Multi-Techniques Analysis of Archaeological Pottery—Potential Pitfalls in Interpreting the Results

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

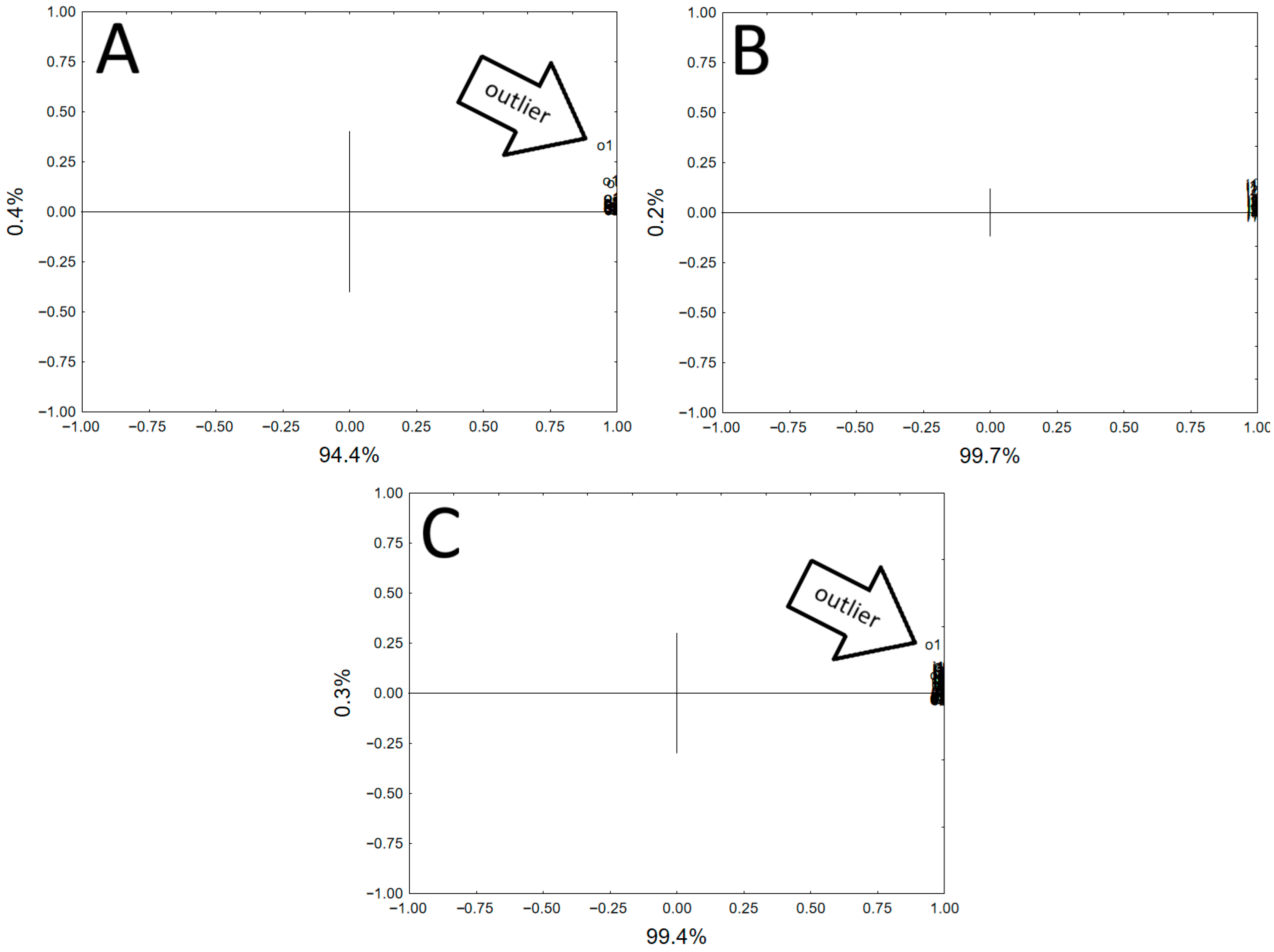

2.1. Non-Destructive XRF Analysis of Whole Vessels

- Different clays were used (or a combination of coarse clays—that is, a matrix from various outcrops).

- The type of admixture was important (medium-fine-grained here).

