Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Bee Bread Collected in Three Consecutive Beekeeping Seasons in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Phenolic Compound Profile

2.2. Total Phenolic Content (TPC) and Antioxidant Activity

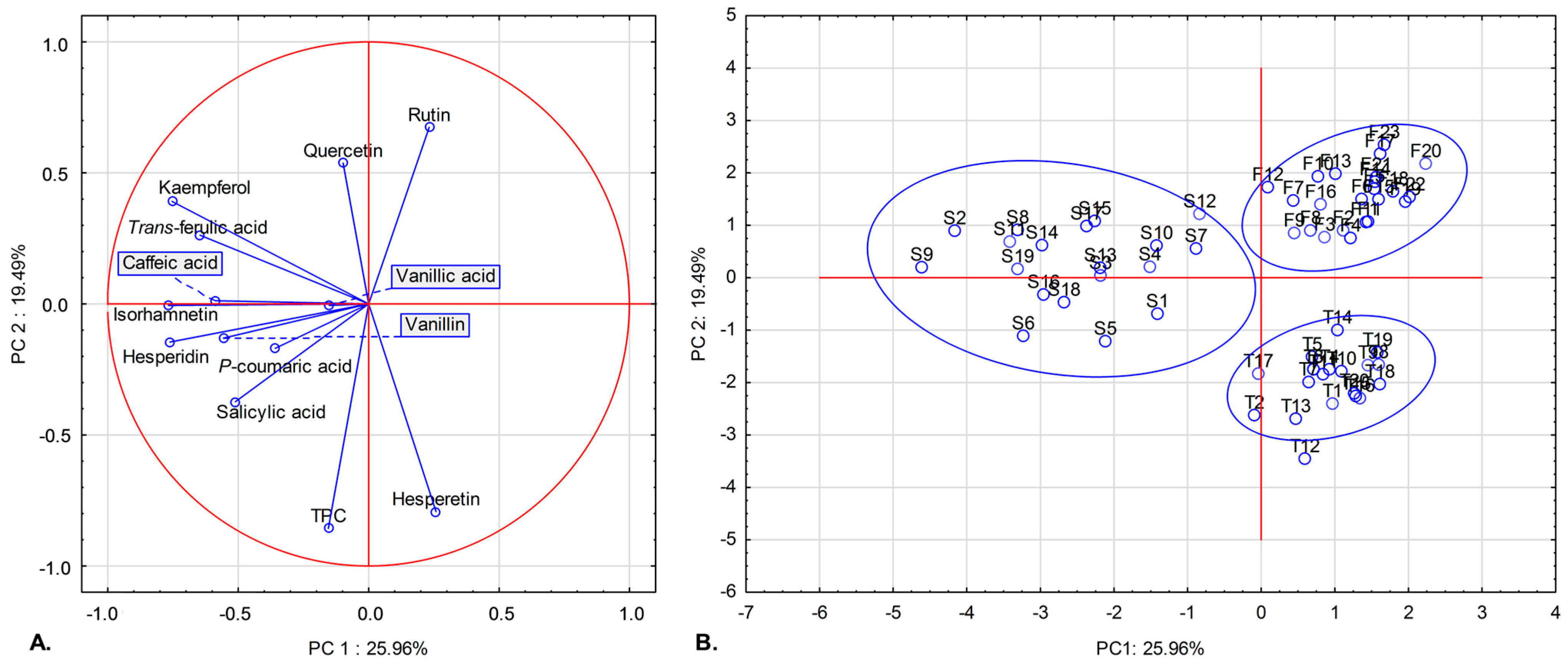

2.3. Principal Component Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample Collection

3.2. Reagents

3.3. Extract Preparation

3.4. HPLC-DAD Analysis

3.5. Determination of Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

3.6. Determination of Antioxidant Activity Against the DPPH Radical

3.7. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rasouli, H.; Farzaei, M.H.; Khodarahmi, R. Polyphenols and Their Benefits: A Review. Inter. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 1700–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Samtiya, M.; Dhewa, T.; Mishra, V.; Aluko, R.E. Health Benefits of Polyphenols: A Concise Review. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manach, C.; Scalbert, A.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, C.; Jiménez, L. Polyphenols: Food Sources and Bioavailability. Am. J. Clin. Nut. 2004, 79, 727–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangney, C.C.; Rasmussen, H.E. Polyphenols, Inflammation, and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2013, 15, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambole, A.N.; Meena, S.N.; Nandre, V.S.; Kodam, K.M. Natural Compounds in Chemopreventive Foods for Prevention and Management of Non-Communicable Diseases. In New Horizons in Natural Compound Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 267–291. ISBN 978-0-443-15232-0. [Google Scholar]

