Coelenterazine-Dependent Luciferases as a Powerful Analytical Tool for Research and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

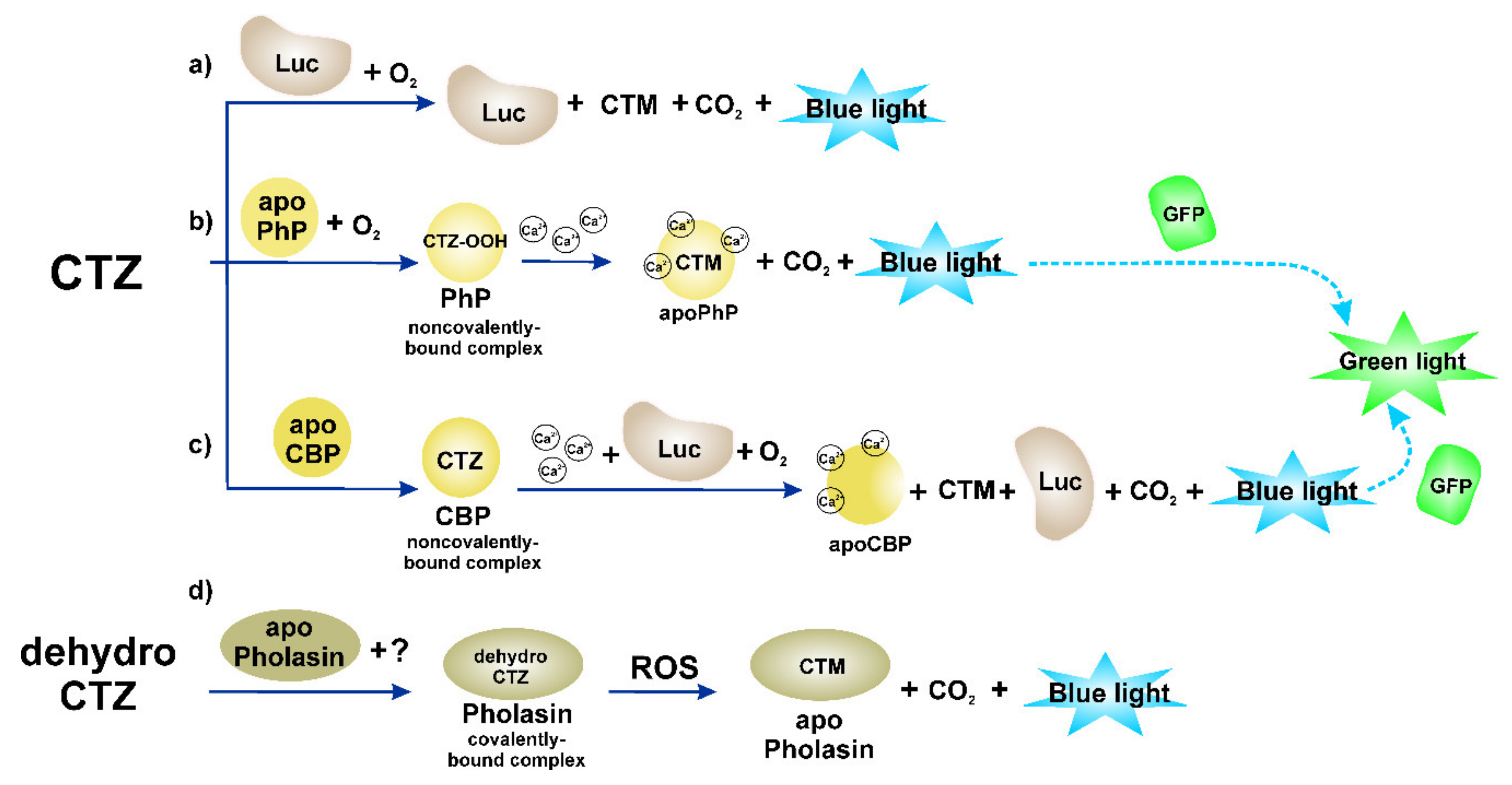

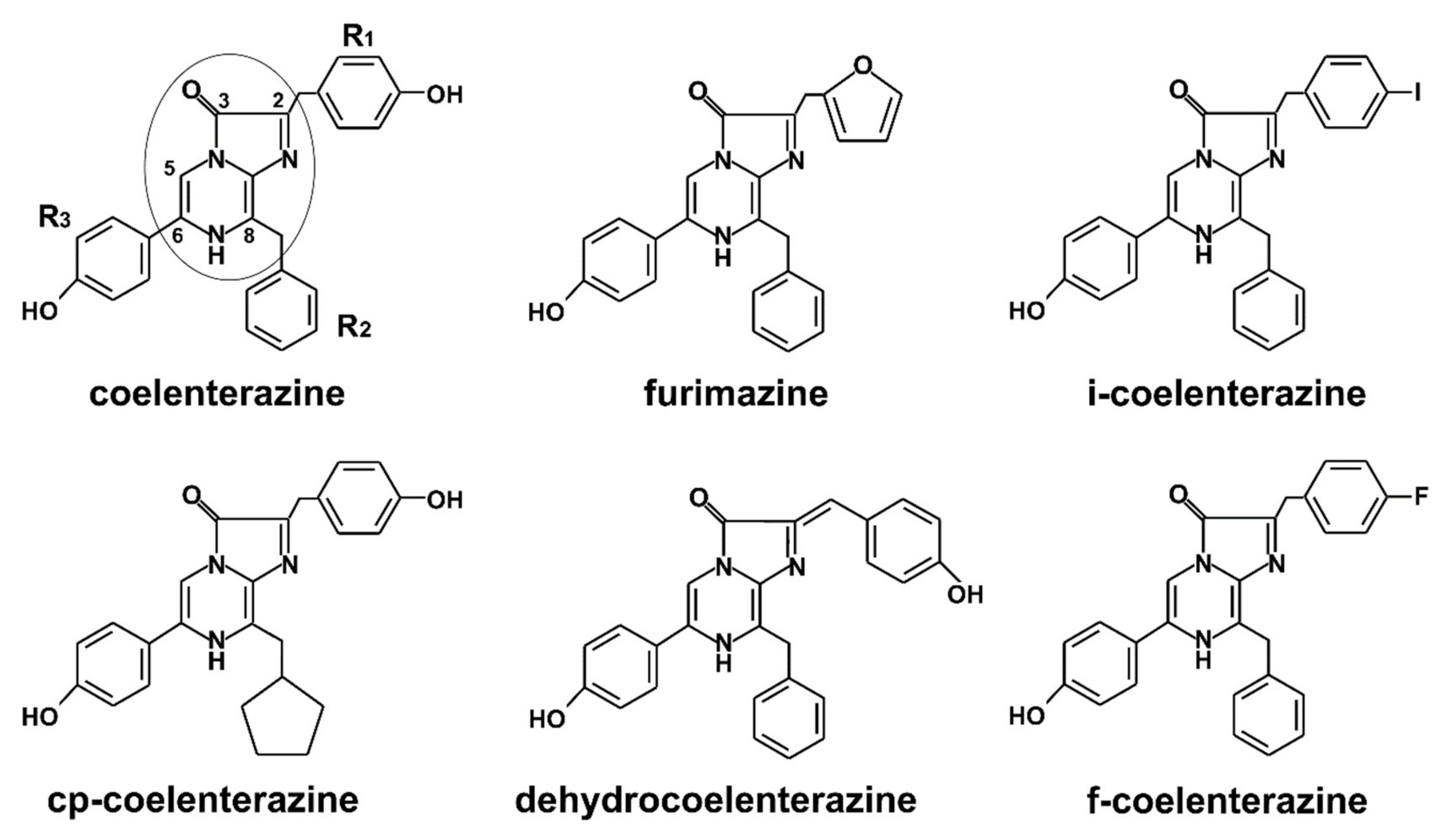

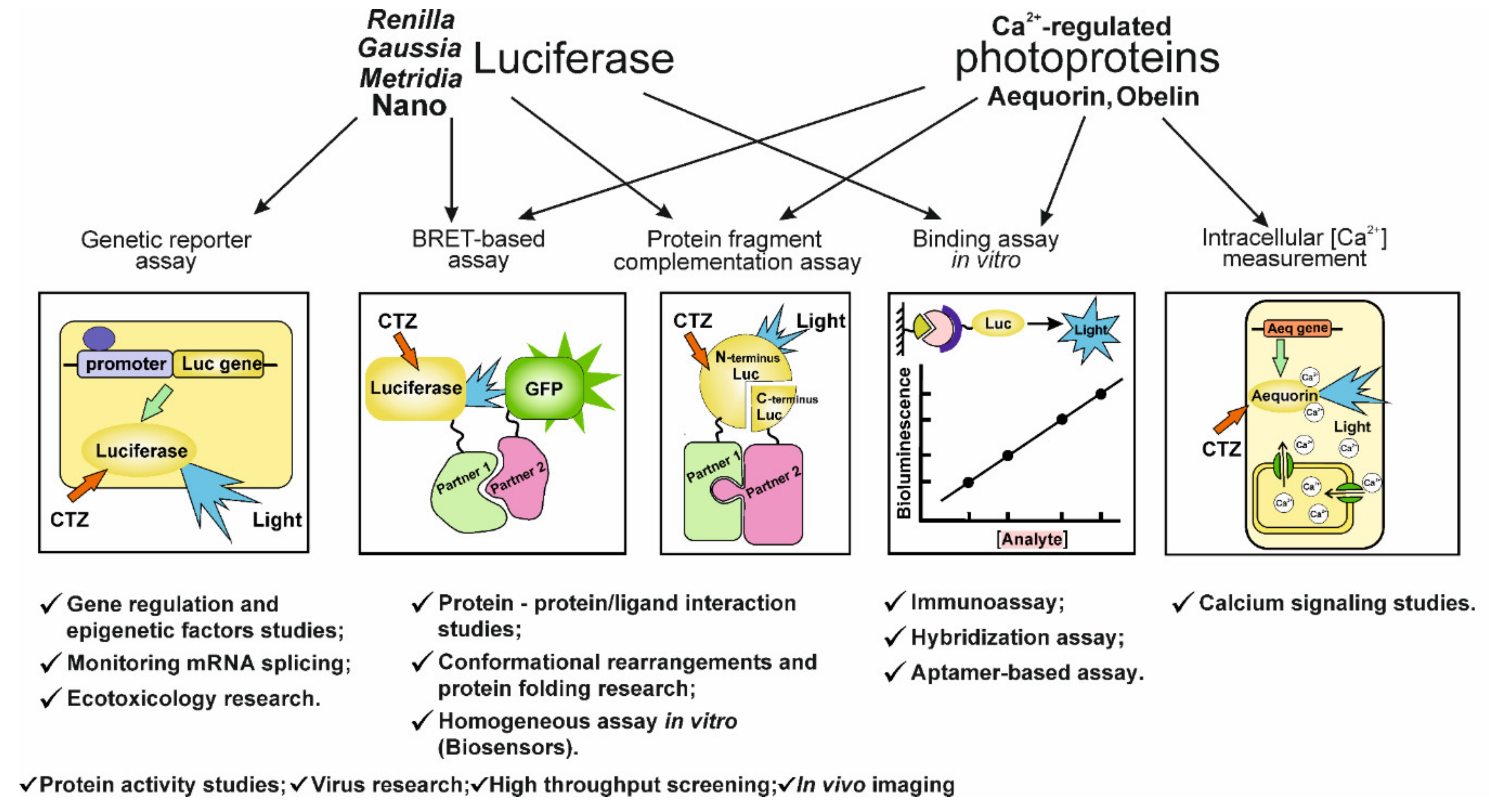

2. Analytical Application of Ca2+-Regulated Photoproteins

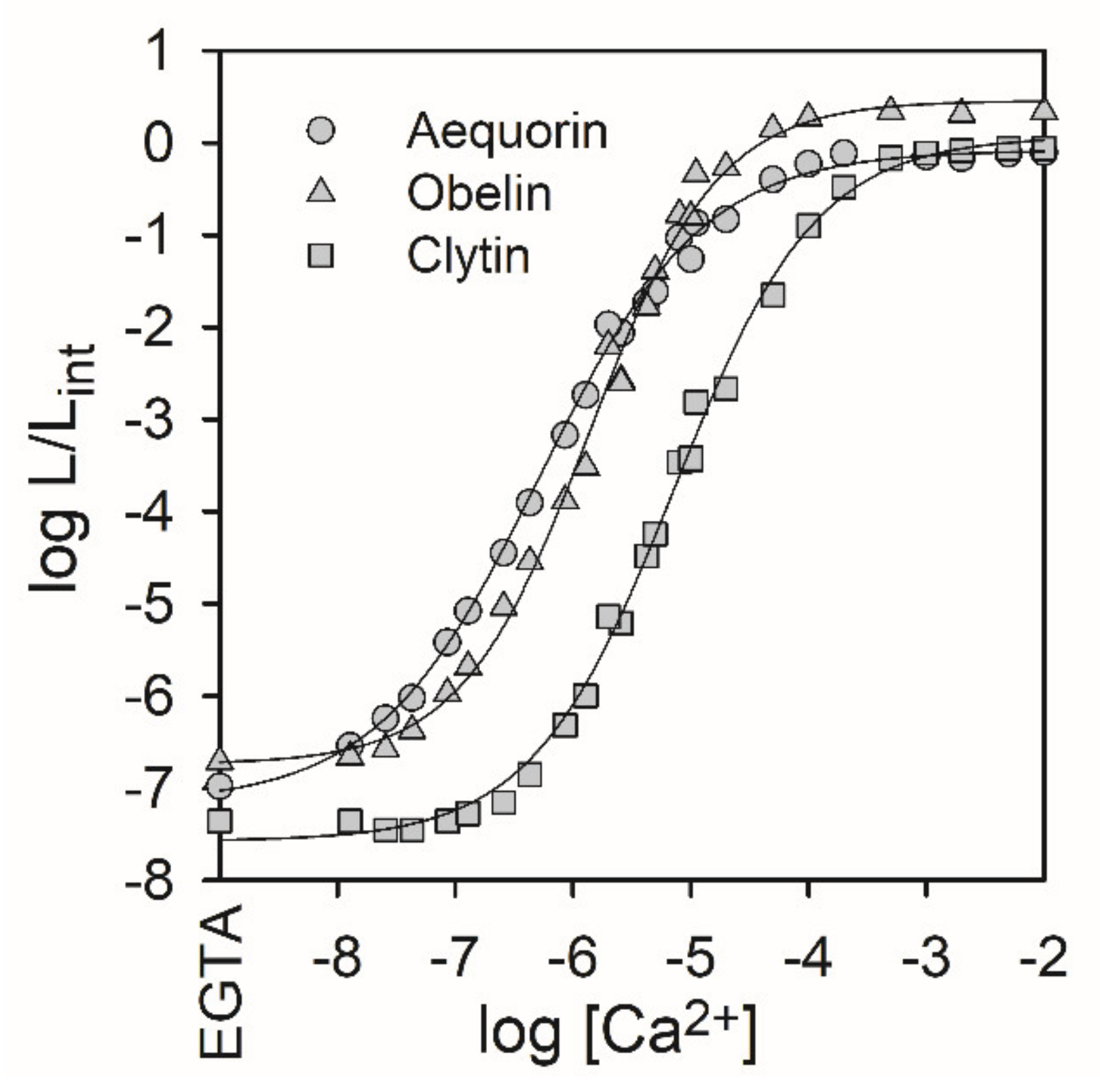

2.1. Ca2+-Regulated Photoproteins as Indicators of Intracellular Ca2+

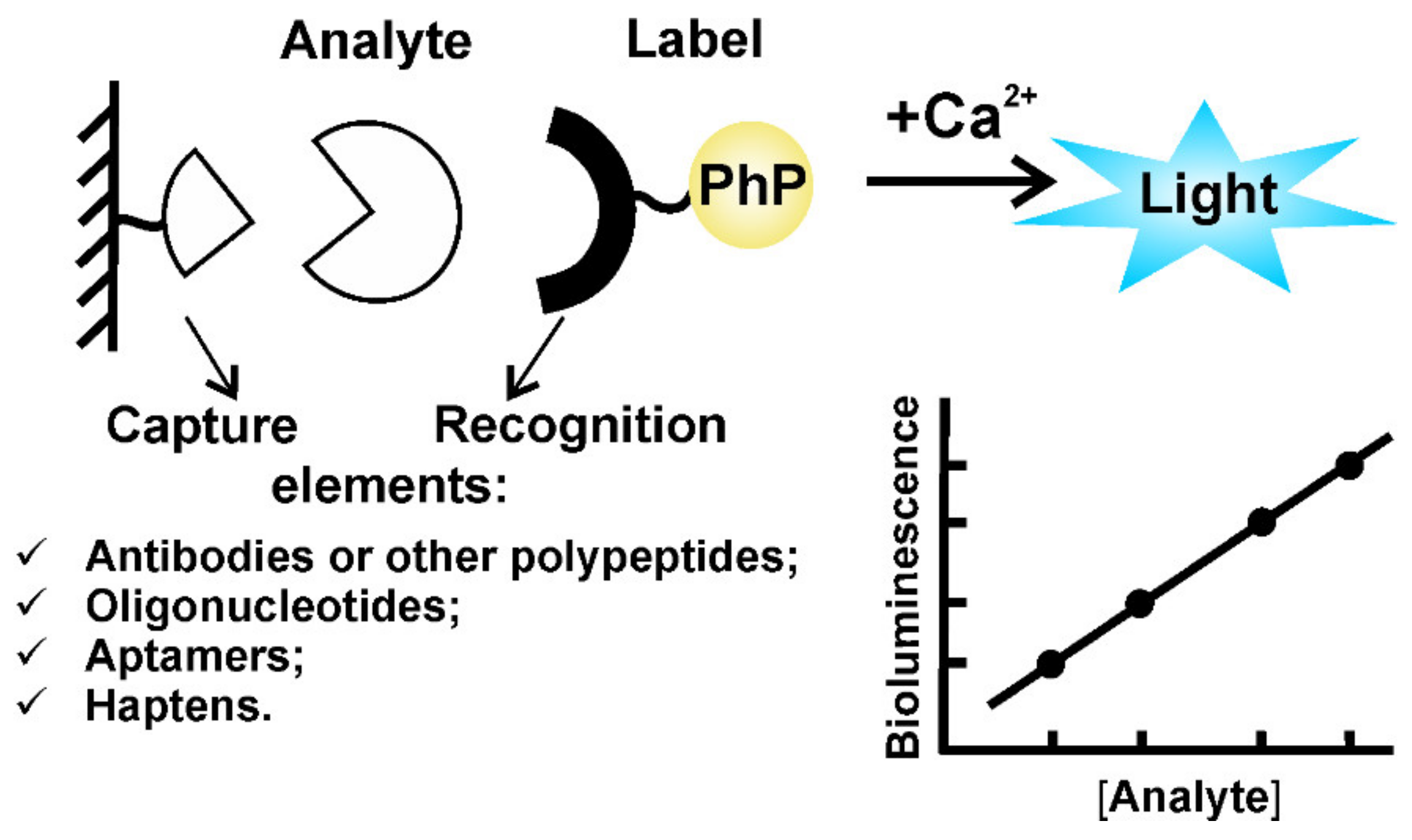

2.2. Ca2+-Regulated Photoproteins as Effective Reporters for In Vitro Binding Assay

2.3. Analysis Based on the Aequorin Bioluminescence Inhibition

3. Photoprotein Pholasin and Its Analytical Application

4. CTZ-Dependent Luciferase Analytical Application

4.1. NanoBit-Based Technologies

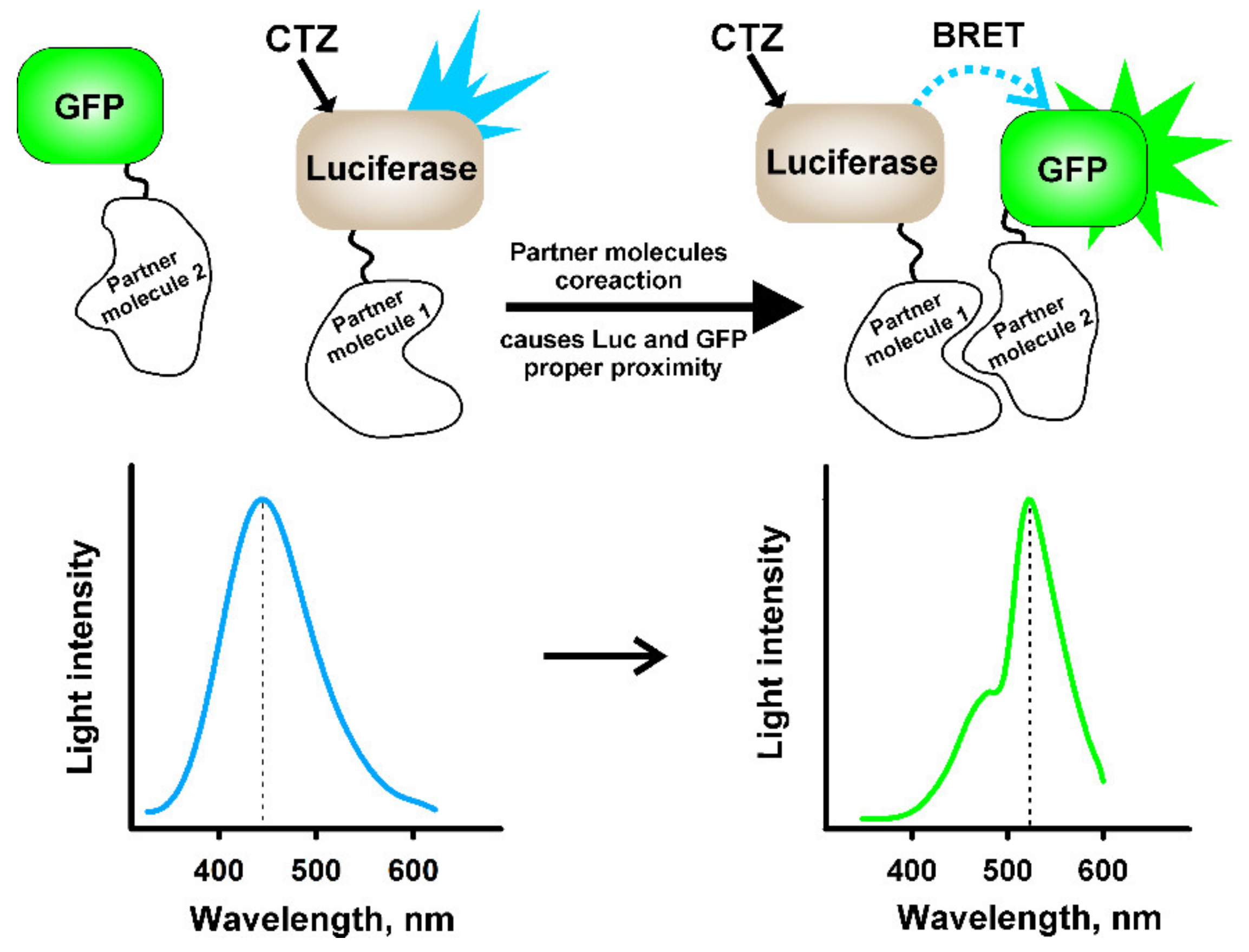

4.2. NanoBRET-Based Technologies

4.3. Application of NanoLuc as a Label for In Vitro Binding Assay

4.4. NanoLuc in Genetic Reporter Assay

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTZ | coelenterazine |

| CTM | coelenteramide, decarboxylated derivative of CTZ |

| Luc | luciferase |

| PhP | Ca2+-regulated photoprotein |

| apoPhP | polypeptide part of PhP |

| CBP | Ca2+-dependent coelenterazine-binding protein |

| apoCBP | polypeptide part of CBP |

| GFP | green fluorescent protein |

| EF-hand | The Ca2+-binding sites formed by helix-loop-helix motifs |

References

- Shimomura, O.; Yampolsky, I. Bioluminescence: Chemical Principles and Methods, 3rd ed.; World Scientific Publishing: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markova, S.V.; Vysotski, E.S. Coelenterazine-dependent luciferases. Biochemistry 2015, 80, 714–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, L.A. Creation of artificial luciferases to expand their analytical potential. Comb. Chem. High. Throughput Screen. 2015, 18, 919–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eremeeva, E.V.; Vysotski, E.S. Exploring bioluminescence function of the Ca2+ -regulated photoproteins with site-directed mutagenesis. Photochem. Photobiol. 2019, 95, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepanyuk, G.A.; Liu, Z.J.; Markova, S.S.; Frank, L.A.; Lee, J.; Vysotski, E.S.; Wang, B.C. Crystal structure of coelenterazine-binding protein from Renilla muelleri at 1.7 A: Why it is not a calcium-regulated photoprotein. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2008, 7, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepanyuk, G.A.; Liu, Z.J.; Vysotski, E.S.; Lee, J.; Rose, J.P.; Wang, B.C. Structure based mechanism of the Ca(2+)-induced release of coelenterazine from the Renilla binding protein. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2009, 74, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titushin, M.S.; Markova, S.V.; Frank, L.A.; Malikova, N.P.; Stepanyuk, G.A.; Lee, J.; Vysotski, E.S. Coelenterazine-binding protein of Renilla muelleri: cDNA cloning, overexpression, and characterization as a substrate of luciferase. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2008, 7, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimomura, O. Membrane permeability of coelenterazine analogues measured with fish eggs. Biochem. J. 1997, 326, 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepanyuk, G.A.; Unch, J.; Malikova, N.P.; Markova, S.V.; Lee, J.; Vysotski, E.S. Coelenterazine-v ligated to Ca2+-triggered coelenterazine-binding protein is a stable and efficient substrate of the red-shifted mutant of Renilla muelleri luciferase. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 398, 1809–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasitskaya, V.V.; Korneeva, S.I.; Kudryavtsev, A.N.; Markova, S.V.; Stepanyuk, G.A.; Frank, L.A. Ca2+-triggered coelenterazine-binding protein from Renilla as an enzyme-dependent label for binding assay. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 401, 2573–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudryavtsev, A.N.; Burakova, L.P.; Frank, L.A. Bioluminescent detection of tick-borne encephalitis virus in native ticks. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 2252–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuse, M. Chromophores in photoproteins of a glowing squid and mollusk. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2014, 78, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimomura, O.; Johnson, F.H.; Saiga, Y. Extraction, purification and properties of aequorin, a bioluminescent protein from the luminous hydromedusan, Aequorea. J. Cell Comp. Physiol. 1962, 59, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimomura, O. Structure of the chromophore of Aequorea green fluorescent protein. FEBS Lett. 1979, 104, 220–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craggs, T.D. Green fluorescent protein: Structure, folding and chromophore maturation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 2865–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teranishi, K. Luminescence of imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-3(7H)-one compounds. Bioorganic Chem. 2007, 35, 82–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.P.; Unch, J.; Binkowski, B.F.; Valley, M.P.; Butler, B.L.; Wood, M.G.; Otto, P.; Zimmerman, K.; Vidugiris, G.; Machleidt, T.; et al. Engineered luciferase reporter from a deep sea shrimp utilizing a novel imidazopyrazinone substrate. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012, 7, 1848–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, G.; Molinari, P.; Ferretti, G.; Cappelli, A.; Anzini, M.; Vomero, S.; Costa, T. New red-shifted coelenterazine analogues with an extended electronic conjugation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 5114–5118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contant, E.P.; Goyard, S.; Hervin, V.; Gagnot, G.; Baatallah, R.; Jacob, Y.; Rose, T.; Janin, Y. Gram-scale synthesis of luciferins derived from coelenterazine and original insight into their bioluminescence properties. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 3709–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contant, E.P.; Gagnot, G.; Hervin, V.; Baatallah, R.; Goyard, S.; Jacob, Y.; Rose, T.; Janin, Y.L. Bioluminescence profiling of NanoKAZ/NanoLuc luciferase using a chemical library of coelenterazine analogues. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 948–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, J.F.; Inouye, S.; Teranishi, K.; Shimomura, O. The crystal structure of the photoprotein aequorin at 2.3 Å resolution. Nature 2000, 405, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.J.; Vysotski, E.S.; Deng, L.; Lee, J.; Rose, J.P.; Wang, B.C. Atomic resolution structure of obelin: Soaking with calcium enhances electron density of the second oxygen atom substituted at the C2-position of coelenterazine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 311, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vysotski, E.S.; Lee, J. Ca2+-regulated photoproteins: Structural insight into the bioluminescence mechanism. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004, 37, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grinstead, K.; Joel, S.; Zingg, J.M.; Dikici, E.; Daunert, S. Enabling aequorin for biotechnology applications through genetic engineering. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2015, 3, 149–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Rowe, L.; Dikici, E.; Ensor, M.; Daunert, S. Aequorin mutants with increased thermostability. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014, 406, 5639–5643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Blinks, J.R. Use of photoproteins as intracellular calcium indicators. Environ. Health Perspect. 1990, 84, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berridge, M.J.; Lipp, P.; Bootman, M.D. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000, 1, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mank, M.; Griesbeck, O. Genetically encoded calcium indicators. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 1550–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottolini, D.; Calì, T.; Brini, M. Measurements of Ca2+ concentration with recombinant targeted luminescent probes. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 937, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonora, M.; Giorgi, C.; Bononi, A.; Marchi, S.; Patergnani, S.; Rimessi, A.; Rizzuto, R.; Pinton, P. Subcellular calcium measurements in mammalian cells using jellyfish photoprotein aequorin-based probes. