Bispicolyamine-Based Supramolecular Polymeric Gels Induced by Distinct Different Driving Forces with and Without Zn2+

Abstract

1. Introduction

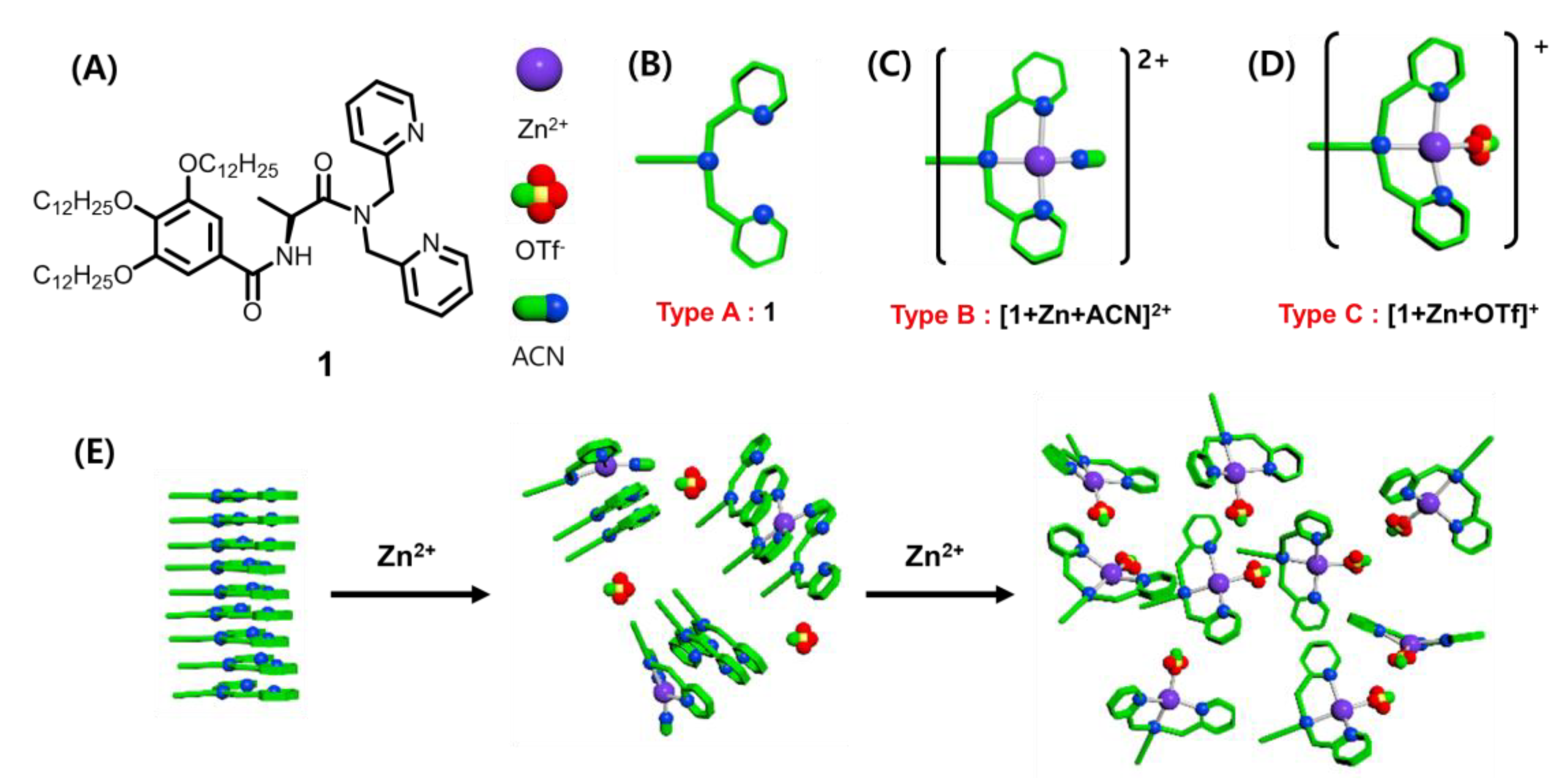

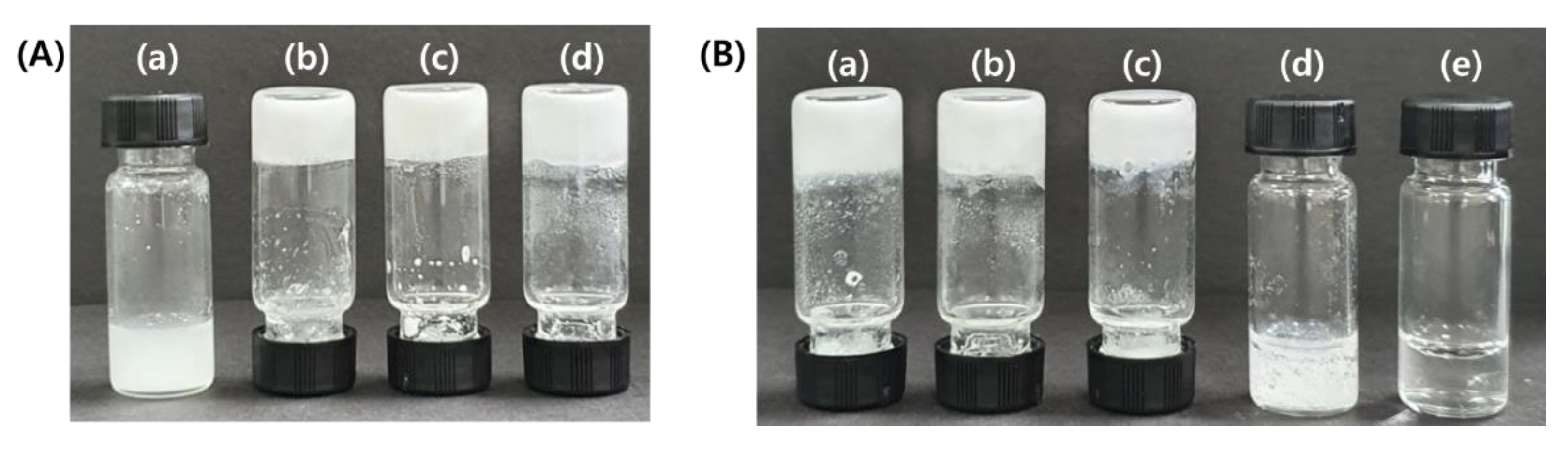

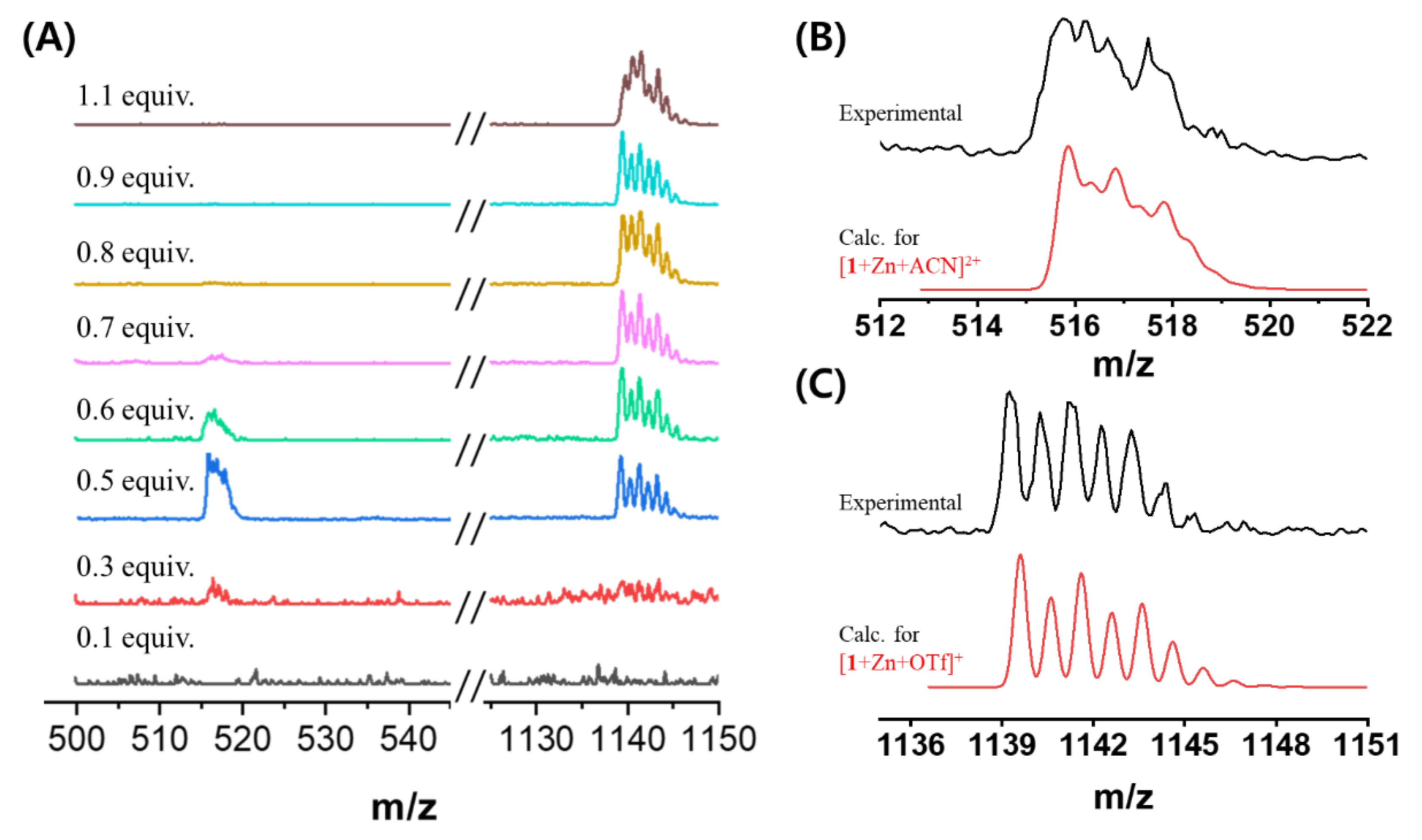

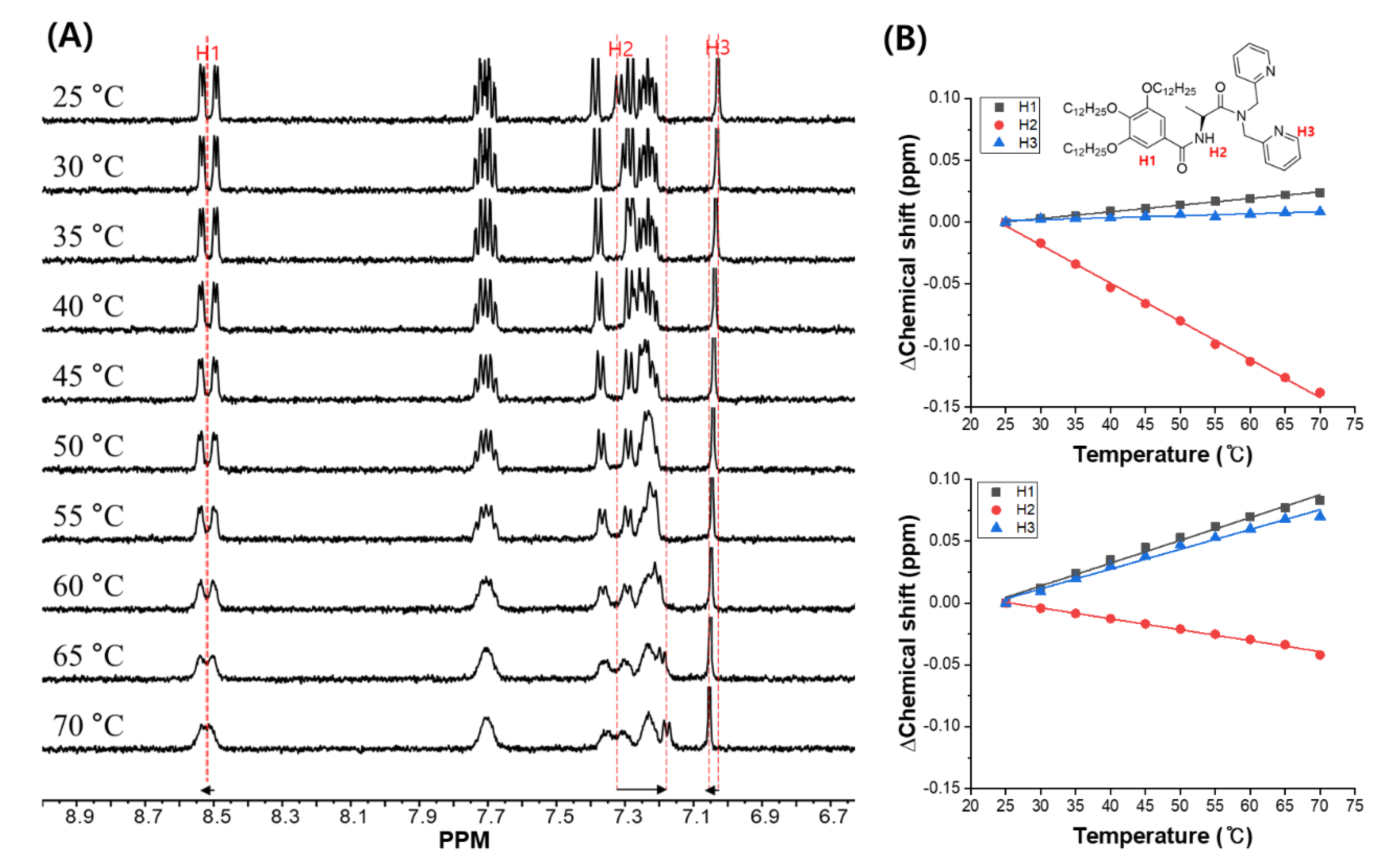

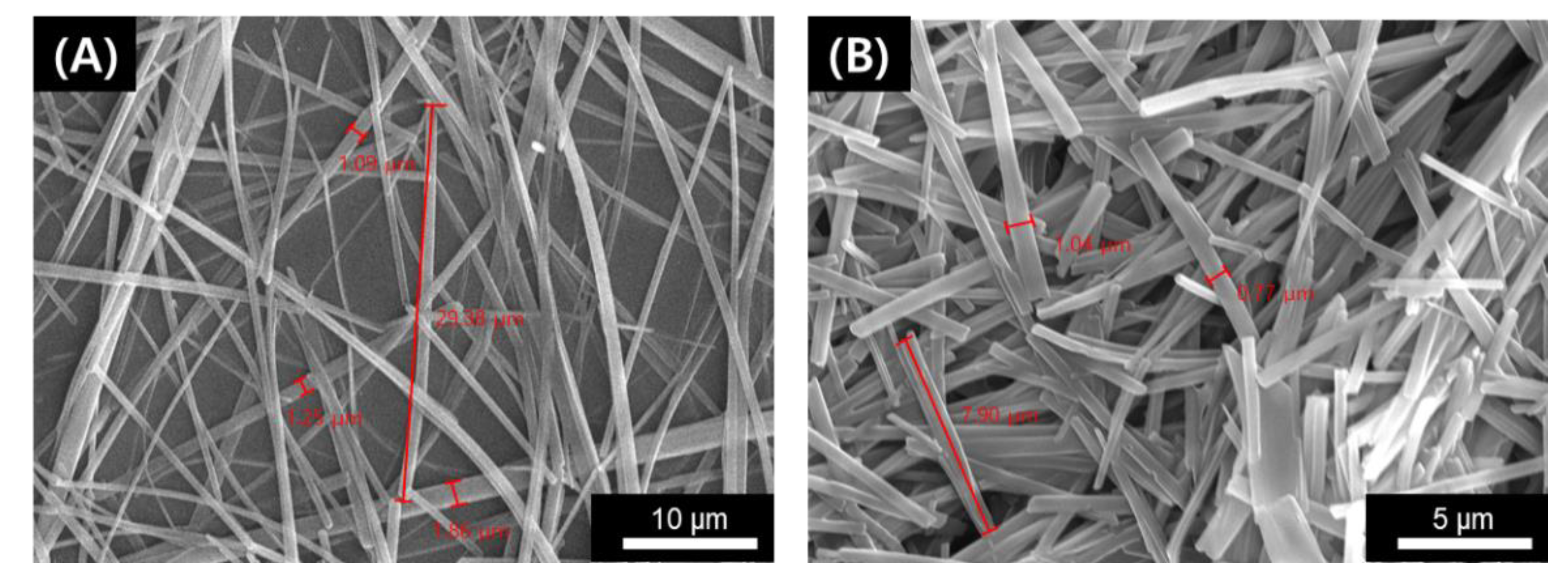

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagents and Instruments

3.2. Synthesis of N-[3,4,5-Tris(dodecyloxy)]benzoyl L-Alanine Methyl Ester (3)

3.3. Synthesis of N-[3,4,5-Tris(dodecyloxy)]benzoyl L-Alanine (2)

3.4. Synthesis of Gelator 1

3.5. Preparation of Supramolecular Gels

3.6. SEM Observation

3.7. Rheological Properties

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ye, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Yang, B.; Ji, F.; Dong, D.; Gao, L.; Cui, Y.; Yao, F. Physical Cross-Linking Starch-Based Zwitterionic Hydrogel Exhibiting Excellent Biocompatibility, Protein Resistance, and Biodegradability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 15710–15723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Olles, J.; Slavik, P.; Whitelaw, N.K.; Smith, D.K. Self-Assembled Gels Formed in Deep Eutectic Solvents: Supramolecular Eutectogels with High Ionic Conductivity. Angew. Chem. 2019, 58, 4173–4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, T.D.; Bucar, D.-K.; Baltrusaitis, J.; Flanagan, D.R.; Li, Y.; Ghorai, S.; Tivanski, A.V.; MacGillivray, L.R. Thixotropic Hydrogel Derived from a Product of an Organic Solid-State Synthesis: Properties and Densities of Metal-Organic Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 3365–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggeli, A.; Bell, M.; Boden, N.; Keen, J.N.; Knowles, P.F.; McLeish, T.C.; Pitkeathly, M.; Radford, S.E. Responsive gels formed by the spontaneous self-assembly of peptides into polymeric beta-sheet tapes. Nature 1997, 386, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; He, T.; Fan, Y.; Yuan, X.; Qiu, H.; Yin, S. Recent developments in the construction of metallacycle/metallacage-cored supramolecular polymers via hierarchical self-assembly. