Eco-Friendly Fabrication of Secretome-Loaded, Glutathione-Extended Waterborne Polyurethane Nanofibers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

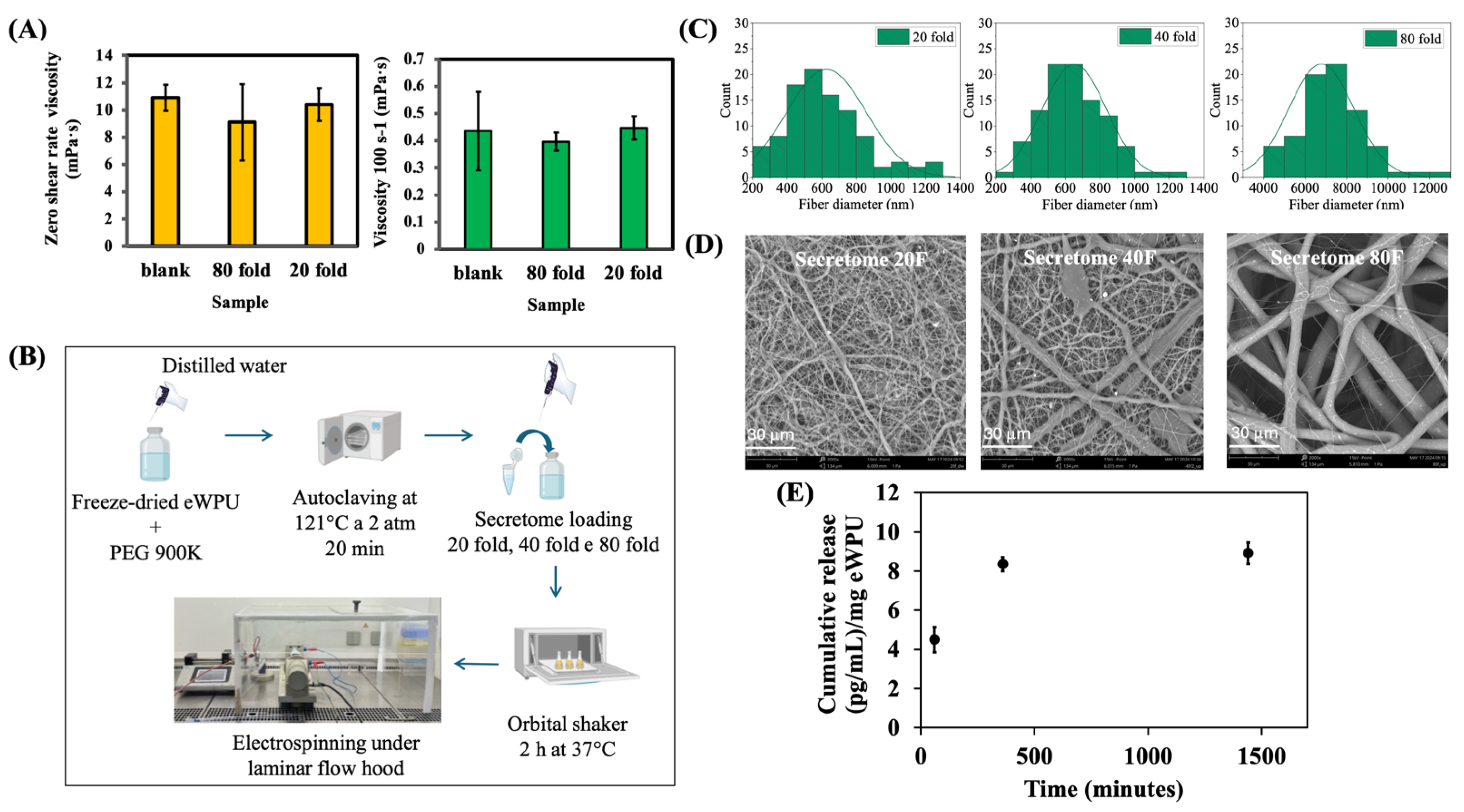

2.1. Optimization of Electrospinning Parameters for WPU Dispersions

2.2. In Vitro Cytocompatibility Test

2.3. Secretome Loading and in Vitro Release

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Apparatus

3.3. Synthesis of GSSG-Extended WPU Urea Derivatives

3.4. Fabrication of WPU-Based Nanofibers by Electrospinning and Characterization

3.5. In Vitro Cytocompatibility Tests

3.6. Fabrication of Secretome-Loaded Electrospun Membranes

3.7. Secretome Release Study

3.8. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xue, J.; Wu, T.; Dai, Y.; Xia, Y. Electrospinning and Electrospun Nanofibers: Methods, Materials, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 5298–5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, H.; Zhang, M.; Yu, D.G. Electrospun Medicated Nanofibers for Wound Healing: Review. Membranes 2021, 11, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Ouyang, J.; Zhang, L.; Xue, J.; Zhang, H.; Tao, W. Electroactive Electrospun Nanofibers for Tissue Engineering. Nano Today 2021, 39, 101196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Tan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Pan, W.; Tan, G. Stimuli-Responsive Electrospun Nanofibers for Drug Delivery, Cancer Therapy, Wound Dressing, and Tissue Engineering. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, D.; Hsiao, B.S.; Chu, B. Functional Electrospun Nanofibrous Scaffolds for Biomedical Applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2007, 59, 1392–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhou, P.; Mao, Y. Electrospun Nanofibrous Membrane for Biomedical Application. SN Appl. Sci. 2022, 4, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanov, S.; Berlec, A. Electrospun Nanofibers as Carriers of Microorganisms, Stem Cells, Proteins, and Nucleic Acids in Therapeutic and Other Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosoudi, N.; Hasanzadeh, A.; Hart, M.; Weaver, B. Advancements and Future Perspectives in Cell Electrospinning and Bio-Electrospraying. Adv. Biol. 2023, 7, e2300213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caplan, A.I. What’s in a Name? Tissue Eng. Part A 2010, 16, 2415–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, A.I. Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Time to Change the Name! Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2017, 6, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, J.; Patel, T. The Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome as an Acellular Regenerative Therapy for Liver Disease. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 54, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md Fadilah, N.I.; Mohd Abdul Kader Jailani, M.S.; Badrul Hisham, M.A.I.; Sunthar Raj, N.; Shamsuddin, S.A.; Ng, M.H.; Fauzi, M.B.; Maarof, M. Cell Secretomes for Wound Healing and Tissue Regeneration: Next Generation Acellular Based Tissue Engineered Products. J. Tissue Eng. