Abstract

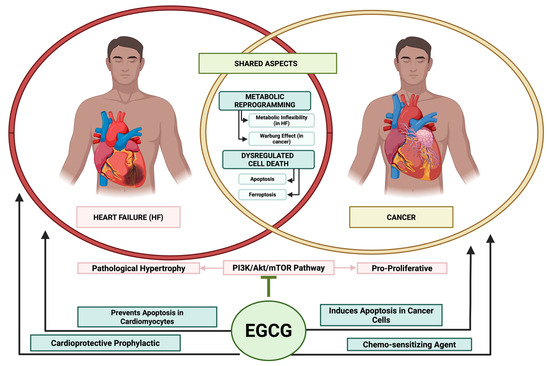

The global burden of heart failure (HF) continues to escalate, with a lifetime risk approaching one in four adults in the United States. Concurrently, advances in cancer therapeutics have created a burgeoning population of long-term survivors, who now face the significant morbidity and mortality of chemotherapy-induced cardiovascular disease (CVD). This review addresses the critical overlap of these two pathologies, which share fundamental drivers such as oxidative stress, inflammation, and metabolic dysregulation. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), the most abundant and biologically active polyphenol in green tea, has demonstrated pleiotropic bioactivity in preclinical models, encompassing potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic properties. The central aim of this review is to provide a critical and comprehensive synthesis of the evidence supporting EGCG’s dual protective role. This review dissects its molecular mechanisms in modulating key pathways in HF and cardio-oncology, evaluates its translational potential, and importantly, delineates the significant gaps that must be addressed for its clinical application. This analysis uniquely positions EGCG not merely as a nutraceutical, but as a multi-target molecular therapeutic capable of simultaneously addressing the convergent pathological cascades of heart failure and cancer-related cardiotoxicity. The synthesis of preclinical evidence with a critical analysis of its translational barriers offers a novel perspective and a strategic roadmap for future research.

Keywords:

epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG); catechins; green tea (Camellia sinensis); heart failure (HF); cardiomyopathy; myocardial infarction (MI); chemotherapy-induced cardiovascular disease; oxidative stress; Nrf2–Keap1 pathway; inflammation; fibrosis; mitochondrial dysfunction; apoptosis; autophagy; cardiac arrhythmia 1. Introduction

Heart failure (HF) remains a major public health crisis with a profound impact on global morbidity, mortality, and economic stability [1]. In the United States, approximately 6.7 million adults over the age of 20 live with heart failure, a figure projected to rise to 8.7 million by 2030, 10.3 million by 2040, and a staggering 11.4 million by 2050 [2]. The lifetime risk of developing HF has increased to 24%, meaning that approximately one in four individuals will experience this condition in their lifetime [3]. A concerning demographic shift is underway, with a disproportionate increase in the prevalence and mortality of HF observed among younger adults (35–64 years) and certain racial and ethnic groups, particularly Black and Hispanic individuals, who demonstrate higher incidence and mortality rates compared to other populations [4]. This rising disease burden is compounded by a dramatic economic cost; annual cardiovascular healthcare costs are projected to almost quadruple between 2020 and 2050 [5].

Concurrently, the therapeutic landscape of HF has evolved considerably. The introduction of sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors has provided significant improvements in morbidity and mortality across HF subtypes, redefining standard of care [6]. These agents have been shown to reduce clinical events with early and sustained benefits regardless of ejection fraction, diabetic status, or care setting. Originally developed for type 2 diabetes, SGLT2 inhibitors (also known as “flosins”) have revolutionized HF management and are now considered a core component of modern foundational therapy. Their primary mechanism involves reducing glucose and sodium reabsorption in the proximal renal tubule, leading to glycosuria, osmotic diuresis, and favorable hemodynamic effects. Beyond these actions, they exert pleiotropic effects, including modulation of oxidative stress, inflammation, and endothelial function. Large multicenter trials consistently demonstrate reductions in HF hospitalizations across the spectrum of systolic function, underscoring their broad clinical applicability. Clinicians should therefore be familiar with their use and potential adverse effects to optimize patient outcomes.

Similarly, novel nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists such as finerenone have shown promise in improving both cardiovascular and renal outcomes, further broadening treatment strategies [7]. A recent meta-analysis encompassing more than 19,000 patients from pivotal RCTs (FIDELIO-DKD, FIGARO-DKD, and FINEARTS-HF) demonstrated a 20% reduction in HF hospitalization risk (HR 0.80, 95% CI: 0.72–0.90) and a 14% reduction in all-cause mortality (RR 0.86, 95% CI: 0.77–0.97) with finerenone, though effects on cardiovascular death and renal failure require further clarification. Hyperkalemia remains the most notable adverse effect. These findings highlight finerenone’s potential role in reshaping long-term HF and CKD management, complementing established therapies.

At the same time, the field of cardio-oncology has emerged as a vital discipline, addressing the cardiovascular consequences of cancer and its treatments [8]. As cancer survival rates have improved over the past several decades, the long-term cardiotoxic effects of life-saving therapies, such as anthracyclines and targeted agents, are increasingly recognized as a major contributor to long-term morbidity and mortality in cancer survivors [9].

Chemotherapy-related cardiac dysfunction is increasingly recognized, with an overall pooled incidence of 63.21 per 1000 person-years [10]. The risk varies by agent and regimen: anthracyclines may cause cardiotoxicity in up to 48% of patients at higher cumulative doses [11], while trastuzumab, especially when combined with anthracyclines, carries rates of up to 28% [12]. Against the backdrop of rising heart failure in younger populations and a growing cohort of cancer survivors, these treatment-induced complications highlight an urgent need for targeted preventive and therapeutic strategies [13,14].

At a fundamental level, the pathophysiology of chronic heart failure and cancer is not entirely distinct but is driven by a shared set of cellular and molecular alterations [15]. These shared drivers include persistent oxidative stress, chronic systemic and localized inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and metabolic reprogramming [15,16,17]. For example, cancer patients frequently experience systemic effects such as oxidative stress and inflammation, which can contribute to the development of traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension and dyslipidaemia [18]. Cancer and its treatment modalities have long been recognized to induce CV functional decline in individuals with cancer, encompassing conditions such as left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, thromboembolic diseases, and HTN [19]. The notion that these two seemingly disparate diseases share core pathological pathways provides a strong rationale for exploring multi-target therapeutic agents that can simultaneously intervene in both disease states [15].

Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), a natural polyphenol found in high concentrations in green tea, has attracted significant scientific interest due to its remarkable ability to modulate multiple intracellular signaling cascades [20,21]. This multi-target activity is highly advantageous in complex, multifactorial diseases like HF and cardio-oncology, contrasting with the single-target approach of many conventional drugs [22,23]. This review will critically examine the evidence for EGCG’s intervention in these shared pathways, aiming to bridge the gap between its known nutraceutical benefits and its potential as a pharmacological agent.

This review is structured to guide the reader from the foundational principles of EGCG to its clinical and translational future. The initial sections outline the literature search strategy and summarize EGCG’s key biochemical properties. Subsequent sections will be dedicated to a detailed, mechanistic analysis of its effects on heart failure and cardio-oncology. The final sections will provide a rigorous translational perspective, outlining current limitations and a strategic roadmap for future research.

2. Methodology

The systematic literature search was conducted across multiple scientific databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Embase. A comprehensive list of keywords was used, including “EGCG,” “green tea catechins,” “heart failure,” “cardiomyopathy,” “myocardial infarction,” “cardio-oncology,” “cardiotoxicity,” “doxorubicin,” “trastuzumab,” and “tyrosine ดรพำkinase inhibitors.” The search was limited to English language, peer-reviewed articles published between the years 2000 and 2025. The inclusion criteria specified the selection of both preclinical (in vitro and animal) and clinical studies. Exclusion criteria included non-peer-reviewed literature and studies focused on other nutraceuticals. The screening process involved an initial review of titles, followed by abstract screening, and finally, a full-text review to ensure relevance and quality. The literature selection process will be visually represented in a PRISMA-style flow diagram to ensure the transparency and reproducibility of the review’s methodology.

Animated figures presented in this manuscript are original creations developed by the authors using https://www.BioRender.com (accessed on 1 September 2025), version 2024.3, adhering to institutional licensing agreements and figure preparation guidelines, similar to the approach used in a review by Al-Kabani et al. [24]. None of the figures presented in this manuscript are copyrighted or have been replicated from external sources.

3. Chemical and Molecular Structure of Epigallocatechin Gallate

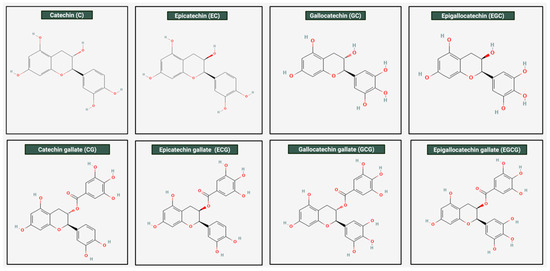

Catechins are biologically active compounds naturally found in green tea leaves (Camellia sinensis). Among them, one of the most abundant and reactive compounds is Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) [25]. The IUPAC name EGCG is [(2R,3R)-5,7-dihydroxy-2-(3,4,5-trihydroxyphenyl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-chromen-3-yl] 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoate with a molecular weight of 458.4 g/mol. EGCG is soluble in solvents such as water, ethanol, methanol, acetone, tetrahydrofuran, and pyridine [20]. Figure 1 illustrates the different molecular structures of catechins, highlighting the structural variation among these bioactive compounds.

Figure 1.

