Maternal Gestational Diabetes Impairs Fetoplacental Insulin-Induced Vasodilation via AKT/eNOS Pathway and Reduces Placental Efficiency

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

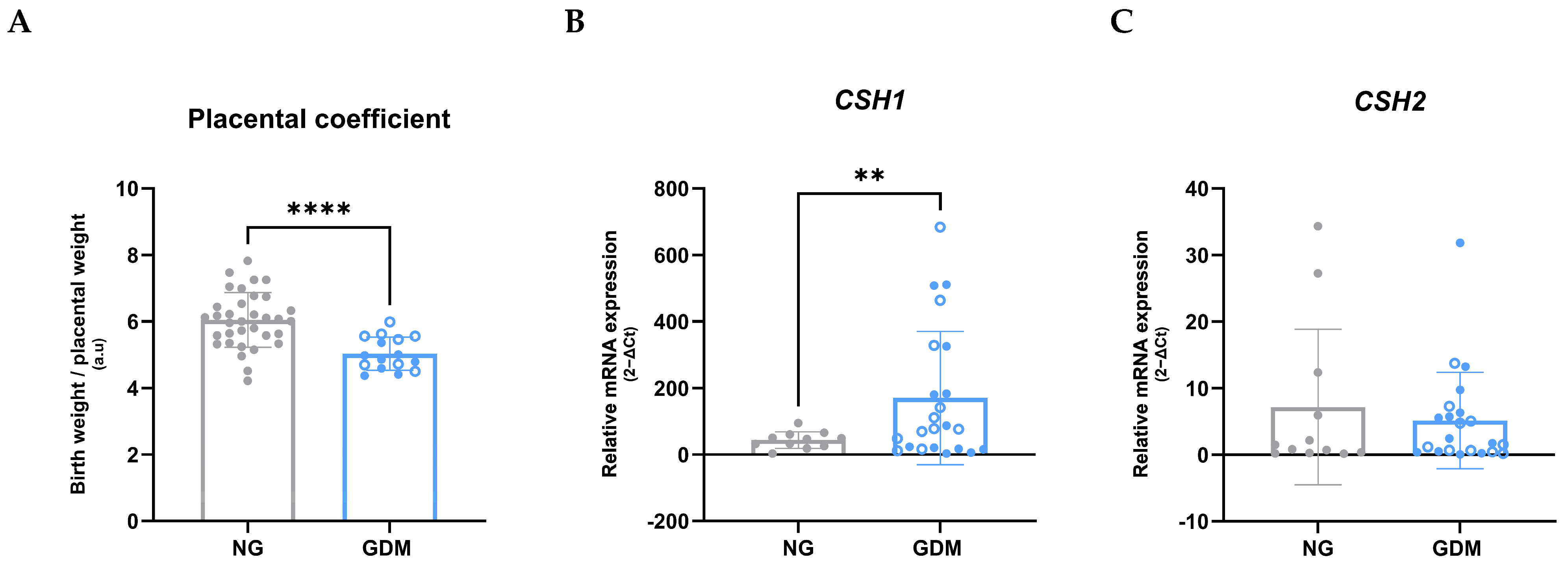

2.1. Maternal, Neonatal, and Placental Outcomes Associated with GDM

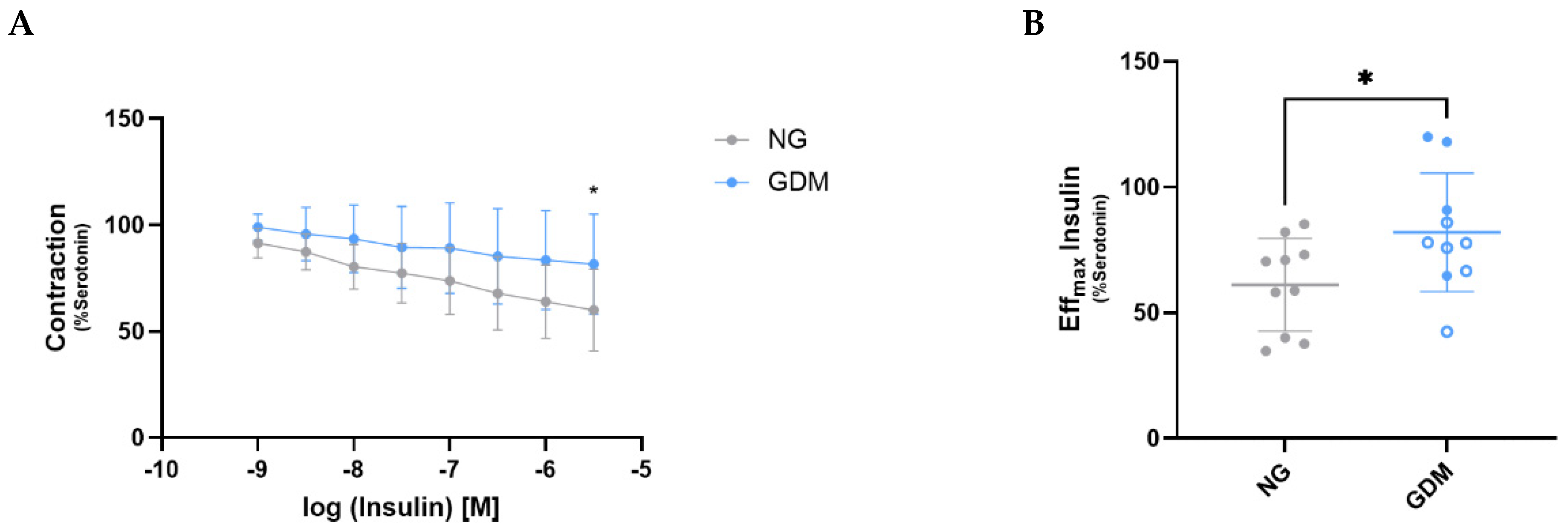

2.2. GDM Impairs Insulin-Mediated Vasodilation in Fetoplacental Vessels

