Garlic-Derived Phytochemical Candidates Predicted to Disrupt SARS-CoV-2 RBD–ACE2 Binding and Inhibit Viral Entry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Garlic Bioactive Compounds

2.2. GC-MS Analysis of TL Bulbs Aqueous Fraction

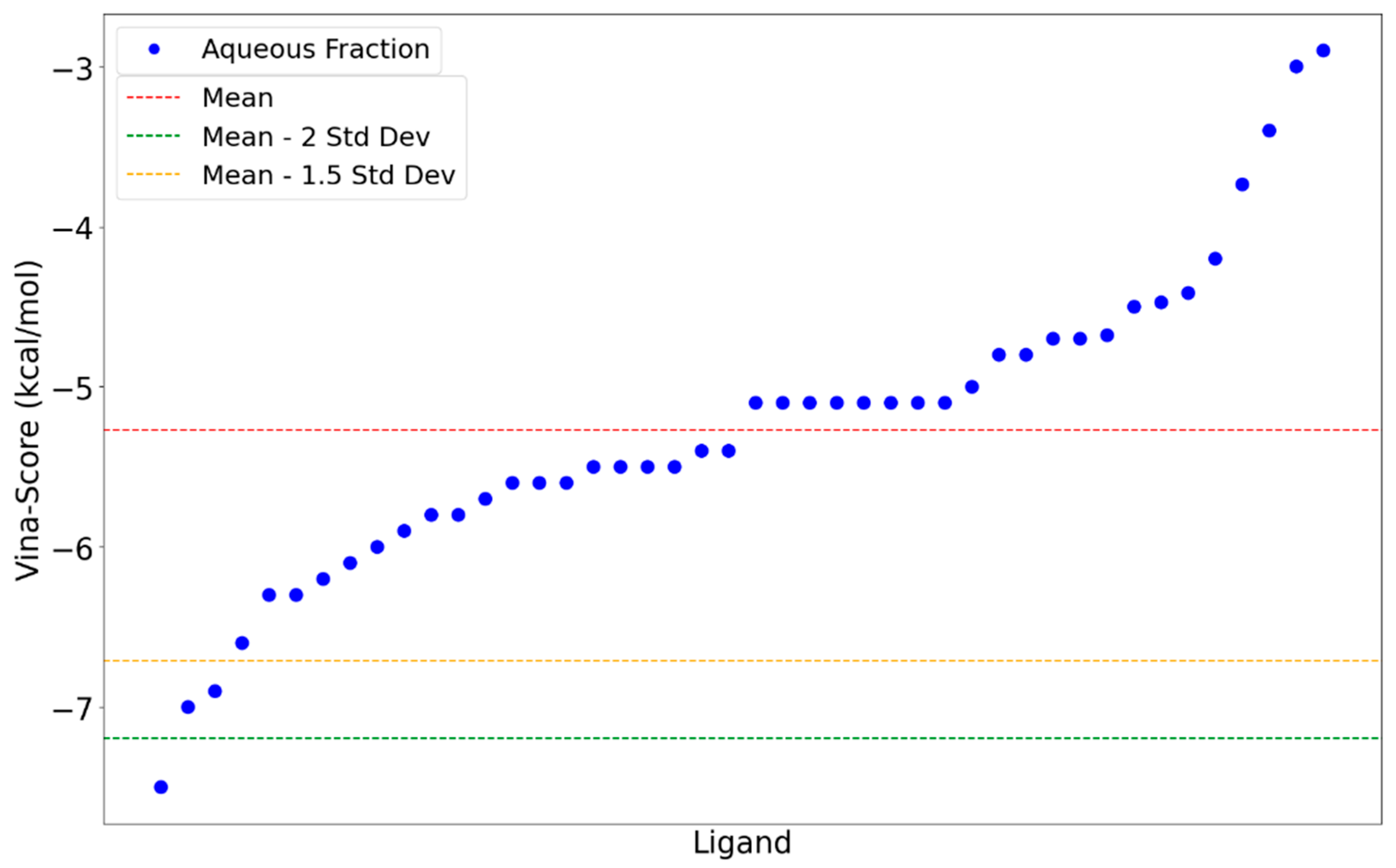

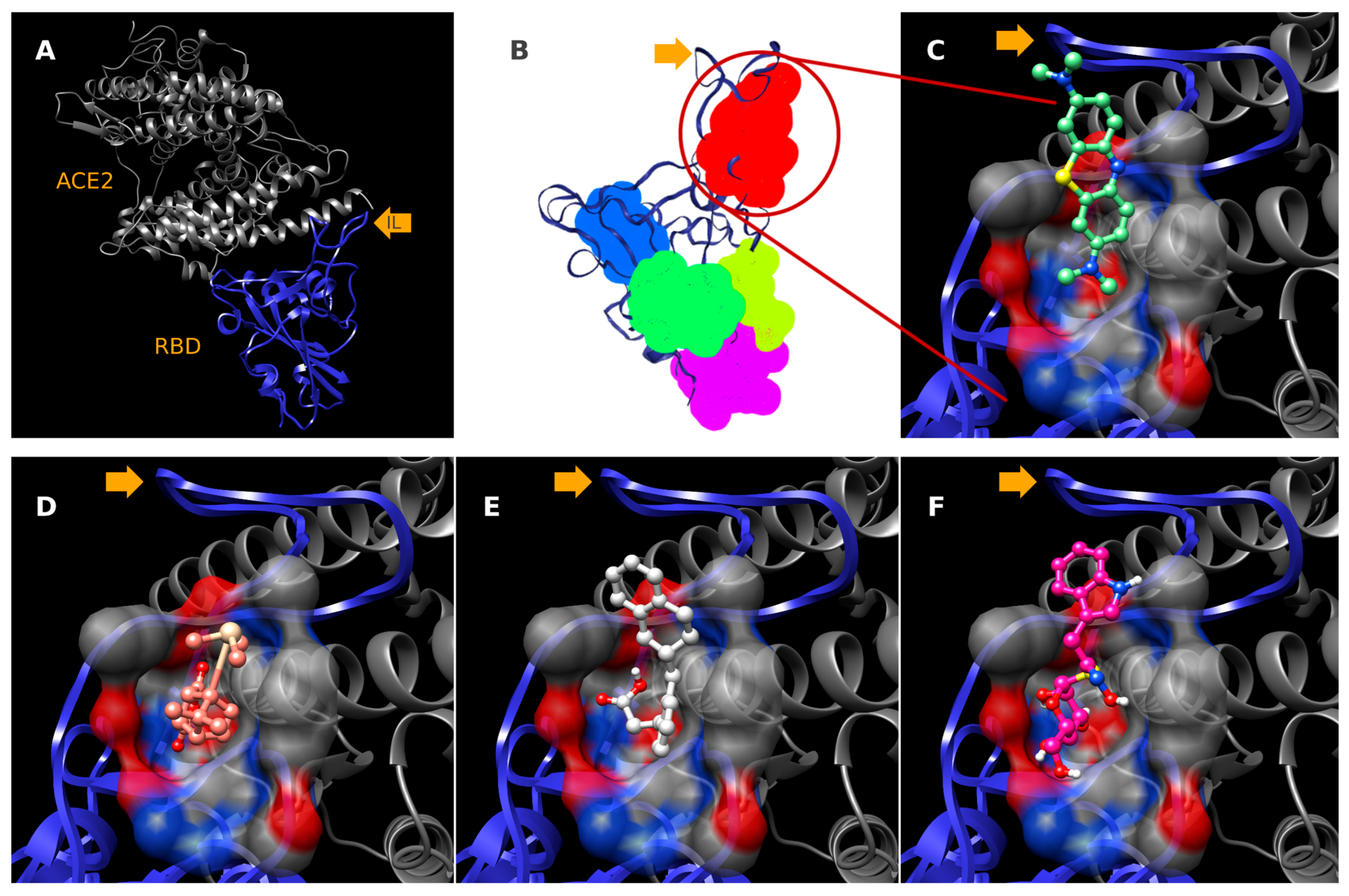

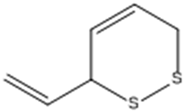

2.3. Molecular Docking

3. Discussion

3.1. Evaluation of Garlic Anti-SARS-CoV-2-RBD Therapeutic Potential

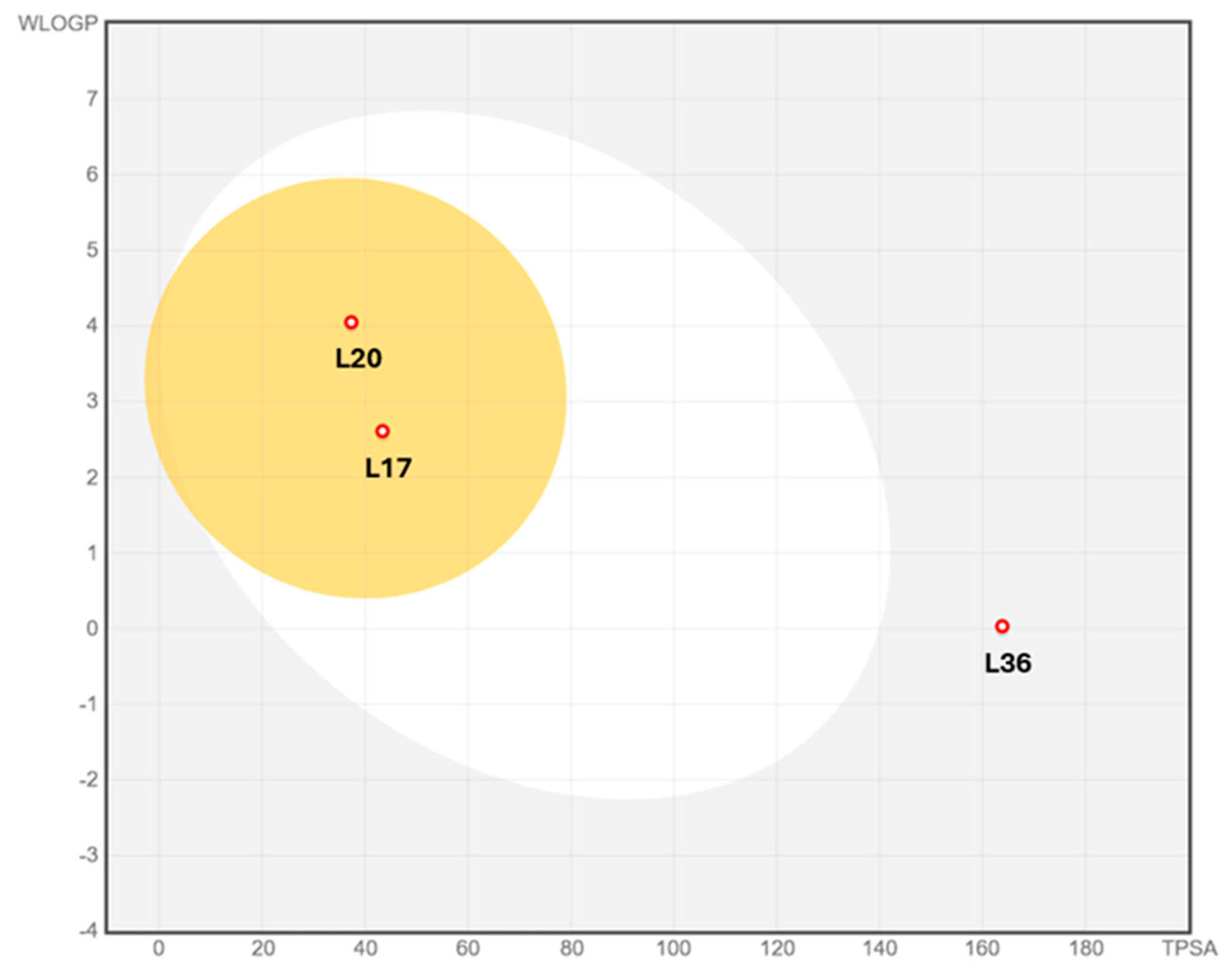

3.2. Pharmacokinetic Profiles and Toxicity In Silico

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Garlic Cultivation and Extraction

