Creatine Kinase Blockade Disrupts Energy Metabolism and Redox Homeostasis to Suppress Osteosarcoma Progression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

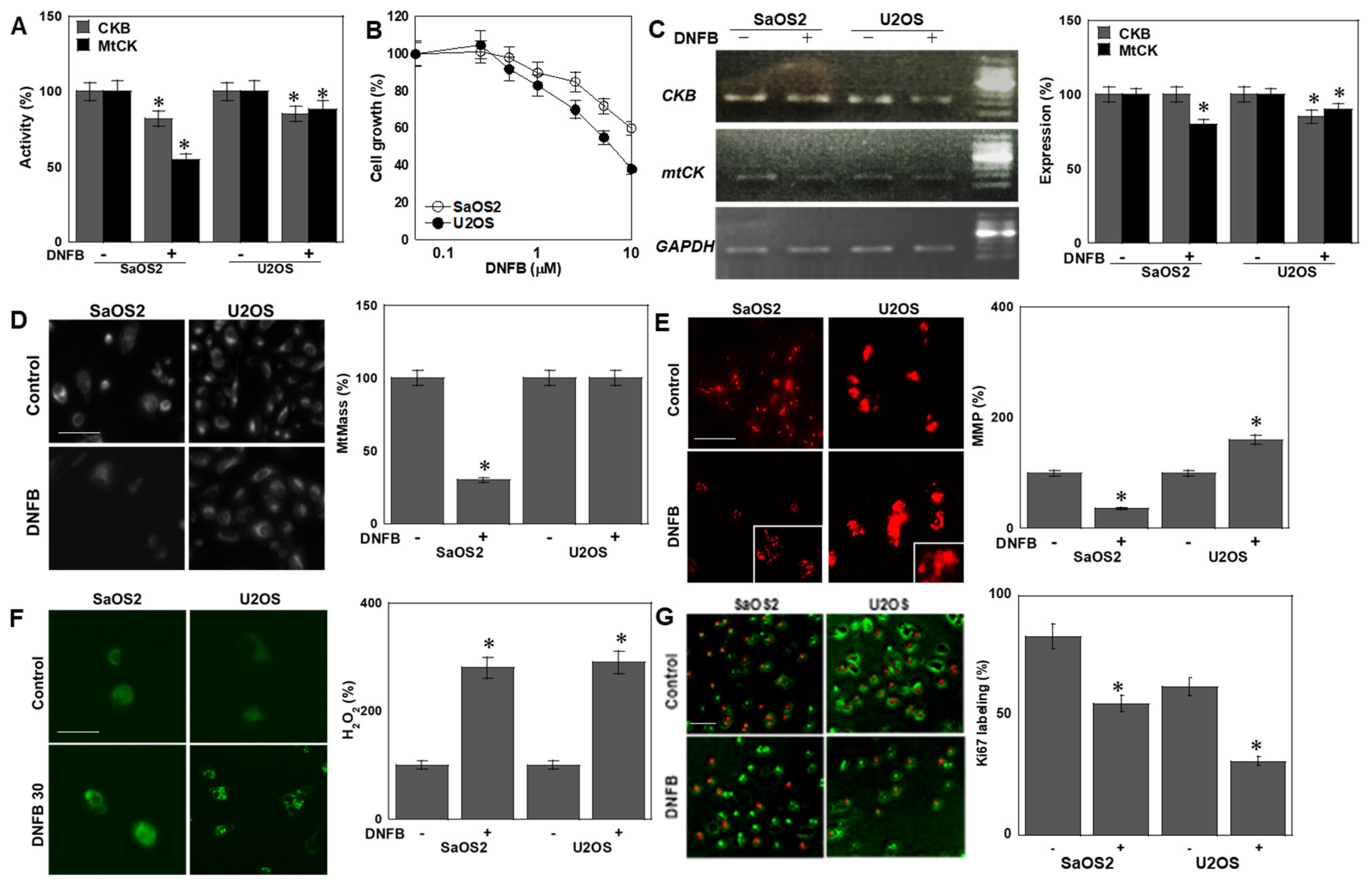

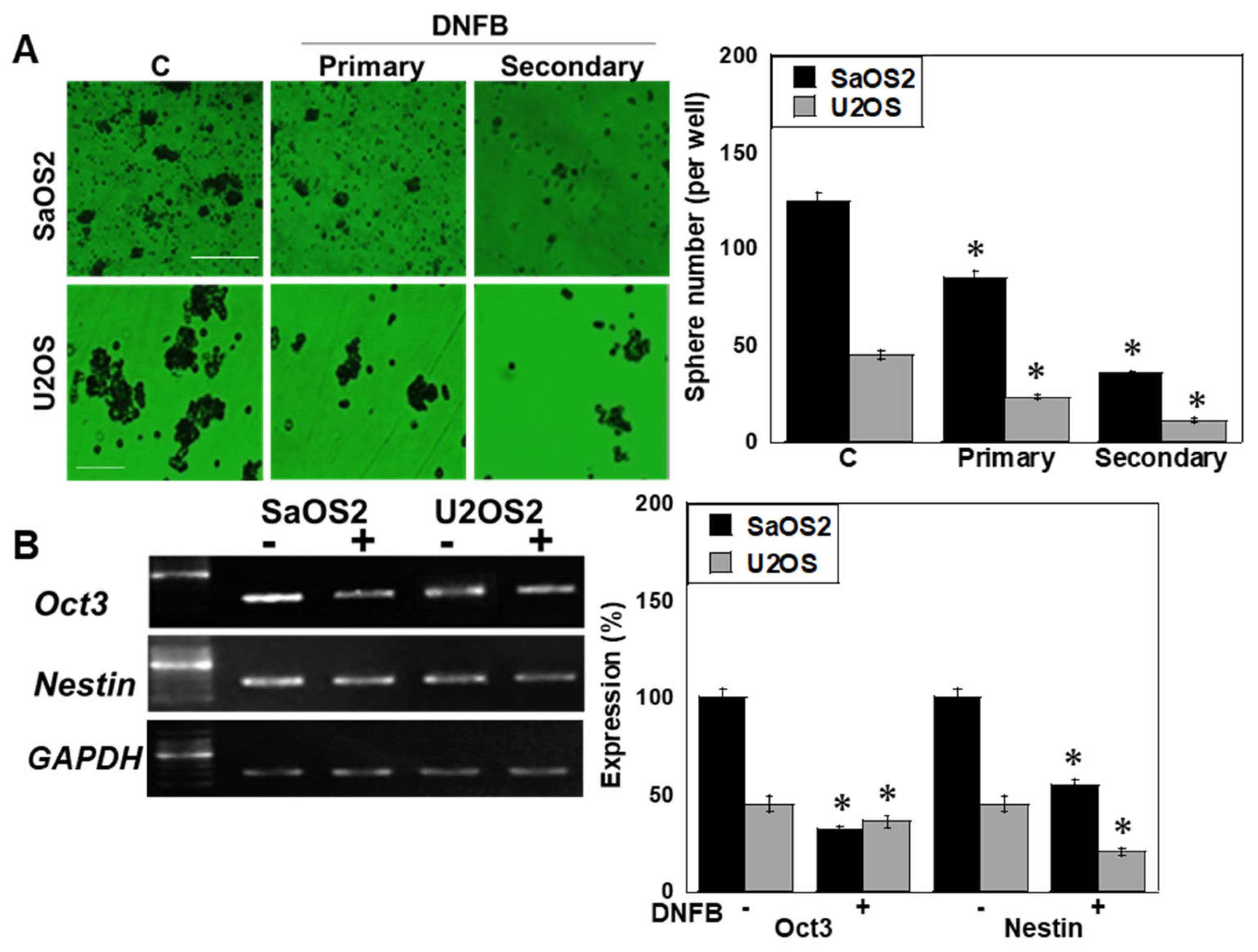

