Modulation of α-Mannosidase 8 by Antarctic Endophytic Fungi in Strawberry Plants Under Heat Waves and Water Deficit Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

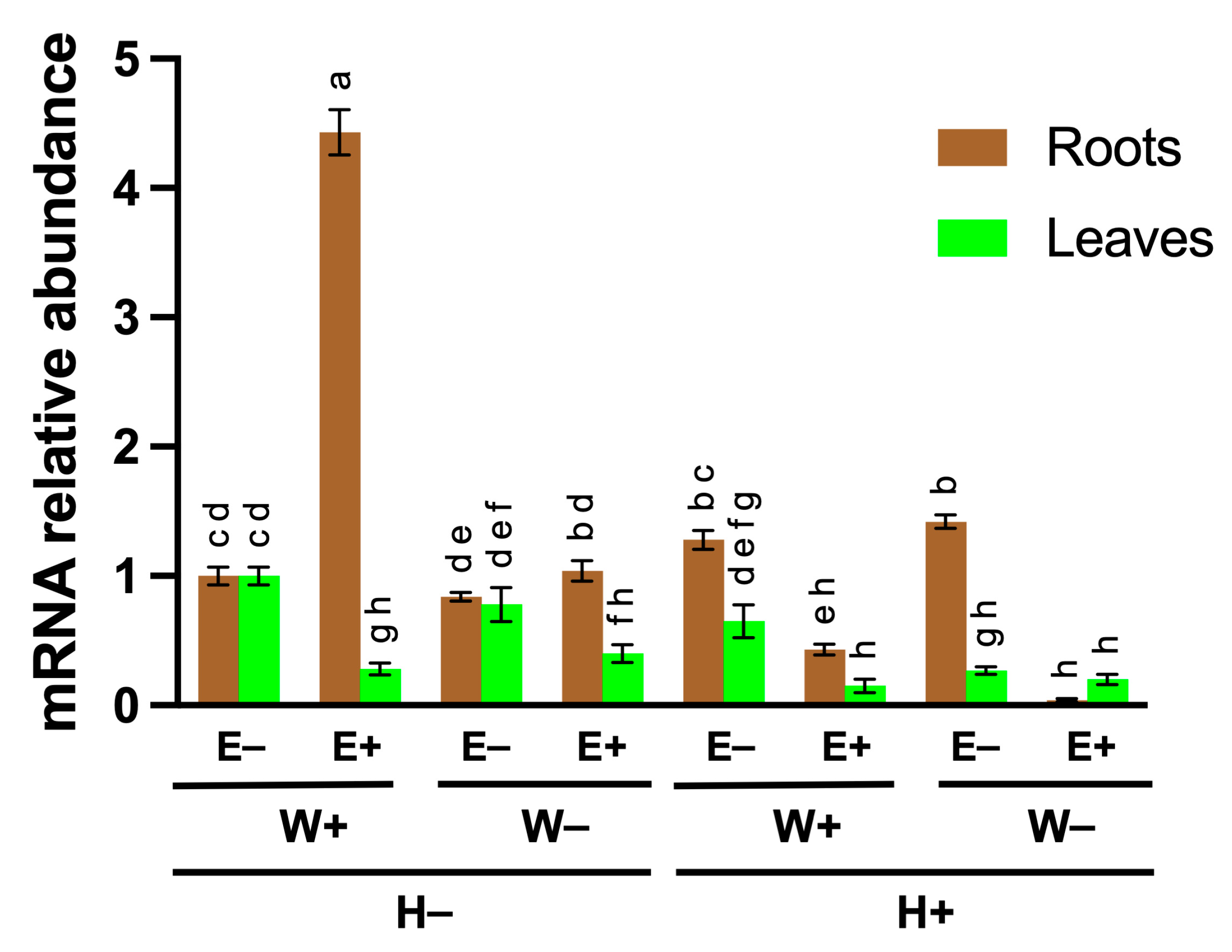

2.1. Expression of FaMAN8 Is Modulated by Endophytic Fungal Interaction

2.2. Structural and Domain Organization of FaMAN8 Reveals Structural Conservation with Jack Bean α-Mannosidase

2.3. Protein-Ligand Evaluation Suggests Conserved Substrate-Binding Pocket in FaMAN8

2.4. Electrostatic Surface Potential Evaluations

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant and Fungal Material

4.2. Identification of α-Mannosidase Transcripts in the Strawberry Transcriptome

4.3. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

4.4. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR) Analysis

4.5. Structural and Bioinformatics Characterization of FaMAN8

4.5.1. Protein Structure Modelling

4.5.2. Protein Preparation

4.5.3. Ligand Conformation

4.5.4. Ligand Docking

4.5.5. System Preparation and Molecular Dynamics Preparation

4.5.6. Computational Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, X.M.; Sharma, A.; Liu, H. The Impact of Climate Change on Environmental Sustainability and Human Mortality. Environments 2023, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, K.; Qasim, M.Z.; Song, H.; Murshed, M.; Mahmood, H.; Younis, I. A review of the global climate change impacts, adaptation, and sustainable mitigation measures. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 42539–42559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNFCCC (s.f.). Introduction to Adaptation and Resilience. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Available online: https://unfccc.int/topics/adaptation-and-resilience/the-big-picture/introduction (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Gao, L.; Kantar, M.B.; Moxley, D.; Ortiz-Barrientos, D.; Rieseberg, L.H. Crop adaptation to climate change: An evolutionary perspective. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1518–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karavolias, N.G.; Horner, W.; Abugu, M.N.; Evanega, S.N. Application of Gene Editing for Climate Change in Agriculture. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 685801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Lin, F.; Su, Z. Endophytic fungi—Big player in plant-microbe symbiosis. Curr. Plant Biol. 2025, 42, 100481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Luo, D.; Li, X.Q.; Han, T.; Jia, M.; Kong, Z.Y.; Ji, J.C.; Rahman, K.; Qin, L.P.; Zheng, C.J. Endophyte Chaetomium globosum D38 promotes bioactive constituents accumulation and root production in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 302133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Wu, Y.; Zhai, X.; Zhang, R.; Wu, J.; Zhang, C.; Rahman, K.; Qin, L.; Han, T.; Zheng, C. Beneficial Effects of Endophytic Fungi from the Anoectochilus and Ludisia Species on the Growth and Secondary Metabolism of Anoectochilus roxburghii. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 3487–3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, J.; Song, J.; Sun, Q.; Zhu, B.; Qin, L. Exogenous and Endophytic Fungal Communities of Dendrobium nobile Lindl. across Different Habitats and Their Enhancement of Host Plants’ Dendrobine Content and Biomass Accumulation. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 12489–12500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Vargas, A.T.; López-Ramírez, V.; Álvarez-Mejía, C.; Vázquez-Martínez, J. Endophytic Fungi for Crops Adaptation to Abiotic Stresses. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giauque, H.; Connor, E.W.; Hawkes, C.V. Endophyte traits relevant to stress tolerance, resource use and habitat of origin predict effects on host plants. New Phytol. 2019, 221, 2239–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña-Rodríguez, I.S.; Ballesteros, G.I.; Atala, C.; Gundel, P.E.; Molina-Montenegro, M.A. Hardening Blueberry Plants to Face Drought and Cold Events by the Application of Fungal Endophytes. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbontín, C.; Flores, S.; Reyes, M.; Urrutia, V.; Parra-Palma, C.; Morales-Quintana, L.; Ramos, P. Antarctic fungal inoculation enhances drought tolerance and modulates fruit physiology in blueberry plants. Curr. Plant Biol. 2025, 42, 100462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Montenegro, M.A.; Acuña-Rodríguez, I.S.; Torres-Díaz, C.; Gundel, P.E.; Dreyer, I. Antarctic root endophytes improve physiological performance and yield in crops under salt stress by enhanced energy production and Na+ sequestration. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Quintana, L.; Moya, M.; Santelices-Moya, R.; Cabrera-Ariza, A.; Rabert, C.; Pollmann, S.; Ramos, P. Improvement in the physiological and biochemical performance of strawberries under drought stress through symbiosis with Antarctic fungal endophytes. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 939955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San Miguel, Y.; Santelices-Moya, R.; Cabrera-Ariza, A.M.; Ramos, P. Microbial Allies from the Cold: Antarctic Fungal Endophytes Improve Maize Performance in Water-Limited Fields. Plants 2025, 14, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez, M.A.; Flores, S.; Hormazábal-Abarza, F.; Pollmann, S.; Gundel, P.E.; Cabrera-Ariza, A.; Santelices-Moya, R.; Morales-Quintana, L.; Ramos, P. Antarctic endophytic fungi enhance strawberry resilience to drought and heat stress by modulating aquaporins and dehydrins. Plant Stress 2025, 16, 100805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Xu, J.; Zou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, P.; Li, Q. Differentiation and response mechanisms of the endophytic flora of plants ecologically restored in the ilmenite area. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1555309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, W.; Li, M.; Jiang, L.; Yang, M.; Liu, M.; Liu, Y. Endophytic Bacterial Community Structure and Function Response of BLB Rice Leaves After Foliar Application of Cu-Ag Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, R.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Sun, P.; Lu, B.; Wu, M.; Yan, Z. Endophytic fungal community composition and function response to strawberry genotype and disease resistance. PeerJ 2025, 13, e19383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.M.E.; Mele, M.A.; Lee, Y.-T.; Islam, M.Z. Consumer Preference, Quality, and Safety of Organic and Conventional Fresh Fruits, Vegetables, and Cereals. Foods 2021, 10, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Arriaza, F.; Gil I Cortiella, M.; Pollmann, S.; Morales-Quintana, L.; Ramos, P. Modulation of volatile production in strawberries fruits by endophytic fungi: Insights into modulation of the ester’s biosynthetic pathway under drought condition. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 219, 109347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannoni, J.J. Genetic Regulation of Fruit Development and Ripening. Plant Cell 2004, 16 (Suppl. 1), S170–S180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brummell, D.A. Cell wall disassembly in ripening fruit. Funct. Plant Biol. 2006, 33, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-May, E.; Kim, S.; Brandizzi, F.; Rose, J.K.C. The secreted plant N-glycoproteome and associated secretory pathways. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruíz-May, E.; Thannhauser, T.W.; Zhang, S.; Rose, J.K.C. Analytical technologies for identification and characterization of the plant N-glycoproteome. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 150. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-May, E.; Rose, J.K.C. Cell wall architecture and metabolism in ripening fruit and the complex relationship with softening. In The Molecular Biology and Biochemistry of Fruit Ripening; Seymour, G., Tucker, G.A., Poole, M., Giovannoni, J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2013; pp. 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Yáñez, A.; Sáez, D.; Rodríguez-Arriaza, F.; Letelier-Naritelli, C.; Valenzuela-Riffo, F.; Morales-Quintana, L. Involvement of the GH38 Family Exoglycosidase α-Mannosidase in Strawberry Fruit Ripening. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Quintana, L.; Ramos, P. Chilean strawberry (Fragaria chiloensis): An integrative and comprehensive review. Food Res. Int. 2019, 119, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posé, S.; Paniagua, C.; Matas, A.J.; Gunning, A.P.; Morris, V.J.; Quesada, M.A.; Mercado, J.A. A nanostructural view of the cell wall disassembly process during fruit ripening and postharvest storage by atomic force microscopy. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 87, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Li, B.-J.; Grierson, D.; Chen, K.-S. Insights into cell wall changes during fruit softening from transgenic and naturally occurring mutants. Plant Physiol. 2023, 192, 1671–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebminger, E.; Hüttner, S.; Vavra, U.; Fischl, R.; Schoberer, J.; Grass, J.; Blaukopf, C.; Seifert, G.J.; Altmann, F.; Mach, L.; et al. Class I alpha-mannosidases are required for N-glycan processing and root development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 3850–3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Quintana, L.; Méndez-Yáñez, A. α-Mannosidase and β-d-N-acetylhexosaminidase outside the wall: Partner exoglycosidases involved in fruit ripening process. Plant Mol. Biol. 2023, 112, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Nakano, R.; Nakamura, K.; Hossain, M.T.; Kimura, Y. Molecular characterization of plant acidic-mannosidase, a member of glycosylhydrolase family 38, involved in the turnover of N-glycans during tomato fruit ripening. J. Biochem. 