4.2. Fractioning of Crude Extracts

4.3. ELISA Immunological Assays

4.4. Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry

4.5. RBD-Compound Molecular Docking

4.6. Physicochemical, Pharmacokinetic, and Bioavailability Analyses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization COVID-19 Deaths | WHO COVID-19 Dashboard. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/deaths (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Kim, C.-H. Anti–SARS-CoV-2 Natural Products as Potentially Therapeutic Agents. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 590509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M.; Liang, C. Human Coronaviruses: The Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 and Management of COVID-19. Virus Res. 2022, 319, 198882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570371/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK570371.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Choi, H.S.; Choi, A.Y.; Kopp, J.B.; Winkler, C.A.; Cho, S.K. Review of COVID-19 Therapeutics by Mechanism: From Discovery to Approval. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2024, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi, Y.; Gorabi, A.M.; Talaei, S.; Beiraghdar, F.; Akbarzadeh, A.; Tarhriz, V.; Mellatyar, H. An Overview on the Treatments and Prevention against COVID-19. Virol. J. 2023, 20, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern as of 31 October 2025. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19/variants-concern (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Atanasov, A.G.; Zotchev, S.B.; Dirsch, V.M.; Supuran, C.T. Natural Products in Drug Discovery: Advances and Opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamulka, J.; Jeruszka-Bielak, M.; Górnicka, M.; Drywień, M.E.; Zielinska-Pukos, M.A. Dietary Supplements during COVID-19 Outbreak. Results of Google Trends Analysis Supported by PLifeCOVID-19 Online Studies. Nutrients 2021, 13, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orisakwe, O.E.; Orish, C.N.; Nwanaforo, E.O. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) and Africa: Acclaimed Home Remedies. Sci. Afr. 2020, 10, e00620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebaibi, M.; Bousta, D.; Bourhia, M.; Baammi, S.; Salamatullah, A.M.; Nafidi, H.-A.; Hoummani, H.; Achour, S. Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants Used against COVID-19. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 2085297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamees, A.; Awadi, S.; Rawashdeh, S.; Talafha, M.; Bani-Issa, J.; Alkadiri, M.A.S.; Zoubi, M.S.A.; Hussein, E.; Fattah, F.A.; Bashayreh, I.H.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Jordanian Eating and Nutritional Habits. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kladar, N.; Bijelić, K.; Gatarić, B.; Bubić Pajić, N.; Hitl, M. Phytotherapy and Dietotherapy of COVID-19—An Online Survey Results from Central Part of Balkan Peninsula. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlozi, S.H. The Role of Natural Products from Medicinal Plants against COVID-19: Traditional Medicine Practice in Tanzania. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuqbil, M.; Alshaikh, S.; Alrumayh, N.; Alnahdi, F.; Fallatah, E.; Almutairi, S.; Imran, M.; Kamal, M.; Almehmadi, M.; Alsaiari, A.A.; et al. Role of Natural Products in the Management of COVID-19: A Saudi Arabian Perspective. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguli, S.; Howlader, S.; Dey, K.; Barua, S.; Islam, M.N.; Begum, A.; Sobahan, M.A.; Chakraborty, R.R.; Hawlader, M.D.H.; Biswas, P.K. Association of Food Habit with the COVID-19 Severity and Hospitalization: A Cross-Sectional Study among the Recovered Individuals in Bangladesh. Nutr. Health 2022, 28, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, S.V.; Pal, R.; Vaiphei, K.; Sharma, S.K.; Ola, R.P. Garlic in Health and Disease. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2011, 24, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency Allii Sativi Bulbus—Herbal Medicinal Product | European Medicines Agency (EMA). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/herbal/allii-sativi-bulbus (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- World Health Organization. WHO Monographs on Selected Medicinal Plants; World Health Organization, Ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999; ISBN 978-92-4-154517-4. [Google Scholar]

