Study on the Structure of Lignin Isolated from Wood Under Acidic Conditions

Abstract

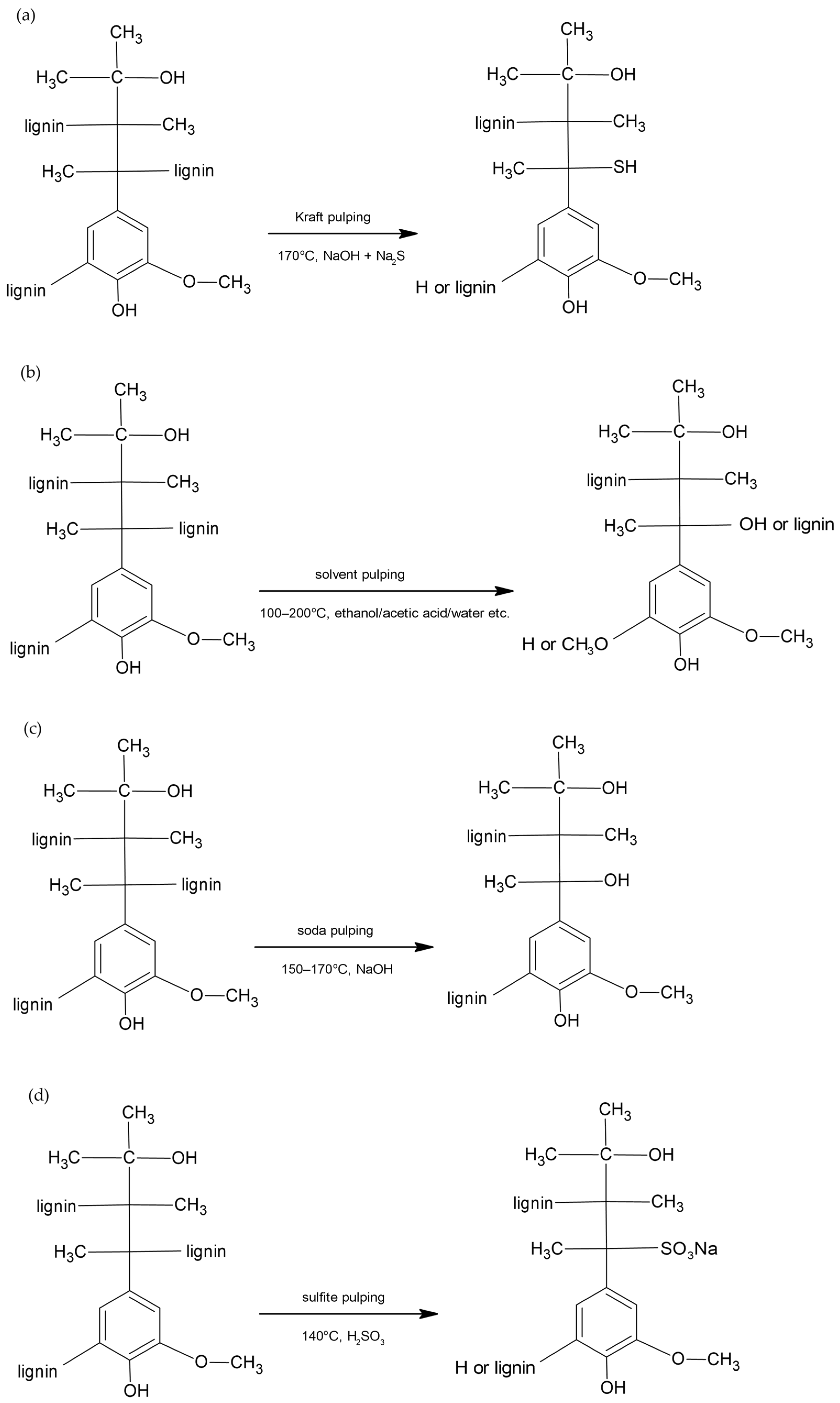

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

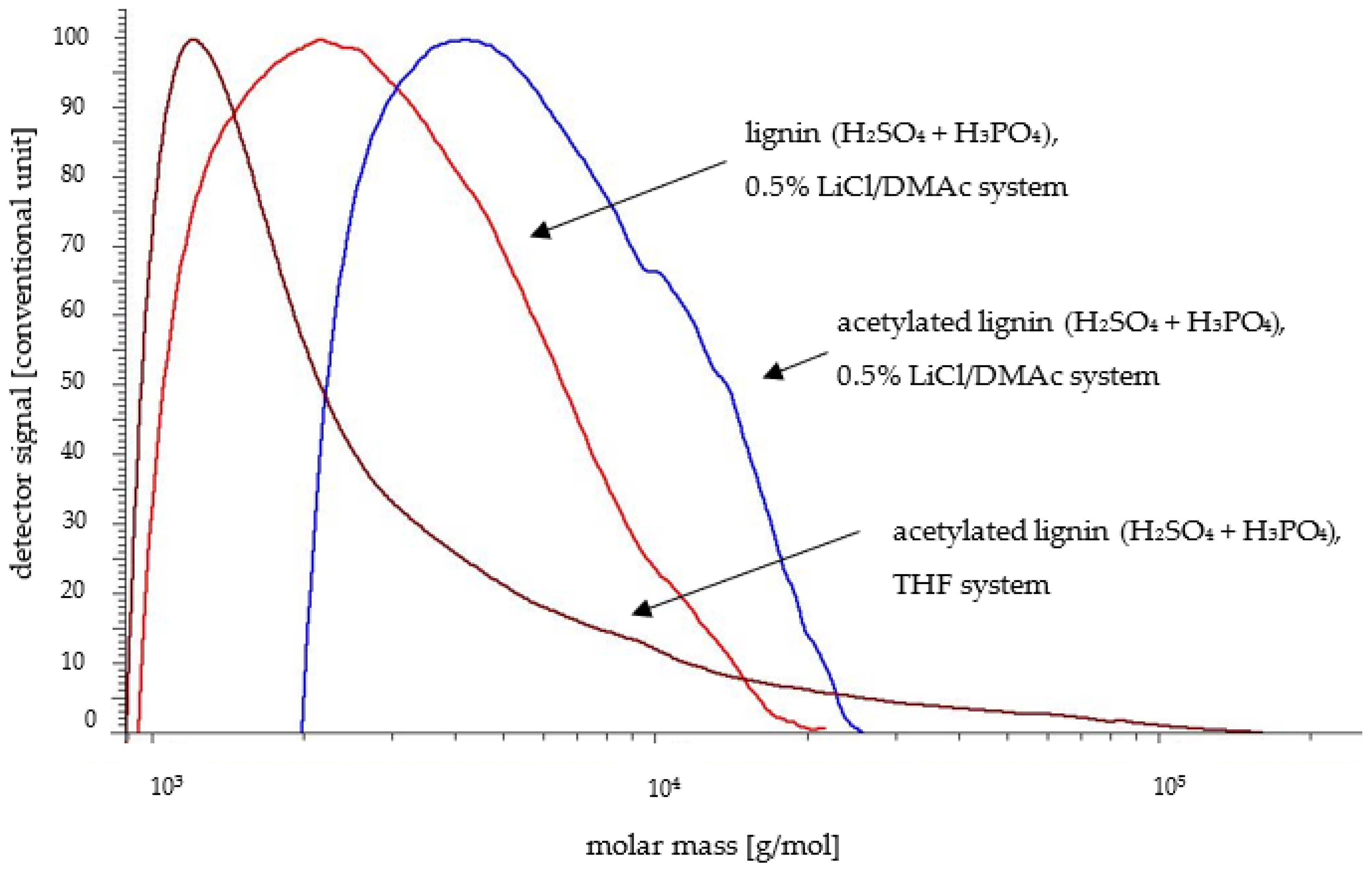

2.1. SEC Analysis

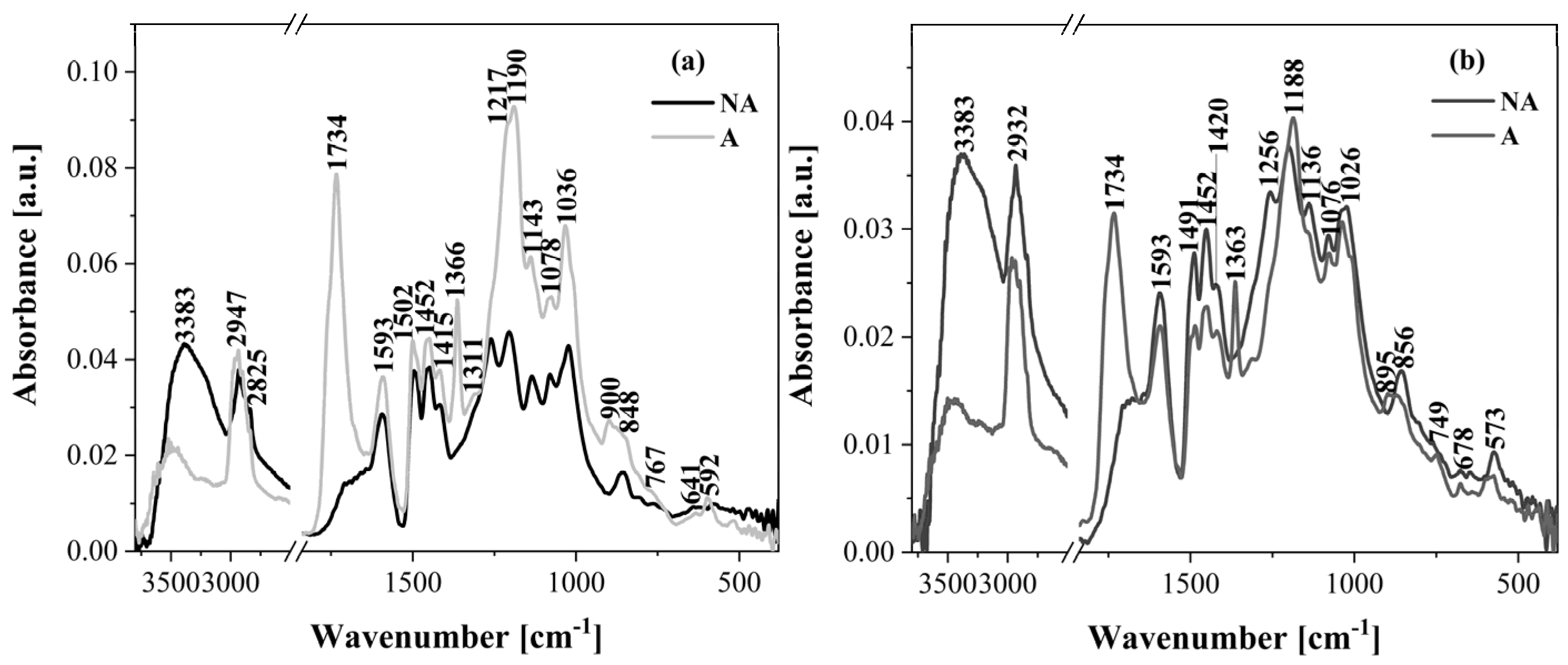

2.2. ATR-FTIR Analysis

2.3. SEM Analysis

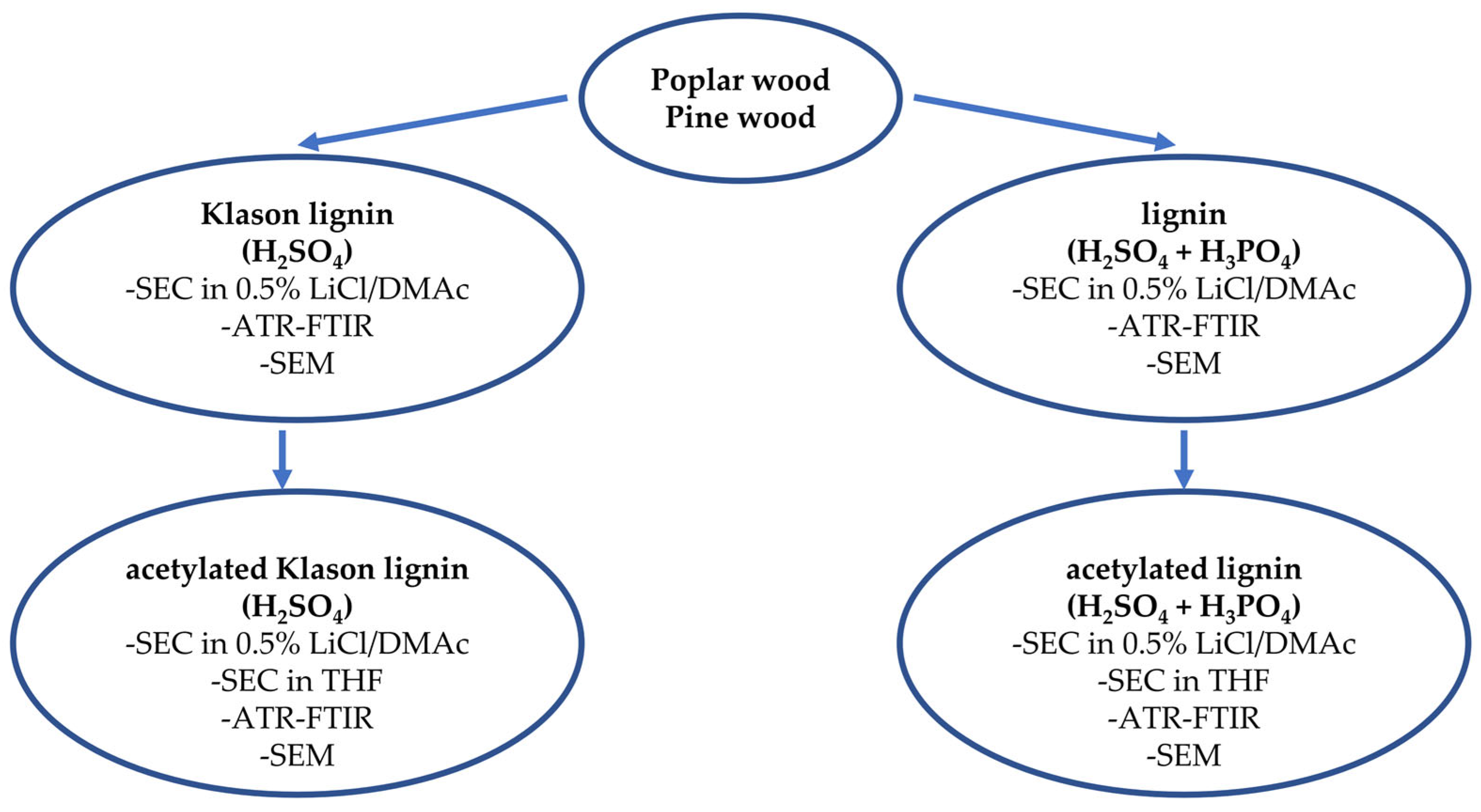

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Material Characteristics

3.2. Research Methods

3.2.1. Lignin Isolation Method in Acidic Conditions

3.2.2. Lignin Acetylation

3.2.3. Acetylated Lignin Dissolution for SEC Analysis

- A total of 10 mg of acetylated lignin sample was weighed in an Eppendorf tube;

- Next, 1 cm3 of THF was added, and the test tubes were closed;

