Characterization of Steam Volatiles and Evaluation of the Antioxidant Properties of Different Extracts from Leaves and Roots of Aegopodium podagraria L.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

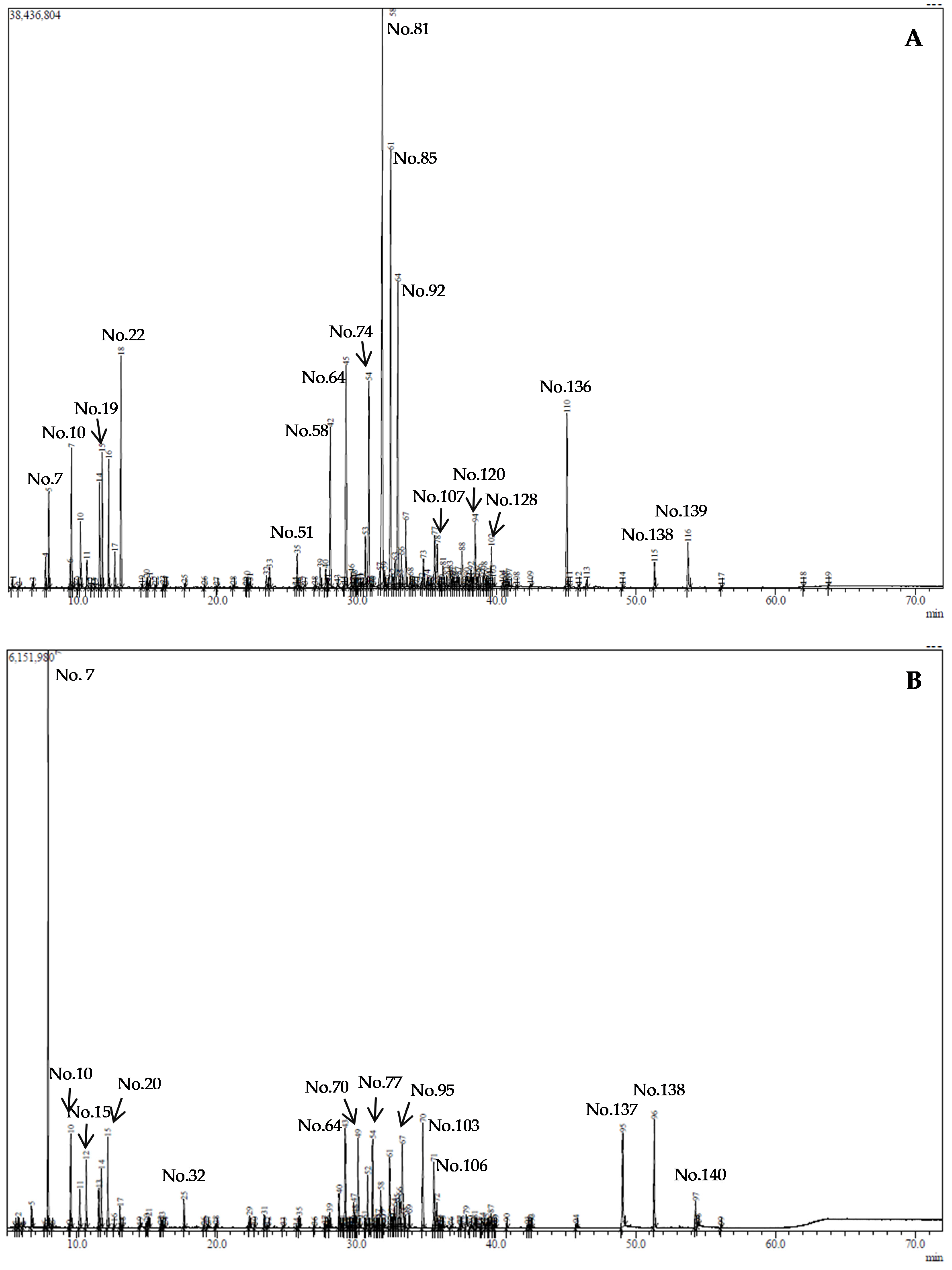

2.1. The Composition of Essential Oils (EOs)

| No # | Compound A | KI Calc. B | KI Lit. C | GLEO | GREO | Odour Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (E)-2-Hexenal | 847 | 855 | 0.14 ± 0.00 E | green, leaf 1; sharp, fresh, leafy, green, clean, fruity, herbal, spicy, herbal 2 | |

| 2 | (2E)-Hexenol * | 866 | 862 | tr F | green, leaf, walnut 1; fresh, fatty, green, fruity, vegetable, leafy, herbal 2 | |

| 3 | n-Hexanol | 869 | 870 | tr | 0.32 ± 0.02 | resin, flower, green 1; ethereal, fusel, oily, fruity, alcoholic, sweet, green 2 |