- El-Saber Batiha, G.; Magdy Beshbishy, A.G.; Wasef, L.; Elewa, Y.H.A.; A. Al-Sagan, A.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Taha, A.E.; M. Abd-Elhakim, Y.; Prasad Devkota, H. Chemical Constituents and Pharmacological Activities of Garlic (Allium sativum L.): A Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Universidad Autónoma de México :: :: Términos—Atlas de las Plantas de la Medicina Tradicional Mexicana :: Biblioteca Digital de la Medicina Tradicional Mexicana. Available online: http://www.medicinatradicionalmexicana.unam.mx/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Rouf, R.; Uddin, S.J.; Sarker, D.K.; Islam, M.T.; Ali, E.S.; Shilpi, J.A.; Nahar, L.; Tiralongo, E.; Sarker, S.D. Antiviral Potential of Garlic (Allium sativum) and Its Organosulfur Compounds: A Systematic Update of Pre-Clinical and Clinical Data. Trends in Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 104, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khubber, S.; Hashemifesharaki, R.; Mohammadi, M.; Gharibzahedi, S.M.T. Garlic (Allium sativum L.): A Potential Unique Therapeutic Food Rich in Organosulfur and Flavonoid Compounds to Fight with COVID-19. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donma, M.M.; Donma, O. The Effects of Allium sativum on Immunity within the Scope of COVID-19 Infection. Med. Hypotheses 2020, 144, 109934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.K.; Pandey, R.K.; Shukla, S.S.; Pandey, P. A Review on Corona Virus and Treatment Approaches with Allium Sativam. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 7, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rayo Camacho-Corona, M.; Camacho-Morales, A.; Góngora-Rivera, F.; Escamilla-García, E.; Morales-Landa, J.L.; Andrade-Medina, M.; Herrera-Rodulfo, A.F.; García-Juárez, M.; García-Espinosa, P.; Stefani, T.; et al. Immunomodulatory Effects of Allium sativum L. and Its Constituents against Viral Infections and Metabolic Diseases. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2022, 22, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsebai, M.F.; Albalawi, M.A. Essential Oils and COVID-19. Molecules 2022, 27, 7893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuy, B.T.P.; My, T.T.A.; Hai, N.T.T.; Hieu, L.T.; Hoa, T.T.; Thi Phuong Loan, H.; Triet, N.T.; Anh, T.T.V.; Quy, P.T.; Tat, P.V.; et al. Investigation into SARS-CoV-2 Resistance of Compounds in Garlic Essential Oil. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 8312–8320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekh, S.; Reddy, K.K.A.; Gowd, K.H. In Silico Allicin Induced S-Thioallylation of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease. J. Sulfur Chem. 2021, 42, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parashar, A.; Shukla, A.; Sharma, A.; Behl, T.; Goswami, D.; Mehta, V. Reckoning γ-Glutamyl-S-Allylcysteine as a Potential Main Protease (Mpro) Inhibitor of Novel SARS-CoV-2 Virus Identified Using Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2021, 47, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bojadzic, D.; Alcazar, O.; Buchwald, P. Methylene Blue Inhibits the SARS-CoV-2 Spike–ACE2 Protein-Protein Interaction–a Mechanism That Can Contribute to Its Antiviral Activity Against COVID-19. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 600372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, H.A.; Borrel, A.; Geneix, C.; Patitjean, M.; Regard, L.; Camproux, A.-C. PockDrug-Server: A New Web Server for Predicting Pocket Druggability on Holo and Apo Proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W436–W442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refaat Fahim, J.; Darwish, A.G.; El Zawily, A.; Wells, J.; Abourehab, M.A.S.; Yehia Desoukey, S.; Zekry Attia, E. Exploring the Volatile Metabolites of Three Chorisia Species: Comparative Headspace GC–MS, Multivariate Chemometrics, Chemotaxonomic Significance, and Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Potential. Saudi Pharma. J. 2023, 31, 706–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nursyifa Fadiyah, N.; Megawati, G.; Erlangga Luftimas, D. Potential of Omega 3 Supplementation for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Scoping Review. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2022, 15, 3915–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiffer, A.L.; Garlick, J.M.; Wu, Y.; Wotring, J.W.; Arora, S.; Harmata, A.S.; Bochar, D.A.; Stephenson, C.J.; Soellner, M.B.; Sexton, J.Z.; et al. TMPRSS2 Inhibitor Discovery Facilitated through an In Silico and Biochemical Screening Platform. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Y.; Slanař, O.; Krausz, K.W.; Chen, C.; Slavík, J.; McPhail, K.L.; Zabriskie, T.M.; Perlík, F.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Idle, J.R. 3,4-Dehydrodebrisoquine, a Novel Debrisoquine Metabolite Formed from 4-Hydroxydebrisoquine That Affects the CYP2D6 Metabolic Ratio. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2006, 34, 1563–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zou, S.; Qiu, S.; Yang, H.; Hu, Y.; Lin, G.; Yao, X.; Liu, S.; Zou, M. Identification of Alpha-Linolenic Acid as a Broad-Spectrum Antiviral against Zika, Dengue, Herpes Simplex, Influenza Virus and SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Antivir. Res. 2023, 216, 105666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Xie, F.; Huang, W.; Hu, M.; Yan, Q.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, L. The Review of Alpha-Linolenic Acid: Sources, Metabolism, and Pharmacology. Phytother. Res. 2022, 36, 164–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusumah, D.; Wakui, M.; Murakami, M.; Xie, X.; Yukihito, K.; Maeda, I. Linoleic Acid, α-Linolenic Acid, and Monolinolenins as Antibacterial Substances in the Heat-Processed Soybean Fermented with Rhizopus Oligosporus. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2020, 84, 1285–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loria, R.M.; Padgett, D.A. α-Linolenic Acid Prevents the Hypercholesteremic Effects of Cholesterol Addition to a Corn Oil Diet. J. Nutr. Biochem. 1997, 8, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luisetto, R.; Scarpa, M.; Villano, G.; Martini, A.; Quarta, S.; Ruvoletto, M.; Guerra, P.; Scarpa, M.; Chinellato, M.; Biasiolo, A.; et al. 1-Piperidine Propionic Acid Protects from Septic Shock Through Protease Receptor 2 Inhibition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinellato, M.; Gasparotto, M.; Quarta, S.; Ruvoletto, M.; Biasiolo, A.; Filippini, F.; Spiezia, L.; Cendron, L.; Pontisso, P. 1-Piperidine Propionic Acid as an Allosteric Inhibitor of Protease Activated Receptor-2. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, W.; Yu, S.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, B. Recent Research on 3-Phenyllactic Acid, a Broad-Spectrum Antimicrobial Compound. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 95, 1155–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parappilly, S.J.; Radhakrishnan, E.K.; George, S.M. Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Activity of Human Gut Lactic Acid Bacteria. