Synthesis, Physicochemical Characterization, and Biocidal Evaluation of Three Novel Aminobenzoic Acid-Derived Schiff Bases Featuring Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

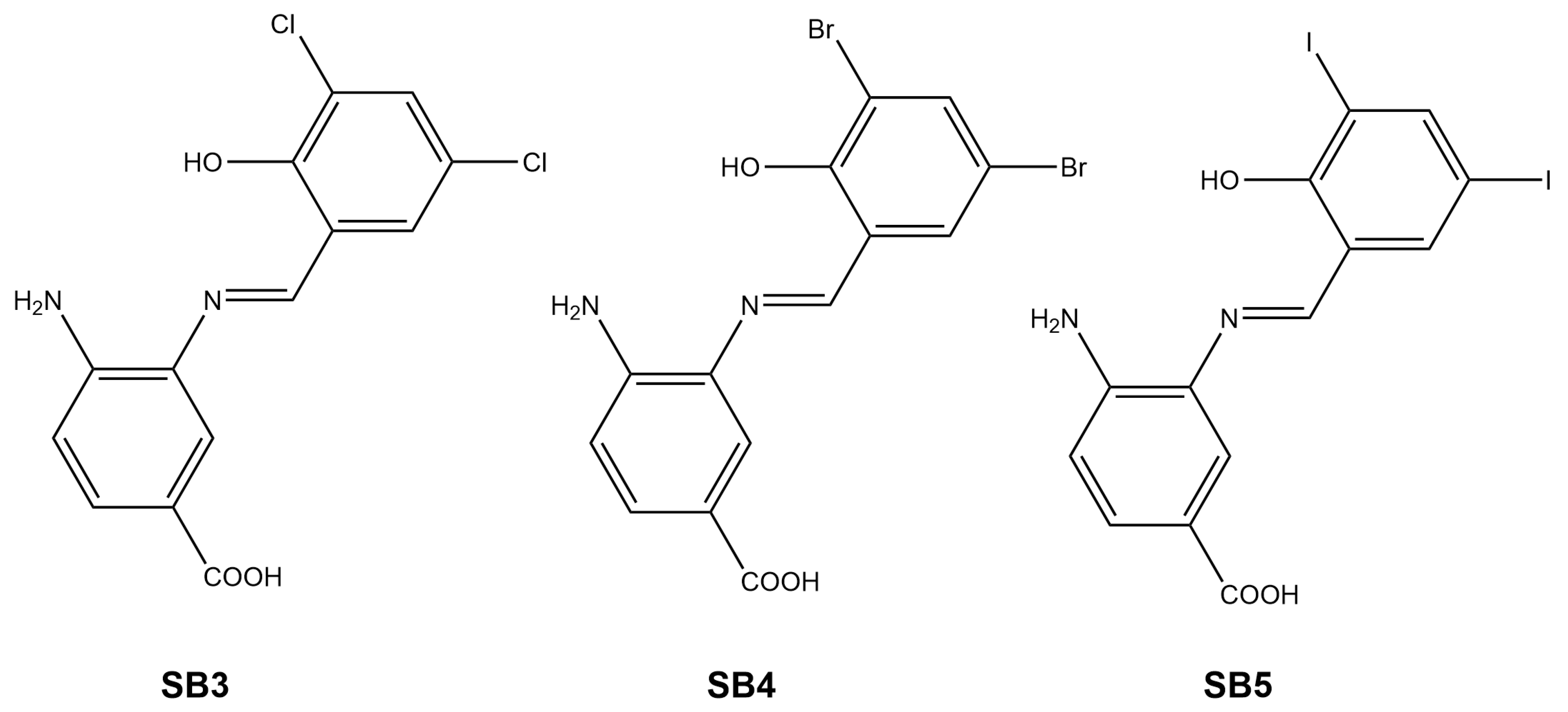

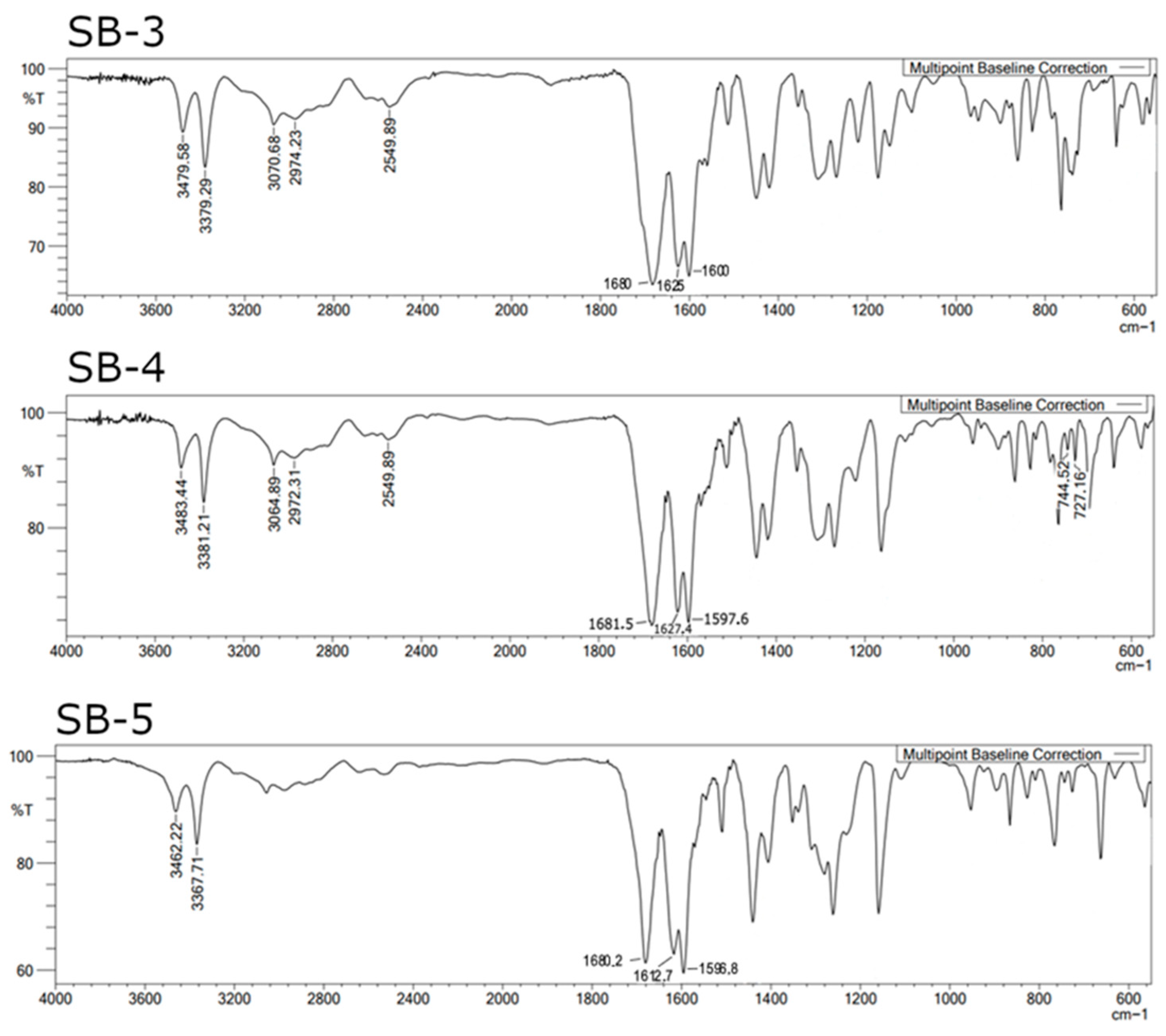

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Schiff Bases

2.2. UV-Vis Studies

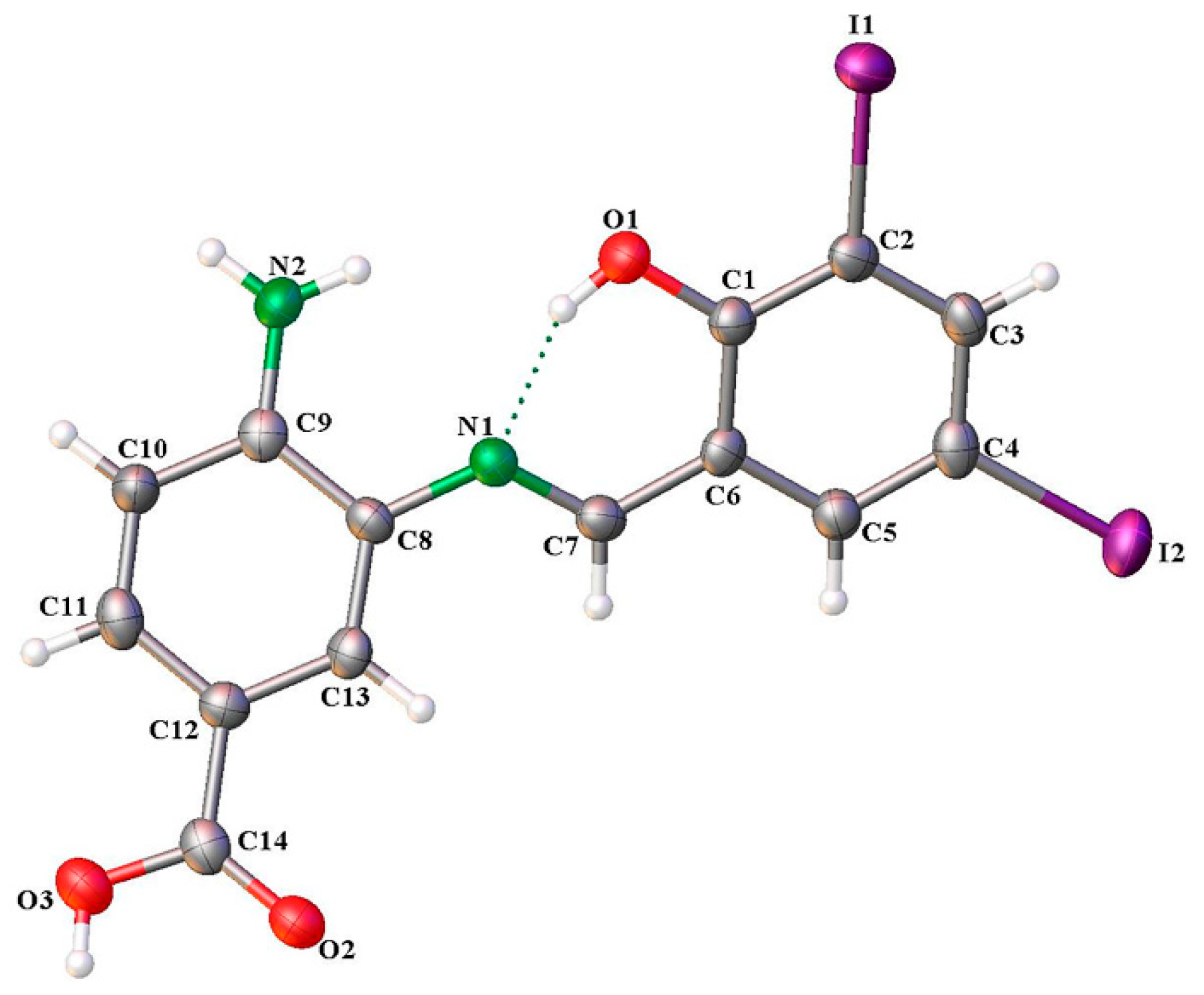