- The lignin sample dissolution over 1 h was carried out using a rotary mixer (RM-2M, Elmi, Calabasas, CA, USA);

- After dissolution, the samples were filtered using a 0.22 µm nylon syringe filter;

- Finally, for each sample, three SEC analyses were performed.

- A total of 10 mg of acetylated lignin sample was weighed in a glass screw-cap tube with a volume of 10 cm3;

- Next, 5 cm3 of 0.5% LiCl/DMAc was added, and the test tubes were screwed tight;

- The lignin sample dissolution over 7 days was carried out using a rotary mixer (RM-2M, Elmi, Calabasas, CA, USA);

- After dissolution, the samples were filtered using a 0.22 µm nylon syringe filter;

- Finally, for each sample, three SEC analyses were performed.

3.2.4. SEC Analysis

3.2.5. ATR-FTIR Analysis

3.2.6. SEM Analysis

4. Conclusions

- Lignin isolated from poplar and pine wood in acidic conditions had a highly condensed structure, which was confirmed by SEC, ATR-FTIR, and SEM techniques.

- The SEC analysis of acetylated lignin in the 0.5% LiCl/DMAc system indicated that the determined parameters (Mn, Mw, and PDI) were more reliable than in THF regardless of the isolation method. The weight of the average molar mass was up to 118,700 g/mol and was much higher for the acetylated lignin isolated in acidic conditions from poplar wood than from pine wood. This is likely due to the limited solubility of highly condensed pine lignin in the 0.5% LiCl/DMAc system. Particularly interesting was the fact that, in this system after acetylation, more reliable results were obtained for condensed poplar lignin.

- The ATR-FTIR analysis confirmed that the lignin acetylation reaction was successful, and in all lignin spectra characteristic signals corresponding to methoxy groups, phenolic hydroxyl groups, and aromatic rings were observed. Moreover, this technique is a useful method for monitoring lignin condensation phenomena. Lignin obtained in acidic conditions also can be used for different value-added applications.

- The SEM technique confirmed that the tested lignin samples, isolated in acidic conditions, showed the characteristics of condensed lignin. It was especially visible for pine lignin, as its particles were bigger and less degraded. The occurrence of precipitates on the lignin surface and also the presence of aggregates and agglomerates proved these observations. After acetylation, the surface image of lignin became more uniform and homogeneous.

