Poly(levodopa)-Modified β-(1 → 3)-D-Glucan Hydrogel Enriched with Triangle-Shaped Nanoparticles as a Biosafe Matrix with Enhanced Antibacterial Potential

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of the Silver Nanoparticles

2.2. Heat Generation and Active Substance Release Process

2.3. Mechanical and Surface Properties

2.4. Characterization of the Porosity

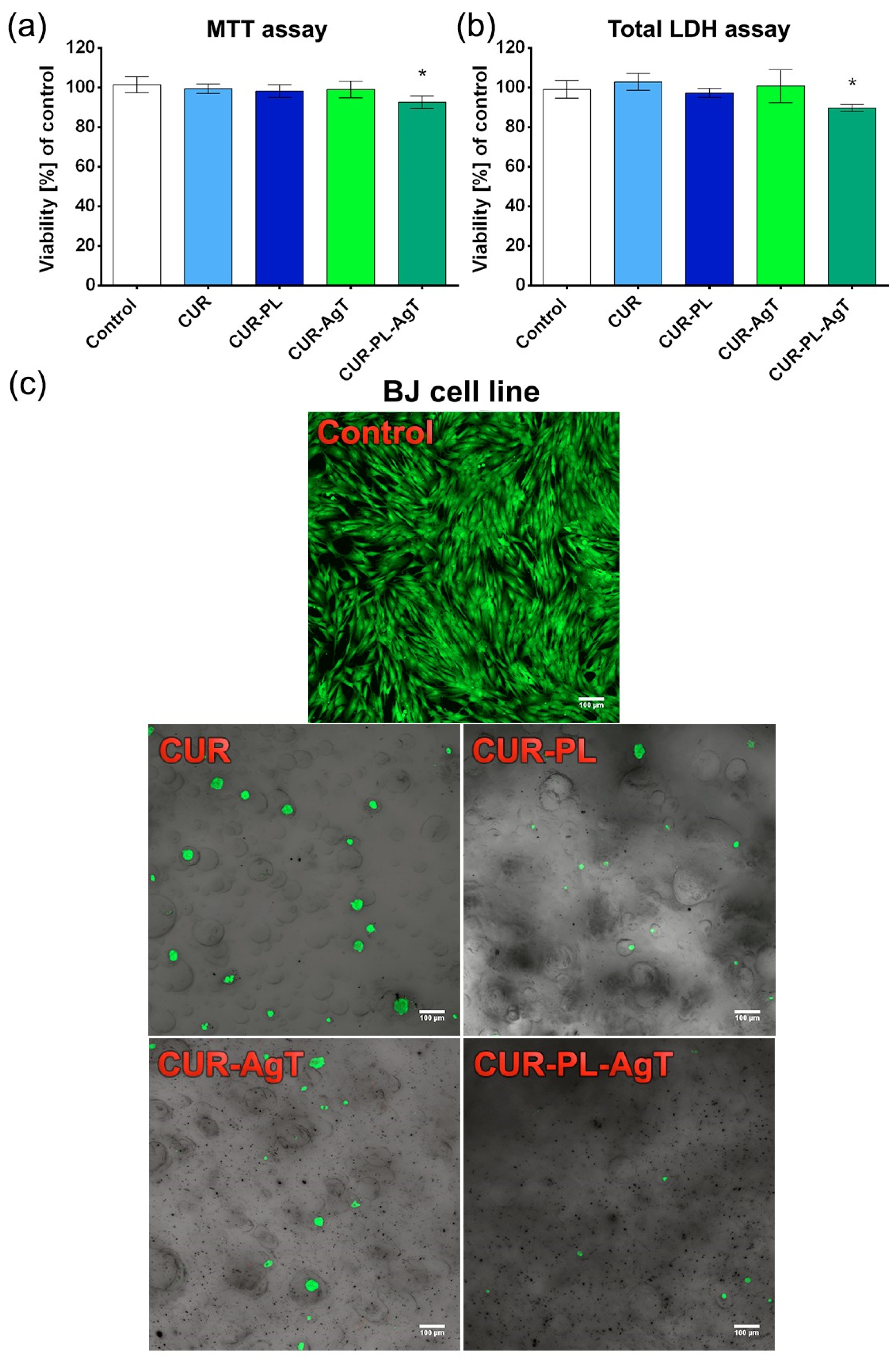

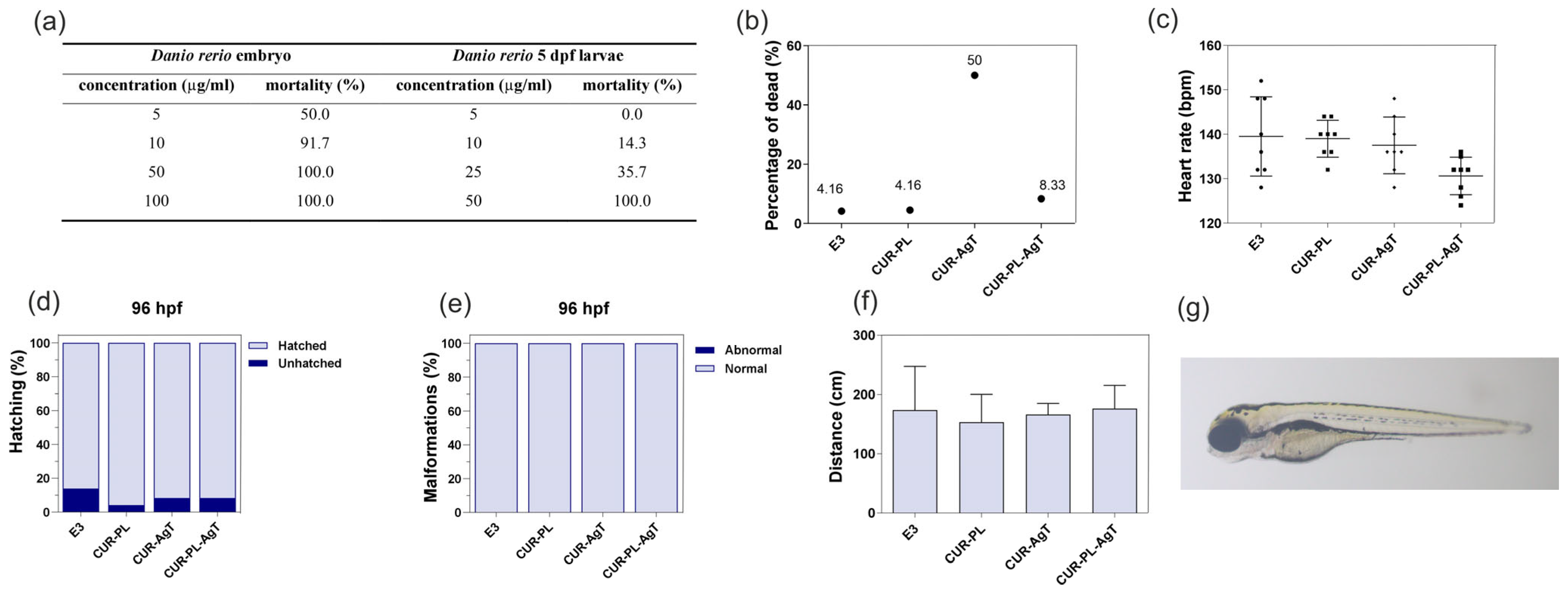

2.5. Cytotoxicity and Toxicity in Fibroblasts and Zebrafish Model