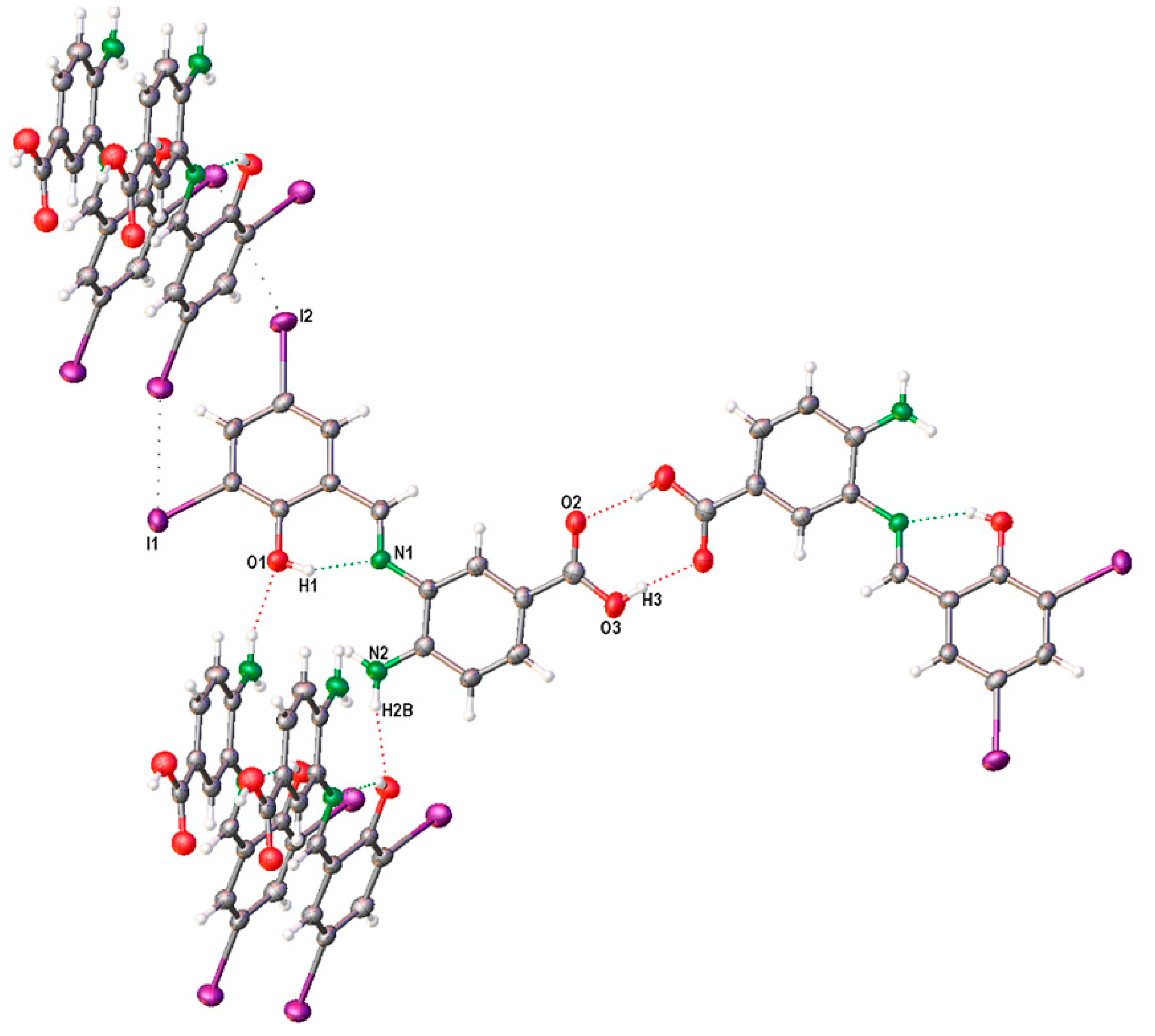

2.3. X-Ray Structure of SB-5

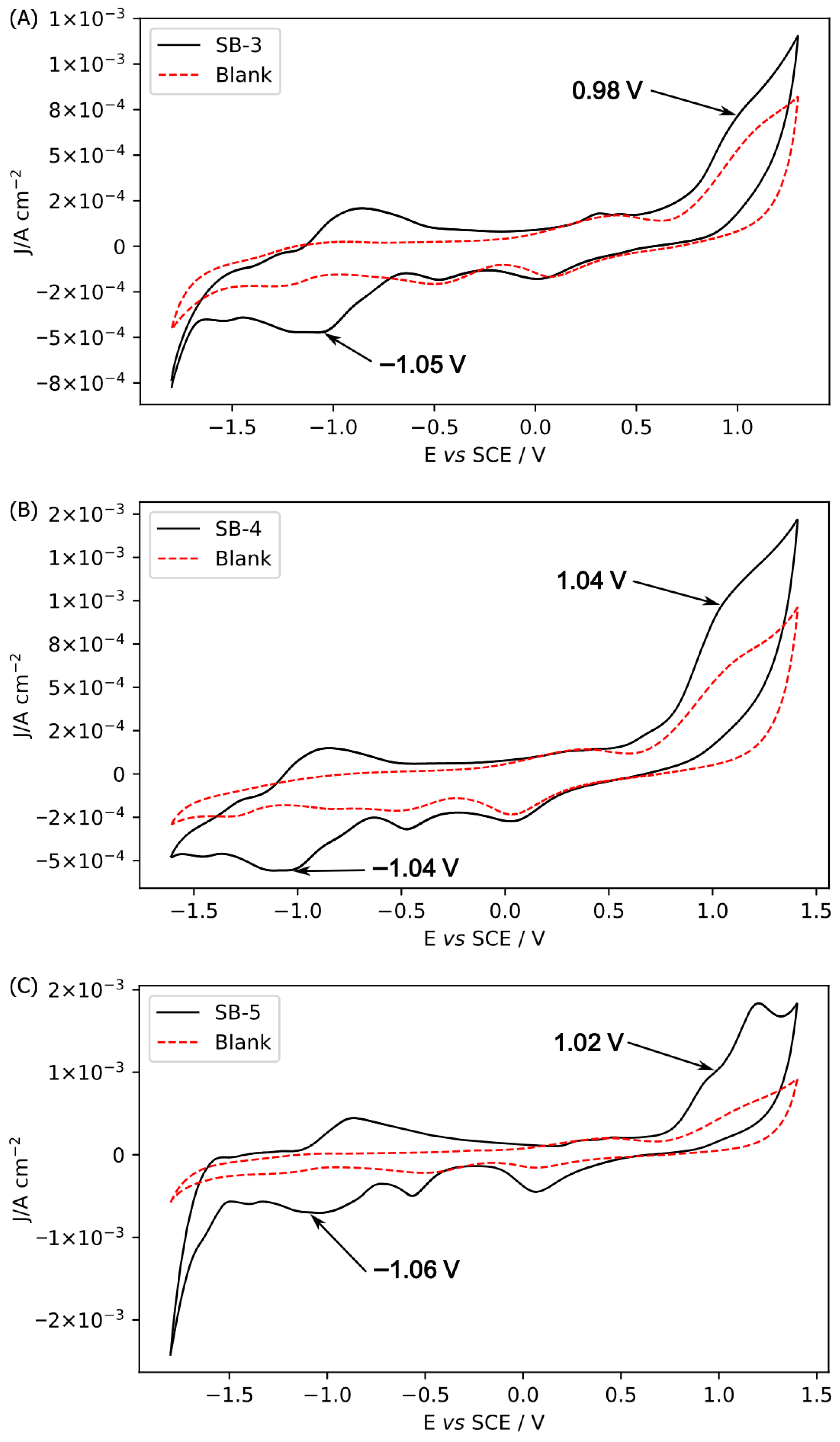

2.4. Electrochemical Behaviors

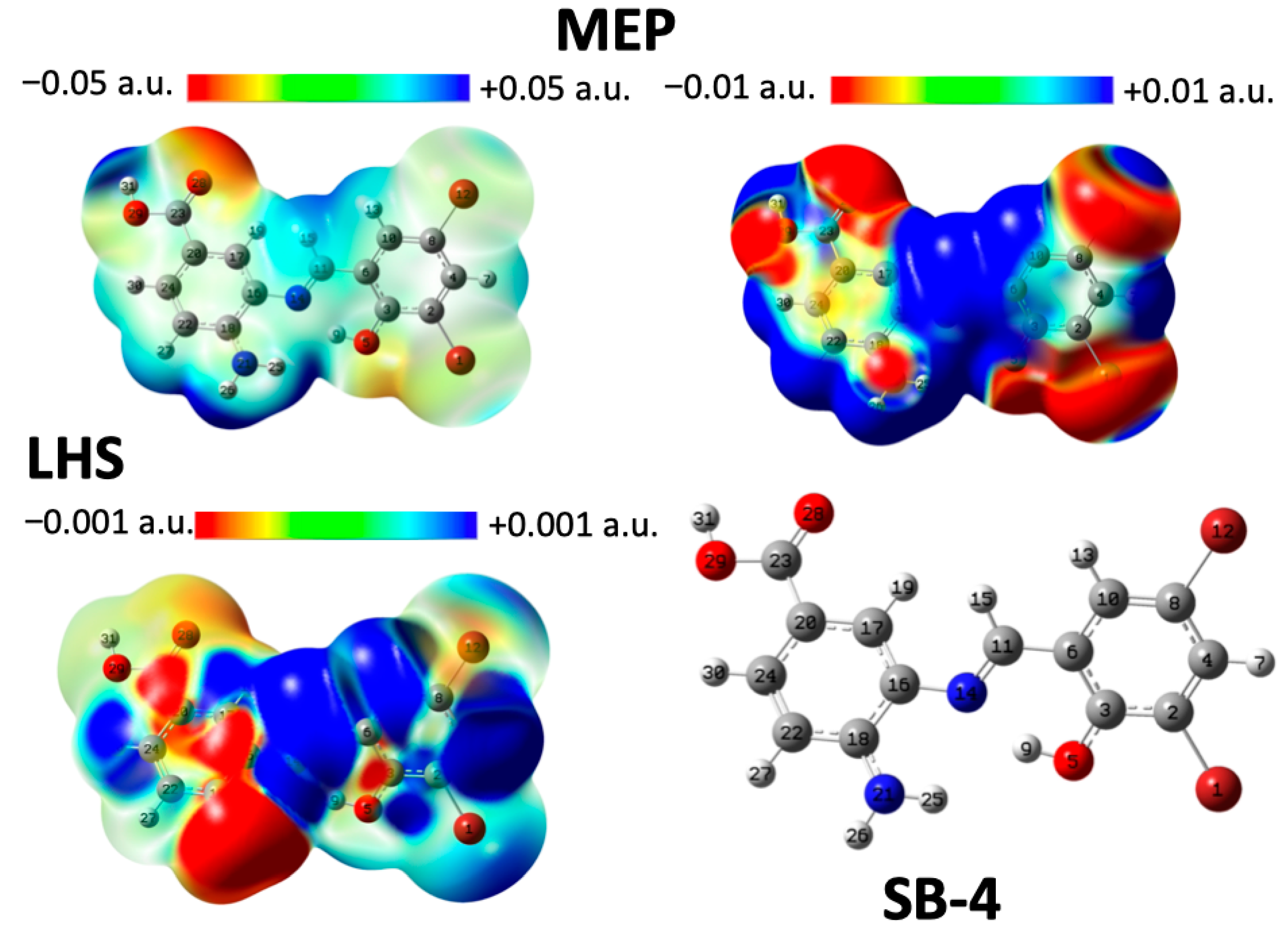

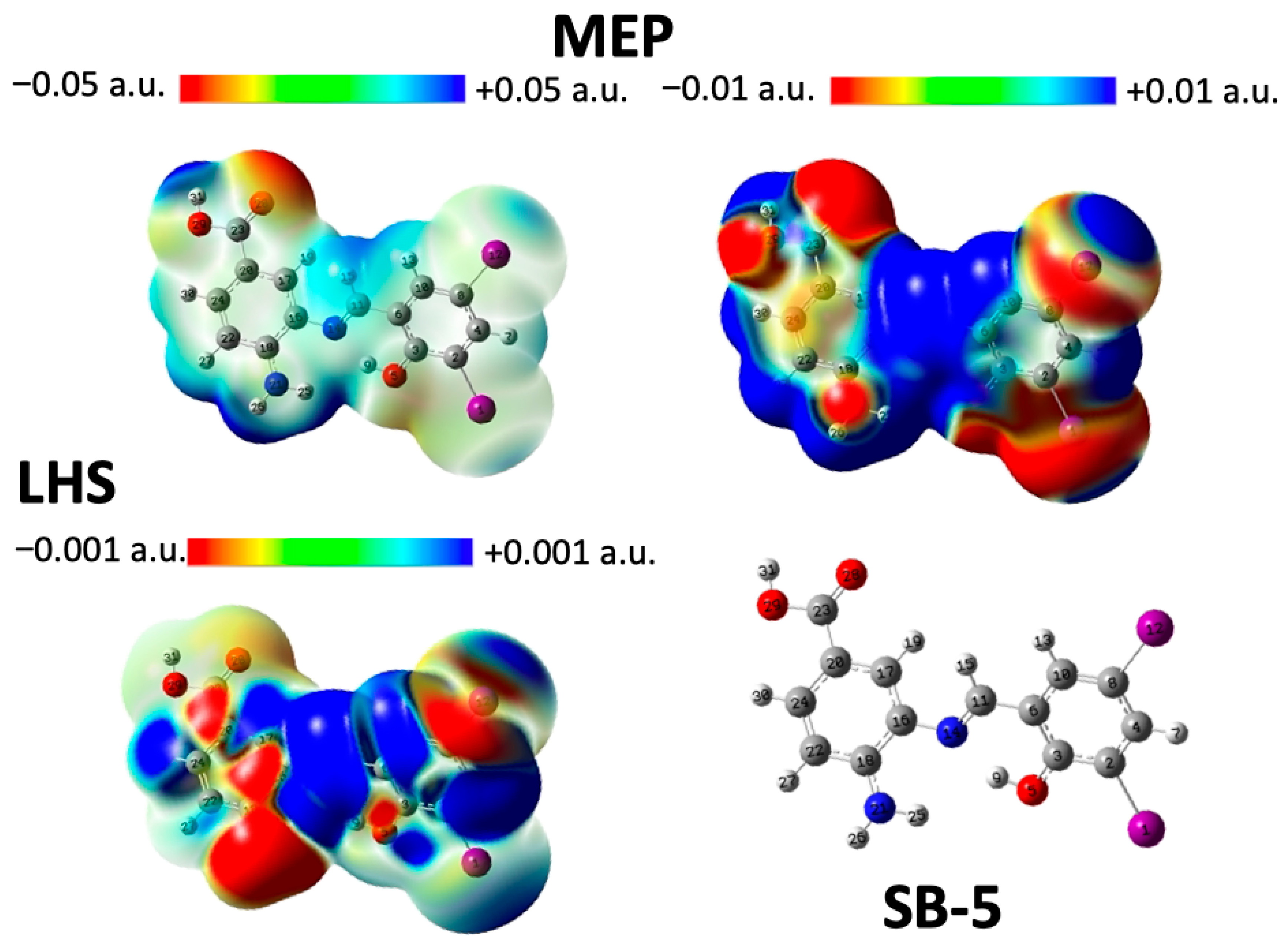

2.5. Analysis of Local Reactivity

2.6. Analysis of Antimicrobial Activity

2.7. HeLa Cell Viability Assays

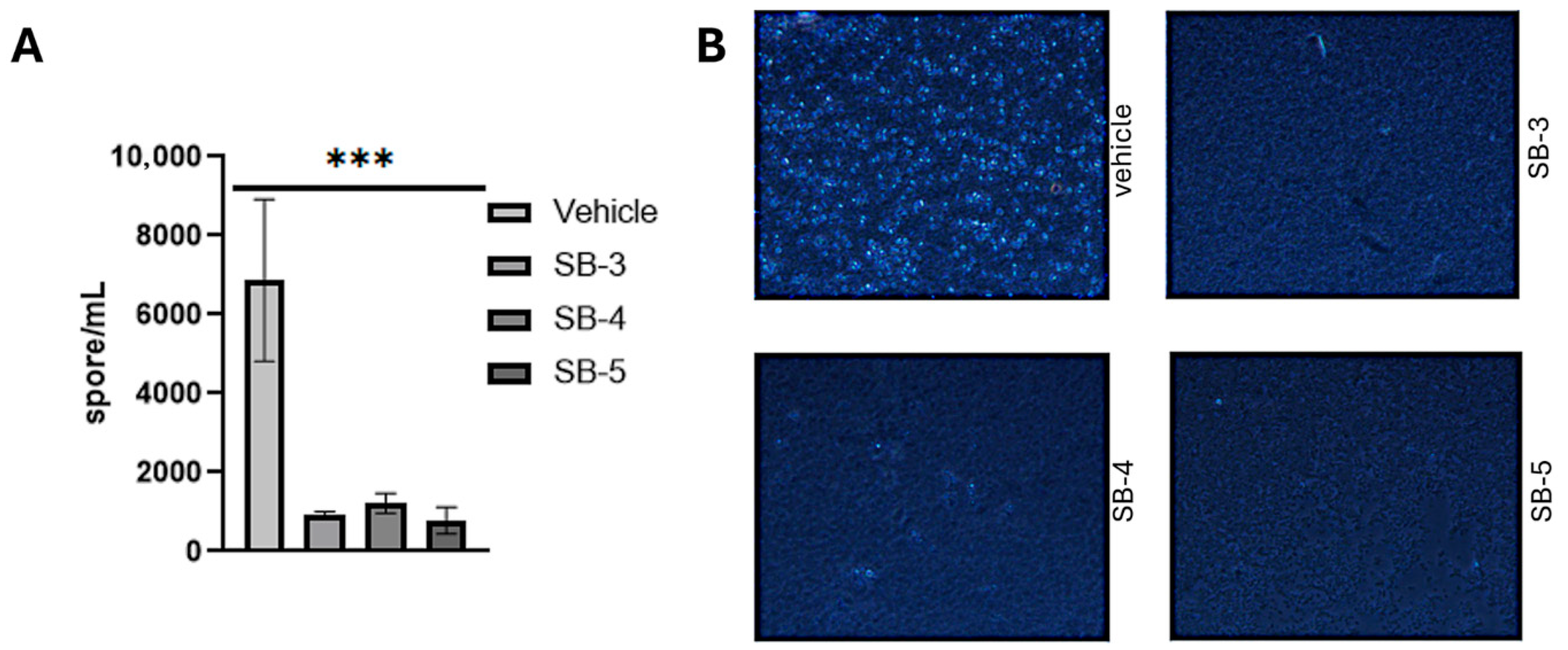