| 4 | n-Nonane | 900 | 900 | tr | 0.98 ± 0.01 | alkane 1 |

| 5 | Heptanal | 901 | 902 | 0.12 ± 0.00 | fat, citrus, rancid 1; fresh, aldehydic, fatty, green, herbal, cognac, ozone 2 | |

| 6 | α-Thujene | 929 | 930 | 0.48 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | wood, green, herb 1; woody, green, herbal 2 |

| 7 | α-Pinene | 936 | 939 | 1.60 ± 0.02 | 19.24 ± 0.09 | pine, turpentine1; fresh, camphoreous, sweet, pine, earthy, woody 2 |

| 8 | Camphene | 954 | 954 | tr | camphor 1; woody, herbal, fir, needle, camphoreous, terpenic 2 | |

| 9 | Sabinene | 975 | 975 | 0.42 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | pepper, turpentine, wood 1; wood, spicy, citrus, terpenic, green, oily, camphoreous 2 |

| 10 | β-Pinene | 978 | 979 | 2.42 ± 0.02 | 3.22 ± 0.02 | pine, resin, turpentine 1; dry, woody, resinous, pine, hay, green, eucalyptus, camphoreous 2 |

| 11 | 1-Octen-3-ol | 981 | 979 | tr | mushroom 1 | |

| 12 | 6-Methyl-5-hepten-2-one | 988 | 985 | 0.12 ± 0.00 | citrus, green, musty, lemongrass, apple 2 | |

| 13 | Myrcene | 992 | 990 | 1.14 ± 0.02 | 1.33 ± 0.01 | balsamic, must, spice 1; terpenic, herbal, woody, rose, celery, carrot 2 |

| 14 | 3-Octanol | 992 | 991 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | moss, nut, mushroom 1; earthy, mushroom, herbal, melon, citrus, woody, spicy, minty 2 | |

| 15 | n-Octanal | 1003 | 998 | 0.62 ± 0.01 | 2.35 ± 0.02 | fat, soap, lemon, green 1; aldehydic, waxy, citrus, orange, peel, green, herbal, fresh, fatty 2 |

| 16 | (2E,4E)-Heptadienal * | 1010 | 1007 | tr | nut, fat 1; fatty, green, oily, aldehydic, vegetable 2 | |

| 17 | α-Terpinene | 1018 | 1017 | tr | lemon 1; woody, terpenic, lemon, herbal, medicinal, citrus 2 | |

| 18 | p-Cymene | 1026 | 1024 | 1.93 ± 0.01 | 1.33 ± 0.01 | solvent, gasoline, citrus 1; fresh, citrus, terpenic, woody, spicy 2 |

| 19 | Limonene | 1031 | 1029 | 2.45 ± 0.03 | 2.04 ± 0.01 | lemon, orange 1; citrus, orange, fresh, sweet 2 |

| 20 | (Z)-β-Ocimene | 1042 | 1037 | 2.29 ± 0.01 | 3.11 ± 0.01 | citrus, herb, flower 1; warm, floral, herbal, sweet 2 |

| 21 | (E)-β-Ocimene | 1052 | 1050 | 0.65 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | sweet, herb 1 |

| 22 | γ-Terpinene | 1062 | 1059 | 4.54 ± 0.04 | 0.77 ± 0.03 | gasoline, turpentine 1; oily, woody, terpenic, lemon, lime, tropical, herbal 2 |

| 23 | Terpinolene | 1090 | 1088 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | fresh, woody, sweet, pine, citrus 2 |

| 24 | 2-Nonanone | 1093 | 1090 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | hot milk, soap, green 1; fresh, sweet, green, weedy, earthy, herbal 2 |

| 25 | Linalool | 1099 | 1096 | 0.19 ± 0.00 | tr | flower, lavender 1; citrus, orange, floral, terpenic, waxy, rose 2 |

| 26 | n-Undecane * | 1100 | 1100 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | alkane 1 | |

| 27 | n-Nonanal | 1104 | 1100 | 0.13 ± 0.00 | 0.38 ± 0.00 | fat, citrus, green 1; waxy, aldehydic, citrus, fresh, green, lemon peel, cucumber, fatty 2 |

| 28 | 1-Octen-3-yl acetate * | 1114 | 1112 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | fresh, green, herbal, lavender, fruity, oily 2 | |

| 29 | 3-Octanol acetate * | 1125 | 1123 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | fresh, bergamot, woody, green, grapefruit, rose, apple, minty 2 | |

| 30 | α-Campholenal | 1127 | 1126 | 0.35 ± 0.02 | herbal, green, woody, amber, leafy 2 | |

| 31 | allo-Ocimene | 1131 | 1132 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | sweet, floral, nut, skin, peppery, herbal, tropical 2 |

| 32 | (2E)-Nonen-1-al | 1161 | 1161 | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 1.04 ± 0.01 | cucumber, fat, green 1; fatty, green, cucumber, aldehydic, citrus 2 |

