Coffee Cascara as a Source of Natural Antimicrobials: Chemical Characterization and Activity Against ESKAPE Pathogens

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Total Soluble Solids of Cascara Extracts

2.2. Total Polyphenol and Flavonoid Content

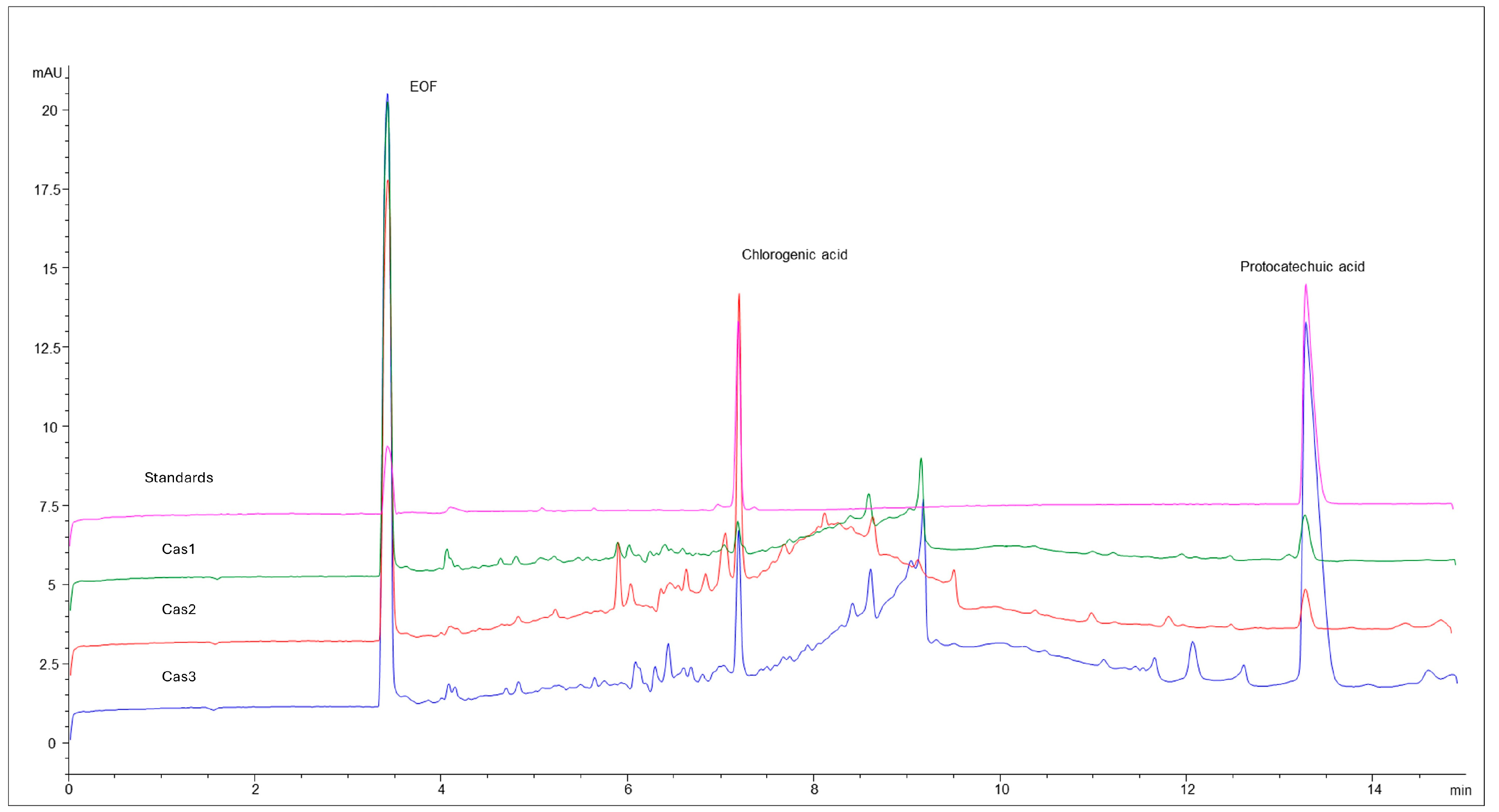

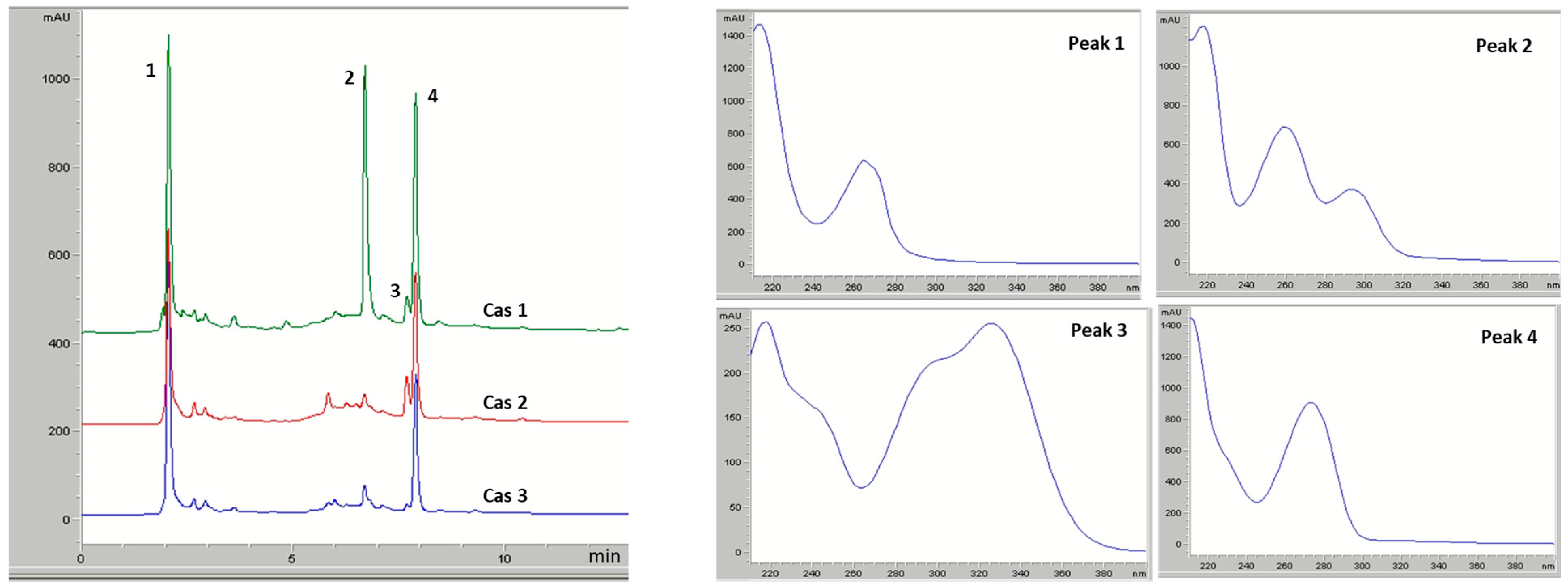

2.3. Phytochemical Analysis

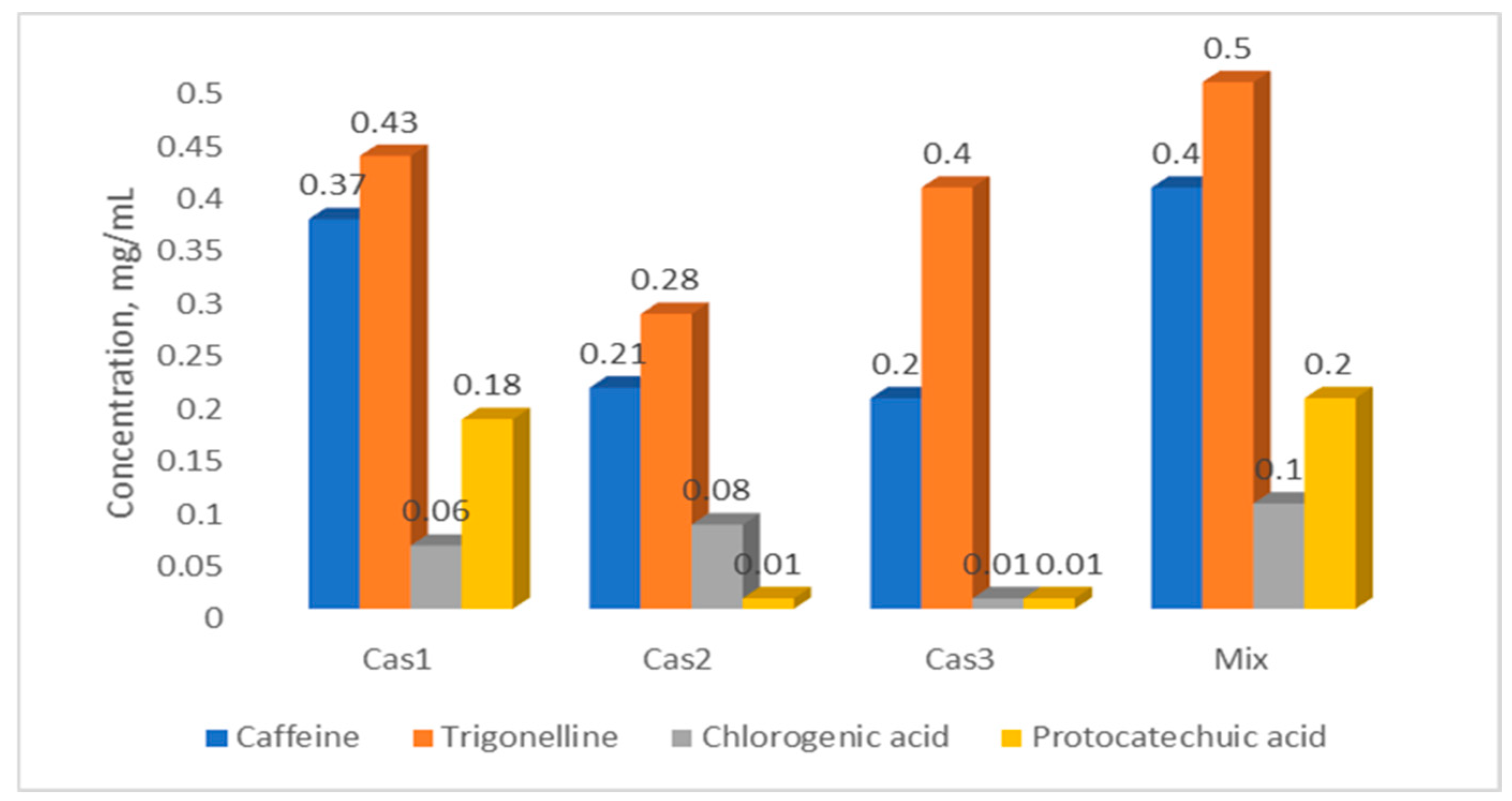

2.4. Quantification of Bioactive Compounds in Cascara Extracts

2.5. Antibacterial Properties

2.5.1. Antibacterial Activity of Cascara Extracts

2.5.2. Antibacterial Activity of Standards

2.5.3. Antibacterial Activity of Artificial Mixture

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Botanical Material and Extraction

3.2. Chemicals

3.3. Determination of Total Polyphenol and Flavonoid Content

3.4. Capillary Electrophoretic Analysis

3.5. HPLC-DAD-MS/MS Analyses

3.6. Bacterial Strains

3.7. Sample Preparation for Antibacterial Assay

3.8. Minimal Bactericidal Concentration (MBC)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Cas | Cascara |

| ESKAPE | Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter spp. |

| MBC | Minimal bactericidal concentration |

| MIC | Minimal inhibitory concentration |

| QE/L | Quercetin equivalent per liter |

| MDR | Multi-drug resistant |

| BGE | Background electrolyte |

| DAD | Diode-array detector |

| PCA | Protocatechuic acid |

| CGA | Chlorogenic acid |

| TA | Tannic acid |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant S. aureus |