Molecular structures of catechin found in green tea. This figure illustrates the chemical structures of the different types of catechins found in green tea. As shown, all of them contain the core flavan-3-ol structure; however, variations are present. Among them, EGCG is the largest and most complex of the catechins. It has a gallate group attached to the hydroxyl group on the C-ring, an extra hydroxyl group on the B-ring, making it a “tri-hydroxy” structure instead of a di-hydroxy structure. These molecular properties, particularly the gallate group, contribute to its relatively net hydrophobic nature. EGCG is the most abundant catechin found in green tea.

4. Strategies for Isolation of Epigallocatechin Gallate from Green Tea

High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC): High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) remains the most widely applied technique for quantifying EGCG, with reversed-phase HPLC offering high sensitivity and reproducibility in separating catechins from complex matrices [26]. Recent methodological refinements, including quality-by-design approaches such as Taguchi orthogonal array design, have further improved detection limits and recovery, supporting its robustness for quantitative and translational applications [27].

One of the key advantages of HPLC is that it allows the simultaneous determination of multiple compounds with good separation performance, and its compatibility with a variety of detectors adds flexibility for different analytical needs [27,28]. However, HPLC does have limitations. Firstly, it can be time consuming and less suitable for high-throughput analysis due to long run times. In addition, HPLC presents challenges such as high operational costs, the requirement for specialized expertise, and susceptibility to contamination, which may affect reproducibility [29]. Advances such as ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) have helped overcome some of these issues by enabling faster separations (5–10 times quicker) with improved resolution compared to conventional HPLC [28].

Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC): TLC is a technique that relies on the fact that different catechins interact differently with the stationary layer and the solvent system due to their differing affinities, allowing their separation according to their molecular characteristics [30]. This method is simple and fast at separating the specific substances from their complex samples [31]. This is why TLC is widely used for the extraction of EGCG. Both conventional TLC and its advanced form, high-performance TLC (HPTLC), are considered versatile techniques capable of handling multiple samples in parallel with relatively high throughput [32]. The method is valued because it is inexpensive, simple to perform, and requires minimal instrumentation. Development times are short, and even with its straightforward setup, the technique can offer considerable sensitivity and reliable reproducibility [33]. Furthermore, the thin-layer format is advantageous when dealing with complex matrices, since it accommodates higher sample loads and allows flexible visualization and detection. TLC has key limitations as well. The method is strongly influenced by environmental factors such as humidity and the preconditioning of plates, which can introduce variability and errors [34]. Compared with HPLC, it generally provides lower resolution and poorer quantitative accuracy, restricting its use when precise separation or exact concentration measurements are required [30].

Supercritical fluid extraction (SFE): SFE commonly employs carbon dioxide as the solvent. When CO2 is pressurized above its critical point, it takes on both gas-like and liquid-like properties, allowing it to penetrate compounds efficiently and dissolve target compounds such as catechins particularly EGCG [35]. A major advantage of SFE is that it operates at relatively mild temperatures, which helps protect compounds from heat-related breakdown and preserves their biological activity [36]. The process also has short extraction times, can be carried out with little or no use of organic solvents, and causes minimal degradation [37]. SFE has practical drawbacks as well. The method requires high-pressure equipment and specialized infrastructure, which come with substantial upfront costs. These expenses make large-scale implementation in industry expensive compared to more conventional extraction techniques [36].

In summary, among the available strategies, HPLC remains the gold standard for the isolation and quantification of EGCG because of its superior resolution, reproducibility, and compatibility with multi-detector platforms, making it highly adaptable for both research and industrial settings. Nevertheless, the operational complexity and cost associated with HPLC highlight the need for ongoing methodological innovation. Future research should focus on refining UHPLC and HPTLC platforms to balance speed, throughput, and quantitative accuracy, while also exploring hybrid approaches such as coupling chromatography with mass spectrometry or capillary electrophoresis for deeper metabolite profiling. In parallel, greener and more sustainable extraction technologies, such as supercritical fluid chromatography, pressurized liquid extraction, and membrane-assisted separation, should be systematically evaluated to reduce solvent usage and improve scalability. Looking forward, the integration of miniaturized microfluidic chromatographic devices and AI-driven optimization of separation parameters represents a promising frontier, potentially enabling rapid, high-precision purification of EGCG with reduced environmental and economic burden.

5. Geographical Variations in Green Tea Species and Epigallocatechin Gallate Content

Beyond the choice of purification method, careful consideration of the inherent EGCG content across different green tea sources is equally critical, as it directly influences dosing strategies, safety margins, and the consistency of therapeutic outcomes. Table 1 shows the different types of green tea species and their respective EGCG content. Conceptualizing the EGCG content in different types of green tea leaves is crucial for assessing its potential use as a therapeutic agent, and serves as a metric for standardizing dosage, which is essential for achieving a consistent and reproducible clinical effect. Different green tea cultivars and processing methods can lead to significant inter-variation. Furthermore, accessibility also plays a role. While Korean Green Tea (Woojeon) with 105.37 mg/g has the highest EGCG content, it is less accessible compared to green tea species such as Matcha. Yet, even within Matcha there are also multiple grades (average, ceremonial, and culinary) depending on cultivation, thus carrying their own distinct EGCG content.

Moreover, storage conditions have a significant impact on the stability of EGCG. It readily undergoes oxidation and epimerization to gallocatechin gallate (GCG), processes that are accelerated by elevated temperature, neutral to alkaline pH, oxygen exposure, and light. As a result, the content of EGCG in green tea infusions or extracts stored in under-suboptimal conditions gradually decreases. Commercially prepared beverages, for example, often contain significantly lower levels of EGCG than freshly brewed tea, largely due to degradation during manufacturing and storage. Optimal preservation requires acidic environments (pH ~3–4), low temperatures (4 °C), exclusion of oxygen, and protection from light, conditions that significantly slow down degradation. These findings highlight the need to consider storage variables in both experimental designs and translational applications, as the apparent concentration and biological activity of EGCG may be underestimated if stability is not rigorously controlled [38,39,40].

Beyond issues of storage stability, the absolute EGCG content in tea leaves is equally critical, as it determines the effective therapeutic dose and ensures that potential toxicity thresholds are not exceeded. Ramachandran et al. demonstrated the effect of pure EGCG repeated doses in mice, observing dose-dependent hepatotoxicity [41].Thus, evaluation of safe EGCG concentration is vital to ensure a more patient-complaint safety profile. Lastly, population variability plays a significant role in EGCG activity. When studying the effect of extrinsic factors, such as genetics, sex, age, patient-specific factors, knowing and standardizing the EGCG content from its source is essential to ensure robust and reliable data.

Table 1.

Variation in EGCG content and bioaccessible dose among commonly consumed green teas.

Table 1.

Variation in EGCG content and bioaccessible dose among commonly consumed green teas.

| Green Tea Type | Geographical Area of Origin | Processing Method/Cultivar | EGCG Content in Dry Leaf (mg/g) | EGCG per Serving (mg) (Based on 2 g Dry Tea or Powder) | Serving Volume (mL) | EGCG Concentration per Serving (µM) | Reference | Remarks on EGCG Measurement and Brewing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Green Tea (Infusion) | Global | Various | N/A | 165 | 240 | 1499.0 | [42] | General average for brewed green tea. |

| General Green Tea (Infusion) | Global | Various | N/A | 90 | 200 | 981.7 | [43] | Based on 2.5 g tea leaves per 200 mL water. |

| General Green Tea (Dry Leaves) | Global | Various | 73.8 | 147.6 | N/A | N/A | [42] | EGCG content in dried leaves, not brewed. |

| Matcha | Japan | Powdered, Shade-grown | 50.5–56.6 (avg. ceremonial: 56.6; culinary: 50.5) | 101–113 | 100 | ~22–24 | [44] | Based on 2 g powder per cup. Consuming whole leaf. |

| Gyokuro | Japan | Shade-grown | 53.31 | 106.62 | 240 | 969.4 | [45] | EGCG in dry leaf. |

| Gyokuro (Infusion) | Japan | Shade-grown | N/A | 268.09 | 240 | 2437.0 | [45] | Infusion from 10 g leaves in 60 mL water at 60 °C for 2 min. Highly concentrated. |

| Sencha (Superior) | Japan | Sun-grown | 67.45 | 134.90 | 240 | 1226.2 | [45] | EGCG in dry leaf. |

| Sencha (Superior Infusion) | Japan | Sun-grown | N/A | 74.41 | 240 | 676.0 | [45] | Infusion from 6 g leaves in 170 mL water at 70 °C for 1 min. |

| Sencha (Standard) | Japan | Sun-grown | 62.16 | 124.32 | 240 | 1131.0 | [45] | EGCG in dry leaf. |

| Sencha (Standard Infusion) | Japan | Sun-grown | N/A | 91.30 | 240 | 830.0 | [45] | Infusion from 6 g leaves in 260 mL water at 90 °C for 1 min. |

| Sencha (Deep-Steamed) | Japan | Sun-grown, Deep-steamed | 63.51 | 127.02 | 240 | 1155.0 | [45] | EGCG in dry leaf. |

| Sencha (Deep-Steamed Infusion) | Japan | Sun-grown, Deep-steamed | N/A | 114.20 | 240 | 1038.0 | [45] | Infusion from 6 g leaves in 260 mL water at 90 °C for 1 min. |

| Sencha (Infusion) | Japan | Sun-grown | N/A | 124 mg/100 mL | 100 | 2705.4 | [46] | EGCG content per 100 mL of infusion. |

| Tamaryokucha (Pan-Fired) | Japan | Pan-fired | 64.29 | 128.58 | 240 | 1168.0 | [45] | EGCG in dry leaf. |

