Can Aquatic Plant Turions Serve as a Source of Arabinogalactans? Immunohistochemical Detection of AGPs in Turion Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

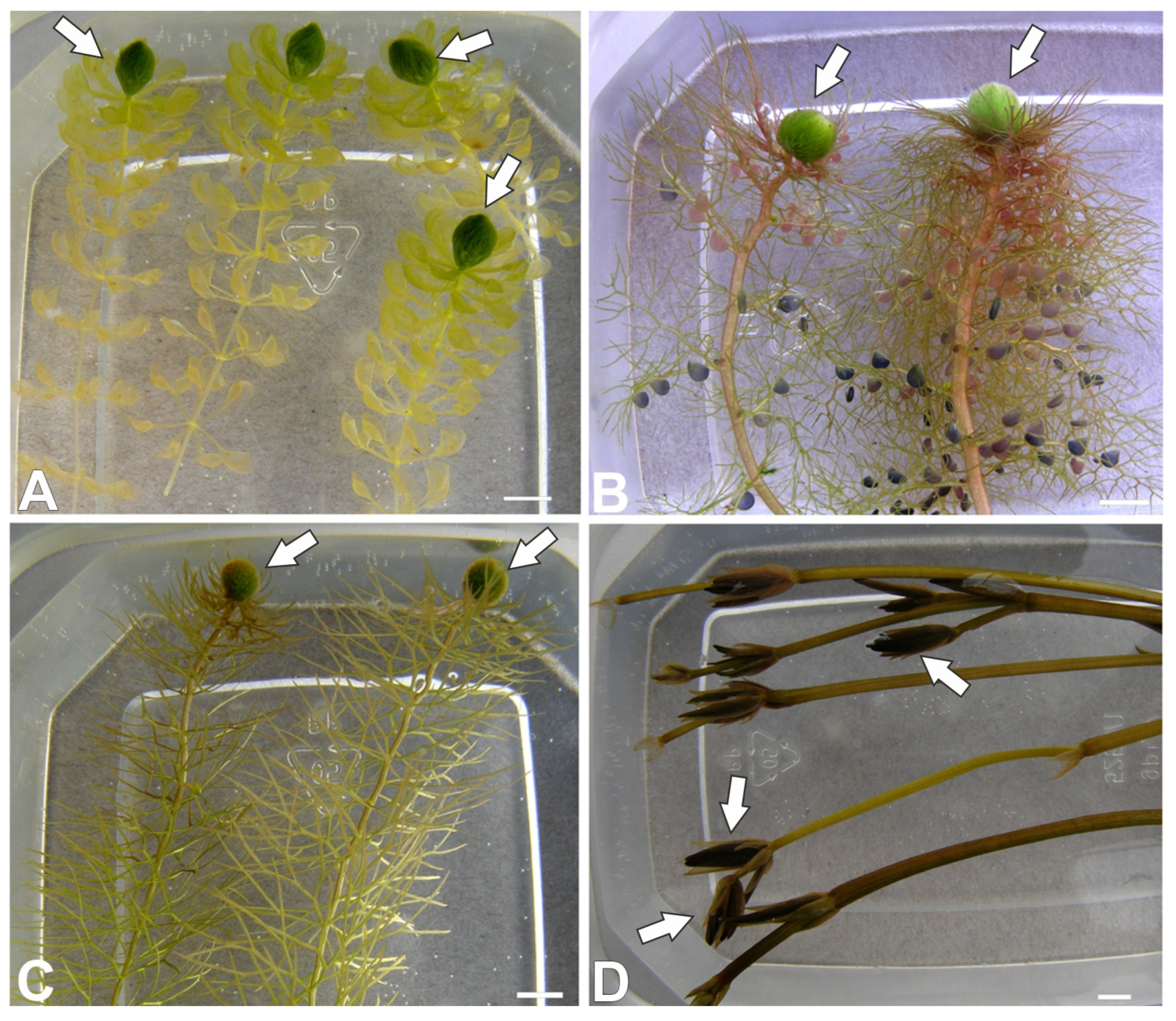

2.1. Characterization of Turions in Aquatic Plants

2.2. AGP Detection in Aldrovanda vesiculosa

2.3. AGP Detection in Utricularia australis and U. intermedia

2.4. AGP Detection in Caldesia parnassifolia

2.5. Summary

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Sample Collection

4.2. Immunolocalization of AGPs

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sculthorpe, C.D. The Biology of Aquatic Vascular Plants; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, R. Das Austreiben der Turionen von Utricularia vulgaris L. nach verschiedenen langen Perioden der Austrocknung. Flora 1973, 162, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, R. Wirkung von Trockenheit auf den Austrieb der Turionen von Utricularia L. Österr. Bot. Z. 1973, 122, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winston, R.D.; Gorham, P.R. Turions and dormancy states in Utricularia vulgaris. Can. J. Bot. 1979, 57, 2740–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamec, L. Ecophysiological characteristics of turions of aquatic plants: A review. Aquat. Bot. 2018, 148, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, P. The Developmental Cycle of Spirodela polyrhiza Turions: A Model for Turion-Based Duckweed Overwintering? Plants 2024, 13, 2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figuerola, J.; Green, A.J. Dispersal of aquatic organisms by waterbirds: A review of past research and priorities for future studies. Freshw. Biol. 2002, 47, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.J.; Lovas-Kiss, Á.; Reynolds, C.; Sebastián-González, E.; Silva, G.G.; van Leeuwen, C.H.; Wilkinson, D.M. Dispersal of aquatic and terrestrial organisms by waterbirds: A review of current knowledge and future priorities. Freshw. Biol. 2023, 68, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamec, L. Dark respiration and photosynthesis of dormant and sprouting turions of aquatic plants. Fundam. Appl. Limnol. 2011, 179, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimann, R.; Hippler, M.; Machelett, B.; Appenroth, K.-J. Light induces phosphorylation of glucan water dikinase, which precedes starch degradation in turions of the duckweed Spirodela polyrhiza. Plant Physiol. 2004, 135, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appenroth, K.