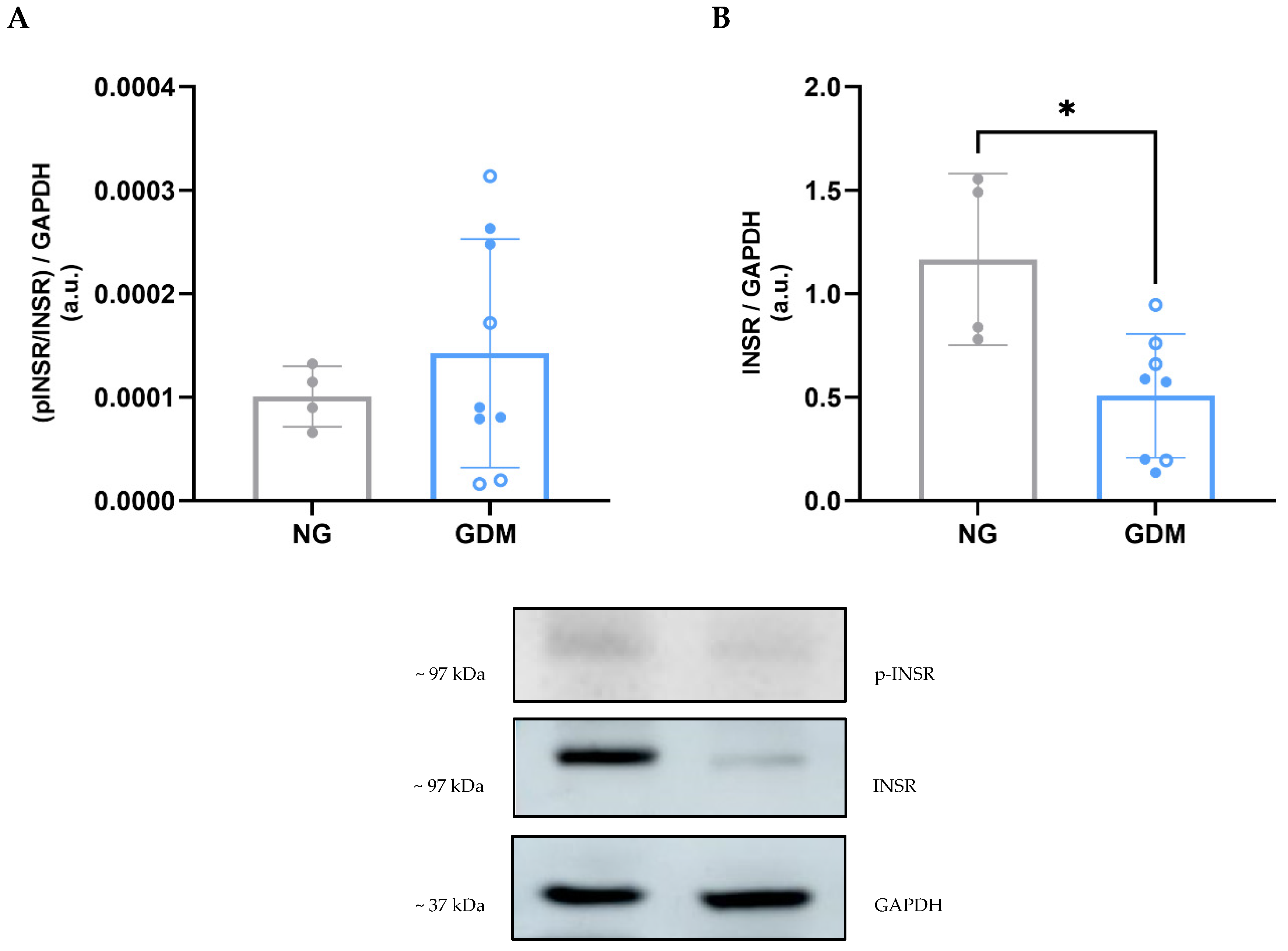

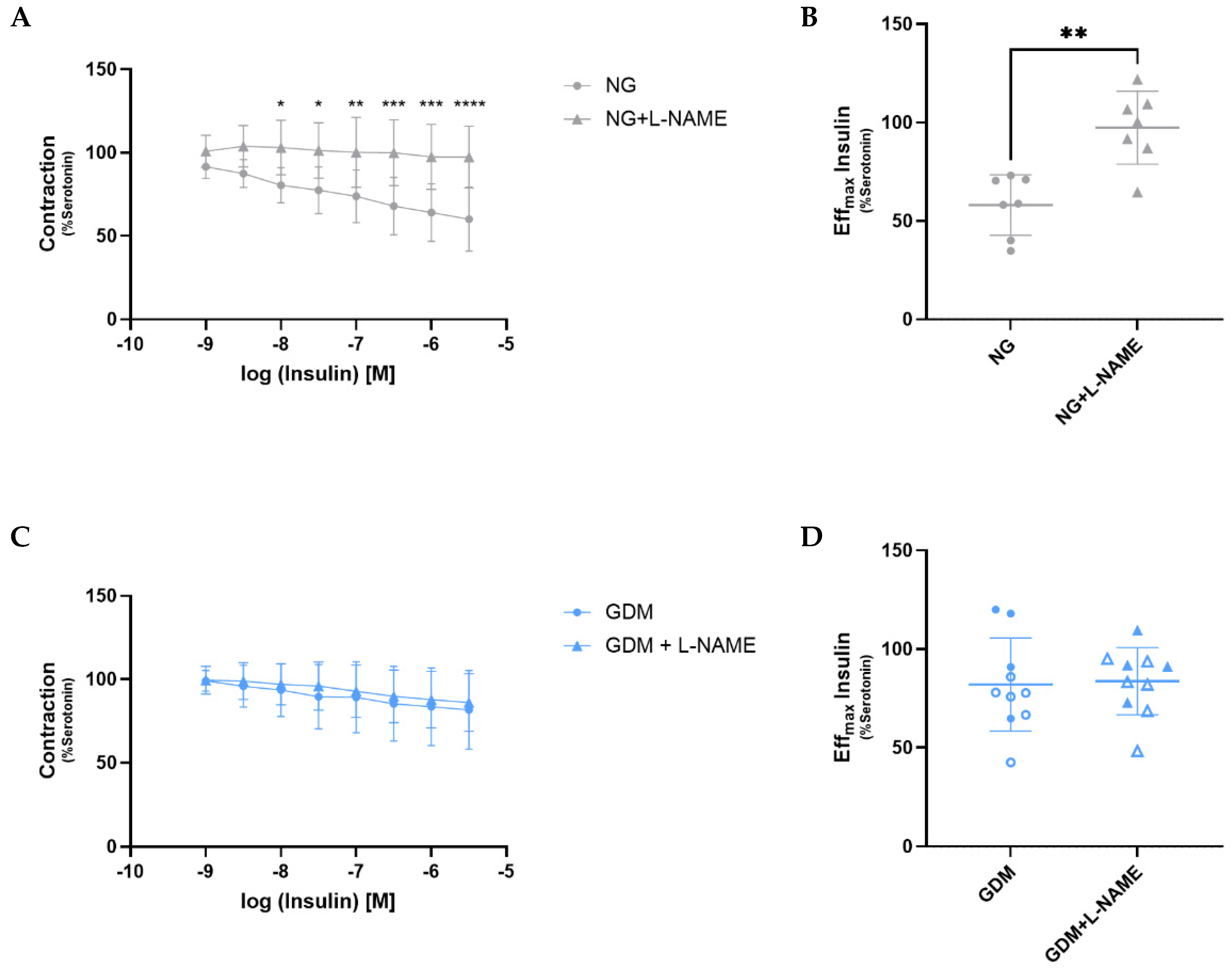

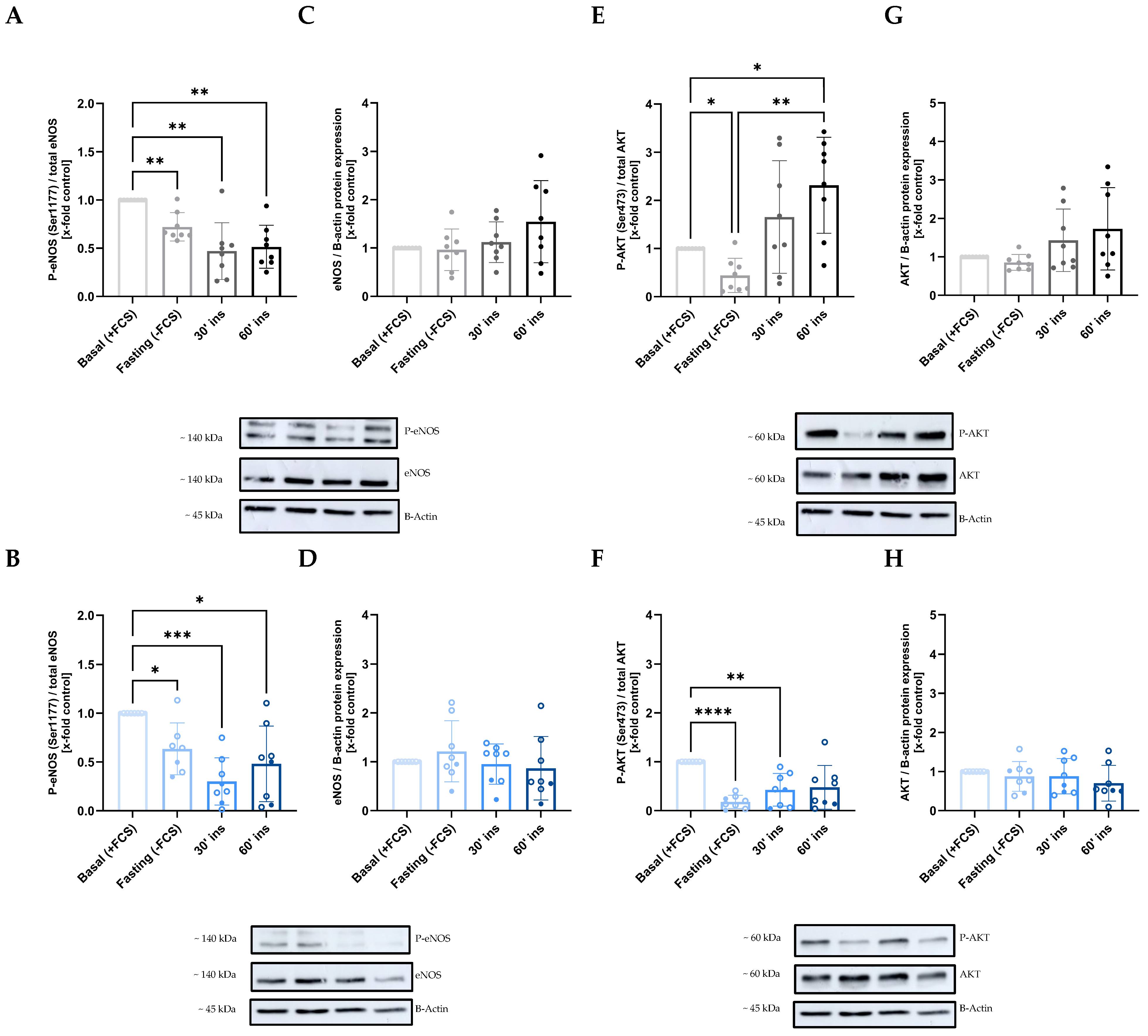

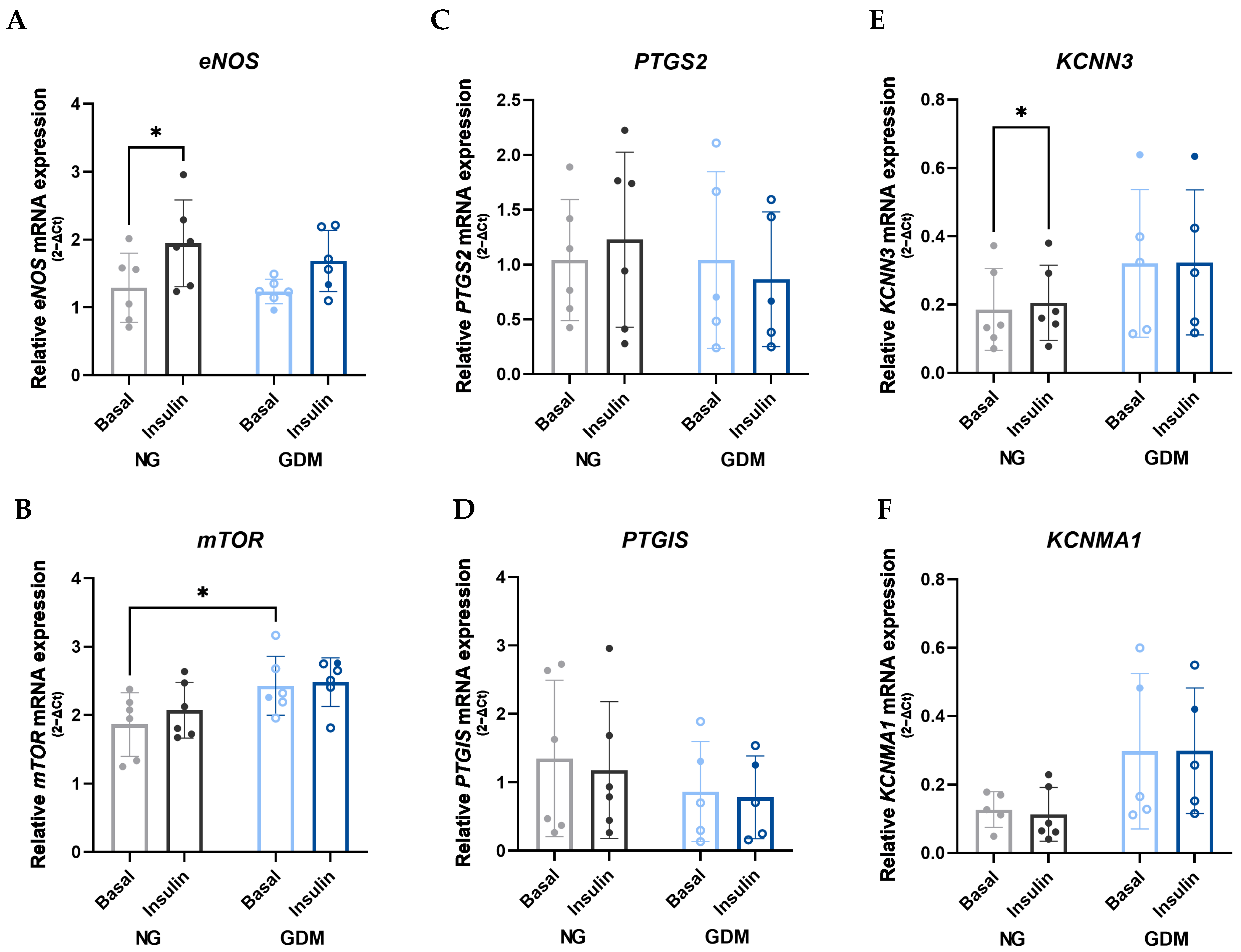

2.3. Disruption of the AKT/eNOS Signaling Pathway Due to Maternal GDM

3. Discussion

4. Limitations

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Clinical Data and Tissue Collection

