Chemical Modification of Thermomyces lanuginosus Lipase and Myceliophthora thermophila Laccase Using Dihydrazides: Biochemical Characterization and In Silico Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

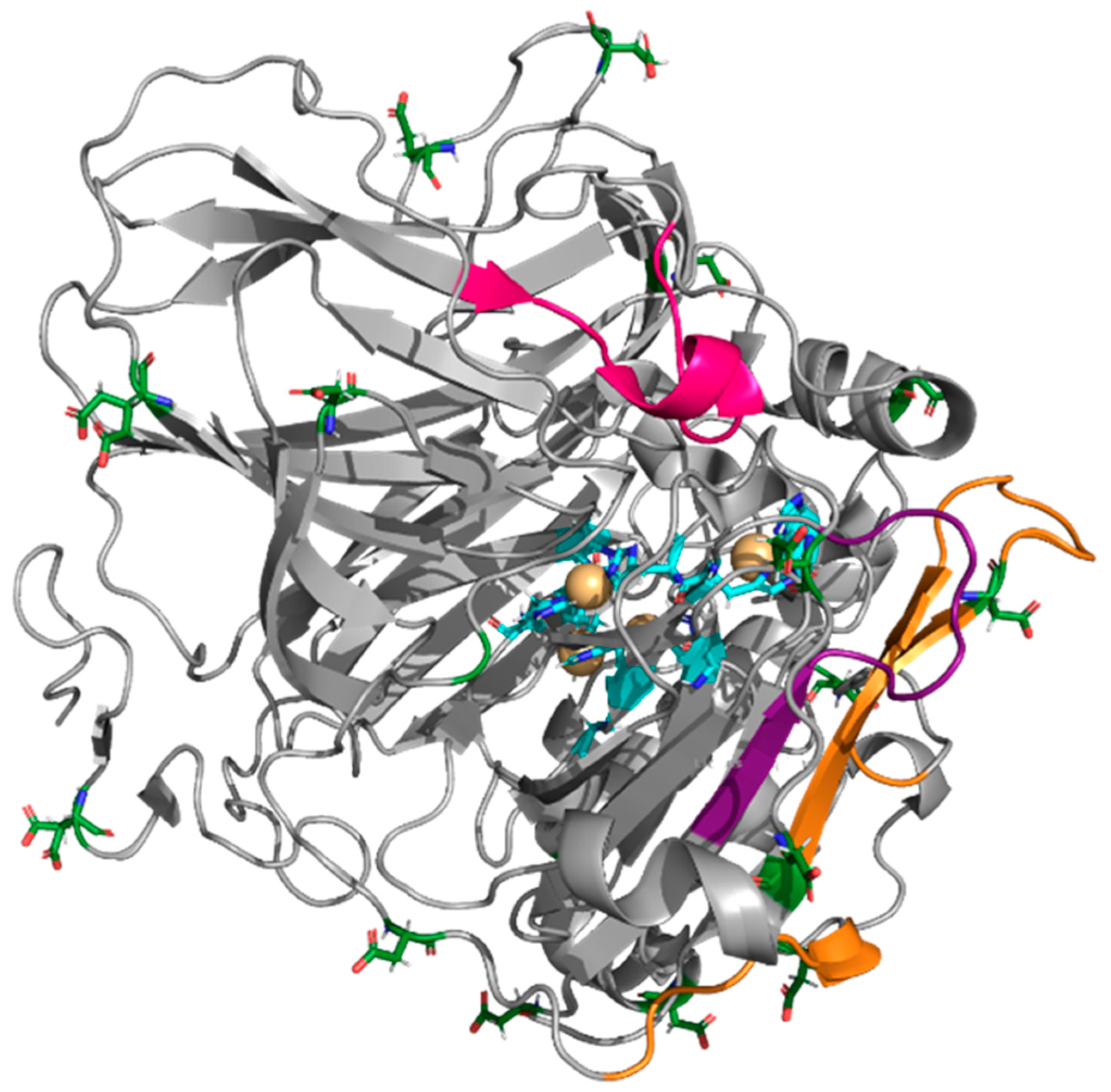

2. Results and Discussion

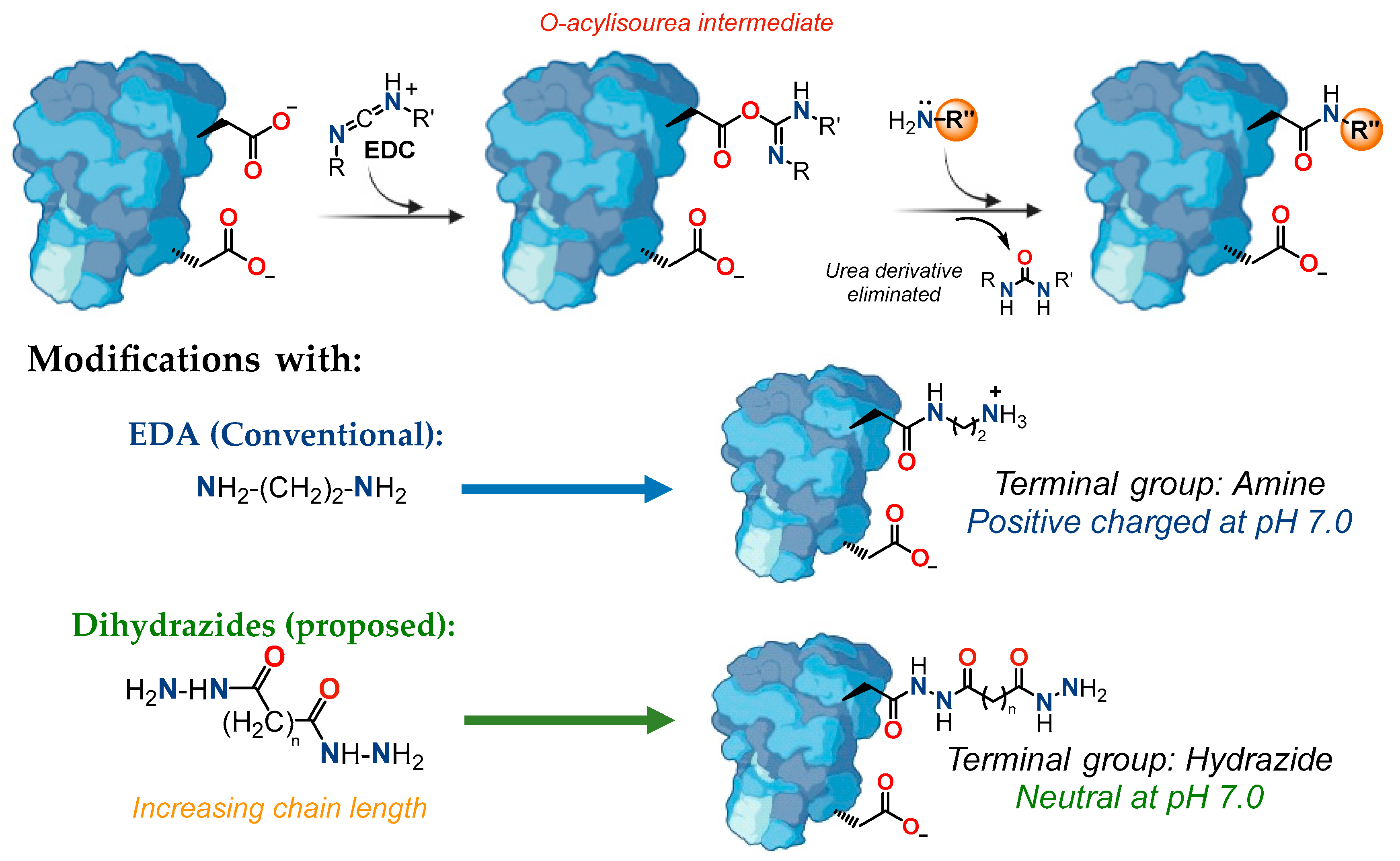

2.1. Enzyme Chemical Modification

2.2. Biocatalytic Characterization of Modified Enzymes