- The firing temperature may be important—vessel 2 had a different color and turned gray, so either a reduction or a pseudo-reduction firing, and there was certainly oxygen available.

- A combination of the above factors.

2.2. Non-Destructive XRF Analysis of Pottery Fragment

2.3. Destructive Analysis of Pottery Fragments

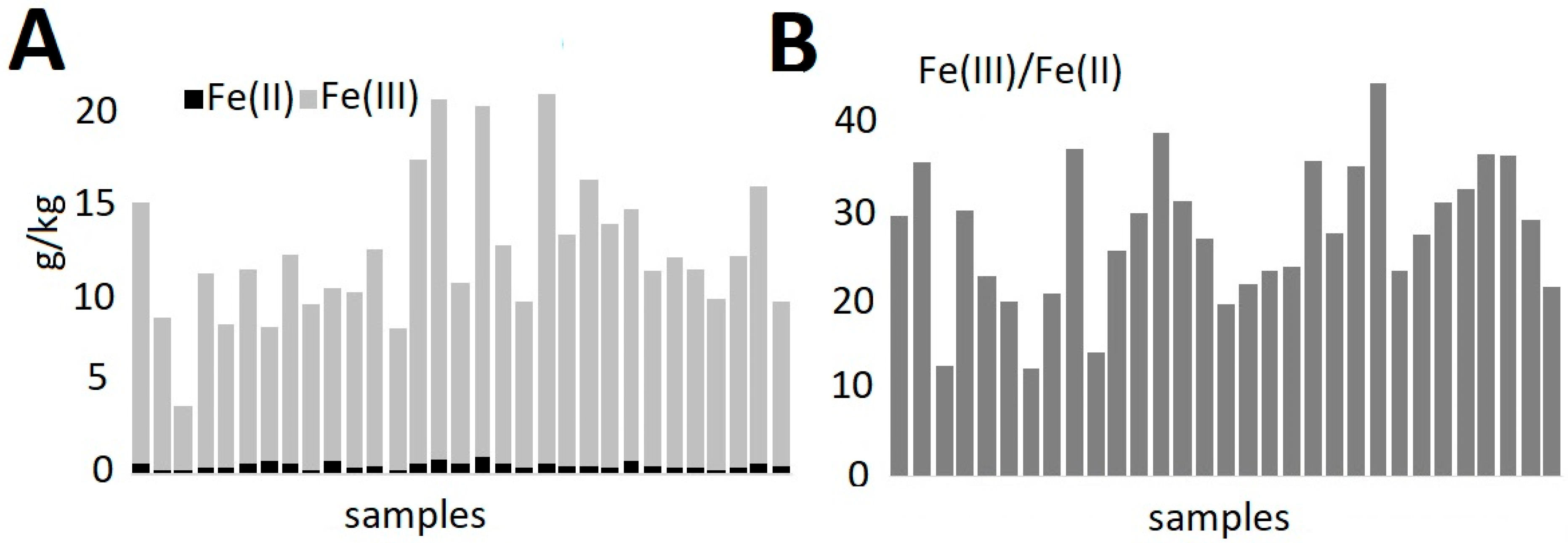

2.3.1. Iron Forms in Pottery

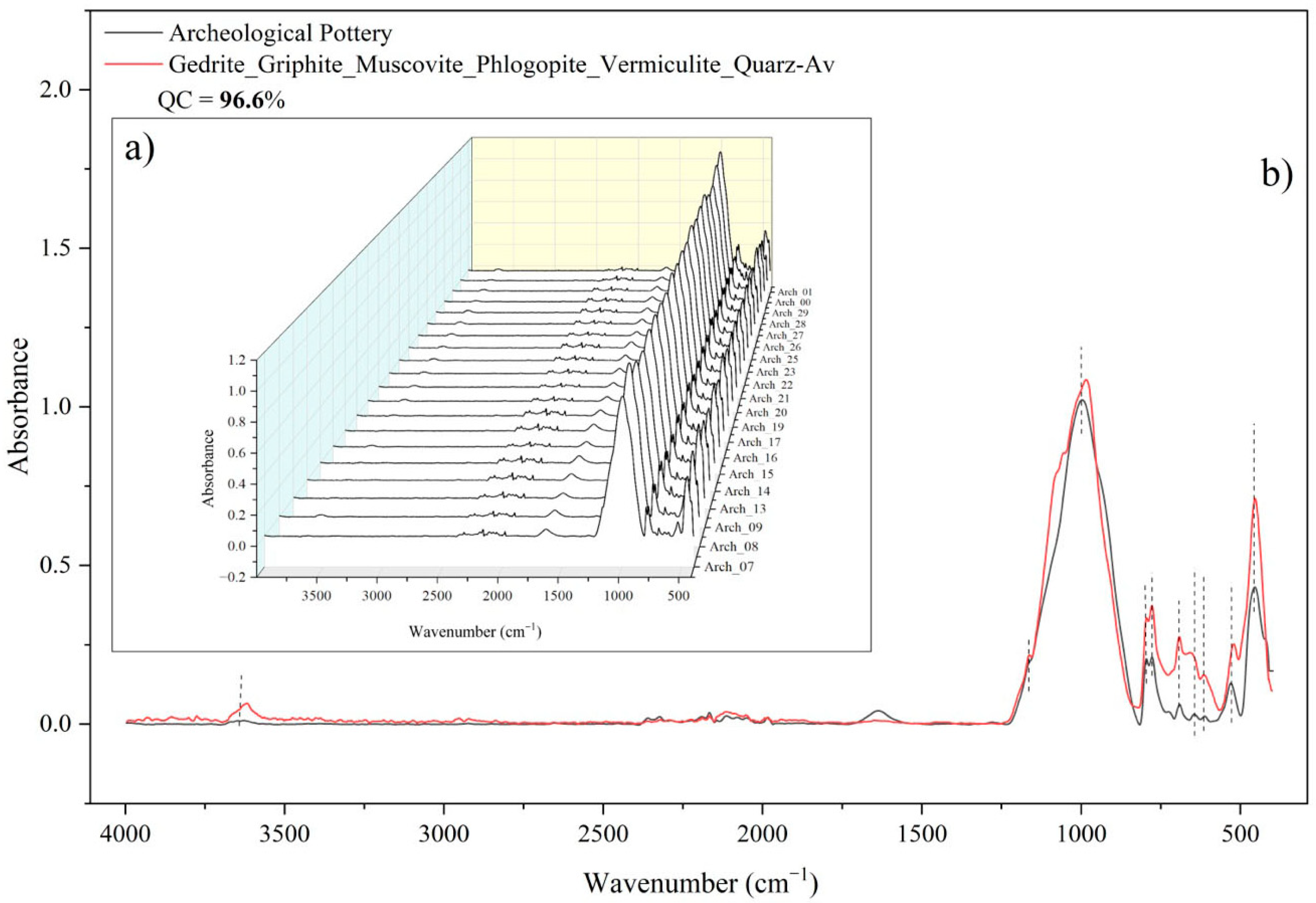

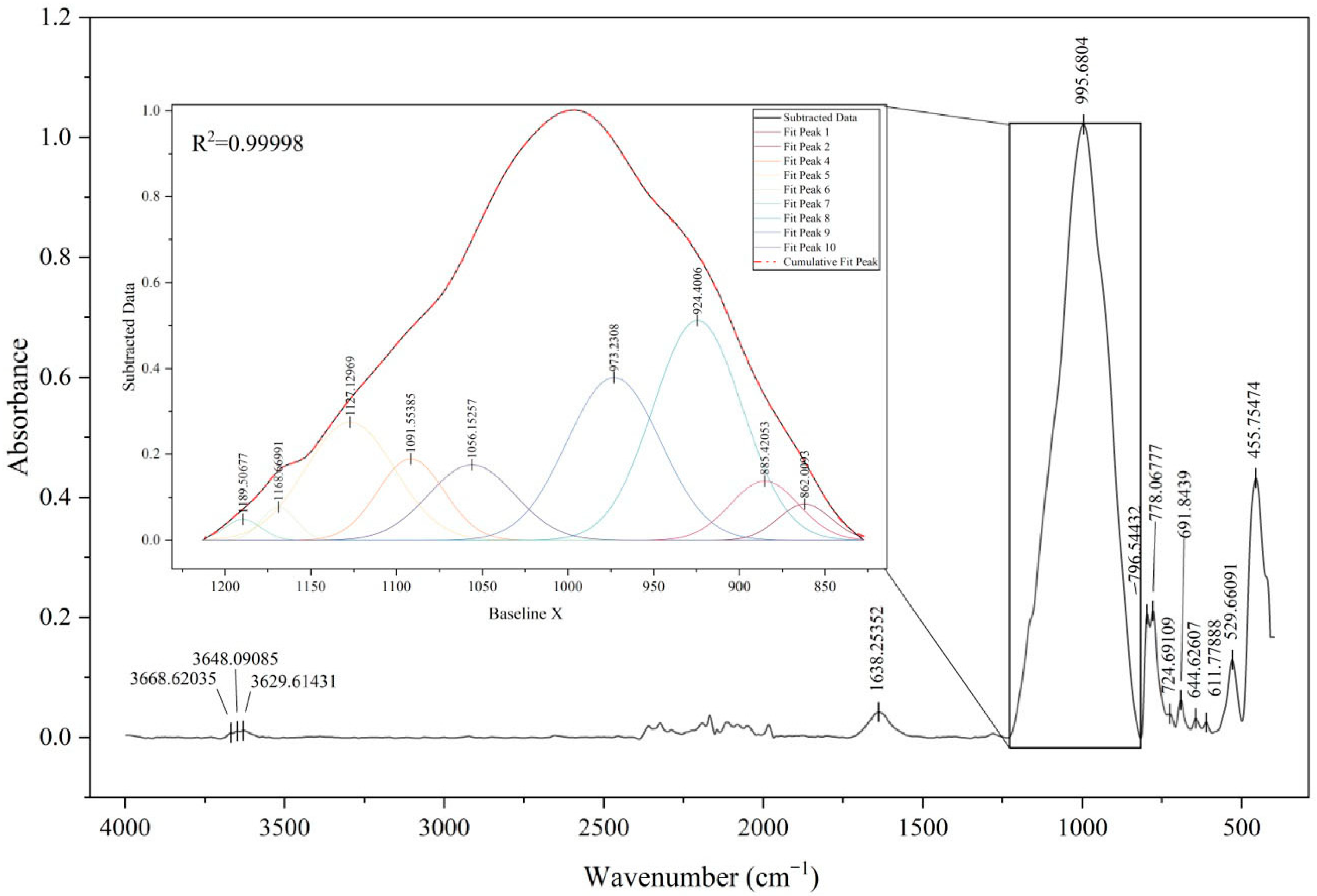

2.3.2. Mineral Composition Analysis Using ATR-FTIR

2.3.3. Characteristics of Ceramic Material

3. Experimental

3.1. Analyzed Pottery Description

3.2. Reagents

3.3. Instruments

3.4. Sample Preparation and Analytical Procedures

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATR | attenuated total reflectance |

| FTIR | fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| HPLC-ICP hrOES | high-performance liquid chromatography–inductively coupled plasma high-resolution optical emission spectrometry |

