription Factor PIF4 Controls the Thermosensory Activation of Flowering. Nature 2012, 484, 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lucas, M.; Davière, J.-M.; Rodríguez-Falcón, M.; Pontin, M.; Iglesias-Pedraz, J.M.; Lorrain, S.; Fankhauser, C.; Blázquez, M.A.; Titarenko, E.; Prat, S. A Molecular Framework for Light and Gibberellin Control of Cell Elongation. Nature 2008, 451, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leivar, P.; Monte, E.; Cohn, M.M.; Quail, P.H. Phytochrome Signaling in Green Arabidopsis Seedlings: Impact Assessment of a Mutually Negative phyB–PIF Feedback Loop. Mol. Plant 2012, 5, 734–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvāo, V.C.; Fiorucci, A.-S.; Trevisan, M.; Franco-Zorilla, J.M.; Goyal, A.; Schmid-Siegert, E.; Solano, R.; Fankhauser, C. PIF Transcription Factors Link a Neighbor Threat Cue to Accelerated Reproduction in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, A.; Shi, H.; Tepperman, J.M.; Zhang, Y.; Quail, P.H. Combinatorial Complexity in a Transcriptionally Centered Signaling Hub in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2014, 7, 1598–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo-Ortiz, G.; Johansson, H.; Lee, K.P.; Bou-Torrent, J.; Stewart, K.; Steel, G.; Rodríguez-Concepción, M.; Halliday, K.J. The HY5-PIF Regulatory Module Coordinates Light and Temperature Control of Photosynthetic Gene Transcription. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Park, E.; Choi, G. PIF3 Regulates Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in an HY5-Dependent Manner with Both Factors Directly Binding Anthocyanin Biosynthetic Gene Promoters in Arabidopsis: Functional Relationship between PIF3 and HY5. Plant J. 2007, 49, 981–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Liu, S.; Li, C.; Fu, J.; Jing, Y.; Cheng, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, D.; Wang, X.; Dong, X.; et al. PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTORS Interact with the ABA Receptors PYL8 and PYL9 to Orchestrate ABA Signaling in Darkness. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, H.; Singh, M.B.; Bhalla, P.L. PIF4 and Phytohormones Signalling under Abiotic Stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2024, 228, 106016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-Y.; Ma, N.; Zhang, F.-J.; Li, L.-Z.; Li, H.-J.; Wang, X.-F.; Zhang, Z.; You, C.-X. Functions of Phytochrome Interacting Factors (PIFs) in Adapting Plants to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. IJMS 2024, 25, 2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xin, X.; Qi, L.; Guo, H.; Li, J.; Yang, S. PIF3 Is a Negative Regulator of the CBF Pathway and Freezing Tolerance in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E6695–E6702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pashkovskiy, P.; Kreslavski, V.; Khudyakova, A.; Pojidaeva, E.S.; Kosobryukhov, A.; Kuznetsov, V.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. Independent Responses of Photosynthesis and Plant Morphology to Alterations of PIF Proteins and Light-Dependent MicroRNA Contents in Arabidopsis Thaliana Pif Mutants Grown under Lights of Different Spectral Compositions. Cells 2022, 11, 3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Li, M.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fang, Y. Coordinated Regulation of Arabidopsis microRNA Biogenesis and Red Light Signaling through Dicer-like 1 and Phytochrome-Interacting Factor 4. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14, e1007247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semer, J.; Navrátil, M.; Špunda, V.; Štroch, M. Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters to Assess Utilization of Excitation Energy in Photosystem II Independently of Changes in Leaf Absorption. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2019, 197, 111535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garab, G. Revisiting the QA Model of Chlorophyll-a Fluorescence Induction: New Perspectives to Monitor the Photochemical Activity and Structural Dynamics of Photosystem II. Photosynth. Res. 2025, 163, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garab, G.; Magyar, M.; Sipka, G.; Lambrev, P.H. New Foundations for the Physical Mechanism of Variable Chlorophyll a Fluorescence. Quantum Efficiency versus the Light-Adapted State of Photosystem II. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 5458–5471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavassi, M.A.; Monteiro, C.C.; Campos, M.L.; Melo, H.C.; Carvalho, R.F. Phytochromes Are Key Regulators of Abiotic Stress Responses in Tomato. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 222, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, R.; Ślesak, I.; Orzechowska, A.; Kruk, J. Physiological and Biochemical Responses to High Light and Temperature Stress in Plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017, 139, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didaran, F.; Kordrostami, M.; Ghasemi-Soloklui, A.A.; Pashkovskiy, P.; Kreslavski, V.; Kuznetsov, V.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. The Mechanisms of Photoinhibition and Repair in Plants under High Light Conditions and Interplay with Abiotic Stressors. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2024, 259, 113004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustaka, J.; Moustakas, M. ROS Generation in the Light Reactions of Photosynthesis Triggers Acclimation Signaling to Environmental Stress. Photochem 2025, 5, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Ruban, A.V. Nonphotochemical Chlorophyll Fluorescence Quenching: Mechanism and Effectiveness in Protecting Plants from Photodamage. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 1903–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welc, R.; Luchowski, R.; Kluczyk, D.; Zubik-Duda, M.; Grudzinski, W.; Maksim, M.; Reszczynska, E.; Sowinski, K.; Mazur, R.; Nosalewicz, A.; et al. Mechanisms Shaping the Synergism of Zeaxanthin and PsbS in Photoprotective Energy Dissipation in the Photosynthetic Apparatus of Plants. Plant J. 2021, 107, 418–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhou, L.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, N.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, M.; Wang, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, A.; Li, H.; et al. Phytochrome Interacting Factor Regulates Stomatal Aperture by Coordinating Red Light and Abscisic Acid. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 4293–4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.; Zulfiqar, F.; Raza, A.; Mohsin, S.; Mahmud, J.; Fujita, M.; Fotopoulos, V. Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Defense in Plants under Abiotic Stress: Revisiting the Crucial Role of a Universal Defense Regulator. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovchenko, A. Photoprotection in Plants: Optical Screening-Based Mechanisms; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; ISBN 978-3-642-13887-4. [Google Scholar]