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, F.S.; Calligaris, M.; Calzà, L.; Fiorica, C.; Baldassarro, V.A.; Carreca, A.P.; Lorenzini, L.; Giuliani, A.; Carcione, C.; Cuscino, N.; et al. Topical Application of a Hyaluronic Acid-Based Hydrogel Integrated with Secretome of Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for Diabetic Ulcer Repair. Regen. Ther. 2024, 26, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, D.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Mei, X.; Xu, W.; Cheng, K.; Zhong, B. Nanoparticles Functionalized with Stem Cell Secretome and CXCR4-Overexpressing Endothelial Membrane for Targeted Osteoporosis Therapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanian, M.H.; Mirzadeh, H.; Baharvand, H. In Situ Forming, Cytocompatible, and Self-Recoverable Tough Hydrogels Based on Dual Ionic and Click Cross-Linked Alginate. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 1646–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chwalek, K.; Levental, K.R.; Tsurkan, M.V.; Zieris, A.; Freudenberg, U.; Werner, C. Two-Tier Hydrogel Degradation to Boost Endothelial Cell Morphogenesis. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 9649–9657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, D.; Swindell, H.S.; Ramasubramanian, L.; Liu, R.; Lam, K.S.; Farmer, D.L.; Wang, A. Extracellular Matrix Mimicking Nanofibrous Scaffolds Modified With Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles for Improved Vascularization. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, C.J.; Redondo-Castro, E.; Allan, S.M. The Therapeutic Potential of the Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome in Ischaemic Stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2018, 38, 1276–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirwan, V.P.; Kowalczyk, T.; Bar, J.; Buzgo, M.; Filová, E.; Fahmi, A. Advances in Electrospun Hybrid Nanofibers for Biomedical Applications. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palumbo, F.S.; Fiorica, C.; Paola Carreca, A.; Iannolo, G.; Pitarresi, G.; Amico, G.; Giammona, G.; Conaldi, P.G.; Maria Chinnici, C. Modulating the Release of Bioactive Molecules of Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Secretome: Heparinization of Hyaluronic Acid-Based Hydrogels. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 653, 123904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.; Schirmer, L.; Pinho, T.S.; Atallah, P.; Cibrão, J.R.; Lima, R.; Afonso, J.; B-Antunes, S.; Marques, C.R.; Dourado, J.; et al. Sustained Release of Human Adipose Tissue Stem Cell Secretome from Star-Shaped Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Glycosaminoglycan Hydrogels Promotes Motor Improvements after Complete Transection in Spinal Cord Injury Rat Model. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, e2202803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, J.; Yi, K.; Wang, H.; Wei, H.; Chan, H.F.; Tao, Y.; Li, M. Delivery of Stem Cell Secretome for Therapeutic Applications. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 2009–2030. [Google Scholar]

