Phlorotannins from Phaeophyceae: Structural Diversity, Multi-Target Bioactivity, Pharmacokinetic Barriers, and Nanodelivery System Innovation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Elucidating ecological origins and biosynthetic regulation affecting raw material standardization;

- (2)

- Characterizing chemical architecture and structure–activity relationships;

- (3)

- Reviewing extraction, purification, and analytical methodologies emphasizing green technologies;

- (4)

- Analyzing multi-target bioactive mechanisms including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, anticancer, neuroprotective, and antimicrobial activities;

- (5)

- Examining the bioavailability paradox including physicochemical properties, gastrointestinal modifications, and safety considerations;

- (6)

- Evaluating advanced delivery systems including polymeric nanoparticles, liposomal systems, electrospun nanofibers, and pH-responsive platforms;

- (7)

- Addressing industrial translation challenges including controlled aquaculture, heavy metal contamination, purification economics, and regulatory pathways.

2. Ecological Role and Chemical Structure of Phlorotannins

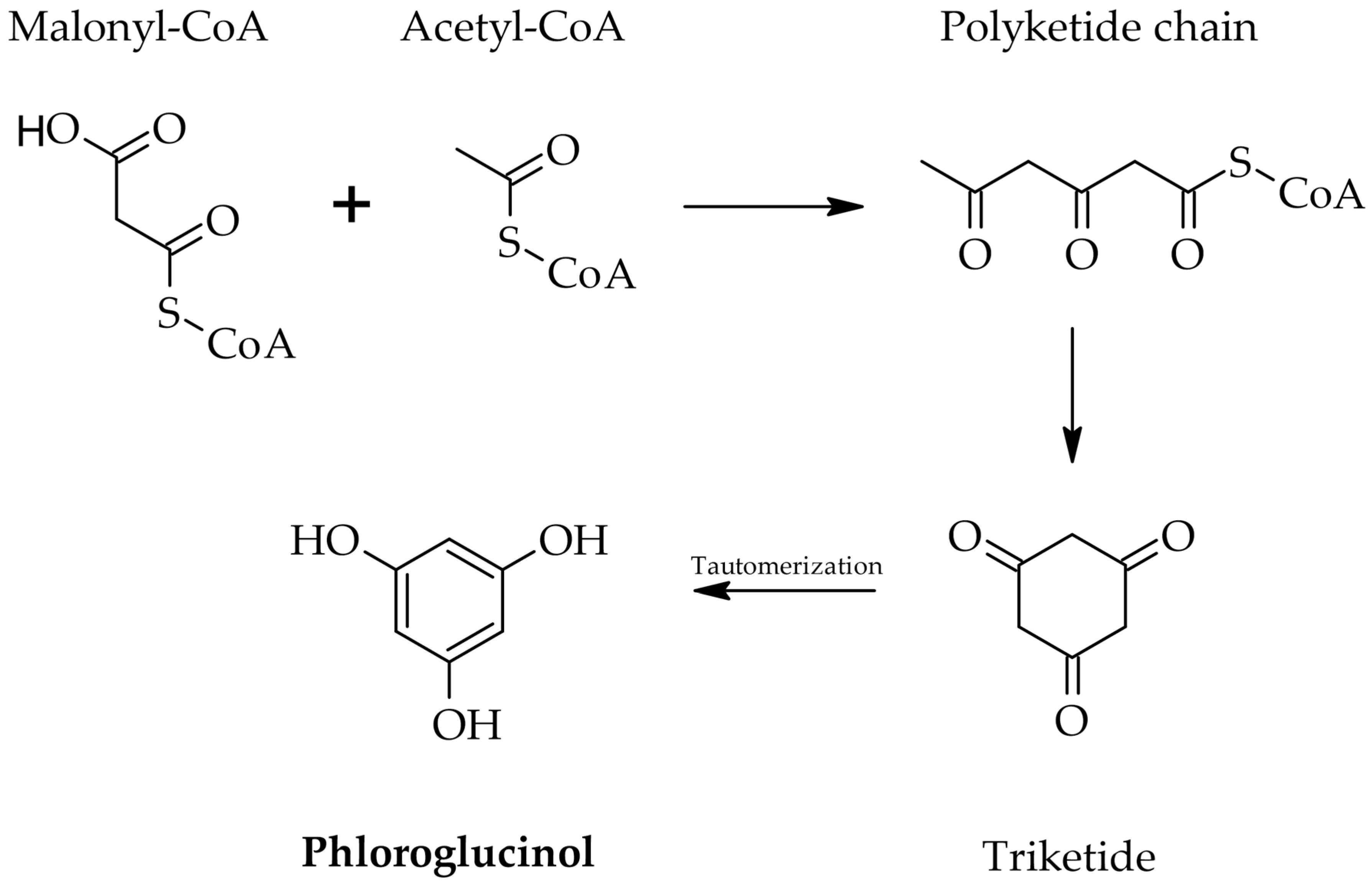

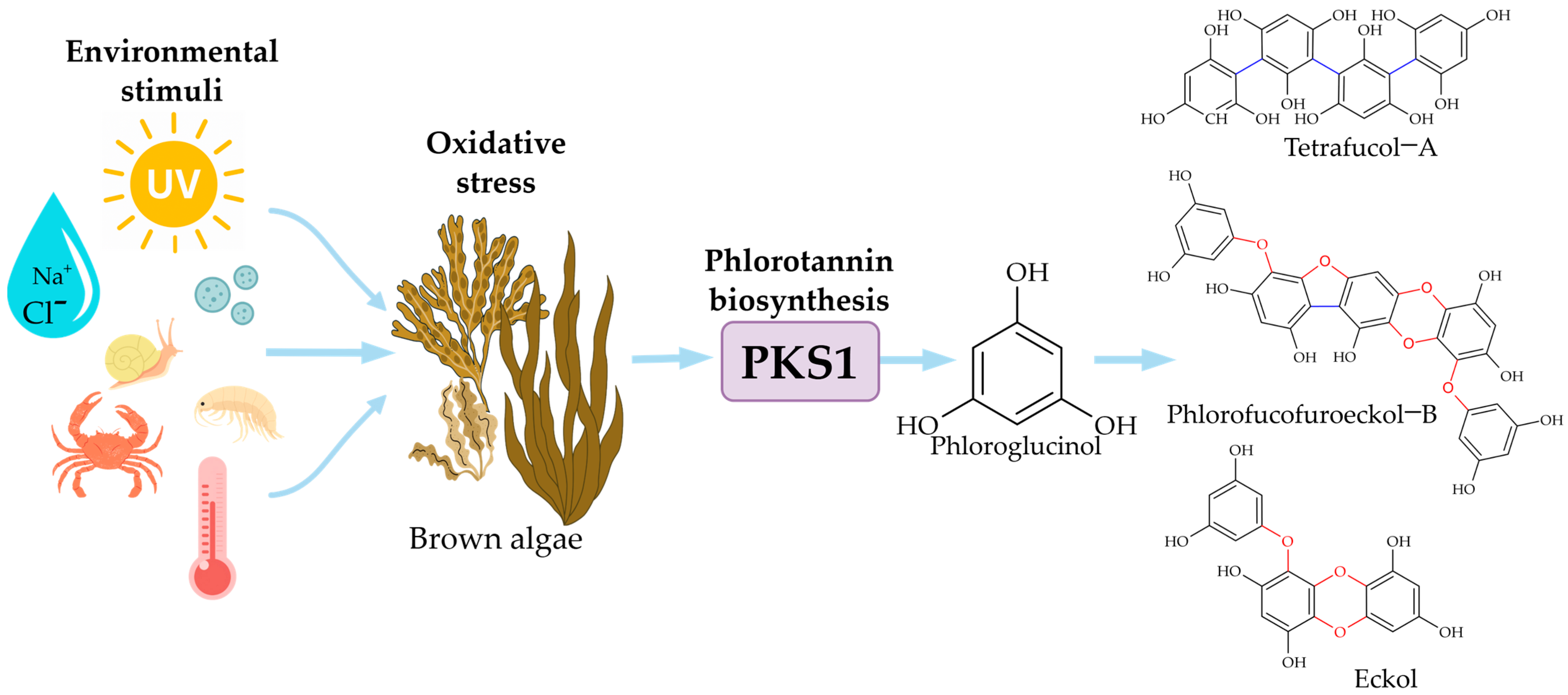

2.1. Ecological Role and Biosynthetic Regulation

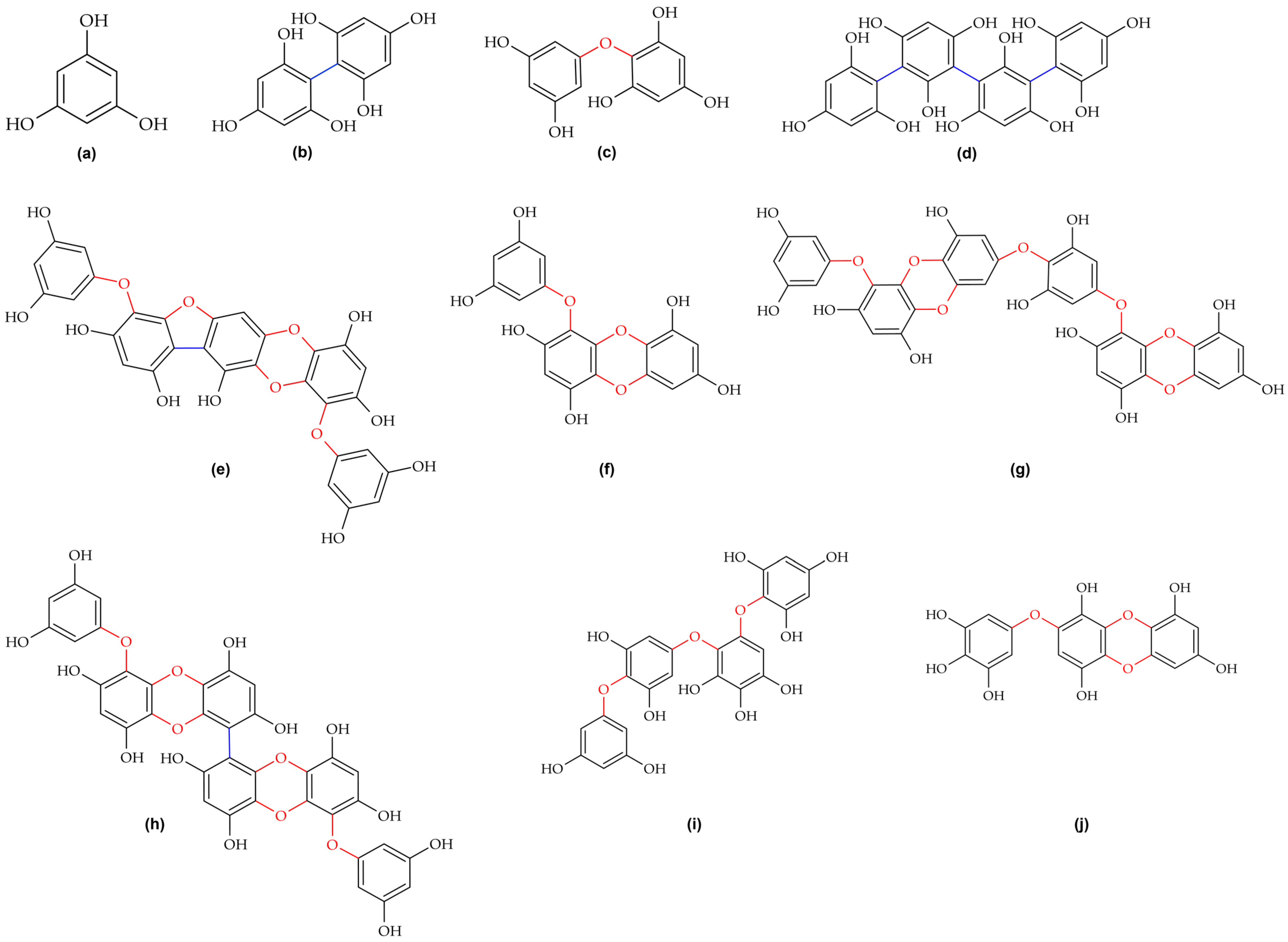

2.2. Structural Diversity and Classification

3. Extraction, Purification, and Analytical Characterization

Structural Identification and Quantification

4. The Bioavailability Problem and Pharmacokinetic Barriers

5. Advanced Delivery Systems and Formulation Innovations

5.1. Rationale and Design Principles

5.2. Polymeric Nanoparticle Systems

5.3. Liposomal and Vesicular Delivery Systems

5.4. Electrospun Nanofibers

5.5. pH-Responsive and Targeted Release Systems

5.6. Emerging Technologies

6. From Laboratory to Industry: Standardization and Scale-Up Challenges

6.1. Raw Material Inconsistency and Standardization Crisis

6.2. Heavy Metal Contamination

6.3. Controlled Cultivation Environments

6.4. Purification Economics

6.5. Industrial Applications and Market Status

6.6. Quality Control and Analytical Standardization