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 2105–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malikova, N.P.; Burakova, L.P.; Markova, S.V.; Vysotski, E.S. Characterization of hydromedusan Ca2+-regulated photoproteins as a tool for measurement of Ca2+ concentration. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014, 406, 5715–5726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malikova, N.P.; Borgdorff, A.J.; Vysotski, E.S. Semisynthetic photoprotein reporters for tracking fast Ca2+ transients. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2015, 14, 2213–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markova, S.V.; Burakova, L.P.; Golz, S.; Malikova, N.P.; Frank, L.A.; Vysotski, E.S. The light-sensitive photoprotein berovin from the bioluminescent ctenophore Beroe abyssicola: A novel type of Ca2+-regulated photoprotein. FEBS J. 2012, 279, 856–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafarian, V.; Sariri, R.; Hosseinkhani, S.; Aghamaali, M.R.; Sajedi, R.H.; Taghdir, M.; Hassannia, S. A unique EF-hand motif in mnemiopsin photoprotein from Mnemiopsis leidyi: Implication for its low calcium sensitivity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 413, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Fuente, S.; Fonteriz, R.I.; de la Cruz, P.J.; Montero, M.; Alvarez, J. Mitochondrial free [Ca2+] dynamics measured with a novel low-Ca2+ affinity aequorin probe. Biochem. J. 2012, 445, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Fuente, S.; Fonteriz, R.I.; Montero, M.; Alvarez, J. Ca2+ homeostasis in the endoplasmic reticulum measured with a new low-Ca2+-affinity targeted aequorin. Cell Calcium 2013, 54, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinstead, K.M.; Rowe, L.; Ensor, C.M.; Joel, S.; Daftarian, P.; Dikici, E.; Zingg, J.M.; Daunert, S. Red-shifted aequorin variants incorporating non-canonical amino acids: Applications in in vivo imaging. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilian, N.; Shanehsaz, M.; Sajedi, R.H.; Gharaat, M.; Ghahremanzadeh, R. Improving the luminescence properties of aequorin by conjugating to CdSe/ZnS quantum dot nanoparticles: Red shift and slowing decay rate. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2016, 162, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakayan, A.; Domingo, B.; Vaquero, C.F.; Peyriéras, N.; Llopis, J. Fluorescent protein-photoprotein fusions and their applications in calcium imaging. Pflügers Arch. 2015, 467, 2031–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakayan, A.; Domingo, B.; Miyawaki, A.; Llopis, J. Imaging Ca2+ activity in mammalian cells and zebrafish with a novel red-emitting aequorin variant. Pflügers Arch. 2015, 467, 2031–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R.E.; Tour, O.; Palmer, A.E.; Steinbach, P.A.; Baird, G.S.; Zacharias, D.A.; Tsien, R.Y. A monomeric red fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 7877–7882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjarres, I.M.; Chamero, P.; Domingo, B.; Molina, F.; Llopis, J.; Alonso, M.T.; Garcia-Sancho, J. Red and green aequorins for simultaneous monitoring of Ca2+ signals from two different organelles. Pflügers Arch. 2008, 455, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Vicente, M.; Salgado-Almario, J.; Soriano, J.; Burgos, M.; Domingo, B.; Llopis, J. Visualization of mitochondrial Ca2+ signals in skeletal muscle of zebrafish embryos with bioluminescent indicators. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drobac, E.; Tricoire, L.; Chaffotte, A.F.; Guiot, E.; Lambolez, B. Calcium imaging in single neurons from brain slices using bioluminescent reporters. J. Neurosci. Res. 2010, 88, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrero, P.; Richmond, L.; Nitabach, M.; Davies, S.A.; Dow, J.A.T. A biogenic amine and a neuropeptide act identically: Tyramine signals through calcium in Drosophila tubule stellate cells. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 280, 2012–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavot, P.; Carbognin, E.; Martin, J.R. PKA and cAMP/CNG channels independently regulate the cholinergic Ca2+-response of Drosophila mushroom body neurons. eNeuro 2015, 2, e0054-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murmu, M.S.; Stinnakre, J.; Martin, J.R. Presynaptic Ca2+ stores contribute to odor-induced responses in Drosophila olfactory receptor neurons. J. Exp. Biol. 2010, 213, 4163–4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minocci, D.; Carbognin, E.; Murmu, M.S.; Martin, J.R. In vivo functional calcium imaging of induced or spontaneous activity in the fly brain using a GFP-apoaequorin-based bioluminescent approach. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013, 1833, 1632–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marescotti, M.; Lagogiannis, K.; Webb, B.; Davies, R.W.; Armstrong, J.D. Monitoring brain activity and behaviour in freely moving Drosophila larvae using bioluminescence. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, E.A.; Kampff, A.R.; Prober, D.A.; Schier, A.F.; Engert, F. Monitoring neural activity with bioluminescence during natural behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 2010, 13, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.Y.; Webb, S.E.; Love, D.R.; Miller, A.L. Visualization, characterization and modulation of calcium signaling during the development of slow muscle cells in intact zebrafish embryos. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2011, 55, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, S.E.; Cheung, C.C.Y.; Chan, C.M.; Love, D.R.; Miller, A.L. Application of complementary luminescent and fluorescent imaging techniques to visualize nuclear and cytoplasmic Ca2+ signalling during the in vivo differentiation of slow muscle cells in zebrafish embryos under normal and dystrophic conditions. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2012, 39, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelu, J.J.; Chan, H.L.; Webb, S.E.; Cheng, A.H.; Ruas, M.; Parrington, J.; Galione, A.; Miller, A.L. Two-pore channel 2 activity is required for slow muscle cell-generated Ca2+ signaling during myogenesis in intact zebrafish. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2015, 59, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, S.E.; Miller, A.L. The use of complementary luminescent and fluorescent techniques for imaging Ca2+ signaling events during the early development of Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1929, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, H.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, S.; Lu, L. The claudin family protein FigA mediates Ca2+ homeostasis in response to extracellular stimuli in Aspergillus nidulans and Aspergillus fumigatus. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Feng, Y.; Liang, G.; Liu, N.; Zhu, J.K. Aequorin-based luminescence imaging reveals stimulus- and tissue-specific Ca2+ dynamics in Arabidopsis plants. Mol. Plant. 2013, 6, 444–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.; Dauphin, A.; Meimoun, P.; Kadono, T.; Nguyen, H.T.H.; Arbelet-Bonnin, D.; Zhao, T.; Errakhi, R.; Lehner, A.; Kawano, T.; et al. Methanol induces cytosolic calcium variations, membrane depolarization and ethylene production in arabidopsis and tobacco. Ann. Bot. 2018, 122, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Taylor, J.L.; He, Y.; Ni, J. Enlightenment on the aequorin-based platform for screening Arabidopsis stress sensory channels related to calcium signaling. Plant. Signal. Behav. 2015, 10, e1057366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sello, S.; Moscatiello, R.; Mehlmer, N.; Leonardelli, M.; Carraretto, L.; Cortese, E.; Zanella, F.G.; Baldan, B.; Szabò, I.; Vothknecht, U.C.; et al. Chloroplast Ca2+ fluxes into and across thylakoids revealed by thylakoid-targeted aequorin probes. Plant. Physiol. 2018, 177, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroz, N.; Tanaka, K. FlgII-28 is a major flagellin-derived defense elicitor in potato. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 2020, 33, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyena, H.T.H.; Bouteaub, F.; Mazarsd, C.; Kusee, M.; Kawano, T. Enhanced elevations of hypo-osmotic shock-induced cytosolic and nucleic calcium concentrations in tobacco cells by pretreatment with dimethyl sulfoxide. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2019, 83, 318–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscatiello, R.; Sello, S.; Ruocco, M.; Barbulova, A.; Cortese, E.; Nigris, S.; Baldan, B.; Chiurazzi, M.; Mariani, P.; Lorito, M.; et al. The hydrophobin HYTLO1 secreted by the biocontrol fungus trichoderma longibrachiatum triggers a NAADP-mediated calcium signalling pathway in Lotus japonicus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruta, L.L.; Nicolau, I.; Popa, C.V.; Farcasanu, I.C. Manganese suppresses the haploinsufficiency of heterozygous trpy1D/TRPY1 Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells and stimulates the TRPY1-dependent release of vacuolar Ca2+ under H2O2 Stress. Cells 2019, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brochet, M.; Collins, M.O.; Smith, T.K.; Thompson, E.; Sebastian, S.; Volkmann, K.; Schwach, F.; Chappell, L.; Gomes, A.R.; Berriman, M.; et al. Phosphoinositide metabolism links cGMP-dependent protein kinase G to essential Ca2+ signals at key decision points in the life cycle of Malaria parasites. PLoS Biol. 2014, 12, e100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, L.A. Ca2+-regulated photoproteins: Effective immunoassay reporters. Sensors 2010, 10, 11287–11300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasitskaya, V.V.; Frank, L.A. Application of enzyme bioluminescence for medical diagnostics. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2014, 144, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daunert, S.; Deo, S.K. Photoproteins in Bioanalysis; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L.A.; Borisova, V.V.; Markova, S.V.; Malikova, N.P.; Stepanyuk, G.A.; Vysotski, E.S. Violet and greenish photoprotein obelin mutants for reporter applications in dual-color assay. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008, 391, 2891–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasitskaya, V.V.; Kudryavtsev, A.N.; Shimomura, O.; Frank, L.A. Obelin mutants as reporters in bioluminescent dual-analyte binding assay. Anal. Methods 2013, 5, 636–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudryavtsev, A.N.; Krasitskaya, V.V.; Petunin, A.I.; Burakov, A.Y.; Frank, L.A. Simultaneous bioluminescent immunoassay of serum total and IgG-bound prolactins. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 3119–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashmakova, E.E.; Krasitskaya, V.V.; Frank, L.A. Simultaneous genotyping of four single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with risk factors of hemostasis disorders. Comb. Chem. High. Throughput Screen. 2015, 18, 930–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashmakova, E.E.; Krasitskaya, V.V.; Bondar, A.A.; Kozlova, A.V.; Ruksha, T.G.; Frank, L.A. Bioluminescent assay to detect melanocortin-1 receptor (MC1R) polymorphisms (R160W, R151C, and D294H). Mol. Biol. 2015, 49, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashmakova, E.E.; Krasitskaya, V.V.; Bondar, A.A.; Eremina, E.N.; Slepov, E.V.; Zukov, R.A.; Frank, L.A. Bioluminescent SNP genotyping technique: Development and application for detection of melanocortin 1 receptor gene polymorphisms. Talanta 2018, 189, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Scott, D.; Dikici, E.; Joel, S.; Deo, S.; Daunert, S. Multiplexing cytokine analysis: Towards reducing sample volume needs in clinical diagnostics. Analyst 2019, 144, 3250–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inouye, S.; Sato, J. Purification of histidine-tagged aequorin with a reactive cysteine residue for chemical conjugations and its application for bioluminescent sandwich immunoassays. Protein Expr. Purif. 2012, 83, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasitskaya, V.V.; Burakova, L.P.; Komarova, A.A.; Bashmakova, E.E.; Frank, L.A. Mutants of Ca2+-regulated photoprotein obelin for site-specific conjugation. Photochem. Photobiol. 2017, 93, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zu, Y. A highlight of recent advances in aptamer technology and its application. Molecules 2015, 20, 11959–11980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashmakova, E.E.; Krasitskaya, V.V.; Zamay, G.S.; Zamay, T.N.; Frank, L.A. Bioluminescent aptamer-based solid-phase microassay to detect lung tumor cells in plasma. Talanta 2019, 199, 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobjeva, M.A.; Krasitskaya, V.V.; Fokina, A.A.; Timoshenko, V.V.; Nevinsky, G.A.; Venyaminova, A.G.; Frank, L.A. RNA aptamer against autoantibodies associated with multiple sclerosis and bioluminescent detection probe on its basis. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 2590–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasitskaya, V.V.; Chaukina, V.V.; Abroskina, M.V.; Vorobyeva, M.A.; Ilminskaya, A.A.; Prokopenko, S.V.; Nevinsky, G.A.; Venyaminova, A.G.; Frank, L.A. Bioluminescent aptamer-based sandwich-type assay of anti-myelin basic protein autoantibodies associated with multiple sclerosis. Anal. Chim. Acta 2019, 1064, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasitskaya, V.V.; Goncharova, N.S.; Biriukov, V.V.; Bashmakova, E.E.; Kabilov, M.R.; Baykov, I.K.; Sokolov, A.E.; Frank, L.A. The Ca2+-regulated photoprotein obelin as a tool for SELEX monitoring and DNA aptamer affinity evaluation. Photochem. Photobiol. 2020, 96, 1041–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydova, A.; Vorobyeva, M.; Bashmakova, E.; Vorobjev, P.; Krasheninina, O.; Tupikin, A.; Kabilov, M.; Krasitskaya, V.; Frank, L.; Venyaminova, A. Development and characterization of novel 2′-F-RNA aptamers specific to human total and glycated hemoglobins. Anal. Biochem. 2019, 570, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasitskaya, V.V.; Davydova, A.S.; Vorobyeva, M.A.; Frank, L.A. The Ca2+-regulated photoprotein obelin as a target for the RNA aptamer selection. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2018, 44, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydova, A.S.; Krasitskaya, V.V.; Vorobjev, P.E.; Krasheninina, O.A.; Tupikin, A.E.; Kabilov, M.R.; Frank, L.A.; Venyaminova, A.G.; Vorobyeva, M.A. RNA aptamer to photoprotein obelin: A reporter-recruiting module for novel bioluminescent aptasensing systems. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 32393–32399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inouye, S.; Sato, J.; Sasaki, S.; Sahara, Y. Streptavidin-aequorin fusion protein for bioluminescent immunoassay. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2011, 75, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashmakova, E.E.; Krasitskaya, V.V.; Kudryavtsev, A.N.; Grigorenko, V.G.; Frank, L.A. Hybrid minimal core streptavidin-obelin as a versatile reporter for bioluminescence-based bioassay. Photochem. Photobiol. 2017, 93, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inouye, S.; Sahara-Miura, Y. A fusion protein of the synthetic IgG-binding domain and aequorin: Expression and purification from E. coli cells and its application. Protein Expr. Purif. 2017, 137, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasitskaya, V.V.; Bashmakova, E.E.; Kudryavtsev, A.N.; Vorobjeva, M.A.; Shatunova, E.A.; Frank, L.A. Hybrid protein ZZ-OL as an analytical tool for biotechnology research. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 45. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Markova, S.V.; Vysotski, E.S.; Blinks, J.R.; Burakova, L.P.; Wang, B.C.; Lee, J. Obelin from the bioluminescent marine hydroid Obelia geniculata: Cloning, expression, and comparison of some properties with those of other Ca2+-regulated photoproteins. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 2227–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eremeeva, E.V.; Burakova, L.P.; Krasitskaya, V.V.; Kudryavtsev, A.N.; Shimomura, O.; Frank, L.A. Hydrogen-bond network between C-terminus and Arg from the first α-helix stabilizes a photoprotein molecule. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2014, 13, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamorsky, K.T.; Ensor, C.M.; Wei, Y.; Daunert, S. A bioluminescent molecular switch for glucose. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2008, 47, 3718–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Hamorsky, K.T.; Ensor, C.M.; Anderson, K.W.; Daunert, S. Cyclic AMP receptor protein-aequorin molecular switch for cyclic AMP. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011, 22, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hamorsky, K.T.; Ensor, C.M.; Pasini, P.; Daunert, S. A protein switch sensing system for the quantification of sulfate. Anal. Biochem. 2012, 421, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Hamorsky, K.T.; Ensor, C.M.; Dikici, E.; Pasini, P.; Bachas, L.; Daunert, S. Bioluminescence inhibition assay for the detection of hydroxylated polychlorinated biphenyls. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 7648–7655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmani, H.; Sajedi, R.H. Aequorin as a sensitive and selective reporter for detection of dopamine: A photoprotein inhibition assay approach. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 122, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmani, H.; Ghavamipour, F.; Sajedi, R.H. Bioluminescence detection of superoxide anion using aequorin. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 12768–12774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunstan, S.L.; Sala-Newby, G.B.; Fajardo, A.B.; Taylor, K.M.; Campbell, A.K. Cloning and expression of the bioluminescent photoprotein pholasin from the bivalve mollusc Pholas dactylus. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 9403–9409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourooz-Zadeh, J.; Ziegler, D.; Sohr, C.; Betteridge, J.D.; Knight, J.; Hothersall, J. The use of pholasin as a probe for the determination of plasma total antioxidant capacity. Clin. Biochem. 2006, 39, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, N.; Ashwin, H.; Smart, N.; Bayon, Y.; Scarborough, N.; Hunt, N. The innate oxygen dependent immune pathway as a sensitive parameter to predict the performance of biological graft materials. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 6380–6392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, N.; Ahswin, H.; Smart, N.J.; Bayon, Y.; Hunt, J.A. In vitro activation of human leukocytes in response to contact with synthetic hernia meshes. Clin. Biochem. 2012, 45, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.A.; Fok, M.; Bryan, N. Impact of cell purification technique of autologous human adult stem cells on inflammatory reaction. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 7626–7631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Passacquale, G.; Gkaliagkousi, E.; Ritter, J.; Ferro, A. Platelet nitric oxide signalling in heart failure: Role of oxidative stress. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011, 91, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farthing, D.E.; Sica, D.; Hindle, M.; Edinboro, L.; Xi, L.; Gehr, T.W.B.; Gehr, L.; Farthing, C.A.; Larus, T.L.; Fakhrya, I.; et al. A rapid and simple chemiluminescence method for screening levels of inosine and hypoxanthine in non-traumatic chest pain patients. Luminescence 2011, 26, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, D.L.; Richards, R.S.; Lexis, L.A. Using chemiluminescence to determine whole blood antioxidant capacity in rheumatoid arthritis and Parkinson’s disease patients. Luminescence 2018, 33, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenz, W.W.; McCann, R.O.; Longiaru, M.; Cormierm, M.J. Isolation and expression of a cDNA encoding Renilla reniformis luciferase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 4438–4442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markova, S.V.; Larionova, M.D.; Burakova, L.P.; Vysotski, E.S. The smallest natural high-active luciferase: Cloning and characterization of novel 16.5-kDa luciferase from copepod Metridia longa. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 457, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasitskaya, V.V.; Burakova, L.P.; Pyshnaya, I.A.; Frank, L.A. Bioluminescent reporters for identification of gene allelic variants. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2012, 38, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutsiopoulou, A.; Hunt, E.; Broyles, D.; Pereira, C.A.; Woodward, K.; Dikici, E.; Kaifer, A.; Daunert, S.; Deo, S.K. Bioorthogonal protein conjugation: Application to the development of a highly sensitive bioluminescent immunoassay for the detection of interferon-γ. Bioconjugate Chem. 2017, 28, 1749–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouters, S.F.A.; Vugs, W.J.P.; Arts, R.; de Leeuw, N.M.; Teeuwen, R.W.H.; Merkx, M. Bioluminescent antibodies through photoconjugation of protein G-luciferase fusion proteins. Bioconjugate Chem. 2020, 31, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loening, A.M.; Fenn, T.D.; Wu, A.M.; Gambhir, S.S. Consensus guided mutagenesis of Renilla luciferase yields enhanced stability and light output. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2006, 19, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burakova, L.P.; Kudryavtsev, A.N.; Stepanyuk, G.A.; Baykov, I.K.; Morozova, V.V.; Tikunova, N.V.; Dubova, M.A.; Lyapustin, V.N.; Yakimenko, V.V.; Frank, L.A. Bioluminescent detection probe for tick-borne encephalitis virus immunoassay. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 5417–5423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Grotzke, J.E.; Cresswell, P. A novel probe to assess cytosolic entry of exogenous proteins. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varnosfaderani, Z.G.; Emamzadeh, R.; Nazari, M.; Zarean, M. Detection of a prostate cancer cell line using a bioluminescent affiprobe: An attempt to develop a new molecular probe for ex vivo studies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 138, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.A.; Yoon, H.S.; Park, S.H.; Kim, D.Y.; Pyo, A.; Kim, H.S.; Min, J.J.; Hong, Y. Engineering of monobody conjugates for human EphA2-specific optical imaging. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burbelo, P.D.; Lebovitz, E.E.; Notkins, A.L. Luciferase immunoprecipitation systems for measuring antibodies in autoimmune and infectious diseases. Transl. Res. 2015, 165, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tin, C.M.; Yuan, L.; Dexter, R.J.; Parra, G.I.; Bui, T.; Green, K.Y.; Sosnovtsev, S.V. A luciferase immunoprecipitation system (LIPS) assay for profiling human norovirus antibodies. J. Virol. Methods 2017, 248, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, T.; Jäättelä, M. Renilla luciferase-LC3 based reporter assay for measuring autophagic flux. Methods Enzymol. 2017, 588, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, T.; Dau, P.; Duffort, S.; Daftarian, P.; Joshi, P.M.; Vazquez-Padron, R.; Deo, S.K.; Daunert, S. An enhanced bioluminescence-based Annexin V probe for apoptosis detection in vitro and in vivo. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzannia, A.; Roghanian, R.; Zarkesh-Esfahani, S.H.; Nazari, M.; Emamzadeh, R. FcUni-RLuc: An engineered Renilla luciferase with Fc binding ability and light emission activity. Analyst 2015, 140, 1438–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, M.; Emamzadeh, R.; Hosseinkhani, S.; Cevenini, L.; Michelini, E.; Roda, A. Renilla luciferase-labeled Annexin V: A new probe for detection of apoptotic cells. Analyst 2012, 137, 5062–5070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionova, M.D.; Markova, S.V.; Tikunova, N.V.; Vysotski, E.S. The smallest isoform of Metridia longa luciferase as a fusion partner for hybrid proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leo, T.C.; Santos, S.N.D.; Andrade, C.D.C.; Ricci, E.; Turato, W.M.; Lopes, N.P.; Oliveira, R.S.; Bernardes, E.S.; Dias-Baruffi, M. Engineering of galectin-3 for glycan-binding optical imaging. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 521, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weihs, F.; Peh, A.; Dacres, H. A red-shifted bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) biosensing system for rapid measurement of plasmin activity in human plasma. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1102, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, H.; Chen, X.; Wei, A.; Song, X.; Wang, W.; Liang, L.; Zhao, Q.; Han, Z.; Han, Z.; Wang, X.; et al. Comparison of teratoma formation between embryonic stem cells and parthenogenetic embryonic stem cells by molecular imaging. Stem. Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 7906531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saw, W.T.; Matsuda, Z.; Eisenberg, R.J.; Cohen, G.H.; Atanasiu, D. Using a split luciferase assay (SLA) to measure the kinetics of cell-cell fusion mediated by herpes simplex virus glycoproteins. Methods 2015, 90, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakane, S.; Matsuda, Z. Dual split protein (DSP) assay to monitor cell-cell membrane fusion. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1313, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Matsuyama, S.; Li, X.; Takeda, M.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Inoue, J.-I.; Matsuda, Z. Identification of nafamostat as a potent inhibitor of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus S protein-mediated membrane fusion using the split-protein-based cell-cell fusion assay. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 6532–6539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkenazi, S.; Plotnikov, A.; Bahat, A.; Dikstein, R. Effective cell-free drug screening protocol for protein-protein interaction. Anal. Biochem. 2017, 532, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toribio, V.; Morales, S.; López-Martín, S.; Cardeñes, B.; Cabañas, C.; Yáñez-Mó, M. Development of a quantitative method to measure EV uptake. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, C.H.; Bromley, J.R.; Stenbæk, A.; Rasmussen, R.E.; Scheller, H.V.; Sakuragi, Y. A reversible Renilla luciferase protein complementation assay for rapid identification of protein-protein interactions reveals the existence of an interaction network involved in xyloglucan biosynthesis in the plant Golgi apparatus. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, W.; Long, C.; Zhou, H.; Wang, H.; Sun, X. The split Renilla luciferase complementation assay is useful for identifying the interaction of Epstein-Barr virus protein kinase BGLF4 and a heat shock protein Hsp90. Acta Virol. 2016, 60, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varnum, M.M.; Clayton, K.A.; Yoshii-Kitahara, A.; Yonemoto, G.; Koro, L.; Ikezu, S.; Ikezu, T. A split-luciferase complementation, real-time reporting assay enables monitoring of the disease-associated transmembrane protein TREM2 in live cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 10651–10663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, F.A.; Parkkola, H.; Manoharan, G.B.; Abankwa, D. Medium-throughput detection of Hsp90/Cdc37 protein-protein interaction inhibitors using a split Renilla luciferase-based assay. SLAS Discov. 2020, 25, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, W.; Li, D.; Chen, L.; Xia, H.; Tang, Q.; Chen, B.; Gong, Q.; Gao, F.; Bi, F. Novel Bioluminescent Activatable Reporter for Src Tyrosine Kinase Activity in Living Mice. Theranostics 2016, 6, 594–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.B.; Ozawa, T.; Umezawa, Y. A genetically encoded bioluminescent indicator for illuminating proinflammatory cytokines. MethodsX 2016, 3, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Hisaoka, M.; Nagata, K.; Okuwaki, M. Functional characterization and efficient detection of Nucleophosmin/NPM1 oligomers. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 480, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulmurugan, R.; Afjei, R.; Sekar, T.V.; Babikir, H.A.; Massoud, T.F. A protein folding molecular imaging biosensor monitors the effects of drugs that restore mutant p53 structure and its downstream function in glioblastoma cells. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 21495–21511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kobayashi, H.; Picard, L.P.; Schönegge, A.M.; Bouvier, M. Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer-based imaging of protein-protein interactions in living cells. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 1084–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimri, S.; Basu, S.; De, A. Use of BRET to study protein-protein interactions in vitro and in vivo. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1443, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strungs, E.G.; Luttrell, L.M.; Lee, M.H. Probing arrestin function using intramolecular FlAsH-BRET biosensors. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1957, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuboi, S.; Jin, T. Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) coupled near-infrared imaging of apoptotic cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020, 2081, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpf, C.; Wimmer, T.; Lorenz, B.; Stieger, K. Creation of different bioluminescence resonance energy transfer based biosensors with high affinity to VEGF. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacres, H.; Michie, M.; Wang, J.; Pfleger, K.D.; Trowell, S.C. Effect of enhanced Renilla luciferase and fluorescent protein variants on the Förster distance of bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 425, 625–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathod, M.; Mal, A.; De, A. Reporter-based BRET sensors for measuring biological functions in vivo. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1790, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samanta, A.; Medintz, I.L. Bioluminescence-based energy transfer using semiconductor quantum dots as acceptors. Sensors 2020, 20, 2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Zhang, J. Self-illumination of carbon dots by bioluminescence resonance energy transfer. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, A.K.; Baier, L.J. Using luciferase reporter assays to identify functional variants at disease-associated loci. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1706, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, H.M.; Kang, M.K.; Sohn, D.H.; Han, S.J. 5′-UTR and ORF elements, as well as the 3′-UTR regulate the translation of Cyclin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 527, 968–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, L.; Hu, D.; Ge, X.; Guo, X.; Yang, H. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus suppresses post-transcriptionally the protein expression of IFN-β by upregulating cellular microRNAs in porcine alveolar macrophages in vitro. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 15, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Ye, G.; Deng, F.; Wang, G.; Cui, M.; Fang, L.; Xiao, S.; Fu, Z.F.; Peng, G. Structural basis for the inhibition of host gene expression by porcine epidemic diarrhea virus nsp1. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e01896-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguchi, T.; Kubota, S.; Takigawa, M. Promoter analyses of CCN genes. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1489, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palavecino, C.E.; Carrasco-Véliz, N.; Quest, A.F.G.; Garrido, M.P.; Valenzuela-Valderrama, M. The 5′ untranslated region of the anti-apoptotic protein Survivin contains an inhibitory upstream AUG codon. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 526, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Tang, M.; Zou, L.; Su, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Li, L.; et al. Quantitative evaluation of the transcriptional activity of steroid hormone receptor mutants and variants using a single vector with two reporters and a receptor expression cassette. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, P.P.; Flores Avile, C.; Jewett, M.W. A dual luciferase reporter system for B. burgdorferi measures transcriptional activity during tick-pathogen interactions. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inan, C.; Muratoglu, H.; Arif, B.M.; Demirbag, Z. Transcriptional analysis of the putative glycosyltransferase gene (amv248) of the Amsacta moorei entomopoxvirus. Virus. Res. 2018, 243, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unal, H. Luciferase reporter assay for unlocking ligand-mediated signaling of GPCRs. Methods Cell Biol. 2019, 149, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Shi, X.; Xie, J.; Mao, W.; Tian, J.; Wang, F. Real-time functional bioimaging of neuron-specific microRNA dynamics during neuronal differentiation using a dual luciferase reporter. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 1696–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, C.Y.; Tsai, Y.S.; Chou, W.W.; Liu, T.; Huang, C.F.; Wang, S.C.; Tsai, P.C.; Yeh, M.L.; Hsieh, M.Y.; Huang, C.I.; et al. The IL-6/STAT3 pathway upregulates microRNA-125b expression in hepatitis C virus infection. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 11291–11302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J. MiR-182 promotes glucose metabolism by upregulating hypoxia-inducible factor 1α in NSCLC cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 504, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Xie, J.; Tian, J.; Wang, F. Intron retained bioluminescence reporter for real-time imaging of pre-mRNA splicing in living subjects. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 12392–12398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salani, M.; Urbina, F.; Brenner, A.; Morini, E.; Shetty, R.; Gallagher, C.S.; Law, E.A.; Sunshine, S.; Finneran, D.J.; Johnson, G.; et al. Development of a screening platform to identify small molecules that modify ELP1 pre-mRNA splicing in familial dysautonomia. SLAS Discov. 