This review systematically examines the role of LPL in metabolic dysfunction and cardiac outcomes in individuals with type 2 diabetes. The findings highlight LPL’s crucial role in lipid metabolism and its potential as a therapeutic target to improve cardiovascular and metabolic outcomes in diabetic populations. This underscores the need for a comprehensive understanding of LPL’s mechanistic pathways and its interactions with other metabolic processes, including gene regulation, to address the complexities of T2D-related cardiovascular complications.

4.1. LPL and Metabolic Dysregulation in Type 2 Diabetes

LPL is a key enzyme responsible for the hydrolysis of triglycerides in lipoproteins, such as chylomicrons and very low-density lipoproteins [

24]. This process allows for the release of free fatty acids and glycerol in tissues such as the heart, muscle, and fat. In T2D patients, on the other hand, there is a profound decline in LPL activity. This contributes to dyslipidemia, one of the critical features of T2D. In particular, the impaired hydrolysis of TGs results in increased circulating levels of VLDL and TGs that, in turn, promote an increase in atherogenic lipoproteins, including IDL and small, dense LDL particles [

25].

Indeed, this review was corroborated by all the studies that have shown LPL activity to be reduced in T2D patients and associated with disturbances in lipid metabolism [

9,

12]. This dysregulation in lipid metabolism is considered a critical contributor to the development of CVD, given both the well-documented high risks for atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction presented by elevated TGs and low HDL cholesterol levels. According to Xia et al., the mechanisms of reduced LPL activity may be related to several biological processes, such as gene polymorphisms, inflammatory cytokines, and insulin resistance [

9].

Polymorphisms in the LPL gene result in differences in capacity and lipid processes at the molecular level. Polymorphisms in the LPL gene are reported to alter enzyme activity and lead to lipid profile derangement in T2DM, among other things, through S447X polymorphism [

26]. These genetic variants produced a functional alteration in the gene expression of LPL, some of which resulted in either up-regulation or down-regulation of the activity of LPL that, in turn, affected the lipid profile and insulin sensitivity. Hypothetically, diminished LPL activity regarding T2D could augment circulating triglyceride concentrations and increase lipotoxicity, characterized by the adverse impact of excess fatty acids on insulin signaling and glucose homeostasis and worsening insulin resistance [

27].

However, T2D increases LPL suppression by setting up an inflammatory environment. TNF-α and IL-6 normally function as anti-inflammatory cytokines, preventing LPL transcription and, thus, lowering its enzymatic activity [

28]. These cytokines exert characteristic T2D imprints, leading to endothelial dysfunction, insulin resistance, and altered lipid profile metabolism. According to this study, LPL could play a key role in messing up the lipid metabolism of patients with cardiovascular disease. Reduced LPL activity culminates in the accumulation of lipids in cardiac tissues, thereby crippling mitochondrial function and encouraging oxidative stress, hence accelerating the development of heart disease. Several studies in this review show that higher LPL activity is associated with a more favorable lipid profile and lower myocardial stress markers, indicating its protective role for cardiac health [

29].

Besides the metabolic function, LPL directly influences cardiac substrate utilization. Interestingly, overexpression of VEGF-B growth factor is known to regulate LPL activity-enhanced LPL activity in cardiac tissue and improve insulin sensitivity, suggesting that LPL may act as a mediator of the beneficial effects of VEGF-B on the heart [

28]. The ability of VEGF-B to increase the expression and activity of LPL in cardiomyocytes increases the efficiency of fatty acid oxidation, thus providing an energy source that sustains myocardial function. This mainly occurs under diabetic conditions where impaired glucose utilization has occurred. According to Shang [

10], this relationship is thrilling since it offers a wide avenue for gene therapy or pharmacological intervention against VEGF-B signaling as a possible treatment for diabetic cardiomyopathy.

Clinically, this would reduce myocardial lipid accumulation and lighten the load on the heart, which is beneficial in managing diabetic cardiomyopathy. Additionally, heightened LPL might improve endothelial function, reduce vascular inflammation, and reduce oxidative stress, which is central to the development of atherosclerosis in T2D patients [

30].

While our meta-analysis of human studies establishes a compelling association between LPL modulation and improved lipid profiles, the underlying mechanisms within the cardiac tissue remain inferential in human data. Here, the experimental work by Shang [

10] in a diabetic rat model provides a crucial mechanistic link. Their research demonstrated that cardiac-specific overexpression of VEGF-B enhanced LPL activity in the myocardium, which in turn improved fatty acid oxidation and reduced lipid accumulation. Although derived from an animal model, this finding suggests a plausible pathway through which LPL modulation confers cardioprotection: by enhancing the efficiency of myocardial substrate utilization and mitigating lipotoxicity. This positions the VEGF-B/LPL axis as a promising, albeit experimentally validated, therapeutic target for diabetic cardiomyopathy.