- Strumiłło, J.; Gerszon, J.; Rodacka, A. Charakterystyka Związków Fenolowych Pochodzenia Naturalnego ze Szczególnym Uwzględnieniem Ich Roli w Prewencji Chorób Neurodegeneracyjnych; Gwoździński, K., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2015; pp. 231–245. [Google Scholar]

- Cory, H.; Passarelli, S.; Szeto, J.; Tamez, M.; Mattei, J. The Role of Polyphenols in Human Health and Food Systems: A Mini-Review. Front. Nutr. 2018, 5, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciupei, D.; Colişar, A.; Leopold, L.; Stănilă, A.; Diaconeasa, Z.M. Polyphenols: From Classification to Therapeutic Potential and Bioavailability. Foods 2024, 13, 4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Saadony, M.T.; Yang, T.; Saad, A.M.; Alkafaas, S.S.; Elkafas, S.S.; Eldeeb, G.S.; Mohammed, D.M.; Salem, H.M.; Korma, S.A.; Loutfy, S.A.; et al. Polyphenols: Chemistry, Bioavailability, Bioactivity, Nutritional Aspects and Human Health Benefits: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakour, M.; Laaroussi, H.; Ousaaid, D.; El Ghouizi, A.; Es-Safi, I.; Mechchate, H.; Lyoussi, B. Bee Bread as a Promising Source of Bioactive Molecules and Functional Properties: An Up-To-Date Review. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, D.G.; Cornea-Cipcigan, M.; Margaoan, R.; Vodnar, D.C. Biotechnological Processes Simulating the Natural Fermentation Process of Bee Bread and Therapeutic Properties—An Overview. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 871896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, A.; Altunatmaz, S.S.; Aksu, F.; Tokatlı Demirok, N.; Yazıcı, K.; Yıkmış, S. Bee Bread as a Functional Product: Phenolic Compounds, Amino Acid, Sugar, and Organic Acid Profiles. Foods 2024, 13, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, Z.; Gıdık, B.; Kara, Y.; Kolaylı, S. Antioxidant Activity and Phenolic Content of Bee Breads from Different Regions of Türkiye by Chemometric Analysis (PCA and HCA). Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 2961–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, C.-I.; Spoiala, A.; Geana, E.-I.; Chircov, C.; Ficai, A.; Ditu, L.-M.; Oprea, E. Bee Bread: A Promising Source of Bioactive Compounds with Antioxidant Properties—First Report on Some Antimicrobial Features. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarbati, A.; Canonico, L.; Gattucci, S.; Ciani, M.; Comitini, F. From Pollen to Bee Bread: A Reservoir of Functional Yeasts. Fermentation 2025, 11, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülbaz, G.; Akbaba, G.B.; Öztürkkan, F.E. Assessment of Chemical Composition and in Vitro and in Silico Anticarcinogenic Activity of Bee Bread Samples from Eastern Anatolia (Kars). Eur. Food. Res. Technol. 2025, 251, 899–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urcan, A.C.; Marghitas, L.A.; Dezmirean, D.S.; Bobis, O.; Bonta, V.; Muresan, C.I.; Margaoan, R. Chemical Composition and Biological Activities of Beebread—Review. Bull. Univ. Agric. Sci. Vet. Med. Cluj-Napoca. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 74, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieliszek, M.; Piwowarek, K.; Kot, A.M.; Błażejak, S.; Chlebowska-Śmigiel, A.; Wolska, I. Pollen and Bee Bread as New Health-Oriented Products: A Review. Trends Food Scien. Technol. 2018, 71, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mărgăoan, R.; Stranț, M.; Varadi, A.; Topal, E.; Yücel, B.; Cornea-Cipcigan, M.; Campos, M.G.; Vodnar, D.C. Bee Collected Pollen and Bee Bread: Bioactive Constituents and Health Benefits. