Extracts from By-Products of the Fruit and Vegetable Industry as Ingredients Improving the Properties of Cleansing Gels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Content of Soluble Solids and Antioxidants in Extracts

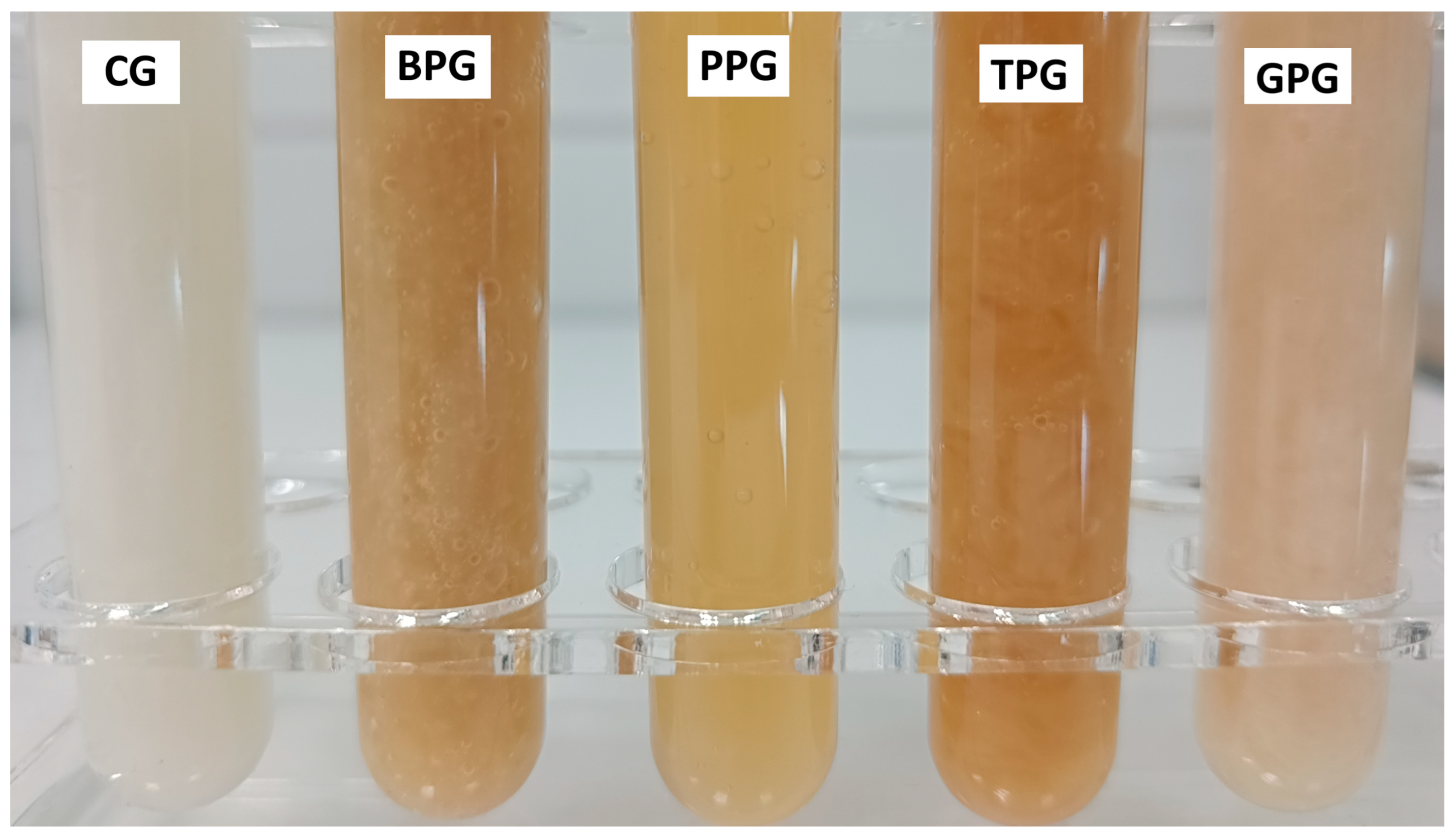

2.2. Characteristics of the Obtained Gels

3. Materials and Methods

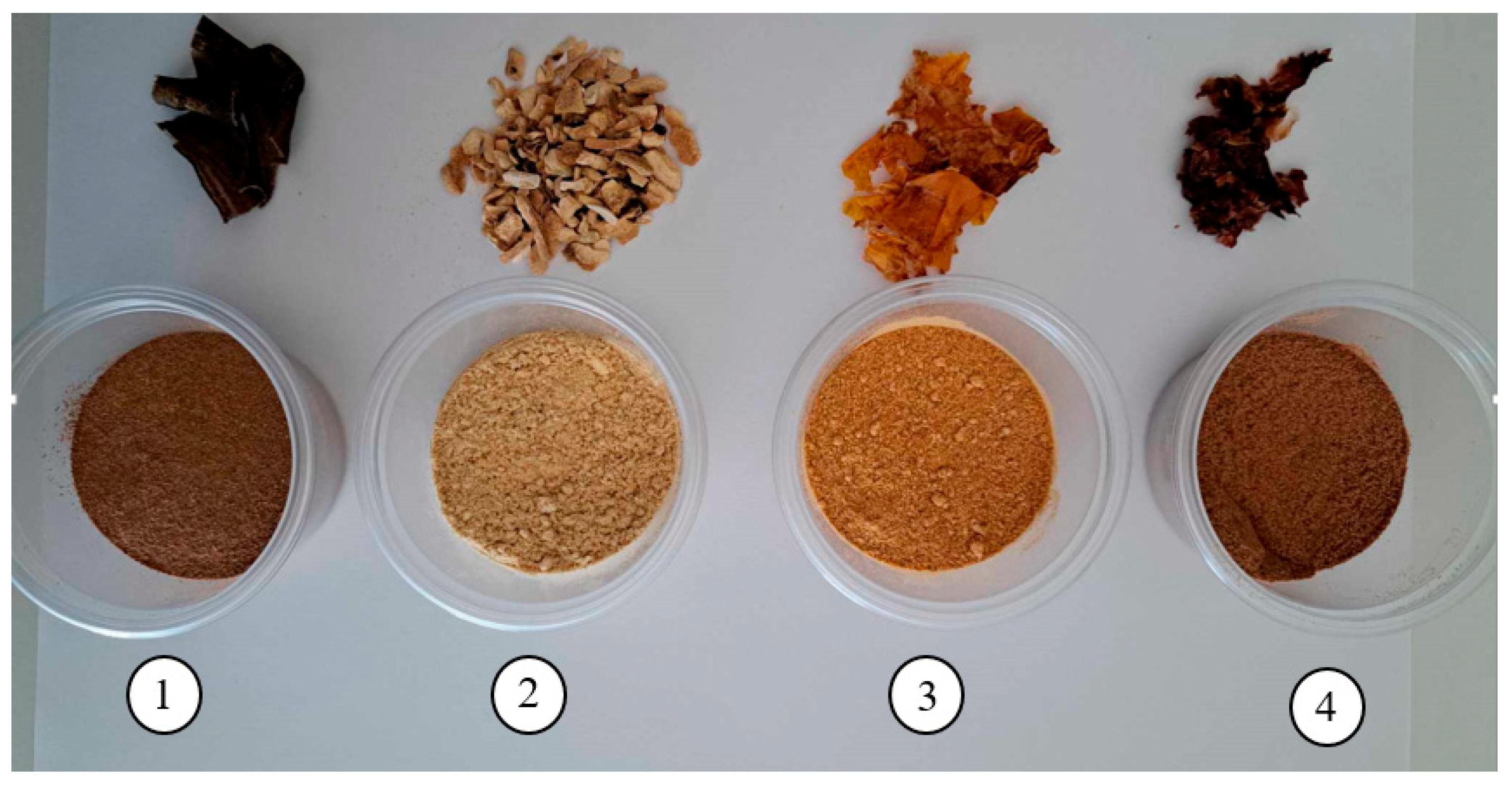

3.1. Research Material

3.2. Ultrasonic Extraction

3.3. Determination of the Concentration of Soluble Substances

3.4. Determination of Polyphenol Content in the Extracts

3.5. Carotenoid Content Determination

3.6. Vitamin C Content Determination

3.7. Production of Cleansing Gels

3.8. pH Analysis

3.9. Calculation of the Density of Each Gel

3.10. Turbidity Determination

3.11. Water Solubility Testing

3.12. Viscosity Testing

3.13. Foaming Capacity and Foam Stability Index Test

3.14. Measurement of Color Parameters

3.15. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kiewlicz, J.; Kwaśniewska, D. The influence of azelaic, succinic and gallic acids on the irritating potential of shower gels. In Current Trends in Quality Science; PTPN: Poznań, Poland, 2023; pp. 217–227. [Google Scholar]