2010, 148, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meli, V.S.; Ghosh, S.; Prabha, T.N.; Chakraborty, N.; Chakraborty, S.; Datta, A. Enhancement of fruit shelf life by suppressingN-glycan processing enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 2413–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Yañez, A.; González, M.; Carrasco-Orellana, C.; Herrera, R.; Moya-León, M.A. Isolation of a rhamnogalacturonan lyase expressed during ripening of the Chilean strawberry fruit and its biochemical characterization. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 146, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Wu, Y.; Shi, R.; Sun, M.; Li, Q.; Zhang, G.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W. Overexpression of wheat α-mannosidase gene TaMP impairs salt tolerance in transgenic Brachypodium distachyon. Plant Cell Rep. 2020, 39, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaswanthi, N.; Krishna, M.S.R.; Sahitya, U.L.; Suneetha, P. Apoplast proteomic analysis reveals drought stress-responsive protein datasets in chilli (Capsicum annuum L.). Data Brief 2019, 25, 104041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, D.; Xu, J. Abiotic stress responses in plant roots: A proteomics perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, E.; Cousido-Siah, A.; Lepage, M.L.; Schneider, J.P.; Bodlenner, A.; Mitschler, A.; Meli, A.; Izzo, I.; Alvarez, H.A.; Podjarny, A.; et al. Structural Basis of Outstanding Multivalent Effects in Jack Bean α-Mannosidase Inhibition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 8002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar, Ş.H.; Ayvaz Sonmez, D.; Akbari, A.; Ergün, D.; Bilgin, Ö.F.; Yeşil, B.; Bozkurt, M.O.; Daşgan, H.Y.; İkiz, B.; Kafkas, S.; et al. Screening of strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) cultivars for drought tolerance based on physiological and biochemical responses under PEG-induced stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 15, 1655320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Palma, C.; Ubeda, C.; Gil, M.; Ramos, P.; Castro, R.I.; Morales-Quintana, L. Comparative study of the volatile organic compounds of four strawberry cultivars and it relation to alcohol acyltransferase enzymatic activity. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 251, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, P.; Parra-Palma, C.; Figueroa, C.R.; Zúñiga, P.E.; Valenzuela-Riffo, F.; González, J.; Gaete-Eastman, C.; Morales-Quintana, L. Cell wall-related enzymatic activities and transcriptional profiles in four strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa) cultivars during fruit development and ripening. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 238, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, H.M.; Westbrook, J.; Feng, Z.; Gilliland, G.; Bhat, T.N.; Weissig, H.; Shindyalov, I.N.; Bourne, P.E. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestro, S. Schrödinger Release 2023-1; Schrödinger LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Jia, X.; Liu, L.; Voglmeir, J. Changes in protein N-glycosylation during the fruit development and ripening in melting-type peach. Food Mater. Res. 2021, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesner, R.A.; Banks, J.L.; Murphy, R.B.; Halgren, T.A.; Klicic, J.J.; Mainz, D.T.; Repasky, M.P.; Knoll, E.H.; Shelley, M.; Perry, J.K.; et al. Glide: A New Approach for Rapid, Accurate Docking and Scoring. 1. Method and Assessment of Docking Accuracy. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 1739–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roos, K.; Wu, C.; Damm, W.; Reboul, M.; Stevenson, J.M.; Lu, C.; Dahlgren, M.K.; Mondal, S.; Chen, W.; Wang, L.; et al. OPLS3e: Extending Force Field Coverage for Drug-Like Small Molecules. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 1863–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhiti, M.; Yang, C.; Chan, A.; Durnin, D.C.; Belmonte, M.F.; Ayele, B.T.; Tahir, M.; Stasolla, C. Altered seed oil and glucosinolate levels in transgenic plants overexpressing the Brassica napus SHOOTMERISTEMLESS gene. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 4447–4461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, N.A.; Sept, D.; Joseph, S.; Holst, M.J.; McCammon, J.A. Electrostatics of nanosystems: Application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 10037–10041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMDVisual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Tian, W.; Wang, B.; Liang, J. CASTpFold: Computed Atlas of Surface Topography of the universe of protein Folds. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W194–W199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, M.P.; Pincus, D.L.; Rapp, C.S.; Day, T.J.F.; Honig, B.; Shaw, D.E.; Friesner, R.A. A hierarchical approach to all-atom protein loop prediction. Proteins 2004, 55, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Protein Cavity Volume | ||