References

- De Oliveira, D.M.P.; Forde, B.M.; Kidd, T.J.; Harris, P.N.A.; Schembri, M.A.; Beatson, S.A.; Paterson, D.L.; Walker, M.J. Antimicrobial Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, L.B. Federal funding for the study of antimicrobial resistance in nosocomial pathogens: No ESKAPE. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 197, 1079–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Antibacterial Agents in Clinical Development: An Analysis of the Antibacterial Clinical Development Pipeline; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Keita, K.; Darkoh, C.; Okafor, F. Secondary plant metabolites as potent drug candidates against antimicrobial-resistant pathogens. SN Appl. Sci. 2022, 4, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chassagne, F.; Samarakoon, T.; Porras, G.; Lyles, J.T.; Dettweiler, M.; Marquez, L.; Salam, A.M.; Shabih, S.; Farrokhi, D.R.; Quave, C.L. A Systematic Review of Plants With Antibacterial Activities: A Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Perspective. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 586548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, S.; Marquez, L.; Crandall, W.J.; Risener, C.J.; Quave, C.L. Recent advances in the discovery of plant-derived antimicrobial natural products to combat antimicrobial resistant pathogens: Insights from 2018–2022. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2023, 40, 1271–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DePaula, J.; Cunha, S.C.; Cruz, A.; Sales, A.L.; Revi, I.; Fernandes, J.; Ferreira, I.; Miguel, M.A.L.; Farah, A. Volatile Fingerprinting and Sensory Profiles of Coffee Cascara Teas Produced in Latin American Countries. Foods 2022, 11, 3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2022/47 (PDF, EUR-Lex). 2022. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg_impl/2022/47/oj/eng (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Ramirez-Coronel, M.A.; Marnet, N.; Kolli, V.S.; Roussos, S.; Guyot, S.; Augur, C. Characterization and estimation of proanthocyanidins and other phenolics in coffee pulp (Coffea arabica) by thiolysis-high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 1344–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Durán, L.V.; Favela-Torres, E.; Aguilar, C.N.; Saucedo-Castañeda, G. Coffee Pulp as Potential Source of Phenolic Bioactive Compounds. In Handbook of Research on Food Science and Technology; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 107–130. [Google Scholar]