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćirić, J.; Haneklaus, N.; Rajić, S.; Baltić, T.; Lazić, I.B.; Đorđević, V. Chemical Composition of Bee Bread (Perga), a Functional Food: A Review. J. Trace Elem. Min. 2022, 2, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baky, M.H.; Abouelela, M.B.; Wang, K.; Farag, M.A. Bee Pollen and Bread as a Super-Food: A Comparative Review of Their Metabolome Composition and Quality Assessment in the Context of Best Recovery Conditions. Molecules 2023, 28, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyvan, N.; Usluer, M.S.; Kaya, M.M.; Kahraman, H.A.; Tutun, H.; Keyvan, E. Total Phenolic Content, Antibacterial and Antiradical Properties of Bee Bread from Turkey. MAEU Vet. Fak. Derg. 2023, 8, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolayli, S.; Birinci, C.; Kanbur, E.D.; Ucurum, O.; Kara, Y.; Takma, C. Comparison of Biochemical and Nutritional Properties of Bee Pollen Samples According to Botanical Differences. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaškonienė, V.; Adaškevičiūtė, V.; Kaškonas, P.; Mickienė, R.; Maruška, A. Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities of Natural and Fermented Bee Pollen. Food Biosci. 2020, 34, 100532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markiewicz-Żukowska, R.; Naliwajko, S.K.; Bartosiuk, E.; Moskwa, J.; Isidorov, V.; Soroczyńska, J.; Borawska, M.H. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Beebread, and Its Influence on the Glioblastoma Cell Line (U87MG). J. Api. Sci. 2013, 57, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dranca, F.; Ursachi, F.; Oroian, M. Bee Bread: Physicochemical Characterization and Phenolic Content Extraction Optimization. Foods 2020, 9, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsayed, N.; El-Din, H.S.; Altemimi, A.B.; Ahmed, H.Y.; Pratap-Singh, A.; Abedelmaksoud, T.G. In Vitro Antimicrobial, Antioxidant and Anticancer Activities of Egyptian Citrus Beebread. Molecules 2021, 26, 2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawicki, T.; Starowicz, M.; Kłębukowska, L.; Hanus, P. The Profile of Polyphenolic Compounds, Contents of Total Phenolics and Flavonoids, and Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of Bee Products. Molecules 2022, 27, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidorov, V.A.; Isidorova, A.G.; Sczczepaniak, L.; Czyżewska, U. Gas Chromatographic–Mass Spectrometric Investigation of the Chemical Composition of Beebread. Food Chem. 2009, 115, 1056–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobral, F.; Calhelha, R.; Barros, L.; Dueñas, M.; Tomás, A.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Vilas-Boas, M.; Ferreira, I. Flavonoid Composition and Antitumor Activity of Bee Bread Collected in Northeast Portugal. Molecules 2017, 22, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urcan, A.C.; Criste, A.D.; Dezmirean, D.S.; Mărgăoan, R.; Caeiro, A.; Graça Campos, M. Similarity of Data from Bee Bread with the Same Taxa Collected in India and Romania. Molecules 2018, 23, 2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovi, T.D.S.; Caeiro, A.; Dos Santos, S.A.A.; Zaluski, R.; Shinohara, A.J.; Lima, G.P.P.; Campos, M.D.G.R.; Junior, L.A.J.; Orsi, R.D.O. Seasonal Variation of Flavonoid Content in Bee Bread: Potential Impact on Hypopharyngeal Gland Development in Apis Mellifera Honey Bees. J. Api. Res. 2019, 59, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, N.E.; Gercek, Y.C.; Çelik, S.; Mayda, N.; Kostić, A.Ž.; Dramićanin, A.M.; Özkök, A. Phenolic and Free Amino Acid Profiles of Bee Bread and Bee Pollen with the Same Botanical Origin—Similarities and Differences. Arab. J. Chem. 2021, 14, 103004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marieke, M.; van Blitterswijk, H.; Leven, L.; Kerkvliet, J.; Waerdt, J. Bee Products (Properties, Processing and Marketing). Agrodok 2005, 42, 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Semkiw, P.; Skubida, P. Bee Bread Production—A New Source of Income for Beekeeping Farms? Agriculture 2021, 11, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuluaga, C.M.; Serratob, J.C.; Quicazana, M.C. Chemical, Nutritional and Bioactive Characterization of Colombian Bee-Bread. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2015, 43, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miłek, M.; Mołoń, M.; Kula-Maximenko, M.; Sidor, E.; Zaguła, G.; Dżugan, M. Chemical Composition and Bioactivity of Laboratory-Fermented Bee Pollen in Comparison with Natural Bee Bread. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pełka, K.; Otłowska, O.; Worobo, R.W.; Szweda, P. Bee Bread Exhibits Higher Antimicrobial Potential Compared to Bee Pollen. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erol, E. Quantitative Analysis of Bioaccessible Phenolic Compounds in Aegean Bee Bread Using LC-HRMS Coupled with a Human Digestive System Model. Chem. Biodivers. 2024, 21, e202301497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutlu, N.; Gerçek, Y.C.; Çelik, S.; Bayram, S.; Ecem Bayram, N. An Optimization Study for Amino Acid Extraction from Bee Bread Using Choline Chloride-Acetic Acid Deep Eutectic Solvent and Determination of Individual Phenolic Profile. Food Meas. 2024, 18, 1026–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urcan, A.C.; Criste, A.D.; Dezmirean, D.S.; Bobiș, O.; Bonta, V.; Burtescu, R.F.; Olah, N.K.; Cornea-Cipcigan, M.; Mărgăoan, R. Enhancing antioxidant and antimicrobial activities in bee-collected pollen through solid-state fermentation: A comparative analysis of bioactive compounds. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, T.; Ruszkowska, M.; Shin, J.; Starowicz, M. Free and Conjugated Phenolic Compounds Profile and Antioxidant Activities of Honeybee Products of Polish Origin. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2022, 248, 2263–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonmez, E.; Kekecoglu, M.; Sahin, H.; Bozdeveci, A.; Karaoglu, S.A. Comparing the Biological Properties and Chemical Profiling of Chestnut Bee Pollen and Bee Bread Collected from Anatolia. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2023, 54, 2307–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylanc, V.; Tomás, A.; Russo-Almeida, P.; Falcão, S.I.; Vilas-Boas, M. Assessment of Bioactive Compounds under Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion of Bee Pollen and Bee Bread: Bioaccessibility and Antioxidant Activity. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izol, E.; Yılmaz, M.A.; Gülçin, İ. Chemical Characterization by Chromatography Techniques and Comprehensive Biological Activities of Artvin Bee Products. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e202501545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, M.G.R.; Bogdanov, S.; De Almeida-Muradian, L.B.; Szczęsna, T.; Mancebo, Y.; Frigerio, C.; Ferreira, F. Pollen Composition and Standardisation of Analytical Methods. J. Api. Res. 2008, 47, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćeksteryté, V.; Kurtinaitienė, B.; Venskutonis, P.R.; Pukalskas, A.; Kazernavičiuté, R.; Balžekas, J. Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity and Flavonoid Composition in Differently Preserved Bee Products. Czech. J. Food Sci. 2016, 34, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayda, N.; Özkök, A.; Ecem Bayram, N.; Gerçek, Y.C.; Sorkun, K. Bee Bread and Bee Pollen of Different Plant Sources: Determination of Phenolic Content, Antioxidant Activity, Fatty Acid and Element Profiles. Food Meas. 2020, 14, 1795–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervyïşoğlu, G.; Çobanoğlu, D.N.; Yelkovan, S.; Karahan, D.; Çakir, Y.; KoçyïğyïT, S. Comprehensive Study on BeeBread: Palynological Analysis, Chemical Composition, Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Activities. Int. J. Sec. Metab. 2022, 9, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhir, R.A.M.; Bakar, M.F.A.; Sanusi, S.B. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity of Stingless Bee Bread and Propolis Extracts. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Applied Science and Technology 2017 (ICAST’17), Kedah, Malaysia, 3–5 April 2017; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 1891, p. 020090. [Google Scholar]