-J.; Ziegler, P. Light-induced degradation of storage starch in turions of Spirodela polyrhiza depends on nitrate. Plant Cell Environ. 2008, 31, 1460–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appenroth, K.J.; Keresztes, Á.; Krzysztofowicz, E.; Gabrys, H. Light-induced degradation of starch granules in turions of Spirodela polyrhiza studied by electron microscopy. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011, 52, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Płachno, B.J.; Adamec, L.; Kozieradzka-Kiszkurno, M.; Świątek, P.; Kamińska, I. Cytochemical and ultrastructural aspects of aquatic carnivorous plant turions. Protoplasma 2014, 251, 1449–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamec, L.; Kučerová, A.; Janeček, Š. Mineral nutrients, photosynthetic pigments and storage carbohydrates in turions of 21 aquatic plant species. Aquat. Bot. 2020, 165, 103238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, T.; Ishizawa, K. Starch degradation and sucrose metabolism during anaerobic growth of pondweed (Potamogeton distinctus A. Benn.) turions. Plant Soil 2003, 253, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamec, L. Respiration of turions and winter apices in aquatic carnivorous plants. Biologia 2008, 63, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.A.; Nooden, L.D. The causes of sinking and floating in turions of Myriophyllum verticillatum. Aquat. Bot. 2005, 83, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.L.; Fang, Y.; Li, Q.; Yang, G.L.; Guo, L.; Chen, G.K.; Tan, L.; He, K.-Z.; Jin, Y.-L.; Zhao, H. Turion, an innovative duckweed-based starch production system for economical biofuel manufacture. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 124, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, V.R.; Simola, L.K.; Mardon, M. Polyamines in turions and young plants of Hydrocharis morsus-ranae and Utricularia intermedia. Phytochemistry 1985, 24, 171–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzemski, M.; Adamec, L.; Dresler, S.; Mazurek, B.; Dubaj, K.; Stolarczyk, P.; Feldo, M.; Płachno, B.J. Shoots and Turions of Aquatic Plants as a Source of Fatty Acids. Molecules 2024, 29, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genevès, L.; Vintejoux, C. Sur la présence et l’organisation en un réseau tridimensionnel d’inclusions de nature protéique dans les noyaux cellulaires des hibernacles, d’Utricularia neglecta L. (Lentibulariacées). C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris D 1967, 264, 2750–2753. [Google Scholar]