2.8. Cytotoxicity Assays Botrytis cinerea

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and Instruments

3.2. Procedure for Preparing SB-3, SB-4, and SB-5

3.2.1. Synthesis of (E)-4-Amino-3-((3,5-di-chloride-2-hydroxybenzylidene)amino) Benzoic Acid (SB-3)

3.2.2. Synthesis of (E)-4-Amino-3-((3,5-di-bromide-2-hydroxybenzylidene)amino) Benzoic Acid (SB-4)

3.2.3. Synthesis of (E)-4-Amino-3-((3,5-di-iodide-2-hydroxybenzylidene)amino) Benzoic Acid (SB-5)

3.3. Structure Determination

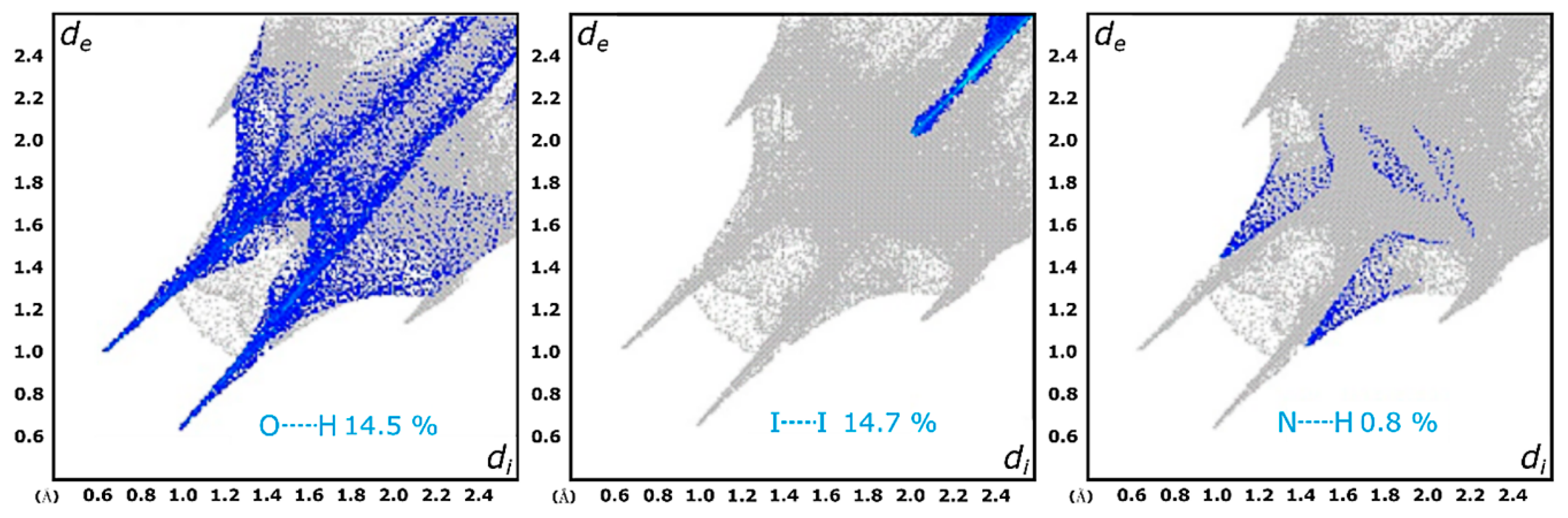

3.4. Hirshfeld Surface Analysis

3.5. Antimicrobial Activity

3.5.1. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) for Aerobic and/or Facultative Bacteria

3.5.2. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) for Anaerobic Bacteria