| Tamaryokucha (Pan-Fired Infusion) | Japan | Pan-fired | N/A | 65.72 | 240 | 597.1 | [45] | Infusion from 6 g leaves in 260 mL water at 90 °C for 1 min. |

| Tamaryokucha (Steamed) | Japan | Steamed | 61.61 | 123.22 | 240 | 1120.0 | [45] | EGCG in dry leaf. |

| Tamaryokucha (Steamed Infusion) | Japan | Steamed | N/A | 90.00 | 240 | 818.0 | [45] | Infusion from 6 g leaves in 260 mL water at 90 °C for 1 min. |

| Lu’an Guapian (HSGP) | Anhui, China (Huoshan County) | Traditional Processing | 110.69 | 221.38 | 240 | 2013.7 | [47] | EGCG in dry leaf (WT%). |

| Lu’an Guapian (JZGP) | Anhui, China (Jinzhai County) | Traditional Processing | 87.18 | 174.36 | 240 | 1585.5 | [47] | EGCG in dry leaf (WT%). |

| Lu’an Guapian (YAGP) | Anhui, China (Yu’an District) | Traditional Processing | 80.23 | 160.46 | 240 | 1459.7 | [47] | EGCG in dry leaf (WT%). |

| Lu’an Guapian (IMGP) | Anhui, China (Inner Mountain) | Traditional Processing | 92.75 | 185.50 | 240 | 1687.2 | [47] | EGCG in dry leaf (WT%). |

| Lu’an Guapian (OMGP) | Anhui, China (Outer Mountain) | Traditional Processing | 79.33 | 158.66 | 240 | 1443.5 | [47] | EGCG in dry leaf (WT%). |

| Korean Green Tea (Woojeon) | Korea | Early Plucking Period | 105.37 | 210.74 | 240 | 1916.6 | [48] | EGCG in dry leaf. |

| Korean Green Tea (Sejak) | Korea | Mid Plucking Period | 103.95 | 207.90 | 240 | 1890.3 | [48] | EGCG in dry leaf. |

| Korean Green Tea (Joongjak) | Korea | Late Plucking Period | 111.59 | 223.18 | 240 | 2030.0 | [48] | EGCG in dry leaf. |

| Korean Green Tea (Daejak) | Korea | Latest Plucking Period | 112.86 | 225.72 | 240 | 2053.3 | [48] | EGCG in dry leaf. |

| Jeju Green Tea (Steamed) | Jeju, Korea | Steaming | 24.0 (Extract) | 48.0 (Extracted) | 240 | 436.0 | [49] | EGCG extracted from dry tea into infusion (mg/g dry tea). Assumed 2 g dry tea serving. |

| Jeju Green Tea (Pan-fired) | Jeju, Korea | Pan-firing | 31.8 (Extract) | 63.6 (Extracted) | 240 | 578.0 | [49] | EGCG extracted from dry tea into infusion (mg/g dry tea). Assumed 2 g dry tea serving. |

| Jeju Green Tea (Steamed and Pan-fired, Light) | Jeju, Korea | Steaming and Pan-firing | 20.2 (Extract) | 40.4 (Extracted) | 240 | 367.0 | [49] | EGCG extracted from dry tea into infusion (mg/g dry tea). Assumed 2 g dry tea serving. |

| Jeju Green Tea (Steamed and Pan-fired, Heavy Roast) | Jeju, Korea | Steaming and Pan-firing, Heavy Roasting | 42.3 (Extract) | 84.6 (Extracted) | 240 | 769.0 | [49] | EGCG extracted from dry tea into infusion (mg/g dry tea). Assumed 2 g dry tea serving. |

| Boseong Green Tea (Pan-fired) | Boseong, Korea | Pan-firing | 39.9 (Extract) | 79.8 (Extracted) | 240 | 725.0 | [49] | EGCG extracted from dry tea into infusion (mg/g dry tea). Assumed 2 g dry tea serving. |

| Hangjou Green Tea (Pan-fired) | Hangjou, China | Pan-firing | 36.9 (Extract) | 73.8 (Extracted) | 240 | 671.0 | [49] | EGCG extracted from dry tea into infusion (mg/g dry tea). Assumed 2 g dry tea serving. |

| Shizuoka Green Tea (Steamed) | Shizuoka, Japan | Steaming | 24.5 (Extract) | 49.0 (Extracted) | 240 | 445.0 | [49] | EGCG extracted from dry tea into infusion (mg/g dry tea). Assumed 2 g dry tea serving. |

| Longjing (Dragon Well) | Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China | Pan-fired | Variable | Variable | 240 | Variable | [50] | Known for high thiamine; EGCG present but specific values per serving not consistently provided. |

| Biluochun (Green Snail Spring) | Jiangsu, China | Traditional Processing | Variable | Variable | 240 | Variable | [50] | Rich in polyphenols, high antioxidant level. Specific EGCG per serving not provided. |

| Huangshan Maofeng | Anhui, China | Traditional Processing | Variable | Variable | 240 | Variable | [50] | Rich in antioxidants, including EGCG, but specific values per serving not provided. |

6. Determinants of Epigallocatechin Gallate Bioavailability and Absorption

6.1. Metabolic Barriers to Epigallocatechin Gallate Bioavailability

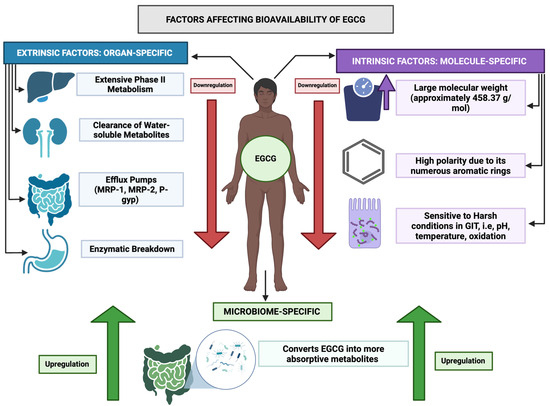

EGCG demonstrates poor oral bioavailability, largely due to rapid clearance and extensive phase II metabolism occurring primarily in the intestine and liver [20]. Figure 2 highlights the different factors affecting the absorption, accumulation, and bioavailability of EGCG.

Figure 2.

Overview of factors affecting bioavailability of EGCG. This figure highlights the different factors affecting the absorption, accumulation, and bioavailability of EGCG from the human GIT to target cells. There are certain factors that correspond to the EGCG molecule itself—molecular weight, polarity, and chemical instability; these aspects make it less ideal of a molecule to be passively absorbed along the size-selective, lipophilic phosphodiester bilayer of the enterocytes. In addition, factors such as liver’s first pass metabolism, fast clearance by the renal system, efflux mechanism in the GIT, and enzymatic breakdown in the gut further reduce EGCG’s bioavailability in the human tissues. However, the gut microbiome is one factor present in the human colon that allows EGCG to be absorbed more readily. Via microbiome-mediated enzymatic processes, it allows EGCG to be molecularly changed to facilitate its passive diffusion across the human gut.

After absorption, EGCG undergoes methylation, sulfation, and glucuronidation, processes which markedly reduce the concentration of free, bioactive EGCG available in systemic circulation [25]. These conjugated metabolites are generally more water-soluble and readily excreted, which further decreases overall bioavailability. Importantly, metabolic conjugation lowers systemic exposure to the parent EGCG compound and alters biological activity; although some conjugates retain partial antioxidant properties, they are usually less potent than free EGCG. From a therapeutic standpoint, this extensive metabolism is not ideal, as the most robust bioactivity appears to come from unmetabolized EGCG [25]. Therefore, to optimize its translational potential, strategies to enhance the stability of free EGCG, such as through nano-formulations or chemical modifications, are warranted.

6.2. Microbiome-Associated Epigallocatechin Gallate Pharmacokinetics and Absorption

The gut microbiome has a major pharmacokinetic significance in EGCG metabolism in the human gut. Table 2 highlights the representative microbiota involved in metabolic processing of EGCG in the body along with their biological relevance.

Table 2.

Gut microbiota-mediated metabolism of EGCG.

Only a small fraction of dietary polyphenols is absorbed in the small intestine; most bypass it and reach the colon, where the microbial community plays a central role in their metabolism [56]. The microbiome-driven transformations of EGCG occur through the following five major processes: degalloylation, ring fissure, dehydrogenation, hydroxylation, and carboxylation, each of which critically shapes its pharmacokinetic journey. Using ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography coupled with hybrid quadrupole Orbitrap mass spectrometry (UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap-MS), Liu et al. demonstrated that EGCG undergoes sequential microbial degradation, including ester hydrolysis, C-ring opening, A-ring fission, dehydroxylation, and aliphatic chain shortening, ultimately yielding smaller, bioactive metabolites [51].

One of the key steps is degalloylation, mediated by esterases of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, which produces epigallocatechin (EGC) and gallic acid (GA). This process not only facilitates the absorption of EGC but also liberates GA locally, where it exerts anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects [57]. GA has shown cardioprotective benefits in multiple models; Jin et al. demonstrated improved outcomes in a pressure overload-induced HF mouse model and rat cardiac fibroblasts [58], while Badavi et al. reported enhanced activity of scavenging enzymes such as lactate dehydrogenase, superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase in a Wistar rat myocardial infarction (MI) model [59]. These findings were corroborated by Priscilla et al., who showed that GA reduced oxidative stress in isoproterenol-induced MI [60]. Thus, microbial production of GA from EGCG illustrates how beneficial effects can arise even before the parent compound reaches target tissues.