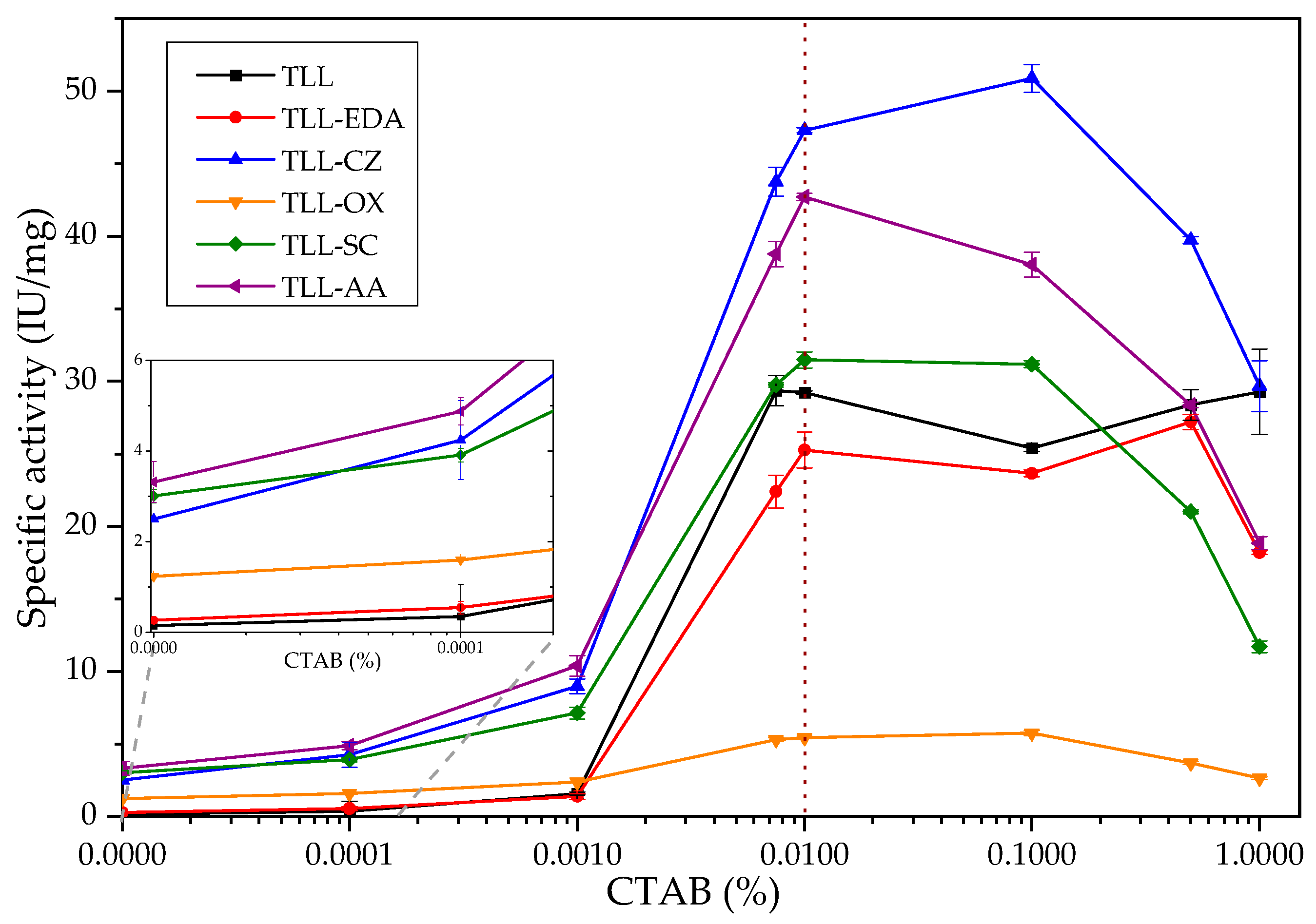

2.2.1. TLL Surfactant Activation Studies: Impact of Chemical Modifications

2.2.2. Kinetic Studies for TLL and Its Variants

2.2.3. Kinetic Studies of MTL and Its Variants

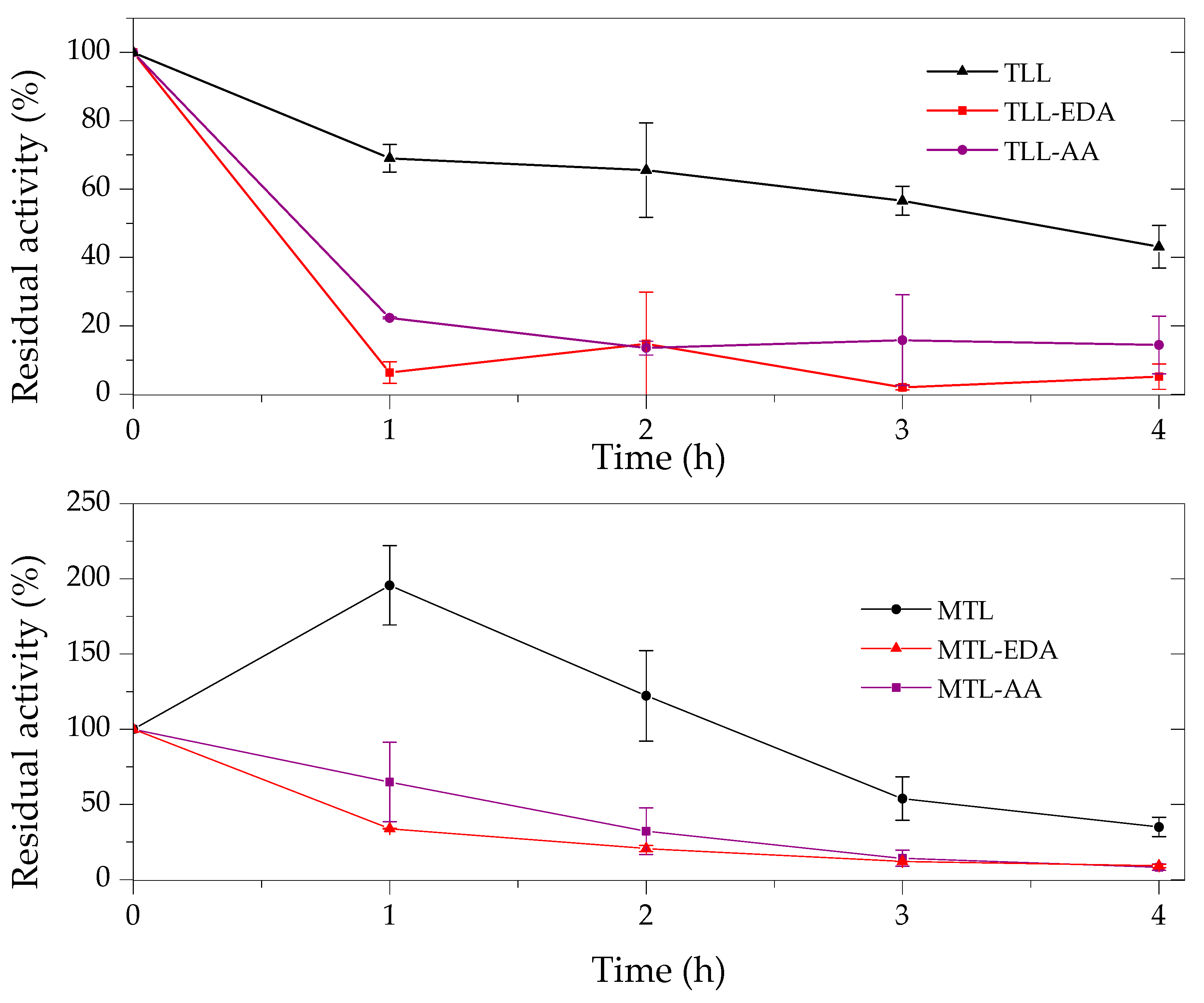

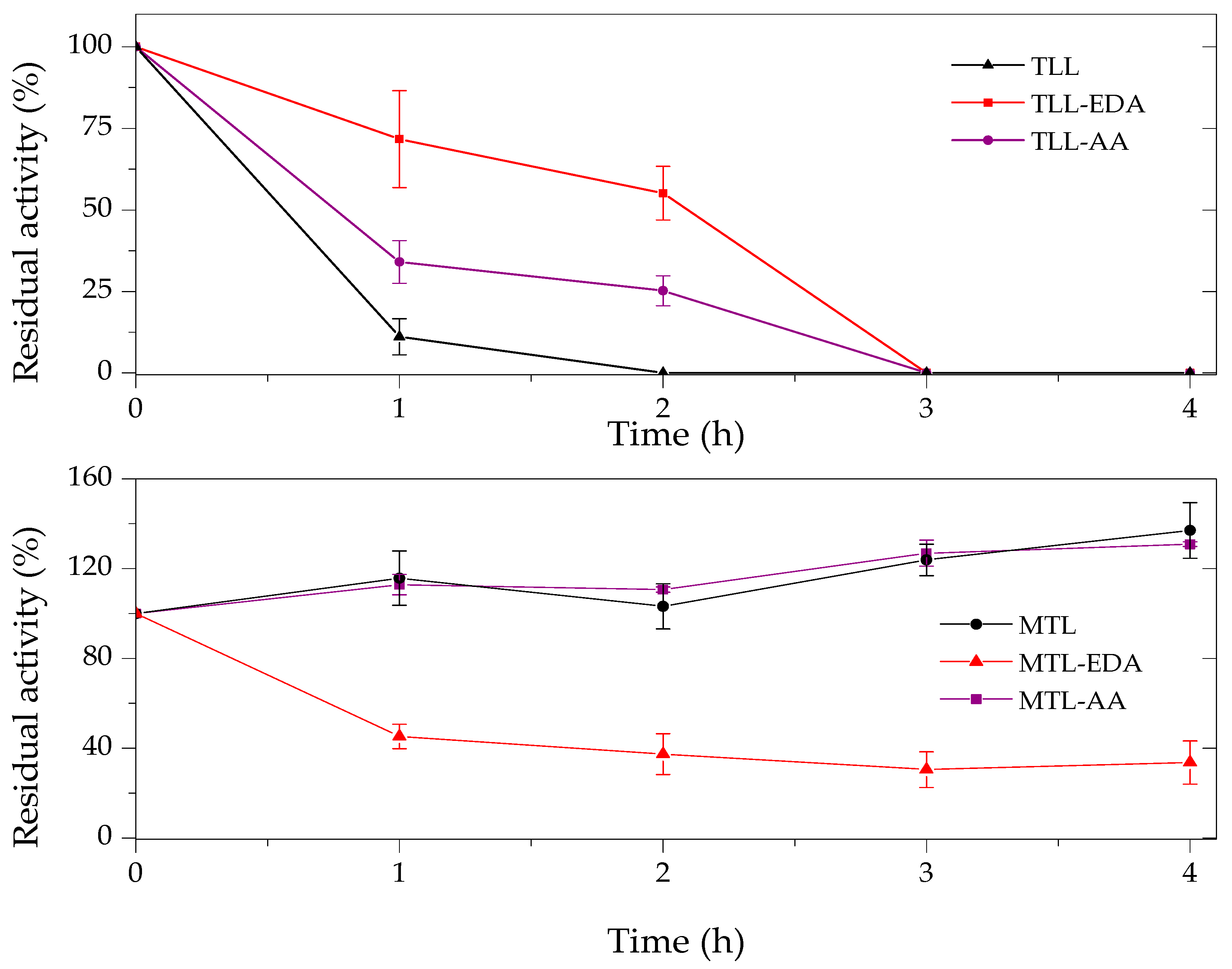

2.3. Thermal and Organic Solvent Stability of Modified Enzymes