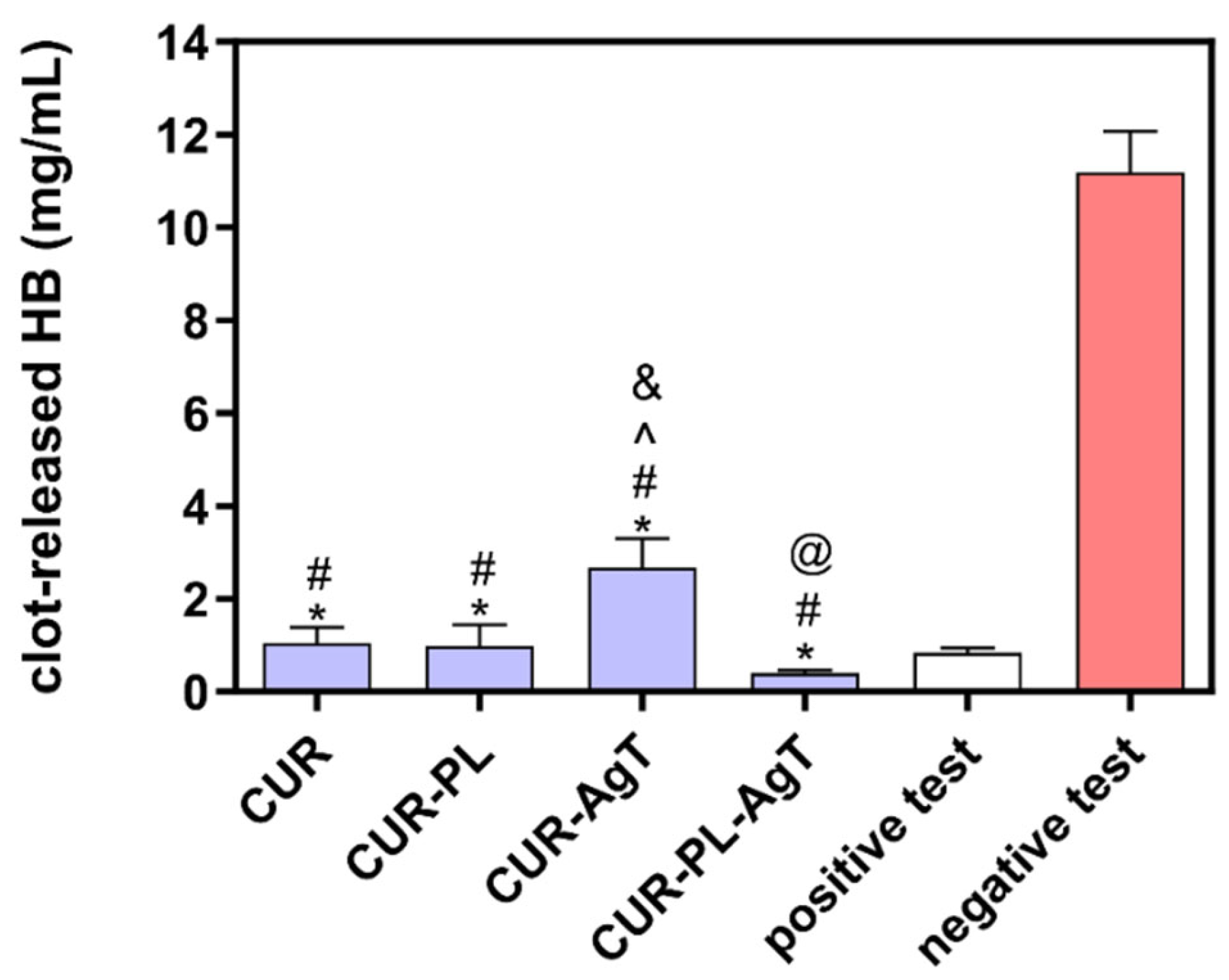

2.6. Hemocompatibility

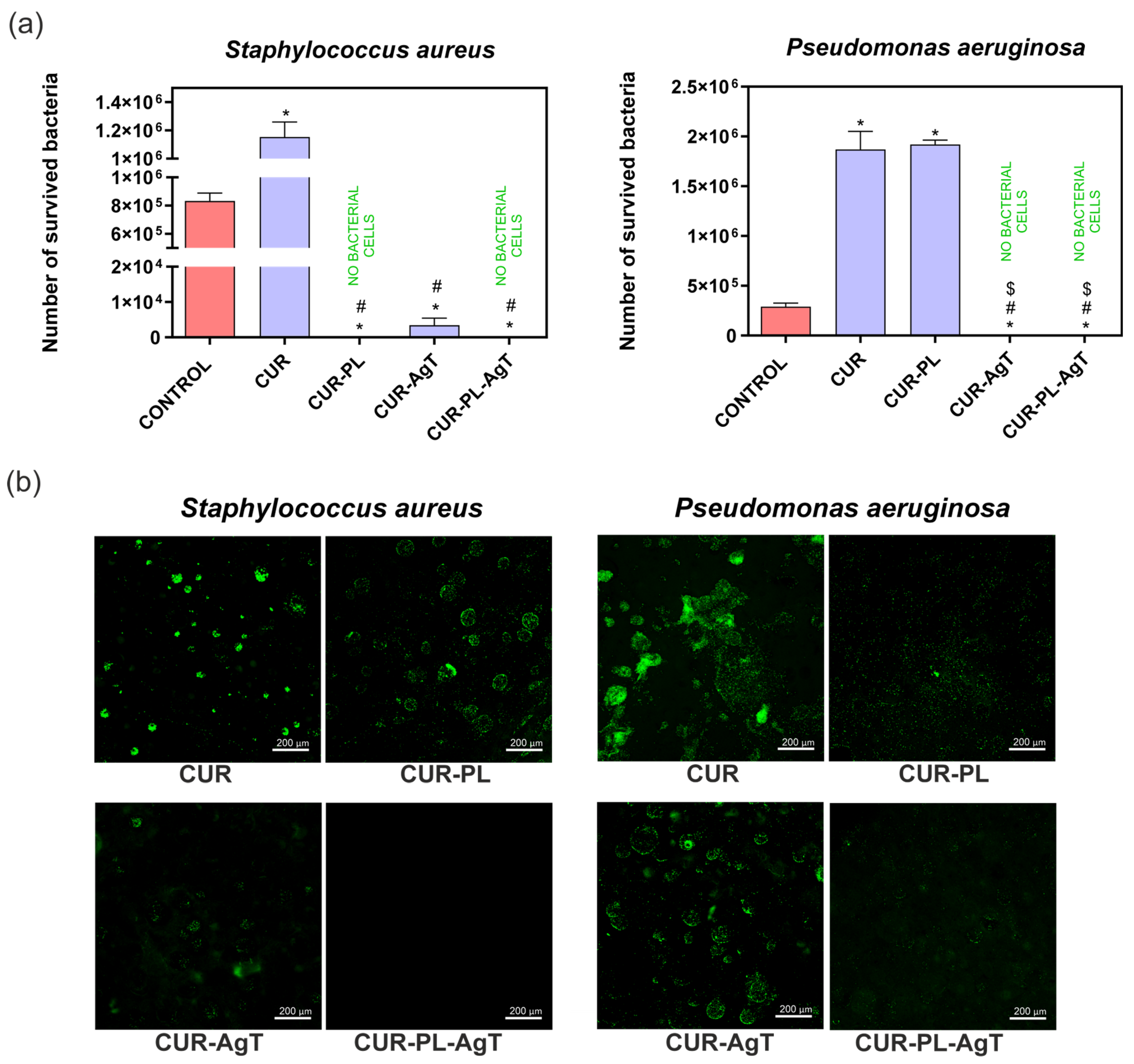

2.7. Antibacterial Properties

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Synthesis of the Nanoprism Ag Nanoparticles