| 33 | Terpinen-4-ol | 1177 | 1177 | tr | turpentine, nutmeg, must 1; woody, mentholic, citrus, terpenic, spicy 2 | |

| 34 | Naphthalene * | 1181 | 1181 | tr | tar 1 | |

| 35 | α-Terpineol | 1190 | 1188 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | oil, anise, mint 1; pine, woody, resinous, cooling, lemon, lime, citrus, floral 2 |

| 36 | Myrtenol | 1195 | 1195 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | woody, pine, balsamic, sweet, minty, medicinal 2 | |

| 37 | p-Cymen-9-ol * | 1208 | 1205 | tr | ||

| 38 | Octanol acetate * | 1210 | 1213 | 0.12 ± 0.00 | green, earthy, mushroom, herbal, waxy, fruity, apple 2 | |

| 39 | (E)-Carveol | 1214 | 1216 | tr | caraway, solvent 1 | |

| 40 | Thymol methyl ether | 1237 | 1235 | tr | woody, smoky, burnt 2 | |

| 41 | Geraniol | 1257 | 1252 | tr | rose, geranium 1; sweet, floral, fruity, rose, waxy, citrus 2 | |

| 42 | Linalool acetate | 1259 | 1257 | 0.14 ± 0.00 | sweet, fruit 1; sweet, green, floral, spicy, clean, woody, terpenic, citrus 2 | |

| 43 | (E)-Myrtanol * | 1260 | 1261 | tr | ||

| 44 | (2E)-Decenal | 1263 | 1263 | 0.11 ± 0.00 | 0.47 ± 0.01 | orange, tallow 1; waxy, fatty, earthy, green, cilantro, mushroom, aldehydic, fried, chicken, fat, tallow 2 |

| 45 | Nonanoic acid | 1271 | 1269 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | green, fat 1; waxy, dirty, cheesy, dairy 2 | |

| 46 | (3Z)-Hexenyl valerate * | 1282 | 1281 | tr | green, fruity, apple, pear, kiwi, banana, unripe banana, tropical 2 | |

| 47 | Bornyl acetate | 1285 | 1283 | 0.55 ± 0.01 | woody, camphoreous, mentholic, cedar, woody, spicy 2 | |

| 48 | Dihydroedulan II | 1288 | 1284 | 0.26 ± 0.01 | ||

| 49 | Dihydroedulan I | 1293 | 1292 | 0.41 ± 0.00 | ||

| 50 | (2E,4E)-Decadienal | 1316 | 1316 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | fried, wax, fat 1; oily, cucumber, melon, citrus, pumpkin, nutty 2 | |

| 51 | δ-Elemene * | 1339 | 1338 | 0.77 ± 0.00 | 0.44 ± 0.03 | wood 1; sweet, herbal, lavender, woody 2 |

| 52 | α-Cubebene | 1351 | 1351 | tr | citrus, fruit 1; herbal, waxy 2 | |

| 53 | Cyclosativene * | 1368 | 1371 | tr | 0.09 ± 0.01 | |

| 54 | α-Copaene | 1377 | 1376 | 0.44 ± 0.01 | wood, spice 1; woody, spicy, honey 2 | |

| 55 | (E)-Myrtanol acetate * | 1385 | 1386 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | ||

| 56 | β-Bourbonene | 1385 | 1388 | 0.50 ± 0.00 | herb 1; herbal, woody, floral, balsamic 2 | |

| 57 | β-Cubebene | 1388 | 1388 | 0.12 ± 0.00 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | citrus, fruit 1; herbal, waxy, citrus fruity radish 2 |

| 58 | β-Elemene | 1393 | 1390 | 3.71 ± 0.03 | 0.65 ± 0.01 | herb, wax, fresh 1; herbal, waxy fresh 2 |

| 59 | α-Funebrene * | 1401 | 1402 | tr | ||

| 60 | dihydro-α-Ionone * | 1404 | 1406 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | woody, floral, berry, orris, powdery, violet, raspberry, fruity 2 | |

| 61 | α-Barbatene * | 1408 | 1407 | 1.42 ± 0.00 | ||

| 62 | α-Cedrene * | 1413 | 1411 | tr | 0.24 ± 0.00 | woody, cedar, sweet, fresh 2 |

| 63 | α-Santalene * | 1415 | 1417 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | woody 2 | |

| 64 | (E)-Caryophyllene | 1420 | 1419 | 5.29 ± 0.02 | 4.51 ± 0.03 | wood, spice 1; sweet, woody, spicy, clove, dry 2 |

| 65 | (Z)-Thujopsene * | 1430 | 1431 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | ||

| 66 | β-Gurjunene | 1431 | 1432 | 0.33 ± 0.00 | 0.58 ± 0.01 | |

| 67 | β-Copaene | 1432 | 1433 | tr | 0.06 ± 0.00 | wood, spice 1 |

| 68 | γ-Elemene | 1437 | 1436 | 0.18 ± 0.00 | 1.06 ± 0.03 | green, wood, oil 1, 2 |