- Morizet, D.; Aguiar, M.; Campion, J.-F.; Pessel, C.; De Lantivy, M.; Godard, C.; Dezeure, J. Water consumption by rinse-off cosmetic products: The case of the shower. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2023, 45, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sułek, M.W.; Janiszewska, J.; Kurzepa, K.; Mirkowska, B. Wpływ kompleksów anionowych surfaktantów z poliwinylopirolidonem tworzonych w roztworach wodnych na właściwości fizykochemiczne i użytkowe szamponów. Polimery 2018, 63, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Lamadrid, M.; Artés-Hernández, F. By-Products Revalorization with Non-Thermal Treatments to Enhance Phytochemical Compounds of Fruit and Vegetables Derived Products: A Review. Foods 2022, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauber, C.; Parente, E.; Zucca, M.P.; Gámbaro, A.; Vieitez, I. Olea europea and By-Products: Extraction Methods and Cosmetic Applications. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, E.; Carpentieri, S.; Pataro, G.; Ferrari, G. A Comprehensive Overview of Tomato Processing By-Product Valorization by Conventional Methods versus Emerging Technologies. Foods 2023, 12, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadvaja, N.; Gautam, S.; Singh, H. Natural polyphenols: A promising bioactive compounds for skin care and cosmetics. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 1817–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanyapanich, N.; Jimtaisong, A.; Rawdkuen, S. Functional Properties of Banana Starch (Musa spp.) and Its Utilization in Cosmetics. Molecules 2021, 26, 3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanninger, A.; Deckenhoff, V.; Goj, C.; Jackszis, L.; Pastewski, J.; Rajabi, S.; Rubbert, L.V.; Niederrhein, H.H. Upcycling of plant residuals to cosmetic ingredients. Int. J. Agric. Eng. Technol. Soc. Sci. 2022, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Vu, H.T.; Scarlett, C.J.; Vuong, Q.V. Phenolic compounds within banana peel and their potential uses: A review. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 40, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehiowemwenguan, G.; Emoghene, A.O.; Inetianbo, R.J.E. Antibacterial and phytochemical analysis of Banana fruit peel. J. Pharm. 2014, 4, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, G.K.; Singh, Y.; Mishra, S.P.; Rahangdale, H.K. Potential Use of Banana and Its By-products: A Review. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2018, 7, 1827–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavania, M.; Moryab, S.; Saxenaa, D.; Awuchi, C.G. Bioactive, antioxidant, industrial, and nutraceutical applications of banana peel. Int. J. Food Prop. 2023, 26, 1277–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabaraki, R.; Heidarizadi, E.; Benvidi, A. Optimization of ultrasonic-assisted extraction of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) peel antioxidants by response surface methodology. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2012, 98, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çam, M.; İçyer, N.C.; Erdoğan, F. Pomegranate peel phenolics: Microencapsulation, storage stability and potential ingredient for functional food development. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 55, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliarulo, C.; De Vito, V.; Picariello, G.; Colicchio, R.; Pastore, G.; Salvatore, P.; Volpe, M.G. Inhibitory effect of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) polyphenol extracts on the bacterial growth and survival of clinical isolates of pathogenic Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Food Chem. 2016, 190, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaderides, K.; Papaoikonomou, L.; Serafim, M.; Goula, A.M. Microwave-assisted extraction of phenolics from pomegranate peels: Optimization, kinetics, and comparison with ultrasounds extraction. Chem. Eng. Process.-Process. Intensif. 2019, 137, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Nanda, P.K.; Chowdhury, N.R.; Dandapat, P.; Gagaoua, M.; Chauhan, P.; Pateiro, M.; Lorenzo, J.M. Application of Pomegranate by-Products in Muscle Foods: Oxidative Indices, Colour Stability, Shelf Life and Health Benefits. Molecules 2021, 26, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam, M.N.; Lansky, E.P.; Varani, J. Pomegranate as a cosmeceutical source: Pomegranate fractions promote proliferation and procollagen synthesis and inhibit matrix metalloproteinase-1 production in human skin cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 103, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaid, M.A.; Afaq, F.; Syed, D.N.; Dreher, M.; Mukhtar, H. Inhibition of UVB-mediated oxidative stress and markers of photoaging in immortalized HaCaT keratinocytes by pomegranate polyphenol extract POMx. Photochem. Photobiol. 2007, 83, 882–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.M.; Moon, E.; Kim, A.J.; Kim, M.H.; Lee, S.; Lee, J.B.; Park, Y.K.; Jung, H.-S.; Kim, Y.B.; Kim, S.Y. Extract of Punica granatum inhibits skin photoaging induced by UVB irradiation. Int. J. Dermatol. 