Protective Effects of Neutral Lipids from Phaeodactylum tricornutum on Palmitate-Induced Lipid Accumulation in HepG2 Cells: An In Vitro Model of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Fatty Acid (FA) Composition of Neutral (NL) and Polar Lipid (PL) Extracts from P. tricornutum

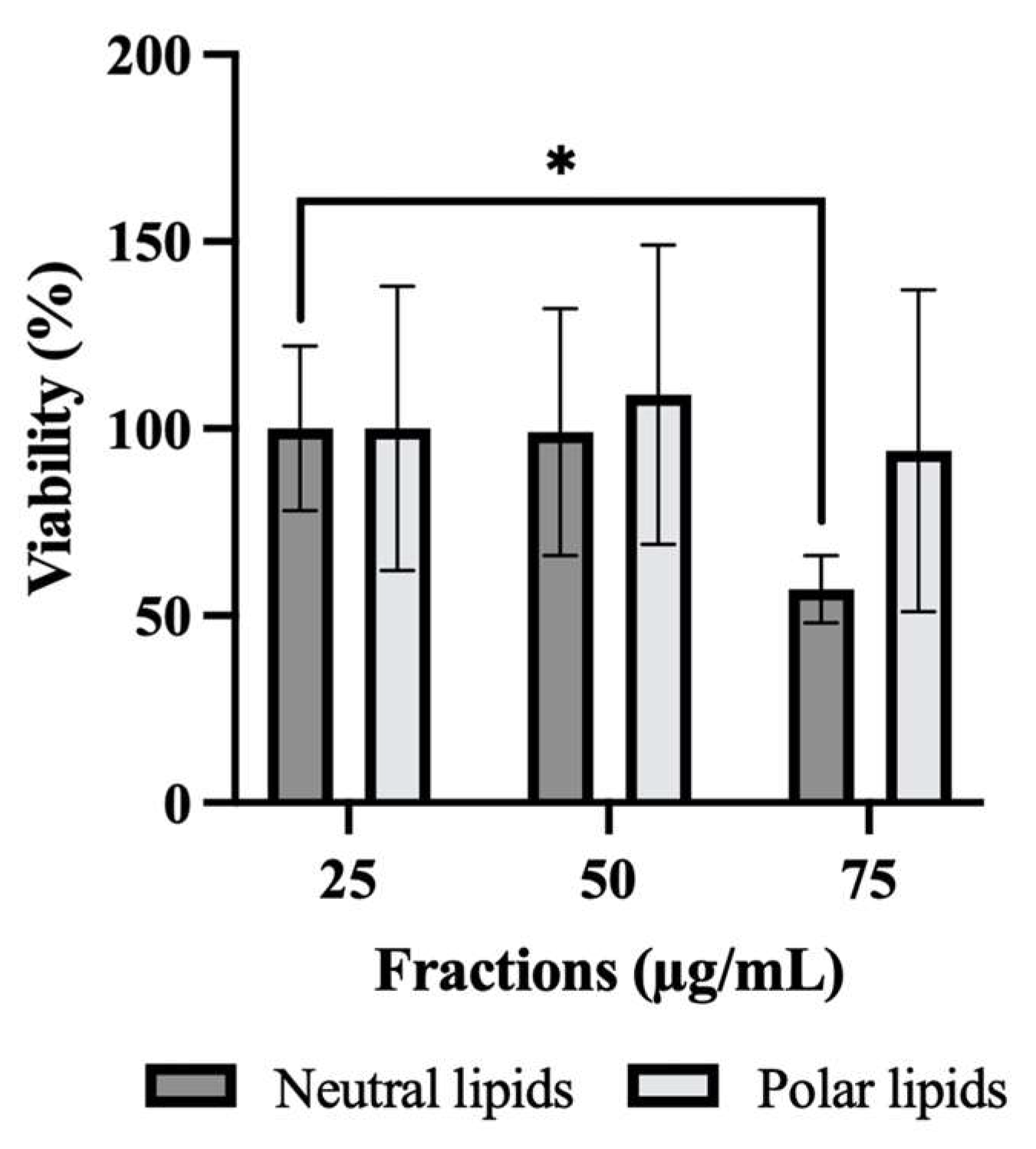

2.2. Effect of Neutral and Polar Lipids from P. tricornutum on HepG2 Cell Viability

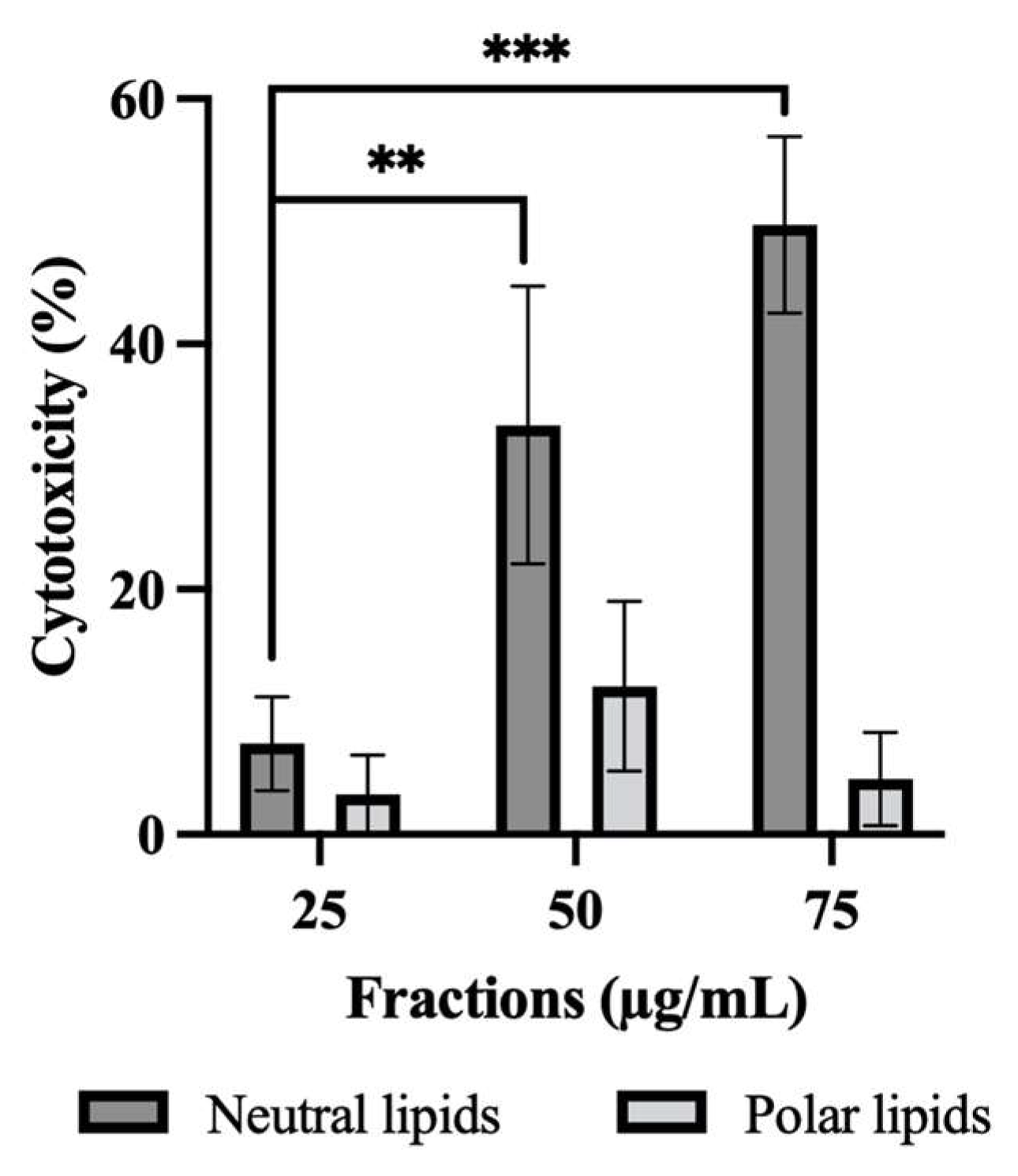

2.3. Effect of Neutral and Polar Lipids on HepG2 Cell Cytotoxicity

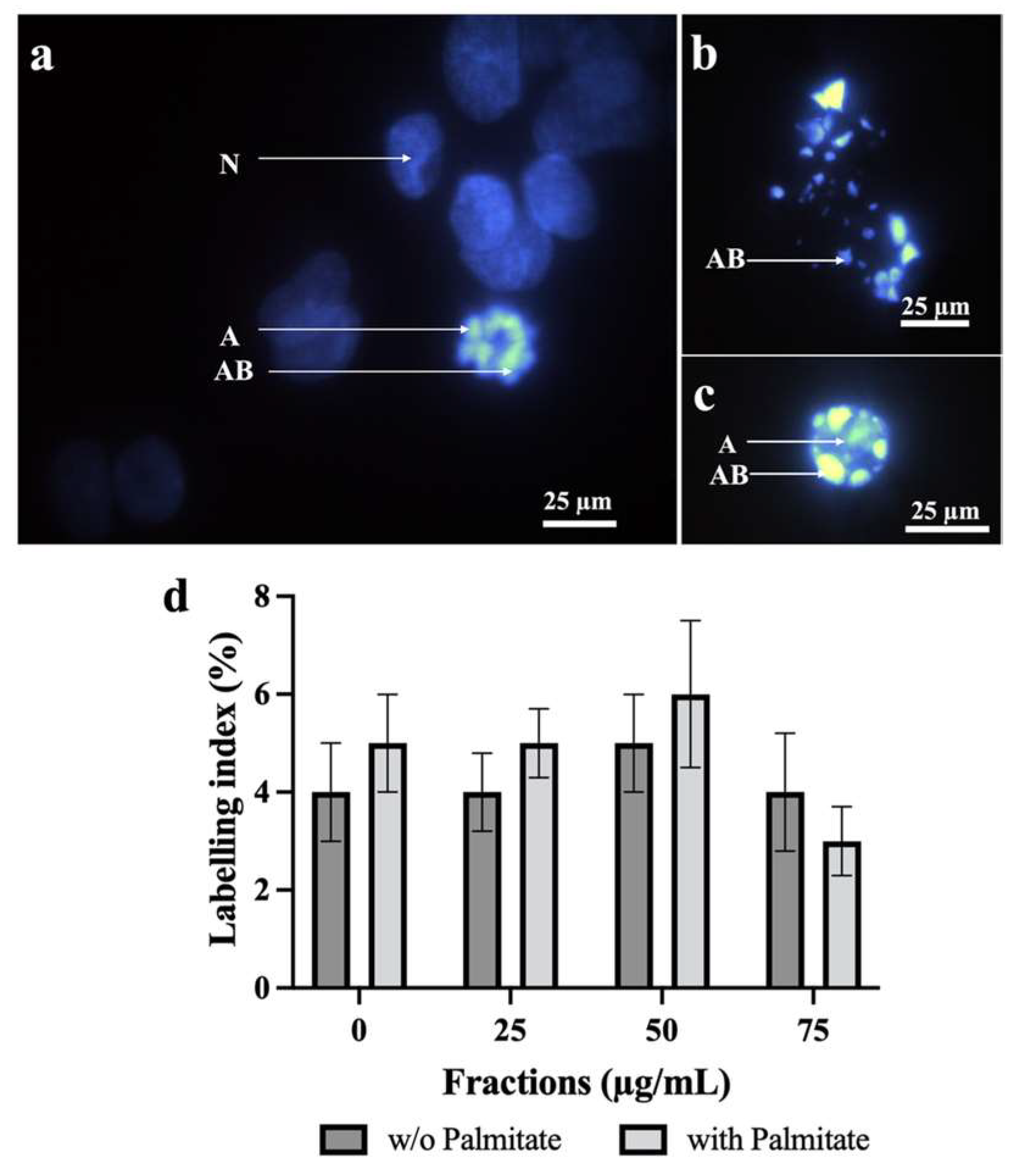

2.4. Effect of Neutral Lipids from P. tricornutum on HepG2 Apoptosis

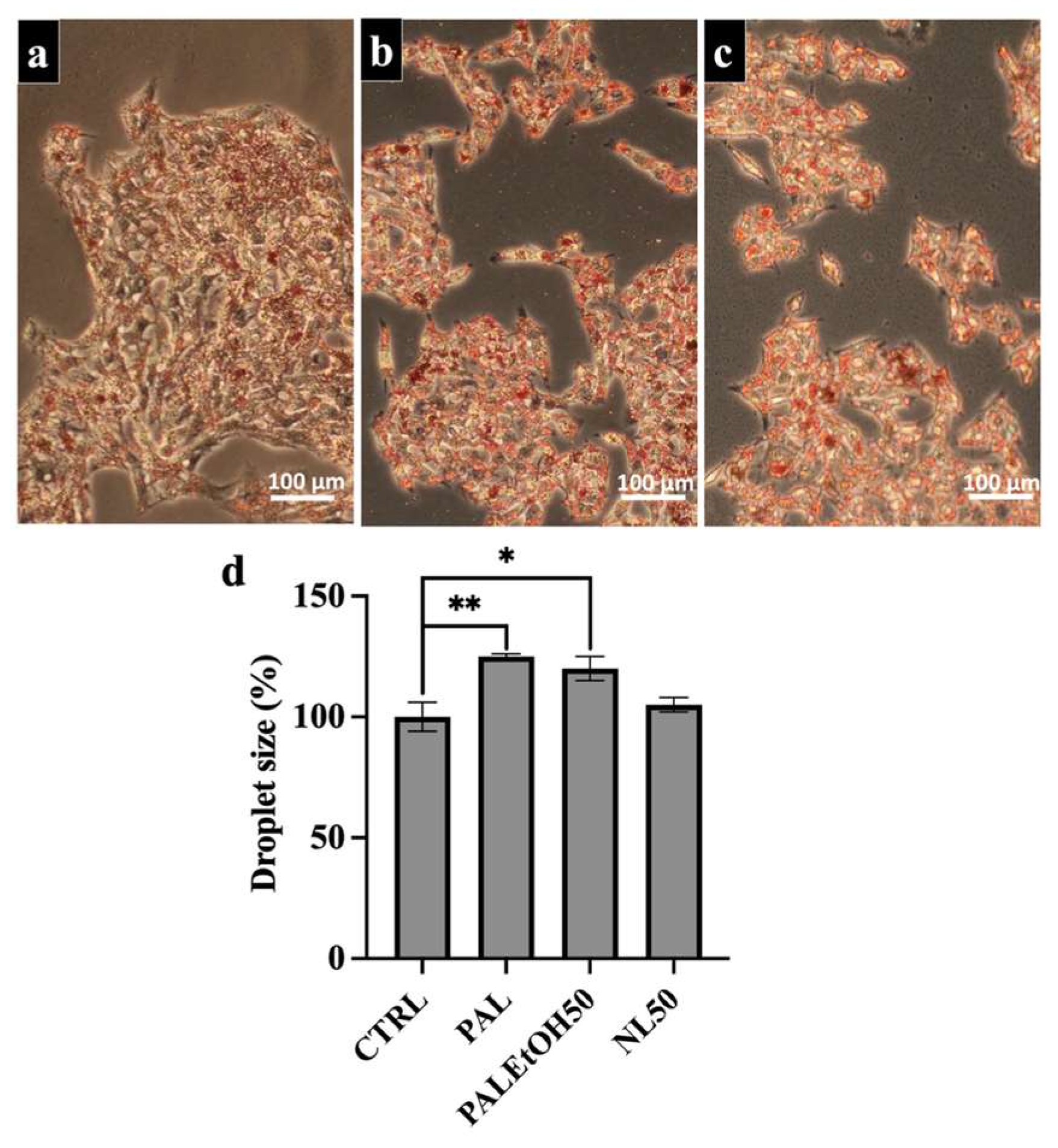

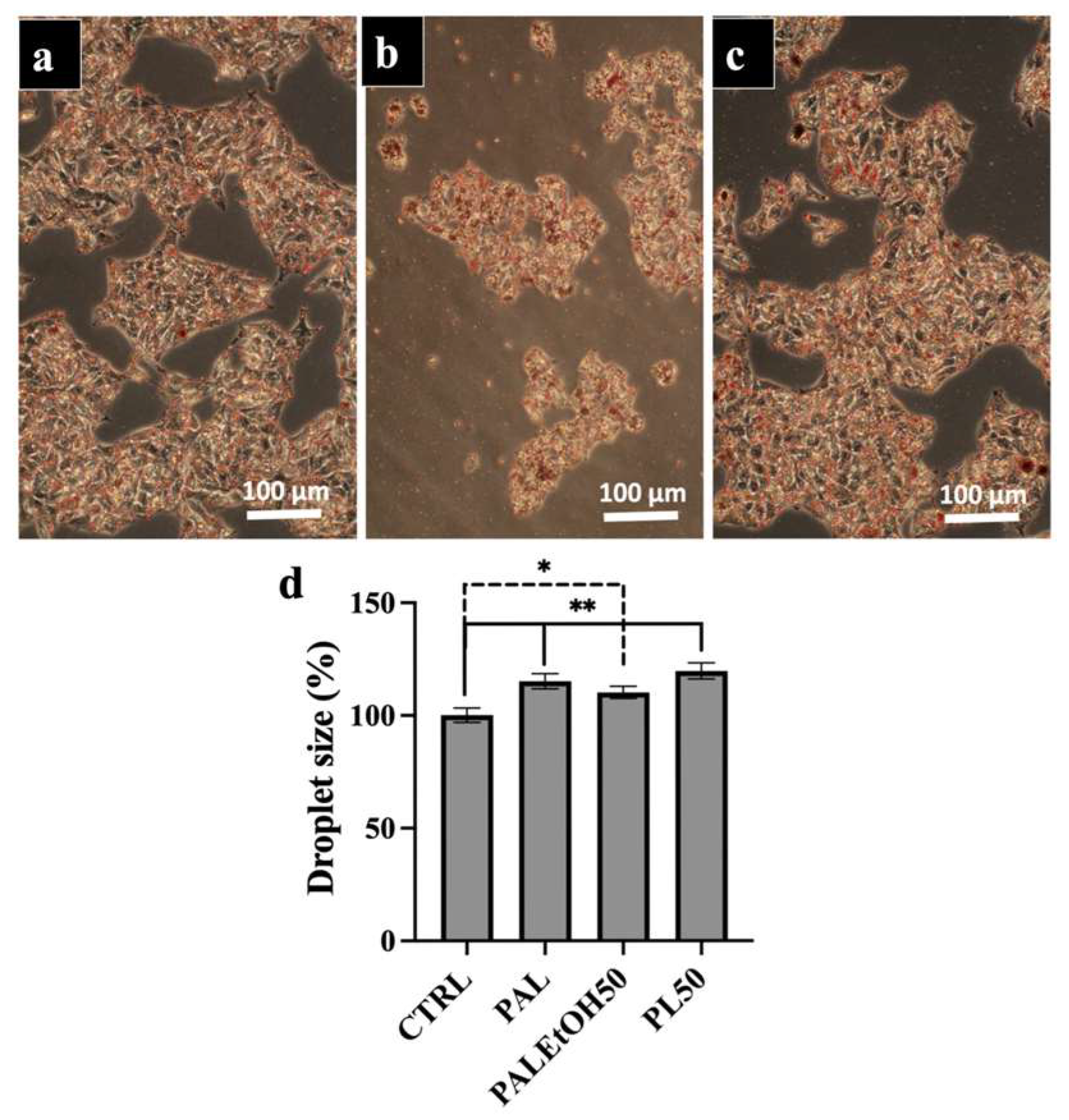

2.5. Effect of NL and PL at a Concentration of 50 µg/mL (NL50 and PL50) on Lipid Droplet Size in HepG2 Cells