3.2.2. Characterization of Ag Nanoparticles

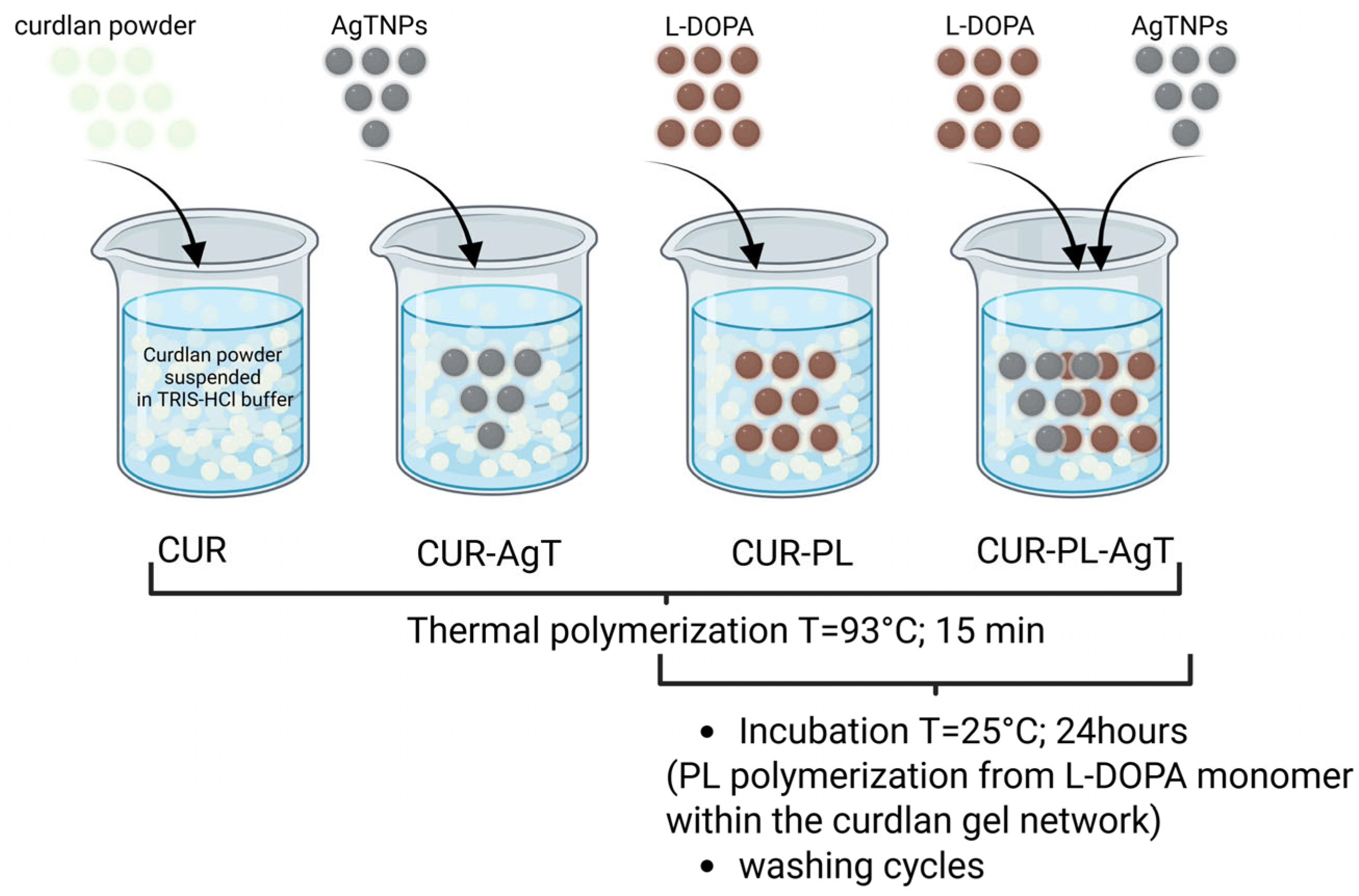

3.2.3. Synthesis of Hydrogel Samples

3.2.4. NIR Energy Conversion on Hydrogels

3.2.5. Nanoparticles and Ions Release

3.2.6. Mechanical Tests

3.2.7. Surface Properties

Wettability Characterization

Surface Roughness Parameters

Characterization of the Porosity

3.2.8. Cytotoxicity Evaluation

3.2.9. In Vivo Experiments—Danio rerio Model

3.2.10. Clot Formation Test

3.2.11. Antibacterial Activity Evaluation

Bacterial Strains and Maintenance

Antibacterial Activity Test (Based on the Standard: AATCC Test Method 100-2004)

Bacterial Adhesion Test

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cai, Z.; Zhang, H. Recent Progress on Curdlan Provided by Functionalization Strategies. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 68, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Gao, F.P.; Tang, H.B.; Bai, Y.G.; Li, R.F.; Li, X.M.; Liu, L.R.; Wang, Y.S.; Zhang, Q.Q. Self-Assembled Nanoparticles of Cholesterol-Conjugated Carboxymethyl Curdlan as a Novel Carrier of Epirubicin. Nanotechnology 2010, 21, 265601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdal, M.; Appelbom, H.I.; Eikrem, J.H.; Lund, Å.; Busund, L.T.; Hanes, R.; Seljelid, R.; Jenssen, T. Aminated β-1,3-D-Glucan Has a Dose-Dependent Effect on Wound Healing in Diabetic Db/Db Mice. Wound Repair Regen. 2011, 19, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osawa, Z.; Morota, T.; Hatanaka, K.; Akaike, T.; Matsuzaki, K.; Nakashima, H.; Yamamoto, N.; Suzuki, E.; Miyano, H.; Mimura, T.; et al. Synthesis of Sulfated Derivatives of Curdlan and Their Anti-HIV Activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 1993, 21, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, I.; Takayama, K.; Gonda, T.; Matsuzaki, K.; Hatanaka, K.-I.; Yoshida, T.; Uryu, T.; Yoshida, O.; Nakashima, H.; Yamamoto, N.; et al. Synthesis, Structure and Antiviral Activity of Sulfates of Curdlan and Its Branched Derivatives. Br. Polym. J. 1990, 23, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Abiko, N.; Sugino, Y.; Nitta, K. Dependence on Chain Length of Antitumor Activity of (1 → 3)-β-D-Glucan from Alcaligenes faecalis var. myxogenes, IFO 13140, and Its Acid-Degraded Products. Cancer Res. 1978, 38, 379–383. [Google Scholar]