- Gaetani, M.; Chinnici, C.M.; Carreca, A.P.; Di Pasquale, C.; Amico, G.; Conaldi, P.G. Unbiased and Quantitative Proteomics Reveals Highly Increased Angiogenesis Induction by the Secretome of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Isolated from Fetal Rather than Adult Skin. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2018, 12, e949–e961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Rivera-Bolanos, N.; Jiang, B.; Ameer, G.A. Advanced Functional Biomaterials for Stem Cell Delivery in Regenerative Engineering and Medicine. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1809009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R.; Mndlovu, H.; Kumar, P.; Adeyemi, S.A.; Choonara, Y.E. Cell Secretome Strategies for Controlled Drug Delivery and Wound-Healing Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria-Echart, A.; Fernandes, I.; Barreiro, F.; Corcuera, M.A.; Eceiza, A. Advances in Waterborne Polyurethane and Polyurethane-Urea Dispersions and Their Eco-Friendly Derivatives: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancilla, F.; Martorana, A.; Fiorica, C.; Pitarresi, G.; Giammona, G.; Palumbo, F.S. Glutathione-Integrated Waterborne Polyurethanes: Aqueous Dispersible, Redox-Responsive Biomaterials for Cancer Drug Delivery. Eur. Polym. J. 2025, 226, 113759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Mahanwar, P. A Brief Discussion on Advances in Polyurethane Applications. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2020, 3, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosheeladevi, P.P.; Tuan Noor Maznee, T.I.; Hoong, S.S.; Nurul ‘Ain, H.; Mohd Norhisham, S.; Norhayati, M.N.; Srihanum, A.; Yeong, S.K.; Hazimah, A.H.; Sendijarevic, V.; et al. Performance of Palm Oil-Based Dihydroxystearic Acid as Ionizable Molecule in Waterborne Polyurethane Dispersions. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133, 43614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankoti, K.; Rameshbabu, A.P.; Datta, S.; Maity, P.P.; Goswami, P.; Datta, P.; Ghosh, S.K.; Mitra, A.; Dhara, S. Accelerated Healing of Full Thickness Dermal Wounds by Macroporous Waterborne Polyurethane-Chitosan Hydrogel Scaffolds. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 81, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Hu, J.; Ou, Y.; He, X.; Wang, Y.; Zou, C.; Jiang, Y.; Luo, F.; Lu, D.; Li, Z.; et al. Shape-Recoverable Hyaluronic Acid-Waterborne Polyurethane Hybrid Cryogel Accelerates Hemostasis and Wound Healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 17093–17108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, A.K.; Wicks, D.A.; Madbouly, S.A.; Otaigbe, J.U. Effect of Ionic Content, Solid Content, Degree of Neutralization, and Chain Extension on Aqueous Polyurethane Dispersions Prepared by Prepolymer Method. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2005, 98, 2514–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Xie, Y.; Wang, L.; Yang, L.; Yu, J.; Miyamoto, A.; Sun, F. Development of FGF-2-Loaded Electrospun Waterborne Polyurethane Fibrous Membranes for Bone Regeneration. Regen. Biomater. 2021, 8, rbaa046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miceli, G.C.; Martorana, A.; Cancilla, F.; Pitarresi, G.; Licciardi, M.; Palumbo, F.S. Synthesis, Characterization, and Processing of Highly Bioadhesive Polyurethane Urea as a Microfibrous Scaffold Inspired by Mussels. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 8483–8494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federico, S.; Martorana, A.; Pitarresi, G.; Palumbo, F.S.; Fiorica, C.; Giammona, G. Development of Stimulus-Sensitive Electrospun Membranes Based on Novel Biodegradable Segmented Polyurethane as Triggered Delivery System for Doxorubicin. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 136, 212769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martorana, A.; Fiorica, C.; Palumbo, F.S.; Federico, S.; Giammona, G.; Pitarresi, G. Redox Responsive 3D-Printed Nanocomposite Polyurethane-Urea Scaffold for Doxorubicin Local Delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 88, 104890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, F.S.; Federico, S.; Pitarresi, G.; Fiorica, C.; Giammona, G. Synthesis and Characterization of Redox-Sensitive Polyurethanes Based on L-Glutathione Oxidized and Poly(Ether Ester) Triblock Copolymers. React. Funct. Polym. 2021, 166, 104986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorana, A.; Puleo, G.; Miceli, G.C.; Cancilla, F.; Licciardi, M.; Pitarresi, G.; Tranchina, L.; Marrale, M.; Palumbo, F.S. Redox/NIR Dual-Responsive Glutathione Extended Polyurethane Urea Electrospun Membranes for Synergistic Chemo-Photothermal Therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 669, 125108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Toftdal, M.S.; Le Friec, A.; Dong, M.; Han, X.; Chen, M. 3D Electrospun Synthetic Extracellular Matrix for Tissue Regeneration. Small Sci. 2021, 1, 2100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avossa, J.; Herwig, G.; Toncelli, C.; Itel, F.; Rossi, R.M. Electrospinning Based on Benign Solvents: Current Definitions, Implications and Strategies. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 2347–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Mo, X.; Wu, T. Progress in Electrospun Fibers for Manipulating Cell Behaviors. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2023, 5, 1241–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, B.; Schlatter, G.; Hébraud, P.; Mouillard, F.; Chehma, L.; Hébraud, A.; Lobry, E. Green Electrospinning of Highly Concentrated Polyurethane Suspensions in Water: From the Rheology to the Fiber Morphology. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2024, 309, 2400157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodero, A.; Castellano, M.; Vicini, S.; Hébraud, A.; Lobry, E.; Nhut, J.M.; Schlatter, G. Eco-Friendly Needleless Electrospinning and Tannic Acid Functionalization of Polyurethane Nanofibers with Tunable Wettability and Mechanical Performances. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2022, 307, 2100823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beycan, B.; Kalkan Erdoğan, M.; Sancak, E.; Karakışla, M.; Saçak, M. Creating Safe, Biodegradable Nanofibers for Food Protection: A Look into Waterborne Polyurethane Electrospinning. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 14495–14507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buruaga, L.; Sardon, H.; Irusta, L.; González, A.; Fernández-Berridi, M.J.; Iruin, J.J. Electrospinning of Waterborne Polyurethanes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010, 115, 1176–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| WPU | PCL-PEG-PCL/DMPA/IPDI/GSSG Molar Ratio | mg GSSG/gWPU | mg COOH/gWPU |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.00 | 1/1/3.5/1.5 | 76.45 ± 3.80 | 17.96 ± 0.41 |