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khan, F.; Jeong, G.-J.; Khan, M.S.A.; Tabassum, N.; Kim, Y.-M. Seaweed-Derived Phlorotannins: A Review of Multiple Biological Roles and Action Mechanisms. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.R.G.; Paul, P.T.; Anas, K.K.; Tejpal, C.S.; Chatterjee, N.S.; Anupama, T.K.; Mathew, S.; Ravishankar, C.N. Phlorotannins-bioactivity and extraction perspectives. J. Appl. Phycol. 2022, 34, 2173–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, L. A bioactive substance derived from brown seaweeds: Phlorotannins. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catarino, M.D.; Pires, S.M.G.; Silva, S.; Costa, F.; Braga, S.S.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Silva, A.M.S.; Cardoso, S.M. Overview of Phlorotannins’ Constituents in Fucales. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, T.; Ito, H. Tannins of constant structure in medicinal and food plants—Hydrolyzable tannins and polyphenols related to tannins. Molecules 2011, 16, 2191–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.J.; Zhang, W.W.; Li, X.M.; Wang, B.G. Evaluation of antioxidant property of extract and fractions obtained from a red alga, Polysiphonia urceolata. Food Chem. 2023, 95, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaza Martínez, J.H.; Torres, H. Preparation and chromatographic analysis of phlorotannins. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2013, 51, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besednova, N.N.; Andryukov, B.G.; Zaporozhets, T.S.; Kryzhanovsky, S.P.; Kuznetsova, T.A.; Fedyanina, L.N.; Makarenkova, I.D.; Zvyagintseva, T.N. Algae polyphenolic compounds and modern antibacterial strategies: Current achievements and immediate prospects. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catarino, M.D.; Silva, A.M.S.; Cardoso, S.M. Phycochemical constituents and biological activities of Fucus spp. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert, M.; Franco, D.; Sineiro, J.; Moreira, R. Antioxidant and antidiabetic properties of phlorotannins from Ascophyllum nodosum seaweed extracts. Molecules 2023, 28, 4937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomartire, S.; Cotas, J.; Pacheco, D.; Marques, J.C.; Pereira, L.; Gonçalves, A.M.M. Environmental impact on seaweed phenolic production and activity: An important step for compound exploitation. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jormalainen, V.; Honkanen, T.; Heikkilä, N. Feeding preferences and performance of a marine isopod on seaweed hosts: Cost of habitat specialization. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2001, 220, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, E.; AbuGhannam, N. Antibacterial derivatives of marine algae: An overview of pharmacological mechanisms and applications. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okeke, E.S.; Nweze, E.J.; Chibuogwu, C.C.; Anaduaka, E.G.; Chukwudozie, K.I.; Ezeorba, T.P.C. Aquatic phlorotannins and human health: Bioavailability, toxicity, and future prospects. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2021, 16, 1934578X211056144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alassali, A.; Cybulska, I. Methods for upstream extraction and chemical characterization of secondary metabolites from algae biomass. Adv. Tech. Biol. Med. 2015, 4, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.A.O.; Félix, R.; Pais, A.C.S.; Rocha, S.M.; Silvestre, A.J.D. The quest for phenolic compounds from macroalgae: A review of extraction and identification methodologies. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, L.; Theodoridou, K.; Sheldrake, G.N.; Walsh, P. A critical review of analytical methods used for the chemical characterisation and quantification of phlorotannin compounds in brown seaweeds. Phytochem. Anal. 2019, 30, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echave, J.; Lourenço-Lopes, C.; Cassani, L.; Fraga-Corral, M.; Garcia-Perez, P.; Otero, P.; Carreira-Casais, A.; Perez-Gregorio, R.; Baamonde, S.; Saa, F.F.; et al. Evidence and perspectives on the use of phlorotannins as novel antibiotics and therapeutic natural molecules. Med. Sci. Forum 2022, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotas, J.; Leandro, A.; Monteiro, P.; Pacheco, D.; Figueirinha, A.; Gonçalves, A.M.M.; da Silva, G.J.; Pereira, L. Seaweed phenolics: From extraction to applications. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arazo-Rusindo, M.; Rivera-Andrades, G.; Simón, L.; Pérez-Jiménez, J.; Sáyago-Ayerdi, S.G.; Pérez-Correa, J.R.; Castillo-Valenzuela, O.; Martínez-Cifuentes, M.; Pérez-Bravo, F.; Mariotti-Celis, M.S. Evaluation of phlorotannin bioaccessibility and antioxidant capacity stability of a safe and sustainable brown seaweed extract: Role of age-related digestion changes and matrix composition. Res. Sq. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, T.; Liu, X.; Yu, C. Extraction and nano-sized delivery systems for phlorotannins to improve their bioavailability and bioactivity. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón, L.; Arazo-Rusindo, M.; Quest, A.F.G.; Mariotti-Celis, M.S. Phlorotannins: Novel Orally Administrated Bioactive Compounds That Induce Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress in Cancer. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meslet-Cladière, L.; Delage, L.; Leroux, C.; Goulitquer, S.; Leblanc, C.; Creis, E.; Ar Gall, E.; Stiger-Pouvreau, V.; Czjzek, M.; Potin, P. Structure/function analysis of a type III polyketide synthase in the brown alga Ectocarpus siliculosus reveals a biochemical pathway in phlorotannin monomer biosynthesis. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 3089–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Zhang, W.; Smid, S.D. Phlorotannins: A review on biosynthesis, chemistry and bioactivity. Food Biosci. 2021, 39, 100832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, G. Seaweeds from the Portuguese Coast: Chemistry, Antimicrobial and Anti-Inflammatory Capacity. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Getachew, A.T.; Jacobsen, C.; Holdt, S.L. Emerging Technologies for the Extraction of Marine Phenolics: Opportunities and Challenges. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Qian, Z.-J.; Kim, M.-M.; Kim, S.-K. Cytotoxic Activities of Phlorethol and Fucophlorethol Derivatives Isolated from Ecklonia cava (Laminariaceae). J. Food Biochem. 2011, 35, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkemeyer, C.; Lemesheva, V.; Billig, S.; Tarakhovskaya, E. Composition of Intracellular and Cell Wall-Bound Phlorotannin Fractions in Fucoid Algae Indicates Specific Functions of These Metabolites Dependent on the Chemical Structure. Metabolites 2020, 10, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manca, A. A simple method for the extraction and purification of phlorotannins from brown algae. In Protocols for Marine Natural Product Research; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarante, S.J.; Catarino, M.D.; Marçal, C.; Silva, A.M.S.; Ferreira, R.; Cardoso, S.M. Microwave-assisted extraction of phlorotannins from Fucus vesiculosus. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, L.; Stratakos, A.C.; Theodoridou, K.; Dick, J.T.A.; Sheldrake, G.N.; Linton, M.; Corcionivoschi, N.; Walsh, P.J. Polyphenols from brown seaweeds as a potential antimicrobial agent in animal feeds. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 3399–3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Chen, L.; Lu, T.; Yao, L.; Jiang, H.; Qiu, H.; Li, C. Investigation of the potential phlorotannins and mechanism of six brown algae in treating type II diabetes mellitus based on biological activity, UPLC-QE-MS/MS, and network pharmacology. Foods 2023, 12, 3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.; Liu, S.; Tian, M.; Huang, S.; Ai, Z.; Gu, X.; Chen, D.; Zhao, Q.; Li, X. Isolation of a neuroprotective phlorotannin from the marine algae Ecklonia maxima by high-speed counter-current chromatography and Sephadex LH-20 chromatography. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugiura, Y.; Matsuda, K.; Yamada, Y.; Nishikawa, M.; Shioya, K.; Katsuzaki, H.; Imai, K.; Amano, H. Isolation of a new anti-allergic phlorotannin, phlorofucofuroeckol-B, from an edible brown alga, Eisenia arborea. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2006, 70, 2807–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.M.; Dang, H.T.; Hwang, C.E.; Ahn, M.J.; Kim, D.K.; Choi, S.Y.; Yoon, N.Y.; Phan, T.T.V.; Kang, M.C.; Yim, M.J. Dereplication by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectroscopy (qTOF-MS) and antiviral activities of phlorotannins from Ecklonia cava. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, M.; Romaní, A.; Santos, J.; Pires, P.; Del-Río, P.; Mata, F.; Fernandes, É.; Ramos, C.; Vaz-Velho, M. High-Value Brown Algae Extracts Using Deep Eutectic Solvents and Microwave-Assisted Extraction. Foods 2025, 14, 2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goya, L.; Mateos, R. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Marine Phlorotannins and Bromophenols Supportive of Their Anticancer Potential. Nutr. Rev. 2025, 83, e1225–e1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-M.; Glombitza, K.-W. Carmalols and Phlorethofuhalols from the Brown Alga Carpophyllum maschalocarpum. Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 3417–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catarino, M.D.; Amarante, S.J.; Mateus, N.; Silva, A.M.S.; Cardoso, S.M. Brown Algae Phlorotannins: A Marine Alternative to Break the Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Cancer Network. Foods 2021, 10, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yotsu-Yamashita, M.; Kondo, S.; Segawa, S.; Lin, Y.C.; Toyohara, H.; Ito, H.; Konoki, K.; Cho, Y.; Uchida, T. Isolation and structural determination of two novel phlorotannins from the brown alga Ecklonia kurome Okamura, and their radical scavenging activities. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, G.; Ji, Y.; Anegboonlap, P.; Hotchkiss, S.; Gill, C.I.R.; Yaqoob, P.; Spencer, J.P.E.; Rowland, I. Gastrointestinal modifications and bioavailability of brown seaweed phlorotannins and effects on inflammatory markers. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 1240–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Sun, Y.; Gu, Y.; Zheng, J.; Yu, C.; Qi, H. Preparation, Characterization and Antioxidant Activities of Kelp Phlorotannin Nanoparticles. Molecules 2020, 25, 4550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallam, I.E.; Abdelwareth, A.; Attia, H.; Aziz, R.K.; Homsi, M.N.; von Bergen, M.; Farag, M.A.; Abdelrahman, E.H. Effect of gut microbiota biotransformation on dietary tannins and human health implications. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.C.; Rosenfeld, C.; Guttendorf, R.; Wade, S.D.; Park, Y.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, B.H.; Hwang, H.J. A pharmacokinetic and bioavailability study of Ecklonia cava phlorotannins following intravenous and oral administration in Sprague-Dawley rats. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIR Expert Panel. Safety Assessment of Brown Algae-Derived Ingredients as Used in Cosmetics; Cosmetic Ingredient Review: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, J.H.; Choi, J.S.; Nam, T.-J. Fucosterol from an Edible Brown Alga Ecklonia stolonifera Prevents Soluble Amyloid Beta-Induced Cognitive Dysfunction in Aging Rats. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, I.P.S.; Sanjeewa, K.K.A.; Samarakoon, K.W.; Lee, W.W.; Kim, H.S.; Kang, N.; Ranasinghe, P.; Lee, H.S.; Jeon, Y.J. A fucoidan fraction purified from Chnoospora minima; a potential inhibitor of LPS-induced inflammatory responses. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 104 Pt A, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allied Market Research. Seaweed Extracts Market Size, Share, Trends|Forecast to 2032. 2023. Available online: https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/seaweed-extracts-market-A12569 (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Transparency Market Research. Seaweed Cosmetic Ingredients Market Size, Share Report 2034. 2024. Available online: https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/seaweed-cosmetic-ingredients-market.html (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Duan, X.; Agar, O.T.; Barrow, C.J.; Dunshea, F.R.; Suleria, H.A.R. Improving Potential Strategies for Biological Activities of Phlorotannins Derived from Seaweeds. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 833–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seanol Science Center. SeaPolynol® and Seanol® Product Information. 2024. Available online: https://seanolinstitute.org/ssc/ (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Safety of Ecklonia cava phlorotannins as a novel food pursuant to Regulation (EC) No 258/97. EFSA J. 2017, 15, e05003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeva Clinical Trials. Phase I Study of PH100 (Ecklonia Cava Phlorotannins). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04141241. 2020. Available online: https://ctv.veeva.com/study/phase-i-study-of-ph100-ecklonia-cava-phlorotannins (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Gager, L.; Connan, S.; Mber, E.G.; Delmail, D.; Triber, F.; Stiger-Pouvreau, V.; Ar Gall, E. Active phlorotannins from seven brown seaweeds commercially harvested in Brittany (France) detected by 1H NMR and in vitro assays: Temporal variation and potential valorization in cosmetic applications. J. Appl. Phycol. 2020, 32, 2375–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horizon Seaweed. Seaweed for Beauty and Cosmetic Applications. 2024. Available online: https://horizonseaweed.com/beauty-cosmetics (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- INCIDecoder. Alaria Esculenta Extract (with Product List). 2024. Available online: https://incidecoder.com/ingredients/alaria-esculenta-extract (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Choi, E.-K.; Park, S.-H.; Ha, K.-C.; Noh, S.-O.; Jung, S.-J.; Chae, H.-J.; Chung, Y.-T.; Chae, S.-W. Clinical trial of the hypolipidemic effects of a brown alga Ecklonia cava extract in patients with hypercholesterolemia. Int. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 11, 798–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Jeon, Y.-J. Efficacy and safety of a dieckol-rich extract (AG-dieckol) of brown algae, Ecklonia cava, in pre-diabetic individuals: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICH GCP Clinical Trials Registry. Ecklonia Cava Phlorotannin in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus with Circulatory Complication (NCT04141241). 2019. Available online: https://ichgcp.net/clinical-trials-registry/NCT04141241 (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Kwon, Y.J.; Kwon, O.I.; Hwang, H.J.; Shin, H.C.; Yang, S. Therapeutic effects of phlorotannins in the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023, 16, 1193590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Phlorotannin Type | Algal Source | Extraction Method | Biological Activities/Applications | Remarks | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fucols | Fucus vesiculosus | Aqueous ethanol, solid–liquid | Prebiotic effect, UV-radiation protection | C–C linked phloroglucinol units; abundant in temperate brown algae | [2] |