- Condensed lignin, despite some of its limitations connected mainly with its complex and diverse chemical structure, is a valuable substance that can be used for different applications (carbon fibers or as an additive for thermoplastic blends). However, to be able to use lignin on an industrial scale in the future, further research and development are needed.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vermarris, W.; Nicholson, R. Phenolic Compound Biochemistry; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Heitner, C.; Dimmel, D.; Schmidt, J. Lignins and Lignans: Advances in Chemistry; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Boerjan, W.; Ralph, J.; Baucher, M. Lignin Biosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2003, 54, 519–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börcsök, Z.; Pásztory, Z. The Role of Lignin in Wood Working Processes Using Elevated Temperatures: An Abbreviated Literature Survey. Eur. J. Wood Prod. 2021, 79, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riseh, R.S.; Fathi, F.; Lagzian, A.; Vatankhah, M.; Kennedy, J.F. Modifying lignin: A promising strategy for plant disease control. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 271, 132696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, N.H.; Selvaraj, G.; Wei, Y.; King, J. Role of Lignification in Plant Defense. Plant Signal. Behav. 2009, 4, 158–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowell, R.M.; Pettersen, R.; Han, J.S.; Rowell, J.S.; Tshabalala, M.A. Cell wall chemistry. In Handbook of Wood Chemistry and Wood Composites; Rowell, R.M., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; pp. 35–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ganewatta, M.S.; Lokupitiya, H.N.; Tang, C. Lignin Biopolymers in the Age of Controlled Polymerization. Polymers 2019, 11, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novaes, E.; Kirst, M.; Chiang, V.; Winter-Sederoff, H.; Sederoff, R. Lignin and biomass: A negative correlation for wood formation and lignin content in trees. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Barrett, D.M.; Delwiche, M.J.; Stroeve, P. Methods for pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for efficient hydrolysis and biofuel production. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 3713–3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Dixon, R.A. Lignin modification improves fermentable sugar yields for biofuel production. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 759–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klapiszewski, Ł. Funkcjonalne materiały otrzymywane z udziałem ligniny—Od projektowania do zastosowania. Wiadomości Chem. 2021, 75, 1155–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goliaszek-Chabros, M.; Xu, T.; Bocho-Janiszewska, A.; Podkościelna, B.; Sevastyanova, O. Lignin nanoparticles from softwood and hardwood as sustainable additives for broad-spectrum protection and enhanced sunscreen performance. Wood Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jääskeläinen, A.-S.; Sun, Y.; Tamminen, T.; Hortling, B. The Effect of Isolation Method on the Chemical Structure of Residual Lignin. Wood Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, H.; Decina, S.; Crestini, C. Oxidative Upgrade of Lignin—Recent Routes Reviewed. Eur. Polym. J. 2013, 49, 1151–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolbert, A.; Akinosho, H.; Khunsupat, R.; Naskar, A.K.; Ragauskas, A.J. Characterization and analysis of the molecular weight of lignin for biorefining studies. Biofuel. Bioprod. Biorefining 2014, 8, 836–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.; Wei, L.; Li, W.; Gong, D.; Qin, H.; Feng, X.; Li, G.; Ling, Z.; Wang, P.; Yin, B. Isolating High Antimicrobial Ability Lignin from Bamboo Kraft Lignin by Organosolv Fractionation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 683796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruwoldt, J.; Blindheim, F.H.; Chinga-Carrasco, G. Functional surfaces, films, and coatings with lignin—A critical review. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 12529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadan, R.; Alaoui, C.H.; Ihammi, A.; Chigr, M.; Fatimi, A. A Brief Overview of Lignin Extraction and Isolation Processes: From Lignocellulosic Biomass to Added-Value Biomaterials. Environ. Earth Sci. Proc. 2024, 31, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TAPPI T222 om-02; Acid-Insoluble Lignin in Wood and Pulp. TAPPI Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2006.