5.2. Fetoplacental Vessels Isolation

5.3. Mulvany Myograph

5.4. Endothelial Cells Isolation and Culture

5.5. Insulin Stimulation of Endothelial Cells

5.6. RNA Isolation and RT-qPCR

5.7. Protein Isolation and Western Blotting

5.8. Statistical Analysis

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Apgar | Activity, pulse, grimace, appearance, respiration |

| ARDS | Acute respiratory distress syndrome |

| CSH-1, 2 | Chorionic Somatomammotropin Hormone 1, 2 |

| CVD | Cardiovascular diseases |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| EDHF | Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor |

| eNOS | Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| GDM | Gestational Diabetes Mellitus |

| INSR | Insulin Receptor |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| KCNMA1 | Potassium calcium-activated channel subfamily M alpha 1 |

| KCNN3 | Potassium calcium-activated channel subfamily N member 3 |

| mTOR | Mechanistic Target Of Rapamycin kinase |

| NG | Normoglycemic |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| OGTT | Oral Glucose Tolerance Test |

| p-eNOS | Phosphorylated endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| p-INSR | Phosphorylated Insulin Receptor |

| PTGIS | Prostaglandin I2 synthase |

| PTGS2 | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

References

- World Health Organization. Meeting of the Guideline Development Group for the Monitoring and Management of Hyperglycaemia in Pregnancy. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-04-2025-meeting-of-the-guideline-development-group-for-the-monitoring-and-management-of-hyperglycaemia-in-pregnancy (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Wu, X.; Tiemeier, H.; Xu, T. Trends in gestational diabetes prevalence in China from 1990 to 2024: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2025, 26, 1009–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 11th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Saravanan, P.; Diabetes in Pregnancy Working Group; Maternal Medicine Clinical Study Group; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, UK. Gestational diabetes: Opportunities for improving maternal and child health. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeting, A.; Hannah, W.; Backman, H.; Catalano, P.; Feghali, M.; Herman, W.H.; Hivert, M.F.; Immanuel, J.; Meek, C.; Oppermann, M.L.; et al. Epidemiology and management of gestational diabetes. Lancet 2024, 404, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathirana, M.M.; Lassi, Z.S.; Roberts, C.T.; Andraweera, P.H. Cardiovascular risk factors in offspring exposed to gestational diabetes mellitus in utero: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2020, 11, 599–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Tan, B.; Du, R.; Chong, Y.S.; Zhang, C.; Koh, A.S.; Li, L.J. Gestational diabetes mellitus and development of intergenerational overall and subtypes of cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Arah, O.A.; Liew, Z.; Cnattingius, S.; Olsen, J.; Sørensen, H.T.; Qin, G.; Li, J. Maternal diabetes during pregnancy and early onset of cardiovascular disease in offspring: Population based cohort study with 40 years of follow-up. BMJ 2019, 367, l6398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longtine, M.S.; Nelson, D.M. Placental dysfunction and fetal programming: The importance of placental size, shape, histopathology, and molecular composition. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2011, 29, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornburg, K.L. The programming of cardiovascular disease. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2015, 6, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, R.L.; Bitar, L.; Rajagopalan, V.; Spong, C.Y. Interdependence of placenta and fetal cardiac development. Prenat. Diagn. 2024, 44, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tocantins, C.; Diniz, M.S.; Grilo, L.F.; Pereira, S.P. The birth of cardiac disease: Mechanisms linking gestational diabetes mellitus and early onset of cardiovascular disease in offspring. WIREs Mech. Dis. 2022, 14, e1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, S.; Li, M.; Li, L.; Qi, L.; He, Y.; Xu, Z.; Tang, J. Influence of gestational diabetes mellitus on the cardiovascular system and its underlying mechanisms. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1474643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Lan, C.; Fan, C.; Gong, X.; Chen, C.; Yu, C.; Wang, J.; Luo, X.; Hu, C.; Jose, P.A.; et al. Down-regulation of AMPK/PPARδ signalling promotes endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced endothelial dysfunction in adult rat offspring exposed to maternal diabetes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 2304–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Dekou, V.; Hanson, M.; Poston, L.; Taylor, P. Predictive adaptive responses to maternal high-fat diet prevent endothelial dysfunction but not hypertension in adult rat offspring. Circulation 2004, 110, 1097–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Duarte, S.; Carvajal, L.; Garchitorena, M.J.; Subiabre, M.; Fuenzalida, B.; Cantin, C.; Farias, M.; Leiva, A. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Treatment Schemes Modify Maternal Plasma Cholesterol Levels Dependent to Women s Weight: Possible Impact on Feto-Placental Vascular Function. Nutrients 2020, 12, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, I. Molecular mechanisms underlying the activation of eNOS. Pflug. Arch. 2010, 459, 793–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subiabre, M.; Villalobos-Labra, R.; Silva, L.; Fuentes, G.; Toledo, F.; Sobrevia, L. Role of insulin, adenosine, and adipokine receptors in the foetoplacental vascular dysfunction in gestational diabetes mellitus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, H.; Kempf, K.; Röhling, M.; Martin, S. Insulin: Too much of a good thing is bad. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, J.; Manrique-Acevedo, C.; Martinez-Lemus, L.A. New insights into mechanisms of endothelial insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2022, 323, H1231–H1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, E.J.; Hong, S.Y.; Lee, J.H. Adipokines and Insulin Resistance According to Characteristics of Pregnant Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Metab. J. 2017, 41, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabelli, M.; Tocci, V.; Donnici, A.; Giuliano, S.; Sarnelli, P.; Salatino, A.; Greco, M.; Puccio, L.; Chiefari, E.; Foti, D.P.; et al. Maternal Preconception Body Mass Index Overtakes Age as a Risk Factor for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaskolka, D.; Retnakaran, R.; Zinman, B.; Kramer, C.K. Sex of the baby and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus in the mother: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2015, 58, 2469–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retnakaran, R.; Kramer, C.K.; Ye, C.; Kew, S.; Hanley, A.J.; Connelly, P.W.; Sermer, M.; Zinman, B. Fetal sex and maternal risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: The impact of having a boy. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seghieri, G.; Di Cianni, G.; Gualdani, E.; De Bellis, A.; Franconi, F.; Francesconi, P. The impact of fetal sex on risk factors for gestational diabetes and related adverse pregnancy outcomes. Acta Diabetol. 2022, 59, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Ma, X.; Ma, L. Effects of gestational diabetes mellitus on offspring: A literature review. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2025, 171, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskild, A.; Haavaldsen, C.; Vatten, L.J. Placental weight and placental weight to birthweight ratio in relation to Apgar score at birth: A population study of 522 360 singleton pregnancies. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2014, 93, 1302–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oulerich, Z.; Sferruzzi-Perri, A.N. Early-life exposures and long-term health: Adverse gestational environments and the programming of offspring renal and vascular disease. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2024, 327, F21–F36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.; Sferruzzi-Perri, A. The Role of the Placenta in DOHaD. In Developmental Origins of Health and Disease; Poston, L., Godfrey, K.M., Gluckman, P.D., Hanson, M.A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 166–175. [Google Scholar]