3.5.3. Sporulation Assay

3.5.4. MTT Assay

3.5.5. Botrytis cinerea Inhibition Assay

3.5.6. Statistical Analysis for Biological Assays

3.6. Computational Details

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boublia, A.; Lebouachera, S.E.I.; Haddaoui, N.; Guezzout, Z.; Ghriga, M.A.; Hasanzadeh, M.; Benguerba, Y.; Drouiche, N. State-of-the-art review on recent advances in polymer engineering: Modeling and optimization through response surface methodology approach. Polym. Bull. 2022, 80, 5999–6031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Noreen, S.; Asim, S.; Liaqat, Z.; Ibrahim, H.; Talib, R. A Comprehensive on Synthesis and Antimicrobial Evaluation of Substituted-Arylideneamino-5-(5-Chlorobenzofuran-2-yl)-1, 2, 4-Triazole-3-Thiol Derivatives/Schiff Bases. J. Fluoresc. 2025, 35, 3733–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gacitua, M.; Carreno, A.; Morales-Guevara, R.; Paez-Hernandez, D.; Martinez-Araya, J.I.; Araya, E.; Preite, M.; Otero, C.; Rivera-Zaldivar, M.M.; Silva, A.; et al. Physicochemical and Theoretical Characterization of a New Small Non-Metal Schiff Base with a Differential Antimicrobial Effect against Gram-Positive Bacteria. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulechfar, C.; Ferkous, H.; Delimi, A.; Djedouani, A.; Kahlouche, A.; Boublia, A.; Darwish, A.S.; Lemaoui, T.; Verma, R.; Benguerba, Y. Schiff bases and their metal Complexes: A review on the history, synthesis, and applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023, 150, 110451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, I.; Ahmad, M.; Saleem, M.; Ahmed, A. Pharmaceutical significance of Schiff bases: An overview. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, D.P.; Gautam, A.K.; Verma, A.; Gautam, Y. Schiff bases and their possible therapeutic applications: A review. Results Chem. 2025, 13, 101941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, C.; Nakane, D.; Akitsu, T. Recent Advances in Chiral Schiff Base Compounds in 2023. Molecules 2023, 28, 7990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, N.; Bingöl, M.; Buldurun, K.; Çolak, N. Synthesis, structure determination of Schiff bases and their PdII complexes and investigation of palladium catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1319, 139566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raczuk, E.; Dmochowska, B.; Samaszko-Fiertek, J.; Madaj, J. Different Schiff Bases-Structure, Importance and Classification. Molecules 2022, 27, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Yadav, P.; Kaur Sodhi, K.; Tomer, A.; Bali Mehta, S. Advancement in the synthesis of metal complexes with special emphasis on Schiff base ligands and their important biological aspects. Results Chem. 2024, 7, 101222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagar, S.; Raizada, S.; Tripathee, N. A review on various green methods for synthesis of Schiff base ligands and their metal complexes. Results Chem. 2023, 6, 101153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, W.H.; Deghadi, R.G.; Mohamed, G.G. Preparation, geometric structure, molecular docking thermal and spectroscopic characterization of novel Schiff base ligand and its metal chelates. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2016, 127, 2149–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfa Tefera, D. Synthesis, Characterization and Biological Activities of Schiff Bases and Their Transition Metal Complexes. World J. Appl. Chem. 2023, 3, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panghal, M.; Kumari, S.; Goel, N.; Rani, I. Synthesis, Spectroscopic Characterization, Antioxidant Properties and Antimicrobial Activity of Transition Metal Complexes from Novel Schiff Base. Curr. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2023, 42, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinova, P.E.; Tamahkyarova, K.D. Synthesis, Investigation, Biological Evaluation, and Application of Coordination Compounds with Schiff Base—A Review. Compounds 2025, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Song, Q.; Jin, Y.; Feng, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, K. Advances in Schiff Base and Its Coating on Metal Biomaterials—A Review. Metals 2023, 13, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreno, A.; Rodriguez, L.; Paez-Hernandez, D.; Martin-Trasanco, R.; Zuniga, C.; Oyarzun, D.P.; Gacitua, M.; Schott, E.; Arratia-Perez, R.; Fuentes, J.A. Two New Fluorinated Phenol Derivatives Pyridine Schiff Bases: Synthesis, Spectral, Theoretical Characterization, Inclusion in Epichlorohydrin-beta-Cyclodextrin Polymer, and Antifungal Effect. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreño, A.; Zúñiga, C.; Páez-Hernández, D.; Gacitúa, M.; Polanco, R.; Otero, C.; Arratia-Pérez, R.; Fuentes, J.A. Study of the structure–bioactivity relationship of three new pyridine Schiff bases: Synthesis, spectral characterization, DFT calculations and biological assays. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 8851–8863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreno, A.; Morales-Guevara, R.; Cepeda-Plaza, M.; Paez-Hernandez, D.; Preite, M.; Polanco, R.; Barrera, B.; Fuentes, I.; Marchant, P.; Fuentes, J.A. Synthesis, Physicochemical Characterization, and Antimicrobial Evaluation of Halogen-Substituted Non-Metal Pyridine Schiff Bases. Molecules 2024, 29, 4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coanda, M.; Limban, C.; Nuta, D.C. Small Schiff Base Molecules-A Possible Strategy to Combat Biofilm-Related Infections. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vhanale, B.T.; Deshmukh, N.J.; Shinde, A.T. Synthesis, characterization, spectroscopic studies and biological evaluation of Schiff bases derived from 1-hydroxy-2-acetonapthanone. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakara, C.T.; Patil, S.A.; Toragalmath, S.S.; Kinnal, S.M.; Badami, P.S. Synthesis, characterization and biological approach of metal chelates of some first row transition metal ions with halogenated bidentate coumarin Schiff bases containing N and O donor atoms. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2016, 157, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jezierska, A.; Tolstoy, P.M.; Panek, J.J.; Filarowski, A. Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonds in Selected Aromatic Compounds: Recent Developments. Catalysts 2019, 9, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidir, I.; Gulseven Sidir, Y.; Gobi, S.; Berber, H.; Fausto, R. Structural Relevance of Intramolecular H-Bonding in Ortho-Hydroxyaryl Schiff Bases: The Case of 3-(5-bromo-2-hydroxybenzylideneamino) Phenol. Molecules 2021, 26, 2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhawarri, M.B.; Al-Thiabat, M.G.; Dubey, A.; Tufail, A.; Fouad, D.; Alrimawi, B.H.; Dayoob, M. ADME profiling, molecular docking, DFT, and MEP analysis reveal cissamaline, cissamanine, and cissamdine from Cissampelos capensis L.f. as potential anti-Alzheimer’s agents. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 9878–9891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, H.; Sun, H.; Zhao, X. Application of Density Functional Theory to Molecular Engineering of Pharmaceutical Formulations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masnabadi, N.; Thalji, M.R.; Alhasan, H.S.; Mahmoodi, Z.; Soldatov, A.V.; Ali, G.A.M. Structural, Electronic, Reactivity, and Conformational Features of 2,5,5-Trimethyl-1,3,2-diheterophosphinane-2-sulfide, and Its Derivatives: DFT, MEP, and NBO Calculations. Molecules 2022, 27, 4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchis, J.; Jaen-Gil, A.; Gago-Ferrero, P.; Munthali, E.; Farre, M.J. Characterization of organic matter by HRMS in surface waters: Effects of chlorination on molecular fingerprints and correlation with DBP formation potential. Water Res. 2020, 176, 115743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.; Tan, J.; Tang, C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, P.; Liu, D.; Peng, X. Chlorine isotope analysis of polychlorinated organic pollutants using gas chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry and evaluation of isotope ratio calculation schemes by experiment and numerical simulation. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1651, 462311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, W.F.; Price, D. Mass Spectrometry—Finding the Molecular Ion and What It Can Tell You: An Undergraduate Organic Laboratory Experiment. Chem. Educ. 2002, 7, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Low, B.; Shen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Hidalgo Delgado, D.; Chau, K.N.M.; Pang, Z.; Li, X.; Xia, J.; Li, X.F.; et al. Exposome-Scale Investigation of Cl-/Br-Containing Chemicals Using High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry, Multistage Machine Learning, and Cloud Computing. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 11099–11109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Chang, Q.; Dan, C.; Guo, W.; Wang, Y. Selective Identification of Organic Iodine Compounds Using Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 1275–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeu, M.C.; Freire, P.T.C.; Ayala, A.P.; Barreto, A.C.H.; Oliveira, L.S.; Bandeira, P.N.; dos Santos, H.S.; Teixeira, A.M.R.; Vasconcelos, D.L.M. Synthesis, crystal structure, ATR-FTIR, FT-Raman and UV spectra, structural and spectroscopic analysis of (3E)-4-[4-(dimethylamine)phenyl]but-3-en-2-one. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1264, 133222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suydam, F.H. The C=N Stretching Frequency in Azomethines. Anal. Chem. 2002, 35, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekoei, A.R.; Vatanparast, M. An intramolecular hydrogen bond study in some Schiff bases of fulvene: A challenge between the RAHB concept and the σ-skeleton influence. New J. Chem. 2014, 38, 5886–5891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filarowski, A. Intramolecular hydrogen bonding in o-hydroxyaryl Schiff bases. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2005, 18, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziembowska, T.; Majewski, E.; Rozwadowski, Z.; Brzezinski, B. Intramolecular hydrogen bonds in N-oxides of Schiff bases. J. Mol. Struct. 1997, 403, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, P.E. A Spectroscopic Overview of Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonds of NH…O,S,N Type. Molecules 2021, 26, 2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.A.; Lowe, G. Downfield displacement of the NMR signal of water in deuterated dimethylsulfoxide by the addition of deuterated trifluoroacetic acid. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 3225–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, Y.M.; Hassib, H.B.; Abdelaal, H.E. 1H NMR, 13C NMR and mass spectral studies of some Schiff bases derived from 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2009, 74, 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vhanale, B.; Kadam, D.; Shinde, A. Synthesis, spectral studies, antioxidant and antibacterial evaluation of aromatic nitro and halogenated tetradentate Schiff bases. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordanetto, F.; Tyrchan, C.; Ulander, J. Intramolecular Hydrogen Bond Expectations in Medicinal Chemistry. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.Y.; Tsai, H.Y. Synthesis, X-ray structure, spectroscopic properties and DFT studies of a novel Schiff base. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 18706–18724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiner, S. Enhancement of Halogen Bond Strength by Intramolecular H-Bonds. J. Phys. Chem. A 2023, 127, 4695–4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kala, A.L.A.; Kumara, K.; Harohally, N.V.; Lokanath, N.K. Synthesis, characterization and hydrogen bonding attributes of halogen bonded O-hydroxy Schiff bases: Crystal structure, Hirshfeld surface analysis and DFT studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1202, 127238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, R.M.; Khedr, A.M.; Rizk, H.F. UV-vis, IR and (1)H NMR spectroscopic studies of some Schiff bases derivatives of 4-aminoantipyrine. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2005, 62, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.T.; Li, L.; Cao, C.; Liu, J. The effect of intramolecular hydrogen bond on the ultraviolet absorption of bi-aryl Schiff bases. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2020, 34, e4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, M.; Kılıç, Z.; Hökelek, T. Intramolecular hydrogen bonding and tautomerism in Schiff bases. Part I. Structure of 1,8-di[N-2-oxyphenyl-salicylidene]-3,6-dioxaoctane. J. Mol. Struct. 1998, 441, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreño, A.; Vega, A.; Zarate, X.; Schott, E.; Gacitúa, M.; Valenzuela, N.; Preite, M.; Manríquez, J.M.; Chávez, I. Synthesis, Characterization and Computational Studies of (E)-2-{[(2-Aminopyridin-3-Yl) Imino]-Methyl}-4,6-Di-Tert-Butylphenol. Quim. Nova 2014, 37, 584–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreno, A.; Ladeira, S.; Castel, A.; Vega, A.; Chavez, I. (E)-2-[(2-Amino-pyridin-3-yl)imino]-meth-yl-4,6-di-tert-butyl-phenol. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E Struct. Rep. Online 2012, 68, o2507–o2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Hu, H.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, Z.; He, J. Investigation of heavy atom effects and pH sensitivity on the photocatalytic cross-dehydrogenative coupling reaction of halogenated fluorescein dyes. Dye. Pigment. 2025, 232, 112437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastasi, F.; Campagna, S.; Ngo, T.H.; Dehaen, W.; Maes, W.; Kruk, M. Luminescence of meso-pyrimidinylcorroles: Relationship with substitution pattern and heavy atom effects. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2011, 10, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orpen, A.G.; Brammer, L.; Allen, F.H.; Watson, D.G.; Taylor, R. Typical interatomic distances: Organometallic compounds and coordination complexes of the d- and f -block metals. In International Tables for Crystallography; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 812–896. [Google Scholar]