| PCA | principal components analysis |

| PDCA | pyridine–2,6–dicarboxylic acid |

| PEEK | polyetheretherketone |

| UV-Vis | ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometry |

| XRF | X-ray fluorescence spectrometry |

References

- Forster, N.; Grave, P.; Vickery, N.; Kealhofer, L. Non-destructive analysis using PXRF: Methodology and application to archaeological ceramics. X-Ray Spectrom. 2011, 40, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michałowski, A.; Niedzielski, P.; Kozak, L.; Teska, M.; Jakubowski, K.; Żółkiewski, M. Archaeometrical studies of prehistoric pottery using portable ED-XRF. Measurement 2020, 159, 107758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, V.; Morgenstein, M. Portable EDXRF analysis of a mud brick necropolis enclosure: Evidence of work organization, El Hibeh, Middle Egypt. J. Archaeo. Sci. 2007, 34, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gojska, A.M.; Mista-Jakubowska, E.A.; Banas, D.; Kubala-Kukus, A.; Stabrawa, I. Archaeological applications of spectroscopic measurements. Compatibility of analytical methods in comparative measurements of historical Polish coins. Measurement 2019, 135, 869–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karydas, A.; Kotzamani, D.; Bernard, R.; Barrandon, J.; Zarkadas, C. A compositional study of a museum jewellery collection (7th–1st BC) by means of a portable XRF spectrometer. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2004, 226, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergenc, D.; Fort, R. Multi-technical characterization of Roman mortars from Complutum, Spain. Measurement 2019, 147, 106876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezzerini, M.; Raneri, S.; Pagnotta, S.; Columbu, S.; Gallello, G. Archaeometric study of mortars from the Pisa’s Cathedral Square (Italy). Measurement 2018, 126, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosado, L.; Van Pevenage, J.; Vandenabeele, P.; Candeias, A.; Conceição Lopes, M.; Tavares, D.; Alfenim, R.; Schiavon, N.; Mirão, J. Multi-analytical study of ceramic pigments application in the study of Iron Age decorated pottery from SW Iberia. Measurement 2018, 118, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szokefalvi-Nagy, Z.; Demeter, I.; Kocsonya, A.; Kovacs, I. Non-destructive XRF analysis of paintings. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2004, 226, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, F.P.; Pappalardo, G.; Pappalardo, L.; Garraffo, S.; Gigli, R.; Pautasso, A. Quantitative non-destructive determination of trace elements in archaeological pottery using a portable beam stability-controlled XRF spectrometer. X-Ray Spectrom. 2006, 35, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speakman, R.J.; Little, N.C.; Creel, D.; Miller, M.R.; Inanez, J.G. Sourcing ceramics with portable XRF spectrometers? A comparison with INAA using Mimbres pottery from the American Southwest. J. Archaeo. Sci. 2011, 38, 3483–3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonizzoni, L.; Galli, A.; Milazzo, M. XRF analysis without sampling of Etruscan depurata pottery for provenance classification. X-Ray Spectrom. 2010, 39, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, D.; Webb, J.M. Pottery production and distribution in prehistoric Bronze Age Cyprus. An application of pXRF analysis. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2012, 39, 1380–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenstein, M.; Redmount, C.A. Using portable energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence (EDXRF) analysis for on-site study of ceramic sherds at El Hibeh, Egypt. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2005, 32, 1613–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babetto, M.; Lazzarini, L.; Rova, E.; Visona, D. Archaeometric analyses of Early Bronze Age pottery from Khashuri Natsargora (Georgia). J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2021, 35, 102700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitriu, I.; Fierascu, R.C.; Bunghez, R.I.; Pop, S.F.; Doncea, S.M.; Ion, M.L.; Ion, R.M. Analytical Methods for Artefacts Complex Analysis. Rev. Roum. Chim. 2011, 56, 931–940. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes de Soto, M.; de Soto, I.S.; García, R. Archaeometrical Study of Second Iron Age Ceramics from the Northwestern of the Iberian Peninsula. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 2014, 14, 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Calparsoro, E.; Sanchez-Garmendia, U.; Arana, G.; Maguregui, M.; Inanez, J.G. An archaeometric approach to the majolica pottery from alcazar of Najera archaeological site. Herit. Sci. 2019, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montana, G.; Randazzo, L.; Blasetti Fantauzzi, C. Archaeometric Characterization of Late Archaic Ceramic from Erice (Sicily) Aimed to Provenance Determination. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2019, 10, 605–622. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Zhao, J.; Collerson, K.D.; Greig, A. Application of ICP-MS trace element analysis in study of ancient Chinese ceramics. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2003, 48, 1219–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triadan, D.; Neff, H.; Glascock, M.D. An Evaluation of the Archaeological Relevance of Weak-Acid Extraction ICP: White Mountain Redware as a Case Study. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1997, 24, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardelli, F.; Maisano, G.; Barone, G.; Majolino, D.; Crupi, V.; Longo, F.; Mazzoleni, P.; Venuti, V. Iron speciation in ancient Attic pottery pigments: A non-destructive SR-XAS investigation. J. Synchrotron Rad. 2012, 19, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floresta, D.; Ardisson, J.; Fagundes, M.; Fabris, J.; Macedo, W. Oxidation states of iron as an indicator of the techniques used to burn clays and handcraft archaeological Tupiguarani ceramics by ancient human groups in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Hyperfine Interact. 2014, 224, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domenech-Carbo, A.; Yusa-Marco, D.J.; Sanchez-Ramosa, S.; SaurÌ-Peris, M.C. Electrochemical Determination of the Fe(III)/Fe(II) Ratio in Archaeological Ceramic Materials Using Carbon Paste and Composite Electrodes. Electroanalysis 2002, 14, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, L.; Michałowski, A.; Proch, J.; Krueger, M.; Munteanu, O.; Niedzielski, P. Iron forms Fe(II) and Fe(III) determination in Pre-Roman Iron Age archaeological pottery as a new tool in archaeometry. Molecules 2021, 26, 5617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orecchio, S. Speciation studies of iron in ancient pots from Sicily (Italy). Microchem. J. 2011, 99, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proch, J.; Niedzielski, P. Iron species determination by high performance liquid chromatography with plasma based optical emission detectors: HPLC–MIP OES and HPLC–ICP OES. Talanta 2021, 231, 122403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrizi, G.; Vagnini, M.; Vivani, R.; Fiorini, R.; Miliani, C. Archaeometric study of Etruscan scarab gemstones by non-destructive chemical and topographical analysis. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2016, 8, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Wang, Z.; Shen, S.; Xia, Y.; Li, Y.; Hu, D. Blurring of ancient wall paintings caused by binder decay in the pigment layer. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karydis, C.; Oikonomou, A.; Konstanta, A. The unpublished coptic textiles of the monastery of St. John the Theologian: Preliminary results of previous alterations and scientific analysis. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 2019, 19, 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Gomathy, Y.; Chandrasekaran, A.; Aravinthraj, M.; Udayaseelan, J. A preliminary study of ancient potteries collected from Kundureddiyur, Tamil Nadu, India. Microchem. J. 2021, 165, 106100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, T.; Carter, J.C.; Swift, K. SEM-EDX and FTIR analysis of archaeological ceramic potteries from southern Italy. Microscopy 2020, 69, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grifa, C.; Germinario, C.; De Bonis, A.; Cavassa, L.; Izzo, F.; Mercurio, M.; Langella, A.; Kakoulli, I.; Fischer, C.; Barra, D.; et al. A pottery workshop in Pompeii unveils new insights on the Roman ceramics crafting tradition and raw materials trade. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2021, 126, 105305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravisankar, R.; Raja Annamalai, G.; Naseerutheen, A.; Chandrasekaran, A.; Prasad, M.V.R.; Satpathy, K.K.; Maheswaran, C. Analytical characterization of recently excavated megalithic sarcophagi potsherds in Veeranam village, Tiruvannamalai dist., Tamilnadu, India. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2013, 115, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarquini, G.; Nunziante Cesaro, S.; Campanella, L. Identification of oil residues in Roman amphorae (Monte Testaccio, Rome): A comparative FTIR spectroscopic study of archeological and artificially aged samples. Talanta 2014, 118, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Benedetto, G.E.; Fabbri, B.; Gualtieri, S.; Sabbatini, L.; Zambonin, P.G. FTIR-chemometric tools as aids for data reduction and classification of pre-Roman ceramics. J. Cult. Herit. 