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2024, 55, 3529–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhao, M.; Liu, F.; Zeng, S.; Hu, J. Identification of 2,3-Dihydro-3,5-Dihydroxy-6-Methyl-4H-Pyran-4-One as a Strong Antioxidant in Glucose–Histidine Maillard Reaction Products. Food Res. Int. 2013, 51, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čechovská, L.; Cejpek, K.; Konečný, M.; Velíšek, J. On the Role of 2,3-Dihydro-3,5-Dihydroxy-6-Methyl-(4H)-Pyran-4-One in Antioxidant Capacity of Prunes. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2011, 233, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Bai, B.; Sun, Z.; Cai, L.; Fu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xi, G. Effect of Hydroxyl on Antioxidant Properties of 2,3-Dihydro-3,5-Dihydroxy-6-Methyl-4H-Pyran-4-One to Scavenge Free Radicals. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 34456–34461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, R.; Marni, R.; Chakraborty, A.; Kamal, M.A. Diallyl Disulfide and Diallyl Trisulfide in Garlic as Novel Therapeutic Agents to Overcome Drug Resistance in Breast Cancer. J. Pharm. Anal. 2022, 12, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Yue, Z.; Nie, L.; Zhao, P.; Zhu, K.; Wang, Q. Biological Functions of Diallyl Disulfide, a Garlic-Derived Natural Organic Sulfur Compound. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 5103626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.G.; Park, J.K. Comparison of Inhibitory Activity of Bioactive Molecules on the Dextransucrase from Streptococcus Mutans. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 7495–7503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onoda, T.; Morikawa, S.; Harada, T.; Morikawa, K. Antitumor Activity of D-Mannosamine In Vitro: Cytotoxic Effect Produced by Mannosamine in Combination with Free Fatty Acids on Human Leukemia T-Cell Lines. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 1985, 15, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Yu, J.; Xu, H.; Xu, K.; Sohail, M.; Wang, J.; Ning, H.; Zhang, J.; Yu, B. Recent Research Advances in Multi-Functional Diallyl Trisulfide (DATS): A Comprehensive Review of Characteristics, Metabolism, Pharmacodynamics, Applications, and Drug Delivery Systems. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 4381–4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barman, H.; Kabir, M.E.; Borah, A.; Afzal, N.U.; Loying, R.; Sharmah, B.; Ibeyaima, A.; Kalita, J.; Manna, P. Therapeutic Uses of Dietary Organosulfur Compounds in Response to Viral (SARS-CoV-2)/Bacterial Infection, Inflammation, Cancer, Oxidative Stress, Cardiovascular Diseases, Obesity, and Diabetes. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, e00731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Su, B. Diallyl Trisulfide Intervention in Redox Homeostasis and Its Multitarget Antitumor Effects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 16011–16027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Gao, Z.; Song, J.; Jin, L.; Liang, Z. The Potential of Diallyl Trisulfide for Cancer Prevention and Treatment, with Mechanism Insights. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1450836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novakovic, J.; Muric, M.; Bradic, J.; Ramenskaya, G.; Jakovljevic, V.; Jeremic, N. Diallyl Trisulfide and Cardiovascular Health: Evidence and Potential Molecular Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariga, T.; Takeda, A.; Teramoto, S.; Seki, T. Inhibition Site of Methylallyl Trisulfide: A Volatile Oil Component of Garlic, in the Platelet Arachidonic Acid Cascade. In Food Factors for Cancer Prevention; Ohigashi, H., Osawa, T., Terao, J., Watanabe, S., Yoshikawa, T., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 1997; pp. 231–234. [Google Scholar]

- Seki, T.; Hosono, T. Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases by Garlic-Derived Sulfur Compounds. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2015, 61, S83–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallima, H.; El Ridi, R. Arachidonic Acid: Physiological Roles and Potential Health Benefits – A Review. J. Adv. Res. 2018, 11, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, O.A.; Ogunlakin, A.D.; Gyebi, G.A.; Ayokunle, D.I.; Odugbemi, A.I.; Babatunde, D.E.; Ajayi-Odoko, O.A.; Iyobhebhe, M.; Ezea, S.C.; Akintayo, C.O.; et al. GC-MS Chemical Profiling, Antioxidant, Anti-Diabetic, and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Ethyl Acetate Fraction of Spilanthes Filicaulis (Schumach. and Thonn.) C.D. Adams Leaves: Experimental and Computational Studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1235810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.Y.; Seetharaman, R.; Ko, M.J.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, T.H.; Yoon, M.K.; Kwak, J.H.; Lee, S.J.; Bae, Y.S.; Choi, Y.W. Ethyl Linoleate from Garlic Attenuates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Production by Inducing Heme Oxygenase-1 in RAW264.7 Cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2014, 19, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, S.; Kim, Y.-S.; Jung, E.; Lim, J.; Jung, K.S.; Kim, M.-O.; Lee, J.; Park, D. Melanogenesis Inhibitory Effect of Fatty Acid Alkyl Esters Isolated from Oxalis Triangularis. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2010, 33, 1242–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, G.-A.; Kim Cho, S. Ethyl Linoleate Inhibits α-MSH-Induced Melanogenesis through Akt/GSK3β/β-Catenin Signal Pathway. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2018, 22, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obregón Medina, J.R. Etiología, incidencia y daños por pudrición seca de ajo (Allium sativum L.) en La Ascensión, Aramberri, Nuevo León. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, San Nicolás de los Garza, Mexico, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Calle, M.; Priego-Capote, F.; de Castro, M.D.L. HS–GC/MS Volatile Profile of Different Varieties of Garlic and Their Behavior under Heating. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 3843–3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Rodulfo, A.; Andrade-Medina, M.; Carrillo-Tripp, M.; Herrera-Rodulfo, A.; Andrade-Medina, M.; Carrillo-Tripp, M. Repurposing Drugs as Potential Therapeutics for the SARS-Cov-2 Viral Infection: Automatizing a Blind Molecular Docking High-Throughput Pipeline. In Molecular Docking—Recent Advances; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-1-80356-468-5. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Shah, S. Structure-Based Virtual Screening. In Protein Bioinformatics: From Protein Modifications and Networks to Proteomics; Wu, C.H., Arighi, C.N., Ross, K.E., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 111–124. ISBN 978-1-4939-6783-4. [Google Scholar]

| Compound | Structure | Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Target Protein | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