- Beňo, E.; Góra, R.W.; Hutta, M. Characterization of Klason Lignin Samples Isolated from Beech and Aspen Using Microbore Column Size-Exclusion Chromatography. J. Sep. Sci. 2018, 41, 3195–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaka, R.K.; Sinha, S.K.; Gunaga, R.P.; Thakur, N.S. Modification in protocol for estimation of Klason-lignin content by gravimetric method. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 2019, 7, 2661–2664. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, W.; Luterbacher, J.S. Preventing Lignin Condensation to Facilitate Aromatic Monomer Production. Chimia 2019, 73, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skręta, A.; Antczak, A. SEC analysis of the molar mass of lignin isolated from poplar (Populus deltoides × maximowiczii) and Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) wood. Ann. Wars. Univ. Life Sci. For. Wood Technol. 2024, 125, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shuai, L.; Kim, H.; Motagamwala, A.H.; Mobley, J.K.; Yue, F.; Tobimatsu, Y.; Havkin-Frenkel, D.; Chen, F.; Dixon, R.A.; et al. An “ideal lignin” facilitates full biomass utilization. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaau2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Xiao, T.; Guo, Y.; Fatehi, P.; Sun, Y.; Niu, M.; Shi, H. Reveling the mechanism of lignin modification by phenolic additives during pre-hydrolysis treatment and its effect on enzymatic hydrolysis. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2024, 209, 118063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K.; Hosoya, S.; Ikeda, T. Condensation Reactions of Softwood and Hardwood Lignin Model Compounds Under Organic Acid Cooking Conditions. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 1997, 17, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Pud, Y.; Ragauskas, A.; Yang, B. From lignin to valuable products–strategies, challenges, and prospects. Bioresource Technol. 2019, 271, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolore, R.S.; Jaiswal, S.; Jaiswal, A.K. A comprehensive review on sustainable lignin extraction techniques, modifications, and emerging applications. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2025, 235, 121696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipko, T.; Donchenko, M.; Prysiazhnyi, Y.; Mnykh, R.; Pochapska, I.; Pyshyev, S. Study on the Technical Lignin Effect on the Road Bitumen Properties. Chem. Chem. Technol. 2025, 19, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinovyev, G.; Sulaeva, I.; Podzimek, S.; Rössner, D.; Kilpeläinen, I.; Sumerskii, I.; Rosenau, T.; Potthast, A. Getting Closer to Absolute Molar Masses of Technical Lignins. ChemSusChem 2018, 11, 3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansouri, N.E.; Salvadó, J. Structural Characterization of Technical Lignins for the Production of Adhesives: Application to Lignosulfonate, Kraft, Soda-Anthraquinone, Organosolv and Ethanol Process Lignins. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2006, 24, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumberger, S.; Abaecherli, A.; Fasching, M.; Gellerstedt, G.; Gosselink, R.; Hortling, B.; Li, J.; Saake, B.; de Jong, E.M. Molar mass determination of lignins by size-exclusion chromatography: Towards standardisation of the method. Holzforschung 2007, 61, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; He, J.; Narron, R.; Wang, Y.; Yong, Q. Characterization of Kraft Lignin Fractions Obtained by Sequential Ultrafiltration and Their Potential Application as a Biobased Component in Blends with Polyethylene. ACS Sust. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 11770–11779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Sampedro, R.; Santos, J.I.; Fillat, Ú.; Wicklein, B.; Eugenio, M.E.; Ibarra, D. Characterization of Lignins from Populus alba L. Generated as By-Products in Different Transformation Processes: Kraft Pulping, Organosolv and Acid Hydrolysis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 126, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diment, D.; Tkachenko, O.; Schlee, P.; Kohlhuber, N.; Potthast, A.; Budnyak, T.; Rigo, D.; Balakshin, M. Study toward a more reliable approach to elucidate the lignin structure–property–performance correlation. Biomacromolecules 2023, 25, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shayesteh, K.; Mohammadzadeh, Q. Stepwise Removal of Lignin Sulfonate Hydroxyl Ion to Reduce Its Solubility in an Aqueous Environment: As a Coating in Slow-Release Systems or Absorbent Base. Chem. Rev. Lett. 2023, 6, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiskari, J.; Derkacheva, O.; Kulomaa, T.; Sukhov, D. Quick non-destructive analysis of lignin condensation and precipitation by FTIR. Cellulose Chem. Technol. 2016, 50, 213–217. [Google Scholar]

- Fiskari, J.; Derkacheva, O.; Kulomaa, T. Quick non-destructive analysis of condensed lignin by FTIR. Part 2. Pulp samples from acid sulfite cooking. Cellulose Chem. Technol. 2021, 55, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, W.O.S.; Mousavioun, P.; Fellows, C.M. Value-adding to cellulosic ethanol: Lignin polymers. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2011, 33, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suota, M.J.; Kochepka, D.M.; Ganter Moura, M.G.; Pirich, C.L.; Matos, M.; Magalhães, W.L.E.; Ramos, L.P. Lignin functionalization strategies and the potential applications of its derivatives—A review. BioResources 2021, 16, 6471–6511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameni, J.; Krigstin, S.; Sain, M. Solubility of lignin and acetylated lignin in organic solvents. BioResources 2017, 12, 1548–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringena, O.; Lebioda, S.; Lehnen, R.; Saake, B. Size-Exclusion Chromatography of Technical Lignins in Dimethyl Sulfoxide/Water and Dimethylacetamide. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1102, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esakkimuthu, E.S. Study of New Chemical Derivatization Techniques for Lignin Analysis by Size Exclusion Chromatography. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Grenoble Alpes, Grenoble, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gosselink, R.J.A.; Abächerli, A.; Semke, H.; Malherbe, R.; Käuper, P.; Nadif, A.; van Dam, J.E.G. Analytical protocols for characterisation of sulphur-free lignin. Ind. Crops Prod. 2004, 19, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannigrahi, P.; Ragauskas, A.J.; Miller, S.J. Lignin Structural Modifications Resulting from Ethanol Organosolv Treatment of Loblolly Pine. Energy Fuels 2010, 24, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Shin, E.-J.; Eom, I.-Y.; Won, K.; Kim, Y.H.; Choi, D.; Choi, I.-G.; Choi, J.W. Structural features of lignin macromolecules extracted with ionic liquid from poplar wood. Bioresource Technol. 2011, 102, 9020–9025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faix, O. Fourier transformed infrared spectroscopy. In Methods in Lignin Chemistry; Lin, S.Y., Dence, C.W., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992; pp. 458–464. [Google Scholar]

