Bromo Analogues of Active 3,4,5,4′-Tetramethoxy-trans-stilbene (DMU-212)—A New Path of Research to Anticancer Agents

Abstract

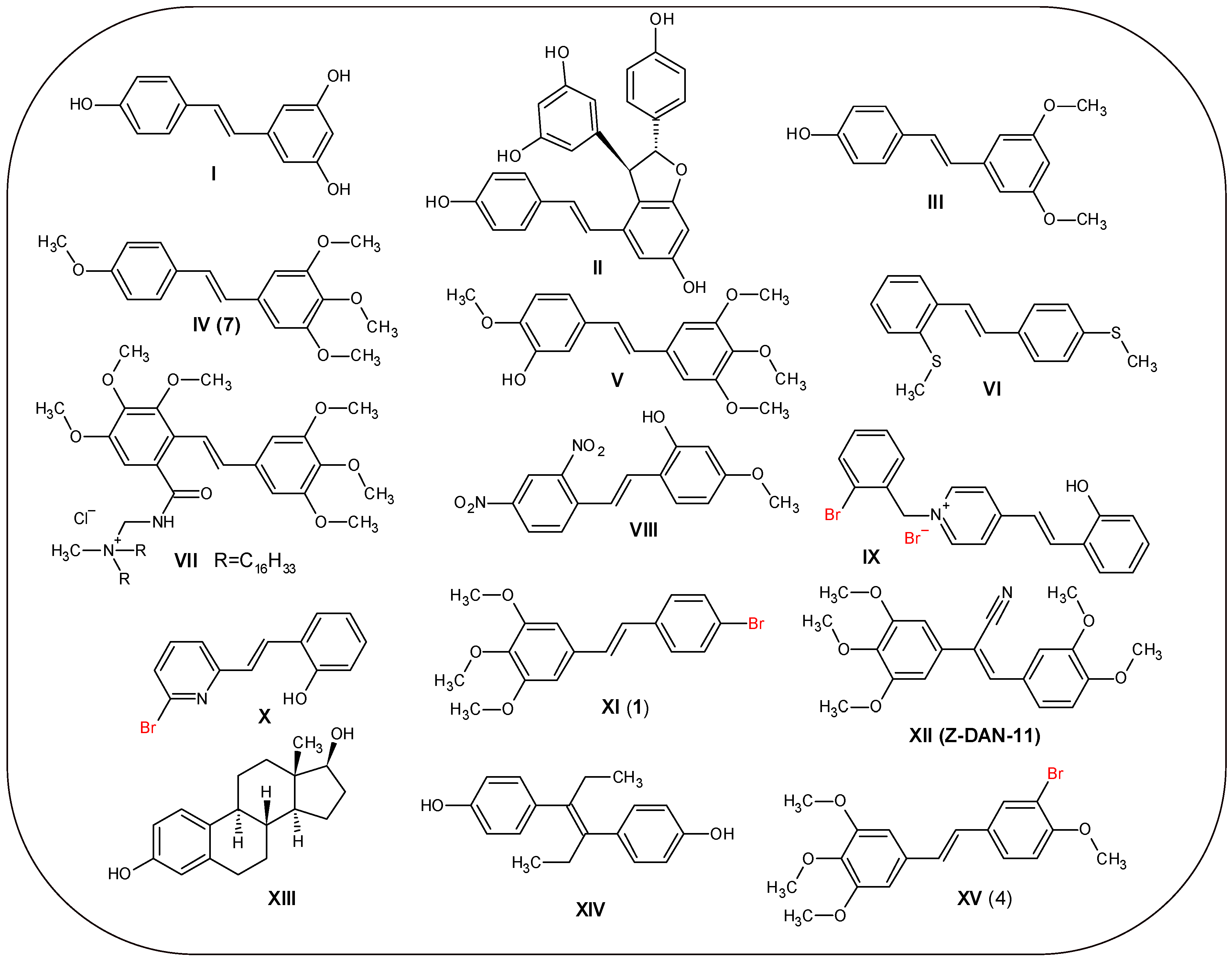

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis

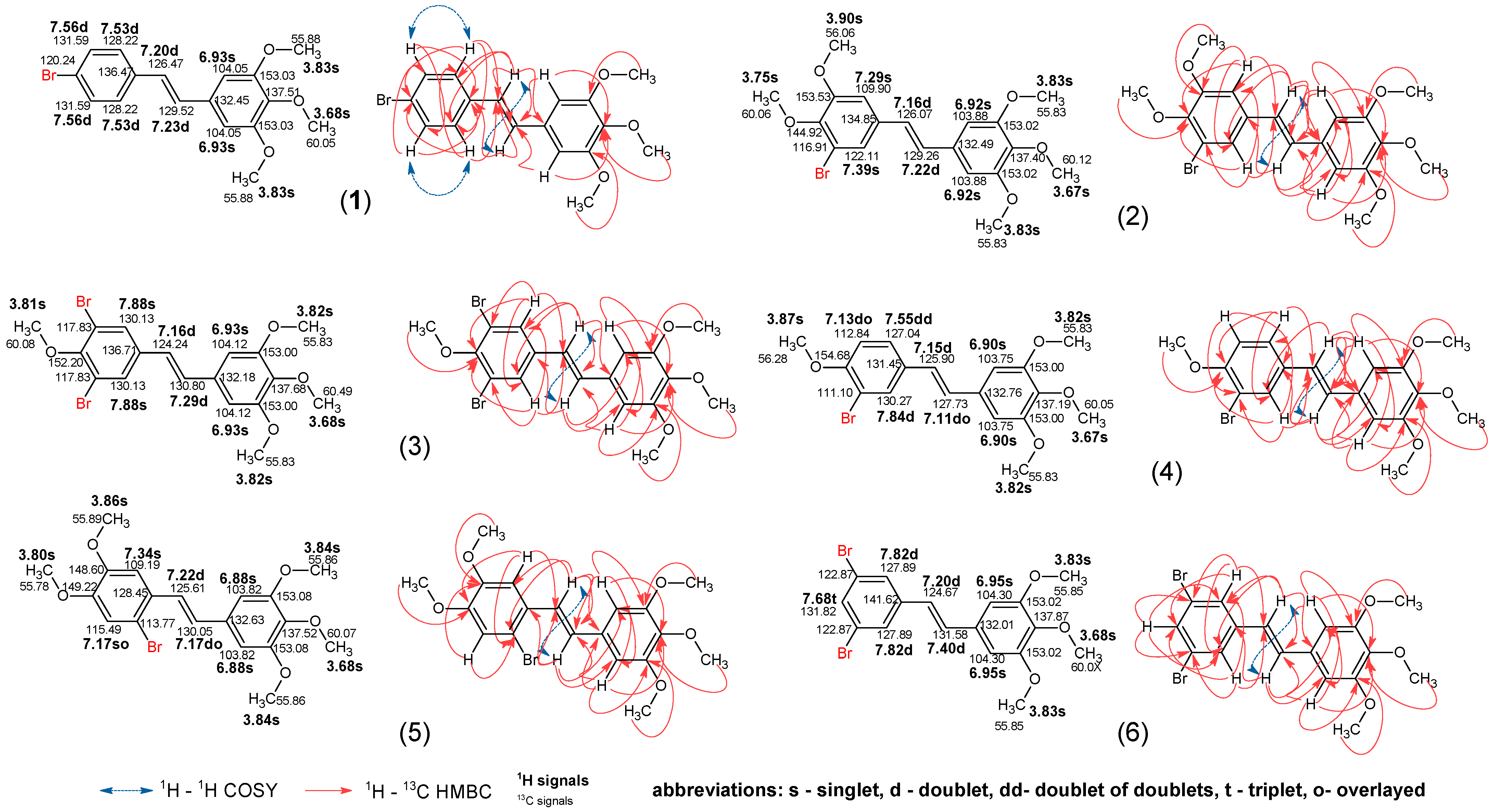

2.2. NMR Study

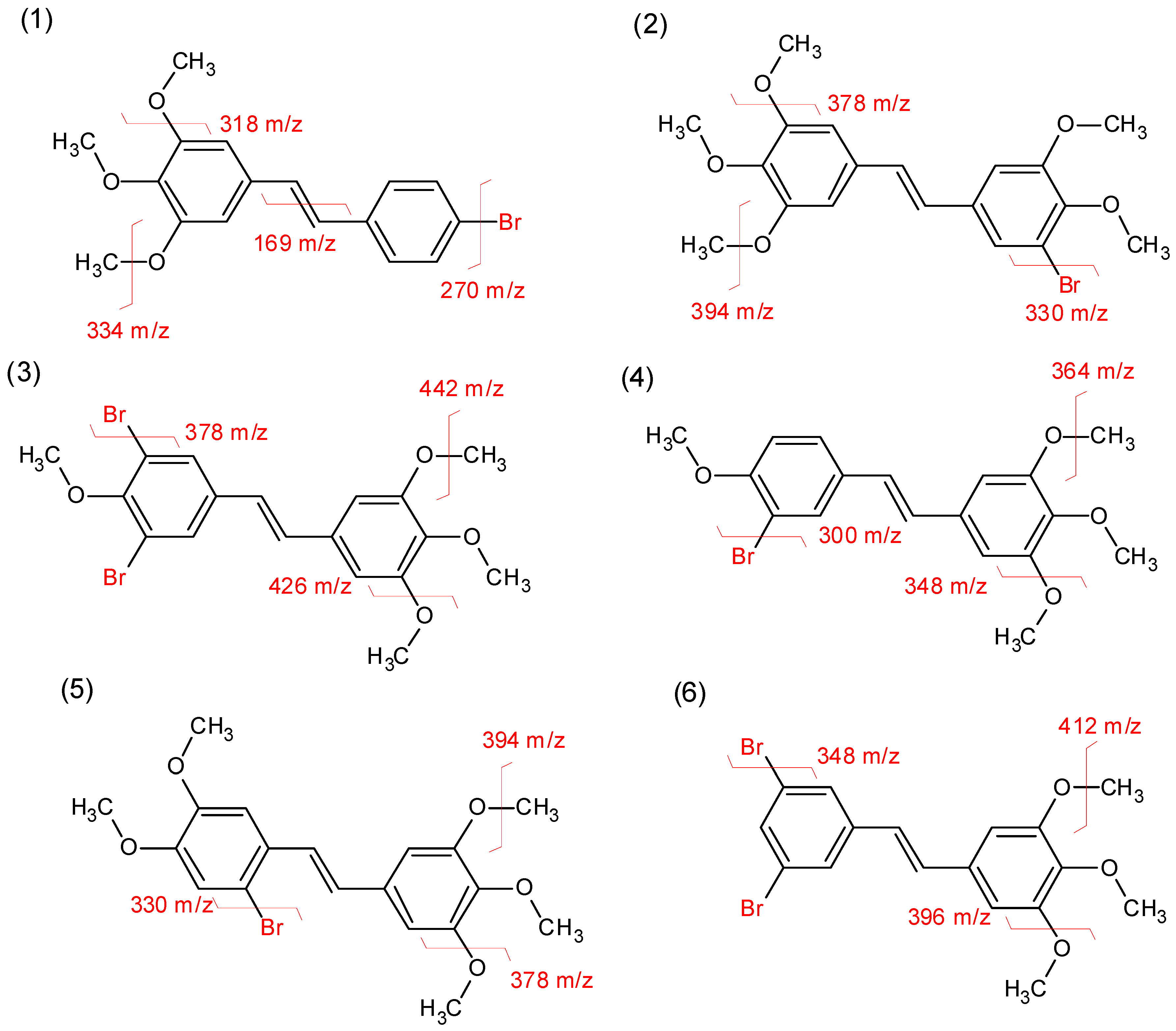

2.3. Mass Spectrometry

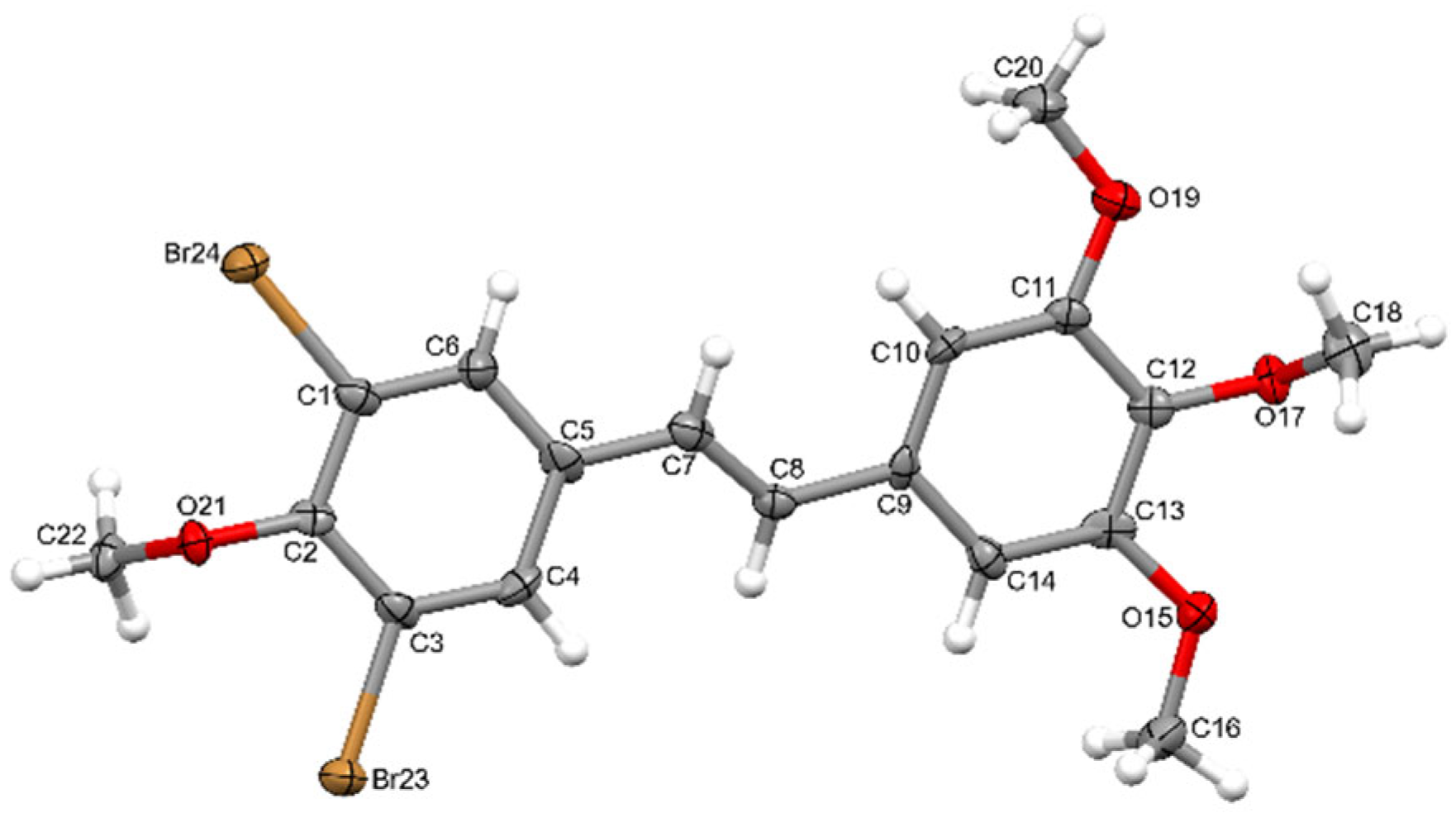