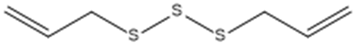

| Tetrasulfide, di-2-propenyl. |  | ACE2 | [28] |

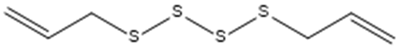

| Diallyl disulfide. |  | ACE2 | [28] |

| 3-Vinyl-1,2-dithiacyclohex-4-ene. |  | ACE2 | [28] |

| Diallyl trisulfide. |  | ACE2 | [28] |

| Diallyl tetrasulfide. |  | ACE2 | [28] |

| Allicin. (Allyl 2-propenethiosulfinate). |  | Mpro | [29] |

| γ-L-Glutamyl-S-allylcysteine. |  | Mpro | [30] |

| Extracts | Concentration (μg/mL) | Max. Inhibition (%) | IC35 (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FL | 10 | 38.71 | 1.0 ± 0.38 |

| FE | 10 | 35.13 | 3.1 ± 0.62 |

| TL | 10 | 42.16 | 0.1 ± 0.03 |

| TE | 10 | 34.95 | 0.5 ± 0.06 |

| Fractions | Concentration (μg/mL) | Inhibition Max (%) | IC40 (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hexane | 100 | 48.76 | 0.09 ± 0.03 |

| Chloroform | 100 | 40.36 | 96.07 ± 35.36 |

| AcOEt | 100 | 40.78 | 0.07 ± 0.03 |

| Aqueous | 100 | 57.26 | 0.01 ± 0.005 |

| L | 2D Structures | IUPAC | Class | Molecular Formula | Exact Mass | PubChem CID | Rt (min) | m/z Experimental [M-H]- | m/z Calculated [M-H]- | Area (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

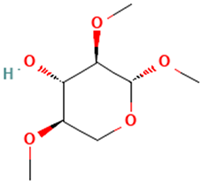

| 1 |  | Methyl 2,4-di-O-methyl-β-d-xylopyranoside | Sugars | C8H16O5 | 192.09977361 Da | 21607730 | 3.591 | 192 | 192.099 | 1.189 | PubChem CID: 21607730 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

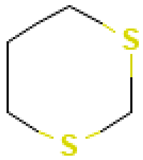

| 2 |  | 1,3-Dithiane | Sulfur compounds | C4H8S2 | 120.00674260 Da | 10451 | 5.615 | 120 | 120 | 0.519 | PubChem CID: 10451 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

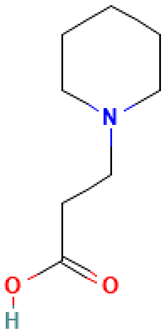

| 3 |  | 1-Piperidinepropanoic acid | Organic acids | C8H15NO2 | 157.110278721 Da | 117782 | 6.565 | 157 | 157.11 | 0.107 | PubChem CID: 117782 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

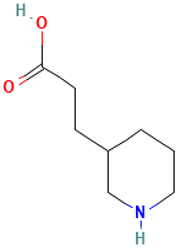

| 4 |  | 3-(Piperidin-3-yl)propanoic acid | Organic acids | C8H15NO2 | 157.110278721 Da | 5152304 | 6.6 | 157 | 157.11 | 0.124 | PubChem CID: 5152304 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

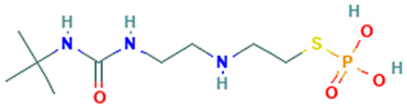

| 5 |  | N-t-Butyl-N′-2-[2-thiophosphatoethyl]aminoethylurea | Sulfur compound | C9H22N3O4PS | 299.10686436 Da | 546889 | 6.897 | 166 | 166.06 | 0.166 | PubChem CID: 546889 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

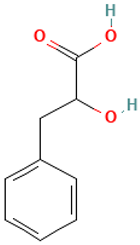

| 6 |  | DL-3-Phenyllactic acid | Organic acids | C9H10O3 | 166.062994177 Da | 3848 | 7.134 | 166 | 166.06 | 0.395 | PubChem CID: 117782 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 7 |  | 2,2-Dimethylthiazolidine | Sulfur compound | C5H11NS | 117.06122053 Da | 88015 | 7.235 | 117 | 117.06 | 0.476 | PubChem CID: 3848 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

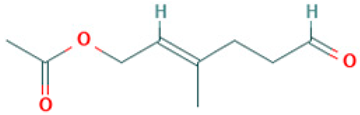

| 8 |  | Acetic acid, 3-methyl-6-oxo-hex-2-enyl ester | Esters | C9H14O3 | 170.094294304 Da | 5363568 | 7.657 | 170 | 170.09 | 1.177 | PubChem CID: 5363568 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 9 |  | 1-[N-Aziridyl]propane-2-thiol | Sulfur compounds | C5H11NS | 117.06122053 Da | 284764 | 7.959 | 117 | 117.06 | 0.852 | PubChem CID: 284764 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

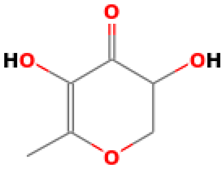

| 10 |  | 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl | Others | C6H8O4 | 144.04225873 Da | 119838 | 8.227 | 144 | 144.04 | 0.467 | PubChem CID: 119838 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 11 |  | 1-[(Trimethylsilyl)oxy]propan-2-ol | Others | C6H16O2Si | 148.091956283 Da | 23105108 | 8.494 | 148 | 148.09 | 4.749 | PubChem CID: 23105108 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

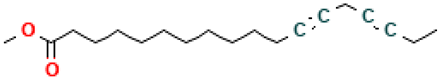

| 12 |  | 3,6-Octadecadiynoic acid, methyl ester | Esters | C19H30O2 | 294.255880323 Da | 71438608 | 10.167 | 290 | 290.22 | 1.365 | PubChem CID: 71438608 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