- Gilli, P.; Bertolasi, V.; Ferretti, V.; Gilli, G. Evidence for Intramolecular N−H⊙⊙⊙ O Resonance-Assisted Hydrogen Bonding in β-Enaminones and Related Heterodienes. A Combined Crystal-Structural, IR and NMR Spectroscopic, and Quantum-Mechanical Investigation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 10405–10417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OmarAli, A.-A.B.; Ahmed, R.K.; Al-Karawi, A.J.M.; Marah, S.; Kansız, S.; Sert, Y.; Jaafar, M.I.; Dege, N.; Poyraz, E.B.; Ahmed, A.M.A.; et al. Designing of two new cadmium(II) complexes as bio-active materials: Synthesis, X-ray crystal structures, spectroscopic, DFT, and molecular docking studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1290, 135974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeşilbağ, S.; Kansız, S.; Dege, N.; Ağar, E. Structural Investigation and Hirshfeld Surface Analysis of Two [ONO]-Type Schiff Bases. J. Struct. Chem. 2024, 65, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansch, C.; Leo, A.; Taft, R.W. A survey of Hammett substituent constants and resonance and field parameters. Chem. Rev. 2002, 91, 165–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, D.; Nitschke, J.R. Designing multistep transformations using the Hammett equation: Imine exchange on a copper(I) template. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 9887–9892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrovs, R.; Drunka, L.; Auzins, A.A.; Jaudzems, K.; Salvalaglio, M. Polymorph-Selective Role of Hydrogen Bonding and π–π Stacking in p-Aminobenzoic Acid Solutions. Cryst. Growth Des. 2020, 21, 436–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermosilla-Ibanez, P.; Wrighton-Araneda, K.; Canon-Mancisidor, W.; Gutierrez-Cutino, M.; Paredes-Garcia, V.; Venegas-Yazigi, D. Substitution Effect on the Charge Transfer Processes in Organo-Imido Lindqvist-Polyoxomolybdate. Molecules 2018, 24, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loutfy, R.O.; Hsiao, C.K.; Ong, B.S.; Keoshkerian, B. Electrochemical evaluation of electron acceptor materials. Can. J. Chem. 1984, 62, 1877–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadpou, B.; Nematollahi, D.; Sharafi-Kolkeshvandi, M. Solvent effect on the electrochemical oxidation of N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-1,4-phenylenediamine. New insights into the correlation of electron transfer kinetics with dynamic solvent effects. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 253, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, A.; von Eschwege, K.G.; Conradie, J. Reduction potentials of para-substituted nitrobenzenes—An infrared, nuclear magnetic resonance, and density functional theory study. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2011, 25, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Araya, J.I. Why are the local hyper-softness and the local softness more appropriate local reactivity descriptors than the dual descriptor and the Fukui function, respectively? J. Math. Chem. 2023, 62, 461–475, Erratum in: J. Math. Chem. 2024, 62, 1520; Erratum in: J. Math. Chem. 2024, 62, 1779; Erratum in: J. Math. Chem. 2024, 62, 2368–2369.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M.; Bowling, P.E.; Herbert, J.M. Comment on “Benchmarking Basis Sets for Density Functional Theory Thermochemistry Calculations: Why Unpolarized Basis Sets and the Polarized 6-311G Family Should Be Avoided”. J. Phys. Chem. A 2024, 128, 7739–7745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Süß, D.; Sukuba, I.; Schauperl, M.; Probst, M.; Maihom, T.; Kaiser, A. Performance of DFT functionals for properties of small molecules containing beryllium, tungsten and hydrogen. Nucl. Mater. Energy 2020, 22, 100731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Holguín, N.; Frau, J.; Glossman-Mitnik, D. Exploring the Chemical and Pharmaceutical Potential of Kapakahines A–G Using Conceptual Density Functional Theory-Based Computational Peptidology. Computation 2025, 13, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben El Ayouchia, H.; Anane, H.; El Idrissi Moubtassim, M.L.; Domingo, L.R.; Julve, M.; Stiriba, S.E. A Theoretical Study of the Relationship between the Electrophilicity omega Index and Hammett Constant sigma(p) in [3+2] Cycloaddition Reactions of Aryl Azide/Alkyne Derivatives. Molecules 2016, 21, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, M. An overview of conceptual-DFT based insights into global chemical reactivity of volatile sulfur compounds (VSCs). Comput. Toxicol. 2024, 29, 100295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, R.; Chattaraj, P.K. Chemical reactivity from a conceptual density functional theory perspective. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2021, 98, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zermeno-Macias, M.L.; Gonzalez-Chavez, M.M.; Mendez, F.; Gonzalez-Chavez, R.; Richaud, A. Theoretical Reactivity Study of Indol-4-Ones and Their Correlation with Antifungal Activity. Molecules 2017, 22, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.P.; Marchaim, D. Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria: Infection Prevention and Control Update. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 35, 969–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougan, G.; Baker, S. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi and the pathogenesis of typhoid fever. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 68, 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabrega, A.; Vila, J. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium skills to succeed in the host: Virulence and regulation. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 26, 308–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, Y.; Shimoda, S.; Shimono, N. Current epidemiology, genetic evolution and clinical impact of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018, 61, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, J.; Hu, Q.; Rao, X. Morganella morganii, a non-negligent opportunistic pathogen. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 50, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevermann, J.; Silva, A.; Otero, C.; Oyarzun, D.P.; Barrera, B.; Gil, F.; Calderon, I.L.; Fuentes, J.A. Identification of Genes Involved in Biogenesis of Outer Membrane Vesicles (OMVs) in Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhi. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, Z.; Fei, X.; Tian, Y.; Zhou, G.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Shi, H. The role of TolA, TolB, and TolR in cell morphology, OMVs production, and virulence of Salmonella Choleraesuis. AMB Express 2022, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, R.P.; Record, K.E. Gram-Negative Bacteria. In Management of Antimicrobials in Infectious Diseases; Mainous, A.G., Pomeroy, C., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, S.M.; Lambert, P.A.; Rycroft, A.N. The Envelope of Gram-Negative Bacteria. In The Bacterial Cell Surface; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1984; pp. 57–118. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, E.R.; Billings, G.; Odermatt, P.D.; Auer, G.K.; Zhu, L.; Miguel, A.; Chang, F.; Weibel, D.B.; Theriot, J.A.; Huang, K.C. The outer membrane is an essential load-bearing element in Gram-negative bacteria. Nature 2018, 559, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Begum, F.; Rabaan, A.A.; Aljeldah, M.; Al Shammari, B.R.; Alawfi, A.; Alshengeti, A.; Sulaiman, T.; Khan, A. Classification and Multifaceted Potential of Secondary Metabolites Produced by Bacillus subtilis Group: A Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raabe, V.N.; Shane, A.L. Group B Streptococcus (Streptococcus agalactiae). Microbiol. Spectr. 2019, 7, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jespersen, M.G.; Lacey, J.A.; Tong, S.Y.C.; Davies, M.R. Global genomic epidemiology of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020, 86, 104609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beganovic, M.; Luther, M.K.; Rice, L.B.; Arias, C.A.; Rybak, M.J.; LaPlante, K.L. A Review of Combination Antimicrobial Therapy for Enterococcus faecalis Bloodstream Infections and Infective Endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 67, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, S.Y.; Davis, J.S.; Eichenberger, E.; Holland, T.L.; Fowler, V.G., Jr. Staphylococcus aureus infections: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 603–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eltwisy, H.O.; Twisy, H.O.; Hafez, M.H.; Sayed, I.M.; El-Mokhtar, M.A. Clinical Infections, Antibiotic Resistance, and Pathogenesis of Staphylococcus haemolyticus. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olchowik-Grabarek, E.; Mies, F.; Sekowski, S.; Dubis, A.T.; Laurent, P.; Zamaraeva, M.; Swiecicka, I.; Shlyonsky, V. Enzymatic synthesis and characterization of aryl iodides of some phenolic acids with enhanced antibacterial properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2022, 1864, 184011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kratky, M.; Dzurkova, M.; Janousek, J.; Konecna, K.; Trejtnar, F.; Stolarikova, J.; Vinsova, J. Sulfadiazine Salicylaldehyde-Based Schiff Bases: Synthesis, Antimicrobial Activity and Cytotoxicity. Molecules 2017, 22, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.P.; Lv, P.C.; Shi, L.; Zhu, H.L. Design, synthesis, and pharmacological investigation of iodined salicylimines, new prototypes of antimicrobial drug candidates. Arch. Pharm. 2010, 343, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.-P.; Shi, L.; Lv, P.