|---|---|---|

| Protein | Area (A2) | Volume (A3) |

| JbMAN | 342.5 ± 192.5 | 211.0 ± 133.7 |

| FaMAN8 | 471.4 ± 357.8 | 575.0 ± 791.1 |

| MM-GBSA Energy Determinations | |

|---|---|

| Energy Type | FaMAN |

| Coulomb | −40.4 ± 17.8 |

| Hydrogen bond | −3.9 ± 1.8 |

| Lipophobic | −10.3 ± 4.9 |

| Polar solvation | 81.7 ± 30.9 |

| Van del Waals | −35.8 ± 15.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bustos, D.; Morales-Quintana, L.; Urra, G.; Arriaza-Rodríguez, F.; Pollmann, S.; Méndez-Yáñez, A.; Ramos, P. Modulation of α-Mannosidase 8 by Antarctic Endophytic Fungi in Strawberry Plants Under Heat Waves and Water Deficit Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311650

Bustos D, Morales-Quintana L, Urra G, Arriaza-Rodríguez F, Pollmann S, Méndez-Yáñez A, Ramos P. Modulation of α-Mannosidase 8 by Antarctic Endophytic Fungi in Strawberry Plants Under Heat Waves and Water Deficit Stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311650

Chicago/Turabian StyleBustos, Daniel, Luis Morales-Quintana, Gabriela Urra, Francisca Arriaza-Rodríguez, Stephan Pollmann, Angela Méndez-Yáñez, and Patricio Ramos. 2025. "Modulation of α-Mannosidase 8 by Antarctic Endophytic Fungi in Strawberry Plants Under Heat Waves and Water Deficit Stress" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311650

APA StyleBustos, D., Morales-Quintana, L., Urra, G., Arriaza-Rodríguez, F., Pollmann, S., Méndez-Yáñez, A., & Ramos, P. (2025). Modulation of α-Mannosidase 8 by Antarctic Endophytic Fungi in Strawberry Plants Under Heat Waves and Water Deficit Stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311650