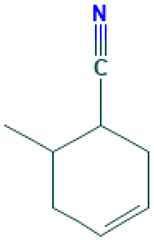

| 13 |  | 3-Cyclohexen-1-nitrile, 6-methyl | Others | C8H11N | 121.089149355 Da | 549257 | 10.547 | 121 | 121.08 | 0.409 | PubChem CID: 549257 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 14 |  | 12,15-Octadecadiynoic acid, methyl ester | Esters | C19H30O2 | 290.224580195 Da | 538453 | 10.66 | 290 | 290.22 | 0.409 | PubChem CID: 538453 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 15 |  | Diallyl disulphide | Sulfur compounds | C6H10S2 | 146.02239267 Da | 16590 | 11.918 | 146 | 146.02 | 0.589 | PubChem CID: 16590 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

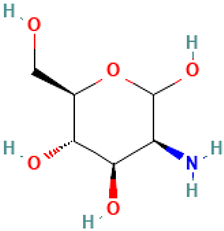

| 16 |  | Mannosamine | Others | C6H13NO5 | 179.07937252 Da | 440049 | 12.233 | 179 | 179.07 | 0.428 | PubChem CID: 440049 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 17 |  | 4-Oxatricyclo[5.2.1.0(2,6)]dec-8-ene-3,5-dione, 10,10-dimethyl-7-(trimethylsilyl) | Others | C14H20O3Si | 264.11817103 Da | 553289 | 14.732 | 264 | 264.11 | 2.308 | PubChem CID: 553289 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 18 |  | l-Gala-l-ido-octose | Sugars | C8H16O8 | 240.084517 Da | 219659 | 12.678 | 240 | 240.08 | 0.651 | PubChem CID: 219659; NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 19 |  | Trisulfide, di-2-propenyl | Sulfur compounds | C6H10S3 | 177.99446384 Da | 16315 | 13.052 | 178 | 177.99 | 0.247 | PubChem CID: 16315; NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 20 |  | Hydrocinnamic acid, o-[(1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-2-naphthyl)methyl] | Organic acids | C21H24O2 | 294.161979940 Da | 582809 | 15.948 | 294 | 294.16 | 1.503 | PubChem CID: 582934 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 21 |  | Trisulfide, methyl 2-propenyl | Sulfur compounds | C4H8S3 | 151.97881378 Da | 61926 | 13.936 | 152 | 151.97 | 3.861 | PubChem CID: 135403803 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

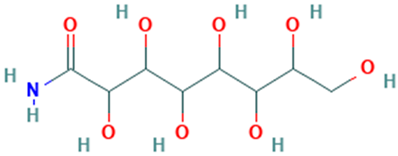

| 22 |  | d-Gala-l-ido-octonic amide | Others | C8H17NO8 | 255.09541650 Da | 552061 | 20.133 | 255 | 255.09 | 0.521 | PubChem CID: 552061NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

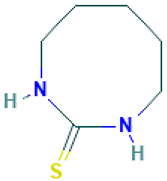

| 23 |  | 1,3-Diazacyclooctane-2-thione | Sulfur compounds | C6H12N2S | 144.07211956 Da | 5372734 | 14.465 | 144 | 144.07 | 2.114 | PubChem CID: 5372734 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

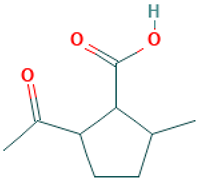

| 24 |  | Cyclopentanecarboxylic acid, 2-acetyl-5-methyl- | Organic acids | C9H14O3 | 170.094294304 Da | 538095 | 12.447 | 170 | 170.09 | 0.572 | PubChem CID: 440049; NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 25 |  | 4-Methyl(trimethylene)silyloxyoctane | Others | C12H26OSi | 214.175291983 Da | 588574 | 15.153 | 214 | 214.17 | 2.522 | PubChem CID: 588574 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 26 |  | 1-Methyl-1-n-octyloxy-1-silacyclobutane | Others | C12H26OSi | 214.175291983 Da | 598585 | 15.414 | 214 | 214.17 | 2.076 | PubChem CID: 598585NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

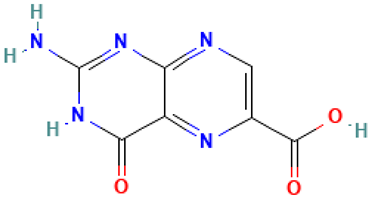

| 27 |  | Pterin-6-carboxylic acid | Organic acids | C7H5N5O3 | 207.03923904 Da | 135403803 | 13.408 | 207 | 207.03 | 0.182 | PubChem CID: 61926 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

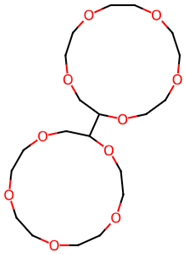

| 28 |  | (2S,2′S)-2,2′-Bis[1,4,7,10,13-pentaoxacyclopentadecane] | Others | C20H38O10 | 438.24649740 Da | 552595 | 16.026 | 438 | 438.24 | 1.712 | PubChem CID: 552595 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

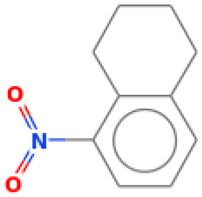

| 29 |  | Naphthalene, 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-5-nitro | Others | C10H11NO2 | 177.078978594 Da | 93130 | 16.405 | 177 | 177.07 | 2.55 | PubChem CID: 93130 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 30 |  | 3,7,11,14,18-Pentaoxa-2,19-disilaeicosane, 2,2,19,19-tetramethyl- | Others | C17H40O5Si2 | 380.24142744 Da | 552943 | 16.904 | 380 | 380.24 | 3.723 | PubChem CID: 552943 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

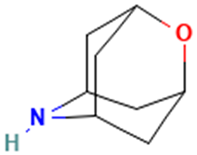

| 31 |  | 2-Oxa-6-azatricyclo [3.3.1.1(3,7)]decane | Others | C8H13NO | 139.099714038 Da | 586977 | 17.587 | 139 | 139.09 | 1.602 | PubChem CID: 586977 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 32 |  | 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid, 2-[(trimethylsilyl)oxy]-1-[[(trimethylsilyl)oxy]methyl]ethyl ester, (Z,Z,Z)- | Esters | C27H52O4Si2 | 496.34041320 Da | 5362857 | 17.925 | 496 | 496.3 | 0.621 | PubChem CID: 5362857 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

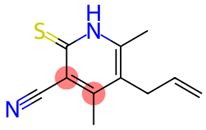

| 33 |  | Pyridine-3-carbonitrile, 5-allyl-4,6-dimeethyl-2-mercapto- | Sulfur compounds | C11H12N2S | 204.07211956 Da | 657927 | 18.079 | 204 | 204.07 | 0.622 | PubChem CID: 657927 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 34 |  | Acetamide, N-methyl-N-[4-(3-hydroxypyrrolidinyl)-2-butynyl]- | Others | C11H18N2O2 | 210.136827821 Da | 536669 | 18.88 | 210 | 210.13 | 0.604 | PubChem CID: 536669 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

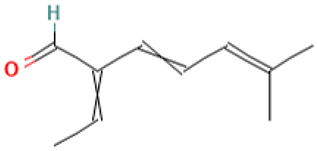

| 35 |  | 3,5-Heptadienal, 2-ethylidene-6-methyl- | Others | C10H14O | 150.104465066 Da | 572127 | 19.717 | 150 | 150.1 | 1.569 | PubChem CID: 572127 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