| 69 | Aromadendrene * | 1440 | 1441 | tr | wood 1 | |

| 70 | β-Barbatene * | 1442 | 1442 | 4.26 ± 0.04 | ||

| 71 | (Z)-β-Farnesene | 1445 | 1442 | 0.15 ± 0.00 | tr | citrus, green 1, 2 |

| 72 | (E)-Muurola-3,5-diene * | 1449 | 1453 | 0.15 ± 0.00 | ||

| 73 | α-Humulene | 1454 | 1454 | 1.34 ± 0.00 | 0.38 ± 0.01 | wood 1, 2 |

| 74 | (E)-β-Farnesene | 1460 | 1456 | 4.83 ± 0.01 | 2.32 ± 0.03 | wood, citrus, sweet 1; woody, citrus, herbal, sweet 2 |

| 75 | Sesquisabinene * | 1464 | 1459 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | ||

| 76 | 9-epi-(E)-Caryophyllene * | 1467 | 1466 | tr | ||

| 77 | β-Acoradiene * | 1468 | 1470 | 3.77 ± 0.06 | ||

| 78 | γ-Gurjunene * | 1475 | 1477 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | musty 2 | |

| 79 | β-Chamigrene * | 1477 | 1477 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | ||

| 80 | γ-Muurolene | 1479 | 1479 | 0.43 ± 0.01 | herb, wood, spice 1; herbal, woody, spicy 2 | |

| 81 | Germacrene D | 1483 | 1481 | 17.53 ± 0.13 | 1.80 ± 0.01 | wood, spice 1; woody, spicy 2 |

| 82 | α-Curcumene | 1483 | 1482 | 0.38 ± 0.01 | herb 1; herbal 2 | |

| 83 | (E)-β-Ionone | 1487 | 1488 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | seaweed, violet, flower, raspberry 1; sweet, fruity, woody, berry, floral, seedy 2 | |

| 84 | β-Selinene * | 1492 | 1490 | 0.38 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.00 | herb 1; herbal 2 |

| 85 | (E)-α-Bergamotene | 1496 | 1494 D | 11.75 ± 0.02 | wood, warm, tea 1, 2 | |

| 86 | Bicyclogermacrene | 1497 | 1500 | 3.33 ± 0.01 | green, wood 1; green, woody, weedy 2 | |

| 87 | α-Muurolene | 1500 | 1500 | 0.21 ± 0.00 | 0.41 ± 0.00 | wood 1 |

| 88 | α-Chamigrene * | 1502 | 1503 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | ||

| 89 | Cuparene * | 1505 | 1504 | 0.89 ± 0.01 | ||

| 90 | Germacrene A | 1505 | 1505 | 0.60 ± 0.00 | ||

| 91 | β-Bisabolene | 1509 | 1505 | 1.66 ± 0.05 | balsamic 1; balsamic, woody 2 | |

| 92 | (E,E)-α-Farnesene | 1510 | 1505 | 7.23 ± 0.03 | 1.01 ± 0.01 | wood, sweet 1; woody, green, vegetable, floral, herbal, citrus 2 |

| 93 | γ-Cadinene | 1515 | 1513 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | wood 1; herbal, woody 2 | |

| 94 | δ-Cadinene | 1517 | 1519 | 0.70 ± 0.02 | thyme, medicine, wood 1; thyme, herbal, woody, dry 2 | |

| 95 | β-Bazzanene * | 1520 | 1520 | tr | 4.10 ± 0.32 | |

| 96 | Myristicin * | 1522 | 1520 | 0.61 ± 0.01 | spice, warm, balsamic 1; spicy, warm, balsamic, woody 2 | |

| 97 | (E)-Calamenene * | 1522 | 1522 | tr | herb, spice 1, 2 | |

| 98 | β-Sesquiphellandrene | 1525 | 1522 | 1.51 ± 0.01 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | wood 1; herbal, fruity, woody 2 |

| 99 | (Z)-Nerolidol * | 1534 | 1532 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.68 ± 0.02 | wax 1; waxy, floral 2 |

| 100 | α-Cadinene * | 1539 | 1538 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | woody, dry 2 | |

| 101 | (E)-α-Bisabolene * | 1545 | 1544 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | balsamic, spicy, floral 2 | |

| 102 | α-Calacorene | 1555 | 1545 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | woody 2 | |

| 103 | Germacrene B | 1558 | 1561 | 0.68 ± 0.01 | 4.59±0.03 | wood, earth, spice 1; woody, earthy, spicy 2 |

| 104 | (E)-Nerolidol | 1565 | 1563 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | wood, flower, wax 1; floral, green, citrus, woody, waxy 2 | |

| 105 | (-)-Spathulenol * | 1576 | 1578 | 0.58 ± 0.00 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | honey 2 |