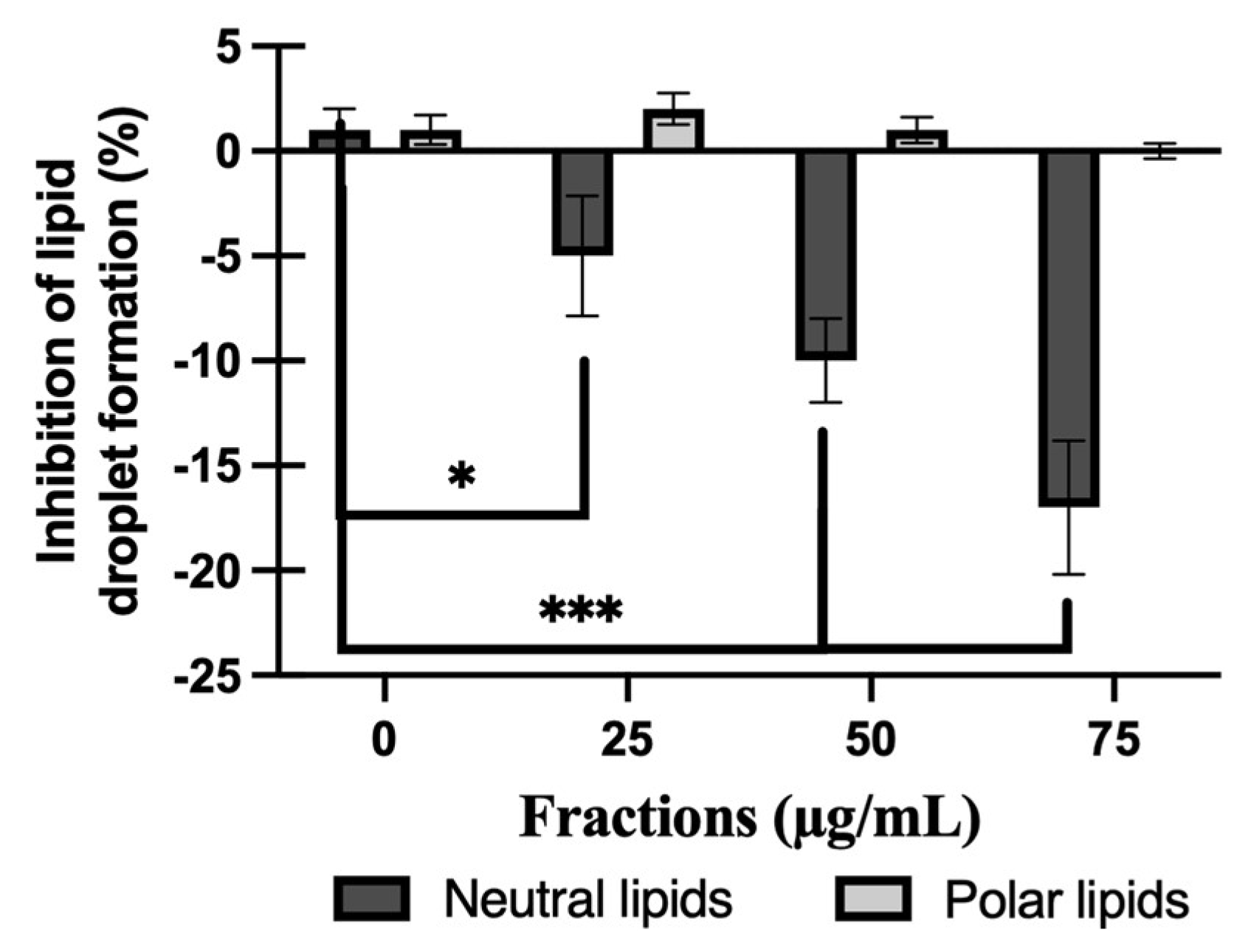

2.6. Effect of NL or PL Fractions on Lipid Droplet Accumulation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.1.1. Human Hepatocyte Model

4.1.2. P. tricornutum Lipid Extracts

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Cell Culture of HepG2

4.2.2. NL and PL Extracts from P. tricornutum

4.2.3. HepG2 Proliferation Assay of Neutral and Polar Lipid Extracts of P. tricornutum Using MTT Method

4.2.4. HepG2 Cytotoxicity Assay of NL and PL Extracts of P. tricornutum Using the Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Assay Kit

4.2.5. Hoechst Staining on HepG2 Nuclei with or Without NL Extracts

4.2.6. Palmitate-Treated HepG2 and Oil Red Staining with or Without NL and PL Fractions

4.3. Statistics