- Toledo-Ortiz, G.; Huq, E.; Rodríguez-Concepción, M. Direct Regulation of Phytoene Synthase Gene Expression and Carotenoid Biosynthesis by Phytochrome-Interacting Factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 11626–11631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leivar, P.; Monte, E. PIFs: Systems Integrators in Plant Development. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, M.; Tattini, M.; Gould, K.S. Multiple Functional Roles of Anthocyanins in Plant-Environment Interactions. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2015, 119, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agati, G.; Brunetti, C.; Di Ferdinando, M.; Ferrini, F.; Pollastri, S.; Tattini, M. Functional Roles of Flavonoids in Photoprotection: New Evidence, Lessons from the Past. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 72, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnu, J.; Hoecker, U. Illuminating the COP1/SPA Ubiquitin Ligase: Fresh Insights Into Its Structure and Functions During Plant Photomorphogenesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 662793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashikhmin, A.; Bolshakov, M.; Pashkovskiy, P.; Vereshchagin, M.; Khudyakova, A.; Shirshikova, G.; Kozhevnikova, A.; Kosobryukhov, A.; Kreslavski, V.; Kuznetsov, V.; et al. The Adaptive Role of Carotenoids and Anthocyanins in Solanum Lycopersicum Pigment Mutants under High Irradiance. Cells 2023, 12, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornitschek, P.; Kohnen, M.V.; Lorrain, S.; Rougemont, J.; Ljung, K.; López-Vidriero, I.; Franco-Zorrilla, J.M.; Solano, R.; Trevisan, M.; Pradervand, S. Phytochrome Interacting Factors 4 and 5 Control Seedling Growth in Changing Light Conditions by Directly Controlling Auxin Signaling. Plant J. 2012, 71, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leivar, P.; Monte, E.; Al-Sady, B.; Carle, C.; Storer, A.; Alonso, J.M.; Ecker, J.R.; Quail, P.H. The Arabidopsis Phytochrome-Interacting Factor PIF7, Together with PIF3 and PIF4, Regulates Responses to Prolonged Red Light by Modulating phyB Levels. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Bo, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L. PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTORS PIF4 and PIF5 Promote Heat Stress Induced Leaf Senescence in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 4577–4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, R.; Shen, Y.; Toledo-Ortiz, G.; Kikis, E.A.; Johannesson, H.; Hwang, Y.-S.; Quail, P.H. Functional Profiling Reveals That Only a Small Number of Phytochrome-Regulated Early-Response Genes in Arabidopsis Are Necessary for Optimal Deetiolation. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 2157–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, R.; Shen, Y.; Marion, C.M.; Tsuchisaka, A.; Theologis, A.; Schäfer, E.; Quail, P.H. The Basic Helix-Loop-Helix Transcription Factor PIF5 Acts on Ethylene Biosynthesis and Phytochrome Signaling by Distinct Mechanisms. Plant Cell 2008, 19, 3915–3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Kim, K.; Kang, H.; Zulfugarov, I.S.; Bae, G.; Lee, C.-H.; Lee, D.; Choi, G. Phytochromes Promote Seedling Light Responses by Inhibiting Four Negatively-Acting Phytochrome-Interacting Factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 7660–7665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Mayba, O.; Pfeiffer, A.; Shi, H.; Tepperman, J.M.; Speed, T.P.; Quail, P.H. A Quartet of PIF bHLH Factors Provides a Transcriptionally Centered Signaling Hub That Regulates Seedling Morphogenesis through Differential Expression-Patterning of Shared Target Genes in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, S.; Wu, S.; Zhang, H.; Mou, M.; Chen, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Yu, D. The PIFs Redundantly Control Plant Defense Response against Botrytis Cinerea in Arabidopsis. Plants 2020, 9, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. [34] Chlorophylls and Carotenoids: Pigments of Photosynthetic Biomembranes. In Methods in Enzymology; Plant Cell Membranes; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1987; Volume 148, pp. 350–382. [Google Scholar]