- Vintejoux, C. Inclusions intranucléaires d’Utricularia neglecta L. (Lentibulariacées). Ann. Sci. Nat. Bot. 1984, 6, 203–205. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J.; Ferraz, R.; Dupree, P.; Showalter, A.M.; Coimbra, S. Three decades of advances in arabinogalactan-protein biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 610377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Showalter, A.M. Arabinogalactan-proteins: Structure, expression and function. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2001, 58, 1399–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifert, G.J.; Roberts, K. The biology of arabinogalactan proteins. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2007, 58, 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showalter, A.M.; Basu, D. Extensin and arabinogalactan-protein biosynthesis: Glycosyltransferases, research challenges, and biosensors. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willats, W.G.; Knox, J.P. A role for arabinogalactan-proteins in plant cell expansion: Evidence from studies on the interaction of β-glucosyl Yariv reagent with seedlings of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1996, 9, 919–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, M.; Egelund, J.; Schultz, C.J.; Bacic, A. Arabinogalactan-proteins: Key regulators at the cell surface? Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.M.; Pereira, L.G.; Coimbra, S. Arabinogalactan proteins: Rising attention from plant biologists. Plant Reprod. 2015, 28, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamport, D.T.A.; Tan, L.; Held, M.; Kieliszewski, M.J. Pollen tube growth and guidance: Occam’s razor sharpened on a molecular arabinogalactan glycoprotein Rosetta Stone. New Phytol. 2018, 217, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Johnson, K. Arabinogalactan proteins—Multifunctional glycoproteins of the plant cell wall. Cell Surf. 2023, 9, 100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, A.Y.; Wu, H.M. Arabinogalactan proteins in plant sexual reproduction. Protoplasma 1999, 208, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coimbra, S.; Almeida, J.; Junqueira, V.; Costa, M.L.; Pereira, L.G. Arabinogalactan proteins as molecular markers in Arabidopsis thaliana sexual reproduction. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 4027–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leszczuk, A.; Szczuka, E.; Zdunek, A. Arabinogalactan proteins: Distribution during the development of male and female gametophytes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 135, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, A.L.; Moreira, D.; Pereira, A.M.; Ferraz, R.; Mendes, S.; Pereira, L.G.; Colombo, L.; Coimbra, S. AGPs as molecular determinants of reproductive development. Ann. Bot. 2023, 131, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, J.; Moreira, D.; Ferreira, M.J.; Pereira, A.M.; Pereira, L.G.; Coimbra, S. Arabinogalactan proteins: Decoding the multifaceted roles in plant reproduction. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2025, 88, 102800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapusta, M.; Narajczyk, M.; Płachno, B.J. Arabinogalactan Proteins Mark the Generative Cell–Vegetative Cell Interface in Monocotyledonous Pollen Grains. Cells 2025, 14, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Song, J.; Lv, X.; Wang, Z.; Huang, L.; Du, Y. Structural characterization of an arabinogalactan-protein from the fruits of Lycium ruthenicum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 9424–9429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczuk, A.; Chylińska, M.; Zięba, E.; Skrzypek, T.; Szczuka, E.; Zdunek, A. Structural network of arabinogalactan proteins (AGPs) and pectins in apple fruit during ripening and senescence processes. Plant Sci. 2018, 275, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsumuraya, Y.; Ozeki, E.; Ooki, Y.; Yoshimi, Y.; Hashizume, K.; Kotake, T. Properties of arabinogalactan-proteins in European pear (Pyrus communis L.) fruits. Carbohydr. Res. 2019, 485, 107816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczuk, A.; Kalaitzis, P.; Blazakis, K.N.; Zdunek, A. The role of arabinogalactan proteins (AGPs) in fruit ripening—A review. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, S.; Powers, S.; Monteagudo-Mera, A.; Kosik, O.; Lovegrove, A.; Shewry, P.; Charalampopoulos, D. Determination of the prebiotic activity of wheat arabinogalactan peptide (AGP) using batch culture fermentation. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeidy, S.; Petera, B.; Pierre, G.; Fenoradosoa, T.A.; Djomdi, D.; Michaud, P.; Delattre, C. Plants arabinogalactans: From structures to physicochemical and biological properties. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 53, 107771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Shi, S.; Bao, B.; Li, X.; Wang, S. Structure characterization of an arabinogalactan from green tea and its anti-diabetic effect. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 124, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Wang, T.; Huang, C.; Lai, C.; Fan, Y.; Yong, Q. Sulfated modification of arabinogalactans from Larix principis-rupprechtii and their antitumor activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 215, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, L.; Cao, S.; Luo, K.; Zhang, J.; Dinnyés, A.; Wang, D.; Sun, Q. A novel arabinogalactan extracted from Epiphyllum oxypetalum (DC.) Haw improves the immunity and gut microbiota in cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppressed mice. eFood 2024, 5, e70002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, K.Y.; Ding, W.J.; Li, Z.T.; Liu, C.; Ji, H.Y.; Liu, A.J. Comparison of structural characteristics and antitumor activity of two alkali-extracted peach gum arabinogalactans. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Xu, T.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Ruan, M.; Xu, H.; Chen, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; et al. Arabinogalactan from Cynanchum atratum induces tolerogenic dendritic cells in gut to restrain autoimmune response and alleviate collagen-induced arthritis in mice. Phytomedicine 2025, 136, 156269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Persson, S.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, C. At the Border: The Plasma Membrane–Cell Wall Continuum. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 1553–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.K.C.; Lee, S.J. Straying off the Highway: Trafficking of Secreted Plant Proteins and Complexity in the Plant Cell Wall Proteome. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijazi, M.; Velasquez, S.M.; Jamet, E.; Estevez, J.M.; Albenne, C. An Update on Post-Translational Modifications of Hydroxyproline-Rich Glycoproteins: Toward a Model Highlighting Their Contribution to Plant Cell Wall Architecture. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nibbering, P.; Petersen, B.L.; Motawia, M.S.; Jørgensen, B.; Ulvskov, P.; Niittylä, T. Golgi-Localized Exo-β1,3-Galactosidases Involved in Cell Expansion and Root Growth in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 10581–10592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawecki, R.; Sala, K.; Kurczyńska, E.U.; Świątek, P.; Płachno, B.J. Immunodetection of some pectic, arabinogalactan proteins and hemicellulose epitopes in the micropylar transmitting tissue of apomictic dandelions (Taraxacum, Asteraceae, Lactuceae). Protoplasma 2017, 254, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potocka, I.; Godel, K.; Dobrowolska, I.; Kurczyńska, E.U. Spatio-temporal localization of selected pectic and arabinogalactan protein epitopes and the ultrastructural characteristics of explant cells that accompany the changes in the cell fate during somatic embryogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 127, 573–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šamaj, J.; Šamajová, O.; Peters, M.; Baluška, F.; Lichtscheidl, I.; Knox, J.P.; Volkmann, D. Immunolocalization of LM2 Arabinogalactan Protein Epitope Associated with Endomembranes of Plant Cells. Protoplasma 2000, 212, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczuk, A.; Szczuka, E. Arabinogalactan Proteins: Immunolocalization in the Developing Ovary of a Facultative Apomict Fragaria × ananassa (Duch.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 123, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczuk, A.; Wydrych, J.; Szczuka, E. The Occurrence of Calcium Oxalate Crystals and Distribution of Arabinogalactan Proteins (AGPs) in Ovary Cells during Fragaria × ananassa (Duch.) Development. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2019, 38, 1028–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płachno, B.J.; Kapusta, M.; Świątek, P.; Stolarczyk, P.; Kocki, J. Immunodetection of Pectic Epitopes, Arabinogalactan Proteins, and Extensins in Mucilage Cells from the Ovules of Pilosella officinarum Vaill. and Taraxacum officinale Agg. (Asteraceae). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Pereira, A.M.; Rudall, P.J.; Coimbra, S. Immunolocalization of Arabinogalactan Proteins (AGPs) in Reproductive Structures of an Early-Divergent Angiosperm, Trithuria (Hydatellaceae). Ann. Bot. 2013, 111, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płachno, B.J.; Adamec, L.; Świątek, P.; Kapusta, M.; Miranda, V.F.O. Life in the Current: Anatomy and Morphology of Utricularia neottioides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płachno, B.J.; Kapusta, M.; Stolarczyk, P.; Feldo, M.; Świątek, P. Cell Wall Microdomains in the External Glands of Utricularia dichotoma Traps. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płachno, B.J.; Kapusta, M.; Stolarczyk, P.; Feldo, M.; Świątek, P. Do Arabinogalactan Proteins Occur in the Transfer Cells of Utricularia dichotoma? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płachno, B.J.; Kapusta, M.; Stolarczyk, P.; Wójciak, M.; Świątek, P. Immunocytochemical Analysis of Bifid Trichomes in Aldrovanda vesiculosa L. Traps. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Płachno, B.J.; Kapusta, M.; Stolarczyk, P.; Świątek, P.; Lichtscheidl, I. Differences in the Occurrence of Cell Wall Components between Distinct Cell Types in Glands of Drosophyllum lusitanicum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Płachno, B.J.; Kapusta, M.; Stolarczyk, P.; Świątek, P. Stellate Trichomes in Dionaea muscipula Ellis (Venus Flytrap) Traps: Structure and Functions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Płachno, B.J.; Kapusta, M.; Stolarczyk, P.; Feldo, M.; Świątek, P.; Miranda, V.F.O. Immunocytochemical Analysis of the Wall Ingrowths in the Digestive Gland Transfer Cells in Aldrovanda vesiculosa L. (Droseraceae). Cells 2022, 11, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płachno, B.J.; Kapusta, M.; Stolarczyk, P.; Świątek, P. Arabinogalactan Proteins in the Digestive Glands of Dionaea muscipula J. Ellis Traps. Cells 2022, 11, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCurdy, D.W.; Patrick, J.W.; Offler, C.E. Wall Ingrowth Formation in Transfer Cells: Novel Examples of Localized Wall Deposition in Plant Cells. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2008, 11, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweingruber, F.H.; Kučerová, A.; Adamec, L.; Doležal, J. Anatomic Atlas of Aquatic and Wetland Plant Stems; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Leme, F.M.; Bento, J.P.S.P.; Fabiano, V.S.; González, J.D.V.; Pott, V.J.; Arruda, R.D.C.O. New Aspects of Secretory Structures in Five Alismataceae Species: Laticifers or Ducts? Plants 2021, 10, 2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michavila, S.; Encina, A.; De la Rubia, A.G.; Centeno, M.L.; García-Angulo, P. An Immunohistochemical Approach to Cell Wall Polysaccharide Specialization in Maritime Pine (Pinus pinaster) Needles. Protoplasma 2025, 262, 979–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastroberti, A.A.; Mariath, J.E.D.A. Immunocytochemistry of the Mucilage Cells of Araucaria angustifolia (Bertol.) Kuntze (Araucariaceae). Braz. J. Bot. 2008, 31, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haughn, G.W.; Western, T.L. Arabidopsis Seed Coat Mucilage Is a Specialized Cell Wall That Can Be Used as a Model for Genetic Analysis of Plant Cell Wall Structure and Function. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, O.O.; Held, M.A.; Showalter, A.M. Two β-Glucuronosyltransferases Involved in the Biosynthesis of Type II Arabinogalactans Function in Mucilage Polysaccharide Matrix Organization in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzec-Schmidt, K.; Ludwikow, A.; Wojciechowska, N.; Kasprowicz-Maluski, A.; Mucha, J.; Bagniewska-Zadworna, A. Xylem Cell Wall Formation in Pioneer Roots and Stems of Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray). Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalak, K.M.; Wojciechowska, N.; Marzec-Schmidt, K.; Bagniewska-Zadworna, A. Conserved Autophagy and Diverse Cell Wall Composition: Unifying Features of Vascular Tissues in Evolutionarily Distinct Plants. Ann. Bot. 2024, 133, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzec, M.; Szarejko, I.; Melzer, M. Arabinogalactan Proteins Are Involved in Root Hair Development in Barley. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 1245–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalak, K.M.; Wojciechowska, N.; Kułak, K.; Minicka, J.; Jagodziński, A.M.; Bagniewska-Zadworna, A. Is Autophagy Always a Death Sentence? A Case Study of Highly Selective Cytoplasmic Degradation during Phloemogenesis. Ann. Bot. 2025, 135, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defaye, J.; Wong, E. Structural Studies of Gum Arabic, the Exudate Polysaccharide from Acacia senegal. Carbohydr. Res. 1986, 150, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Torrez, L.; Nigen, M.; Williams, P.; Doco, T.; Sanchez, C. Acacia senegal vs. Acacia seyal Gums—Part 1: Composition and Structure of Hyperbranched Plant Exudates. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 51, 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bouaziz, F.; Koubaa, M.; Ghorbel, R.E.; Chaabouni, S.E. Recent Advances in Rosaceae Gum Exudates: From Synthesis to Food and Non-Food Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 86, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babkin, V.A.; Neverova, N.A.; Medvedeva, E.N.; Fedorova, T.E.; Levchuk, A.A. Investigation of Physicochemical Properties of Arabinogalactan of Different Larch Species. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2016, 42, 707–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parzymies, M.; Pogorzelec, M.; Świstowska, A. Optimization of Propagation of the Polish Strain of Aldrovanda vesiculosa in Tissue Culture. Biology 2022, 11, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójciak, M.; Sowa, I.; Strzemski, M.; Parzymies, M.; Pogorzelec, M.; Stolarczyk, P.; Płachno, B.J. Phenolic Secondary Metabolites in Aldrovanda vesiculosa L. (Droseraceae). Molecules 2025, 30, 3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knox, J.P.; Linstead, P.J.; Peart, J.; Cooper, C.; Roberts, K. Developmentally Regulated Epitopes of Cell Surface Arabinogalactan Proteins and Their Relation to Root Tissue Pattern Formation. Plant J. 1991, 1, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, E.A.; Valdor, J.F.; Haslam, S.M.; Morris, H.R.; Dell, A.; Mackie, W.; Knox, J.P. Characterization of Carbohydrate Structural Features Recognized by Anti-Arabinogalactan-Protein Monoclonal Antibodies. Glycobiology 1996, 6, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, M.; Yates, E.A.; Willats, W.G.T.; Martin, H.; Knox, J.P. Immunochemical Comparison of Membrane-Associated and Secreted Arabinogalactan Proteins in Rice and Carrot. Planta 1996, 198, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antibody | JIM8 | JIM13 | JIM14 | LM2 | MAC207 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | ||||||