- Suleiman, J.B.; Mohamed, M.; Abu Bakar, A.B.; Nna, V.U.; Zakaria, Z.; Othman, Z.A.; Aroyehun, A.B. Chemical Profile, Antioxidant Properties and Antimicrobial Activities of Malaysian Heterotrigona Itama Bee Bread. Molecules 2021, 26, 4943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, I.G.; Apetrei, C. Analytical Methods Used in Determining Antioxidant Activity: A Review. IJMS 2021, 22, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanciu, O.; Mărghitaş, L.A.; Dezmirean, D. Examination of Antioxidant Capacity of Beebread Extracts by Different Complementary Assays. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2007, 63/64, 204–207. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanišová, E.; Kačániová, M.; Frančáková, H.; Petrová, J.; Hutková, J.; Brovarskyi, V.; Velychko, S.; Adamchuk, L.; Schubertová, Z.; Musilová, J. Bee Bread—Perspective Source of Bioactive Compounds for Future. Slovak J. Food Sci. Potravin. 2015, 9, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaycıoğlu, Z.; Kanbur, E.D.; Kolaylı, S.; Erim, F.B. Antioxidant Activities, Aliphatic Organic Acid and Sugar Contents of Anatolian Bee Bread: Characterization by Principal Component Analysis. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 1351–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.S.; Bezerra, M.A.; Cerqueira, U.M.F.M.; Rodrigues, C.J.O.; Santos, B.C.; Novaes, C.G.; Almeida, E.R.V. An Introductory Review on the Application of Principal Component Analysis in the Data Exploration of the Chemical Analysis of Food Samples. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 33, 1323–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çobanoğlu, D.N.; Şeker, M.E.; Temizer, I.K.; Erdoğan, A. Investigation of botanical origin, phenolic compounds, carotenoids, and antioxidant properties of monofloral and multifloral bee bread. Chem. Biodivers. 2023, 20, e202201124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waś, E.; Szczęsna, T.; Rybak-Chmielewska, H.; Teper, D.; Jaśkiewicz, K. Application of HPLC-DAD Technique for Determination of Phenolic Compounds in Bee Pollen Loads. J. Api. Sci. 2017, 61, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meda, A.; Lamien, C.E.; Romito, M.; Millogo, J.; Nacoulma, O.G. Determination of the Total Phenolic, Flavonoid and Proline Contents in Burkina Fasan Honey, as Well as Their Radical Scavenging Activity. Food Chem. 2005, 91, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekindal, M.A.; Erdoğan, B.D.; Yavuz, Y. Evaluating left-censored data through substitution, parametric, semi-parametric, and nonparametric methods: A simulation study. Interdiscip. Sci. Comput. Life Sci. 2017, 9, 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhu, P.; Xu, B.; Zhao, R.; Qiao, S.; Chen, X.; Tang, R.; Wu, D.; Song, L.; Wang, S.; et al. Determination of Nine Environmental Phenols in Urine by Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2012, 36, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaśkiewicz, K.; Szczęsna, T.; Jachuła, J. How Phenolic Compounds Profile and Antioxidant Activity Depend on Botanical Origin of Honey—A Case of Polish Varietal Honeys. Molecules 2025, 30, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phenolic Compound | 2015 (n = 23) | 2016 (n = 19) | 2017 (n = 20) | 2015–2017 (n = 62) | Test Statistic H | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Coumaric Acid | 195.02 ± 93.42 A (47.90%) | 274.63 ± 235.64 A (85.80%) | 210.58 ± 76.61 A (36.38%) | 224.44 ± 150.11 (66.88%) | 0.336 | 0.846 |