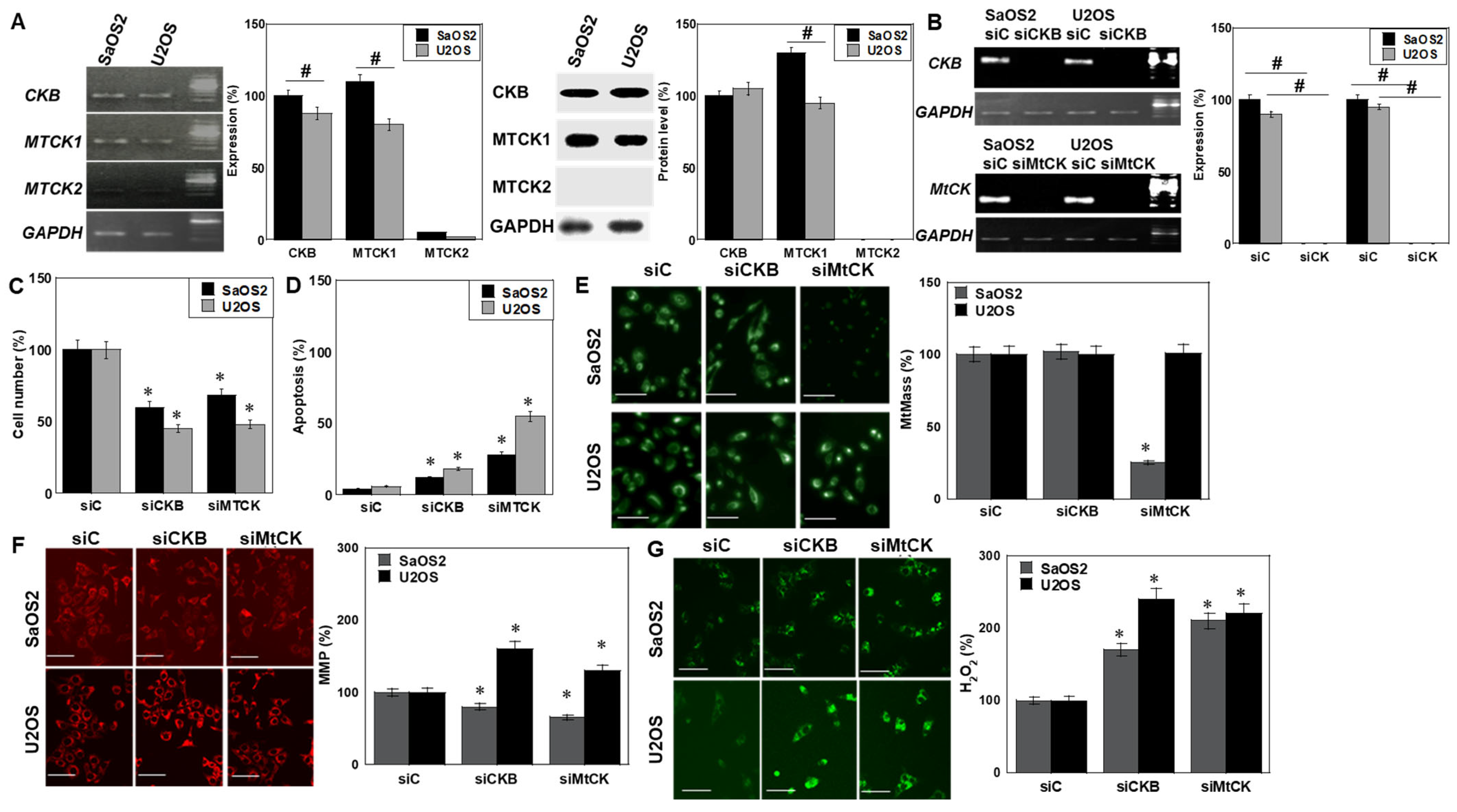

2.1. Effects of CK Inhibition on OS Cells

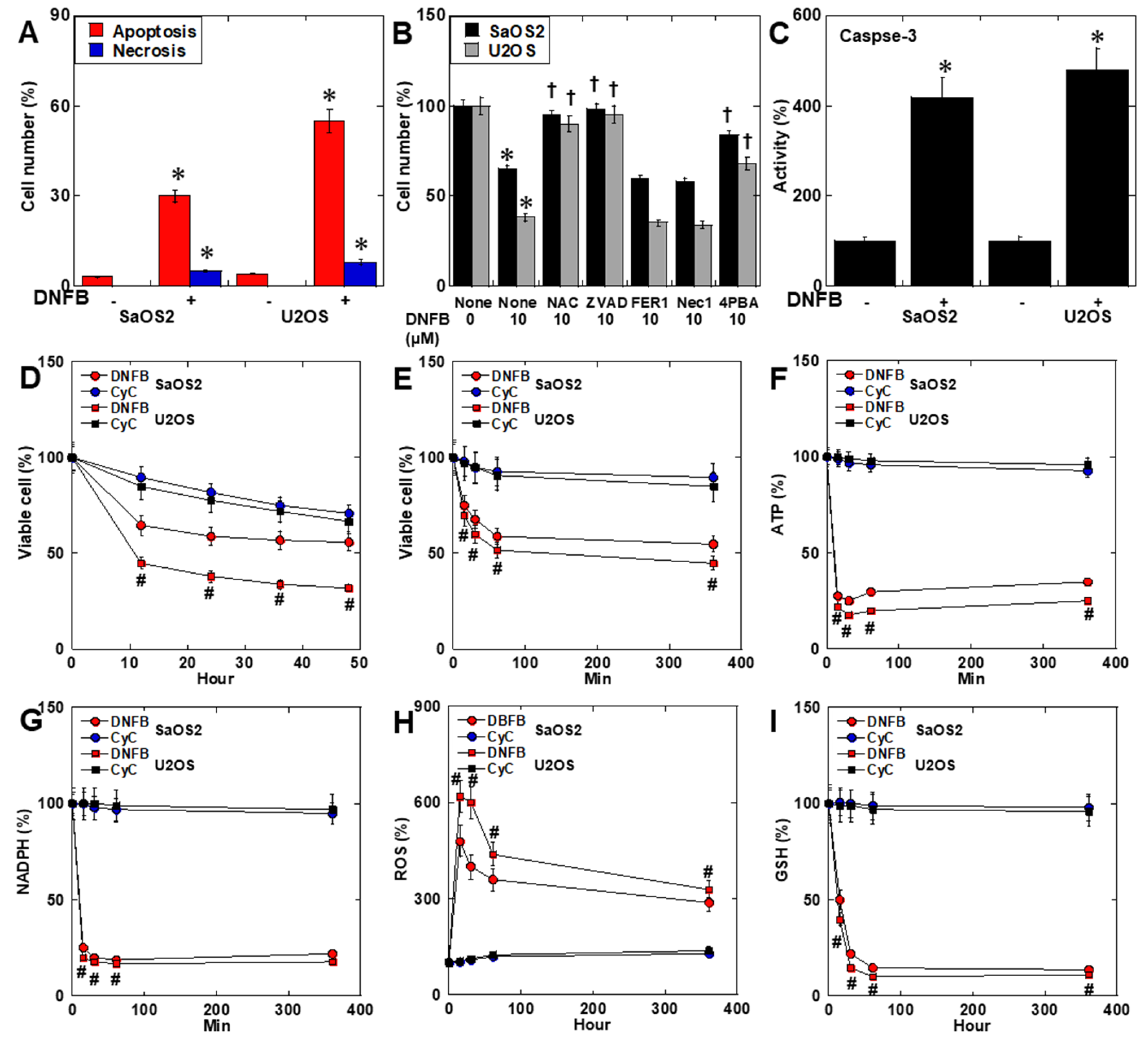

2.2. Effects of CK Inhibition on Cell Death

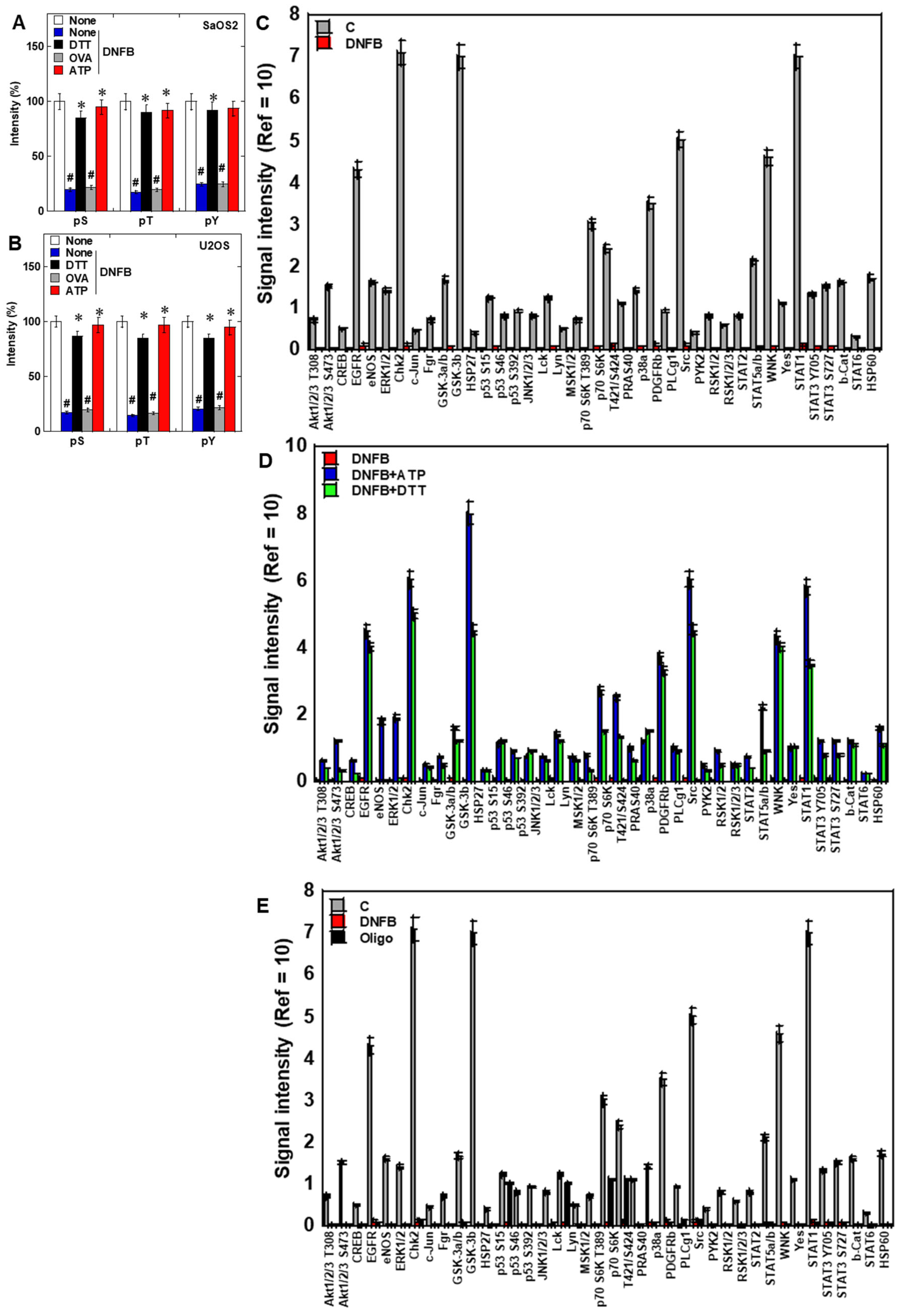

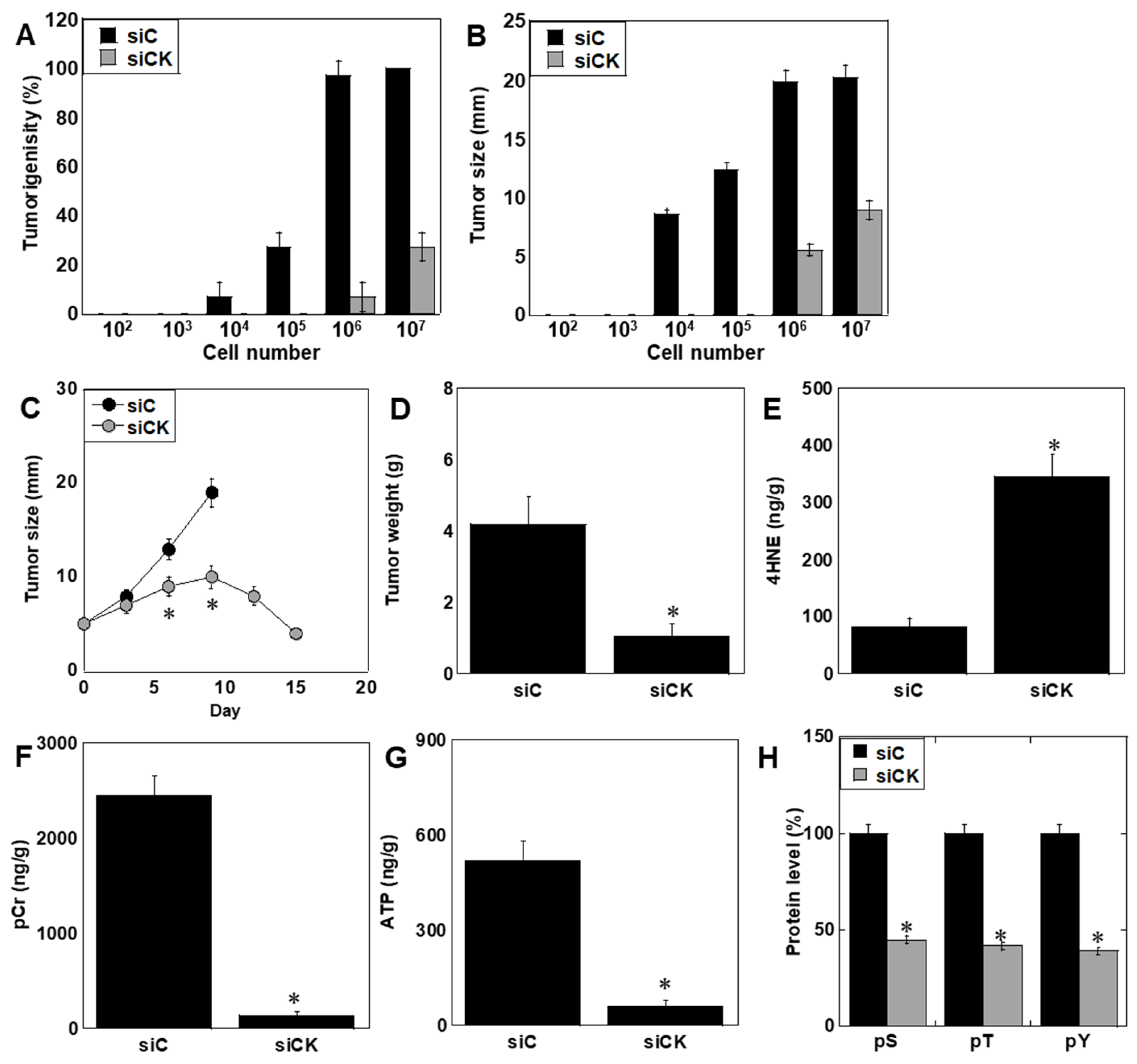

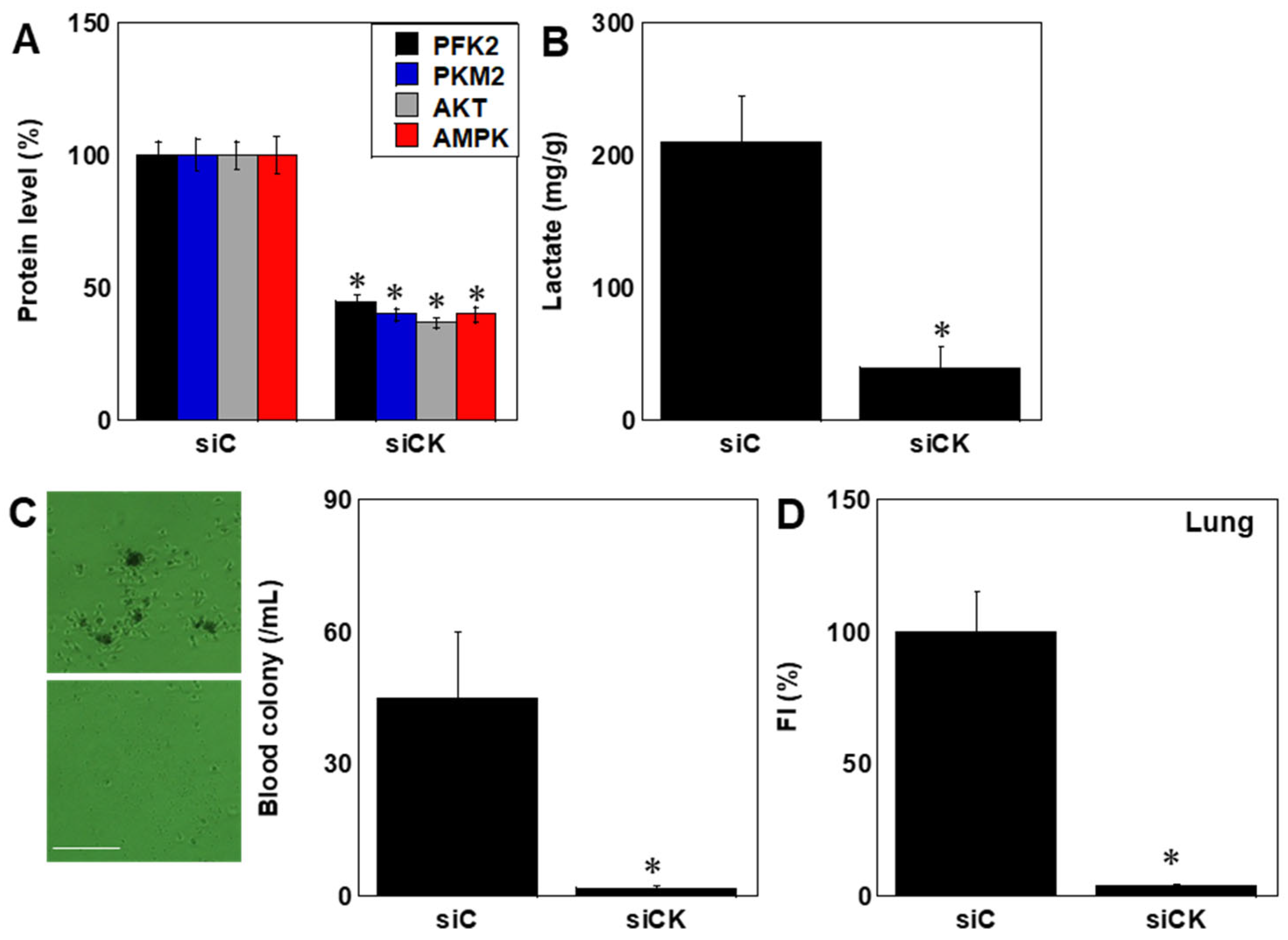