2005, 6, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakosta, V. Multimethod (FTIR, XRD, pXRF) analysis of Ertebolle pottery ceramics from Scania, southern Sweden. Archaeometry 2020, 62, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Polo, A.; Briceno, S.; Jamett, A.; Galeas, S.; Campana, O.; Guerrero, V.; Arroyo, C.R.; Debut, A.; Mowbray, D.J.; Zamora-Ledezma, C.; et al. An Archaeometric Characterization of Ecuadorian Pottery. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennett, D.J.; Sakai, S.; Neff, H.; Gossett, R.; Larson, D.O. Compositional Characterization of Prehistoric Ceramics: A New Approach. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2002, 29, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paama, L.; Pitkanen, I.; Peramaki, P. Analysis of archaeological samples and local clays using ICP-AES, TG–DTG and FTIR techniques. Talanta 2000, 51, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madejová, J. FTIR techniques in clay mineral studies. Vib. Spectrosc. 2003, 31, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R.L.; Vassallo, A.M. The Dehydroxylation of the Kaolinite Clay Minerals using Infrared Emission Spectroscopy. Clays Clay Min. 1996, 44, 635–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, M.; Singh, L. Vibrational spectroscopic study of muscovite and biotite layered phyllosilicates. Indian J. Pure Appl. Phys. 2016, 54, 116–122. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, D.M. Empirical study of the infrared lattice vibrations (1100-350 cm-1) of phlogopite. Phys. Chem. Miner. 1989, 16, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivoshein, P.K.; Volkov, D.S.; Rogova, O.B.; Proskurnin, M.A. FTIR Photoacoustic and ATR Spectroscopies of Soils with Aggregate Size Fractionation by Dry Sieving. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 2177–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akyuz, S.; Akyuz, T.; Basaran, S.; Bolcal, C.; Gulec, A. Analysis of ancient potteries using FT-IR, micro-Raman and EDXRF spectrometry. Vib. Spectrosc. 2008, 48, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Skinner, W.; Addai-Mensah, J. Leaching behaviour of low and high Fe-substituted chlorite clay minerals at low pH. Hydrometallurgy 2012, 125, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloprogge, J. Spectroscopic Methods in the Study of Kaolin Minerals and Their Modifications; Springer Mineralogy; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shoval, S. Using FT-IR spectroscopy for study of calcareous ancient ceramics. Opt. Mater. 2003, 24, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachenko, Y.; Niedzielski, P. FTIR as a Method for Qualitative Assessment of Solid Samples in Geochemical Research: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 8846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed Murthuza, K.; Surumbarkuzhali, N.; Thirukumaran, V.; Durai Ganesh Ravisankar, R.; Balasubramaniyan, G. The Use of Spectroscopy Techniques to Determine the Mineral Content of Soils in the Tiruvannamalai District of Tamil Nadu India. J. Rad. Nucl. Appl. 2023, 8, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, P.S.R.; Shiva Prasad, K.; Krishna Chaitanya, V.; Babu, E.V.S.S.K.; Sreedhar, B.; Ramana Murthy, S. In situ FTIR study on the dehydration of natural goethite. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2006, 27, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklute, E.C.; Kashyap, S.; Dyar, M.D.; Holden, J.F.; Tague, T.; Wang, P.; Jaret, S.J. Spectral and morphological characteristics of synthetic nanophase iron (oxyhydr) oxides. Phys. Chem. Miner. 2018, 45, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanivel, R.; Rajesh Kumar, U. The mineralogical and fabric analysis of ancient pottery artifacts. Cerâmica 2011, 57, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Sharma, S. Thermal and spectroscopic characterization of archeological pottery from Ambari, Assam. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2016, 5, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedzielski, P.; Kozak, L. Iron’s fingerprint of deposits—Iron speciation as a geochemical marker. Environ. Sci Pollut. R 2018, 25, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczor, W.; Michałowski, A.; Teska, M.; Żółkiewski, M. Grabkowo district Kowal, sites 7 and 8. In Archaeological Sources for Studies on the Pre-Roman Period in the Wielkopolska-Kujawska Lowlands; Wydawnictwo Nauka i Innowacje: Poznań, Poland, 2017. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Lafuente, B.; Downs, R.T.; Yang, H.; Stone, N. The Power of Databases: The RRUFF Project. In Highlights in Mineralogical Crystallography; Armbruster, T., Danisi, R.M., Eds.; W. De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