2019, 24, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Ni, Y.Y.; Walker, M.; Huang, Y.W.; Meng, X.J. Roles of the genomic sequence surrounding the stem-loop structure in the junction region including the 3′ terminus of open reading frame 1 in hepatitis E virus replication. J. Med. Virol. 2018, 90, 1524–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; He, Y.; Zhang, R.; Liu, P.; Yang, C.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, M.; Jia, R.; Zhu, D.; et al. Establishment of a reverse genetics system for duck Tembusu virus to study virulence and screen antiviral genes. Antiviral. Res. 2018, 157, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, D.; Ni, Y.Y.; Meng, X.J. Substitution of amino acid residue V1213 in the helicase domain of the genotype 3 hepatitis E virus reduces virus replication. Virol. J. 2018, 15, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, W.; Silvers, R.; Ouellette, M.; Wu, Z.; Lu, Q.; Li, H.; Gallagher, K.; Johnson, K.; Montoute, M. A luciferase reporter gene system for high-throughput screening of γ-globin gene activators. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1439, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.; Lu, W.; Ma, Y.; Guo, W.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Wu, J.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, X. A novel dual-luciferase assay for anti-HIV drug screening based on the CCR5/CXCR4 promoters. J. Virol. Methods 2018, 256, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Y.; Li, Y.; Jasperson, D.; Henningson, J.; Lee, J.; Ma, J.; Li, Y.; Duff, M.; Liu, H.; Bai, D.; et al. Identification and evaluation of antivirals for Rift Valley fever virus. Vet. Microbiol. 2019, 230, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Niu, J.; Wang, C.; Huang, B.; Wang, W.; Zhu, N.; Deng, Y.; Wang, H.; Ye, F.; Cen, S.; et al. High-throughput screening and identification of potent broad-spectrum inhibitors of coronaviruses. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00023-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, C.; Wang, R.; Chen, S.; Li, Z. Dual bioluminescence imaging of tumor progression and angiogenesis. J. Vis. Exp. 2019, 150, e59763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangadaran, P.; Ahn, B.C. In vivo tracking of tumor-derived bioluminescent extracellular vesicles in mice. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020, 2081, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Shen, L.; Huang, B.; Ye, F.; Zhao, L.; Wang, H.; Deng, Y.; Tan, W. Non-invasive bioluminescence imaging of HCoV-OC43 infection and therapy in the central nervous system of live mice. Antiviral. Res. 2020, 173, 104646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, L.; Matz, E.L.; Gu, X.; Shu, F.; Paxton, J.; Song, J.; Yoo, J.; Atala, A.; Jackson, J.; Zhang, Y. Non-invasive cell tracking with brighter and red-transferred luciferase for potential application in stem cell therapy. Cell Transplant. 2019, 28, 1542–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Lu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xu, E.; Ho, A.; Singh, P.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Yang, F.; Tietjen, G.T.; et al. Quantitating endosomal escape of a library of polymers for mRNA delivery. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 1117–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markova, S.V.; Larionova, M.D.; Vysotski, E.S. Shining light on the secreted luciferases of marine copepods: Current knowledge and applications. Photochem. Photobiol. 2019, 95, 705–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- England, C.G.; Ehlerding, E.B.; Cai, W. NanoLuc: A small luciferase is brightening up the field of bioluminescence. Bioconjugate Chem. 2016, 27, 1175–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soave, M.; Heukers, R.; Kellam, B.; Woolard, J.; Smit, M.J.; Briddon, S.J.; Hill1, S.J. Monitoring allosteric interactions with CXCR4 using NanoBiT conjugated nanobodies. Cell Chem. Biol. 2020, 27, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soave, M.; Kellam, B.; Woolard, J.; Briddon, S.J.; Hill, S.J. NanoBiT Complementation to monitor agonist-induced adenosine A1 receptor internalization. SLAS Discov. 2020, 25, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooley, R.; Kara, N.; Hui, N.S.; Tart, J.; Roustan, C.; George, R.; Hancock, D.C.; Binkowski, B.F.; Wood, K.V.; Ismail, M. Development of a cell-free split-luciferase biochemical assay as a tool for screening for inhibitors of challenging protein-protein interaction targets. Wellcome Open Res. 2020, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Boulch, M.; Brossard, A.; Le Dez, G.; Leon, S.; Rabut, G. Sensitive detection of protein ubiquitylation using a protein fragment complementation assay. J. Cell Sci. 2020, 133, jcs240093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, K.; Azad, T.; Ling, M.; Janse van Rensburg, H.J.; Pipchuk, A.; Shen, H.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, X. Identification of celastrol as a novel YAP-TEAD inhibitor for cancer therapy by high throughput screening with ultrasensitive YAP/TAZ-TEAD biosensors. Cancers 2019, 11, 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machleidt, T.; Woodroofe, C.C.; Schwinn, M.K.; Méndez, J.; Robers, M.B.; Zimmerman, K.; Otto, P.; Daniels, D.L.; Kirkland, T.A.; Wood, K.V. NanoBRET—A novel BRET platform for the analysis of protein–protein interactions. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 1797–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, X.L.; Luo, Y.; Ivanov, A.A.; Su, R.; Havel, J.J.; Li, Z.; Khuri, F.R.; Du, Y.; Fu, H. Enabling systematic interrogation of protein–protein interactions in live cells with a versatile ultra-high-throughput biosensor platform. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 8, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boursier, M.E.; Levin, S.; Zimmerman, K.; Machleidt, T.; Hurst, R.; Butler, B.L.; Eggers, C.T.; Kirkland, T.A.; Wood, K.V.; Friedman Ohana, R. The luminescent HiBiT peptide enables selective quantitation of G protein-coupled receptor ligand engagement and internalization in living cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 5124–5135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillipou, A.N.; Lay, C.S.; Carver, C.E.; Messenger, C.; Evans, J.P.; Lewis, A.J.; Gordon, L.J.; Mahmood, M.; Greenhough, L.A.; Sammon, D.; et al. Cellular target engagement approaches to monitor epigenetic reader domain interactions. SLAS Discov. 2020, 25, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.H.; Shao, X.X.; Hu, M.J.; Wei, D.; Liu, Y.L.; Xu, Z.G.; Guo, Z.Y. A novel BRET-based binding assay for interaction studies of relaxin family peptide receptor 3 with its ligands. Amino Acids 2017, 49, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oishi, A.; Dam, J.; Jockers, R. β-Arrestin-2 BRET biosensors detect different β-Arrestin-2 conformations in interaction with GPCRs. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hamer, A.; Dierickx, P.; Arts, R.; de Vries, J.S.P.M.; Brunsveld, L.; Merkx, M. Bright bioluminescent BRET sensor proteins for measuring intracellular Caspase activity. ACS Sens. 2017, 2, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.H.; French, A.R.; Trull, K.J.; Tat, K.; Varney, S.A.; Tantama, M. Ratiometric BRET measurements of ATP with a genetically-encoded luminescent sensor. Sensors 2019, 19, 3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoare, B.L.; Kocan, M.; Bruell, S.; Scott, D.J.; Bathgate, R.A.D. Using the novel HiBiT tag to label cell surface relaxin receptors for BRET proximity analysis. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2019, 7, e00513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimri, S.; Arora, R.; Jasani, A.; De, A. Dynamic monitoring of STAT3 activation in live cells using a novel STAT3 phospho-BRET sensor. Am. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2019, 9, 321334. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddart, L.A.; Vernall, A.J.; Bouzo-Lorenzo, M.; Bosma, R.; Kooistra, A.J.; de Graaf, C.; Vischer, H.F.; Leurs, R.; Briddon, S.J.; Kellam, B.; et al. Development of novel fluorescent histamine H 1-receptor antagonists to study ligand-binding kinetics in living cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiblot, J.; Yu, Q.; Sabbadini, M.D.; Reymond, L.; Xue, L.; Schena, A.; Sallin, O.; Hill, N.; Griss, R.; Johnsson, K. Luciferases with tunable emission wavelengths. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 129, 14748–14752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpatrick, L.E.; Friedman-Ohana, R.; Alcobia, D.C.; Riching, K.; Peach, C.J.; Wheal, A.J.; Briddon, S.J.; Robers, M.B.; Zimmerman, K.; Machleidt, T.; et al. Real-time analysis of the binding of fluorescent VEGF165a to VEGFR2 in living cells: Effect of receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors and fate of internalized agonist-receptor complexes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 136, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christiansen, E.; Hudson, B.D.; Hansen, A.H.; Milligan, G.; Ulven, T. Development and characterization of a potent free fatty acid receptor 1 (FFA1) fluorescent tracer. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 4849–4858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thirukkumaran, O.M.; Wang, C.; Asouzu, N.J.; Fron, E.; Rocha, S.; Hofkens, J.; Lavis, L.D.; Mizuno, H. Improved HaloTag ligand enables BRET imaging with NanoLuc. Front. Chem. 2020, 7, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Los, G.V.; Encell, L.P.; McDougall, M.G.; Hartzell, D.D.; Karassina, N.; Zimprich, C.; Wood, M.G.; Learish, R.; Ohana, R.F.; Urh, M.; et al. HaloTag: A novel protein labeling technology for cell imaging and protein analysis. ACS Chem. Biol. 2008, 3, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoddart, L.A.; Kilpatrick, L.E.; Hill, S.J. NanoBRET approaches to study ligand binding to GPCRs and RTKs. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 39, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dale, N.C.; Johnstone, E.K.M.; White, C.W.; Pfleger, K.D.G. NanoBRET: The bright future of proximity-based assays. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, I.S.; Seo, H.R.; Kim, K.; Lee, H.; Shum, D.; Choi, I.; Kim, J. Identification of inhibitors of Bcl-2 family protein-protein interaction by combining the BRET screening platform with virtual screening. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 527, 709715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocking, T.A.M.; Buzink, M.C.M.L.; Leurs, R.; Vischer, H.F. Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer based G protein-activation assay to probe duration of antagonism at the histamine H3 receptor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpatrick, L.E.; Alcobia, D.C.; White, C.W.; Peach, C.J.; Glenn, J.R.; Zimmerman, K.; Kondrashov, A.; Pfleger, K.D.G.; Ohana, R.F.; Robers, M.B.; et al. Complex formation between VEGFR2 and the β2-Adrenoceptor. Cell Chem. Biol. 2019, 26, 830–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanznaster, D.; Massari, C.M.; Marková, V.; Šimková, T.; Duroux, R.; Jacobson, K.A.; Fernández-Dueñas, V.; Tasca, C.I.; Ciruela, F. Adenosine A1-A2A receptor-receptor interaction: Contribution to guanosine-mediated effects. Cells 2019, 8, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman Ohana, R.; Hurst, R.; Rosenblatt, M.; Levin, S.; Machleidt, T.; Kirkland, T.A.; Encell, L.P.; Robers, M.B.; Wood, K.V. Utilizing a simple method for stoichiometric protein labeling to quantify antibody blockade. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, T.T.; Ang, Z.; Verma, R.; Koean, R.; Kit Chung Tam, J.; Ling Ding, J. pHLuc, a ratiometric luminescent reporter for in vivo monitoring of tumor acidosis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, A.; Sharkey, J.; Plagge, A.; Wilm, B.; Murray, P. Multicolour in vivo bioluminescence imaging using a NanoLuc-based BRET reporter in combination with firefly luciferase. Contrast Media. Mol. Imaging 2018, 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamkaew, A.; Sun, H.; England, C.G.; Cheng, L.; Liu, Z.; Cai, W. Quantum dot-NanoLuc bioluminescence resonance energy transfer enables tumor imaging and lymph node mapping in vivo. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 6997–7000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhmin, A.; Hall, M.P.; Machleidt, T.; Walker, J.R.; Wood, K.V.; Kirkland, T.A. Coelenterazine analogues emit red-shifted bioluminescence with NanoLuc. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 8559–8567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, H.W.; Karmach, O.; Ji, A.; Carter, D.; Martins-Green, M.M.; Ai, H.W. Red-shifted luciferase-luciferin pairs for enhanced bioluminescence imaging. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 971–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishihara, R.; Hoshino, E.; Kakudate, Y.; Kishigami, S.; Iwasawa, N.; Sasaki, S.I.; Nakajima, T.; Sato, M.; Nishiyama, S.; Citterio, D.; et al. Azide- and Dye-conjugated coelenterazine analogues for a multiplex molecular imaging platform. Bioconjugate Chem. 2018, 29, 1922–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Cumberbatch, D.; Centanni, S.; Shi, S.Q.; Winder, D.; Webb, D.; Johnson, C.H. Coupling optogenetic stimulation with NanoLuc-based luminescence (BRET) Ca2+ sensing. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Rancic, V.; Wu, J.; Ballanyi, K.; Campbell, R.E. A Bioluminescent Ca2+ indicator based on a topological variant of GCaMP6s. ChemBioChem 2019, 20, 516–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, R.; Aper, S.J.A.; Merkx, M. Engineering BRET-sensor proteins. Methods Enzymol. 2017, 589, 87–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, R.; Ludwig, S.K.J.; van Gerven, B.C.B.; Estirado, E.M.; Milroy, L.G.; Merkx, M. Semisynthetic bioluminescent sensor proteins for direct detection of antibodies and small molecules in solution. ACS Sens. 2017, 2, 1730–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenda, K.; van Gerven, B.; Arts, R.; Hiruta, Y.; Merkx, M.; Citterio, D. Paper-based antibody detection devices using bioluminescent BRET-switching sensor proteins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2018, 57, 15369–15373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arts, R.; den Hartog, I.; Zijlema, S.E.; Thijssen, V.; van der Beelen, S.H.E.; Merkx, M. Detection of antibodies in blood plasma using bioluminescent sensor proteins and a smartphone. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 4525–4532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, L.; Yu, Q.; Griss, R.; Schena, A.; Johnsson, K. Bioluminescent antibodies for point-of-care diagnostics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017, 56, 7112–7116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, W.; van de Wiel, K.M.; Meijer, L.H.H.; Saha, B.; Merkx, M. Nucleic acid detection using BRET-beacons based on bioluminescent protein-DNA hybrids. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 2862–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigeto, H.; Ikeda, T.; Kuroda, A.; Funabashi, H. A BRET-based homogeneous insulin assay using interacting domains in the primary binding site of the insulin receptor. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 2764–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Li, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wan, D.; Barnych, B.; Li, Y.; Tu, Z.; He, Q.; Fu, J.; Hammock, B.D. One-Step ultrasensitive bioluminescent enzyme immunoassay based on Nanobody/Nanoluciferase fusion for detection of aflatoxin B1 in cereal. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 5221–5229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cai, Q.; Liang, Y.; Shui, J.; Tang, S. A simple and high-throughput luciferase immunosorbent assay for both qualitative and semi-quantitative detection of anti-HIV-1 antibodies. Virus Res. 2019, 263, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tin, C.M.; Sosnovtsev, S.V. Detection of human norovirus-specific antibodies using the luciferase immunoprecipitation system (LIPS). Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 2024, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Jiang, P.; Li, N.; Yan, Q.; Wang, X. A luciferase immunoprecipitation assay for the detection of proinsulin/insulin autoantibodies. Clin. Biochem. 