2.3. Effects of CK Inhibition on Phosphorylation Signaling

2.4. Isoform-Specific Effects of CK Knockdown

2.5. CK Specificity of DNFB

2.6. Effects of CK Inhibition In Vivo

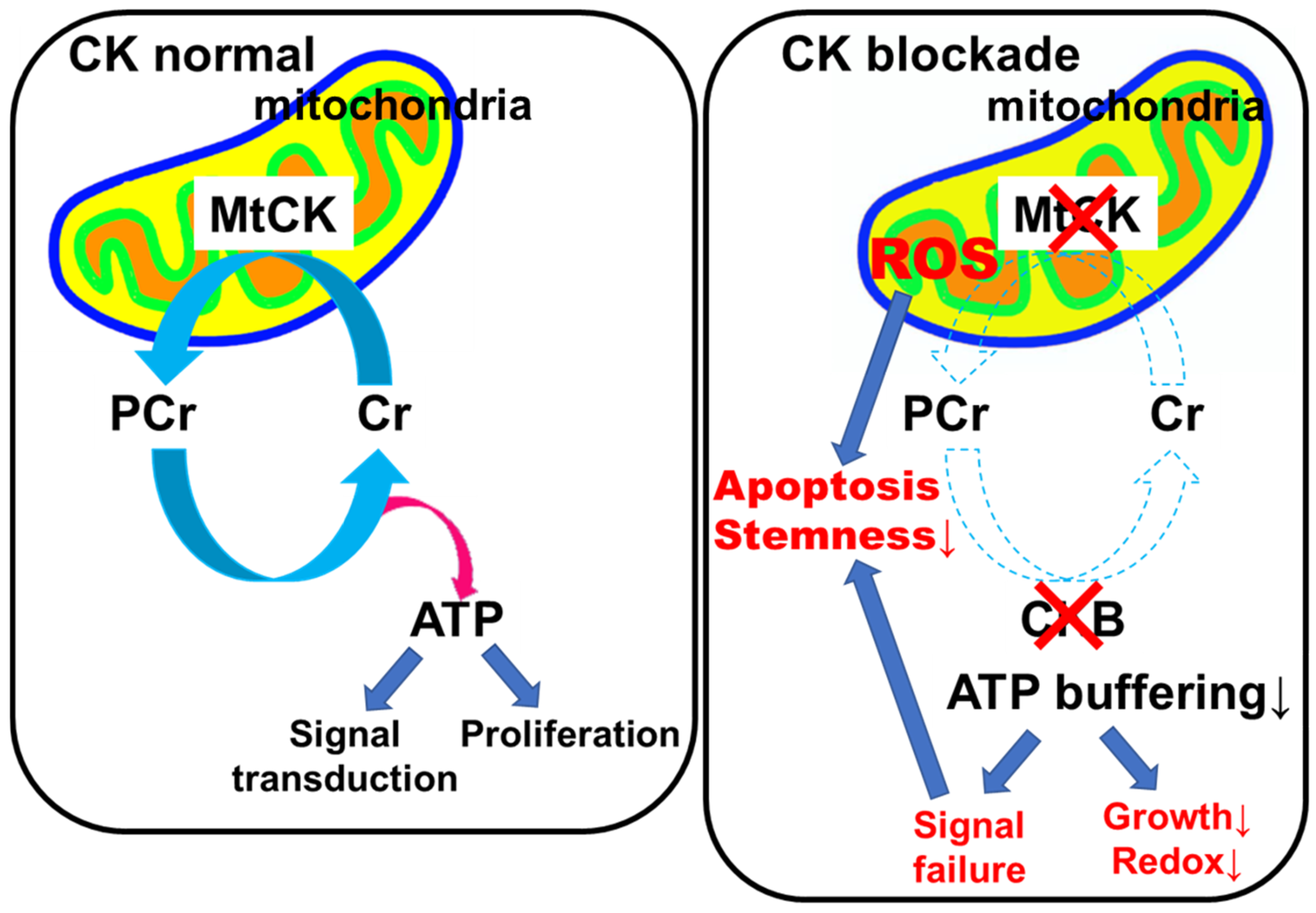

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

4.2. Cell Viability Assay

4.3. Cell Death and Apoptosis

4.4. Cytoimmunochemistry

4.5. Cell Death Rescue Assay

4.6. Sphere Formation Assay

4.7. Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

4.8. Mitochondrial Imaging

4.9. Protein Extraction

4.10. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

4.11. Phosphorylated Protein Profiling

4.12. Immunoblot Analysis

4.13. Knockdown Assay

4.14. Animals

4.15. Animal Tumor Models

4.16. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CK | creatinine kinase |