EGC itself, though less potent than EGCG, also contributes to antioxidant defense. He et al. showed that catechins, including EGC, mitigated H2O2-induced cell damage in HT22 cells, improving viability and reducing ROS levels, as confirmed by flow cytometry [61]. The presence of a pyrogallol group on the C-ring of EGC underlies its ability to scavenge ROS [62]. Together, these data suggest that both EGCG and its microbial metabolites extend protective antioxidant functions relevant to HF.

Other transformations, including dehydrogenation and reduction in the A- and B-rings, generate phenylpropionic and phenylacetic acids [51]. These smaller molecules diffuse readily across enterocyte membranes, increasing systemic absorption. Importantly, phenylpropionic acid also exhibits antioxidant activity, as confirmed by visible spectroscopy, which shows that hydroxyl substitutions on the aromatic ring enhance its radical-scavenging capacity [63]. Ultimately, EGCG metabolism yields end-products that are excreted in urine through the combined activity of mixed microbiota, which may serve as useful biomarkers of microbiota-driven pharmacokinetics [20,64].

The breakdown from the parent compound EGCG to its smaller active metabolites does influence its bioavailability and cellular activity, hence the microbiome profile and inter-individual differences amount populations which may significantly influence EGCG uptake metabolite-formation. Researchers refer to these as “gut metabotypes” op-r “gut microbiota-associated metabotypes” [65].

Case in point—Liu et al. observed these so-called gut metabotypes. Differences in metabolite profiles—such as gallic acid, pyrogallol, phenylpropane-2-ols, and phenyl-γ-valerolactones—were directly correlated with the abundance of specific microbial taxa identified via 16S rRNA sequencing [66]. Importantly, gut dysbiosis is linked to clinical conditions including cancer and cardiovascular disease, which may further change the metabolic fate of EGCG. This interaction emphasizes the necessity of considering the microbiota as a potential modulator of EGCG’s therapeutic effects in addition to its role as a metabolic barrier. Therefore, to assess EGCG pharmacokinetic and absorption and its further development as a therapeutic agent, gut metabotypes must be considered.

In summary, EGCG escapes small-intestinal absorption and undergoes microbiota-driven biotransformations (degalloylation, ring/C-ring fission, dehydroxylation, reduction, chain shortening) that generate bioactive metabolites (e.g., EGC, GA, phenylpropionic/phenylacetic acids, γ-valerolactones). Because these metabolites materially contribute to systemic exposure and effect, inter-individual “gut metabotypes” and dysbiosis become key determinants of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic variability.

Considering the evidence presented, future work should advance from a compound-centric approach toward a systems pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) framework, integrating metagenomics, targeted and untargeted metabolomics, and lipidomics with physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models of the gut–liver axis. Stable-isotope–resolved metabolomics (SIRM) [67], employing uniformly 13C-labeled EGCG and 13C-gallic acid could be particularly valuable in resolving metabolite origin and carbon flux into GA, pyrogallol, phenyl-γ-valerolactones, phenylpropionates, and hippurate. Such studies should be coupled with high-resolution UHPLC-HRMS/MS workflows [68], using parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) [69] and data-independent acquisition (DIA) [70], to enable absolute quantitation of EGCG conjugates generated through UGT, SULT, and COMT activity, as well as transporter-dependent excretion mediated by ABCG2/BCRP, ABCB1/P-gp, and ABCC2/MRP2. Another critical area will be the definition of microbiota-associated metabotypes, using unsupervised clustering of metabolite ratio features (for example, Σvalerolactones/GA, GA-sulfate/GA-glucuronide, or valerolactone-glucuronides/valerolactone-sulfates), which can be mechanistically linked to taxa-level enzyme capacities such as esterases, reductases, and dehydroxylases. These associations should then be validated by employing anaerobic gnotobiotic consortia and CRISPR-edited strains of relevant bacteria, including Flavonifractor, Eggerthella, and Bifidobacterium [71,72,73]. Parallel efforts must also address the contribution of host lipidomics [74], with both shotgun and targeted approaches required to quantify how bile-salt pools, mixed micelles, and phospholipid composition [75] determine luminal solubilization and enterocyte uptake of EGCG and its metabolites [76]. Likewise, profiling of microbial-derived short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and secondary bile acids using LC-MS/MS and GC-MS [77] will provide insight into their role as regulators of transporter expression (e.g., OATP1A2/2B1, SLC22 family, MCTs), and efflux systems (BCRP, P-gp, MRPs) [78] as well as their influence on intestinal barrier integrity [79].

To experimentally capture these dynamics under physiologically relevant conditions, microphysiological systems should be prioritized. Anaerobic gut-on-chip models co-cultured with defined microbial consortia, when coupled with liver-on-chip platforms [80], offer the potential to parameterize intestinal and hepatic clearance, as well as conjugation kinetics, under authentic bile-acid and lipid milieus. Such systems can be complemented by MALDI mass spectrometry imaging (MALDI-MSI) to map the tissue distribution of EGCG versus gallic acid and related metabolites.

From a translational standpoint, the systematic evaluation of bioenhancer interactions represents another important research axis. For example, screening piperine, a piperidine alkaloid, and related structural scaffolds against UGT1A1/1A9, SULT1A1, COMT, and efflux transporters such as BCRP and P-gp using vesicle systems and Caco-2/MDCK transporter assays will help to establish reliable inhibition constants (Ki/IC50). These values should be integrated into PBPK models and drug–drug interaction (DDI) risk assessments, with subsequent validation in microbially stratified crossover trials to confirm clinical relevance.

Regional population specificity must also be addressed, particularly in Gulf-region cohorts, where dietary patterns, baseline bile-acid/lipidome composition, antibiotic exposure, and microbiome diversity [81], are likely to shape EGCG metabolism. By jointly modeling these factors, researchers can establish metabotype-aware reference intervals and dosing algorithms tailored to specific populations. In parallel, pre-analytical variables, including brewing conditions, storage pH, oxygen and light exposure, and temperature should be rigorously standardized. Reporting metabolite panels, including urinary hippurate and phenyl-γ-valeric acids, as pharmacokinetic endpoints rather than focusing exclusively on parent EGCG, would provide a more accurate reflection of systemic exposure.

Finally, advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning offer transformative potential. Multi-view variational models and graph-based networks can integrate multi-omic datasets—including metagenome, metabolome, lipidome, and transporter genotypes—to generate predictive exposure–response maps at the individual level [82]. This strategy could ultimately enable precision nutraceutical deployment of EGCG, where dosing and formulation are informed by a subject’s microbiota composition, lipidome profile, and genetic determinants of transport and metabolism.

7. Polypharmacy and Epigallocatechin Gallate–Drug Interactions

In clinical practice, polypharmacy introduces another critical variable that influences EGCG bioavailability. Table 3 illustrates the multiple drug class, their representative drugs, and consequence of EGCG bioavailability. EGCG and green tea catechins are recognized inhibitors of intestinal uptake transporters (notably OATP1A2/2B1) and modulators of efflux pumps such as P-glycoprotein (P-gp) [83]. These interactions can significantly reduce systemic exposure to co-administered drugs. For example, EGCG markedly decreases plasma concentrations of the β-blocker nadolol [84,85] and the ACE inhibitor lisinopril [86], both standard therapies in HF management, by impairing intestinal uptake. Similar transporter-mediated reductions have been documented with fexofenadine, an OATP1A2 substrate [87]. In oncology, EGCG has a particularly concerning interaction with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib, where direct chemical antagonism abolishes its cytotoxic efficacy [88].

Given these clinically relevant interactions, future research must prioritize systematic transporter–substrate mapping of EGCG and its metabolites using high-throughput in vitro assays, integrated PBPK/DDI modeling, and stratified clinical validation, to establish evidence-based guidelines for co-administration in polypharmacy settings. Case in point, in heart failure, impaired uptake of β-blockers such as nadolol or ACE inhibitors like lisinopril could compromise hemodynamic stability [86,89], while in oncology, direct antagonism of bortezomib [90,91] underscores the potential for EGCG to undermine chemotherapeutic efficacy. Addressing such scenarios requires not only mechanistic dissection of transporter and metabolic pathways but also carefully designed clinical trials that evaluate EGCG use in patients receiving cardiovascular and anticancer therapies.

Table 3.

Drugs affecting EGCG bioavailability.

Table 3.