- Heeger, A.; Kosinska-Cagnazzo, A.; Cantergiani, E.; Andlauer, W. Bioactives of coffee cherry pulp and its utilisation for production of Cascara beverage. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 969–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, X.; Liu, P.; Zhang, T.; Jelderks, J.A.; Corke, H. Preliminary Characterization of Phytochemicals and Polysaccharides in Diverse Coffee Cascara Samples: Identification, Quantification and Discovery of Novel Compounds. Foods 2022, 11, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.A.P.; Naghetini, C.C.; Santos, V.R.; Antonio, A.G.; Farah, A.; Glória, M.B.A. Influence of natural coffee compounds, coffee extracts and increased levels of caffeine on the inhibition of Streptococcus mutans. Food Res. Int. 2012, 49, 459–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khochapong, W.; Ketnawa, S.; Ogawa, Y.; Punbusayakul, N. Effect of in vitro digestion on bioactive compounds, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of coffee (Coffea arabica L.) pulp aqueous extract. Food Chem. 2021, 348, 129094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duangjai, A.; Suphrom, N.; Wungrath, J.; Ontawong, A.; Nuengchamnong, N.; Yosboonruang, A. Comparison of antioxidant, antimicrobial activities and chemical profiles of three coffee (Coffea arabica L.) pulp aqueous extracts. Integr. Med. Res. 2016, 5, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolat, E.; Saritas, S.; Duman, H.; Eker, F.; Akdasci, E.; Karav, S.; Witkowska, A.M. Polyphenols: Secondary Metabolites with a Biological Impression. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo, O.R.; Arévalo, A.C. Coffee’s Phenolic Compounds. A general overview of the coffee fruit’s phenolic composition. Revis Bionatura 2022, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmawati, A.; Nofitasari, D.; Rosmiati, M.; Taufik, I.; Abduh, M.Y. Evaluation of phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity, and sensory analysis of commercial cascara from different locations in Indonesia. Food Humanit. 2025, 5, 100791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel, P.; Jiménez, V.M. Functional properties of coffee and coffee by-products. Food Res. Int. 2012, 46, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpi, N.; Muzaifa, M.; Sulaiman, M.I.; Andini, R.; Kesuma, S.I. Chemical Characteristics of Cascara, Coffee Cherry Tea, Made of Various Coffee Pulp Treatments. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 709, 012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzaifa, M.; Nilda, C.; Widayat, H.; Rahmi, F.; Zahrina, H.; Darma, N. Characteristics of Cascara Brew Obtained from Wet, Dry and Wine Coffee Processing; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Febrianto, N.A.; Zhu, F. Coffee bean processing: Emerging methods and their effects on chemical, biological and sensory properties. Food Chem. 2023, 412, 135489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Muñoz, P.; Rebollo-Hernanz, M.; Braojos, C.; Cañas, S.; Gil-Ramirez, A.; Aguilera, Y.; Martin-Cabrejas, M.A.; Benitez, V. Comparative Investigation on Coffee Cascara from Dry and Wet Methods: Chemical and Functional Properties. Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2021, 6, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, Y.; Anhar, A.; Baihaqi, A.; Mushlih, A.M. Influence of farm altitude and variety on quality of arabica coffee cherry and bean grown in Gayo Highland, Indonesia. Int. J. Des. Nat. Ecodynamics 2024, 19, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Nie, Q.; Pan, W.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J.; Liu, Z.; Cai, S. Microbial composition, bioactive compounds, and sensory evaluation of Kombucha prepared with green tea and black tea. Beverage Plant Res. 2025, 5, e011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdani, C.G.; Pranowo, D. Total phenols content of green coffee (Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora) in East Java. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 230, 012093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehala, S.; Vaher, M.; Kaljurand, M. Characterization of phenolic profiles of Northern European berries by capillary electrophoresis and determination of their antioxidant activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 6484–6490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaher, M.; Koel, M. Separation of polyphenolic compounds extracted from plant matrices using capillary electrophoresis. J. Chromatogr. A 2003, 990, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neha Hande, A.H.; Hande, R.; Jatar, D.; Shinde, D. Chromatographic Fingerprinting of Medicinal Plants: A Reliable Tool for Quality Control. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 3, 538–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eka, L.; Ngatinem, N.; Rahayuningtyas, A.; Ulum, B. Determination of Caffeine Content at the Difference in Arabica and Robusta Coffee Roast Levels Using HPLC. BIO Web Conf. 2025, 158, 04011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinidis, N.; Franke, H.; Schwarz, S.; Lachenmeier, D.W. Risk Assessment of Trigonelline in Coffee and Coffee By-Products. Molecules 2023, 28, 3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bragina, O.; Kuhtinskaja, M.; Elisashvili, V.; Asatiani, M.; Kulp, M. Antibacterial Properties of Submerged Cultivated Targeting Gram-Negative Pathogens, Including. Sci 2025, 7, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasew, T.; Mekonnen, Y.; Gelana, T.; Redi-Abshiro, M.; Chandravanshi, B.S.; Ele, E.; Mohammed, A.M.; Mamo, H. In Vitro Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities of Roasted and Green Coffee Beans Originating from Different Regions of Ethiopia. Int. J. Food Sci. 2020, 2020, 8490492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woziwodzka, A.; Krychowiak-Masnicka, M.; Golunski, G.; Felberg, A.; Borowik, A.; Wyrzykowski, D.; Piosik, J. Modulatory Effects of Caffeine and Pentoxifylline on Aromatic Antibiotics: A Role for Hetero-Complex Formation. Molecules 2021, 26, 3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryanti, E.; Dwi, R.; Muhammad Eka, P.; Novita, A.; Indri, Y.; Vera, P.; Tjandrawati, M.; Indah, D.D.; Apriza, Y.; Muhammad, A.; et al. Chemical Composition, Antioxidant, Antibacterial, Antibiofilm, and Cytotoxic Activities of Robusta Coffee Extract (Coffea canephora). HAYATI J. Biosci. 