- Strøm-Roum, E.M.; Haavaldsen, C.; Tanbo, T.G.; Eskild, A. Placental weight relative to birthweight in pregnancies with maternal diabetes mellitus. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2013, 92, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.; Taricco, E.; Cardellicchio, M.; Mandò, C.; Massari, M.; Savasi, V.; Cetin, I. The role of obesity and gestational diabetes on placental size and fetal oxygenation. Placenta 2021, 103, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lean, S.C.; Heazell, A.E.P.; Dilworth, M.R.; Mills, T.A.; Jones, R.L. Placental Dysfunction Underlies Increased Risk of Fetal Growth Restriction and Stillbirth in Advanced Maternal Age Women. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeckel, K.M.; Boyarko, A.C.; Bouma, G.J.; Winger, Q.A.; Anthony, R.V. Chorionic somatomammotropin impacts early fetal growth and placental gene expression. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 237, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Männik, J.; Vaas, P.; Rull, K.; Teesalu, P.; Rebane, T.; Laan, M. Differential expression profile of growth hormone/chorionic somatomammotropin genes in placenta of small- and large-for-gestational-age newborns. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 2433–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassie, K.; Giri, R.; Joham, A.E.; Teede, H.; Mousa, A. Human Placental Lactogen in Relation to Maternal Metabolic Health and Fetal Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannik, J.; Vaas, P.; Rull, K.; Teesalu, P.; Laan, M. Differential placental expression profile of human Growth Hormone/Chorionic Somatomammotropin genes in pregnancies with pre-eclampsia and gestational diabetes mellitus. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2012, 355, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, J. Diabetes and pregnancy; blood sugar of newborn infants during fasting and glucose administration. Ugeskr. Laeger. 1952, 114, 685. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, H.O.; Chaker, H.; Leaming, R.; Johnson, A.; Brechtel, G.; Baron, A.D. Obesity/insulin resistance is associated with endothelial dysfunction. Implications for the syndrome of insulin resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 1996, 97, 2601–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadoran, Z.; Mirmiran, P.; Kashfi, K.; Ghasemi, A. Vascular nitric oxide resistance in type 2 diabetes. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, M.T.; Creager, S.J.; Scales, K.M.; Cusco, J.A.; Lee, B.K.; Creager, M.A. Impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Circulation 1993, 88, 2510–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, K.S.; Hernandez, P.V.; Maurer, G.S.; Wetzel, E.M.; Sun, M.; Jalal, D.I.; Stanhewicz, A.E. Impaired microvascular insulin-dependent dilation in women with a history of gestational diabetes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2024, 327, H793–H803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstens, P.S.; Brendel, H.; Villar-Ballesteros, M.L.; Mittag, J.; Hengst, C.; Brunssen, C.; Birdir, C.; Taylor, P.D.; Poston, L.; Morawietz, H. Characterization of human placental fetal vessels in gestational diabetes mellitus. Pflug. Arch. 2025, 477, 67–79, Correction in Pflug. Arch. 2025, 477, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, M.; Sakaguchi, M.; Lockhart, S.M.; Cai, W.; Li, M.E.; Homan, E.P.; Rask-Madsen, C.; Kahn, C.R. Endothelial insulin receptors differentially control insulin signaling kinetics in peripheral tissues and brain of mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E8478–E8487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Mima, A.; Li, Q.; Rask-Madsen, C.; He, P.; Mizutani, K.; Katagiri, S.; Maeda, Y.; Wu, I.-H.; Mogher Khamaisi, M.; et al. Insulin decreases atherosclerosis by inducing endothelin receptor B expression. JCI Insight 2016, 1, e86574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, K.M.; Barrett, E.J.; Malin, S.K.; Reusch, J.E.B.; Regensteiner, J.G.; Liu, Z. Diabetes pathogenesis and management: The endothelium comes of age. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 13, 500–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.A.; Montagnani, M.; Koh, K.K.; Quon, M.J. Reciprocal relationships between insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction: Molecular and pathophysiological mechanisms. Circulation 2006, 113, 1888–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanello, P.; Schneider, D.; Herrera, E.A.; Uauy, R.; Krause, B.J. Endothelial heterogeneity in the umbilico-placental unit: DNA methylation as an innuendo of epigenetic diversity. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, B.J.; Prieto, C.P.; Muñoz-Urrutia, E.; San Martín, S.; Sobrevia, L.; Casanello, P. Role of arginase-2 and eNOS in the differential vascular reactivity and hypoxia-induced endothelial response in umbilical arteries and veins. Placenta 2012, 33, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.J.; Wang, X.; Li, Q.; Huang, H.; Zheng, Q.L.; Yao, Q.; Zhang, J. Feto-placental endothelial dysfunction in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus under dietary or insulin therapy. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2023, 23, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sissaoui, S.; Egginton, S.; Ting, L.; Ahmed, A.; Hewett, P.W. Hyperglycaemia up-regulates placental growth factor (PlGF) expression and secretion in endothelial cells via suppression of PI3 kinase-Akt signalling and activation of FOXO1. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.L.; Edelstein, D.; Dimmeler, S.; Ju, Q.; Sui, C.; Brownlee, M. Hyperglycemia inhibits endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity by posttranslational modification at the Akt site. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 108, 1341–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Wu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, C.; Hu, C.; Liu, Z.; Luo, X.; Wang, J.; et al. Exposure to maternal diabetes induces endothelial dysfunction and hypertension in adult male rat offspring. Microvasc. Res. 2021, 133, 104076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollberg, S.; Brockman, D.E.; Myatt, L. Nitric oxide synthase activity in umbilical and placental vascular tissue of gestational diabetic pregnancies. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 1997, 44, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarahmadi, A.; Azarpira, N.; Mostafavi-Pour, Z. Role of mTOR Complex 1 Signaling Pathway in the Pathogenesis of Diabetes Complications; A Mini Review. Int. J. Mol. Cell. Med. 2021, 10, 181–189. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, S.H.; Emdal, K.B.; Pedersen, A.-K.; Axelsen, L.N.; Kildegaard, H.F.; Demozay, D.; Pedersen, T.A.; Grønborg, M.; Slaaby, R.; Nielsen, P.K.; et al. Multi-layered proteomics identifies insulin-induced upregulation of the EphA2 receptor via the ERK pathway which is dependent on low IGF1R level. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong Van Huyen, J.P.; Vessières, E.; Perret, C.; Troise, A.; Prince, S.; Guihot, A.-L.; Barbry, P.; Henrion, D.; Bruneval, P.; Laurent, S.; et al. In utero exposure to maternal diabetes impairs vascular expression of prostacyclin receptor in rat offspring. Diabetes 2010, 59, 2597–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, K.; Kitazono, T. Endothelium-Dependent Hyperpolarization (EDH) in Diabetes: Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NG (n = 33) | GDM (n = 19) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal data | |||