4.2. Integrating Cardiac Metabolomic Findings with LPL Dysregulation

A critical synthesis of cardiac metabolomic alterations and LPL dysfunction reveals a coherent pathological narrative in the diabetic heart. We propose that insulin resistance-induced LPL dysregulation is a key driver of the observed metabolomic perturbations through three primary pathways.

4.2.1. Incomplete Fatty Acid Oxidation

The accumulation of long-chain acylcarnitines [

9,

12] indicates impaired mitochondrial β-oxidation. This aligns with the LPL dysfunction model: an oversupply of fatty acids, coupled with reduced oxidative capacity, leads to metabolic intermediates accumulation, promoting lipotoxicity and cardiac dysfunction.

4.2.2. Sphingolipid-Mediated Pathogenesis

Elevated ceramide levels provide a crucial link between LPL dysfunction and cellular damage. LPL-derived fatty acids (e.g., palmitate) serve as substrates for ceramide synthesis, directly connecting impaired lipid metabolism to insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and cardiomyocyte apoptosis.

4.2.3. Metabolic Inflexibility

Perturbations in branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) and TCA cycle intermediates reflect the heart’s failed adaptation to lipid overload. Excessive fatty acids from inefficient LPL processing inhibit glucose oxidation and BCAA catabolism, compromising energy production and contractile function.

4.2.4. Bridging the Evidence Gap

Human studies show correlation but not causation between LPL dysfunction and metabolomic changes. The animal study by Shang et al. [

10] provides crucial causal evidence: cardiac-specific modulation of VEGF-B/LPL axis normalized the metabolomic profile, positioning LPL activity as an upstream regulator of the cardiac metabolome.

In summary, the diabetic cardiac metabolome reflects the heart’s failed adaptation to LPL dysregulation. This integration provides a mechanistic understanding of diabetic cardiomyopathy beyond mere metabolite listing.

4.3. Gender-Specific Differences in LPL Activity and Lipid Metabolism

One interesting finding in the studies reviewed relates to the gender differences in LPL activities and the lipid metabolism pattern. Yoshida et al., 2025 reported that T2D women exhibited lower LPL activity, higher levels of triglycerides, and lower HDL-C compared to men, with reduced insulin sensitivity [

18]. The observed gender disparity in enzyme activity partly relates to the influence of sex hormones on LPL expression. Estrogens are known to upregulate the activity of LPL, especially in adipose tissue, whereas androgens may either have a minimal effect or suppress the expression of LPL in some tissues [

28]. Such hormonal differences might contribute to the observed Difference in lipid metabolism between men and women with T2D.

More studies will be required to elucidate the effects of these gender-specific differences in LPL activity on other metabolic and hormonal systems and cardiovascular risk in diabetic patients. Therapeutic interventions are also directed at modulating LPL concentrations a priori for their gender-specific effectiveness in enhancing metabolic and cardiovascular profiles.

4.4. Therapies and the Future of Research

These outcomes following this review suggest that modulating LPL activity could be a potential avenue for treating T2D alongside its cardiovascular consequences. However, the examined works indicate that increased LPL activity would benefit lipid profile and insulin sensitivity and decrease myocardial stress. Therefore, therapies that increase LPL synthesis, such as gene therapy, phosphor-LPL, L, or other substances, may be used for T2D patients with an elevated risk of cardiovascular events. This is because a procedure that impacts the VEGF-B signaling pathway is one of the most effective options. According to Shang et al., balancing overexpression of VEGF-B in animal models raises LPL activity in the heart and enhances myocardial function and lipid metabolism. It may further be used in clinical trials to treat DM-induced cardiomyopathy. Exercise and diet to increase the activity of LPL could be used as adjuvant therapies in T2D since they are effective in managing T2D.