2010, 49, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, M.; Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Cui, Q. Pomegranate seeds: A comprehensive review of traditional uses, chemical composition, and pharmacological properties. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1401826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.-X.; Khyeam, S.; Zhang, Z.-J.; Zhang, K.Y.-B. Granatin B and Punicalagin from Chinese Herbal Medicine Pomegranate Peels Elicit Reactive Oxygen Species Mediated Apoptosis and Cell Cycle Arrest in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Phytomedicine 2022, 97, 153923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbulova, A.; Colucci, G.; Apone, F. New Trends in Cosmetics: By-Products of Plant Origin and Their Potential Use as Cosmetic Active Ingredients. Cosmetics 2015, 2, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, N.; Ferreira, I.C. Wastes and by-products: Upcoming sources of carotenoids for biotechnological purposes and health-related applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 62, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkowska, K.; Otlewska, A.; Raczyk, A.; Maciejczyk, E.; Krajewska, A. Valorisation of tomato pomace in anti-pollution and microbiome-balance face cream. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreassi, M.; Stanghellini, E.; Ettorre, A.; Di Stefano, A.; Andreassi, L. Antioxidant activity of topically applied lycopene. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2004, 18, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, L.B.; Van De Wall, H.; Li, H.T.; Venugopal, V.; Li, H.K.; Naydin, S.; Hosmer, J.; Levendusky, M.; Zheng, H.; Bentley, M.V.L.B.; et al. Topical delivery of lycopene using microemulsions: Enhanced skin penetration and tissue antioxidant activity. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 99, 1346–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasyliev, G.; Khrokalo, L.; Hladun, K.; Skiba, M.; Vorobyova, V. Valorization of tomato pomace: Extraction of value-added components by deep eutectic solvents and their application in the formulation of cosmetic emulsions. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2022, 12, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhlack, R.A.; Potumarthi, R.; Jeffery, D.W. Sustainable wineries through waste valorisation: A review of grape marc utilisation for value-added products. Waste Manage 2018, 72, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinei, M.; Oroian, M. The Potential of Grape Pomace Varieties as a Dietary Source of Pectic Substances. Foods 2021, 10, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.M.; Santos, L. A Potential Valorization Strategy of Wine Industry by-Products and Their Application in Cosmetics—Case Study: Grape Pomace and Grapeseed. Molecules 2022, 27, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, I.; Laneri, S. The New Challenge of Green Cosmetics: Natural Food Ingredients for Cosmetic Formulations. Molecules 2021, 26, 3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beres, C.; Costa, G.N.S.; Cabezudo, I.; da Silva-James, N.K.; Teles, A.S.C.; Cruz, A.P.G.; Mellinger-Silva, C.; Tonon, R.V.; Cabral, L.M.C.; Freitas, S.P. Towards integral utilization of grape pomace from winemaking process: A review. Waste Manag. 2017, 68, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoss, I.; Rajha, H.N.; El Khoury, R.; Youssef, S.; Manca, M.L.; Manconi, M.; Louka, N.; Maroun, R.G. Valorization of Wine-Making By-Products’ Extracts in Cosmetics. Cosmetics 2021, 8, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Park, K.Y.; Min, H.G.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, J.J.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, W.S.; Cha, H.J. Negative regulation of stress-induced matrix metalloproteinase-9 by Sirt1 in skin tissue. Exp. Dermatol. 2010, 19, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakka, A.K.; Babu, A.S. Bioactive Compounds of Winery By-Products: Extraction Techniques and Their Potential Health Benefits. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.; Barbosa, A.; Advinha, B.; Sales, H.; Pontes, R.; Nunes, J. Green Extraction Techniques of Bioactive Compounds: A State-of-the-Art Review. Processes 2023, 11, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirmal, N.P.; Khanashyam, A.C.; Mundanat, A.S.; Shah, K.; Babu, K.S.; Thorakkattu, P.; Al-Asmari, F.; Pandiselvam, R. Valorization of Fruit Waste for Bioactive Compounds and Their Applications in the Food Industry. Foods 2023, 12, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibade, A.; Batra, G.; Bozinou, E.; Salakidou, C.; Lalas, S. Optimization of the extraction of antioxidants from winery wastes using cloud point extraction and a surfactant of natural origin (lecithin). Chem. Pap. 2020, 74, 4517–4524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzimitakos, T.; Athanasiadis, V.; Mantiniotou, M.; Kalompatsios, D.; Bozinou, E.; Giovanoudis, I.; Lalas, S.I. Exploring the Feasibility of Cloud-Point Extraction for Bioactive Compound Recovery from Food Byproducts: A Review. Biomass 2023, 3, 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiszkiel, I.; Hryniewicka, M. Ekstrakcja micelarna jako alternatywna technika przygotowania próbek do analizy chemicznej. Bromatol. I Chem. Toksykol. 2011, 1, 104–116. [Google Scholar]