2.4. Preliminary Assessment of Biotechnological Applications Using Enzyme Variants

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

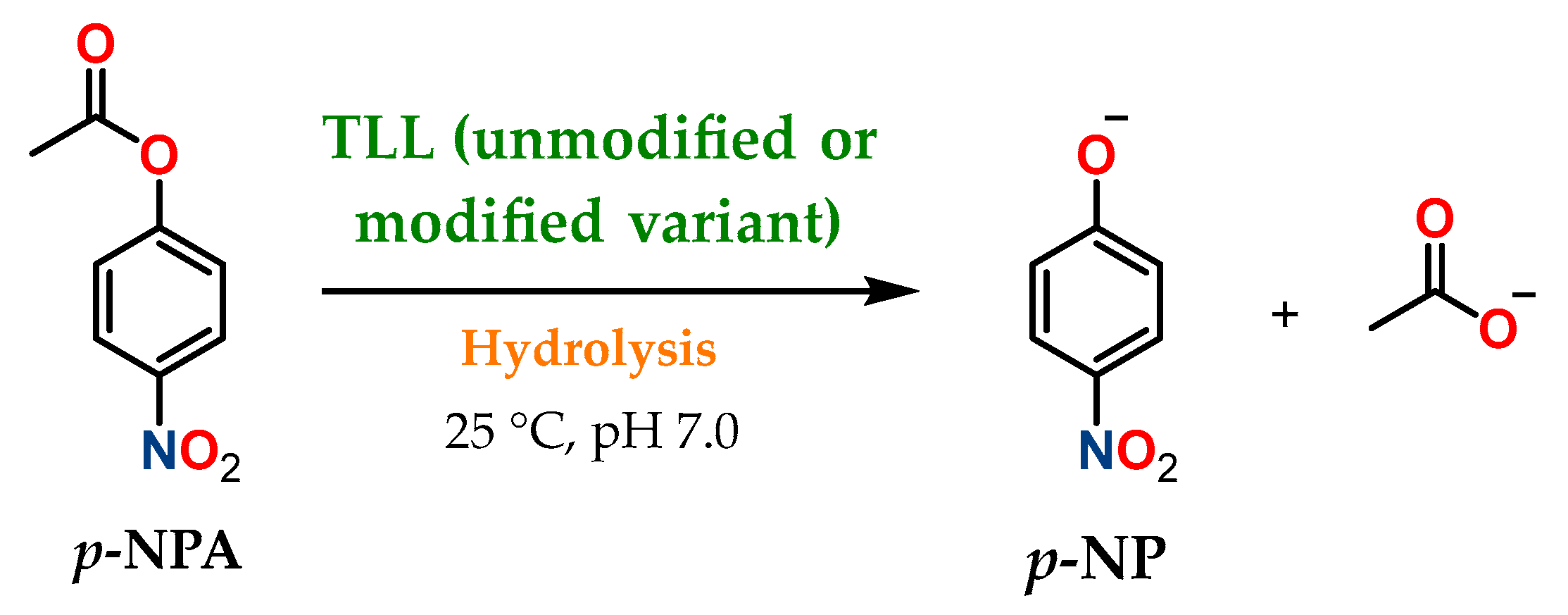

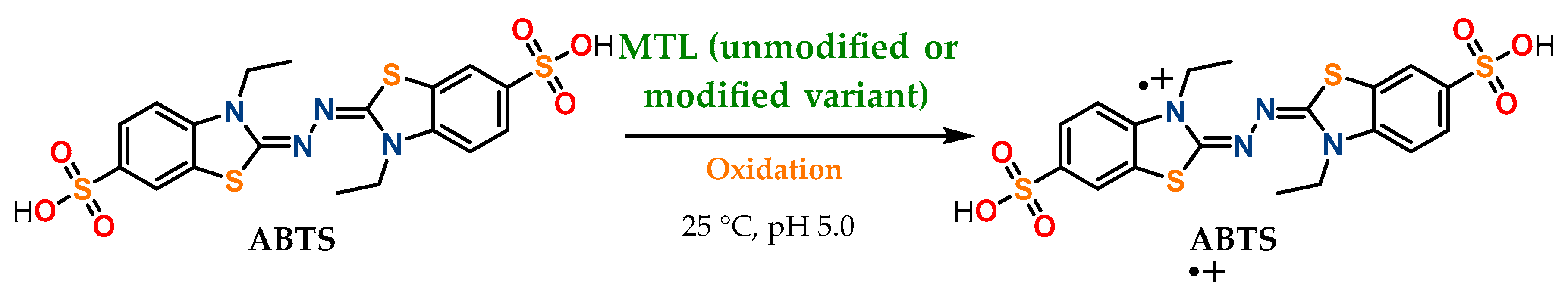

3.2. Esterase and Oxidative Activity Determination

3.3. Protein Determination

3.4. Solid-Phase Enzyme Modification

3.5. Liquid-Phase Enzyme Modification