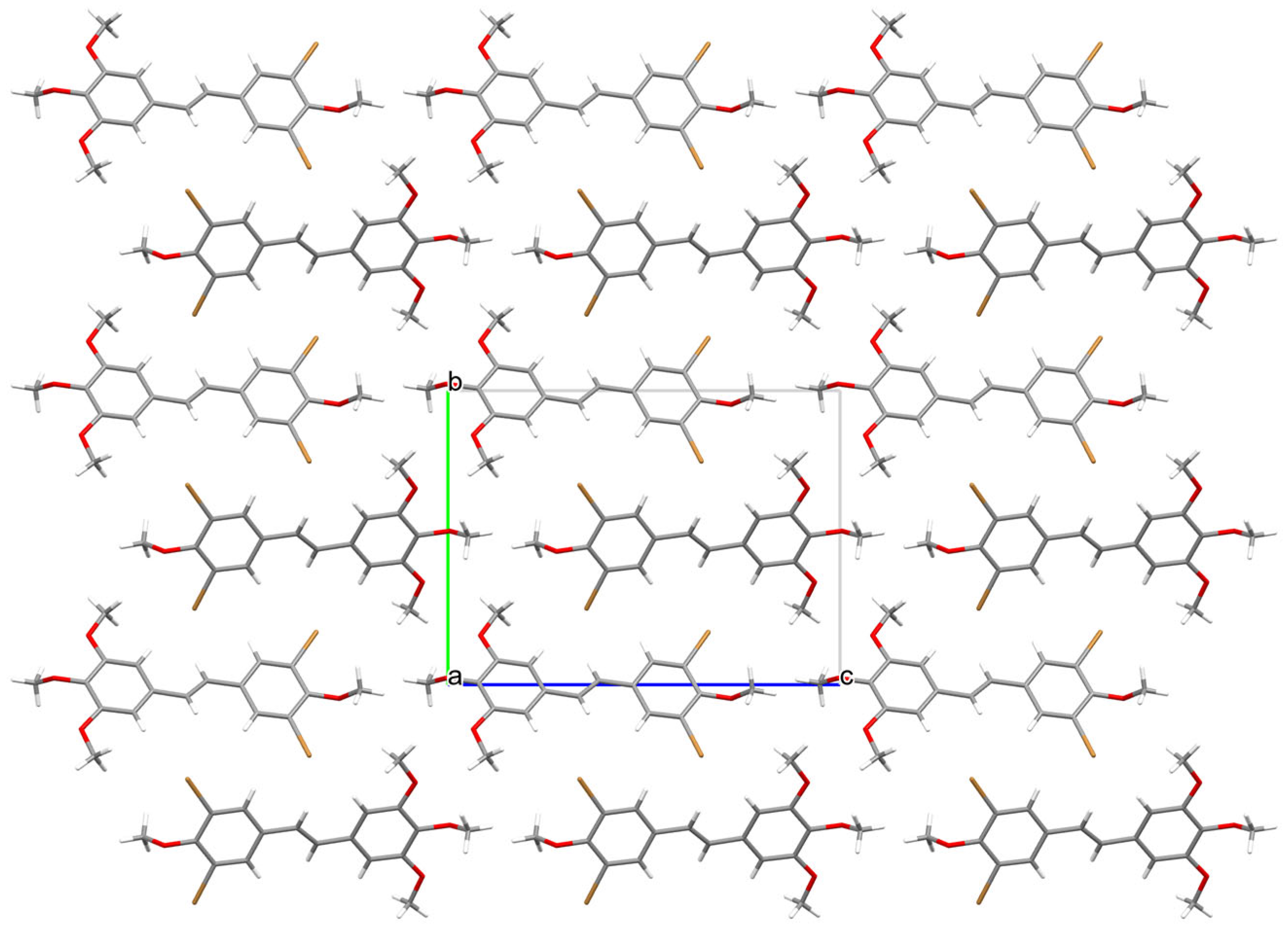

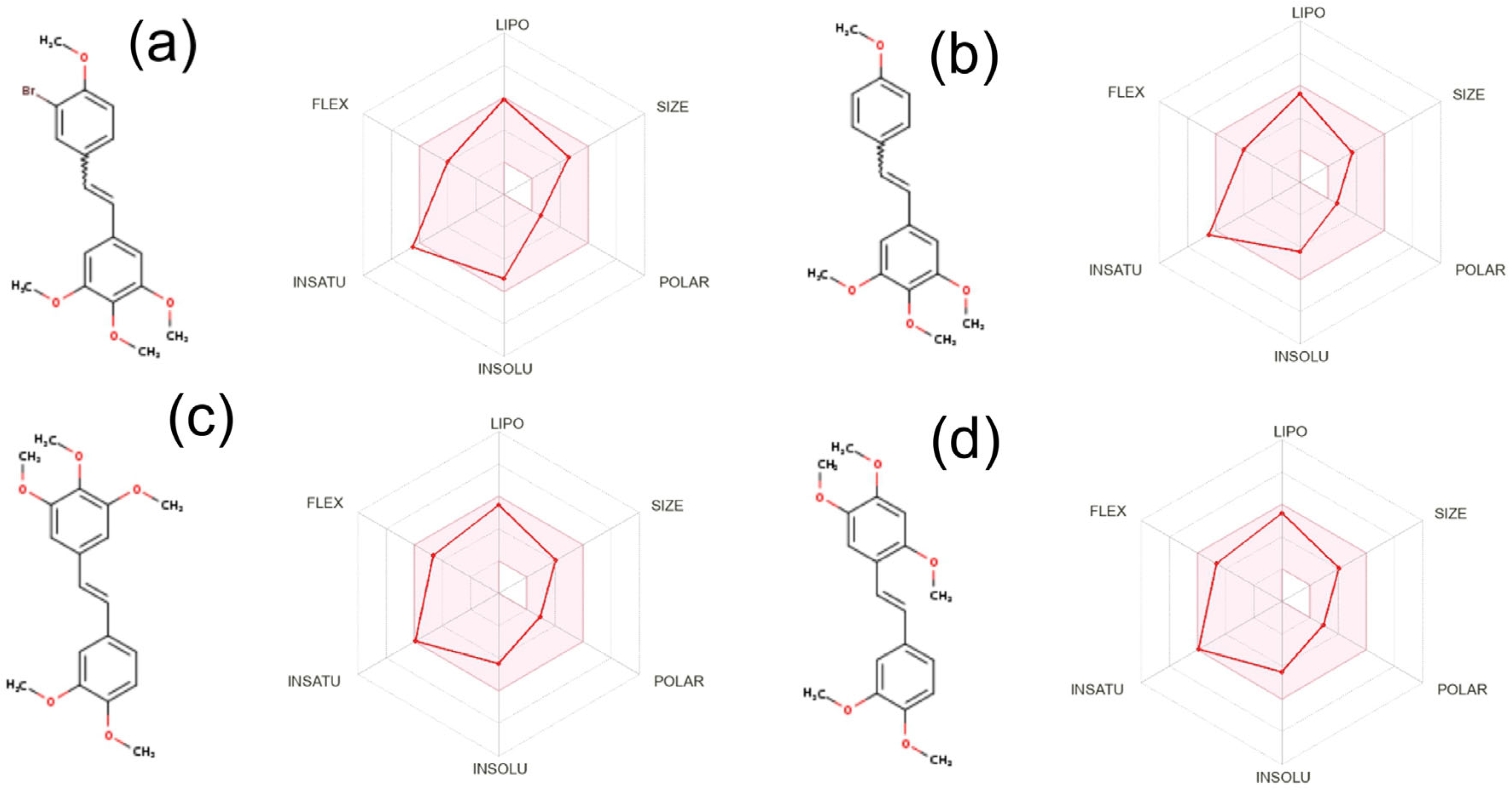

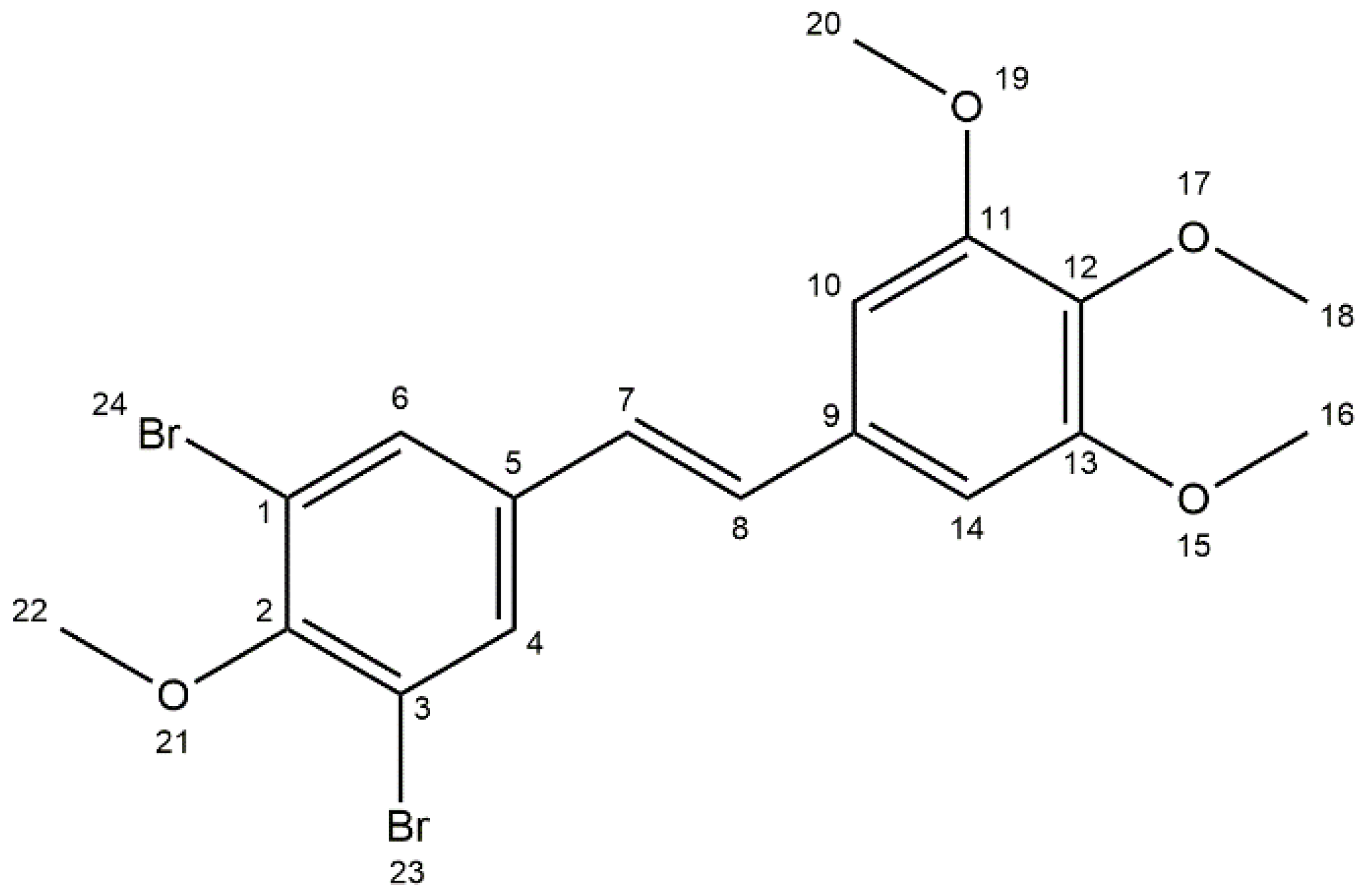

2.4. X-Ray Diffraction Studies

2.5. Biological Activity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Crystallographic Measurements

3.2. Synthesis of Trans-Stilbenes Derivatives

- (1)

- 4-bromo-3′,4′,5′-trimethoxy-trans-stilbene

- (2)

- 3-bromo-3′,4′,5′,4,5-pentamethoxy-trans-stilbene

- (3)

- 3,5-dibromo-3′,4′,5′,4-tetramethoxy-trans-stilbene

- (4)

- 3-bromo-3′,4′,5′,4-tetramethoxy-trans-stilbene

- (5)

- 2-bromo-3′,4′,5′,4,5-pentamethoxy-trans-stilbene

- (6)