| trans-Ferulic Acid | 87.53 ± 26.70 B (30.50%) | 187.15 ± 100.43 C (53.66%) | 40.73 ± 8.52 A (20.91%) | 102.96 ± 82.60 (80.22%) | 51.363 | <0.001 |

| Caffeic Acid | 69.80 ± 25.07 A (35.92%) | 111.85 ± 33.69 B (30.12%) | 72.51 ± 39.89 A (55.01%) | 83.56 ± 37.66 (45.07%) | 20.020 | <0.001 |

| Vanillic Acid | 58.22 ± 32.27 A (55.43%) | 67.84 ± 27.83 A (41.02%) | 51.85 ± 68.78 A (132.67%) | 59.11 ± 46.03 (77.88%) | 4.408 | 0.110 |

| Salicylic Acid | <LOD * | 115.69 ± 67.21 B (58.09%) | 72.72 ± 86.93 A (119.54%) | 60.44 ± 77.20 (127.73%) | 32.909 | <0.001 |

| Vanillin | 22.28 ± 17.76 A (79.69%) | 143.81 ± 171.09 AB (118.97%) | 46.19 ± 14.09 B (30.51%) | 67.23 ± 107.45 (159.82%) | 8.630 | 0.013 |

| Rutin | 1390.68 ± 773.55 C (55.62%) | 563.35 ± 281.61 B (49.99%) | 270.61 ± 181.41 A (67.04%) | 775.83 ± 699.82 (90.20%) | 33.607 | <0.001 |

| Hesperidin | 323.97 ± 175.93 A (54.31%) | 636.85 ± 96.52 B (15.16%) | 410.43 ± 86.59 A (21.10%) | 447.74 ± 183.35 (40.95%) | 33.527 | <0.001 |

| Hesperetin | 128.06 ± 86.32 A (67.41%) | 141.72 ± 164.93 A (116.38%) | 503.87 ± 121.22 B (24.06%) | 253.48 ± 213.70 (84.31%) | 33.934 | <0.001 |

| Kaempferol | 96.95 ± 39.82 B (41.07%) | 179.89 ± 76.64 C (42.60%) | 56.09 ± 17.82 A (31.77%) | 109.19 ± 70.30 (64.38%) | 33.714 | <0.001 |

| Quercetin | 89.80 ± 26.72 B (29.76%) | 94.85 ± 36.89 B (38.89%) | 66.21 ± 17.64 A (26.65%) | 83.74 ± 30.15 (36.01%) | 9.826 | 0.007 |

| Isorhamnetin | 22.33 ± 8.48 A (37.99%) | 139.83 ± 88.20 C (63.08%) | 44.62 ± 12.36 B (27.71%) | 65.53 ± 70.26 (107.22%) | 42.987 | <0.001 |

| Sum of phenolic acids | 414.68 ± 80.04 A (19.30%) | 757.16 ± 269.34 B (35.57%) | 448.40 ± 131.37 A (29.30%) | 530.51 ± 228.83 (43.13%) | 29.793 | <0.001 |

| Sum of flavonoids | 2051.79 ± 861.80 B (42.00%) | 1756.49 ± 369.07 B (21.01%) | 1351.82 ± 275.39 A (20.37%) | 1735.50 ± 646.37 (37.24%) | 10.191 | 0.006 |

| Sum of phenolic compounds | 2488.75 ± 885.68 B (35.59%) | 2657.47 ± 539.13 B (20.29%) | 1846.40 ± 315.41 A (17.08%) | 2333.24 ± 720.58 (30.88%) | 15.803 | <0.001 |

| Characteristics | 2015 (n = 23) | 2016 (n = 19) | 2017 (n = 20) | 2015–2017 (n = 62) | Test Statistic H | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total phenolic content (TPC) (mg GAE/100 g) | 873.33 ± 113.52 A (13.00%) | 1201.35 ± 85.65 B (7.13%) | 1469.15 ± 110.87 C (7.55%) | 1166.05 ± 271.03 (23.24%) | 51.708 | <0.001 |

| DPPH radical scavenging activity (%) | 94.40 ± 1.50 A (1.59%) | 95.04 ± 0.88 A (0.93%) | 94.69 ± 1.21 A (1.28%) | 94.69 ± 1.25 (1.32%) | 1.263 | 0.532 |

| Variable | Correlation Coefficient with DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2015–2017 | |||||

| rho | p | rho | p | rho | p | rho | p | |

| p-Coumaric Acid | 0.724 * | <0.001 | 0.335 | 0.161 | 0.523 | 0.018 | 0.579 | <0.001 |

| trans-Ferulic Acid | −0.530 | 0.009 | −0.280 | 0.245 | 0.305 | 0.190 | −0.017 | 0.896 |