3.6. Purification of Modified Enzymes

3.7. Determination of Enzyme Surface Modification

3.8. SDS-PAGE Analysis

3.9. Michaelis–Menten Kinetics

3.10. Solvent and Thermal Stability Assays

3.11. Preliminary Assessment of the Obtained Enzymes in Biotechnological Applications

3.11.1. One-Step Solvent-Free Fatty Acid Ethyl Ester Synthesis (FAEs)

3.11.2. Indigo Carmine Decolorization

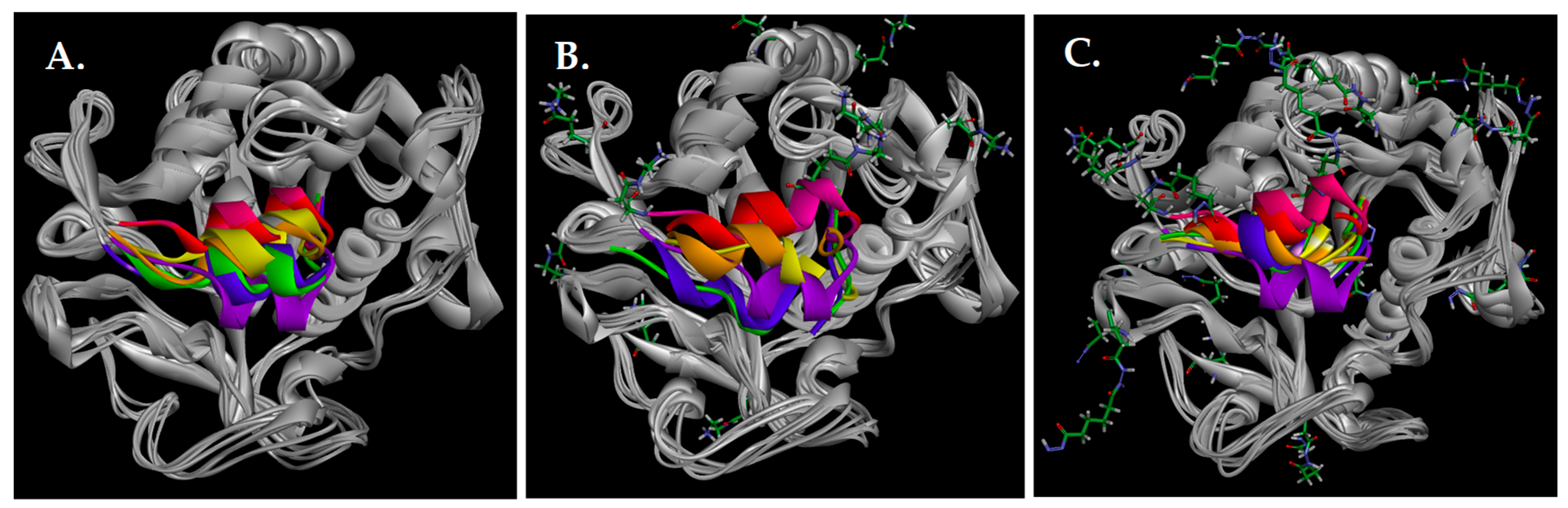