- Basri, M.S.M.; Shah, N.N.A.K.; Sulaiman, A.; Tawakkal, I.S.M.A.; Nor, M.Z.M.; Ariffin, S.H.; Ghani, N.H.A.; Salleh, F.S.M. Progress in the Valorization of Fruit and Vegetable Wastes: Active Packaging, Biocomposites, By-Products, and Innovative Technologies Used for Bioactive Compound Extraction. Polymers 2021, 13, 3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, B.G.; Mukhtar, K.; Ansar, S.; Hassan, S.A.; Hafeez, M.A.; Bhat, Z.F.; Khaneghah, A.M.; Ul Haq, A.; Aadil, R.M. Application of ultrasound technology for the effective management of waste from fruit and vegetable. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024, 102, 106744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasilewski, T.; Hordyjewicz-Baran, Z.; Zarębska, M.; Stanek, N.; Zajszły-Turko, E.; Tomaka, M.; Bujak, T.; Nizioł-Łukaszewska, Z. Sustainable Green Processing of Grape Pomace Using Micellar Extraction for the Production of Value-Added Hygiene Cosmetics. Molecules 2022, 27, 2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasilewski, T.; Hordyjewicz-Baran, Z.; Malorna, K.; Dresler, E.; Sabura, E.; Zegarski, M.; Stanek-Wandzel, N. Studies on the Use of Loan Extraction to Produce Natural Shower Gels (Cosmetic) Based on Grape Pomace Extracts—The Effect of the Type of Surfactant Borrowed. Molecules 2025, 30, 3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hordyjewicz-Baran, Z.; Wasilewski, T.; Zarębska, M.; Stanek-Wandzel, N.; Zajszły-Turko, E.; Tomaka, M.; Zagórska-Dziok, M. Micellar and Solvent Loan Chemical Extraction as a Tool for the Development of Natural Skin Care Cosmetics Containing Substances Isolated from Grapevine Buds. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenzato, A.; Costantini, A.; Baratto, G. Green Polymers in Personal Care Products: Rheological Properties of Tamarind Seed Polysaccharide. Cosmetics 2015, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsena, Y.P.; Phosanam, A.; Stockmann, R. Perspectives on Saponins: Food Functionality and Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, M.S.; Romero-Díez, R.; Álvarez, A.; Bronze, M.R.; Rodríguez-Rojo, S.; Mato, R.B.; Cocero, M.J.; Matias, A.A. Polyphenol-Rich Extracts Obtained from Winemaking Waste Streams as Natural Ingredients with Cosmeceutical Potential. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarovaya, L.; Khunkitti, W. The Effect of Grape Seed Extract as a Sunscreen Booster. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 2019, 4, 708–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, K.; Cătoi, A.F.; Vodnar, D.C. Bioactive Compounds Extracted from Tomato Processing by-Products as a Source of Valuable Nutrients. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2018, 73, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamaleddine, A.; Urrutigoïty, M.; Bouajila, J.; Merah, O.; Evon, P.; de Caro, P. Ecodesigned Formulations with Tomato Pomace Extracts. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opara, L.U.; Al-Ani, M.R.; Al-Shuaibi, Y.S. Physico-chemical Properties, Vitamin C Content, and Antimicrobial Properties of Pomegranate Fruit (Punica granatum L.). Food Bioprocess Technol. 2009, 2, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, E.C.; Uchôa-Thomaz, A.M.A.; Carioca, J.O.B.; Morais, S.M.D.; Lima, A.D.; Martins, C.G.; Alexandrino, C.D.; Ferreira, P.A.T.; Rodrigues, A.L.M.; Rodrigues, S.P.; et al. Chemical composition and bioactive compounds of grape pomace (Vitis vinifera L.), Benitaka variety, grown in the semiarid region of Northeast Brazil. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 34, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanță, L.C.; Fărcaş, A.C. Exploring the efficacy and feasibility of tomato by-products in advancing food industry applications. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, K.M.; Dhanya, M. Unlocking the potential of banana peel bioactives: Extraction methods, benefits, and industrial applications. Discov. Food 2025, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boo, Y.C. Ascorbic Acid (Vitamin C) as a Cosmeceutical to Increase Dermal Collagen for Skin Antiaging Purposes: Emerging Combination Therapies. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalik, P.; Szyrej, M. The study of the selected properties of shower gels and bubble baths depending on a kind of a used surfactants. Chem. Environ. Biotechnol. 2016, 19, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, E.; Bordegoni, M.; Spence, C. Investigating the influence of colour, weight, and fragrance intensity on the perception of liquid bath soap: An experimental study. Food Qual. Pref. 2014, 31, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzdrowska, K. Recepturowanie Kosmetyków i Proces ich Wdrożenia; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.; Kim, S.; Nam, G.W.; Lee, H.; Moon, S.; Chang, I. The alkaline pH-adapted skin barrier is disrupted severely by SLS-induced irritation. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2009, 31, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, K.A.; Roberts, J.S. Microwave heating of apple mash to improve juice yield and quality. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2004, 37, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojdyło, A.; Teleszko, M.; Oszmiański, J. Physicochemical characterisation of quince fruits for industrial use: Yield, turbidity, viscosity and colour properties of juices. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 49, 1818–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyedoh, E.A.; Balogun, G.D.; Atapia, M.I.; Ossai, J.E.; Joseph, E.S. Optimization of Saponin-Based Biosurfactants from Banana and Lemon Peels. J. App. Sci. Environ. Manage 2025, 29, 1633–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zięba, M.; Ruszkowska, M.; Klepacka, J. From Forest Berry Leaf Waste to Micellar Extracts with Cosmetic Applications. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zięba, M.; Klimaszewska, E.; Ogorzałek, M.; Ruszkowska, M. The Role of Burdock and Black Radish Powders Obtained by Low-Temperature Drying in Emulsion-Type Hair Conditioners. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogorzałek, M.; Klimaszewska, E.; Małysa, A.; Czerwonka, D.; Tomasiuk, R. Research on Waterless Cosmetics in the Form of Scrub Bars Based on Natural Exfoliants. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewska, M.; Starek-Wójcicka, A.; Sagan, A.; Sachadyn-Król, M.; Osmólska, E. Effect of Lyophilised Sumac Extract on the Microbiological, Physicochemical, and Antioxidant Properties of Fresh Carrot Juice. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-ISO 696; Surfactants. Determination of Foamability by Ross-Miles Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1994.