- 3,5-dibromo-3′,4′,5′-trimethoxy-trans-stilbene

3.3. Cytotoxic Activity of the Tested Compounds

3.4. DNA Intercalation Assay (Methyl Green Displacement Method)

3.5. The Fluorescent Microscopy of Jurkat Cells

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO MONICA Project Principal Investigators. The World Health Organization Monica Project (Monitoring Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease): A Major International Collaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1988, 41, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragopoulou, E.; Antonopoulou, S. The French Paradox Three Decades Later: Role of Inflammation and Thrombosis. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 510, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renaud, S.; Guéguen, R.; Schenker, J.; d’Houtaud, A. Alcohol and Mortality in Middle-Aged Men from Eastern France. Epidemiology 1998, 9, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teka, T.; Zhang, L.; Ge, X.; Li, Y.; Han, L.; Yan, X. Stilbenes: Source Plants, Chemistry, Biosynthesis, Pharmacology, Application and Problems Related to Their Clinical Application-A Comprehensive Review. Phytochemistry 2022, 197, 113128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapeshi, A.; Benarroch, J.M.; Clarke, D.J.; Waterfield, N.R. Iso-Propyl Stilbene: A Life Cycle Signal? Microbiology 2019, 165, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirén, H. Current Research on Determination of Medically Valued Stilbenes and Stilbenoids from Spruce and Pine with Chromatographic and Spectrometric Methods—A Review. J. Chromatogr. Open 2024, 6, 100169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Jin, L.; Liu, H.; Hua, Z. Stilbenes: A Promising Small Molecule Modulator for Epigenetic Regulation in Human Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1326682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecyna, P.; Wargula, J.; Murias, M.; Kucinska, M. More than Resveratrol: New Insights into Stilbene-Based Compounds. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Y.K.; Lau, K.M.; Mobley, J.; Jiang, Z.; Ho, S.M. Overexpression of Cytochrome P450 1A1 and Its Novel Spliced Variant in Ovarian Cancer Cells: Alternative Subcellular Enzyme Compartmentation May Contribute to Carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 3726–3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Józkowiak, M.; Kobylarek, D.; Bryja, A.; Gogola-Mruk, J.; Czajkowski, M.; Skupin-Mrugalska, P.; Kempisty, B.; Spaczyński, R.Z.; Piotrowska-Kempisty, H. Steroidogenic Activity of Liposomal Methylated Resveratrol Analog 3,4,5,4′-Tetramethoxystilbene (DMU-212) in Human Luteinized Granulosa Cells in a Primary Three-Dimensional in Vitro Model. Endocrine 2023, 82, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piotrowska-Kempisty, H.; Rucinski, M.; Borys, S.; Kucinska, M.; Kaczmarek, M.; Zawierucha, P.; Wierzchowski, M.; Lazewski, D.; Murias, M.; Jodynis-Liebert, J. 3′-Hydroxy-3,4,5,4′-Tetramethoxystilbene, the Metabolite of Resveratrol Analogue DMU-212, Inhibits Ovarian Cancer Cell Growth in Vitro and in a Mice Xenograft Model. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobylka, P.; Kucinska, M.; Kujawski, J.; Lazewski, D.; Wierzchowski, M.; Murias, M. Resveratrol Analogues as Selective Estrogen Signaling Pathway Modulators: Structure–Activity Relationship. Molecules 2022, 27, 6973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wierzchowski, M.; Dutkiewicz, Z.; Gielara-Korzańska, A.; Korzański, A.; Teubert, A.; Teżyk, A.; Stefański, T.; Baer-Dubowska, W.; Mikstacka, R. Synthesis, Biological Evaluation and Docking Studies of Trans-Stilbene Methylthio Derivatives as Cytochromes P450 Family 1 Inhibitors. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2017, 90, 1226–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousuf, M.; Jinka, S.; Adhikari, S.S.; Banerjee, R. Methoxy-Enriched Cationic Stilbenes as Anticancer Therapeutics. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 98, 103719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbicz, D.; Mielecki, D.; Wrzesinski, M.; Pilzys, T.; Marcinkowski, M.; Piwowarski, J.; Debski, J.; Palak, E.; Szczecinski, P.; Krawczyk, H.; et al. Evaluation of Anti-Cancer Activity of Stilbene and Methoxydibenzo[b,f] Oxepin Derivatives. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2018, 18, 706–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potapskyi, E.; Kustrzyńska, K.; Łażewski, D.; Skupin-Mrugalska, P.; Lesyk, R.; Wierzchowski, M. Introducing Bromine to the Molecular Structure as a Strategy for Drug Design. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 93, e1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Gao, X.; Chen, X.; Li, L.; Li, G.; Liu, C.; Miao, Y.; Wang, R.; Hu, K. Radiopharmaceuticals and Their Applications in Medicine. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Tian, X.; Meccia, S.A.; Zhou, J. Highlights on U.S. FDA-Approved Halogen-Containing Drugs in 2024. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 287, 117380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hairani, R.; Chavasiri, W. Synthesis of Promising Brominated Flavonoids as Antidiabetic and Anti-Glycation Agents. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluska, M.; Jabłońska, J.; Prukała, W. Analytics, Properties and Applications of Biologically Active Stilbene Derivatives. Molecules 2023, 28, 4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippis, B.; Ammazzalorso, A.; Amoroso, R.; Giampietro, L. Stilbene Derivatives as New Perspective in Antifungal Medicinal Chemistry. Drug Dev. Res. 2019, 80, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, G.C.; Prakash, S.S.; Diwakar, L. Stilbene Heterocycles: Synthesis, Antimicrobial, Antioxidant and Anticancer Activities. Pharma Innov. J. 2015, 3, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.J.; Min, H.Y.; Joo Park, H.; Chung, H.J.; Kim, S.; Nam Han, Y.; Lee, S.K. G2/M Cell Cycle Arrest and Induction of Apoptosis by a Stilbenoid, 3,4,5-Trimethoxy-4′-Bromo-Cis-Stilbene, in Human Lung Cancer Cells. Life Sci. 2004, 75, 2829–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chillemi, R.; Sciuto, S.; Spatafora, C.; Tringali, C. Anti-Tumor Properties of Stilbene-Based Resveratrol Analogues: Recent Results. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2007, 2, 1934578X0700200419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, G.R.; Rhodes, M.R.; Herald, D.L.; Hamel, E.; Schmidt, J.M.; Pettit, R.K. Antineoplastic Agents. 445. Synthesis and Evaluation of Structural Modifications of (Z)- and (E)-Combretastatin A-4. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 4087–4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murias, M.; Handler, N.; Erker, T.; Pleban, K.; Ecker, G.; Saiko, P.; Szekeres, T.; Jäger, W. Resveratrol Analogues as Selective Cyclooxygenase-2 Inhibitors: Synthesis and Structure-Activity Relationship. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004, 12, 5571–5578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piekuś-Słomka, N.; Małecka, M.; Wierzchowski, M.; Kupcewicz, B. Systematic Study of Solid-State Fluorescence and Molecular Packing of Methoxy-Trans-Stilbene Derivatives, Exploration of Weak Intermolecular Interactions Based on Hirshfeld Surface Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganga, R.G.; Rama, R.G.; Gottumukkala, S.V.; Somepalli, V. Novel Resveratrol Analogs. Patent No. wo2004/000302, 31 December 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mikstacka, R.; Wierzchowski, M.; Dutkiewicz, Z.; Gielara-Korzańska, A.; Korzański, A.; Teubert, A.; Sobiak, S.; Baer-Dubowska, W. 3,4,2′-Trimethoxy-Trans-Stilbene-a Potent CYP1B1 Inhibitor. Medchemcomm 2014, 5, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowska, H.; Myszkowski, K.; Ziółkowska, A.; Kulcenty, K.; Wierzchowski, M.; Kaczmarek, M.; Murias, M.; Kwiatkowska-Borowczyk, E.; Jodynis-Liebert, J. Resveratrol Analogue 3,4,4′,5-Tetramethoxystilbene Inhibits Growth, Arrests Cell Cycle and Induces Apoptosis in Ovarian SKOV-3 and A-2780 Cancer Cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2012, 263, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Filippis, B.; Ammazzalorso, A.; Fantacuzzi, M.; Giampietro, L.; Maccallini, C.; Amoroso, R. Anticancer Activity of Stilbene-Based Derivatives. ChemMedChem 2017, 12, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A Free Web Tool to Evaluate Pharmacokinetics, Drug-Likeness and Medicinal Chemistry Friendliness of Small Molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. ILOGP: A Simple, Robust, and Efficient Description of n -Octanol/Water Partition Coefficient for Drug Design Using the GB/SA Approach. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014, 54, 3284–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, P.K.; Mahata, B.; Santra, A.; Chakraborty, S.; Ghosh, Z.; Raha, S.; Misra, A.K.; Biswas, K.; Jana, K. Inhibition of Cancer Progression by a Novel Trans-Stilbene Derivative through Disruption of Microtubule Dynamics, Driving G2/M Arrest, and P53-Dependent Apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruker. SAINT, V8.41; Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, L.; Herbst-Irmer, R.; Sheldrick, G.M.; Stalke, D. Comparison of Silver and Molybdenum Microfocus X-Ray Sources for Single-Crystal Structure Determination. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2015, 48, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT—Integrated Space-Group and Crystal-Structure Determination. Found. Adv. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal Structure Refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macrae, C.F.; Bruno, I.J.; Chisholm, J.A.; Edgington, P.R.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Rodriguez-Monge, L.; Taylor, R.; van de Streek, J.; Wood, P.A. Mercury CSD 2.0—New Features for the Visualization and Investigation of Crystal Structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008, 41, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groom, C.R.; Bruno, I.J.; Lightfoot, M.P.; Ward, S.C. The Cambridge Structural Database. Struct. Sci. Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2016, 72, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finiuk, N.; Kryshchyshyn-Dylevych, A.; Holota, S.; Klyuchivska, O.; Kozytskiy, A.; Karpenko, O.; Manko, N.; Ivasechko, I.; Stoika, R.; Lesyk, R. Novel Hybrid Pyrrolidinedione-Thiazolidinones as Potential Anticancer Agents: Synthesis and Biological Evaluation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 238, 114422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filak, L.K.; Mü, G.; Jakupec, M.A.; Heffeter, P.; Berger, W.; Arion, V.B.; Keppler, B.K.; Heffeter, P.; Berger, Á.W.; Jakupec, M.A.; et al. Organometallic Indolo[3,2-c]Quinolines versus Indolo[3,2-d]Benzazepines: Synthesis, Structural and Spectroscopic Characterization, and Biological Efficacy. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 15, 903–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androutsopoulos, V.P.; Ruparelia, K.C.; Papakyriakou, A.; Filippakis, H.; Tsatsakis, A.M.; Spandidos, D.A. Anticancer Effects of the Metabolic Products of the Resveratrol Analogue, DMU-212: Structural Requirements for Potency. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 2586–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefański, T.; Mikstacka, R.; Kurczab, R.; Dutkiewicz, Z.; Kucińska, M.; Murias, M.; Zielińska-Przyjemska, M.; Cichocki, M.; Teubert, A.; Kaczmarek, M.; et al. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Novel Combretastatin A-4 Thio Derivatives as Microtubule Targeting Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 144, 797–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound | Substituents | Yield [%] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ring B (Position in Ring) | Ring A (Position in Ring) | |||||||