2023, 30, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, F.M.S.; da Cunha Xavier, J.; Dos Santos, J.F.S.; de Matos, Y.; Tintino, S.R.; de Freitas, T.S.; Coutinho, H.D.M. Evaluation of antibacterial and modifying action of catechin antibiotics in resistant strains. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 115, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinsinwar, S.; Vadivel, V. Catechin isolated from cashew nut shell exhibits antibacterial activity against clinical isolates of MRSA through ROS-mediated oxidative stress. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 8279–8297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuete, V.; Nana, F.; Ngameni, B.; Mbaveng, A.T.; Keumedjio, F.; Ngadjui, B.T. Antimicrobial activity of the crude extract, fractions and compounds from stem bark of Ficus ovata (Moraceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 124, 556–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fifere, A.; Turin-Moleavin, I.A.; Rosca, I. Does Protocatechuic Acid Affect the Activity of Commonly Used Antibiotics and Antifungals? Life 2022, 12, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunanidhi, A.; Thomas, R.; van Belkum, A.; Neela, V. In vitro antibacterial and antibiofilm activities of chlorogenic acid against clinical isolates of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia including the trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole resistant strain. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 392058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yi, L.K.; Bai, Y.B.; Cao, M.Z.; Wang, W.W.; Shang, Z.X.; Li, J.J.; Xu, M.L.; Wu, L.F.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of Stevia extract against antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli by interfering with the permeability of the cell wall and the membrane. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1397906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Yadav, S.; Vaddu, S.; Thippareddi, H.; Kim, W.K. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of tannic acid as an antibacterial agent in broilers infected with Salmonella Typhimurium. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strompfova, V.; Stempelova, L.; Wolaschka, T. Antibacterial activity of plant-derived compounds and cream formulations against canine skin bacteria. Vet. Res. Commun. 2024, 48, 1459–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Shuang, W.; Qianwei, Q.; Xin, L.; Wei, P.; Hai, Y.; Yonghui, Z.; Xinbo, Y. Proteomic study of the inhibitory effects of tannic acid on MRSA biofilm. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1413669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, F.M.; Iorio, N.L.; Lobo, L.A.; dos Santos, K.R.N.; Farah, A.; Maia, L.C.; Antonio, A.G. Antibacterial Effect of Aqueous Extracts and Bioactive Chemical Compounds of Coffea canephora against Microorganisms Involved in Dental Caries and Periodontal Disease. Adv. Microbiol. 2014, 4, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.A.; Farah, A.; Silva, D.A.; Nunan, E.A.; Gloria, M.B. Antibacterial activity of coffee extracts and selected coffee chemical compounds against enterobacteria. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 8738–8743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machingauta, A.; Mukanganyama, S. Antibacterial Activity and Proposed Mode of Action of Extracts from Selected Zimbabwean Medicinal Plants against Acinetobacter baumannii. Adv. Pharmacol. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 2024, 8858665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, H.; Bairagi, A.; Mukherjee, A.; Prasad, A.K.; Roy, A.D.; Nayak, A. Multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: A study on its pathogenesis and therapeutics. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2025, 8, 100331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, E.; Rocha, T.S.; Prudencio, S.H. Potential of green and roasted coffee beans and spent coffee grounds to provide bioactive peptides. Food Chem. 2021, 348, 129061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Zeng, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, T.; Shen, M. Effect of chlorogenic acid on the quorum-sensing system of clinically isolated multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 1008–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Cao, X.; Pei, H.; Liu, P.; Song, Y.; Wu, Y. Anti-Biofilm Activity of Chlorogenic Acid against Pseudomonas Using Quorum Sensing System. Foods 2023, 12, 3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidova, S.; Galabov, A.S.; Satchanska, G. Antibacterial, Antifungal, Antiviral Activity, and Mechanisms of Action of Plant Polyphenols. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laanet, P.R.; Saar-Reismaa, P.; Joul, P.; Bragina, O.; Vaher, M. Phytochemical Screening and Antioxidant Activity of Selected Estonian Galium Species. Molecules 2023, 28, 2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brauer, A.; Remm, M. Bakteritüvede Iseloomustus Genoomi Andmete Põhjal. 2022. Available online: https://sisu.ut.ee/wp-content/uploads/sites/104/l6pparuanne_tuved.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2025).