Drugs affecting EGCG bioavailability.

| Drug Class | Representative Drugs | Indication | Mechanism of Interaction | Effect on EGCG Bioavailability | Notes/Clinical Relevance | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMT (Catechol-O-methyltransferase) Inhibitors | Entacapone, Tolcapone | Parkinson’s disease | Inhibit methylation of EGCG | ↑ Plasma EGCG levels, prolonged half life | Risk of higher systemic EGCG exposure; may increase adverse effects (e.g., hepatotoxicity) | [92] |

| UGT (UDP-glucuronosyltransferase) Inhibitors | Valproic acid | Epilepsy | Block EGCG glucuronidation in intestine/liver | ↑ Bioavailability | Drug–nutrient competition; caution with chronic use | [93,94] |

| Probenecid | Gout | |||||

| SULT (Sulfotransferase) Inhibitors | Diclofenac, Celecoxib | Inflammatory conditions, pain, arthritis | Reduce sulfation of EGCG | ↑ Systemic exposure | Possible synergy in inflammation models | [95] |

| P-gp (P-glycoprotein) Inhibitors | Verapamil | Hypertension, arrhythmias | Prevent EGCG efflux from intestinal cells | ↑ Absorption and plasma concentrations | High risk for pharmacokinetic interactions with narrow therapeutic index drugs | [96,97,98] |

| Cyclosporine | Immunosuppression | |||||

| Quinidine | Arrythmias | |||||

| OATP (Organic Anion Transporting Polypeptide) Substrates/Inhibitors | Statins | Hyperlipidemia, cardiovascular risk reduction | Competition on intestinal uptake transporters | ↓ Oral uptake of EGCG OR altered statin pharmacokinetics | EGCG may reduce statin absorption (bidirectional effect) | [99,100] |

| Rifampicin | Tuberculosis | |||||

| Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) | Omeprazole, Pantoprazole | GERD, peptic ulcers | Increase gastric pH → reduce EGCG degradation | Potential ↑ stability but ↓ solubility depending on formulation | Effect varies with formulation (capsules vs. tea extract) | [101] |

| Antibiotics (Broad Spectrum) | Ciprofloxacin, Amoxicillin–Clavulanate | Broad-spectrum bacterial infection | Disrupt gut microbiota metabolism of EGCG | ↓ Formation of valerolactone/phenolic metabolites; altered bioactivity | Reduces health benefits mediated by microbiota-derived metabolites | [102] |

| Iron Supplements | Ferrous sulfate, Ferric chloride | Iron deficiency anemia | Chelates EGCG, forming insoluble complexes | ↓ EGCG absorption | Should avoid co-administration of EGCG-rich tea with iron | [103] |

| Anticoagulants/Antiplatelets | Warfarin | Thrombosis prevention and treatment, atrial fibrillation | Not directly altering PK but EGCG itself has antiplatelet/anticoagulant properties | ↑ Bleeding risk despite bioavailability changes | Clinical safety concern | [104,105,106,107] |

| Aspirin, Clopidogrel | Cardiovascular disease prevention, antiplatelet therapy | |||||

| Protease Inhibitors (HIV Drugs) | Ritonavir, Saquinavir | HIV infections | EGCG can inhibit CYP3A4 and P-gp, altering drug PK; reciprocal effect possible | Altered absorption of both EGCG and drug | Case reports of interactions | [108] |

| β-blockers | Propranolol, Metoprolol | Hypertension, heart failure, arrythmias, angina | EGCG inhibits intestinal transport/metabolism | ↓ Bioavailability of β-blockers (drug side) | Reciprocal PK effect: EGCG may also increase systemic exposure | [109] |

8. Strategies to Enhance Bioavailability of Epigallocatechin Gallate

Given EGCG’s inherent instability and low oral bioavailability, multiple strategies have been developed to enhance systemic exposure, as shown in Table 4. Simple interventions such as administering EGCG on an empty stomach can increase absorption two- to fourfold, although fasting administration raises safety concerns related to hepatotoxicity at high doses [110]. Formulation-based approaches have demonstrated greater potential: in both preclinical and clinical investigations, phospholipid complexes (phytosomes) and nanoparticle carriers (liposomes, bilosomes, transferosomes) improve intestinal permeability and shield EGCG from pH- and enzyme-mediated degradation, leading to increased plasma concentrations [111].

The addition of ascorbic acid to formulations stabilizes EGCG by preventing oxidative degradation and simultaneously enhances absorption [112]. Experimental strategies such as pro-drug synthesis (peracetylated pro-EGCG) [113] and co-administration with metabolism inhibitors like piperine have also demonstrated improved pharmacokinetic profiles in preclinical models [114]. All these developments point to the importance of formulation science as a necessary condition for the effective translation of EGCG into clinical treatments.

A critical limitation, however, is that most bioavailability-enhancing strategies remain validated primarily in preclinical models, with limited head-to-head clinical comparisons. Ensuring translational success will require systematic evaluation of safety, scalability, and inter-individual variability, particularly given EGCG’s dose-dependent hepatotoxicity and microbiome-modulated metabolism.

Table 4.

Strategies to enhance EGCG bioavailability and pharmacokinetics.

Table 4.

Strategies to enhance EGCG bioavailability and pharmacokinetics.

| Strategy | Mechanism/Rationale | Examples/Approaches | Key Outcomes | Limitations/Considerations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoencapsulation/Nanoparticles | Protects EGCG from degradation; increases solubility and intestinal absorption | - EGCG-loaded liposomes (phospholipid vesicles) - Polymeric nanoparticles (PLGA, chitosan, PEGylated systems) - Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) | ↑ Stability in GI tract ↑ Plasma concentration Controlled release | Complexity in formulation; scale-up issues; regulatory hurdles | [115,116,117] |

| Protein/Peptide Carriers | Binding to proteins improves stability and transport across membranes | - Casein micelles - Gelatin nanoparticles - BSA–EGCG complexes | Sustained release Reduced oxidation Enhanced intestinal uptake | Allergenicity concerns (milk proteins); may alter taste | [118,119,120,121] |

| Phospholipid Complexes (Phytosomes®) | Conjugation with phospholipids enhances lipophilicity and membrane permeability | EGCG–phosphatidylcholine complexes (commercial: Greenselect® Phytosome) | 2–4× ↑ oral bioavailability Better tissue distribution | Cost; formulation stability | [122,123] |

| Co-administration with Bioenhancers | Inhibits efflux transporters and metabolic enzymes (COMT, UGTs) | - Piperine (from black pepper) - Quercetin - Ascorbic acid (vitamin C prevents auto-oxidation) | ↑ Systemic exposure Reduced EGCG glucuronidation/sulfation | Possible herb–drug interactions May alter safety profile | [20,124,125] |

| Prodrug Approaches | Mask polar groups to improve absorption, later hydrolyzed in vivo | - Esterified EGCG derivatives - Peracetylated EGCG | ↑ Lipophilicity ↑ Plasma half life | May reduce intrinsic activity; prodrug activation variability | [113] |

| Encapsulation in Polysaccharides | Protects from pH and enzymatic degradation; controlled release | - EGCG in alginate beads - Cyclodextrin inclusion complexes | Sustained colonic release Improved taste masking | Encapsulation efficiency varies; limited load capacity | [126,127] |

| Lipid-based Formulations | Enhance solubility and lymphatic transport | - Self-emulsifying drug delivery systems (SEDDS) - Nanoemulsions/microemulsions | ↑ Solubility Avoids first-pass metabolism | Stability and scalability challenges | [128] |

| Metal/Mineral Conjugates | Chelation reduces degradation; modulates transport | EGCG–Zn, EGCG–Se complexes | Enhanced antioxidant and anticancer potency Greater plasma stability | Toxicity risk if not controlled | [129,130] |

| Targeted Delivery Systems | Directs EGCG to tissues/organs of interest | - Antibody–EGCG conjugates - Folate-decorated nanoparticles (for tumor targeting) | Selective accumulation in tumors or inflamed tissue | High cost; complex validation | [131,132] |

| Controlled-release Formulations | Sustained release prevents rapid clearance | EGCG hydrogels, matrix tablets | Prolonged half life Steady plasma levels | Patient compliance; release variability | [133] |

| Microbiota-directed Strategies | Modulate gut microbiota to favor beneficial EGCG metabolites (e.g., valerolactones) | - Prebiotics/probiotics co-administration - Engineered gut bacteria | ↑ Production of bioactive metabolites Personalized nutrition approach | Still experimental; inter-individual variability | [134] |

9. Pharmacokinetics: Half-Life

EGCG demonstrates rapid gastrointestinal absorption with peak plasma concentrations within 1–2.5 h, but its therapeutic utility is limited by a short half-life (1.9–4.6 h), extensive phase-II metabolism (methylation, sulfation, glucuronidation), and <1% urinary excretion of unchanged compound, resulting in low bioavailability despite distribution into tissues, including across the blood–brain barrier. Multiple advanced formulation strategies have been developed to overcome these limitations [20]. Prodrug chemistry, exemplified by per-O-acylated derivatives such as EGCG octaacetate (Pro-EGCG), masks phenolic groups to reduce early conjugation, achieving up to 5-fold higher bioavailability, enhanced stability, and sustained therapeutic effects through enzymatic hydrolysis at target sites. Nanocarrier systems—including PLGA nanoparticles that enhance cellular uptake up to 10-fold, and PEGylated liposomes that yield 3–4 times higher plasma concentrations with selective release in acidic tumor environments, demonstrate encapsulation efficiencies of 51–97% and particle sizes < 300 nm, with ligand modifications enabling targeted delivery. Albumin-binding conjugates, such as fatty acid–EGCG derivatives, exploit FcRn-mediated recycling, with palmitic acid conjugation producing 20-fold stronger albumin binding and 5-fold longer serum half-life, paralleling clinical successes like Evans blue derivatives. Lipid-based self-emulsifying drug delivery systems (SEDDS/SMEDDS) enhance solubilization, lymphatic uptake, and membrane permeability, resulting in 2–3-fold increases in oral bioavailability in rodents. However, recent studies caution that chronic use may disrupt gut microbiota. Synergistic co-formulations using stabilizers (ascorbate, xylitol) and bioenhancers such as piperine, which increase EGCG plasma Cmax and AUC by 1.3-fold through 40% inhibition of intestinal glucuronidation, provide dose-sparing benefits and sustained tissue exposure. Recent advances in hybrid delivery systems, including nanoparticle-in-liposome constructs, prodrug-loaded nanocarriers, and stimuli-responsive carriers (pH-, enzyme-, and temperature-sensitive platforms, as well as cell-penetrating peptides for blood–brain barrier penetration) have shown preclinical promise, though translation is challenged by interindividual metabolic variability, off-target risks, and manufacturing standardization. Collectively, these innovations represent a paradigm shift toward precision delivery systems that simultaneously stabilize EGCG, extend its half-life, and optimize parent–metabolite exposure for diverse clinical applications.