| 106 | Spathulenol | 1578 | 1578 | 1.39 ± 0.01 | 2.94 ± 0.04 | herb, fruit 1; earthy, herbal, fruity 2 |

| 107 | Caryophyllene oxide | 1583 | 1583 | 1.74 ± 0.02 | 1.35 ± 0.02 | herb, sweet, spice 1; sweet, fresh, dry, woody, spicy 2 |

| 108 | allo-Hedycaryol * | 1587 | 1589 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.19 ± 0.00 | |

| 109 | Salvial-4(14)-en-1-one | 1590 | 1594 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | |

| 110 | Cedrol * | 1599 | 1596 | 0.30 ± 0.01 | cedarwood, woody, dry, sweet 2 | |

| 111 | Widdrol | 1602 | 1599 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | ||

| 112 | Santalol * | 1606 | 1617 | 0.50 ± 0.03 | sweet, sandalwood, woody 2 | |

| 113 | Humulene epoxide II | 1609 | 1608 | 0.28 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | herbal 2 |

| 114 | β-Atlantol * | 1612 | 1608 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | ||

| 115 | γ-Eudesmol * | 1630 | 1632 | 0.92 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | waxy, sweet 2 |

| 116 | epi-α-Cadinol | 1639 | 1640 | 0.43 ± 0.02 | 0.49 ± 0.00 | |

| 117 | t-Muurolol | 1647 | 1642 | 0.42 ± 0.00 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | herbal, spicy, honey 2 |

| 118 | α-Muurolol * | 1643 | 1646 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | balsamic, earthy 2 | |

| 119 | β-Eudesmol | 1651 | 1650 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | herbal, honey 2 | |

| 120 | α-Cadinol | 1655 | 1654 | 1.70 ± 0.01 | 0.42 ± 0.01 | herb, wood 1 |

| 121 | neo-Intermedeol * | 1661 | 1660 | 0.42 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | |

| 122 | 14-hydroxy-(Z)-Caryophyllene * | 1670 | 1667 | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | |

| 123 | (Z)-α-Santalol * | 1673 | 1675 | 0.56 ± 0.00 | 0.52 ± 0.10 | woody, sandalwood 2 |

| 124 | Apiole * | 1680 | 1678 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | woody, spicy 2 | |

| 125 | Elemol acetate * | 1683 | 1680 | 0.13 ± 0.00 | 0.31 ± 0.09 | |

| 126 | α-Bisabolol * | 1686 | 1685 | 0.64 ± 0.16 | floral, peppery, balsamic, clean 2 | |

| 127 | Germacra-4(15),5,10(14)-trien-1-α-ol * | 1686 | 1686 | 0.21 ± 0.00 | ||

| 128 | (Z)-α-trans-Bergamotol * | 1689 | 1690 | 1.09 ± 0.08 | ||

| 129 | Eudesm-7(11)-en-4-ol | 1708 | 1700 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | ||

| 130 | 14-hydroxy-α-Humulene * | 1713 | 1714 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | |

| 131 | (E)-Nerolidyl acetate * | 1717 | 1717 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | fresh, sweet, citrus, waxy, freesia, woody 2 | |

| 132 | (2E,6E)-Farnesol | 1737 | 1743 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | muguet 1; muguet, floral, sweet, lily, waxy 2 | |

| 133 | β-Acoradienol * | 1765 | 1763 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | |

| 134 | Hexahydrofarnesyl acetone | 1846 | 1847 | 0.07 ± 0.00 | oily, herbal, jasmine, celery, woody 2 | |

| 135 | Pentadecanoic acid * | 1862 | 1862 | tr | 0.17 ± 0.01 | waxy 2 |

| 136 | Isophytol * | 1948 | 1947 | 4.06 ± 0.01 | floral, herbal, green 2 | |

| 137 | n-Hexadecanoic acid | 1963 | 1960 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 4.89 ± 0.06 | waxy, fatty 2 |

| 138 | (Z)-Falcarinol | 2035 | 2036 | 0.57 ± 0.01 | 4.60 ± 0.01 | |

| 139 | (E)-Phytol | 2113 | 2122 | 1.15 ± 0.06 | flower1; floral, balsamic, powdery, waxy 2 | |

| 140 | Linoleic acid * | 2132 | 2133 | 1.37 ± 0.11 | faint fatty 2 | |

| 141 | α-Linolenic acid * | 2139 | 2143 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | faint fatty 2 | |

| 142 | (E)-Phytol acetate * | 2219 | 2218 | tr | 0.08 ± 0.01 | waxy, floral, fruity, green, orchid, oily, balsamic 2 |