| Vessel 1 | Si | Al | K | Fe | Ca | Ti | Ba | Mn |

| min | 73,600 | 7410 | 42,600 | 24,700 | 17,700 | 4830 | 715 | 332 |

| max | 345,000 | 114,000 | 68,500 | 81,100 | 37,600 | 10,300 | 16,500 | 847 |

| median | 305,000 | 92,100 | 56,400 | 48,600 | 25,000 | 7750 | 7790 | 523 |

| mean | 290,000 | 89,100 | 56,200 | 47,300 | 25,300 | 7680 | 7820 | 537 |

| SD | 55 | 18,700 | 5340 | 8370 | 3470 | 951 | 2650 | 107 |

| RSD% | 19 | 21 | 10 | 18 | 14 | 12 | 34 | 20 |

| max/min | 4.7 | 15 | 1.6 | 3.3 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 23 | 2.5 |

| Vessel 2 | Si | Al | K | Fe | Ca | Ti | Ba | Mn |

| min | 25,600 | 7810 | 2640 | 15,200 | 3780 | 1550 | 100 | 185 |

| max | 226,000 | 71,900 | 25,000 | 57,100 | 28,700 | 7620 | 4340 | 468 |

| median | 142,000 | 36,500 | 14,800 | 45,300 | 18,600 | 5420 | 1400 | 302 |

| mean | 139,000 | 36,700 | 14,700 | 44,500 | 18,400 | 5360 | 1580 | 305 |

| SD | 45,500 | 13,200 | 4850 | 6170 | 3960 | 916 | 1070 | 52 |

| RSD% | 33 | 36 | 33 | 14 | 22 | 17 | 68 | 17 |

| max/min | 8.8 | 9.2 | 9.5 | 3.8 | 7.6 | 4.9 | 43 | 2.5 |

| Outer Part | Si | Al | K | Fe | Ca | Ti | Ba | Mn |

| min | 127,000 | 35,000 | 6500 | 26,900 | 2110 | 1620 | 11 | 316 |

| max | 240,000 | 84,200 | 22,400 | 53,200 | 8810 | 4030 | 427 | 1290 |

| median | 204,000 | 56,400 | 17,900 | 46,300 | 5960 | 3190 | 103 | 512 |

| mean | 201,000 | 57,300 | 16,800 | 44,900 | 5780 | 3070 | 119 | 588 |

| SD | 26,400 | 9580 | 3710 | 6440 | 1610 | 545 | 71 | 229 |

| RSD% | 13 | 17 | 22 | 14 | 28 | 18 | 60 | 39 |

| max/min | 2.0 | 2.4 | 3.4 | 2.0 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 39 | 4.1 |

| Inner Part | Si | Al | K | Fe | Ca | Ti | Ba | Mn |

| min | 170,000 | 51,800 | 9732 | 23,400 | 1950 | 2200 | 48 | 175 |

| max | 278,100 | 84,600 | 15,100 | 40,800 | 5030 | 4330 | 1350 | 969 |

| median | 211,000 | 65,800 | 12,851 | 33,300 | 4230 | 3480 | 180 | 272 |

| mean | 215,000 | 66,800 | 12,788 | 33,900 | 4000 | 3350 | 237 | 330 |

| SD | 28,000 | 7490 | 1396 | 4280 | 805 | 552 | 160 | 168 |

| RSD% | 13 | 11 | 11 | 13 | 20 | 16 | 67 | 51 |

| max/min | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 2.0 | 28 | 5.5 |

| Si | Al | K | Fe | Ca | Ti | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| min | 234,000 | 99,000 | 10,900 | 20,600 | 4510 | 2890 |

| max | 308,000 | 177,000 | 30,100 | 73,400 | 44,600 | 5200 |

| median | 266,000 | 144,000 | 19,100 | 46,500 | 14,900 | 3730 |

| mean | 268,000 | 143,000 | 18,700 | 46,600 | 16,900 | 3810 |

| SD | 15,200 | 13,200 | 3700 | 11,500 | 8090 | 451 |

| RSD% | 6 | 9 | 20 | 25 | 48 | 12 |

| max/min | 1.3 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 3.6 | 9.9 | 1.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kozak, L.; Michałowski, A.; Tkachenko, Y.; Proch, J.; Jasiewicz, J.; Niedzielski, P. Multi-Techniques Analysis of Archaeological Pottery—Potential Pitfalls in Interpreting the Results. Molecules 2025, 30, 4732. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244732

Kozak L, Michałowski A, Tkachenko Y, Proch J, Jasiewicz J, Niedzielski P. Multi-Techniques Analysis of Archaeological Pottery—Potential Pitfalls in Interpreting the Results. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4732. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244732

Chicago/Turabian StyleKozak, Lidia, Andrzej Michałowski, Yana Tkachenko, Jędrzej Proch, Jarosław Jasiewicz, and Przemysław Niedzielski. 2025. "Multi-Techniques Analysis of Archaeological Pottery—Potential Pitfalls in Interpreting the Results" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4732. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244732

APA StyleKozak, L., Michałowski, A., Tkachenko, Y., Proch, J., Jasiewicz, J., & Niedzielski, P. (2025). Multi-Techniques Analysis of Archaeological Pottery—Potential Pitfalls in Interpreting the Results. Molecules, 30(24), 4732. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244732