| R1 (Pos.2) | R2 (Pos.3) | R3 (Pos.4) | R4 (Pos.5) | R1 (Pos.2) | R2 (Pos.3) | R3 (Pos.2/6) | ||

| 1 | -H | -H | -Br | -H | -H | -OCH3 | -H | 55 |

| 2 | -H | -Br | -OCH3 | -OCH3 | -H | -OCH3 | -H | 56 |

| 3 | -H | -Br | -OCH3 | -Br | -H | -OCH3 | -H | 54 |

| 4 | -H | -Br | -OCH3 | -H | -H | -OCH3 | -H | 59 |

| 5 | -Br | -H | -OCH3 | -OCH3 | -H | -OCH3 | -H | 63 |

| 6 | -H | -Br | -H | -Br | -H | -OCH3 | -H | 19 |

| 7 | -H | -H | -OCH3 | -H | -H | -OCH3 | -H | 53 * |

| 8 | -H | -OCH3 | -OCH3 | -H | -H | -OCH3 | -H | 44 * |

| 9 | -H | -OCH3 | -OCH3 | -OCH3 | -H | -OCH3 | -H | 45 * |

| 10 | -H | -OCH3 | -OCH3 | -H | -OCH3 | -H | -H | 53 * |

| 11 | -H | -OCH3 | -OCH3 | -H | -H | -H | -OCH3 | 40 * |

| 12 | -H | -OCH3 | -H | -OCH3 | -H | -OCH3 | -H | 57 * |

| Compound | Tumour Cell Lines [µM] | Pseudo-Normal Cell Lines [µM] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jurkat Human Acute T-Cell Leukaemia | U251 Human Malignant Glioblastoma | HT-29 Human Colorectal Carcinoma | Balb-3T3 Mice Fibro- Blast | J744.2 Mice Macrophage-Like Cells | |

| 1 | 2.26 | >100 | >100 | 3.20 | 6.63 |

| 2 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 72.79 | 7.93 |

| 3 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 76.36 | 20.39 |

| 4 | 0.76 | >100 | >100 | 2.85 | 5.21 |

| 5 | 68.55 | >100 | >100 | 51.74 | 71.13 |

| 6 | 65.34 | >100 | >100 | 3.75 | 9.97 |

| 7 | 0.65 | >100 | >100 | 2.79 | 0.83 |

| 8 | 0.82 | >100 | >100 | 5.04 | 3.83 |

| 9 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 84.83 |

| 10 | 8.95 | >100 | >100 | >100 | 91.63 |

| 11 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 12 | 67.61 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| CCDC Number | 2499084 |

| Empirical formula | C18H18Br2O4 |

| Formula weight | 458.14 |

| Temperature [K] | 100 |

| Crystal system | monoclinic |

| Space group (number) | (4) |

| a [Å] | 4.2837(5) |

| b [Å] | 12.3535(14) |

| c [Å] | 16.562(2) |

| α [°] | 90 |

| β [°] | 96.420(6) |

| γ [°] | 90 |

| Volume [Å3] | 870.95(18) |

| Z | 2.0 |

| ρcalc [g/cm3] | 1.747 |

| μ [mm−1] | 4.673 |

| F(000) | 456 |

| Crystal size [mm3] | 0.037 × 0.044 × 0.269 |

| Crystal colour | colourless |

| Crystal shape | post |

| Radiation | Mo Kα (λ = 0.71073 Å) |

| 2θ range [°] | 4.12 to 50.88 (0.83 Å) |

| Index ranges | −5 ≤ h ≤ 5 −14 ≤ k ≤ 14 −19 ≤ l ≤ 19 |

| Reflections collected | 12,582 |

| Independent reflections | 3123 Rint = 0.0232 Rsigma = 0.0233 |

| Completeness to θ = 25.242° | 99.7 |

| Data/Restraints/Parameters | 3123/1/221 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.125 |

| Final R indexes [I ≥ 2σ(I)] | R1 = 0.0455 wR2 = 0.1002 |

| Final R indexes [all data] | R1 = 0.0496 wR2 = 0.1035 |

| Largest peak/hole [eÅ−3] | 0.65/−0.56 |

| Flack X parameter | 0.480(3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Łażewski, D.; Korzańska, G.; Popenda, Ł.; Chmaj-Wierzchowska, K.; Korzański, A.; Potapskyi, E.; Myszkiewicz, J.; Gielara-Korzańska, A.; Zgoła-Grześkowiak, A.; Finiuk, N.; et al. Bromo Analogues of Active 3,4,5,4′-Tetramethoxy-trans-stilbene (DMU-212)—A New Path of Research to Anticancer Agents. Molecules 2025, 30, 4788. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244788

Łażewski D, Korzańska G, Popenda Ł, Chmaj-Wierzchowska K, Korzański A, Potapskyi E, Myszkiewicz J, Gielara-Korzańska A, Zgoła-Grześkowiak A, Finiuk N, et al. Bromo Analogues of Active 3,4,5,4′-Tetramethoxy-trans-stilbene (DMU-212)—A New Path of Research to Anticancer Agents. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4788. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244788

Chicago/Turabian StyleŁażewski, Dawid, Gabriela Korzańska, Łukasz Popenda, Karolina Chmaj-Wierzchowska, Artur Korzański, Eduard Potapskyi, Julian Myszkiewicz, Agnieszka Gielara-Korzańska, Agnieszka Zgoła-Grześkowiak, Nataliya Finiuk, and et al. 2025. "Bromo Analogues of Active 3,4,5,4′-Tetramethoxy-trans-stilbene (DMU-212)—A New Path of Research to Anticancer Agents" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4788. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244788

APA StyleŁażewski, D., Korzańska, G., Popenda, Ł., Chmaj-Wierzchowska, K., Korzański, A., Potapskyi, E., Myszkiewicz, J., Gielara-Korzańska, A., Zgoła-Grześkowiak, A., Finiuk, N., Kozak, Y., Ivasechko, I., Lesyk, R., Kuźmińska, J., Goslinski, T., & Wierzchowski, M. (2025). Bromo Analogues of Active 3,4,5,4′-Tetramethoxy-trans-stilbene (DMU-212)—A New Path of Research to Anticancer Agents. Molecules, 30(24), 4788. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244788