| 143 | n-Pentacosane | 2500 | 2500 | tr | ||

| 144 | Heptacosane * | 2700 | 2700 | tr | ||

| Total identified, % | 117/99.39 | 88/99.24 |

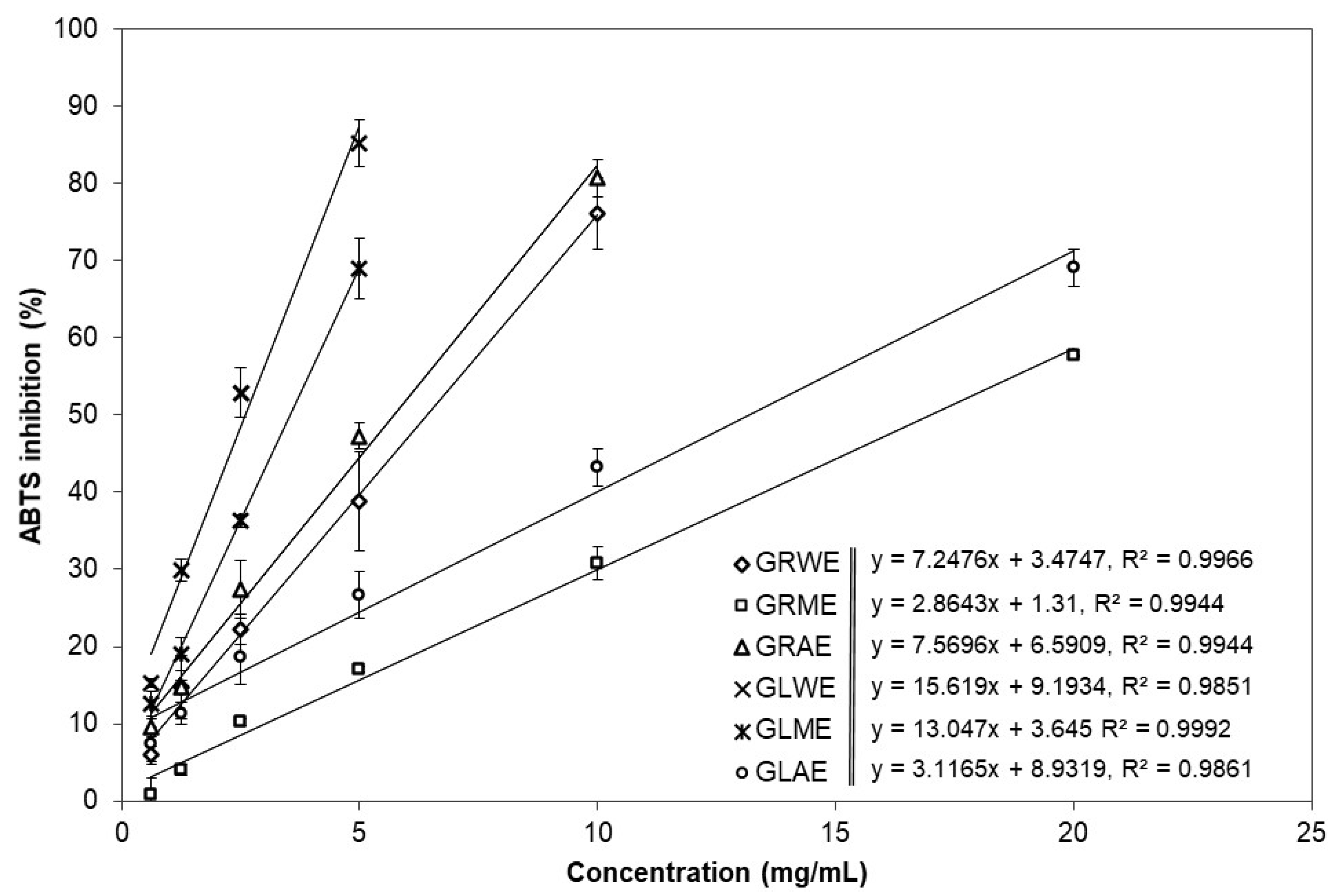

2.2. Antioxidant Potential of A. podagraria Extracts

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Material

3.2. Chemicals and Solvents

3.3. Isolation of Essential Oils (EOs) and Preparation of Goutweed Extracts

3.4. Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

3.5. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

3.6. DPPH• Scavenging Capacity

3.7. ABTS•+ Scavenging Capacity

3.8. Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity

3.9. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jakubczyk, K.; Łukomska, A.; Czaplicki, S.; Wajs-Bonikowska, A.; Gutowska, I.; Czapla, N.; Tańska, M.; Janda-Milczarek, K. Bioactive Compounds in Aegopodium podagraria Leaf Extracts and Their Effects against Fluoride-Modulated Oxidative Stress in the THP-1 Cell Line. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orav, A.; Viitak, A.; Vaher, M. Identification of bioactive compounds in the leaves and stems of Aegopodium podagraria by various analytical techniques. Procedia Chem. 2010, 2, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.; Berset, C.; Kessler, M.; Hamburger, M. Medicinal herbs for the treatment of rheumatic disorders—A survey of European herbals from the 16th and 17th century. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 121, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dębia, K.; Dzięcioł, M.; Wroblewska, A.; Janda-Milczarek, K. Goutweed (Aegopodium podagraria L.)—An Edible Weed with Health-Promoting Properties. Molecules 2025, 30, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyro, O.O.; Tovchiga, O.V.; Stepanova, S.I.; Shtrygol, S.Y. Study of the composition of the goutweed flowers essential oil, its renal effects and influence on uric acid exchange. Phcog. Commn. 2012, 2, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olas, B.; Różański, W.; Urbańska, K.; Sławińska, N.; Bryś, M. Review. New Light on Plants and Their Chemical Compounds Used in Polish Folk Medicine to Treat Urinary Diseases. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarıaltın, S.Y.; Polat, D.Ç.; Yalçın, C.Ö. Cytotoxic and antioxidant activities and phytochemical analysis of Smilax excelsa L. and Aegopodium podagraria L. Food Biosci. 2023, 52, 102359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzei, R.; Leonti, M.; Spadafora, S.; Patitucci, A.; Tagarelli, G. A review of the antimicrobial potential of herbal drugs used in popular Italian medicine (1850s–1950s) to treat bacterial skin diseases. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 250, 112443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurkova, N.; Protsenko, M.; Lobanova, I.; Filippova, E.; Vysochina, G. Antiviral activity of Siberian wild and cultivated plants. BIO Web Conf. 2020, 24, 00051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanovic, O.; Comic, L.; Stanojevic, D.; Solujic-Sukdolak, S. Antibacterial Activity of Aegopodium podagraria L. Extracts and Interaction Between Extracts and Antibiotics. Turk. J. Biol. 2009, 33, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.P.; Brandt, K. Bioactive Polyacetylenes in Food Plants of the Apiaceae Family: Occurrence, Bioactivity and Analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2006, 41, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nizioł-Łukaszewska, Z.; Zagórska-Dziok, M.; Ziemlewska, A.; Bujak, T. Comparison of the Antiaging and Protective Properties of Plants from the Apiaceae Family. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 5307614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prior, R.M.; Lundgaard, N.H.; Light, M.E.; Stafford, G.I.; van Staden, J.; Jäger, A.K. The polyacetylene falcarindiol with COX-1 activity isolated from Aegopodium podagraria L. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 113, 176–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubczyk, K.; Janda, K.; Styburski, D.; Lukomska, A. Goutweed (Aegopodium podagraria L.)—Botanical characteristics and prohealthy properties. Postępy Hig. Med. Dośw. 2020, 74, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leurentop, L.; Verbelen, J.P.; Peumans, W.J. Electron-microscopic analysis of ground elder (Aegopodium podagraria L.) lectin: Evidence for a new type of supra-molecular protein structure. Planta 1987, 172, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapetanos, C.; Karioti, A.; Bojović, S.; Marin, P.; Veljić, M.; Skaltsa, H. Chemical and principal-component analyses of the essential oils of Apioideae taxa (Apiaceae) from Central Balkan. Chem. Biodivers. 2008, 5, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramonov, E.A.; Khalilova, A.Z.; Odinokov, V.N.; Khalilov, L.M. Identification and biological activity of volatile organic compounds isolated from plants and insects. III. Chromatography-mass spectrometry of volatile compounds of Aegopodium podagraria. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2000, 36, 584–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.V.; Sree, N.R.S.; Ranjit, P.; Maddela, N.R.; Kumar, V.; Jha, P.; Prasad, R.; Radice, M. Essential oils, herbal extracts and propolis for alleviating Helicobacter pylori infections: A critical view. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 157, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, G.R.; Hariharan, G.; Amalraj, S.; Hillary, V.E.; Araujo, H.C.S.; Montalvao, M.M.; Borges, L.P.; Gurgel, R.Q. Neuropharmacological mechanisms and psychotherapeutic effects of essential oils: A systematic review. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2025, 181, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šircelj, H.; Petkovsek, M.M.; Veberič, R.; Hudina, M.; Slatnar, A. Lipophilic antioxidants in edible weeds from agricultural areas. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2018, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranauskienė, R.; Venskutonis, P.R.; Ragažinskienė, O. Valorisation of Roman chamomile (Chamaemelum nobile L.) herb by comprehensive evaluation of hydrodistilled aroma and residual non-volatile fractions. Food Res. Int. 2022, 160, 111715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aqeel, U.; Aftab, T.; Khan, M.M.A.; Naeem, M. Regulation of essential oil in aromatic plants under changing environment. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2023, 32, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Wang, C. Polyacetylenes in herbal medicine: A comprehensive review of its occurrence, pharmacology, toxicology, and pharmacokinetics (2014–2021). Phytochemistry 2022, 201, 113288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warsito, M.F. A Review on Chemical Composition, Bioactivity, and Toxicity of Myristica fragrans Houtt. Essential Oil. Indones. J. Pharm. 2021, 32, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.P. Identification of Essential Oils Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry, 4th ed.; Allured Business Media: Carol Stream, IL, USA, 2017; p. 803. [Google Scholar]