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meldrum, D.R.; Morris, M.A.; Gambone, J.C. Obesity Pandemic: Causes, Consequences, and Solutions—But Do We Have the Will? Fertil. Steril. 2017, 107, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Atlas of EHealth Country Profiles: The Use of EHealth in Support of Universal Health Coverage: Based on the Findings of the Third Global Survery on EHealth 2015; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-92-4-156521-9.

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Trends in Adult Body-Mass Index in 200 Countries from 1975 to 2014: A Pooled Analysis of 1698 Population-Based Measurement Studies with 19·2 Million Participants. Lancet 2016, 387, 1377–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeda-Valdes, P.; Aguilar-Olivos, N.; Uribe, M.; Mendez-Sanchez, N. Common Features of the Metabolic Syndrome and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Rev. Recent Clin. Trials 2014, 9, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cusi, K. Role of Obesity and Lipotoxicity in the Development of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: Pathophysiology and Clinical Implications. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 711–725.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyendyk, J.P.; Guo, G.L. Steatosis DeLIVERs High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 1714–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun Kim, M.; Kung, S.; Grewal, T.; D. Roufogalis, B. Methodologies for Investigating Natural Medicines for the Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD). Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2012, 13, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, C.D.; Targher, G. NAFLD: A Multisystem Disease. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, S47–S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, C.; Côme, M.; Blanckaert, V.; Chini Zittelli, G.; Faraloni, C.; Nazih, H.; Ouguerram, K.; Mimouni, V.; Chénais, B. Effect of Carotenoids from Phaeodactylum Tricornutum on Palmitate-Treated HepG2 Cells. Molecules 2020, 25, 2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, C.; Côme, M.; Ulmann, L.; Chini Zittelli, G.; Faraloni, C.; Nazih, H.; Ouguerram, K.; Chénais, B.; Mimouni, V. Preventive Effects of the Marine Microalga Phaeodactylum Tricornutum, Used as a Food Supplement, on Risk Factors Associated with Metabolic Syndrome in Wistar Rats. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, J.; Park, S.; Choi, Y.; Kim, H. Cell Cycle Synchronization by Serum Starvation. Cells 2020, 9, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, E.; Figueroa, S.; Oset-Gasque, M.J.; González, M.P. Apoptosis and Necrosis: Two Distinct Events Induced by Cadmium in Cortical Neurons in Culture. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 138, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, F.K.-M.; Moriwaki, K.; De Rosa, M.J. Detection of Necrosis by Release of Lactate Dehydrogenase Activity. In Immune Homeostasis: Methods and Protocols; Snow, A.L., Lenardo, M.J., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 65–70. ISBN 978-1-62703-290-2. [Google Scholar]