10. Molecular Pathways in Heart Failure: Targets for EGCG

10.1. Oxidative Stress, Keap1–Nrf2 Antioxidant Defense, and Therapeutic Potential of Epigallocatechin Gallate

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), including superoxide anions, hydroxyl radicals, and hydrogen peroxide, arise from normal cellular metabolism—primarily mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and enzymes such as NADPH oxidase, xanthine oxidase, and nitric oxide synthase [135,136,137,138]. While low levels of ROS function as secondary messengers in physiological signaling [139,140], excessive accumulation disrupts redox homeostasis, induces oxidative stress, and damages DNA, lipids, and proteins [135,137,139]. This redox imbalance is particularly harmful in cardiomyocytes due to their high mitochondrial activity and limited regenerative capacity [141]. Notably, EGCG exerts its cardioprotective and anti-cancer effects largely through modulation of ROS generation and scavenging, thereby restoring redox balance and preventing oxidative injury [135,136,137,138,139,140,141].

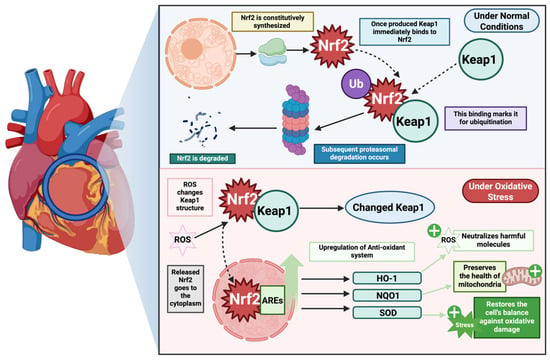

To maintain redox homeostasis, cells have evolved complex defense mechanisms against oxidative stress, among which the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway plays a critical role [140,142,143]. Nrf2 (nuclear factor 2 related to erythroid factor 2), a transcription factor, acts as a major sensor for oxidative and electrophilic stresses [140,141], while Keap1 (Kelch-like ECH-associated protein-1) protein regulates the function of Nrf-2 [140,142]. Under basal conditions, Nrf2 is sequestered into the cytoplasm by Keap1, which facilitates its ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation [140,142,143]. Hence, under unstressed conditions, Nrf2 is synthesized but constantly degraded, maintaining only a low level [143]. However, under oxidative stress, the cysteine residues in Keap1 become oxidized, leading to conformational changes in Keap1. As a result, Nrf2 dissociates from the complex, stabilizes, and translocates to the nucleus [139,140,142,143]. In the nucleus, it binds to antioxidant response elements (ARE) and upregulates the expression of antioxidant enzyme, such as heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), NADPH quinone oxidoreductase-1 (NQO1), glutamate–cysteine ligase catalytic and modifier subunits (GCLC, GCLM), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), glutathione S-transferase, superoxide dismutase (SOD), and others. [139,142,143]. Collectively, these enzymes detoxify ROS, replenish glutathione stores, and preserve mitochondrial integrity [144,145]. Figure 3 illustrates the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway, highlighting Nrf2’s key role in the antioxidant system.

Figure 3.

Keap1-Nrf2 axis mediated antioxidant activity. The figure highlights the keap-1-Nrf2 pathway, with a key highlight on Nrf2’s activity in the antioxidant defense. Nrf2 is constitutively synthesized and, under basal conditions, targeted for proteasomal degradation via Keap1. However, under normal conditions when there is no ROS-mediated stressor, Keap1 protein binds to Nrf2 preventing it from conducting the downstream signaling axis. However, in the presence of ROS-mediated stress, Keap1 changes its molecular structure, allowing Nrf2 to act as a transcription factor and upregulate the transcription of key antioxidant defense enzymes—HO-1, NQO1, SOD—allowing them to neutralize the ROS, preserve mitochondrial health, and restore balance. This system is dysregulated in heart failure, allowing ROS-mediated stress to condition, damaging the cell, leading to adverse cardiogenic outcomes.

Clinical and experimental studies have provided considerable evidence that during heart failure, there is increased oxidative stress in the myocardium and at a systemic level [146,147]. This oxidative stress is a pivotal driver in the pathogenesis and progression of heart failure, with ROS levels acting as possible markers of disease severity [148]. The major cause for increased ROS is mitochondrial dysfunction which is caused by disorganization in substrate metabolism and shift of energy production from mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation to glycolytic pathways leading to intracellular lipid accumulation [149,150]. As a result, there is impaired oxidative phosphorylation, abnormal mitochondrial dynamics, and mitochondrial DNA damage [148,151]. Specifically, ETC complexes I and III are defective leading to decreased ATP production, increased electron loss, and hence excessive ROS production [148]. Chronic increases in ROS lead to a disastrous cycle of mitochondrial DNA damage and functional decline, causing further ROS generation and cellular injury [151,152]. Moreover, ROS directly attenuates contractile function by modifying excitation-contraction coupling proteins, activating hypertrophy signaling kinases, mediating apoptosis, and causing extracellular matrix remodeling [148,152]. These cellular events drive myocardial remodeling, fibrosis, and failure [148,150,152].

Despite being a protective system, the Keap1-Nrf2 axis is often compromised in heart failure [143,153,154]. In murine models of transverse aortic constriction (TAC)-induced pressure overload, Nrf2 initially rises transiently during the adaptive hypertrophy phase but declines as maladaptive remodeling develops, eventually causing chronic heart failure [155]. Mice with a knockout of Nrf2 (Nrf2−/−) show exaggerated pathological hypertrophy, fibrosis, and apoptosis, and accelerated transition to heart failure, whereas overexpression of Nrf2 suppresses ROS and protects cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts from stress-induced growth [155]. Similar findings are observed in ischemic injury models. Following induction of myocardial infarction, Nrf2−/− mice exhibit maladaptive remodeling, left ventricular dilation, reduced cardiac output, and a rapid progression to heart failure, with mortality rates nearly doubled compared to wild-type controls [153].

Conversely, knockout of cardiomyocyte specific Keap1 and activation of Nrf2 in mice with suprarenal abdominal aortic constriction confers protection against pressure overload-induced fibrosis, cell death, and contractile dysfunction, while still maintaining antioxidant gene expression [156]. These models together underscore Nrf2’s essential role in protecting against oxidative stress-induced remodeling post-injury.

Importantly, human data align with these experimental observations. On transcriptomic analysis of patients with dilated or ischemic cardiomyopathy, the Nrf2/Keap1 ratio was revealed to be elevated, suggesting a compensatory activation; however, the expression of key antioxidant and detoxification genes was consistently reduced [154]. This discrepancy between Nrf2 activation and transcriptional efficacy highlights a functional impairment of the pathway in human heart failure. Thus, impaired Keap1–Nrf2 signaling not only reduces antioxidant defenses, but also promotes a vicious circle of oxidative damage, fibrosis, and cardiac dysfunction.

Given its central role, enhancing Nrf2 activity has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy. As such, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), the most abundant catechin in green tea, has attracted attention for its potent antioxidant and cardioprotective properties [22,157]. Due to its polyphenolic hydroxyl groups, EGCG possesses direct antioxidant activity [157,158,159], enabling free radical scavenging to produce more stable phenolic radicals, inhibition of lipid peroxidation, and enhancement of endogenous antioxidant enzyme activity [160].

More importantly, EGCG indirectly boosts antioxidant capacity by modulating the Keap–Nrf2 axis through powerful activation of Nrf2 [157,161,162,163]. Mechanistically, EGCG is speculated to interact with cysteine residues on Keap1, leading to conformational changes that prevent Keap1 from degrading Nrf2 [163]. This facilitates Nrf2 stabilization, nuclear translocation, and transcription of ARE genes [143]

In murine models of coronary heart disease, addition of EGCG activates the Nrf2/HO-1/NQO1 pathway restoring protein expression of Nrf2, HO-1, and NQO1, thereby reducing cardiac tissue damage [162]. Similarly, EGCG enhances activation of Keap1/P62/Nrf2 signaling pathway in mice models with intracranial hemorrhage, inhibiting inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis [157]. Moreover, in diabetic nephropathy models, EGCG’s cardioprotective effects were abolished in Nrf2 knockout mice, highlighting that its protective actions are Nrf2-dependent [163].

These molecular effects translate into significant cardiovascular benefits. EGCG reduces overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, and apoptosis, while decreasing risk of ischemia-reperfusion injury [22]. It also improves endothelial function, arterial compliance, and blood pressure regulation [158]. Clinical studies further show that regular consumption of green tea extract lowers LDL cholesterol, improves serum antioxidant capacity, and reduces inflammatory markers in individuals with cardiovascular risk factors [20]. These data establish EGCG not only as a direct antioxidant but also as a potent Nrf2 activator with a promising future as an adjunct in the management of cardiovascular disease and heart failure.

While EGCG has been shown to activate Nrf2 and restore antioxidant capacity across diverse preclinical models, the mechanistic fidelity of this interaction remains incompletely defined. Current evidence is largely inferential, relying on surrogate readouts of downstream ARE-driven gene expression rather than direct structural or biophysical demonstration of EGCG–Keap1 cysteine adduct formation. Moreover, although compensatory dysregulation of Nrf2 target gene transcription in human cardiomyopathy highlights a translational paradox, Nrf2 stabilization does not always equate to functional antioxidant reprogramming. Future work must therefore delineate the kinetics and stoichiometry of EGCG–Keap1 interactions using covalent adductomics, mass spectrometry, and crystallography, and integrate these with redox flux analyses in human cardiomyocytes. Equally critical will be the deployment of clinically relevant, bioavailable formulations in large-animal HF models with longitudinal redox imaging, to establish whether Nrf2 activation by EGCG translates into durable attenuation of oxidative injury in vivo.