- Przekora, A.; Benko, A.; Blazewicz, M.; Ginalska, G. Hybrid Chitosan/β-1,3-Glucan Matrix of Bone Scaffold Enhances Osteoblast Adhesion, Spreading and Proliferation via Promotion of Serum Protein Adsorption. Biomed. Mater. 2016, 11, 045001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcarz, A.; Ginalska, G.; Pycka, T.; Zima, A.; Ślósarczyk, A.; Polkowska, I.; Paszkiewicz, Z.; Piekarczyk, W. Application of β-1,3-Glucan in Production of Ceramics-Based Elastic Composite for Bone Repair. Cent. Eur. J. Biol. 2013, 8, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkowski, L.; Pawłowska, M.; Radzki, R.P.; Bieńko, M.; Polkowska, I.; Belcarz, A.; Karpiński, M.; Słowik, T.; Matuszewski, L.; ͆lósarczyk, A.; et al. Effect of a Carbonated HAP/β-Glucan Composite Bone Substitute on Healing of Drilled Bone Voids in the Proximal Tibial Metaphysis of Rabbits. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 53, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroka-Bartnicka, A.; Kimber, J.A.; Borkowski, L.; Pawlowska, M.; Polkowska, I.; Kalisz, G.; Belcarz, A.; Jozwiak, K.; Ginalska, G.; Kazarian, S.G. The Biocompatibility of Carbon Hydroxyapatite/β-Glucan Composite for Bone Tissue Engineering Studied with Raman and FTIR Spectroscopic Imaging. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 7775–7785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangli, H.; Vatanpour, S.; Hortamani, S.; Jalili, R.; Ghahary, A. Incorporation of Silver Nanoparticles in Hydrogel Matrices for Controlling Wound Infection. J. Burn. Care Res. 2021, 42, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherasim, O.; Puiu, R.A.; Bîrca, A.C.; Burduşel, A.C.; Grumezescu, A.M. An Updated Review on Silver Nanoparticles in Biomedicine. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osonga, F.J.; Akgul, A.; Yazgan, I.; Akgul, A.; Eshun, G.B.; Sakhaee, L.; Sadik, O.A. Size and Shape-Dependent Antimicrobial Activities of Silver and Gold Nanoparticles: A Model Study as Potential Fungicides. Molecules 2020, 25, 2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, J.Y.; Kim, S.J.; Rhee, Y.H.; Kwon, O.H.; Park, W.H. Shape-Dependent Antimicrobial Activities of Silver Nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 2773–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz Ahmed, K.B.; Nagy, A.M.; Brown, R.P.; Zhang, Q.; Malghan, S.G.; Goering, P.L. Silver Nanoparticles: Significance of Physicochemical Properties and Assay Interference on the Interpretation of in Vitro Cytotoxicity Studies. Toxicol. Vitr. 2017, 38, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, N.; Durán, M.; de Jesus, M.B.; Seabra, A.B.; Fávaro, W.J.; Nakazato, G. Silver Nanoparticles: A New View on Mechanistic Aspects on Antimicrobial Activity. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2016, 12, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrag, C.; Li, S.; Jeon, K.; Andoy, N.M.; Sullan, R.M.A.; Mikhaylichenko, S.; Kerman, K. Polyacrylamide Hydrogels Doped with Different Shapes of Silver Nanoparticles: Antibacterial and Mechanical Properties. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2021, 197, 111397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, K.; Jaggi, N. Localized Surface Plasmonic Properties of Au and Ag Nanoparticles for Sensors: A Review. Plasmonics 2021, 16, 981–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Phillips, S.; Northrup, S.; Levi, N. The Impact of Silver Nanoparticle-Induced Photothermal Therapy and Its Augmentation of Hyperthermia on Breast Cancer Cells Harboring Intracellular Bacteria. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaque, D.; Martínez Maestro, L.; Del Rosal, B.; Haro-Gonzalez, P.; Benayas, A.; Plaza, J.L.; Martín Rodríguez, E.; García Solé, J. Nanoparticles for Photothermal Therapies. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 9494–9530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djafari, J.; Fernández-Lodeiro, C.; Fernández-Lodeiro, A.; Silva, V.; Poeta, P.; Igrejas, G.; Lodeiro, C.; Capelo, J.L.; Fernández-Lodeiro, J. Exploring the Control in Antibacterial Activity of Silver Triangular Nanoplates by Surface Coating Modulation. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Dadwal, R.; Nandanwar, H.; Soni, S. Limits of Antibacterial Activity of Triangular Silver Nanoplates and Photothermal Enhancement Thereof for Bacillus Subtilis. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2023, 247, 112787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, Q.K.; Phung, D.D.; Nguyen, Q.N.V.; Thi, H.H.; Thi, N.H.N.; Thi, P.P.N.; Bach, L.G.; Van Tan, L. Controlled Synthesis of Triangular Silver Nanoplates by Gelatin-Chitosan Mixture and the Influence of Their Shape on Antibacterial Activity. Processes 2019, 7, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalicha, A.; Roguska, A.; Przekora, A.; Budzyńska, B.; Belcarz, A. Poly(Levodopa)-Modified β-Glucan as a Candidate for Wound Dressings. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 272, 118485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, N.; Goebl, J.; Lu, Z.; Yin, Y. A Systematic Study of the Synthesis of Silver Nanoplates: Is Citrate a “Magic” Reagent? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 18931–18939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; He, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X. Noble Metal Nanomaterials for NIR-Triggered Photothermal Therapy in Cancer. Adv. Heal. Mater. 2021, 10, 2001806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Yan, S.; Di, C.; Lei, M.; Chen, P.; Du, W.; Jin, Y.; Liu, B.F. “All-in-One” Silver Nanoprism Platform for Targeted Tumor Theranostics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 11329–11340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Chen, X.; Yang, P.; Liang, G.; Yang, Y.; Gu, Z.; Li, Y. Regulating the Absorption Spectrum of Polydopamine. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabb4696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Huang, Y.; You, S.; Xiang, Y.; Cai, E.; Mao, R.; Pan, W.; Tong, X.; Dong, W.; Ye, F.; et al. Engineering Robust Ag-Decorated Polydopamine Nano-Photothermal Platforms to Combat Bacterial Infection and Prompt Wound Healing. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2106015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Yang, P.; Guo, W.; Zhang, Q.P.; Liu, X.; Li, Y. Metal Ion-Promoted Fabrication of Melanin-like Poly(L-DOPA) Nanoparticles for Photothermal Actuation. Sci. China Chem. 2020, 63, 1295–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Baskaran, R.; Ozlu, B.; Davaa, E.; Kim, J.J.; Shim, B.S.; Yang, S.G. T1-Positive Mn2+-Doped Multi-Stimuli Responsive Poly(L-Dopa) Nanoparticles for Photothermal and Photodynamic Combination Cancer Therapy. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalicha, A.; Tomaszewska, A.; Vivcharenko, V.; Budzyńska, B.; Kulpa-Greszta, M.; Fila, D.; Pązik, R.; Belcarz, A. Poly(Levodopa)-Functionalized Polysaccharide Hydrogel Enriched in Fe3O4 Particles for Multiple-Purpose Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Qian, J.; Zhou, L.; Su, Y.; Zhang, R.; Dong, C.M. Biopolymer-Drug Conjugate Nanotheranostics for Multimodal Imaging-Guided Synergistic Cancer Photothermal-Chemotherapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 31576–31588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulpa-Greszta, M.; Tomaszewska, A.; Michalicha, A.; Sikora, D.; Dziedzic, A.; Wojnarowska-Nowak, R.; Belcarz, A.; Pązik, R. Alternating Magnetic Field and NIR Energy Conversion on Magneto-Plasmonic Fe3O4@APTES-Ag Heterostructures with SERS Detection Capability and Antimicrobial Activity. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 27396–27410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, V.; Schumacher-Schuh, A.F.; Rieck, M.; Callegari-Jacques, S.M.; Rieder, C.R.M.; Hutz, M.H. Influence of Genetic, Biological and Pharmacological Factors on Levodopa Dose in Parkinson’s Disease. Pharmacogenomics 2016, 17, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vliet, E.F.; Knol, M.J.; Schiffelers, R.M.; Caiazzo, M.; Fens, M.H.A.M. Levodopa-Loaded Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. J. Control. Release 2023, 360, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, F.; Sawalha, M.; Khawaja, Y.; Najjar, A.; Karaman, R. Dopamine and Levodopa Prodrugs for the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Molecules 2018, 23, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovallath, S.; Sulthana, B. Levodopa: History and Therapeutic Applications. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2017, 20, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Periyasami, G.; Aldalbahi, A.; Fogliano, V. The Antimicrobial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Biocomposite Films Depends on the Silver Ions Release Behaviour. Food Chem. 2021, 359, 129859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, D.; Luan, Y. Microwave Synthesis of Graphene Oxide Decorated with Silver Nanoparticles for Slow-Release Antibacterial Hydrogel. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 31, 103663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Park, J.C.; Jeon, G.E.; Kim, C.S.; Seo, J.H. Effect of the Size and Shape of Silver Nanoparticles on Bacterial Growth and Metabolism by Monitoring Optical Density and Fluorescence Intensity. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2017, 22, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Tang, Y. On Mechanical Properties of Nanocomposite Hydrogels: Searching for Superior Properties. Nano Mater. Sci. 2022, 4, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, K.; He, Y.; Chang, R.; Guan, F.; Yao, M. A Multifunctional Hydrogel Dressing with High Tensile and Adhesive Strength for Infected Skin Wound Healing in Joint Regions. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 11135–11149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, G.; Xu, B.; Feng, X.; Bai, Q.; Yang, G.; Li, H. Thermosensitive Antibacterial Ag Nanocomposite Hydrogels Made by a One-Step Green Synthesis Strategy. New J. Chem. 2016, 40, 6650–6657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Liao, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, F.; Fan, Z. Novel Chitosan Hydrogels Reinforced by Silver Nanoparticles with Ultrahigh Mechanical and High Antibacterial Properties for Accelerating Wound Healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 119, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodabakhshi, D.; Eskandarinia, A.; Kefayat, A.; Rafienia, M.; Navid, S.; Karbasi, S.; Moshtaghian, J. In Vitro and in Vivo Performance of a Propolis-Coated Polyurethane Wound Dressing with High Porosity and Antibacterial Efficacy. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2019, 178, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Jiang, L.; Xu, C.; Kai, D.; Fan, X.; You, M.; Hui, C.M.; Wu, C.; Wu, Y.L.; Li, Z. Engineered Janus Amphipathic Polymeric Fiber Films with Unidirectional Drainage and Anti-Adhesion Abilities to Accelerate Wound Healing. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 421, 127725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahnavi, A.; Shahriari-Khalaji, M.; Hosseinpour, B.; Ahangarian, M.; Aidun, A.; Bungau, S.; Hassan, S.S.U. Evaluation of Cell Adhesion and Osteoconductivity in Bone Substitutes Modified by Polydopamine. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 10, 1057699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayet, J.C.; Fortier, G. High Water Content BSA-PEG Hydrogel for Controlled Release Device: Evaluation of the Drug Release Properties. J. Control. Release 1996, 38, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podhorská, B.; Chylíková-Krumbholcová, E.; Dvořáková, J.; Šlouf, M.; Kobera, L.; Pop-Georgievski, O.; Frejková, M.; Proks, V.; Janoušková, O.; Filipová, M.; et al. Soft Hydrogels with Double Porosity Modified with RGDS for Tissue Engineering. Macromol. Biosci. 2024, 24, 2300266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Astrain, C.; Guaresti, O.; González, K.; Santamaria-Echart, A.; Eceiza, A.; Corcuera, M.A.; Gabilondo, N. Click Gelatin Hydrogels: Characterization and Drug Release Behaviour. Mater. Lett. 2016, 182, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aduba, D.C.; Yang, H. Polysaccharide Fabrication Platforms and Biocompatibility Assessment as Candidate Wound Dressing Materials. Bioengineering 2017, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y. Understanding Bacterial Biofilms: From Definition to Treatment Strategies. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1137947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Yin, R.; Cheng, J.; Lin, J. Bacterial Biofilm Formation on Biomaterials and Approaches to Its Treatment and Prevention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Cui, S.; Yang, Q.; Song, X.; Wang, D.; Hu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y. AgNPs-Incorporated Nanofiber Mats: Relationship between AgNPs Size/Content, Silver Release, Cytotoxicity, and Antibacterial Activity. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 118, 111331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yao, Y.; Sullivan, N.; Chen, Y. Modeling the Primary Size Effects of Citrate-Coated Silver Nanoparticles on Their Ion Release Kinetics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 4422–4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiu, Z.M.; Zhang, Q.B.; Puppala, H.L.; Colvin, V.L.; Alvarez, P.J.J. Negligible Particle-Specific Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 4271–4275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino-Gómez, M.; Gil, J.; Perez, R.A.; Godoy-Gallardo, M. Polydopamine Incorporation Enhances Cell Differentiation and Antibacterial Properties of 3D-Printed Guanosine-Borate Hydrogels for Functional Tissue Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kord Forooshani, P.; Polega, E.; Thomson, K.; Bhuiyan, M.S.A.; Pinnaratip, R.; Trought, M.; Kendrick, C.; Gao, Y.; Perrine, K.A.; Pan, L.; et al. Antibacterial Properties of Mussel-Inspired Polydopamine Coatings Prepared by a Simple Two-Step Shaking-Assisted Method. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, M.J.; Sharifian Gh., M.; Wu, T.; Li, Y.; Chang, C.M.; Ma, J.; Dai, H.L. Determination of Bacterial Surface Charge Density via Saturation of Adsorbed Ions. Biophys. J. 2021, 120, 2461–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przekora, A.; Czechowska, J.; Pijocha, D.; Ślósarczyk, A.; Ginalska, G. Do Novel Cement-Type Biomaterials Reveal Ion Reactivity That Affects Cell Viability in Vitro? Cent. Eur. J. Biol. 2014, 9, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalicha, A.; Pałka, K.; Roguska, A.; Pisarek, M.; Belcarz, A. Polydopamine-Coated Curdlan Hydrogel as a Potential Carrier of Free Amino Group-Containing Molecules. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 256, 117524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Michalicha, A.; Vivcharenko, V.; Tomaszewska, A.; Kulpa-Greszta, M.; Budzyńska, B.; Fila, D.; Buxadera-Palomero, J.; Krawczyńska, A.; Canal, C.; Kołodyńska, D.; et al. Poly(levodopa)-Modified β-(1 → 3)-D-Glucan Hydrogel Enriched with Triangle-Shaped Nanoparticles as a Biosafe Matrix with Enhanced Antibacterial Potential. Molecules 2026, 31, 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010181