- Lisperguer, J.; Perez, P.; Urizar, S. Structure and thermal properties of lignins: Characterization by infrared spectroscopy and differential scanning calorimetry. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2009, 54, 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.; Skrifvars, M.; Kadi, N.; Dhakal, H.N. Effect of lignin acetylation on the mechanical properties of lignin-poly-lactic acid biocomposites for advanced applications. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2023, 202, 117049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammons, R.J.; Harper, D.P.; Labbé, N.; Bozell, J.J.; Elder, T.; Rials, T.G. Characterization of Organosolv Lignins using Thermal and FT-IR Spectroscopic Analysis. BioResources 2013, 8, 2752–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pua, F.; Fang, Z.; Zakaria, S.; Guo, F.; Chia, C. Direct production of biodiesel from high-acid value Jatropha oil with solid acid catalyst derived from lignin. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2011, 4, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bula, K.; Jędrzejczak, P.; Ajnbacher, D.; Collins, M.N.; Klapiszewski, Ł. Design and characterization of functional TiO2–lignin fillers used in rotational molded polyethylene containers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 246, 125626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddighi, H.; Shayesteh, K.; Omrani, N. Acetylated lignin sulfonate as a biodegradable coating for controlled-release urea fertilizer: A novel acetylation method and diffusion coefficient analysis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Genco, J.; Cole, B.; Fort, R. Lignin recovered from the near-neutral hemicellulose extraction process as a precursor for carbon fiber. BioResources 2011, 6, 4566–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Brown, R.H.; Hunt, M.A.; Pickel, D.L.; Pickel, J.M.; Messman, J.M.; Baker, F.S.; Keller, M.; Naskar, A.K. Turning renewable resources into value-added polymer: Development of lignin-based thermoplastic. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 3295–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Perkins, J.H.; Jackson, D.C.; Trammel, N.E.; Hunt, M.A.; Naskar, A.K. Development of lignin-based polyurethane thermoplastics. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 21832–21840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahri, S.; Park, B.-D. Bio-crosslinking of oxidized hardwood kraft lignin as fully bio-based adhesives for wood bonding. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 309, 142907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antczak, A.; Radomski, A.; Zawadzki, J. Benzene substitution in wood analysis. Ann. Wars. Univ. Life Sci. For. Wood Technol. 2006, 73, 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- Sluiter, A.; Ruiz, R.; Scarlata, C.; Sluiter, J.; Templeton, D. Determination of Extractives in Biomass (NREL/TP-510–42619); National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2008.

- PN-74/P-50092; Raw Materials for the Pulp and Paper Industry, Wood, Chemical Analysis. Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 1992.

- Esakkimuthu, E.S.; Marlin, N.; Brochier-Salon, M.-C.; Mortha, G. Application of a Universal Calibration Method for True Molar Mass Determination of Fluoro-Derivatized Technical Lignins by Size-Exclusion Chromatography. AppliedChem 2022, 2, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Liu, W.; Zhao, J.; Fu, P. Experimental investigation into effects of lignin on sandy loess. Soils Found. 2023, 63, 101359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lignin | Mn [g/mol] | Mw [g/mol] | PDI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poplar wood | |||

| Klason lignin (H2SO4) | 8339 ± 233 * | 53,577 ± 2251 * | 6.4 ± 0.3 * |

| Lignin (H2SO4 + H3PO4) | 4126 ± 443 * | 8530 ± 618 * | 2.1 ± 0.1 * |

| Acetylated Klason lignin (H2SO4) | 11,470 ± 1604 | 118,700 ± 4597 | 10.5 ± 1.2 |

| Acetylated lignin (H2SO4 + H3PO4) | 5153 ± 586 | 10,897 ± 617 | 2.1 ± 0.1 |

| Pine wood | |||

| Klason lignin (H2SO4) | 4653 ± 824 * | 6092 ± 358 * | 1.3 ± 0.3 * |

| Lignin (H2SO4 + H3PO4) | 2278 ± 337 * | 3513 ± 425 * | 1.5 ± 0.0 * |

| Acetylated Klason lignin (H2SO4) | 4478 ± 625 | 7492 ± 214 | 1.7 ± 0.3 |

| Acetylated lignin (H2SO4 + H3PO4) | 4595 ± 488 | 6327 ± 465 | 1.4 ± 0.1 |

| Lignin | Mn [g/mol] | Mw [g/mol] | PDI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poplar wood | |||