| CKB | creatinine kinase |

| MTCK | mitochondrial creatinine kinase |

| DNFB | dinitrofluorobenzene |

| OS | osteosarcoma |

| pCr | phosphocreatine |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| CyC | cyclocreatine |

| KD | knockdown |

| VDAC | voltage-dependent anion channel |

| oct3 | POU Class 5 Homeobox 1 |

| pS | Phosphoserine |

| pT | Phosphothereonine |

| pY | phosphotyrosine |

| si | small interfering RNA |

| siC | negative control siRNA |

| AMPKα1 | 5′-AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Catalytic Subunit Alpha-1 |

| PKM2 | pyruvate kinase M2 |

| PFKFB2 | 6-Phosphofructo-2-Kinase/Fructose-2,6-Bisphosphatase 2 |

| NADPH | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| ATP | adenosine triphosphate |

| 4HNE | 4-hydroxynonenal |

| GSH | glutathione |

References

- Ritter, J.; Bielack, S.S. Osteosarcoma. Ann. Oncol. 2010, 21 (Suppl. 7), vii320–vii325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, A. Osteosarcoma: Old and New Challenges. Surg. Pathol. Clin. 2021, 14, 567–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, S.J.; Frezza, A.M.; Abecassis, N.; Bajpai, J.; Bauer, S.; Biagini, R.; Bielack, S.; Blay, J.Y.; Bolle, S.; Bonvalot, S.; et al. Bone sarcomas: ESMO-EURACAN-GENTURIS-ERN PaedCan Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 1520–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeland, S.; Bielack, S.S.; Whelan, J.; Bernstein, M.; Hogendoorn, P.; Krailo, M.D.; Gorlick, R.; Janeway, K.A.; Ingleby, F.C.; Anninga, J.; et al. Survival and prognosis with osteosarcoma: Outcomes in more than 2000 patients in the EURAMOS-1 (European and American Osteosarcoma Study) cohort. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 109, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenol, W.H.; Bounds, P.L.; Dang, C.V. Otto Warburg’s contributions to current concepts of cancer metabolism. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonilla, D.A.; Kreider, R.B.; Stout, J.R.; Forero, D.A.; Kerksick, C.M.; Roberts, M.D.; Rawson, E.S. Metabolic Basis of Creatine in Health and Disease: A Bioinformatics-Assisted Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumien, N.; Shetty, R.A.; Gonzales, E.B. Creatine, Creatine Kinase, and Aging. Subcell. Biochem. 2018, 90, 145–168. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.B. Creatine kinase in cell cycle regulation and cancer. Amino Acids 2016, 48, 1775–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, J.M.; Scherl, A.; Nguyen, A.; Man, F.Y.; Weinberg, E.; Zeng, Z.; Saltz, L.; Paty, P.B.; Tavazoie, S.F. Extracellular metabolic energetics can promote cancer progression. Cell 2015, 160, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Chen, H.; Tong, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Tian, C.; Yang, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Cytochalasin Q exerts anti-melanoma effect by inhibiting creatine kinase B. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2022, 441, 115971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chen, Y.; Gibson, S.B. Starvation-induced autophagy is regulated by mitochondrial reactive oxygen species leading to AMPK activation. Cell Signal 2013, 25, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Hulsurkar, M.; Zhuo, L.; Xu, J.; Yang, H.; Naderinezhad, S.; Wang, L.; Zhang, G.; Ai, N.; Li, L.; et al. CKB inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition and prostate cancer progression by sequestering and inhibiting AKT activation. Neoplasia 2021, 23, 1147–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y. Three-dimensional network of creatine metabolism: From intracellular energy shuttle to systemic metabolic regulatory switch. Mol. Metab. 2025, 100, 102228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlattner, U.; Kay, L.; Tokarska-Schlattner, M. Mitochondrial Proteolipid Complexes of Creatine Kinase. Subcell. Biochem. 2018, 87, 365–408. [Google Scholar]