| Cas1 | Cas2 | Cas3 |

|---|---|---|

| 23.94 ± 0.89 mg/mL | 28.37 ± 0.59 mg/mL | 26.40 ± 0.21 mg/mL |

| Sample | Total Polyphenols, | Total Flavonoids, |

|---|---|---|

| mg GAE/L ± SDV | mg QE/L ± SDV | |

| Cas1 | 802.2 ± 23.4 | 134.7 ± 13.2 |

| Cas2 | 403.5 ± 18.6 | 57.3 ± 4.6 |

| Cas3 | 536.8 ± 36.6 | 96.5 ± 11.0 |

| Peak No | RT, Min | λmax | MW | [M+H]+/ [M−H]− | Fragmentation | Identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.05 | 216, 264 | 137 | 138/- | - | Trigonelline |

| 2 | 6.67 | 218, 269, 294 | 154 | -/153 | 109 | Protocatechuic acid |

| 3 | 7.68 | 218, 326 | 354 | -/353 | 191 | Chlorogenic acid |

| 4 | 7.89 | 207, 273 | 194 | 195/- | 109 | Caffeine |

| Compound | Equation of Regression | LOD/LOQ, mg/mL | Repeatability/ Reproducibility *, % | Recovery *, % | R2 | Linear Range mg/mL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caffeine | y = 2838x − 2.099 | 0.001–0.003 | ≤4.4/≤8.9 | 86.2–102.8 | 0.9986 | 0.005–0.1 |

| Trigonelline | y = 886.7x + 1.9317 | 0.003–0.0011 | ≤4.9/≤8.3 | 87.6–103.1 | 0.9999 | 0.005–0.1 |

| Chlorogenic acid | y= 0.7104x + 1.6426 | 0.008–0.026 | ≤5.1/≤11.2 | 83.7–99.8 | 0.9936 | 0.01–0.15 |

| Protocatechuic acid | y = 1.8598x + 1.896 | 0.005–0.015 | ≤3.8/≤8.3 | 89.4–102.0 | 0.9966 | 0.01–0.15 |

| Sample | Caffeine | Trigonelline | Chlorogenic Acid | Protocatechuic Acid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas1 | 0.372 ± 0.031 | 0.434 ± 0.048 | 0.057 ± 0.002 | 0.178 ± 0.007 |

| Cas2 | 0.211 ± 0.022 | 0.286 ± 0.029 | 0.083 ± 0.006 | 0.008 ± 0.001 |

| Cas3 | 0.208 ± 0.026 | 0.407 ± 0.047 | 0.010 ± 0.001 | 0.012 ± 0.001 |

| Sample | S. aureus | E. faecium | K. pneumoniae | P. aeruginosa | A. baumannii | E. cloacae |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas1 | 0.75 | 2.99 | 23.89 | 5.97 | 0.75 | 11.95 |