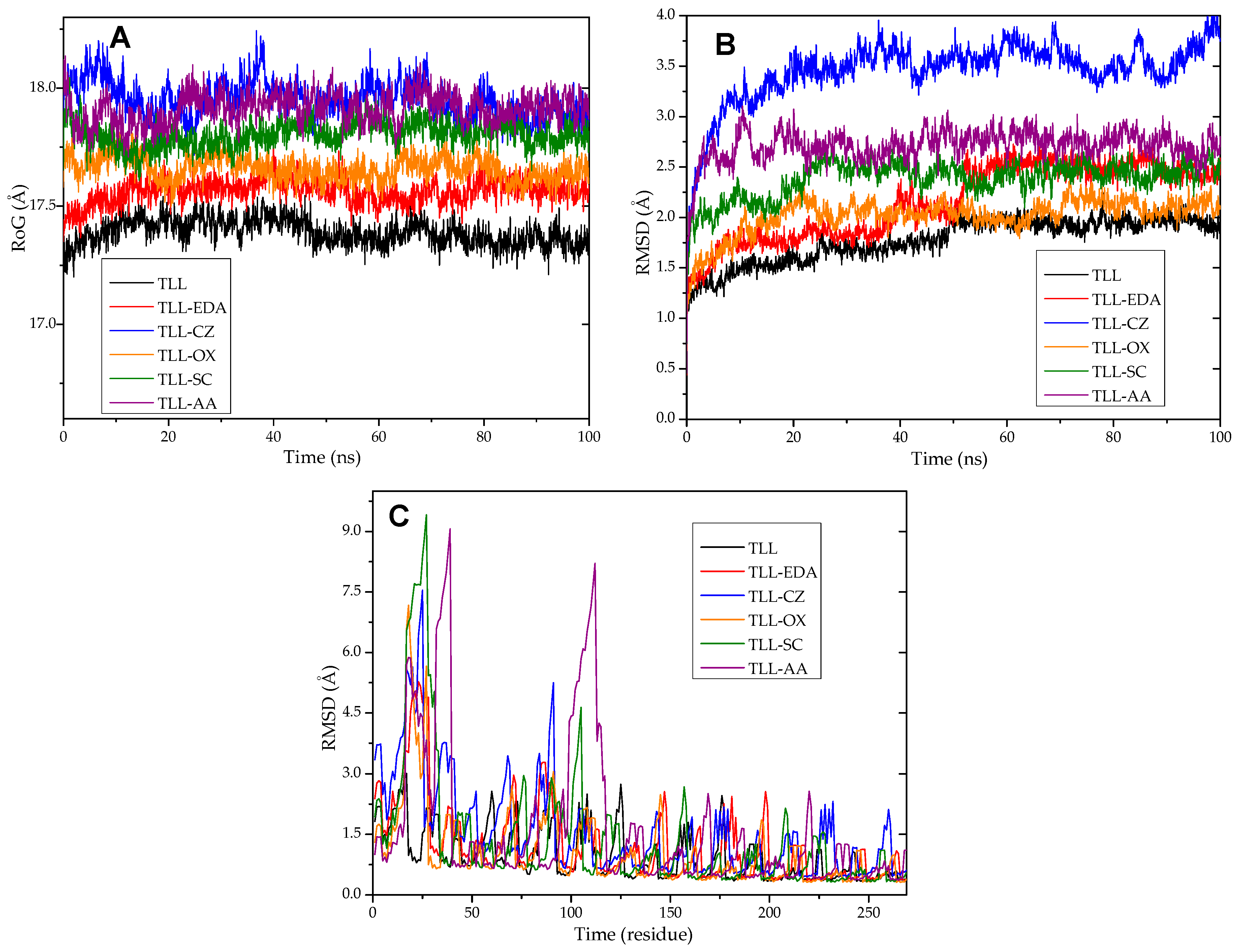

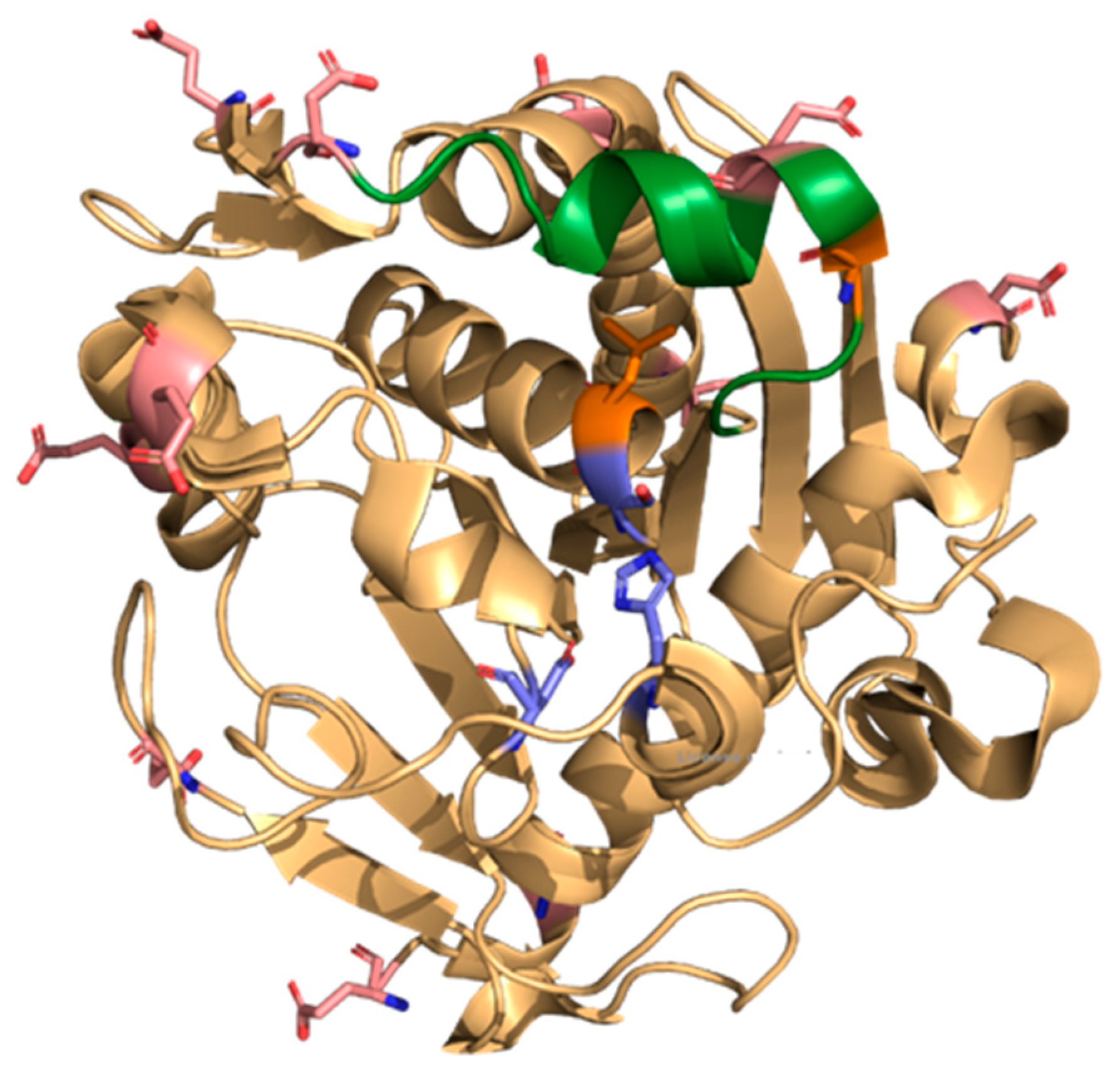

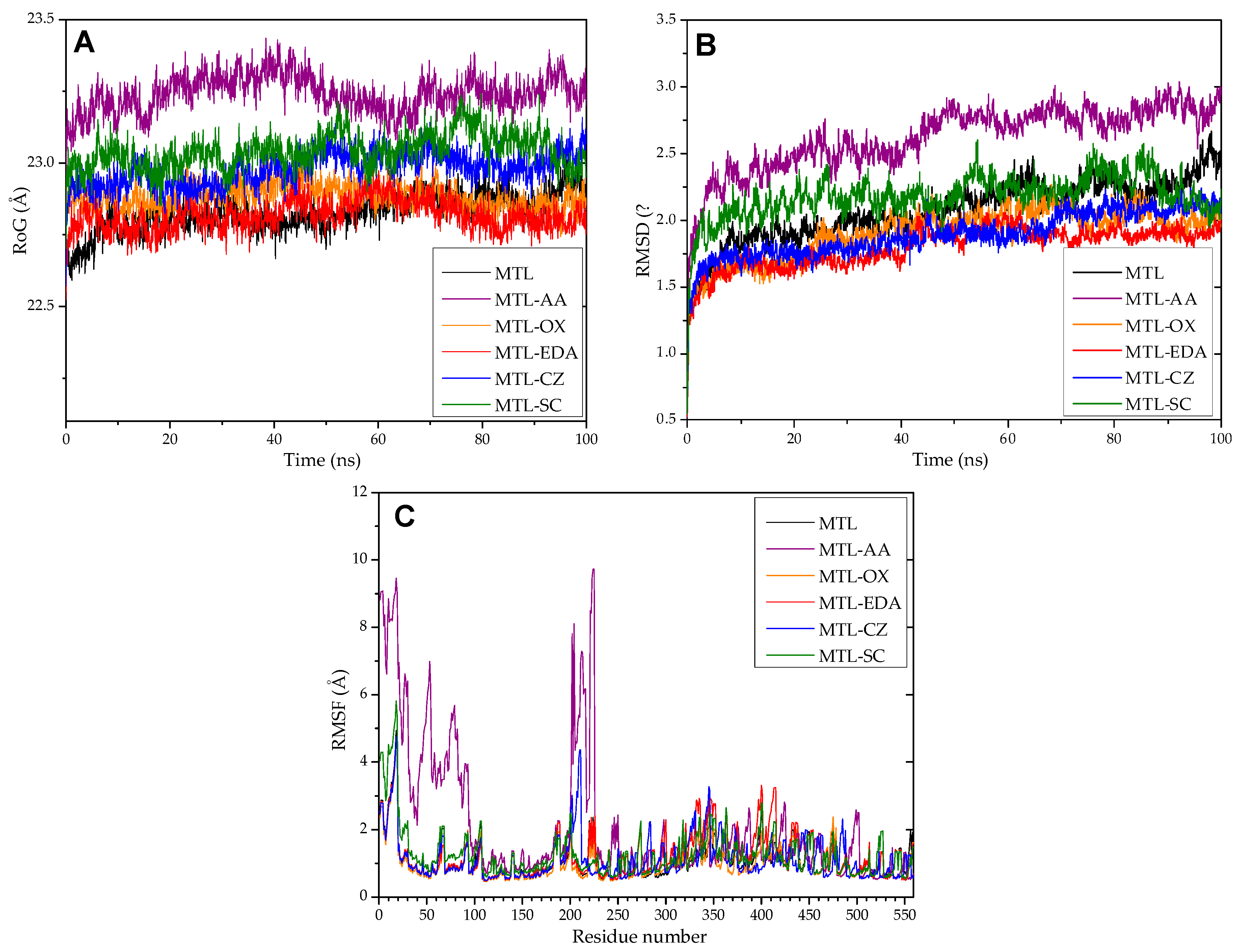

3.12. Molecular Dynamics and Molecular Docking Studies of Modified Enzymes

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | Adipic acid dihydrazide |

| ABTS | 2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| CZ | Carbohydrazide |