| Probe | SSC (°Brix) | TPC (mg·100 mL−1) | TCC (mg·mL−1) | Vitamin C (mg·100 mL−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPE | 2.30 ± 0.00 b | 16.54 ± 0.03 a | 1.831 ± 0.085 b | 0.651 ± 0.056 c |

| PPE | 2.47 ± 0.06 a | 16.52 ± 0.04 a | 1.391 ± 0.049 c | 1.529 ± 0.056 a |

| TPE | 2.13 ± 0.06 c | 10.99 ± 0.04 c | 2.402 ± 0.028 a | 1.139 ± 0.056 b |

| GPE | 2.33 ± 0.06 b | 13.44 ± 0.05 b | 1.831 ± 0.085 b | 1.236 ± 0.113 b |

| Probe | Solubility (min) | Viscosity (mPa) | Density (g·cm−3) | pH (-) | Turbidity (NTU) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG | 39.0 ± 2.6 a | 402.9 ± 2.9 b | 0.856 ± 0.004 c | 5.917 ± 0.002 a | 8.98 ± 0.07 c |

| BPG | 27.7 ± 1.5 b | 412.1 ± 5.0 ab | 0.735 ± 0.005 d | 5.594 ± 0.003 d | 11.47 ± 0.23 ab |

| PPG | 15.7 ± 1.5 c | 303.4 ± 3.1 d | 0.974 ± 0.010 b | 5.786 ± 0.021 b | 10.67 ± 0.15 b |

| TPG | 29.0 ± 1.0 b | 358.8 ± 7.6 c | 0.996 ± 0.002 a | 5.391 ± 0.005 e | 12.23 ± 0.40 a |

| GPG | 29.7 ± 0.6 b | 416.8 ± 4.0 a | 0.999 ± 0.001 a | 5.723 ± 0.009 c | 10.80 ± 0.50 b |

| Probe | L* | a* | b* | ΔE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG | 52.81 ± 0.52 a | −0.89 ± 0.03 e | 1.71 ± 0.13 d | 0 |

| BPG | 46.31 ± 0.32 b | 1.46 ± 0.08 a | 15.03 ± 0.41 a | 15.01 |

| PPG | 32.27 ± 0.25 e | −0.61 ± 0.03 d | 3.89 ± 0.07 c | 20.65 |

| TPG | 34.88 ± 1.20 d | 1.20 ± 0.20 b | 9.36 ± 1.03 b | 19.61 |

| GPG | 38.40 ± 0.83 c | −0.40 ± 0.05 c | 3.43 ± 0.16 c | 14.52 |

| Ingredients (g) | By-Product Extract | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CE | BPE | PPE | TPE | GPE | |

| Distilled water | 185 | 185 | 185 | 185 | 185 |

| Decyl Glucoside | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| DHA-BA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Dry by-products | - | Banana peel | Pomegranate peel | Tomato pomace | Grape pomace |

| 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | ||

| Ingredients (%) | Control Extract | Banana Peel Extract | Pomegranate Peel Extract | Tomato Pomace Extract | Grape Pomace Extract | DHA BA | SCI | Coconut Betaine | Sodium Chloride | Distilled Water | Decyl Glucoside | Xanthan Gum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG | 65 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.5 | 2 | 1 | Up to 100 | 4 | 1.4 |

| BPG | 0 | 65 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.5 | 2 | 1 | Up to 100 | 4 | 1.4 |

| PPG | 0 | 0 | 65 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.5 | 2 | 1 | Up to 100 | 4 | 1.4 |

| TPG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 65 | 0 | 1 | 4.5 | 2 | 1 | Up to 100 | 4 | 1.4 |

| GPG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 65 | 1 | 4.5 | 2 | 1 | Up to 100 | 4 | 1.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blicharz-Kania, A.; Iwanek, M.; Pecyna, A. Extracts from By-Products of the Fruit and Vegetable Industry as Ingredients Improving the Properties of Cleansing Gels. Molecules 2025, 30, 4687. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244687

Blicharz-Kania A, Iwanek M, Pecyna A. Extracts from By-Products of the Fruit and Vegetable Industry as Ingredients Improving the Properties of Cleansing Gels. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4687. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244687

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlicharz-Kania, Agata, Magdalena Iwanek, and Anna Pecyna. 2025. "Extracts from By-Products of the Fruit and Vegetable Industry as Ingredients Improving the Properties of Cleansing Gels" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4687. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244687

APA StyleBlicharz-Kania, A., Iwanek, M., & Pecyna, A. (2025). Extracts from By-Products of the Fruit and Vegetable Industry as Ingredients Improving the Properties of Cleansing Gels. Molecules, 30(24), 4687. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244687