-C.; Li, X.-L.; Zhu, H.-L. Synthesis and antimicrobial activities of metal(II) complexes with bis(2,4-diiodo-6-propyliminomethyl-phenol)-pyridine. J. Coord. Chem. 2009, 62, 3198–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.A.; Oliveira, A.P.A.; Franco, L.L.; Ferencs, M.O.; Ferreira, J.F.G.; Bachi, S.; Speziali, N.L.; Farias, L.M.; Magalhaes, P.P.; Beraldo, H. 5-Nitroimidazole-derived Schiff bases and their copper(II) complexes exhibit potent antimicrobial activity against pathogenic anaerobic bacteria. Biometals 2018, 31, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buddle, J.E.; Fagan, R.P. Pathogenicity and virulence of Clostridioides difficile. Virulence 2023, 14, 2150452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, W.; Jiang, H.; Liu, S.J. The Ambiguous Correlation of Blautia with Obesity: A Systematic Review. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, M.R.; Ly, A.M.; Handford, M.J.; Ramos, D.P.; Pye, C.R.; Furukawa, A.; Klein, V.G.; Noland, R.P.; Edmondson, Q.; Turmon, A.C.; et al. Lipophilic Permeability Efficiency Reconciles the Opposing Roles of Lipophilicity in Membrane Permeability and Aqueous Solubility. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 11169–11182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Gulyas, K.V.; Li, J.; Ma, M.; Zhou, L.; Wu, L.; Xiong, R.; Erdelyi, M.; Zhu, W.; Xu, Z. Unexpected effect of halogenation on the water solubility of small organic compounds. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 172, 108209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavallo, G.; Metrangolo, P.; Milani, R.; Pilati, T.; Priimagi, A.; Resnati, G.; Terraneo, G. The Halogen Bond. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 2478–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcken, R.; Zimmermann, M.O.; Lange, A.; Joerger, A.C.; Boeckler, F.M. Principles and applications of halogen bonding in medicinal chemistry and chemical biology. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 1363–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haase, A.A.; Markham, S.A.; Murakami, H.A.; Hagan, J.; Kostenkova, K.; Koehn, J.T.; Uslan, C.; Beuning, C.N.; Brandenburg, L.; Zadrozny, J.M.; et al. Halogenated non-innocent vanadium(v) Schiff base complexes: Chemical and anti-proliferative properties. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 12893–12911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, S.V.; Tosic, M.; Simic, M.G. Use of the Hammett correlation and.delta.+ for calculation of one-electron redox potentials of antioxidants. J. Phys. Chem. 2002, 95, 10824–10827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delcour, A.H. Outer membrane permeability and antibiotic resistance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1794, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, C.; Hassan, K.A. The Gram-negative permeability barrier: Tipping the balance of the in and the out. mBio 2023, 14, e0120523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Nagarajan, A.; Uchil, P.D. Analysis of Cell Viability by the MTT Assay. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2018, 2018, pdb-prot095505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Caseys, C.; Kliebenstein, D.J. Genetic and molecular landscapes of the generalist phytopathogen Botrytis cinerea. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2024, 25, e13404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreno, A.; Paez-Hernandez, D.; Cantero-Lopez, P.; Zuniga, C.; Nevermann, J.; Ramirez-Osorio, A.; Gacitua, M.; Oyarzun, P.; Saez-Cortez, F.; Polanco, R.; et al. Structural Characterization, DFT Calculation, NCI, Scan-Rate Analysis and Antifungal Activity against Botrytis cinerea of (E)-2-[(2-Aminopyridin-2-yl)imino]-methyl-4,6-di-tert-butylphenol (Pyridine Schiff Base). Molecules 2020, 25, 2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreño, A.; Gacitúa, M.; Páez-Hernández, D.; Polanco, R.; Preite, M.; Fuentes, J.A.; Mora, G.C.; Chávez, I.; Arratia-Pérez, R. Spectral, theoretical characterization and antifungal properties of two phenol derivative Schiff bases with an intramolecular hydrogen bond. New J. Chem. 2015, 39, 7822–7831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, J.B. Fluorescence Quantum Yield Measurements. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. A Phys. Chem. 1976, 80 A, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbancioc, G.; Mangalagiu, I.I.; Moldoveanu, C. A Review on the Synthesis of Fluorescent Five- and Six-Membered Ring Azaheterocycles. Molecules 2022, 27, 6321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Poblete, M.; Carreño, A.; Gacitúa, M.; Páez-Hernández, D.; Rabanal-León, W.A.; Arratia-Pérez, R. Electrochemical behaviors and relativistic DFT calculations to understand the terminal ligand influence on the [Re6(μ3-Q)8X6]4− clusters. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 5471–5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. A 2008, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, P.A.; McKinnon, J.J.; Parsons, S.; Pidcock, E.; Spackman, M.A. Analysis of the compression of molecular crystal structures using Hirshfeld surfaces. CrystEngComm 2008, 10, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakavoli, M.; Rahimizadeh, M.; Feizyzadeh, B.; Kaju, A.A.; Takjoo, R. 3,6-Di(p-chlorophenyl)-2,7-dihydro-1,4,5-thiadiazepine: Crystal Structure and Decoding Intermolecular Interactions with Hirshfeld Surface Analysis. J. Chem. Crystallogr. 2010, 40, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, J.J.; Spackman, M.A.; Mitchell, A.S. Novel tools for visualizing and exploring intermolecular interactions in molecular crystals. Acta Crystallogr. B 2004, 60, 627–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, J.J.; Mitchell, A.S.; Spackman, M.A. Hirshfeld Surfaces: A New Tool for Visualising and Exploring Molecular Crystals. Chem. A Eur. J. 1998, 4, 2136–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F.H.; Kennard, O.; Watson, D.G.; Brammer, L.; Orpen, A.G.; Taylor, R. Tables of bond lengths determined by X-ray and neutron diffraction. Part 1. Bond lengths in organic compounds. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1987, S1–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, C.; Ugalde, J.A.; Mora, G.C.; Alvarez, S.; Contreras, I.; Santiviago, C.A. Draft Genome Sequence of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhi Strain STH2370. Genome Announc. 2014, 2, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jofre, M.R.; Rodriguez, L.M.; Villagra, N.A.; Hidalgo, A.A.; Mora, G.C.; Fuentes, J.A. RpoS integrates CRP, Fis, and PhoP signaling pathways to control Salmonella Typhi hlyE expression. BMC Microbiol 2014, 14, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Moore, C.B.; Barchiesi, F.; Bille, J.; Chryssanthou, E.; Denning, D.W.; Donnelly, J.P.; Dromer, F.; Dupont, B.; Rex, J.H.; et al. Multicenter evaluation of the reproducibility of the proposed antifungal susceptibility testing method for fermentative yeasts of the Antifungal Susceptibility Testing Subcommittee of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AFST-EUCAST). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2003, 9, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.N.; McBride, S.M. Isolating and Purifying Clostridium difficile Spores. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1476, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzel, D.; McBride, S.M. The Impact of pH on Clostridioides difficile Sporulation and Physiology. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e02706-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queralto, C.; Ortega, C.; Diaz-Yanez, F.; Inostroza, O.; Espinoza, G.; Alvarez, R.; Gonzalez, R.; Parra, F.; Paredes-Sabja, D.; Acuna, L.G.; et al. The chaperone ClpC participates in sporulation, motility, biofilm, and toxin production of Clostridioides difficile. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 33, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inostroza, O.; Fuentes, J.A.; Yanez, P.; Espinoza, G.; Fica, O.; Queralto, C.; Rodriguez, J.; Flores, I.; Gonzalez, R.; Soto, J.A.; et al. Characterization of Clostridioides difficile Persister Cells and Their Role in Antibiotic Tolerance. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazonova, E.V.; Chesnokov, M.S.; Zhivotovsky, B.; Kopeina, G.S. Drug toxicity assessment: Cell proliferation versus cell death. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staats, M.; van Kan, J.A. Genome update of Botrytis cinerea strains B05.10 and T4. Eukaryot. Cell 2012, 11, 1413–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cai, Y.; Liang, Y.; Ji, P.; Xu, L. Assessment of antifungal activities of a biocontrol bacterium BA17 for managing postharvest gray mold of green bean caused by Botrytis cinerea. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2020, 161, 111086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenouche, S.; Sandoval-Yañez, C.; Martínez-Araya, J.I. The antioxidant capacity of myricetin. A molecular electrostatic potential analysis based on DFT calculations. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2022, 801, 139708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaji, B.; Singh, P.; Skelton, A.A.; Martincigh, B.S. A density functional theory study of a series of symmetric dibenzylideneacetone analogues as potential chemical UV-filters. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound | Solvent | λmax, nm | ε, mol−1 dm3 cm−1 | Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SB-3 | MeOH | 278 392 | 5182.00 4950.88 | n → π * and π → π * π → π * |