- Youn, Y.; Kim, Y.-S. Inhibitory Effects of Citrus Unshiu Pericarpium Extracts on Palmitate-Induced Lipotoxicity in HepG2 Cells. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 25, 1709–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jump, D.B.; Lytle, K.A.; Depner, C.M.; Tripathy, S. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids as a Treatment Strategy for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 181, 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Lechón, M.J.; Donato, M.T.; Martínez-Romero, A.; Jiménez, N.; Castell, J.V.; O’Connor, J.-E. A Human Hepatocellular in Vitro Model to Investigate Steatosis. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2007, 165, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavez-Tapia, N.C.; Rosso, N.; Tiribelli, C. Effect of Intracellular Lipid Accumulation in a New Model of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyzos, S.A.; Kountouras, J.; Mantzoros, C.S. Obesity and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: From Pathophysiology to Therapeutics. Metabolism 2019, 92, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehlem, A.; Hagberg, C.E.; Muhl, L.; Eriksson, U.; Falkevall, A. Imaging of Neutral Lipids by Oil Red O for Analyzing the Metabolic Status in Health and Disease. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 1149–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiels, K.; Tsoupras, A.; Lordan, R.; Nasopoulou, C.; Zabetakis, I.; Murray, P.; Saha, S.K. Bioactive Lipids of Marine Microalga Chlorococcum sp. SABC 012504 with Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Thrombotic Activities. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regueiras, A.; Huguet, Á.; Conde, T.; Couto, D.; Domingues, P.; Domingues, M.R.; Costa, A.M.; Silva, J.L.D.; Vasconcelos, V.; Urbatzka, R. Potential Anti-Obesity, Anti-Steatosis, and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Extracts from the Microalgae Chlorella Vulgaris and Chlorococcum Amblystomatis under Different Growth Conditions. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Mentec, H.; Monniez, E.; Legrand, A.; Monvoisin, C.; Lagadic-Gossmann, D.; Podechard, N. A New In Vivo Zebrafish Bioassay Evaluating Liver Steatosis Identifies DDE as a Steatogenic Endocrine Disruptor, Partly through SCD1 Regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albracht-Schulte, K.; Gonzalez, S.; Jackson, A.; Wilson, S.; Ramalingam, L.; Kalupahana, N.S.; Moustaid-Moussa, N. Eicosapentaenoic Acid Improves Hepatic Metabolism and Reduces Inflammation Independent of Obesity in High-Fat-Fed Mice and in HepG2 Cells. Nutrients 2019, 11, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, D.; Brevik-Andersen, M.; Qin, Y.; Innes, J.K.; Calder, P.C. Evaluation of a High Concentrate Omega-3 for Correcting the Omega-3 Fatty Acid Nutritional Deficiency in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (CONDIN). Nutrients 2018, 10, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spooner, M.H.; Jump, D.B. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Adults and Children: Where Do We Stand? Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2019, 22, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Yue, H.; Jia, M.; Liu, W.; Qiu, B.; Hou, H.; Huang, F.; Xu, T. Effect of Low-Ratio n-6/n-3 PUFA on Blood Glucose: A Meta-Analysis. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 4557–4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, S.; Pu, S.; Jones, P.J. Current Evidence Supporting the Link Between Dietary Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Disease. Lipids 2016, 51, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela, R.; Videla, L.A. The Importance of the Long-Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid n-6/n-3 Ratio in Development of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Associated with Obesity. Food Funct. 2011, 2, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, L.; Rosqvist, F.; Parry, S.A. The Influence of Dietary Fatty Acids on Liver Fat Content and Metabolism. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2020, 79, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listenberger, L.L.; Han, X.; Lewis, S.E.; Cases, S.; Farese, R.V.; Ory, D.S.; Schaffer, J.E. Triglyceride Accumulation Protects against Fatty Acid-Induced Lipotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 3077–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-F.; Xi, Q.-H.; Sheng, Y.; Wang, Y.-M.; Wang, W.-Y.; Chi, C.-F.; Wang, B. Antioxidant Peptides from Monkfish Swim Bladders: Ameliorating NAFLD In Vitro by Suppressing Lipid Accumulation and Oxidative Stress via Regulating AMPK/Nrf2 Pathway. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadizadeh, F.; Faghihimani, E.; Adibi, P. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Diagnostic Biomarkers. World J. Gastrointest. Pathophysiol. 2017, 8, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, M.J.; Bandiera, L.; Menolascina, F.; Fallowfield, J.A. In Vitro Models for Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Emerging Platforms and Their Applications. iScience 2022, 25, 103549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, M.T.; Tolosa, L.; Gómez-Lechón, M.J. Culture and Functional Characterization of Human Hepatoma HepG2 Cells. In: Protocols in In Vitro Hepatocyte Research. Methods Mol Biol. 2015, 1250, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillard, R.R.L.; Ryther, J.H. Studies of Marine Planktonic Diatoms: I. Cyclotella Nana Hustedt, and Detonula Confervacea (Cleve) Gran. Can. J. Microbiol. 1962, 8, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Sloane Stanley, G.H. A Simple Method for the Isolation and Purification of Total Lipides from Animal Tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957, 226, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juaneda, P.; Rocquelin, G. Rapid and Convenient Separation of Phospholipids and Non Phosphorus Lipids from Rat Heart Using Silica Cartridges. Lipids 1985, 20, 40–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, W.R.; Smith, L.M. Preparation of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters and Dimethylacetals from Lipids with Boron Fluoride–Methanol. J. Lipid Res. 1964, 5, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fatty Acids | Neutral Lipids | Polar Lipids | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | ± sd | % | mean | ± sd | % | |