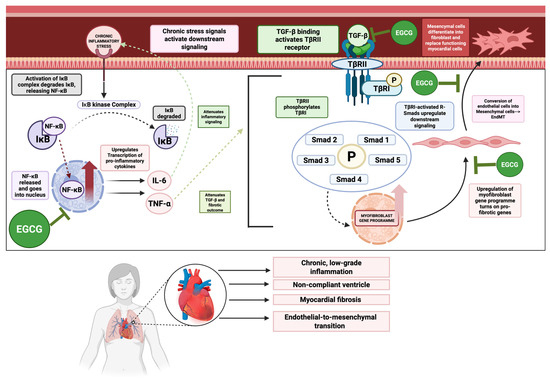

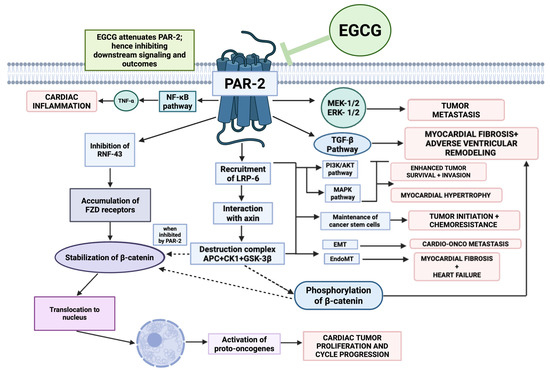

10.2. Inflammation and Fibrosis

Chronic, low-grade inflammation, often mediated by the NF-κB signaling pathway, contributes significantly to myocardial remodeling and dysfunction in HF (illustrated in Figure 4) [164,165]. This is compounded by progressive myocardial fibrosis, a process largely driven by the TGF-β/Smad signaling axis, which leads to excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition and a stiffened, non-compliant ventricle [166,167,168].

Figure 4.

NF-κB, TGF-β, EndoMT mediated inflammation and cardiogenic fibrosis in heart failure. This figure illustrates key mechanisms involved in inflammatory and fibrosis-driven heart failure. NF-κb promotes chronic, low-grade inflammation and its synthesis of TNF-α synergizes with the TGF-β signaling axis to upregulate this axis and its fibrotic outcomes. TGF-β causes downstream signaling and phosphorylation of R-smads, which act as transcription factors to upregulate the myofibroblast gene program. One outcome of this gene program is endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndoMT), in which endothelial factors are switched off, while mesenchymal factors are turned on, allowing these endothelial cells to transform into mesenchymal cells and further mature into fibroblasts that lay down collagen and displace functioning myocytes, thus worsening the fibrogenesis, inflammation, and function in heart failure. However, EGCG can inhibit NF-κB, TGF-β, EndoMT signaling axes, thus attenuating these adverse outcomes in heart failure.

EGCG exerts potent anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting NF-κB activation, thereby suppressing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL)-6 [159,169,170]. Simultaneously, EGCG modulates the TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling pathway, reducing myocardial fibrosis and ventricular collagen remodeling in mouse models of heart failure [171]. It also effectively inhibits endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT), a process where endothelial cells acquire a fibrotic phenotype, which is a key contributor to cardiac fibrosis [172,173].

The preclinical evidence for EGCG’s anti-fibrotic action is robust, targeting both the core signaling pathways and the cellular origin of fibroblasts. However, the lack of human studies evaluating the long-term impact of EGCG on endpoints like left ventricular remodeling and fibrosis, as measured by non-invasive imaging techniques such as cardiac MRI, remains a major translational barrier.

To overcome this translational gap, future work must progress beyond descriptive preclinical models towards precision interrogation of inflammatory–fibrotic circuits. CRISPR/Cas9-based strategies offer a particularly powerful avenue, targeted editing of NF-κB or TGF-β/Smad pathway nodes in human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes and fibroblasts could definitively establish causal links between EGCG exposure and transcriptional reprogramming. In parallel, CRISPR-mediated fluorescent tagging of Smad3 or NF-κB subunits would permit live-cell tracking of nuclear translocation dynamics under EGCG treatment, providing mechanistic resolution at single-cell level. Equally, genome-wide CRISPR knockout or CRISPRa/i screens could identify previously unrecognized co-factors or enhancers that condition EGCG’s anti-fibrotic efficacy, enabling rational combination strategies. Coupling such molecular precision with non-invasive endpoints such as longitudinal cardiac MRI for fibrosis quantification, and plasma exRNA profiling of fibroblast activation, would yield an integrated translational pipeline, positioning EGCG not merely as a nutraceutical but as a tractable molecular probe for dissecting and modulating inflammatory–fibrotic remodeling in human HF.

10.3. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Energy Metabolism

Heart is an extremely energy-demanding organ, with mitochondria consuming a massive amount of ATP to support continuous contraction. In heart failure, a pathological shift from efficient fatty acid oxidation to a less efficient glucose metabolism, coupled with mitochondrial dysfunction, creates a state of chronic energy starvation [174]. Key regulatory proteins, including AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α), govern energy homeostasis and mitochondrial biogenesis [175]. AMPK is expressed in various tissues in the human body, including skeletal muscle, liver, heart, brain, and vasculature. It is a central cellular energy sensor that is activated in states of hypoxia, ischemia, nutritional deprivation (e.g., anorexia and fasting), or exercise that trigger an increased AMP/ATP ratio intracellularly. The main mode of activation of AMPK is through phosphorylation of upstream kinases like LKB1 and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK). Once activated, AMPK shifts cellular metabolism toward energy-generating catabolic pathways (glucose uptake, glycolysis, fatty acid oxidation) while suppressing ATP-consuming anabolic processes (fatty acid synthesis, cholesterol synthesis, protein synthesis), thereby preserving energy homeostasis [176,177]. It also directly enhances the activity of PGC-1α, a transcriptional coactivator that serves as a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism. By partnering with transcription factors such as nuclear respiratory factors (NRF1/2) and estrogen-related receptors (ERRs), PGC-1α drives the expression of mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), which is required for mitochondrial DNA replication and electron transport chain function. Through this network, it increases mitochondrial number and efficiency, promotes fatty acid oxidation, and maintains metabolic flexibility in the heart. In heart failure, PGC-1α expression is reduced, leading to impaired mitochondrial function and energy deficiency [175,178].

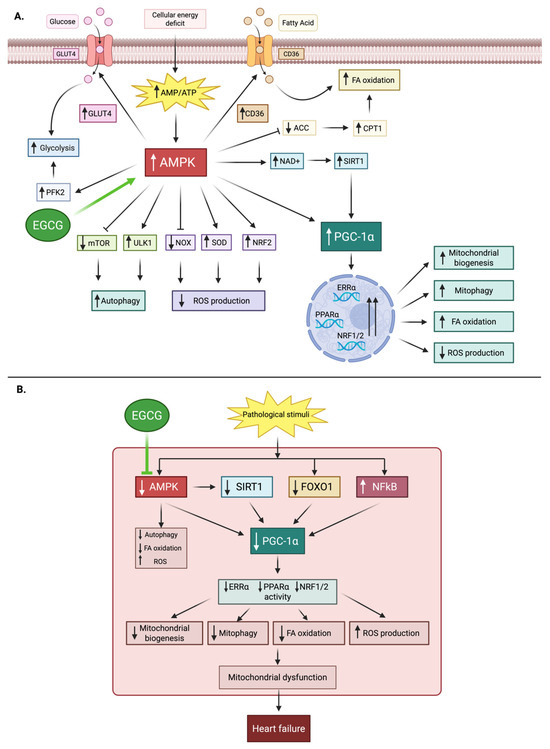

EGCG has been shown to enhance cardiac energy metabolism in pressure overload-induced cardiac dysfunction models [179]. It achieves this by activating the AMPK-PGC-1α axis, which leads to improved fatty acid oxidation, enhanced oxidative phosphorylation, and overall ATP preservation [180,181]. Figure 5 highlights the role of AMPK-PGC-1α in signaling in cardiac energy metabolism and the modulatory effects of EGCG under physiological and pathological conditions. Preclinical studies also demonstrate that EGCG promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and protects against mitochondrial damage in animal models of myocardial injury [182]. The metabolic effects of EGCG are a particularly compelling rationale for its use in HF; however, the data linking EGCG to these specific pathways in human myocardium is non-existent. A crucial next step is to conduct human trials with metabolic endpoints, such as cardiac PET or MRI, to confirm these findings in a clinical setting.

Figure 5.

Role of AMPK–PGC-1α signaling in cardiac energy metabolism and the modulatory effects of EGCG under physiological and pathological conditions. (A) Physiological conditions: Cellular energy deficit increases AMP/ATP ratio, activating AMPK. This promotes glucose uptake (GLUT4), glycolysis (PFK2), fatty acid (FA) oxidation (via CPT1), autophagy (ULK1, mTOR), antioxidant defense (NRF2, SOD, NOX), and stimulates PGC-1α through SIRT1. PGC-1α enhances mitochondrial biogenesis, mitophagy, FA oxidation, and reduces reactive oxygen species (ROS). EGCG further activates AMPK. (B) Pathological conditions: Reduced AMPK activity decreases SIRT1 and PGC-1α signaling, while FOXO1 and NF-κB are dysregulated. This impairs mitochondrial biogenesis, autophagy, FA oxidation, and increases ROS, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and heart failure. EGCG mitigates these changes by supporting AMPK activation. Abbreviations for Figure 5: AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; AMP/ATP, adenosine monophosphate/adenosine triphosphate; EGCG, epigallocatechin gallate; GLUT4, glucose transporter 4; PFK2, phosphofructokinase-2; CD36, cluster of differentiation 36; ACC, acetyl-CoA carboxylase; CPT1, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1; NAD+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; SIRT1, sirtuin 1; PGC-1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α; PPARα, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha; ERRα, estrogen-related receptor alpha; NRF1/2, nuclear respiratory factors 1/2; NRF2, nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2; SOD, superoxide dismutase; NOX, NADPH oxidase; ULK1, unc-51-like autophagy activating kinase 1; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; FOXO1, forkhead box O1; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; ROS, reactive oxygen species; FA, fatty acid.