| Aldrovanda vesiculosa | Epidermal cells, glands, parenchyma cells, vascular tissues showed epitopes associated with cell walls and also with intracellular compartments | Epidermal cells, glands, parenchyma cells, vascular tissues showed epitopes associated with cell walls and also with intracellular compartments | Epidermal cells, parenchymal cells, basal cells of glands, vascular tissues showed epitopes associated with the wall/plasma membrane | Parenchymal cells, vascular tissue showed epitopes associated with intracellular compartments | Was not found | |

| Utricularia australis | Mainly glandular trichomes and vascular bundle cells | Mainly glandular trichomes | Mainly glandular trichomes | Epidermal cells | Was not found | |

| Utricularia intermedia | Mainly glandular trichomes | Mainly glandular trichomes, epidermal cells, parenchymal cells | Mainly glandular trichomes, with a weak dotted signal in epidermal cells | Epidermal cells | Was not found | |

| Caldesia parnassifolia | Epidermal and parenchyma cells, vascular tissue. Intensive signal in secretory duct cells; epitopes were abundantly present in the cytoplasmic compartments | Parenchyma cells, vascular tissue, secretory duct cells in the cytoplasmic compartments | Mainly present in vascular bundle cells Cell walls, cytoplasmic compartments of various cells | Abundant in epidermal outgrowths, present in epidermal cells and cytoplasmic compartments of various cells | Xylem elements and canals | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Płachno, B.J.; Adamec, L.; Feldo, M.; Stolarczyk, P.; Kapusta, M. Can Aquatic Plant Turions Serve as a Source of Arabinogalactans? Immunohistochemical Detection of AGPs in Turion Cells. Molecules 2025, 30, 4689. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244689

Płachno BJ, Adamec L, Feldo M, Stolarczyk P, Kapusta M. Can Aquatic Plant Turions Serve as a Source of Arabinogalactans? Immunohistochemical Detection of AGPs in Turion Cells. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4689. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244689

Chicago/Turabian StylePłachno, Bartosz J., Lubomír Adamec, Marcin Feldo, Piotr Stolarczyk, and Małgorzata Kapusta. 2025. "Can Aquatic Plant Turions Serve as a Source of Arabinogalactans? Immunohistochemical Detection of AGPs in Turion Cells" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4689. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244689

APA StylePłachno, B. J., Adamec, L., Feldo, M., Stolarczyk, P., & Kapusta, M. (2025). Can Aquatic Plant Turions Serve as a Source of Arabinogalactans? Immunohistochemical Detection of AGPs in Turion Cells. Molecules, 30(24), 4689. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244689