- Datler, C.; Pazarentzos, E.; Mahul-Mellier, A.L.; Chaisaklert, W.; Hwang, M.S.; Osborne, F.; Grimm, S. CKMT1 regulates the mitochondrial permeability transition pore in a process that provides evidence for alternative forms of the complex. J. Cell Sci. 2014, 127 Pt 8, 1816–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallimann, T.; Tokarska-Schlattner, M.; Schlattner, U. The creatine kinase system and pleiotropic effects of creatine. Amino Acids 2011, 40, 1271–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béard, E.; Braissant, O. Synthesis and transport of creatine in the CNS: Importance for cerebral functions. J. Neurochem. 2010, 115, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmer, W.; Wallimann, T. Functional aspects of creatine kinase in brain. Dev. Neurosci. 1993, 15, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Ford, C.A.; Rodgers, L.; Rushworth, L.K.; Fleming, J.; Mui, E.; Zhang, T.; Watson, D.; Lynch, V.; Mackay, G.; et al. Cyclocreatine Suppresses Creatine Metabolism and Impairs Prostate Cancer Progression. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 2565–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.J.; Winslow, E.R.; Kaddurah-Daouk, R. Cell cycle studies of cyclocreatine, a new anticancer agent. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 5160–5165. [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen, C.A.; Askenasy, N.; Jain, R.K.; Koretsky, A.P. Creatine and cyclocreatine treatment of human colon adenocarcinoma xenografts: 31P and 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopic studies. Br. J. Cancer 1999, 79, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohira, Y.; Inoue, N. Effects of creatine and beta-guanidinopropionic acid on the growth of Ehrlich ascites tumor cells: Ip injection and culture study. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1995, 1243, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kita, M.; Fujiwara-Tani, R.; Kishi, S.; Mori, S.; Ohmori, H.; Nakashima, C.; Goto, K.; Sasaki, T.; Fujii, K.; Kawahara, I.; et al. Role of creatine shuttle in colorectal cancer cells. Oncotarget 2023, 14, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darabedian, N.; Ji, W.; Fan, M.; Lin, S.; Seo, H.S.; Vinogradova, E.V.; Yaron, T.M.; Mills, E.L.; Xiao, H.; Senkane, K.; et al. Depletion of creatine phosphagen energetics with a covalent creatine kinase inhibitor. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2023, 19, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, J.L.; Geng, Y.; Billingham, L.K.; Sadagopan, N.S.; DeLay, S.L.; Subbiah, J.; Chia, T.Y.; McManus, G.; Wei, C.; Wang, H.; et al. A covalent creatine kinase inhibitor ablates glioblastoma migration and sensitizes tumors to oxidative stress. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Franco, A.; Ambrosio, G.; Baroncelli, L.; Pizzorusso, T.; Barison, A.; Olivotto, I.; Recchia, F.A.; Lombardi, C.M.; Metra, M.; Ferrari Chen, Y.F.; et al. Creatine deficiency and heart failure. Heart Fail. Rev. 2022, 27, 1605–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; To, K.K.W. Serum creatine kinase elevation following tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment in cancer patients: Symptoms, mechanism, and clinical management. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2024, 17, e70053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.Z.; Pan, G.Q.; Xiong, C.; Ding, Z.N.; Zhang, T.S.; Yan, L.J.; Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Dong, X.F.; Yan, Y.C.; et al. Hypoxia-Induced Creatine Uptake Reprograms Metabolism to Antagonize PARP1-Mediated Cell Death and Facilitate Tumor Progression in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2025, 85, 3671–3688, Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldve, R.E.; Fischer, S.M. Tumor-promoting activity of 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene. Int. J. Cancer 1995, 60, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; DeLay, S.L.; Chen, X.; Miska, J. It Is Not Just About Storing Energy: The Multifaceted Role of Creatine Metabolism on Cancer Biology and Immunology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sömjen, D.; Kaye, A.M. Stimulation by insulin-like growth factor-I of creatine kinase activity in skeletal-derived cells and tissues of male and female rats. J. Endocrinol. 1994, 143, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Bu, P. The two sides of creatine in cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2022, 32, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, L.E.; Machado, L.B.; Santiago, A.P.; da-Silva, W.S.; De Felice, F.G.; Holub, O.; Oliveira, M.F.; Galina, A. Mitochondrial creatine kinase activity prevents reactive oxygen species generation: Antioxidant role of mitochondrial kinase-dependent ADP re-cycling activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 37361–37371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, X.; Fu, R. Construction of a 5-gene prognostic signature based on oxidative stress related genes for predicting prognosis in osteosarcoma. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0295364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemeshko, V.V. VDAC electronics: 3. VDAC-Creatine kinase-dependent generation of the outer membrane potential in respiring mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1858, 1411–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordin, L.; Vargiu, C.; Clari, G.; Brunati, A.M.; Colombatto, S.; Salvi, M.; Grillo, M.A.; Toninello, A. Phosphorylation of recombinant human spermidine/spermine N(1)-acetyltransferase by CK1 and modulation of its binding to mitochondria: A comparison with CK2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 290, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.M.; Sies, H.; Park, E.M.; Thomas, J.A. Phosphorylase and creatine kinase modification by thiol-disulfide exchange and by xanthine oxidase-initiated S-thiolation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1990, 276, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Y.; Li, Q.; Liu, B.; Wang, D.; Liu, Z.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Zang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wen, Y.; et al. Ubiquitous mitochondrial creatine kinase promotes the progression of gastric cancer through a JNK-MAPK/JUN/HK2 axis regulated glycolysis. Gastric Cancer 2023, 26, 69–81, Erratum in Gastric Cancer 2024, 27, 646–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.J.; Chen, C.P.; Lee, Y.S.; Ng, P.S.; Chang, G.D.; Pao, Y.H.; Lo, H.F.; Peng, C.H.; Cheong, M.L.; Chen, H. Functional antagonism between ΔNp63α and GCM1 regulates human trophoblast stemness and differentiation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Qi, Q.; Jiang, X.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Cai, Y.; Ran, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.; et al. Phosphocreatine Promotes Epigenetic Reprogramming to Facilitate Glioblastoma Growth Through Stabilizing BRD2. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14, 1547–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, W.J.; Christofk, H.R. The metabolic milieu of metastases. Cell 2015, 160, 363–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, M.; Zhang, J.; Wicha, M.S.; Luo, M. Redox regulation of cancer stem cells: Biology and therapeutic implications. Med. Comm. Oncol. 2024, 3, e70005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokumura, K.; Fukasawa, K.; Ichikawa, J.; Sadamori, K.; Hiraiwa, M.; Hinoi, E. PDK1-dependent metabolic reprogramming regulates stemness and tumorigenicity of osteosarcoma stem cells through ATF3. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisen, H.N.; Belmam, S. Studies of hypersensitivity to low molecular weight substances. II. Reactions of some allergenic substituted dinitrobenzenes with cysteine or cystine of skin proteins. J. Exp. Med. 1953, 98, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; He, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Aziz, F.; Yang, M.; Zhu, X. Demethylzeylasteral inhibits osteosarcoma cell proliferation by regulating METTL17-mediated mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2025, 499, 117348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wang, Q.; Chen, J.; Cai, G.; Zhang, Z.; Zou, H.; Zou, J.X.; Liu, Q.; Ji, S.; Shao, G.; et al. Tumor mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation stimulated by the nuclear receptor RORγ represents an effective therapeutic opportunity in osteosarcoma. Cell Rep. Med. 2024, 5, 101519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, T.A.; Ahnert, J.R.; Piha-Paul, S.A.; Fu, S.; Janku, F.; Karp, D.D.; Naing, A.; Dumbrava, E.E.I.; Pant, S.; Subbiah, V.; et al. Phase I trial of IACS-010759 (IACS), a potent, selective inhibitor of complex I of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewell, B.E.; Xu, A.; Zhu, D.; Huang, M.F.; Lu, L.; Liu, M.; Underwood, E.L.; Park, J.H.; Fan, H.; Gingold, J.A.; et al. Patient-derived iPSCs link elevated mitochondrial respiratory complex I function to osteosarcoma in Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. PLoS Genet. 2021, 17, e1009971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Dou, X.; Li, C. CKB affects human osteosarcoma progression by regulating the p53 pathway. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2022, 12, 4652–4665. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Lyu, P.; Andreev, D.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, F.; Bozec, A. Hypoxia-immune-related microenvironment prognostic signature for osteosarcoma. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 974851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, I.; Yamaguchi, N.; Andreu-Agullo, C.; Tian, H.S.; Sridhar, S.; Takeda, S.; Gonsalves, F.C.; Loo, J.M.; Barlas, A.; Manova-Todorova, K.; et al. Therapeutic targeting of SLC6A8 creatine transporter suppresses colon cancer progression and modulates human creatine levels. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabi7511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.J.; Chen, S.F.; Clark, G.M.; Degen, D.; Wajima, M.; Von Hoff, D.D.; Kaddurah-Daouk, R. Evaluation of creatine analogues as a new class of anticancer agents using freshly explanted human tumor cells. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1994, 86, 608–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuniyasu, H.; Oue, N.; Wakikawa, A.; Shigeishi, H.; Matsutani, N.; Kuraoka, K.; Ito, R.; Yokozaki, H.; Yasui, W. Expression of receptors for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE) is closely associated with the invasive and metastatic activity of gastric cancer. J. Pathol. 2002, 196, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PCR Primers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | ID | Forward | Reverse |