| Acetylated Klason lignin (H2SO4) | 327 ± 19 | 10,846 ± 546 | 33.2 ± 0.4 |

| Acetylated lignin (H2SO4 + H3PO4) | 170 ± 26 | 1783 ± 161 | 10.6 ± 1.7 |

| Pine wood | |||

| Acetylated Klason lignin (H2SO4) | 1885 ± 73 | 6193 ± 32 | 3.3 ± 0.1 |

| Acetylated lignin (H2SO4 + H3PO4) | 1923 ± 30 | 5251 ± 153 | 2.7 ± 0.1 |

| Lignin Source | Peak Wavenumber [cm−1] | Band Assignment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Klason Lignin (H2SO4) | Acetylated Klason Lignin (H2SO4) | Lignin (H2SO4 + H3PO4) | Acetylated Lignin (H2SO4 + H3PO4) | ||

| Poplar wood | 3390 | 3390 ↓ 1 | 3376 | 3376 ↓ | O-H stretching |

| 2940 | 2940 | 2925 | 2925 | C-H stretching (methoxyl group) | |

| 2833 | 2833 | 2845 | 2845 | C-H stretching (methyl and methylene groups) | |

| - | 1734 ↑ 2 | - | 1738 ↑ | C=O unconjugated (carbonyl group) | |

| 1598 | 1598 | 1598 | 1598 | Aromatic skeletal vibrations | |

| 1495 | 1495 | 1491 | 1491 | Aromatic skeletal vibrations | |

| 1455 | 1455 | 1455 | 1455 | C-H deformation (methyl and methylene groups) | |

| 1418 | 1418 | 1418 | 1418 | Aromatic skeletal vibrations | |

| - | 1360 ↑ | - | 1363 ↑ | C-H bond (acetyl group) | |

| 1264 | - | 1262 | - | C-O stretching (guaiacyl unit) | |

| 1211 | - | 1211 | - | C-O stretching (phenolic hydroxyl group) | |

| - | 1185 ↑ | - | 1185 ↑ | C=O stretching (acetyl group) | |

| 1106 | 1106 | 1106 | 1106 | C-H deformation (syringyl unit) | |

| 1023 | 1023 | 1026 | 1026 | C-H deformation and C-O deformation (methoxyl group) | |

| 904 | 904 | 908 | 908 | C-H out of plane (aromatic ring) | |

| 847 | 847 | 851 | 851 | C-H out of plane (positions 2, 5, and 6 of guaiacyl unit) | |

| Pine wood | 3383 | 3383 ↓ | 3383 | 3383 ↓ | O-H stretching |

| 2947 | 2947 | 2932 | 2932 | C-H stretching (methoxyl group) | |

| 2825 | 2825 | 2825 | 2825 | C-H stretching (methyl and methylene groups) | |

| - | 1734 ↑ | - | 1734 ↑ | C=O unconjugated (carbonyl group) | |

| 1593 | 1593 | 1593 | 1593 | Aromatic skeletal vibrations | |

| 1502 | 1502 | 1491 | 1491 | Aromatic skeletal vibrations | |

| 1452 | 1452 | 1452 | 1452 | C-H deformation (methyl and methylene groups) | |

| 1415 | 1415 | 1420 | 1420 | Aromatic skeletal vibrations | |

| - | 1366 ↑ | - | 1363 ↑ | C-H bond (acetyl group) | |

| 1256 | - | 1256 | - | C-O stretching (guaiacyl unit) | |

| 1217 | - | 1217 | - | C-O stretching (phenolic hydroxyl group) | |

| - | 1190 ↑ | - | 1188 ↑ | C=O stretching (acetyl group) | |

| 1143 | 1143 | 1136 | 1136 | C-H deformation (guaiacyl unit) | |

| 1036 | 1036 | 1026 | 1026 | C-H deformation and C-O deformation (methoxyl group) | |

| 900 | 900 | 895 | 895 | C-H out of plane (aromatic ring) | |

| 848 | 848 | 856 | 856 | C-H out of plane (positions 2, 5, and 6 of guaiacyl unit) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Antczak, A.; Skręta, A.; Kamińska-Dwórznicka, A.; Rząd, K.; Matwijczuk, A. Study on the Structure of Lignin Isolated from Wood Under Acidic Conditions. Molecules 2025, 30, 4705. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244705

Antczak A, Skręta A, Kamińska-Dwórznicka A, Rząd K, Matwijczuk A. Study on the Structure of Lignin Isolated from Wood Under Acidic Conditions. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4705. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244705

Chicago/Turabian StyleAntczak, Andrzej, Aneta Skręta, Anna Kamińska-Dwórznicka, Klaudia Rząd, and Arkadiusz Matwijczuk. 2025. "Study on the Structure of Lignin Isolated from Wood Under Acidic Conditions" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4705. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244705

APA StyleAntczak, A., Skręta, A., Kamińska-Dwórznicka, A., Rząd, K., & Matwijczuk, A. (2025). Study on the Structure of Lignin Isolated from Wood Under Acidic Conditions. Molecules, 30(24), 4705. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244705