- Klughammer, C.; Schreiber, U. Complementary PS II Quantum Yields Calculated from Simple Fluorescence Parameters Measured by PAM Fluorometry and the Saturation Pulse Method. PAM Appl. Notes 2008, 1, 201–247. [Google Scholar]

- Abramova, A.; Vereshchagin, M.; Kulkov, L.; Kreslavski, V.D.; Kuznetsov, V.V.; Pashkovskiy, P. Potential Role of Phytochromes A and B and Cryptochrome 1 in the Adaptation of Solanum Lycopersicum to UV-B Radiation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Chu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Bian, Y.; Xiao, J.; Xu, D. HY5: A Pivotal Regulator of Light-Dependent Development in Higher Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 800989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañibano, E.; Bourbousse, C.; Garcia-Leon, M.; Gomez, B.G.; Wolff, L.; García-Baudino, C.; Lozano-Duran, R.; Barneche, F.; Rubio, V.; Fonseca, S. DET1-Mediated COP1 Regulation Avoids HY5 Activity over Second-Site Gene Targets to Tune Plant Photomorphogenesis. Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 963–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koene, S.; Shapulatov, U.; Van Dijk, A.D.J.; Van Der Krol, A.R. Transcriptional Feedback in Plant Growth and Defense by PIFs, BZR1, HY5, and MYC Transcription Factors. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 41, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Rao, S.; Wrightstone, E.; Sun, T.; Lui, A.C.W.; Welsch, R.; Li, L. Phytoene Synthase: The Key Rate-Limiting Enzyme of Carotenoid Biosynthesis in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 884720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Hirschberg, J. The Genetic Components of a Natural Color Palette: A Comprehensive List of Carotenoid Pathway Mutations in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 806184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pashkovskiy, P.; Abramova, A.; Khudyakova, A.; Vereshchagin, M.; Kuznetsov, V.; Kreslavski, V.D. Involvement of Phytochrome-Interacting Factors in High-Irradiance Adaptation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11660. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311660

Pashkovskiy P, Abramova A, Khudyakova A, Vereshchagin M, Kuznetsov V, Kreslavski VD. Involvement of Phytochrome-Interacting Factors in High-Irradiance Adaptation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11660. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311660

Chicago/Turabian StylePashkovskiy, Pavel, Anna Abramova, Alexandra Khudyakova, Mikhail Vereshchagin, Vladimir Kuznetsov, and Vladimir D. Kreslavski. 2025. "Involvement of Phytochrome-Interacting Factors in High-Irradiance Adaptation" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11660. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311660

APA StylePashkovskiy, P., Abramova, A., Khudyakova, A., Vereshchagin, M., Kuznetsov, V., & Kreslavski, V. D. (2025). Involvement of Phytochrome-Interacting Factors in High-Irradiance Adaptation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11660. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311660