- Borg-Karlson, A.-N.; Valterová, I.; Nilsson, L.A. Volatile compounds from flowers of six species in the family Apiaceae: Bouquets for different pollinators? Phytochemistry 1994, 35, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewska, A.; Janda, K.; Makuch, E.; Walasek, M.; Miądlicki, P.; Jakubczyk, K. Effect of extraction method on the antioxidative activity of ground elder (Aegopodium podagraria L.). Pol. J. Chem. Technol. 2019, 21, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flieger, J.; Flieger, M. The [DPPH●/DPPH-H]-HPLC-DAD Method on Tracking the Antioxidant Activity of Pure Antioxidants and Goutweed (Aegopodium podagraria L.) Hydroalcoholic Extracts. Molecules 2020, 25, 6005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Ou, B.; Prior, R.L. The chemistry behind antioxidant capacity assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valyova, M.; Tashev, A.N.; Stoyanov, S.; Yordanova, S.; Ganeva, Y. In vitro free-radical scavenging activity of Aegopodium podagraria L. and Orlaya grandiflora (L.) Hoffm. (Apiaceae). J. Chem. Technol. Metall. 2016, 51, 271–274. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.; Ou, B.; Hampsch-Woodill, M.; Flanagan, J.A.; Prior, R.L. High-throughput assay of oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) using a multichannel liquid handling system coupled with a microplate fluorescence reader in 96-well format. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 4437–4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryževičiūtė, N.; Kraujalis, P.; Venskutonis, P.R. Optimization of high pressure extraction processes for the separation of raspberry pomace into lipophilic and hydrophilic fractions. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2016, 108, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Extract | Yield (%) | TPC mg GAE/g edw | DPPH EC50 (mg/mL) | DPPH µM TE/g edw | ABTS EC50 (mg/mL) | ABTS µM TE/g edw | ORAC µM TE/g edw |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRWE | 26.47 ± 0.60 c | 20.37 ± 0.15 c | 10.36 ± 0.49 c | 43.46 ± 2.11 d | 6.44 ± 0.20 b | 177.38 ± 5.53 c | 700.49 ± 62.74 b |

| GRME | 29.54 ± 1.45 d | 12.88 ± 0.24 a | 27.41 ± 1.04 f * | 16.42 ± 0.61 b | 8.69 ± 0.35 d | 131.47 ± 5.19 b | 484.21 ± 78.00 a |

| GRAE | 3.53 ± 0.23 b | 25.30 ± 0.28 d | 16.78 ± 0.07 e | 26.79 ± 0.12 c | 5.73 ± 0.12 b | 199.01 ± 4.20 c | 1222.18 ± 53.75 c |

| GLWE | 37.02 ± 0.83 e | 62.12 ± 1.10 g | 1.18 ± 0.01 a | 382.16 ± 4.19 f | 2.45 ± 0.14 a | 467.64 ± 26.29 e | 1425.59 ± 56.42 c |

| GLME | 25.25 ± 1.45 c | 56.84 ± 1.05 f | 2.48 ± 0.11 b | 181.57 ± 7.65 e | 3.57 ± 0.25 a | 320.33 ± 22.04 d | 1293.06 ± 118.70 c |

| GLAE | 4.70 ± 0.30 b | 51.49 ± 0.84 e | 11.93 ± 0.31 d | 37.71 ± 0.97 d | 13.20 ± 0.62 c | 86.60 ± 4.24 a | 1285.91 ± 61.39 c |

| GLEO | 0.22 ± 0.01 a | 16.52 ± 0.23 b | – | 2.97 ± 0.69 a | – | 171.93 ± 5.95 c | – |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baranauskienė, R.; Račkauskienė, I.; Venskutonis, P.R. Characterization of Steam Volatiles and Evaluation of the Antioxidant Properties of Different Extracts from Leaves and Roots of Aegopodium podagraria L. Molecules 2025, 30, 4786. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244786

Baranauskienė R, Račkauskienė I, Venskutonis PR. Characterization of Steam Volatiles and Evaluation of the Antioxidant Properties of Different Extracts from Leaves and Roots of Aegopodium podagraria L. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4786. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244786

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaranauskienė, Renata, Ieva Račkauskienė, and Petras Rimantas Venskutonis. 2025. "Characterization of Steam Volatiles and Evaluation of the Antioxidant Properties of Different Extracts from Leaves and Roots of Aegopodium podagraria L." Molecules 30, no. 24: 4786. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244786

APA StyleBaranauskienė, R., Račkauskienė, I., & Venskutonis, P. R. (2025). Characterization of Steam Volatiles and Evaluation of the Antioxidant Properties of Different Extracts from Leaves and Roots of Aegopodium podagraria L. Molecules, 30(24), 4786. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244786