| SB-4 | MeOH | 279 393 | 16,293.16 5587.50 | n → π * and π → π * π → π * |

| SB-5 | MeOH | 282 395 | 5493.82 6274.50 | n → π * and π → π * π → π * |

| SB-3 | DMSO | 287 410 | 13,731.67 14,869.74 | n → π * and π → π * π → π * |

| SB-4 | DMSO | 288 407 | 17,347.46 5571.82 | n → π * and π → π * π → π * |

| SB-5 | DMSO | 290 407 | 17,415.71 17,439.92 | n → π * and π → π * π → π * |

| Compound | SB-5 |

|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C14H10I2N2O3 |

| Formula weight (g mol−1) | 508.04 |

| Temperature (K) | 296.15 |

| Crystal system | monoclinic |

| Space group | P21/c |

| a (Å) | 15.9861 (12) |

| b (Å) | 4.6188 (4) |

| c (Å) | 27.612 (2) |

| α (°) | 90 |

| β (°) | 105.867 (3) |

| γ (°) | 90 |

| Volume (Å3) | 1961.1 (3) |

| Z | 4 |

| ρcalc (g cm−3) | 1.721 |

| μ (mm−1) | 3.215 |

| F (000) | 952.0 |

| Crystal size (mm3) | 0.075 × 0.017 × 0.014 |

| Radiation | MoKα (λ = 0.71073) |

| 2Θ range for data collection (°) | 3.066 to 50 |

| Index ranges | −19 ≤ h ≤ 19, −5 ≤ k ≤ 5, −32 ≤ l ≤ 32 |

| Reflections collected | 42,895 |

| Independent reflections | 3460 [Rint = 0.1428, Rsigma = 0.0611] |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 3460/0/193 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.097 |

| Final R indexes [I ≥ 2σ (I)] | R1 = 0.0579, wR2 = 0.1530 |

| Final R indexes [all data] | R1 = 0.1130, wR2 = 0.1877 |

| Largest diff. peak/hole/e Å−3 | 1.44/−0.63 |

| D-H⋅⋅⋅A | D-H (Å) | H⋅⋅⋅A (Å) | D⋅⋅⋅A (Å) | ∠D-H⋅⋅⋅A (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O(1)-H(1)⋅⋅⋅N(1) | 0.82 | 1.80 | 2.529 (11) | 148.0 |

| O(3)-H(3)⋅⋅⋅O(2) 1 | 0.82 | 1.81 | 2.616 (10) | 168.4 |

| N(2)-H(2B)⋅⋅⋅O(1) 2 | 0.86 | 2.18 | 2.965 (11) | 152.4 |

| Compound | Ox i(irr) | Red i(rev) |

|---|---|---|

| SB-3 | 0.98 V | −1.05 V |

| SB-4 | 1.04 V | −1.04 V |

| SB-5 | 1.02 V | −1.06 V |

| Species | Precursor 1 | MIC Precursor 1 (µM) | Precursor 2 | MIC Precursor 2 (µM) | Aminobenzoic Acid-Derived Schiff Base | MIC Aminobenzoic Acid-Derived Schiff Base (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus subtilis | 3,5-dichlorosalicyaldehide | No effect | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-3 | No effect |

| 3,5-dibromo-2-hydroxybenzaldehyde | No effect | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-4 | No effect | |

| 2-hydroxy-3,5-diiodobenzaldehyde | 6.3 ± 0.0 | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-5 | 12.6 ± 0.0 | |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 3,5-dichlorosalicyaldehide | 25.3 ± 0.0 | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-3 | No effect |

| 3,5-dibromo-2-hydroxybenzaldehyde | 17.3 ± 2.3 | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-4 | 25.3 ± 0.0 | |

| 2-hydroxy-3,5-diiodobenzaldehyde | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-5 | 6.3 ± 1.0 | |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 3,5-dichlorosalicyaldehide | 20.5 ± 2.3 | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-3 | 20.5 ± 2.3 |

| 3,5-dibromo-2-hydroxybenzaldehyde | 9.4 ± 1.1 | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-4 | 5.5 ± 0.5 | |

| 2-hydroxy-3,5-diiodobenzaldehyde | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-5 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 3,5-dichlorosalicyaldehide | 50.5 ± 0.0 | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-3 | No effect |

| 3,5-dibromo-2-hydroxybenzaldehyde | 50.5 ± 0.0 | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-4 | No effect | |

| 2-hydroxy-3,5-diiodobenzaldehyde | 10.2 ± 1.1 | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-5 | 14.1 ± 1.5 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus strain 2 | 3,5-dichlorosalicyaldehide | No effect | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-3 | No effect |

| 3,5-dibromo-2-hydroxybenzaldehyde | 12.6 ± 0.0 | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-4 | No effect | |

| 2-hydroxy-3,5-diiodobenzaldehyde | 6.3 ± 0.0 | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-5 | 12.6 ± 0.0 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus strain 6 | 3,5-dichlorosalicyaldehide | 50.5 ± 0.0 | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-3 | No effect |

| 3,5-dibromo-2-hydroxybenzaldehyde | 11.8 ± 0.7 | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-4 | No effect | |

| 2-hydroxy-3,5-diiodobenzaldehyde | 6.3 ± 0.0 | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-5 | 8.6 ± 1.1 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus strain 7 | 3,5-dichlorosalicyaldehide | No effect | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-3 | No effect |

| 3,5-dibromo-2-hydroxybenzaldehyde | 12.6 ± 0.0 | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-4 | No effect | |

| 2-hydroxy-3,5-diiodobenzaldehyde | 6.3 ± 0.0 | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-5 | 8.6 ± 1.1 | |

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus | 3,5-dichlorosalicyaldehide | No effect | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-3 | No effect |

| 3,5-dibromo-2-hydroxybenzaldehyde | No effect | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-4 | No effect | |

| 2-hydroxy-3,5-diiodobenzaldehyde | 12.6 ± 0.0 | 3,4-diaminobenzoic | No effect | SB-5 | 14.1 ± 1.5 |

| Bacteria | SB-3 | SB-4 | SB-5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clostridioides difficile | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| Blautia coccoides | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 0.01 ± 0.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carreño, A.; Artigas, V.; Gómez-Arteaga, B.; Ancede-Gallardo, E.; Cepeda-Plaza, M.; Martínez-Araya, J.I.; Arce, R.; Gacitúa, M.; Videla, C.; Preite, M.; et al. Synthesis, Physicochemical Characterization, and Biocidal Evaluation of Three Novel Aminobenzoic Acid-Derived Schiff Bases Featuring Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110801

Carreño A, Artigas V, Gómez-Arteaga B, Ancede-Gallardo E, Cepeda-Plaza M, Martínez-Araya JI, Arce R, Gacitúa M, Videla C, Preite M, et al. Synthesis, Physicochemical Characterization, and Biocidal Evaluation of Three Novel Aminobenzoic Acid-Derived Schiff Bases Featuring Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(21):10801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110801

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarreño, Alexander, Vania Artigas, Belén Gómez-Arteaga, Evys Ancede-Gallardo, Marjorie Cepeda-Plaza, Jorge I. Martínez-Araya, Roxana Arce, Manuel Gacitúa, Camila Videla, Marcelo Preite, and et al. 2025. "Synthesis, Physicochemical Characterization, and Biocidal Evaluation of Three Novel Aminobenzoic Acid-Derived Schiff Bases Featuring Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 21: 10801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110801

APA StyleCarreño, A., Artigas, V., Gómez-Arteaga, B., Ancede-Gallardo, E., Cepeda-Plaza, M., Martínez-Araya, J. I., Arce, R., Gacitúa, M., Videla, C., Preite, M., Otero, M. C., Guerra, C., Polanco, R., Fuentes, I., Marchant, P., Inostroza, O., Gil, F., & Fuentes, J. A. (2025). Synthesis, Physicochemical Characterization, and Biocidal Evaluation of Three Novel Aminobenzoic Acid-Derived Schiff Bases Featuring Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(21), 10801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110801