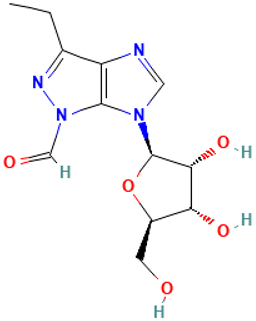

| 36 |  | Pyrazole[4,5-b]imidazole, 1-formyl-3-ethyl-6-β-d-ribofuranosyl- | Others | C12H16N4O5 | 296.11206962 Da | 91692119 | 14.612 | 296 | 296.11 | 1.547 | PubChem CID: 91692119 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 37 |  | L-Glucose | Sugars | C6H12O6 | 180.06338810 Da | 2724488 | 20.441 | 180 | 180.06 | 0.512 | PubChem CID: 2724488 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

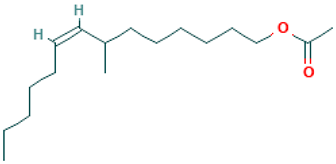

| 38 |  | 7-Methyl-Z-tetradecen-1-ol acetate | Esters | C17H32O2 | 268.240230259 Da | 5363222 | 20.744 | 268 | 268.24 | 0.451 | PubChem CID: 5363222 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

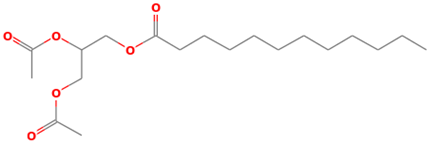

| 39 |  | Dodecanoic acid, 2,3-bis(acetyloxy)propyl ester | Esters | C19H34O6 | 358.23553880 Da | 169212 | 21.462 | 358 | 358.23 | 2.143 | PubChem CID: 169212 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

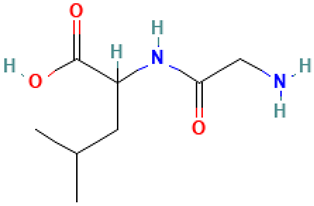

| 40 |  | DL-Leucine, N-[2-(chloroimino)-1-oxopropyl] | Amino acid | C9H15ClN2O3 | 234.0771200 Da | 9603629 | 21.694 | 234 | 234.07 | 1.39 | PubChem CID: 9603629 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

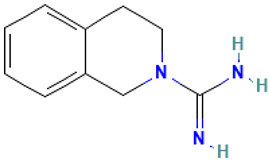

| 41 |  | 2(1H)-Isoquinolinecarboximidamide, 3,4-dihydro- | Others | C10H13N3 | 175.110947427 Da | 2966 | 21.996 | 175 | 175.11 | 2.246 | PubChem CID: 2966 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

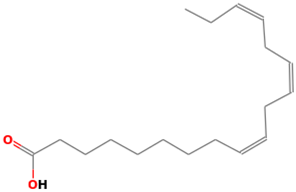

| 42 |  | 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid | Organic acids | C18H30O2 | 278.224580195 Da | 88801875 | 22.186 | 278 | 278.42 | 2.472 | PubChem CID: 88801875 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

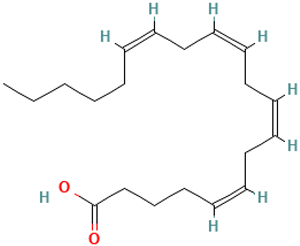

| 43 |  | Arachidonic acid | Organic acids | C20H32O2 | 304.240230259 Da | 444899 | 22.685 | 304 | 304.46 | 1.984 | PubChem CID: 444899 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 44 |  | 2-Nonenoic acid, 9-(dimethylamino)-7-hydroxy-2-methyl-9-oxo-, methyl ester | Esters | C13H23NO4 | 257.16270821 Da | 5364160 | 23 | 257 | 257.16 | 1.579 | PubChem CID: 5364160 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 45 |  | DL-Leucine, N-glycyl | Amino acid | C8H16N2O3 | 188.11609238 Da | 102468 | 23.409 | 188 | 188.11 | 4.755 | PubChem CID: 102468 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 46 |  | 1-S-[(1E)-N-Hydroxy-2-(1H-indol-3-yl)ethanimidoyl]-1-thiohexopyranose | Sulfur compounds | C16H20N2O6S | 368.10420754 Da | 9603283 | 23.86 | 368 | 368.1 | 1.128 | PubChem CID: 9603283 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 47 |  | Benzocycloheptano[2,3,4-I,j]isoquinoline, 4,5,6,6a-tetrahydro-1,9-dihydroxy-2,10-dimethoxy-5-methyl | Alkaloid | C20H23NO4 | 341.16270821 Da | 339326 | 24.014 | 341 | 341.16 | 0.964 | PubChem CID: 339326 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 48 |  | Desulphosinigrin | Sulfur compounds | C10H17NO6S | 279.07765844 Da | 9601716 | 25.041 | 279 | 279.07 | 1.055 | PubChem CID: 9601716 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 49 |  | Linoleic acid ethyl ester | Esters | C20H36O2 | 308.271530387 Da | 5282184 | 25.386 | 308 | 308.27 | 3.485 | PubChem CID: 5282184 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 50 |  | (+-)-5-(1-Acetoxy-1-methylethyl)-2-methyl-2-cyclohexen-1-one semicarbazone | Others | C13H21N3O3 | 267.15829154 Da | 9603716 | 25.932 | 267 | 267.15 | 3.594 | PubChem CID: 9603716 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 51 |  | 2(3H)-Naphthalenone, 4,4a,5,6,7,8-hexahydro-1-methoxy | Others | C11H16O | 180.115029749 Da | 534313 | 27.059 | 180 | 180.11 | 3.659 | PubChem CID: 534313 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

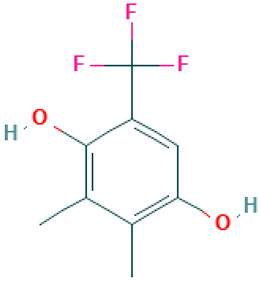

| 52 |  | Phen-1,4-diol, 2,3-dimethyl-5-trifluoromethyl | Others | C9H9F3O2 | 206.05546401 Da | 590850 | 27.558 | 206 | 206.05 | 2.824 | PubChem CID: 590850 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

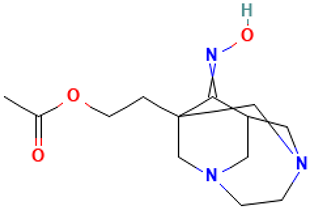

| 53 |  | 1-(2-Acetoxyethyl)-3,6-diazahomoadamantan-9-one oxime | Others | C13H21N3O3 | 267.15829154 Da | 551906 | 28.561 | 267 | 267.15 | 4.072 | PubChem CID: 551906 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