Michalicha A, Vivcharenko V, Tomaszewska A, Kulpa-Greszta M, Budzyńska B, Fila D, Buxadera-Palomero J, Krawczyńska A, Canal C, Kołodyńska D, et al. Poly(levodopa)-Modified β-(1 → 3)-D-Glucan Hydrogel Enriched with Triangle-Shaped Nanoparticles as a Biosafe Matrix with Enhanced Antibacterial Potential. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):181. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010181

Chicago/Turabian StyleMichalicha, Anna, Vladyslav Vivcharenko, Anna Tomaszewska, Magdalena Kulpa-Greszta, Barbara Budzyńska, Dominika Fila, Judit Buxadera-Palomero, Agnieszka Krawczyńska, Cristina Canal, Dorota Kołodyńska, and et al. 2026. "Poly(levodopa)-Modified β-(1 → 3)-D-Glucan Hydrogel Enriched with Triangle-Shaped Nanoparticles as a Biosafe Matrix with Enhanced Antibacterial Potential" Molecules 31, no. 1: 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010181

APA StyleMichalicha, A., Vivcharenko, V., Tomaszewska, A., Kulpa-Greszta, M., Budzyńska, B., Fila, D., Buxadera-Palomero, J., Krawczyńska, A., Canal, C., Kołodyńska, D., Belcarz-Romaniuk, A., & Pązik, R. (2026). Poly(levodopa)-Modified β-(1 → 3)-D-Glucan Hydrogel Enriched with Triangle-Shaped Nanoparticles as a Biosafe Matrix with Enhanced Antibacterial Potential. Molecules, 31(1), 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010181