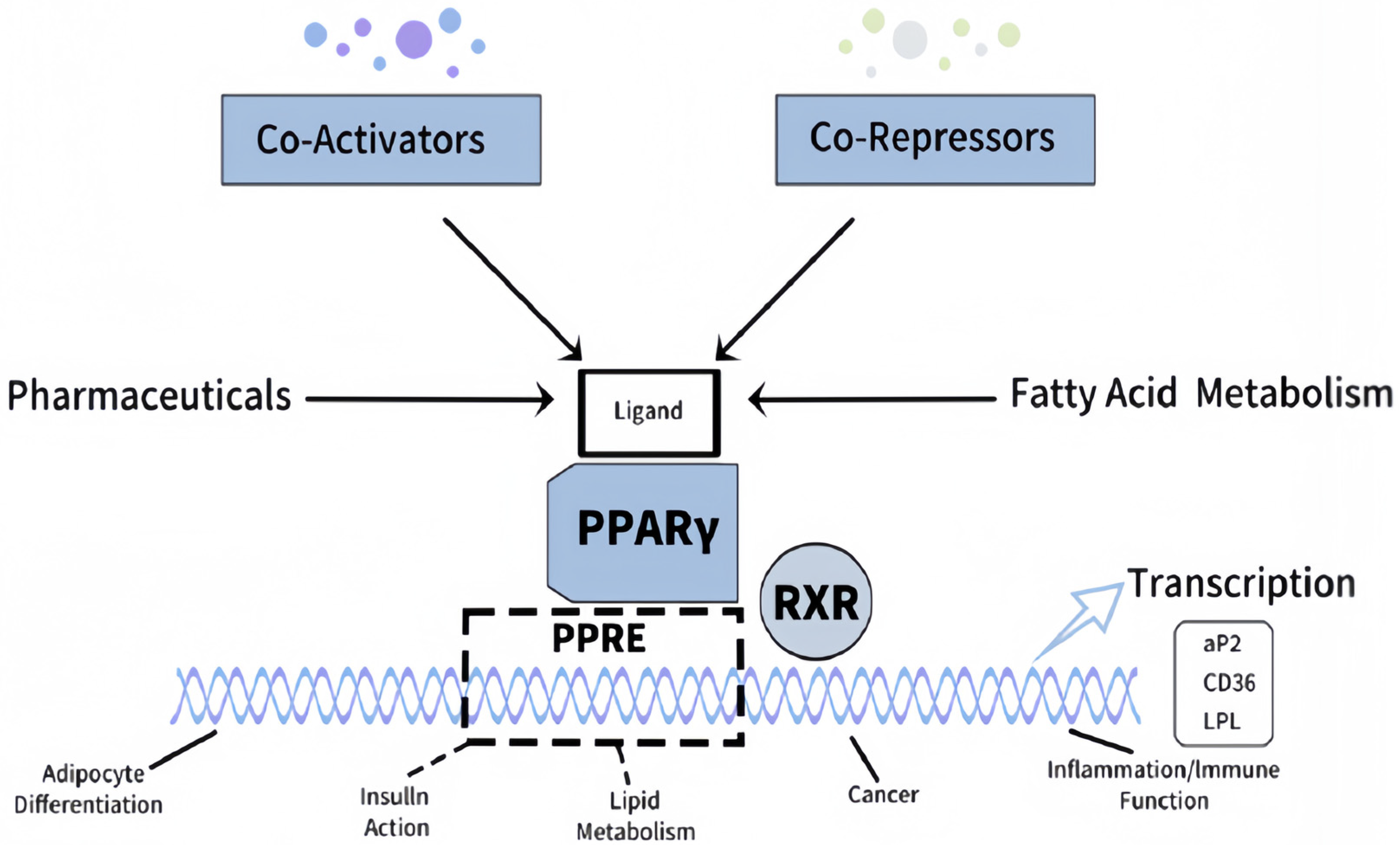

Moreover, PPV could also embrace all genetic approaches, including LPL gene polymorphism, to ascertain optimized treatment methods. For instance, in this case, the therapy augmenting the activity of LPL may be more beneficial among patients with diverse mutations of the LPL gene. Thus, at the same time, a different approach to treatment is required when LPL activity is low in patients [