| Phlorethols | Ascophyllum nodosum | Ethanol–water + ultrasound | Antioxidant, neuroprotective | Ether linkages; higher solubility than fucols | [3] |

| Fucophlorethol | Sargassum muticum | Deep eutectic solvent (DES) + ultrasound | Antioxidant, enzyme inhibition | Complex mixture; mixed linkages | [36] |

| Eckol | Ecklonia cava (Lessoniaceae/Phaeophyta) | Methanol extraction; SPE purification | Antidiabetic, UV-protection, neuroprotective | Dibenzo-1,4-dioxin ring | [1] |

| Dieckol | Ecklonia cava/E. stolonifera | Enzyme-assisted extraction + SPE | Anti-obesity, anti-photoaging, tyrosinase inhibition | Hexamer phlorotannin | [37] |

| Carmalol | Carpophyllum maschalocarpum | Ethanol extraction | Unstable under gastrointestinal digestion; antioxidant potential | Dibenzodioxin-linkage subclass of phlorotannins | [38] |

| Miscellaneous polymeric phlorotannins | Various Fucaceae, Sargassaceae, Alariaceae | Pressurized liquid extraction (PLE)/MAE/DES | Broad-spectrum antioxidant, UV-shielding | Very high degree of polymerization; structural diversity | [18] |

| Undaria-specific phlorotannins | Undaria pinnatifida (Alariaceae) | Microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) | Skin-whitening, anti-inflammatory (cosmeceutical) | Commercial interest in Asia | [39] |

| Product Name | Algal Source | Key Compounds | Standardization | Regulatory Status | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SeaPolynol™/Seanol® | Ecklonia cava | dieckol, eckol, 6,6′-bieckol, PFF-A | ≥90% total phlorotannins | FDA NDI (2008); EFSA Novel Food (2017) | Dietary supplements, cardiovascular, cognitive |

| Seanol-F | E. cava | eckol derivatives | 13–15% phlorotannins with dextrin | FDA NDI (2008) | Enhanced absorption supplements |

| Ventol® | E. cava | phlorotannin-rich extract | proprietary | Korea FDA approved | Herbal medicine |

| Pepha-Tight® | Nannochloropsis oculata (microalgae) | polysaccharides, phenolics | film-forming matrix | CIR-approved cosmetic | Anti-aging skincare |

| Fucus/Ascophyllum extracts | F. vesiculosus, A. nodosum | fucols, phlorethols | variable (1–15% phenolics) | CosIng listed; GRAS | Cosmetics, agriculture |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harasym, J.; Słota, P.; Pejcz, E. Phlorotannins from Phaeophyceae: Structural Diversity, Multi-Target Bioactivity, Pharmacokinetic Barriers, and Nanodelivery System Innovation. Molecules 2025, 30, 4733. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244733

Harasym J, Słota P, Pejcz E. Phlorotannins from Phaeophyceae: Structural Diversity, Multi-Target Bioactivity, Pharmacokinetic Barriers, and Nanodelivery System Innovation. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4733. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244733

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarasym, Joanna, Patryk Słota, and Ewa Pejcz. 2025. "Phlorotannins from Phaeophyceae: Structural Diversity, Multi-Target Bioactivity, Pharmacokinetic Barriers, and Nanodelivery System Innovation" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4733. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244733

APA StyleHarasym, J., Słota, P., & Pejcz, E. (2025). Phlorotannins from Phaeophyceae: Structural Diversity, Multi-Target Bioactivity, Pharmacokinetic Barriers, and Nanodelivery System Innovation. Molecules, 30(24), 4733. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244733