2018, 54, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, J.Z.; Tamsen, S.; Song, Y.; Tsourkas, A. LASIC: Light activated site-specific conjugation of native IgGs. Bioconjugate Chem. 2015, 26, 1456–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, Y.; Mashimo, Y.; Mie, M.; Kobatake, E. Design of luciferase-displaying protein nanoparticles for use as highly sensitive immunoassay detection probes. Analyst 2016, 141, 6557–6563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mie, M.; Niimi, T.; Mashimo, Y.; Kobatake, E. Construction of DNA-NanoLuc luciferase conjugates for DNA aptamer-based sandwich assay using Rep protein. Biotechnol. Lett. 2019, 41, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinkley, T.C.; Garing, S.; Singh, S.; Le Ny, A.M.; Nichols, K.P.; Peters, J.E.; Talbert, J.N.; Nugen, S.R. Reporter bacteriophage T7 NLC utilizes a novel NanoLuc: CBM fusion for the ultrasensitive detection of Escherichia coli in water. Analyst 2018, 143, 4074–4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozak, S.; Alcaine, S.D. Phage-based forensic tool for spatial visualization of bacterial contaminants in cheese. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 5964–5971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohmuro-Matsuyama, Y.; Chung, C.I.; Ueda, H. Demonstration of protein-fragment complementation assay using purified firefly luciferase fragments. BMC Biotechnol. 2013, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmuro-Matsuyama, Y.; Ueda, H. Homogeneous noncompetitive luminescent immunodetection of small molecules by ternary protein fragment complementation. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 3001–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranawakage, D.C.; Takada, T.; Kamachi, Y. HiBiT-qIP, HiBiT-based quantitative immunoprecipitation, facilitates the determination of antibody affinity under immunoprecipitation conditions. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetsuo, M.; Matsuno, K.; Tamura, T.; Fukuhara, T.; Kim, T.; Okamatsu, M.; Tautz, N.; Matsuura, Y.; Sakoda, Y. Development of a high-throughput serum neutralization test using recombinant pestiviruses possessing a small reporter tag. Pathogens 2020, 9, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.; Moser, L.A.; Poole, D.S.; Mehle, A. Highly sensitive real-time in vivo imaging of an influenza reporter virus reveals dynamics of replication and spread. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 13321–13329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, E.A.; Meliopoulos, V.A.; Savage, C.; Livingston, B.; Mehle, A.; Schultz-Cherry, S. Visualizing real-time influenza virus infection, transmission and protection in ferrets. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Liu, M.; Russell, C.J. Directed evolution of an influenza reporter virus to restore replication and virulence and enhance non-invasive bioluminescence imaging in mice. J. Virol. 2018, e00593-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiem, K.; Rangel-Moreno, J.; Nogales, A.; Martinez-Sobrido, L. A Luciferase-fluorescent reporter influenza virus for live imaging and quantification of viral infection. J. Vis. Exp. 2019, 150, e59890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogales, A.; Ávila-Pérez, G.; Rangel-Moreno, J.; Chiem, K.; DeDiego, M.L.; Martínez-Sobrido, L. A novel fluorescent and bioluminescent Bireporter influenza A virus to evaluate viral infections. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00032-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishitsuji, H.; Harada, K.; Ujino, S.; Zhang, J.; Kohara, M.; Sugiyama, M.; Mizokami, M.; Shimotohno, K. Investigating the hepatitis B virus life cycle using engineered reporter hepatitis B viruses. Cancer Sci. 2018, 109, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, K.; Nishitsuji, H.; Ujino, S.; Shimotohno, K. Identification of KX2-391 as an inhibitor of HBV transcription by a recombinant HBV-based screening assay. Antiviral Res. 2017, 144, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.; Ping, C.Y.; Sun, S.; Cheng, X.; Han, P.Y.; Zhang, Y.G.; Sun, D.X. Construction of a replication-competent hepatitis B virus vector carrying secreted luciferase transgene and establishment of new hepatitis B virus replication and expression cell lines. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 5961–5972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkolnicka, D.; Pollán, A.; da Silva, N.; Oechslin, N.; Gouttenoire, J.; Moradpour, D. Recombinant Hepatitis E Viruses harboring tags in the ORF1 protein. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00459-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirui, J.; Freed, E.O. Generation and validation of a highly sensitive bioluminescent HIV1 reporter vector that simplifies measurement of virus release. Retrovirology 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, Y.; Kawagishi, T.; Nouda, R.; Onishi, M.; Pannacha, P.; Nurdin, J.A.; Nomura, K.; Matsuura, Y.; Kobayashia, T. Development of 1 stable rotavirus reporter expression systems. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e01774-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michihito, S.; Anindita, P.D.; Wallaya, P.; Michael, C.; Kobayashi, S.; Yasuko, O.; Hirofumi, S. Development of a rapid and quantitative method for the analysis of viral entry and release using a NanoLuc luciferase complementation assay. Virus Res. 2018, 243, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, T.; Igarashi, M.; Enkhbold, B.; Suzuki, T.; Okamatsu, M.; Ono, C.; Mori, H.; Izumi, T.; Sato, A.; Fauzyah, Y.; et al. In vivo dynamics of reporter Flaviviridae viruses. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e01191-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, S.I.; Song, B.H.; Woolley, M.E.; Frank, J.C.; Julander, J.G.; Lee, Y.M. Development, characterization, and application of two reporter-expressing recombinant Zika viruses. Viruses 2020, 12, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belarbi, E.; Legros, V.; Basset, J.; Despres, P.; Roques, P.; Choumet, V. Bioluminescent ross river virus allows live monitoring of acute and long-term alphaviral infection by in vivo imaging. Viruses 2019, 11, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh-hashi, K.; Furuta, E.; Norisada, J.; Amaya, F.; Hirata, Y.; Kiuchi, K. Application of NanoLuc to monitor the intrinsic promoter activity of GRP78 using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Genes Cells 2016, 21, 1137–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, S.; Adams, L.; Guhathakurta, S.; Kim, Y.S. A novel tool for monitoring endogenous alpha-synuclein transcription by NanoLuciferase tag insertion at the 3′end using CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing technique. Sci. Rep. 2017, 8, 45883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, D.H.; Carré, A.; Guzzardo, P.M.; Banning, C.; Mangena, R.; Henley, T.; Oberndorfer, S.; Gapp, B.V.; Nijman, S.M.B.; Brummelkamp, T.R.; et al. A generic strategy for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene tagging. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.A.; Richie, C.T.; Zhang, Y.; Heathward, E.J.; Coke, L.M.; Park, E.Y.; Harvey, B.K. In vitro modeling of HIV proviral activity in microglia. FEBS J. 2017, 284, 4096–4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwinn, M.K.; Machleidt, T.; Zimmerman, K.; Eggers, C.T.; Dixon, A.S.; Hurst, R.; Hall, M.P.; Encell, L.P.; Binkowski, B.F.; Wood, K.V. CRISPR-mediated tagging of endogenous proteins with a luminescent peptide. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, 13, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grooms, K. Improving SARS-CoV-2 antibody detection with bioluminescence. Available online: https://www.promegaconnections.com/improving-sars-cov-2-antibody-detection-with-bioluminescence/ (accessed on 11 August 2020).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krasitskaya, V.V.; Bashmakova, E.E.; Frank, L.A. Coelenterazine-Dependent Luciferases as a Powerful Analytical Tool for Research and Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7465. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21207465

Krasitskaya VV, Bashmakova EE, Frank LA. Coelenterazine-Dependent Luciferases as a Powerful Analytical Tool for Research and Biomedical Applications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(20):7465. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21207465

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrasitskaya, Vasilisa V., Eugenia E. Bashmakova, and Ludmila A. Frank. 2020. "Coelenterazine-Dependent Luciferases as a Powerful Analytical Tool for Research and Biomedical Applications" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 20: 7465. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21207465

APA StyleKrasitskaya, V. V., Bashmakova, E. E., & Frank, L. A. (2020). Coelenterazine-Dependent Luciferases as a Powerful Analytical Tool for Research and Biomedical Applications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(20), 7465. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21207465