| C14:0 | 94.167 | 69.954 | 4.15 | 40.333 | 29.670 | 4.87 |

| C16:0 | 201.556 | 127.816 | 8.89 | 137.500 | 111.594 | 16.62 |

| C16:1n-13tr? | 61.944 | 36.781 | 2.73 | nd | nd | nd |

| C16:1n-7 | 322.444 | 211.536 | 14.22 | 92.500 | 69.168 | 11.18 |

| C16:2n-4 | 80.167 | 53.484 | 3.54 | 31.667 | 24.861 | 3.83 |

| C16:3n-4 | 228.056 | 141.334 | 10.06 | 81.167 | 70.612 | 9.81 |

| C18:0 | 27.222 | 14.849 | 1.20 | 18.500 | 23.468 | 2.24 |

| C18:1n-9 (cis+trans) | 30.056 | 17.113 | 1.33 | 21.000 | 18.520 | 2.54 |

| C18:1n-7 | nd | nd | nd | 21.333 | 20.033 | 2.58 |

| C18:2n-6cis | 38.278 | 25.088 | 1.69 | 24.333 | 21.180 | 2.94 |

| C20:4n-6 | 51.778 | 36.257 | 2.28 | 18.000 | 11.533 | 2.18 |

| C20:4n-3 | nd | nd | nd | 10.000 | 9.179 | 1.21 |

| C20:5n-3 | 922.611 | 626.803 | 40.69 | 179.333 | 94.028 | 21.67 |

| C24:0 | 29.167 | 26.704 | 1.29 | 68.000 | 65.294 | 8.22 |

| C22:6n-3 | 36.667 | 22.205 | 1.62 | 27.500 | 25.821 | 3.32 |

| SFA | 382.278 | 258.897 | 16.86 | 285.500 | 249.474 | 34.50 |

| MUFA | 451.333 | 289.632 | 19.90 | 139.333 | 112.539 | 16.84 |

| PUFA | 1433.722 | 952.043 | 63.23 | 402.667 | 284.136 | 48.66 |

| n-3 PUFA | 1003.833 | 676.255 | 44.27 | 229.833 | 139.764 | 27.77 |

| n-6 PUFA | 113.000 | 76.151 | 4.98 | 58.333 | 47.933 | 7.05 |

| n-4 PUFA | 310.111 | 195.580 | 13.68 | 113.000 | 95.821 | 13.66 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Peyras, M.; Orhant, R.-M.; Parisi, G.; Faraloni, C.; Chini Zittelli, G.; Blanckaert, V.; Mimouni, V. Protective Effects of Neutral Lipids from Phaeodactylum tricornutum on Palmitate-Induced Lipid Accumulation in HepG2 Cells: An In Vitro Model of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Molecules 2026, 31, 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020323

Peyras M, Orhant R-M, Parisi G, Faraloni C, Chini Zittelli G, Blanckaert V, Mimouni V. Protective Effects of Neutral Lipids from Phaeodactylum tricornutum on Palmitate-Induced Lipid Accumulation in HepG2 Cells: An In Vitro Model of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Molecules. 2026; 31(2):323. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020323

Chicago/Turabian StylePeyras, Marion, Rose-Marie Orhant, Giuliana Parisi, Cecilia Faraloni, Graziella Chini Zittelli, Vincent Blanckaert, and Virginie Mimouni. 2026. "Protective Effects of Neutral Lipids from Phaeodactylum tricornutum on Palmitate-Induced Lipid Accumulation in HepG2 Cells: An In Vitro Model of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease" Molecules 31, no. 2: 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020323

APA StylePeyras, M., Orhant, R.-M., Parisi, G., Faraloni, C., Chini Zittelli, G., Blanckaert, V., & Mimouni, V. (2026). Protective Effects of Neutral Lipids from Phaeodactylum tricornutum on Palmitate-Induced Lipid Accumulation in HepG2 Cells: An In Vitro Model of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Molecules, 31(2), 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020323