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 8036–8059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; He, T.; Shen, X.; Tang, D.; Yin, S. Fluorescent supramolecular polymers with aggregation induced emission properties. Polym. Chem. 2019, 10, 796–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Wang, F.; Zheng, B.; Huang, F. Stimuli-responsive supramolecular polymeric materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 6042–6065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuart, M.A.C.; Huck, W.T.S.; Genzer, J.; Müller, M.; Ober, C.; Stamm, M.; Sukhorukov, G.B.; Szleifer, I.; Tsukruk, V.V.; Urban, M.; et al. Emerging applications of stimuli-responsive polymer materials. Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, J.; Mao, Z.; Huang, X.; Wang, Z.; Hua, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, F.; He, Z.; et al. Supramolecular Polymer-Based Nanomedicine: High Therapeutic Performance and Negligible Long-Term Immunotoxicity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 8005–8019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Lopez, J.; Wang, H.; Wu, H.-C.; Niu, S.; Yan, H.; Wang, S.; Lei, T.; et al. Quadruple H-Bonding Cross-Linked Supramolecular Polymeric Materials as Substrates for Stretchable, Antitearing, and Self-Healable Thin Film Electrodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 5280–5289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Lu, W.; Yang, X.; He, J.; Le, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Serpe, M.J.; Huang, Y.; Chen, T. Bioinspired Anisotropic Hydrogel Actuators with On–Off Switchable and Color-Tunable Fluorescence Behaviors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1704568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.-H.; Deng, R.; Li, Z.; Du, X.-S.; Jia, Q.; Wang, X.-H.; Wang, C.-Y.; Meguellati, K.; Yang, Y.-W. Pillar [5]arene pseudo[1]rotaxane-based redox-responsive supramolecular vesicles for controlled drug release. Mater. Chem. Front. 2019, 3, 1427–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Song, G.; Jiao, Y.; Zheng, P.; Xu, J.-F.; Zhang, X. Dissipative Supramolecular Polymerization Powered by Light. CCS Chem. 2019, 1, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, M. “Let’s Twist Again” Double-Stranded, Triple-Stranded, and Circular Helicates. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 3457–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Q.; To, W.-P.; Yang, C.; Che, C.-M. The Metal–Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer Excited State and Supramolecular Polymerization of Luminescent Pincer PdII–Isocyanide Complexes. Angew. Chem. 2018, 57, 3089–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, J.L.-L.; Zou, T.; Liu, J.; Chen, T.; Chan, A.O.-Y.; Yang, C.; Lok, C.-N.; Che, C.-M. Luminescent platinum(ii) complexes with self-assembly and anti-cancer properties: Hydrogel, pH dependent emission color and sustained-release properties under physiological conditions. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 3823–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamiya, F.; Ousaka, N.; Yashima, E. Remote Control of the Planar Chirality in Peptide-Bound Metallomacrocycles and Dynamic-to-Static Planar Chirality Control Triggered by Solvent-Induced 310-to-α-Helix Transitions. Angew. Chem. 2015, 54, 14442–14446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ousaka, N.; Shimizu, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Iwata, T.; Itakura, M.; Taura, D.; Iida, H.; Furusho, Y.; Mori, T.; Yashima, E. Spiroborate-Based Double-Stranded Helicates: Meso-to-Racemo Isomerization and Ion-Triggered Springlike Motion of the Racemo-Helicate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 17027–17039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.E.; Nazemi, A.; Lunn, D.J.; Hayward, D.W.; Boott, C.E.; Hsiao, M.-S.; Harniman, R.L.; Davis, S.A.; Whittell, G.R.; Richardson, R.M.; et al. Dimensional Control and Morphological Transformations of Supramolecular Polymeric Nanofibers Based on Cofacially-Stacked Planar Amphiphilic Platinum (II) Complexes. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 9162–9175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kim, K.Y.; Jung, S.H.; Choi, Y.; Sato, H.; Jung, J.H. Different Origins of Strain-Induced Chirality Inversion of Co2+-Triggered Supramolecular Peptide Polymers. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 2074–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Kimura, H.; Okuhara, T.; Yamamura, M.; Nabeshima, T. A Hierarchical Self-Assembly System Built Up from Preorganized Tripodal Helical Metal Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 794–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittell, G.R.; Hager, M.D.; Schubert, U.S.; Manners, I. Functional soft materials from metallopolymers and metallosupramolecular polymers. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, A.; Schubert, U.S. Synthesis and characterization of metallo-supramolecular polymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 5311–5357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, M. Stimuli-responsive metallo-supramolecular polymer films: Design, synthesis and device fabrication. J. Mater. Chem. C 2014, 2, 9331–9341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Wang, Z.; Wu, J.; Tu, S.; Ding, K. Directed Orthogonal Self-Assembly of Homochiral Coordination Polymers for Heterogeneous Enantioselective Hydrogenation. Angew. Chem. 2010, 49, 3627–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langenstroer, A.; Dorca, Y.; Kartha, K.K.; Mayoral, M.J.; Stepanenko, V.; Fernández, G.; Sánchez, L. Exploiting N—H···Cl Hydrogen Bonding Interactions in Cooperative Metallosupramolecular Polymerization. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2018, 39, 1800191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taura, D.; Hioki, S.; Tanabe, J.; Ousaka, N.; Yashima, E. Cobalt (II)-Salen-Linked Complementary Double-Stranded Helical Catalysts for Asymmetric Nitro-Aldol Reaction. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 4685–4689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-J.; Yang, H.-B.; Shionoya, M. Chiral metallosupramolecular architectures. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 2555–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, M.H.-Y.; Leung, S.Y.-L.; Yam, V.W.-W. Controlling Self-Assembly Mechanisms through Rational Molecular Design in Oligo (p-phenyleneethynylene)-Containing Alkynylplatinum (II) 2,6-Bis (N-alkylbenzimidazol-2′-yl) pyridine Amphiphiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 7637–7646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, S.Y.-L.; Wong, K.M.