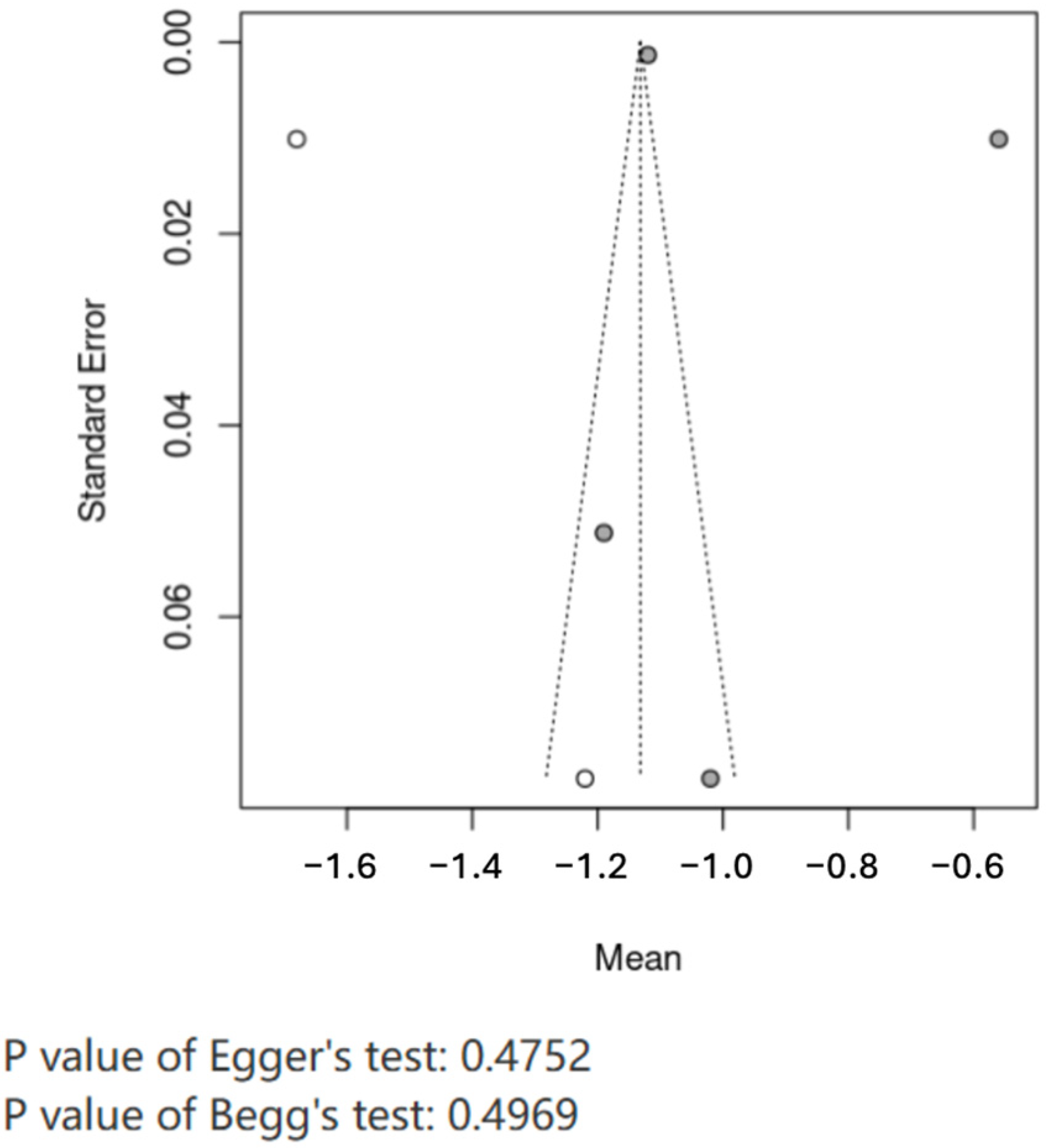

31]. Investigating epigenetic modifications’ role in controlling LPL expression in the future would be interesting. Epigenetic characteristics, such as DNA methylation and histone modification, influence LPL gene expression in the heart and adipose tissue. It would be more attractive to see how environmental factors such as diet and exercise influence epigenetic LPL regulation to provide new insights into developing personalized treatments for T2D and cardiovascular disease. We have provided substantial evidence that augmentation of LPL activity improves the lipid profile and minimizes myocardial stress, enhancing insulin sensitivity in diabetic subjects. Gender-specific differences in LPL activity indicate that therapeutic strategies aimed at targeting LPL should consider sex-specific metabolic profiles. Further, modulation of VEGF-B presents a novel route of therapeutic rescue of the LPL activity to improve cardiac outcomes in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Future studies are required to optimize these therapeutic approaches and to investigate further genetic and epigenetic determinants of LPL expression for more effective and personalized treatments against T2D and its cardiovascular complications. Review-level limitations include potential missed grey literature and absence of prospective protocol registration at inception [

15].

4.5. Limitations

The inclusion of an animal study, while instrumental in providing mechanistic insights not available from the human literature, means that our evidence synthesis is not exclusively based on human data. The translational applicability of these mechanistic findings to human pathophysiology and their ultimate clinical relevance require further validation in human cohorts and clinical trials.

Furthermore, while we prioritized the inclusion of studies reporting cardiac outcomes, our eligibility criteria were designed to be inclusive of seminal mechanistic work. Consequently, one included study does not report direct cardiac risk data but was retained for its foundational contribution to understanding the PPARγ-LPL pathway. Additionally, limitations in the available data prevented a systematic adjustment for confounders like age, medication use, ethnicity, and disease duration, which could potentially affect the association between LPL activity and cardio-metabolic outcomes.