| Caffeic Acid | −0.174 | 0.427 | −0.350 | 0.142 | 0.122 | 0.609 | −0.050 | 0.698 |

| Vanillic Acid | 0.216 | 0.323 | −0.375 | 0.114 | −0.431 | 0.058 | −0.121 | 0.349 |

| Salicylic Acid | - | - | 0.320 | 0.182 | −0.302 | 0.196 | 0.009 | 0.947 |

| Vanillin | −0.006 | 0.978 | −0.463 | 0.046 | −0.114 | 0.631 | −0.158 | 0.220 |

| Rutin | −0.081 | 0.715 | −0.499 | 0.030 | 0.193 | 0.415 | −0.135 | 0.295 |

| Hesperidin | 0.529 | 0.009 | 0.182 | 0.455 | 0.375 | 0.103 | 0.364 | 0.004 |

| Hesperetin | −0.344 | 0.108 | −0.253 | 0.296 | 0.089 | 0.710 | −0.271 | 0.033 |

| Kaempferol | 0.206 | 0.345 | −0.121 | 0.621 | 0.006 | 0.980 | 0.099 | 0.446 |

| Quercetin | −0.575 | 0.004 | −0.118 | 0.629 | −0.144 | 0.546 | −0.214 | 0.095 |

| Isorhamnetin | 0.103 | 0.639 | 0.038 | 0.877 | 0.237 | 0.314 | 0.133 | 0.304 |

| Sum of phenolic acids | 0.695 | <0.001 | −0.080 | 0.743 | −0.054 | 0.821 | 0.290 | 0.022 |

| Sum of flavonoids | 0.068 | 0.759 | −0.604 | 0.006 | 0.237 | 0.315 | −0.001 | 0.991 |

| Sum of phenolic compounds | 0.105 | 0.633 | −0.561 | 0.012 | 0.306 | 0.189 | 0.040 | 0.755 |

| Total phenolic content (TPC) | 0.052 | 0.812 | −0.249 | 0.303 | 0.117 | 0.624 | 0.014 | 0.914 |

| Variable | Principal Component | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| p-Coumaric Acid | −0.36 | −0.17 | 0.01 | −0.77 | −0.20 |

| trans-Ferulic Acid | −0.65 | 0.26 | −0.54 | 0.18 | 0.00 |

| Caffeic Acid | −0.59 | 0.01 | −0.56 | 0.06 | 0.26 |

| Vanillic Acid | −0.15 | −0.01 | −0.06 | 0.44 | −0.86 |

| Salicylic Acid | −0.51 | −0.37 | 0.29 | 0.26 | −0.08 |

| Vanillin | −0.56 | −0.13 | −0.64 | −0.19 | −0.14 |

| Rutin | 0.23 | 0.67 | −0.27 | −0.10 | 0.04 |

| Hesperidin | −0.76 | −0.15 | 0.32 | −0.26 | 0.01 |

| Hesperetin | 0.26 | −0.79 | −0.32 | 0.20 | 0.05 |

| Kaempferol | −0.75 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Quercetin | −0.10 | 0.54 | 0.03 | 0.49 | 0.23 |

| Isorhamnetin | −0.77 | −0.01 | 0.34 | 0.22 | 0.15 |

| Total phenolic content (TPC) | −0.15 | −0.86 | −0.01 | 0.22 | 0.23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Szczęsna, T.; Jaśkiewicz, K.; Skubij, N.; Jachuła, J. Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Bee Bread Collected in Three Consecutive Beekeeping Seasons in Poland. Molecules 2026, 31, 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020304

Szczęsna T, Jaśkiewicz K, Skubij N, Jachuła J. Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Bee Bread Collected in Three Consecutive Beekeeping Seasons in Poland. Molecules. 2026; 31(2):304. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020304

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzczęsna, Teresa, Katarzyna Jaśkiewicz, Natalia Skubij, and Jacek Jachuła. 2026. "Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Bee Bread Collected in Three Consecutive Beekeeping Seasons in Poland" Molecules 31, no. 2: 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020304

APA StyleSzczęsna, T., Jaśkiewicz, K., Skubij, N., & Jachuła, J. (2026). Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Bee Bread Collected in Three Consecutive Beekeeping Seasons in Poland. Molecules, 31(2), 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020304