Moreover, to advance beyond preclinical inference, future investigations must deploy cutting-edge mitochondrial phenotyping platforms capable of capturing EGCG’s metabolic effects with cellular and temporal precision. High-resolution respirometry (Seahorse XF and Oroboros O2k systems) coupled with stable isotope-resolved metabolomics (13C/15N tracers) can delineate flux through fatty acid β-oxidation, glycolysis, and the TCA cycle under EGCG exposure. Super-resolution live-cell imaging modalities such as STED and lattice light-sheet microscopy, combined with mitochondrial membrane potential probes and Ca2+ indicators, would permit dynamic visualization of cristae remodeling, fission–fusion kinetics, and organelle-ER crosstalk. Cryo-electron tomography could further resolve ultrastructural alterations in respiratory supercomplexes, while multiplexed immunogold EM would map AMPK–PGC-1α signaling hubs spatially. Integration of these high-content datasets with AI-driven multimodal analytics, graph neural networks trained on imaging, metabolomic, and transcriptomic inputs could yield predictive models of mitochondrial resilience to energetic stress. Ultimately, translation will require validation in human myocardium, leveraging iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes stratified by metabolic genotype, and metabolic imaging endpoints (cardiac PET tracers for fatty acid and glucose uptake, hyperpolarized MRI for real-time fluxes). Such a precision, system-level approach would establish whether EGCG’s mitochondrial effects can be harnessed as a clinically actionable strategy in heart failure.

10.4. Apoptosis and Autophagy

The irreversible loss of cardiomyocytes due to apoptosis (programmed cell death) is a hallmark of heart failure, leading to a diminished contractile reserve [183]. Autophagy, a cellular recycling process, is dysregulated in HF; while it can be protective in clearing damaged cellular components, its excessive or maladaptive activation can also lead to cell death [184,185]. EGCG demonstrates a dual regulatory role in these processes. It acts as an anti-apoptotic agent, inhibiting pro-apoptotic caspases and regulating the balance of Bcl-2 and Bax proteins. In rat models of pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy, EGCG was shown to inhibit cardiomyocyte apoptosis and oxidative stress, highlighting its cardioprotective potential [186]. Moreover, in a rat model of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury, EGCG significantly reduced infarct size and cardiomyocyte apoptosis [187]. Mechanistically, EGCG also modulates autophagy often promoting a protective form of the process to clear damaged mitochondria and cellular debris, thereby improving cell survival [188]. However, the precise regulation of autophagy by EGCG is context-dependent and requires further clarification, particularly in a cardiac setting. More granular studies are needed to differentiate between EGCG’s pro-survival and pro-death effects, especially in different stages of HF.

In line, future studies dissecting EGCG’s dual regulation of apoptosis and autophagy must move beyond rodent hypertrophy and I/R models toward HF-associated CVD contexts with higher translational fidelity, such as diabetic cardiomyopathy, hypertensive heart disease, and chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity, each of which embodies oxidative, inflammatory, and metabolic perturbations described in earlier sections. Advanced single-cell multi-omics (scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq, and spatial transcriptomics) applied to failing myocardium could clarify whether EGCG biases autophagy toward a protective, mitophagy-dominant phenotype versus maladaptive self-digestion, and whether this shift is context-specific across disease substrates. High-content imaging platforms, including correlative light–electron microscopy and live-cell FRET biosensors for Bcl-2/Bax dynamics, could directly quantify apoptotic–autophagic crosstalk in real time. Integrating these datasets with artificial intelligence-driven trajectory-inference models, such as pseudotime or graph-learning algorithms, would enable reconstruction of dynamic state transitions across mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and fibrosis signatures would establish system-level maps of how EGCG orchestrates survival pathways in cardiomyocytes. Finally, CRISPR-based reporters engineered into iPSC-derived human cardiomyocytes could allow longitudinal tracking of caspase activation and autophagy flux under EGCG, benchmarked against disease-relevant stressors such as hyperglycaemia, pressure overload, or doxorubicin exposure. Such an integrated, disease-stratified pipeline would resolve whether EGCG’s context-dependent effects can be harnessed as a targeted survival modulator in heart failure and its comorbid cardiovascular syndromes.

11. EGCG in Myocardial Infarction and Ischemia Reperfusion

A large body of preclinical data from rodent and isolated heart models support EGCG’s protective role in myocardial infarction (MI) and ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury [159]. Studies show that EGCG pre-treatment or co-administration can significantly reduce myocardial infarct size, improve left ventricular (LV) developed pressure, and enhance the recovery of LV function [189]. These cardioprotective effects are primarily attributed to its potent antioxidant and anti-apoptotic properties. EGCG has been shown to improve hemodynamic recovery, increase tissue ATP levels, and reduce markers of oxidative and nitrosative stress in isolated perfused rabbit hearts subjected to cardioplegic arrest [190]. These findings present a strong rationale for evaluating EGCG as a potential adjunct therapy to modern reperfusion strategies like percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The goal would be to mitigate reperfusion injury, which paradoxically exacerbates myocardial damage after blood flow is restored. Despite the consistent and promising preclinical data, a substantial translational gap exists, with no dedicated human clinical trials evaluating EGCG’s efficacy in patients with acute MI or those undergoing reperfusion therapy. This represents a critical, unmet clinical need and an area of high-priority research.

Hence, a rational next step would be the design of an early phase, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial evaluating a bioavailable EGCG formulation as an adjunct to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with acute or elective MI. EGCG could be administered via sublingual or lipid-based nanoformulation loading prior to PCI, with continued dosing in the early post-reperfusion period, and outcomes assessed by cardiac MRI endpoints such as infarct size, myocardial salvage index, and microvascular obstruction, together with circulating biomarkers of oxidative/nitrosative stress. Importantly, a factorial design incorporating standard-of-care agents (e.g., high-intensity statins, β-blockers, ACE inhibitors/ARNIs, and P2Y12 inhibitors) would allow interrogation of synergistic or additive effects, particularly as statins and renin–angiotensin inhibitors converge mechanistically on redox and inflammatory pathways that EGCG also modulates. Risk-enriched subpopulations such as patients with metabolic comorbidities (type 2 diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome) or genetic predisposition to premature MI (e.g., familial hypercholesterolaemia, elevated Lp(a), PCSK9 variants) could be leveraged both as mechanistic models and as trial cohorts where EGCG’s pleiotropic actions may yield amplified benefit. An innovative yet feasible extension would be to integrate AI-enabled multimodal analytics, combining serial metabolic imaging (PET tracers for substrate utilization, hyperpolarized MRI for real-time flux) with plasma exRNA and proteomic signatures, to generate predictive response phenotypes. Such a trial would directly address the translational gap by testing EGCG not merely as a phytochemical antioxidant but as a system-level cardioprotective adjunct within contemporary reperfusion paradigms.

12. EGCG and Cardiac Arrhythmogenesis

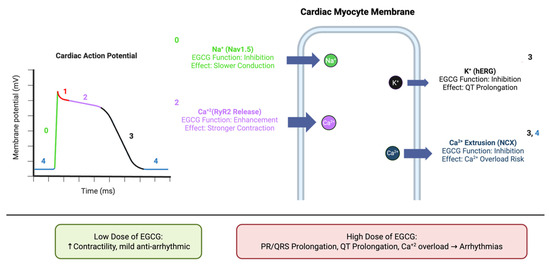

While less explored than its metabolic and anti-fibrotic effects, EGCG’s potential as an anti-arrhythmic agent is an emerging area of research. It has been shown to modulate the activity of key ion channels that regulate cardiac excitability. EGCG inhibits the cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5 in a dose-dependent manner, primarily by modulating channel inactivation [191]. It also interacts with potassium (K+) channels, with some studies showing inhibition of the human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG) K+ channel, a known target for pro-arrhythmic drugs [192].

EGCG’s effects on intracellular calcium (Ca2+) handling are particularly notable. At nanomolar concentrations, EGCG increases myocyte contractility by enhancing sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ loading and activating ryanodine receptor channels (RyR2). It also inhibits the sodium–calcium exchanger (NCX), which slows Ca2+ extrusion from the cell, further enhancing Ca2+ transients and contractility. These effects on Ca2+ handling are summarized in Figure 6, which illustrates EGCG’s modulation of Nav1.5, hERG, RyR2, and NCX during the cardiac action potential [193]. The effects of EGCG on cardiac electrophysiology appear to be dose-dependent and biphasic. While low concentrations may provide a positive inotropic effect and stabilize Ca2+ handling, high concentrations (as might be found in unregulated supplements) have been shown to prolong PR and QRS intervals and alter the ST-T wave segment, suggesting potential pro-arrhythmic effects [194]. This finding is critical and points to a narrow therapeutic window for EGCG as an anti-arrhythmic agent.

Figure 6.