| EDA | Ethylenediamine |

| MD | Molecular dynamics |

| MTL | Myceliophthora thermophila laccase |

| OX | Oxalyl dihydrazide |

| PDB | Protein Data Bank |

| RoG | Radius of gyration |

| RMSD | Root mean square deviation |

| RMSF | Root mean square fluctuation |

| SC | Succinyl dihydrazide |

| T1 | Type 1 copper center |

| THF | Tetrahydrofuran |

| TLL | Thermomyces lanuginosus lipase |

References

- Sheldon, R.A. Green Chemistry and Biocatalysis: Engineering a Sustainable Future. Catal. Today 2024, 431, 114571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, C.A.; Pardo-Tamayo, J.S.; Barbosa, O. Microbial Lipases and Their Potential in the Production of Pharmaceutical Building Blocks. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoy, C.A. New Strategy for the Immobilization of Lipases on Glyoxyl–Agarose Supports: Production of Robust Biocatalysts for Natural Oil Transformation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayolo-Deloisa, K.; González-González, M.; Rito-Palomares, M. Laccases in Food Industry: Bioprocessing, Potential Industrial and Biotechnological Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghaee, M.; Salehipour, M.; Rezaei, S.; Mogharabi-Manzari, M. Bioremediation of Organic Pollutants by Laccase-Metal–Organic Framework Composites: A Review of Current Knowledge and Future Perspective. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 406, 131072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, B.B.; Rios, N.S.; Zanatta, G.; Pessela, B.C.; Gonçalves, L.R.B. Aminated Laccases Can Improve and Expand the Immobilization Protocol on Agarose-Based Supports by Ion Exchange. Process Biochem. 2023, 133, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellés Vidal, L.; Isalan, M.; Heap, J.T.; Ledesma-Amaro, R. A Primer to Directed Evolution: Current Methodologies and Future Directions. RSC Chem. Biol. 2023, 4, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagar, A.D.; Patil, M.D.; Flood, D.T.; Yoo, T.H.; Dawson, P.E.; Yun, H. Recent Advances in Biocatalysis with Chemical Modification and Expanded Amino Acid Alphabet. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 6173–6245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, P.; Pagar, A.D.; Patil, M.D.; Yun, H. Chemical Modification of Enzymes to Improve Biocatalytic Performance. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 53, 107868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roda, S.; Fernandez-Lopez, L.; Benedens, M.; Bollinger, A.; Thies, S.; Schumacher, J.; Coscolín, C.; Kazemi, M.; Santiago, G.; Gertzen, C.G.W.; et al. A Plurizyme with Transaminase and Hydrolase Activity Catalyzes Cascade Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202207344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, S.; Santiago, G.; Cea-Rama, I.; Fernandez-Lopez, L.; Coscolín, C.; Modregger, J.; Ressmann, A.K.; Martínez-Martínez, M.; Marrero, H.; Bargiela, R.; et al. Genetically Engineered Proteins with Two Active Sites for Enhanced Biocatalysis and Synergistic Chemo- and Biocatalysis. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abellanas-Perez, P.; Carballares, D.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Rocha-Martin, J. Glutaraldehyde Modification of Lipases Immobilized on Octyl Agarose Beads: Roles of the Support Enzyme Loading and Chemical Amination of the Enzyme on the Final Enzyme Features. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 248, 125853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Llamero, C.; García-García, P.; Señoráns, F.J. Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates and Their Application in Enzymatic Pretreatment of Microalgae: Comparison Between CLEAs and Combi-CLEAs. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 794672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arana-Peña, S.; Carballares, D.; Morellon-Sterling, R.; Rocha-Martin, J.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. The Combination of Covalent and Ionic Exchange Immobilizations Enables the Coimmobilization on Vinyl Sulfone Activated Supports and the Reuse of the Most Stable Immobilized Enzyme. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 199, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrego, A.H.; Romero-Fernández, M.; Millán-Linares, M.D.C.; Yust, M.D.M.; Guisán, J.M.; Rocha-Martin, J. Stabilization of Enzymes by Multipoint Covalent Attachment on Aldehyde-Supports: 2-Picoline Borane as an Alternative Reducing Agent. Catalysts 2018, 8, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanson, G.T. Chapter 22—Enzyme Modification and Conjugation. In Bioconjugate Techniques, 3rd ed.; Hermanson, G.T., Ed.; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 951–957. ISBN 978-0-12-382239-0. [Google Scholar]