| human Oct3 | BC117437.1 | gaaggatgtggtccgagtgt | gtgaagtgagggctcccata |

| human nestin | NM_006617.1 | aacagcgacggaggtctcta | ttctcttgtcccgcagactt |

| human CKB | NM_001823.4 | catatcaagctgcccaacct | accagctccacctctgagaa |

| human mtCK | J05401.1 | gccgctactacaagctgtcc | cctggtgtgatcctcctcat |

| human ALPL | AH005272.2 | ccagggaaatctgtgggcat | ccctaccttccaccagcaag |

| Antibody (clone) | Cat No. | Company | |

| pS (A4A) | 05-1000 | Merck, Darmstadt, Germany | |

| pT (PTR-8) | P6623 | Merck, Darmstadt, Germany | |

| pY (4G10) | 05-1050 | Merck, Darmstadt, Germany | |

| human CKB | 18713-1-AP | Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA | |

| human MtCK1 | 15346-1-AP | Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA | |

| human MtCK2 | 13207-1-AP | Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA | |

| human β-actin | JAN4548995073129 | Fuji Film WAKO, Osaka, Japan | |

| human AKT | #9272 | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA | |

| human pAKT, Ser473 (D9E) | #11861 | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA | |

| human ERKp42 | #9108 | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA | |

| human pERKp42, Tyr204 (E4) | sc-7383 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA | |

| human STAT3 (124H6) | #2217 | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA | |

| human pSTAT3, Tyr705 (B7) | sc-8059 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA | |

| human Ki67 | ab15580 | Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA | |

| Small interfering RNA | Cat No. | Company | |

| siC (Stealth RNAi) | 12935-300 | Thermo Fisher, Tokyo, Japan | |

| siCKM | abx901083 | Abbexa, Cambridge, UK | |

| siMTCK1 | abx911914 | Abbexa, Cambridge, UK | |

| siMTCK2 | abx911918 | Abbexa, Cambridge, UK | |

| ELISA | |||

| Target | Cat No. | Company | |

| human AMPK | MBS2514316 | MyBioSource, San Diego, CA, USA | |

| human PKM2 | NBP3-18036 | Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO, USA | |

| human AKT1/2/3 | ab253299 | Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA | |

| human PFK2 | #SG-00103 | Sinogeneclon, Hangzhou, China | |

| CK activity | MAK116 | Merck, Darmstadt, Germany | |

| mouse Ki-67 | #14507 | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA | |

| ATP | ab83355 | Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA | |

| NADPH | ABIN771004 | antibodies-online, Limerick, PA, USA | |

| 4HNE | ab287803 | Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA | |

| GSH | CEA294Ge | CLOUD-CLONE, Wuhan, China | |

| pCr | ELK8254 | ELK Biotechnology, Sugar Land, TX, USA | |

| Lactate | ab65331 | Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kishi, S.; Sasaki, R.; Fujiwara-Tani, R.; Ohmori, H.; Luo, Y.; Fujii, K.; Sasaki, T.; Goto, K.; Miyagawa, Y.; Kawahara, I.; et al. Creatine Kinase Blockade Disrupts Energy Metabolism and Redox Homeostasis to Suppress Osteosarcoma Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11555. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311555

Kishi S, Sasaki R, Fujiwara-Tani R, Ohmori H, Luo Y, Fujii K, Sasaki T, Goto K, Miyagawa Y, Kawahara I, et al. Creatine Kinase Blockade Disrupts Energy Metabolism and Redox Homeostasis to Suppress Osteosarcoma Progression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11555. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311555

Chicago/Turabian StyleKishi, Shingo, Rika Sasaki, Rina Fujiwara-Tani, Hitoshi Ohmori, Yi Luo, Kiyomu Fujii, Takamitsu Sasaki, Kei Goto, Yoshihiro Miyagawa, Isao Kawahara, and et al. 2025. "Creatine Kinase Blockade Disrupts Energy Metabolism and Redox Homeostasis to Suppress Osteosarcoma Progression" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11555. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311555

APA StyleKishi, S., Sasaki, R., Fujiwara-Tani, R., Ohmori, H., Luo, Y., Fujii, K., Sasaki, T., Goto, K., Miyagawa, Y., Kawahara, I., Nishida, R., Nukaga, S., Nishiguchi, Y., Ogata, R., Honoki, K., & Kuniyasu, H. (2025). Creatine Kinase Blockade Disrupts Energy Metabolism and Redox Homeostasis to Suppress Osteosarcoma Progression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11555. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311555