| Cas2 | 7.09 | 7.09 | 28.37 | 28.37 | 7.09 | 28.37 |

| Cas3 | 1.65 | 3.30 | 26.40 | 3.30 | 3.30 | 26.40 |

| Standard | S. aureus | E. faecium | K. pneumoniae | P. aeruginosa | A. baumannii | E. cloacae |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protocatechuic acid | 0.125 | 0.025 | 0.200 | 0.200 | - | 0.200 |

| Catechin | 0.500 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Chlorogenic acid | 0.125 | 0.25 | - | - | 0.500 | - |

| Trigonelline | 0.016 | 0.063 | - | - | 0.063 | 0.500 |

| Caffeine | 0.125 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Tannic acid | 0.016 | 0.500 | - | - | 0.500 | - |

| S. aureus | E. faecium | K. pneumoniae | P. aeruginosa | A. baumannii | E. cloacae | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas1_caff | 0.010 | 0.050 | 0.370 | 0.090 | 0.010 | 0.190 |

| Cas1_trig | 0.010 | 0.050 | 0.430 | 0.110 | 0.010 | 0.220 |

| Cas1_proto | 0.010 | 0.020 | 0.178 | 0.040 | 0.010 | 0.090 |

| Cas1_chl | 0.000 | 0.070 | 0.057 | 0.010 | 0.000 | 0.030 |

| Sum | 0.030 | 0.190 | 1.035 | 0.250 | 0.030 | 0.530 |

| Cas2_caff | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.210 | 0.210 | 0.053 | 0.210 |

| Cas2_trig | 0.070 | 0.070 | 0.280 | 0.280 | 0.070 | 0.280 |

| Cas2_proto | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.008 |

| Cas2_chl | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.083 | 0.083 | 0.021 | 0.083 |

| Sum | 0.150 | 0.150 | 0.581 | 0.581 | 0.146 | 0.581 |

| Cas3_caff | 0.013 | 0.025 | 0.200 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.200 |

| Cas3_trig | 0.025 | 0.050 | 0.400 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.400 |

| Cas3_proto | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.012 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.012 |

| Cas3_chl | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.010 |

| Sum | 0.039 | 0.078 | 0.622 | 0.030 | 0.030 | 0.622 |

| S. aureus | E. faecium | K. pneumoniae | P. aeruginosa | A. baumanii | E. cloacae | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mix_caff | 0.013 | 0.050 | 0.400 | 0.400 | 0.050 | 0.200 |

| Mix_trig | 0.016 | 0.063 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.063 | 0.250 |

| Mix_proto | 0.006 | 0.025 | 0.200 | 0.200 | 0.025 | 0.100 |

| Mix_chl | 0.003 | 0.013 | 0.100 | 0.100 | 0.013 | 0.050 |

| Mix_sum | 0.040 | 0.150 | 1.200 | 1.200 | 0.150 | 0.600 |

| Customer | Variety | Processing | Origin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas1 | Shokunin coffee collective, The Netherlands | Castillo | Fully washed | Columbia |

| Cas2 | Green plantation, Czech Republic | Bourbon | Natural | Panama |

| Cas3 | Gust, Belgium | Caturra Catuai | Natural | Costa Rica |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vaher, M.; Bragina, O. Coffee Cascara as a Source of Natural Antimicrobials: Chemical Characterization and Activity Against ESKAPE Pathogens. Molecules 2026, 31, 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030403

Vaher M, Bragina O. Coffee Cascara as a Source of Natural Antimicrobials: Chemical Characterization and Activity Against ESKAPE Pathogens. Molecules. 2026; 31(3):403. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030403

Chicago/Turabian StyleVaher, Merike, and Olga Bragina. 2026. "Coffee Cascara as a Source of Natural Antimicrobials: Chemical Characterization and Activity Against ESKAPE Pathogens" Molecules 31, no. 3: 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030403

APA StyleVaher, M., & Bragina, O. (2026). Coffee Cascara as a Source of Natural Antimicrobials: Chemical Characterization and Activity Against ESKAPE Pathogens. Molecules, 31(3), 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030403