| 0.75 | 0.75/1.25/3.5/1.5 | 72.45 ± 5.02 | 30.10 ± 0.27 |

| 0.50 | 0.5/1.5/3.5/1.5 | 66.30 ± 4.53 | 41.87 ± 0.55 |

| Sample Name | WPU-GSSG 0.75 [% w/w] | PEO [% w/w] | Q (mL/min) | V (kV) | d (cm) | Fiber Morphology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12.8 | 2.12 | 0.008 | 20 | 15 | Bead on a string |

| 2 | 16.83 | 0.58 | / | 20 | 15 | Non-uniform fiber |

| 3 | 19.5 | 0.64 | / | 20 | 15 | Non-uniform fiber |

| 4 | 22.9 | 0.76 | 0.008 | 20 | 15 | Non-uniform fiber |

| 5 | 22.9 | 0.76 | 0.02 | 20 | 15 | Bead on a string |

| 6 | 28.46 | 0.92 | / | 20 | 15 | Bead on a string |

| 7 | 22.73 | 1.52 | 0.02 | 28.5 | 15 | Non-uniform fiber |

| 8 | 22.73 | 1.52 | 0.02 | 28.5 | 20 | Non-uniform fiber |

| 9 | 22.5 | 2.26 | 0.01 | 30 | 30 | Bead-free fiber |

| 10 | 22.5 | 2.26 | 0.01 | 22 | 20 | Bead-free fiber |

| 11 | 22.5 | 2.26 | 0.008 | 20 | 30 | Bead-free fiber |

| 12 | 22.5 | 2.26 | 0.01 | 25 | 25 | Bead-free fiber |

| 13 | 22.5 | 2.26 | 0.02 | 25 | 25 | Bead-free fiber |

| 14 | 22.5 | 2.26 | 0.01 | 30 | 20 | Bead-free fiber |

| 15 | 22.5 | 2.26 | 0.028 | 22 | 25 | Bead-free fiber |

| 16 | 22.5 | 2.26 | 0.015–0.03 | 20 | 25 | Bead-free fiber |

| Sample Name | WPU-GSSG 0.5 [% w/w] | PEO [% w/w] | Q (mL/min) | V (kV) | d (cm) | Fiber Morphology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 27.78 | 2.78 | / | / | / | Non-uniform fiber |