| Age (years) (mean ± SD) Body Mass Index (kg/m2) (mean ± SD) Weeks of pregnancy (mean ± SD) Fasting glycemia (mM) (mean ± SD) Glycemia 1 h post glucose ingestion (mM) (mean ± SD) Glycemia 2 h post glucose ingestion (mM) (mean ± SD) Delivery mode (vaginal/cesarean) | 33.68 ± 4.66 23.88 ± 5.20 39.23 ± 1.10 4.81 ± 0.70 6.71 ± 0.73 6.06 ± 1.04 9:24 | 36.00 ± 6.16 30.72 ± 8.44 38.46 ± 0.63 5.25 ± 0.54 9.94 ± 1.31 8.09 ± 1.24 0:19 | 0.1474 (ns) 0.0012 (**) 0.0122 (*) 0.0788 (ns) <0.0001 (****) 0.0058 (**) 0.0184 (*) |

| Neonatal data | |||

| Sex (male/female) Birth weight (g) (mean ± SD) Apgar score 1 min (median (IQR)) Apgar score 5 min (median (IQR)) Apgar score 10 min (median (IQR)) | 21:12 3348.18 ± 403.57 9 (0) 10 (1) 10 (0) | 11:8 3360.56 ± 624.48 9 (1) 9 (1.75) 10 (0) | 0.7708 (ns) 0.9334 (ns) 0.4119 (ns) 0.0057 (**) 0.9752 (ns) |

| Placental data | |||

| Placental weight (g) (mean ± SD) Placental width (cm) (mean ± SD) Placental length (cm) (mean ± SD) Placental area (cm2) (mean ± SD) Umbilical cord weight (g) (mean ± SD) Umbilical cord length (cm) (mean ± SD) | 526.71 ± 103.84 16.74 ± 1.93 19.26 ± 2.81 253.59 ± 50.72 30.88 ± 11.53 39.52 ± 12.15 | 707.31 ± 128.09 18.53 ± 2.22 21.94 ± 3.80 323.47 ± 87.57 35.75 ± 15.05 39.80 ± 11.54 | 0.0008 (***) 0.0120 (*) 0.0230 (*) 0.0094 (**) 0.3553 (ns) 0.9401 (ns) |

| Target Gene | Primer Name | Amplicon Size | Sequence (5′ ⟶ 3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chorionic somatomammotropin hormone 1 (CSH-1 or hPL-A) | CSH-1 forward | 139 | ACTGCTCAAGAACTACGGGC |

| CSH-1 reverse | 139 | AGGGGTCACAGGATGCTACT | |

| Chorionic somatomammotropin hormone 2 (CSH-2 or hPL-B) | CSH-2 forward | 81 | CATCCTGTGACCGACCCCT |

| CSH-2 reverse | 81 | TATTAGGACAAGGCTGATGGGC | |

| Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase | eNOS forward | 146 | GAACCTGTGTGACCCTCACCCC |

| eNOS reverse | 146 | TGGCTAGCTGGTAACTGTGC | |

| Mammalian target of rapamycin | mTOR forward | 137 | GGCCATCCGGGAATTTTTGT |

| mTOR reverse | 137 | TCGTGCTCTGAATTGAGGTGT | |

| Potassium Calcium-Activated Channel Subfamily M Alpha 1 | KCNMA1 forward | 527 | GGTGTTGGGTGAGTTCC |

| KCNMA1 reverse | 527 | TCTCCAGTGCCTTCGTG | |

| Potassium Calcium-Activated Channel Subfamily N Member 3 (SKCa3) | KCNN3 forward | 174 | GTTCCATCTTGACGCTCCTC |

| KCNN3 reverse | 174 | TGGACACTCAGCTCACCAAG | |

| Prostaglandin I2 Synthase | PTGIS forward | 103 | GGGATCTCCACATCTGCGTT |

| PTGIS reverse | 103 | ACTGCCTGGGGAGGAGTTAT | |

| Prostaglandin-Endoperoxide Synthase 2 | PTGS2 forward | 223 | GTTGGTGGCGGTGACTTGTT |

| PTGS2 reverse | 223 | AGATCATAAGCGAGGGCCAG | |

| TATA-Binding Protein | TBP forward | 133 | CGCCGGCTGTTTAACCTTCG |

| TBP reverse | 133 | AGAGCATCTCCAGCACACTC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hengst, C.M.; Villar-Ballesteros, M.d.L.; Brendel, H.; Giebe, S.; Brunssen, C.; Frühauf, A.; Birdir, C.; Taylor, P.D.; Poston, L.; Morawietz, H. Maternal Gestational Diabetes Impairs Fetoplacental Insulin-Induced Vasodilation via AKT/eNOS Pathway and Reduces Placental Efficiency. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11507. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311507

Hengst CM, Villar-Ballesteros MdL, Brendel H, Giebe S, Brunssen C, Frühauf A, Birdir C, Taylor PD, Poston L, Morawietz H. Maternal Gestational Diabetes Impairs Fetoplacental Insulin-Induced Vasodilation via AKT/eNOS Pathway and Reduces Placental Efficiency. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11507. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311507

Chicago/Turabian StyleHengst, Clara M., Maria de Leyre Villar-Ballesteros, Heike Brendel, Sindy Giebe, Coy Brunssen, Alexander Frühauf, Cahit Birdir, Paul D. Taylor, Lucilla Poston, and Henning Morawietz. 2025. "Maternal Gestational Diabetes Impairs Fetoplacental Insulin-Induced Vasodilation via AKT/eNOS Pathway and Reduces Placental Efficiency" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11507. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311507

APA StyleHengst, C. M., Villar-Ballesteros, M. d. L., Brendel, H., Giebe, S., Brunssen, C., Frühauf, A., Birdir, C., Taylor, P. D., Poston, L., & Morawietz, H. (2025). Maternal Gestational Diabetes Impairs Fetoplacental Insulin-Induced Vasodilation via AKT/eNOS Pathway and Reduces Placental Efficiency. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11507. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311507