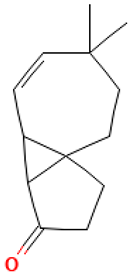

| 54 |  | Cyclopenta[1,3]cyclopropa[1,2]cyclohepten-3(3aH)-one, 1,2,3b,6,7,8-hexahydro-6,6-dimethyl | Others | C13H18O | 190.135765193 Da | 561869 | 30.946 | 190 | 190.13 | 2.99 | PubChem CID: 561869 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| 55 |  | Heptaethylene glycol monododecyl ether | Others | C26H54O8 | 494.38186868 Da | 76459 | 31.653 | 494 | 494.38 | 3.487 | PubChem CID: 76459 NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center |

| Compound | Antiviral Activity | Other Relevant Activities |

|---|---|---|

| L41: 2(1H)-Isoquinolinecarboximidamide, 3,4-dihydro- (Debrisoquine) | TMPRSS2 inhibitor [35] | Antihypertensive [36] |

| L42: 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid (α-Linolenic acid) | Interrupts the binding, adsorption, and entry stages of Zika virus replication cycle [37] | Anti-obesity, antidiabetic, cardiovascular-protective, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, neuroprotection, and antibacterial [38,39] Anti-hypercholesterolemic [40] |

| L3: 1-Piperidinepropanoic acid | Not reported | Anti-inflammatory [41,42] |

| L6: DL-3-Phenyllactic acid | Not reported | Antibacterial, antibiofilm, and antifungal [43,44] |

| L10: 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl- | Not reported | Antioxidant [45,46,47] |

| L15: Diallyl disulphide (DADS) | Not reported | Anticancer [48] Cardioprotective, antihypertensive, antibacterial, antiparasitic, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory [49] |

| L16: Mannosamine | Not reported | Dextransucrase inhibition [50] Cytotoxic effects with free fatty acids [51] |

| L19: Trisulfide, di-2-propenyl (Diallyl trisulfide or DATS) | Not reported | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antitumor, cardioprotective, and immunomodulatory [48,52,53,54,55,56] |

| L21: Trisulfide, methyl 2-propenyl (MATS) | Not reported | Antiplatelet [57,58] |

| L43: Arachidonic acid | Not reported | Tumoricidal [59] |

| L47: Benzocycloheptano[2,3,4-I,j]isoquinoline, 4,5,6,6a-tetrahydro-1,9-dihydroxy-2,10-dimethoxy-5-methyl | Not reported | Antidiabetic potential [60] |

| L49: Linoleic acid ethyl ester (Ethyl Linoleate) | Not reported | Anti-inflammatory [61] Melanogenesis inhibitor [62,63] |

| Compounds | L36 | L20 | L17 |

|---|---|---|---|

| MW | 368.4 | 294.39 | 264.39 |

| H-bond acceptors | 7 | 2 | 3 |

| H-bond donors | 6 | 1 | 0 |

| iLOGP | 1.33 | 2.73 | 2.49 |

| XLOGP3 | 0.5 | 4.73 | 3.15 |

| Consensus Log P | 0.18 | 4.14 | 2.49 |

| Ali Log S | −3.51 | −5.24 | −3.73 |

| Ali class | Soluble | Moderately soluble | Soluble |

| GI absorption | Low | High | High |

| BBB permeant | No | Yes | Yes |

| Pgp substrate | No | No | No |

| CYP1A2 inhibitor | Yes | No | No |

| CYP2C19 inhibitor | No | No | No |

| CYP2C9 inhibitor | No | Yes | No |

| CYP2D6 inhibitor | No | Yes | No |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor | No | No | No |

| log Kp (cm/s) | −8.19 | −4.74 | −5.68 |

| Lipinski violations | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ghose violations | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Veber violations | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Egan violations | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Muegge violations | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Bioavailability score | 0.55 | 0.85 | 0.55 |

| PAINS | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Brenk | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Leadlikeness violations | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Synthetic accessibility | 4.88 | 2.77 | 4.91 |

| Target | L36 | L20 | L17 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatotoxicity | Inactive (0.55) | Inactive (0.51) | Inactive (0.72) |

| Neurotoxicity | Inactive (0.72) | Inactive (0.61) | Inactive (0.70) |

| Nephrotoxicity | Active (0.57) | Active (0.54) | Inactive (0.59) |

| Respiratory toxicity | Active (0.74) | Active (0.62) | Active (0.67) |

| Cardiotoxicity | Inactive (0.60) | Inactive (0.57) | Inactive (0.83) |

| Carcinogenicity | Inactive (0.51) | Inactive (0.68) | Inactive (0.60) |

| Immunotoxicity | Inactive (0.98) | Inactive (0.99) | Inactive (0.98) |

| Mutagenicity | Active (0.50) | Inactive (0.66) | Inactive (0.64) |

| Cytotoxicity | Inactive (0.69) | Inactive (0.83) | Inactive (0.79) |

| BBB barrier | Active (0.59) | Active (0.81) | Active (0.89) |

| Ecotoxicity | Inactive (0.59) | Active (0.57) | Active (0.59) |

| Clinical toxicity | Inactive (0.52) | Inactive (0.55) | Inactive (0.56) |

| Nutritional toxicity | Inactive (0.58) | Inactive (0.65) | Inactive (0.54) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Delgado, M.S.; Herrera-Rodulfo, A.F.; Reyes-Melo, K.Y.; Mohan, A.; Góngora-Rivera, F.; Pedroza-Flores, J.A.; Paz-González, A.D.; Rivera, G.; Camacho-Corona, M.d.R.; Carrillo-Tripp, M. Garlic-Derived Phytochemical Candidates Predicted to Disrupt SARS-CoV-2 RBD–ACE2 Binding and Inhibit Viral Entry. Molecules 2025, 30, 4616. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234616

García-Delgado MS, Herrera-Rodulfo AF, Reyes-Melo KY, Mohan A, Góngora-Rivera F, Pedroza-Flores JA, Paz-González AD, Rivera G, Camacho-Corona MdR, Carrillo-Tripp M. Garlic-Derived Phytochemical Candidates Predicted to Disrupt SARS-CoV-2 RBD–ACE2 Binding and Inhibit Viral Entry. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4616. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234616

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Delgado, Martha Susana, Aldo Fernando Herrera-Rodulfo, Karen Y. Reyes-Melo, Ashly Mohan, Fernando Góngora-Rivera, Jesús Andrés Pedroza-Flores, Alma D. Paz-González, Gildardo Rivera, María del Rayo Camacho-Corona, and Mauricio Carrillo-Tripp. 2025. "Garlic-Derived Phytochemical Candidates Predicted to Disrupt SARS-CoV-2 RBD–ACE2 Binding and Inhibit Viral Entry" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4616. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234616

APA StyleGarcía-Delgado, M. S., Herrera-Rodulfo, A. F., Reyes-Melo, K. Y., Mohan, A., Góngora-Rivera, F., Pedroza-Flores, J. A., Paz-González, A. D., Rivera, G., Camacho-Corona, M. d. R., & Carrillo-Tripp, M. (2025). Garlic-Derived Phytochemical Candidates Predicted to Disrupt SARS-CoV-2 RBD–ACE2 Binding and Inhibit Viral Entry. Molecules, 30(23), 4616. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234616