- Piapan, L.; Belloni Fortina, A.; Giulioni, E.; Larese Filon, F. Sensitization to Ethylenediamine Dihydrochloride in Patients with Contact Dermatitis in Northeastern Italy from 1996 to 2021. Contact Dermat. 2024, 90, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnung, J.; Tolmachova, K.A.; Bode, J.W. Installation of Electrophiles onto the C-Terminus of Recombinant Ubiquitin and Ubiquitin-like Proteins. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kölmel, D.K.; Kool, E.T. Oximes and Hydrazones in Bioconjugation: Mechanism and Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 10358–10376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Ni, D.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Mu, W. Application of Molecular Dynamics Simulation in the Field of Food Enzymes: Improving the Thermal-Stability and Catalytic Ability. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 11396–11408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, N.; dos Santos, J.C.S.; Ortiz, C.; Barbosa, O.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Torres, R. Chemical Amination of Lipases Improves Their Immobilization on Octyl-Glyoxyl Agarose Beads. Catal. Today 2016, 259 Pt 1, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.C.; Virgen-Ortíz, J.J.; dos Santos, J.C.S.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Alcantara, A.R.; Barbosa, O.; Ortiz, C.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Immobilization of Lipases on Hydrophobic Supports: Immobilization Mechanism, Advantages, Problems, and Solutions. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37, 746–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu Silveira, E.; Moreno-Perez, S.; Basso, A.; Serban, S.; Pestana-Mamede, R.; Tardioli, P.W.; Sanchez-Farinas, C.; Castejon, N.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Rocha-Martin, J.; et al. Biocatalyst Engineering of Thermomyces lanuginosus Lipase Adsorbed on Hydrophobic Supports: Modulation of Enzyme Properties for Ethanolysis of Oil in Solvent-Free Systems. J. Biotechnol. 2019, 289, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgen-Ortíz, J.J.; Pedrero, S.G.; Fernandez-Lopez, L.; Lopez-Carrobles, N.; Gorines, B.C.; Otero, C.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Desorption of Lipases Immobilized on Octyl-Agarose Beads and Coated with Ionic Polymers after Thermal Inactivation. Stronger Adsorption of Polymers/Unfolded Protein Composites. Molecules 2017, 22, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arana-Peña, S.; Rios, N.S.; Mendez-Sanchez, C.; Lokha, Y.; Gonçalves, L.R.B.; Fernández-Lafuente, R. Use of Polyethylenimine to Produce Immobilized Lipase Multilayers Biocatalysts with Very High Volumetric Activity Using Octyl-Agarose Beads: Avoiding Enzyme Release during Multilayer Production. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2020, 137, 109535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Nilsson, L.; Lee, S.; Choi, J. Modification of EDC Method for Increased Labeling Efficiency and Characterization of Low-Content Protein in Gum Acacia Using Asymmetrical Flow Field-Flow Fractionation Coupled with Multiple Detectors. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2021, 413, 6313–6320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, H.-A.; Bourgat, Y.; Menzel, H. Optimization of Critical Parameters for Carbodiimide Mediated Production of Highly Modified Chitosan. Polymers 2021, 13, 2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Food Contact Materials, Enzymes, Flavourings and Processing Aids (CEF). Scientific Opinion on the Safety Assessment of the Substance Adipic Acid Dihydrazide, CAS No 1071-93-8, for Use in Food Contact Materials. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pardo-Tamayo, J.S.; Arteaga-Collazos, S.; Domínguez-Hoyos, L.C.; Godoy, C.A. Biocatalysts Based on Immobilized Lipases for the Production of Fatty Acid Ethyl Esters: Enhancement of Activity through Ionic Additives and Ion Exchange Supports. BioTech 2023, 12, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos-Diaz, E.; Amara, S.; Roussel, A.; Longhi, S.; Cambillau, C.; Carrière, F. Probing Conformational Changes and Interfacial Recognition Site of Lipases with Surfactants and Inhibitors. Methods Enzymol. 2017, 583, 279–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Lipase from Thermomyces lanuginosus: Uses and Prospects as an Industrial Biocatalyst. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2010, 62, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.C.; Barbosa, O.; Ortiz, C.; Berenguer-Murcia, Á.; Torres, R.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Amination of Enzymes to Improve Biocatalyst Performance: Coupling Genetic Modification and Physicochemical Tools. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 38350–38374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhuang, W.; Rabiee, H.; Zhu, C.; Deng, J.; Ge, L.; Ying, H. Amphiphilic Nanointerface: Inducing the Interfacial Activation for Lipase. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 39622–39636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdar, A.; Ismail, F.; Imran, M. Characterization of Detergent-Compatible Lipases from Candida Albicans and Acremonium Sclerotigenum under Solid-State Fermentation. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 32740–32751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quilles, J.C.J.; Brito, R.R.; Borges, J.P.; Aragon, C.C.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Bocchini-Martins, D.A.; Gomes, E.; da Silva, R.; Boscolo, M.; Guisan, J.M. Modulation of the Activity and Selectivity of the Immobilized Lipases by Surfactants and Solvents. Biochem. Eng. J. 2015, 93, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Perez, S.; Ghattas, N.; Filice, M.; Guisan, J.M.; Fernandez-Lorente, G. Dramatic Hyperactivation of Lipase of Thermomyces lanuginosa by a Cationic Surfactant: Fixation of the Hyperactivated Form by Adsorption on Sulfopropyl-Sepharose. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2015, 122, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayne, C.K.; Yumerefendi, H.; Cao, L.; Gauer, J.W.; Lafferty, M.J.; Kuhlman, B.; Erie, D.A.; Neher, S.B. We FRET So You Don’t Have To: New Models of the Lipoprotein Lipase Dimer. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, E.C.; Rodríguez, D.F.; Morales, N.; García, L.M.; Godoy, C.A. Novel Combi-Lipase Systems for Fatty Acid Ethyl Esters Production. Catalysts 2019, 9, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, N.; Tang, M.; Wan, S.; Jiang, Z.; Yue, Y.; Zhao, X.; Yang, J.; Huang, Z. Surface Charge Engineering of Thermomyces lanuginosus Lipase Improves Enzymatic Activity and Biodiesel Synthesis. Biotechnol. Lett. 2021, 43, 1403–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Zhu, E.; Xiong, D.; Wen, Y.; Xing, Y.; Yue, L.; He, S.; Han, N.; Huang, Z. Improving the Thermostability of Thermomyces lanuginosus Lipase by Restricting the Flexibility of N-Terminus and C-Terminus Simultaneously via the 25-Loop Substitutions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, E.; Xiang, X.; Wan, S.; Miao, H.; Han, N.; Huang, Z. Discovery of the Key Mutation Site Influencing the Thermostability of Thermomyces lanuginosus Lipase by Rosetta Design Programs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, H.A.; Jørgensen, L.J.; Bukh, C.; Piontek, K.; Plattner, D.A.; Østergaard, L.H.; Larsen, S.; Bjerrum, M.J. A Comparative Structural Analysis of the Surface Properties of Asco-Laccases. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakulinen, N.; Andberg, M.; Kallio, J.; Koivula, A.; Kruus, K.; Rouvinen, J. A near Atomic Resolution Structure of a Melanocarpus albomyces Laccase. J. Struct. Biol. 2008, 162, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forde, J.; Tully, E.; Vakurov, A.; Gibson, T.D.; Millner, P.; Ó’Fágáin, C. Chemical Modification and Immobilisation of Laccase from Trametes hirsuta and from Myceliophthora thermophila. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2010, 46, 430–437, Corrigendum in Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2010, 47, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.M.; Sanromán, Á.; Moldes, D. Laccase Multi-Point Covalent Immobilization: Characterization, Kinetics, and Its Hydrophobicity Applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danait-Nabar, S.; Singhal, R.S. Chemical Modification of Laccase Using Phthalic and 2-Octenyl Succinic Anhydrides: Enzyme Characterization, Stability, and Its Potential for Clarification of Cashew Apple Juice. Process Biochem. 2022, 122, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.C.; Shi, J. Modifying Surface Charges of a Thermophilic Laccase Toward Improving Activity and Stability in Ionic Liquid. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 880795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwagu, T.N.; Okolo, B.; Aoyagi, H.; Yoshida, S. Chemical Modification with Phthalic Anhydride and Chitosan: Viable Options for the Stabilization of Raw Starch Digesting Amylase from Aspergillus carbonarius. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 99, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Xu, S.; Hu, C. The Roles of H2O/Tetrahydrofuran System in Lignocellulose Valorization. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamal Pasha, M.; Rahim, M.; Dai, L.; Liu, D.; Du, W.; Guo, M. Comparative Study of a Two-Step Enzymatic Process and Conventional Chemical Methods for Biodiesel Production: Economic and Environmental Perspectives. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 489, 151254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, S.; Haider, W.; Abbas, M.; Liaqat, I.; Mumtaz, A.; Saba, I.; Farooq, M.; Safi, S.Z.; Syed-Hassan, S.S.A.; Arshad, M. Role of Laccases to Achieve Net Zero Carbon Emissions. In Enzymes in Textile Processing: A Climate Changes Mitigation Approach: Textile Industry, Enzymes, and SDGs; Arshad, M., Ed.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 191–222. ISBN 978-981-97-8058-7. [Google Scholar]

- Remonatto, D.; de Oliveira, J.V.; Guisan, J.M.; de Oliveira, D.; Ninow, J.; Fernandez-Lorente, G. Production of FAME and FAEE via Alcoholysis of Sunflower Oil by Eversa Lipases Immobilized on Hydrophobic Supports. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2018, 185, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, R.C.; Godoy, C.A.; Volpato, G.; Ayub, M.A.Z.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Guisan, J.M. Immobilization–Stabilization of the Lipase from Thermomyces lanuginosus: Critical Role of Chemical Amination. Process Biochem. 2009, 44, 963–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ren, D.; Jiang, S.; Yu, H.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W. The Study of Laccase Immobilization Optimization and Stability Improvement on CTAB-KOH Modified Biochar. BMC Biotechnol. 2021, 21, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, O.; Zor, T. Linearization of the Bradford Protein Assay. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2010, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, R.R. A Brief Practical Review of Size Exclusion Chromatography: Rules of Thumb, Limitations, and Troubleshooting. Protein Expr. Purif. 2018, 150, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, R. [38] The Rapid Determination of Amino Groups with TNBS. In Methods in Enzymology; Enzyme Structure, Part B; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1972; Volume 25, pp. 464–468. [Google Scholar]

- Spellman, D.; McEvoy, E.; O’Cuinn, G.; FitzGerald, R.J. Proteinase and Exopeptidase Hydrolysis of Whey Protein: Comparison of the TNBS, OPA and pH Stat Methods for Quantification of Degree of Hydrolysis. Int. Dairy J. 2003, 13, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of Structural Proteins during the Assembly of the Head of Bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, A.B.; Dobson, E.T.A.; Rueden, C.T.; Tomancak, P.; Jug, F.; Eliceiri, K.W. The ImageJ Ecosystem: Open-source Software for Image Visualization, Processing, and Analysis. Protein Sci. Publ. Protein Soc. 2021, 30, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nini, L.; Sarda, L.; Comeau, L.C.; Boitard, E.; Dubès, J.P.; Chahinian, H. Lipase-Catalysed Hydrolysis of Short-Chain Substrates in Solution and in Emulsion: A Kinetic Study. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2001, 1534, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.; Rempala, G.A.; Kim, J.K. Beyond the Michaelis-Menten Equation: Accurate and Efficient Estimation of Enzyme Kinetic Parameters. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, A.; Choudhary, G.; Thakur, I.S. Characterization of Laccase Activity Produced by Cryptococcus Albidus. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 42, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelbert, M.; Pereira, C.S.; Daronch, N.A.; Cesca, K.; Michels, C.; de Oliveira, D.; Soares, H.M. Laccase as an Efficacious Approach to Remove Anticancer Drugs: A Study of Doxorubicin Degradation, Kinetic Parameters, and Toxicity Assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 409, 124520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesakumar, N.; Sethuraman, S.; Krishnan, U.M.; Rayappan, J.B.B. Non-Linearization of Modified Michaelis-Menten Kinetics. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 2014, 11, 2596–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Godoy, C.A.; Mendes, A.A.; Lopez-Gallego, F.; Grazu, V.; Rivas, B.d.L.; Palomo, J.M.; Hermoso, J.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Guisan, J.M. Solid-Phase Chemical Amination of a Lipase from Bacillus thermocatenulatus to Improve Its Stabilization via Covalent Immobilization on Highly Activated Glyoxyl-Agarose. Biomacromolecules 2008, 9, 2553–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoy, C.A.; de las Rivas, B.; Guisán, J.M. Site-Directing an Intense Multipoint Covalent Attachment (MCA) of Mutants of the Geobacillus thermocatenulatus Lipase 2 (BTL2): Genetic and Chemical Amination plus Immobilization on a Tailor-Made Support. Process Biochem. 2014, 49, 1324–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, S.; Cui, D.; Sun, H.; Liu, C.; Li, L.; Zhao, M. The Biodegradation of Indigo Carmine by Bacillus Safensis HL3 Spore and Toxicity Analysis of the Degradation Products. Molecules 2022, 27, 8539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzozowski, A.M.; Savage, H.; Verma, C.S.; Turkenburg, J.P.; Lawson, D.M.; Svendsen, A.; Patkar, S. Structural Origins of the Interfacial Activation in Thermomyces (Humicola) lanuginosa Lipase. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 15071–15082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Land, H.; Humble, M.S. YASARA: A Tool to Obtain Structural Guidance in Biocatalytic Investigations. In Protein Engineering: Methods and Protocols; Bornscheuer, U.T., Höhne, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 43–67. ISBN 978-1-4939-7366-8. [Google Scholar]