-C.; Yam, V.W.-W. Self-assembly of alkynylplatinum (II) terpyridine amphiphiles into nanostructures via steric control and metal-metal interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 2845–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, V.C.-H.; Po, C.; Leung, S.Y.-L.; Chan, A.K.-W.; Yang, S.; Zhu, B.; Cui, X.; Yam, V.W.-W. Formation of 1D Infinite Chains Directed by Metal-Metal and/or π-π Stacking Interactions of Water-Soluble Platinum (II) 2,6-Bis (benzimidazol-2’-yl) pyridine Double Complex Salts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Q.; Xiao, X.-S.; To, W.-P.; Lu, W.; Chen, Y.; Low, K.-H.; Che, C.-M. Counteranion- and Solvent-Mediated Chirality Transfer in the Supramolecular Polymerization of Luminescent Platinum (II) Complexes. Angew. Chem. 2018, 57, 17189–17193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.Y.; Kim, J.; Moon, C.J.; Liu, J.; Lee, S.S.; Choi, M.Y.; Feng, C.; Jung, J.H. Co-Assembled Supramolecular Nanostructure of Platinum (II) Complex through Helical Ribbon to Helical Tubes with Helical Inversion. Angew. Chem. 2019, 58, 11709–11714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Jaworski, J.; Jung, J.H. Luminescent metal-organic framework-functionalized graphene oxide nanocomposites and the reversible detection of high explosives. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 8533–8540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, E.J.; Smith, B.D. Anion recognition using dimetallic coordination complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006, 250, 3068–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacoste, R.G.; Marttel, A.E. New Multidentate Ligands. I. Coordinating Tendencies of Polyamines Contaimng α-Pyridyl Groups with Divalent Metal Ions. Inorg. Chem. 1964, 3, 881–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultneh, Y.; Khan, A.R.; Blaise, D.; Chaudhry, S.; Ahvazi, B.; Marvey, B.B.; Butcher, R.J. Syntheses and structures of and catalysis of hydrolysis by Zn (II) complexes of chelating pyridyl donor ligands. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1999, 75, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhir, A.; Krämer, R.; Wolf, H. Zn2+-Dependent Peptide Nucleic Acids Probes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 6208–6209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Guo, Z. Fluorescent detection of zinc in biological systems: Recent development on the design of chemosensors and biosensors. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2004, 248, 205–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkup, G.K.; Burdette, S.C.; Lippard, S.J.; Tsien, R.Y. A New Cell-Permeable Fluorescent Probe for Zn2+. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 5644–5645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, N.C.; Brückner, C. DPA-substituted coumarins as chemosensors for zinc (ii): Modulation of the chemosensory characteristics by variation of the position of the chelate on the coumarin. Chem. Commun. 2004, 9, 1094–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.J.; Nolan, E.M.; Jaworski, J.; Burdette, S.C.; Sheng, M.; Lippard, S.J. Bright Fluorescent Chemosensor Platforms for Imaging Endogenous Pools of Neuronal Zinc. Chem. Biol. 2004, 11, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojida, A.; Mito-oka, Y.; Sada, K.; Hamachi, I. Molecular Recognition and Fluorescence Sensing of Monophosphorylated Peptides in Aqueous Solution by Bis (zinc (II)−dipicolylamine)-Based Artificial Receptors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 2454–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojida, A.; Inoue, M.-a.; Mito-oka, Y.; Hamachi, I. Cross-Linking Strategy for Molecular Recognition and Fluorescent Sensing of a Multi-phosphorylated Peptide in Aqueous Solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 10184–10185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Hong, J.-I. A Fluorescent Pyrophosphate Sensor with High Selectivity over ATP in Water. Angew. Chem. 2004, 43, 4777–4780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Im, J.H.; Son, S.U.; Chung, Y.K.; Hong, J.-I. An Azophenol-based Chromogenic Pyrophosphate Sensor in Water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 7752–7753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; O’Neil, E.J.; DiVittorio, K.M.; Smith, B.D. Anion-Mediated Phase Transfer of Zinc (II)-Coordinated Tyrosine Derivatives. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 3013–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Routasalo, T.; Helaja, J.; Kavakka, J.; Koskinen, A.M.P. Development of Bis(2-picolyl)amine–Zinc Chelates for Imidazole Receptors. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 2008, 3190–3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Park, B.K.; Eom, G.H.; Kim, S.H.; Park, H.M.; Choi, Y.S.; Jang, H.G.; Kim, C. Anion effects on construction of ZnII compounds with a chelating ligand bis (2-pyridylmethyl) amine and their catalytic activities. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2011, 366, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Goerls, H.; Plass, W. Facile high-yield synthesis of unsymmetric end-off compartmental double Schiff-base ligands: Easy access to mononuclear precursor and unsymmetric dinuclear complexes. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 75844–75854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalamera, D.; Sanders, E.; Vianello, R.; Marsavelski, A.; Pevec, A.; Turel, I.; Kirin, S.I. Synthesis and characterization of ML and ML2 metal complexes with amino acid substituted bis (2-picolyl) amine ligands. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 2845–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantalon Juraj, N.; Muratović, S.; Perić, B.; Šijaković Vujičić, N.; Vianello, R.; Žilić, D.; Jagličić, Z.; Kirin, S.I. Structural Variety of Isopropyl-bis (2-picolyl) amine Complexes with Zinc (II) and Copper (II). Cryst. Growth Des. 2020, 20, 2440–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Aprahamian, I. An emissive and pH switchable hydrazone-based hydrogel. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 11158–11161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appel, E.A.; del Barrio, J.; Loh, X.J.; Scherman, O.A. Supramolecular polymeric hydrogels. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 6195–6214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, D.; Yan, X.; Chen, J.; Dong, S.; Zheng, B.; Huang, F. Self-Healing Supramolecular Gels Formed by Crown Ether Based Host–Guest Interactions. Angew. Chem. 2012, 51, 7011–7015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Xu, D.; Chi, X.; Chen, J.; Dong, S.; Ding, X.; Yu, Y.; Huang, F. A Multiresponsive, Shape-Persistent, and Elastic Supramolecular Polymer Network Gel Constructed by Orthogonal Self-Assembly. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anokhin, D.V.; Lejnieks, J.; Mourran, A.; Zhu, X.; Keul, H.; Moeller, M.; Konovalov, O.; Erina, N.; Ivanov, D.A. Interplay between H-Bonding and Alkyl-Chain Ordering in Self-Assembly of Monodendritic L-Alanine Derivatives. ChemPhysChem 2012, 13, 1470–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, H.-J.; Hughes, A.D.; Draghici, B.; Lejnieks, J.; Leowanawat, P.; Bertin, A.; Otero De Leon, L.; Kulikov, O.V.; Chen, Y.; et al. “Single-Single” Amphiphilic Janus Dendrimers Self-Assemble into Uniform Dendrimersomes with Predictable Size. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 1554–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, J.; Kim, K.Y.; Kang, S.G.; Lee, S.S.; Lee, J.H.; Jung, J.H. Bispicolyamine-Based Supramolecular Polymeric Gels Induced by Distinct Different Driving Forces with and Without Zn2+. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4617. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21134617

Park J, Kim KY, Kang SG, Lee SS, Lee JH, Jung JH. Bispicolyamine-Based Supramolecular Polymeric Gels Induced by Distinct Different Driving Forces with and Without Zn2+. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(13):4617. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21134617

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Jaehyeon, Ka Young Kim, Seok Gyu Kang, Shim Sung Lee, Ji Ha Lee, and Jong Hwa Jung. 2020. "Bispicolyamine-Based Supramolecular Polymeric Gels Induced by Distinct Different Driving Forces with and Without Zn2+" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 13: 4617. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21134617

APA StylePark, J., Kim, K. Y., Kang, S. G., Lee, S. S., Lee, J. H., & Jung, J. H. (2020). Bispicolyamine-Based Supramolecular Polymeric Gels Induced by Distinct Different Driving Forces with and Without Zn2+. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(13), 4617. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21134617