| 2 | 22.56 | 2.26 | / | / | / | Non-uniform fiber |

| 3 | 19.61 | 1.96 | 25 | 25 | 24 | Non-uniform fiber |

| 4 | 20.82 | 2.08 | 25 | 25 | 20 | Bead on a string |

| 5 | 22.5 | 2.26 | 20–25 | 20–25 | 20–23 | Bead-free fiber |

| 6 | 22.5 | 2.26 | 22.5 | 22.5 | 25 | Bead-free fiber |

| 7 | 22.5 | 2.26 | 23 | 23 | 25 | Bead-free fiber |

| 8 | 22.5 | 2.26 | 18–20 | 18–20 | 20 | Bead-free fiber |

| 9 | 22.5 | 2.26 | 19 | 19 | 15 | Bead-free fiber |

| 10 | 22.5 | 2.26 | 23 | 23 | 20 | Bead-free fiber |

| 11 | 22.5 | 2.26 | 23 | 23 | 20 | Bead-free fiber |

| Sample Name | WPU-GSSG 1 [% w/w] | PEO [% w/w] | Q (mL/min) | V (kV) | d (cm) | Fiber Morphology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16.39 | 1.64 | 0.03 | 27 | 20 | Bead on a string |

| Sample Name | WPU-GSSG0.5 [% w/w] | PEO [% w/w] | Q (mL/min) | V (kV) | d (cm) | Fiber Morphology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eWPU-GSSG0.5/PEO | 22.5 | 2.26 | 0.02 | 22.5 | 25 | Bead-free fiber |

| eWPU-GSSG0.75/PEO | 22.5 | 2.26 | 0.028 | 22 | 25 | Bead-free fiber |

| eWPU-GSSG1.0/PEO | 16.39 | 1.69 | 0.03 | 27 | 20 | Bead on a string |

| Sample Name | WPU [% w/w] | PEO [% w/w] | Q (mL/min) | V (kV) | d (cm) | Fiber Morphology | Fiber Diameter (µm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eWPU-GSSG0.5/PEO 20 fold | 22.5 | 2.26 | 0.01 | 23 | 10−15 | Bead-free fiber | 0.658 ± 258.58 |

| eWPU-GSSG0.5/PEO 40 fold | 22.5 | 2.26 | 0.01 | 25 | 17 | Bead-free fiber | 6.41 ± 2.97 × 103 |

| eWPU-GSSG0.5/PEO 80 fold | 22.5 | 2.26 | 0.01 | 26 | 20 | Bead-free fiber | 6.78 ± 1.56 × 103 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Accardo, P.; Cancilla, F.; Martorana, A.; Calascibetta, F.; Amico, G.; Pitarresi, G.; Fiorica, C.; Chinnici, C.M.; Palumbo, F.S. Eco-Friendly Fabrication of Secretome-Loaded, Glutathione-Extended Waterborne Polyurethane Nanofibers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11556. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311556

Accardo P, Cancilla F, Martorana A, Calascibetta F, Amico G, Pitarresi G, Fiorica C, Chinnici CM, Palumbo FS. Eco-Friendly Fabrication of Secretome-Loaded, Glutathione-Extended Waterborne Polyurethane Nanofibers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11556. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311556

Chicago/Turabian StyleAccardo, Paolo, Francesco Cancilla, Annalisa Martorana, Filippo Calascibetta, Giandomenico Amico, Giovanna Pitarresi, Calogero Fiorica, Cinzia Maria Chinnici, and Fabio Salvatore Palumbo. 2025. "Eco-Friendly Fabrication of Secretome-Loaded, Glutathione-Extended Waterborne Polyurethane Nanofibers" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11556. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311556

APA StyleAccardo, P., Cancilla, F., Martorana, A., Calascibetta, F., Amico, G., Pitarresi, G., Fiorica, C., Chinnici, C. M., & Palumbo, F. S. (2025). Eco-Friendly Fabrication of Secretome-Loaded, Glutathione-Extended Waterborne Polyurethane Nanofibers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11556. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311556