- Datta Darshan, V.M.; Arumugam, N.; Almansour, A.I.; Sivaramakrishnan, V.; Kanchi, S. In Silico Energetic and Molecular Dynamic Simulations Studies Demonstrate Potential Effect of the Point Mutations with Implications for Protein Engineering in BDNF. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 271, 132247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Acevedo, C.; Flores-Gaspar, A.; Scotti, L.; Mendonça-Junior, F.J.B.; Scotti, M.T.; Coy-Barrera, E. Identification of Kaurane-Type Diterpenes as Inhibitors of Leishmania Pteridine Reductase I. Molecules 2021, 26, 3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Enzyme | Modifier | Abbr. | Modification (%) | Recover Protein (%) | Recover Activity (%) | Specific Activity (IU/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermomyces lanuginosus lipase (TLL) | - | TLL a | - | 87.3 ± 0.2 | 90.0 ± 0.4 | 9.4 ± 0.2 |

| Ethylenediamine (EDA) | TLL-EDA | 47.1 ± 0.2 | 48.4 ± 1.0 | 29.4 ±3.4 | 5.9 ± 0.5 | |

| Carbohydrazide (CZ) | TLL-CZ | 57.1 ± 1.2 | 85.0 ± 1.4 | 128.6 ± 5.7 | 14.7 ± 0.4 | |

| Oxalyl hydrazide (OX) | TLL-OX | 53.2 ± 3.6 | 68.5 ± 2.1 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | |

| Succinic dihydrazide (SC) | TLL-SC | 45.7 ± 0.9 | 98.1 ± 3.1 | 123.5 ± 2.8 | 12.2 ± 0.3 | |

| Adipic acid dihydrazide (AA) | TLL-AA | 66.0 ± 0.3 | 83.7 ± 1.7 | 159.8 ± 3.8 | 18.6 ± 0.6 | |

| Myceliophthora thermophila laccase (MTL) | - | MTL a | - | 69.4 ± 0.4 | 95.2 ± 4.9 | 1.5 ± 0.3 |

| Ethylenediamine (EDA) | MTL-EDA | 44.6 ± 1.9 | 66.4 ± 0.6 | 186.3 ± 6.3 | 4.4 ± 0.2 | |

| Carbohydrazide (CZ) | MTL-CZ | 16.2 ± 0.8 | 95.1 ± 1.5 | 23.2 ± 2.8 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | |

| Oxalyl hydrazide (OX) | MTL-OX | 54.2 ± 3.1 | 85.7 ± 0.2 | 122.4 ± 5.7 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | |

| Succinic dihydrazide (SC) | MTL-SC | 41.9 ± 0.7 | 64.6 ± 0.4 | 231 ± 6.1 | 5.6 ± 0.2 | |

| Adipic acid dihydrazide (AA) | MTL-AA | 40.6 ± 1.2 | 71.0 ± 1.0 | 389 ± 2.9 | 8.6 ± 0.2 |

| Enzyme | kcat (s−1) | km (mM) | kcat/km (mM−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLL | 70.1 ± 7.5 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 55.6 ± 8.2 |

| TLL-EDA | 42.4 ± 2.6 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 44.6 ± 3.2 |

| TLL-CZ | 98.0 ± 8.4 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 138.0 ± 9.1 |

| TLL-OX | 8.9 ± 0.9 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 7.3 ± 1.7 |

| TLL-SC | 100.4 ± 9.4 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 90.5 ± 7.1 |

| TLL-AA | 78.0 ± 5.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 75.0 ± 6.3 |

| Enzyme | Docking Scores (kJ/mol)—Enzyme with CTAB | Standard Deviation (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| TLL | −60.1 | 1.0 |

| TLL-EDA | −51.8 | 0.2 |

| TLL-CZ | −76.9 | 1.0 |

| TLL-OX | −76.9 | 0.7 |

| TLL-SC | −71.0 | 0.5 |

| TLL-AA | −67.7 | 0.8 |

| Enzyme | kcat (s−1) | km (μM) | kcat/km (μM−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MTL | 6.5 ± 0.5 | 12.2 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.2 |

| MTL-EDA | 6.1 ± 0.3 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.1 |

| MTL-CZ | 4.1 ± 1.1 | 8.7 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.2 |

| MTL-OX | 22.7 ± 9.1 | 11.1 ± 0.7 | 2.1 ± 0.8 |

| MTL-SC | 6.7 ± 0.6 | 8.5 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.2 |

| MTL-AA | 13.1 ± 0.4 | 6.2 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.2 |

| Enzyme | Score Ligand-Receptor (kJ/mol) | Standard Deviation (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| MTL | −110.6 | 1.0 |

| MTL-EDA | −141.3 | 5.4 |

| MTL-CZ | −103.0 | 0.6 |

| MTL-OX | −120.6 | 0.9 |

| MTL-SC | −132.6 | 0.4 |

| MTL-AA | −173.5 | 2.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pardo-Tamayo, J.S.; Muñoz-Vega, M.C.; Alférez, O.L.; Guerrero-Tobar, E.L.; Herrera-Acevedo, C.; Coy-Barrera, E.; Godoy, C.A. Chemical Modification of Thermomyces lanuginosus Lipase and Myceliophthora thermophila Laccase Using Dihydrazides: Biochemical Characterization and In Silico Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11094. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211094

Pardo-Tamayo JS, Muñoz-Vega MC, Alférez OL, Guerrero-Tobar EL, Herrera-Acevedo C, Coy-Barrera E, Godoy CA. Chemical Modification of Thermomyces lanuginosus Lipase and Myceliophthora thermophila Laccase Using Dihydrazides: Biochemical Characterization and In Silico Studies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(22):11094. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211094

Chicago/Turabian StylePardo-Tamayo, Juan S., Maria Camila Muñoz-Vega, Oscar L. Alférez, Evelyn L. Guerrero-Tobar, Chonny Herrera-Acevedo, Ericsson Coy-Barrera, and César A. Godoy. 2025. "Chemical Modification of Thermomyces lanuginosus Lipase and Myceliophthora thermophila Laccase Using Dihydrazides: Biochemical Characterization and In Silico Studies" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 22: 11094. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211094

APA StylePardo-Tamayo, J. S., Muñoz-Vega, M. C., Alférez, O. L., Guerrero-Tobar, E. L., Herrera-Acevedo, C., Coy-Barrera, E., & Godoy, C. A. (2025). Chemical Modification of Thermomyces lanuginosus Lipase and Myceliophthora thermophila Laccase Using Dihydrazides: Biochemical Characterization and In Silico Studies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(22), 11094. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211094