Chemical Composition and In Vitro Antidiabetic Effect of Extracts from Ripe, Unripe, and Fermented Unripe Cornus mas L. Fruits

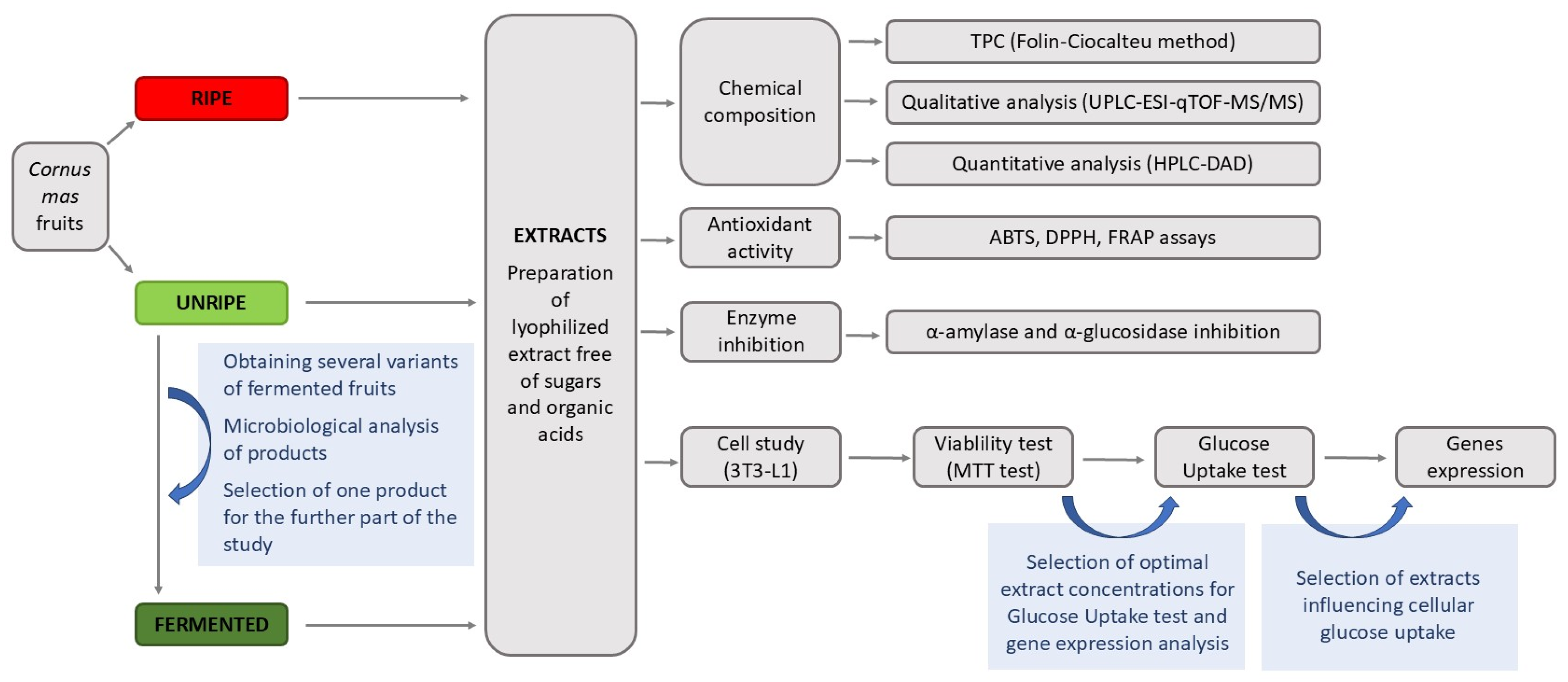

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Fermentation of Unripe Cornelian Cherry Fruits

2.2. Identification of Phenolic Compounds and Iridoids in C. mas Extracts

2.3. Quantification of Phenolic Compounds and Iridoids in C. mas Extracts

2.4. Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity of C. mas Extracts

2.5. α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity of the C. mas Extracts

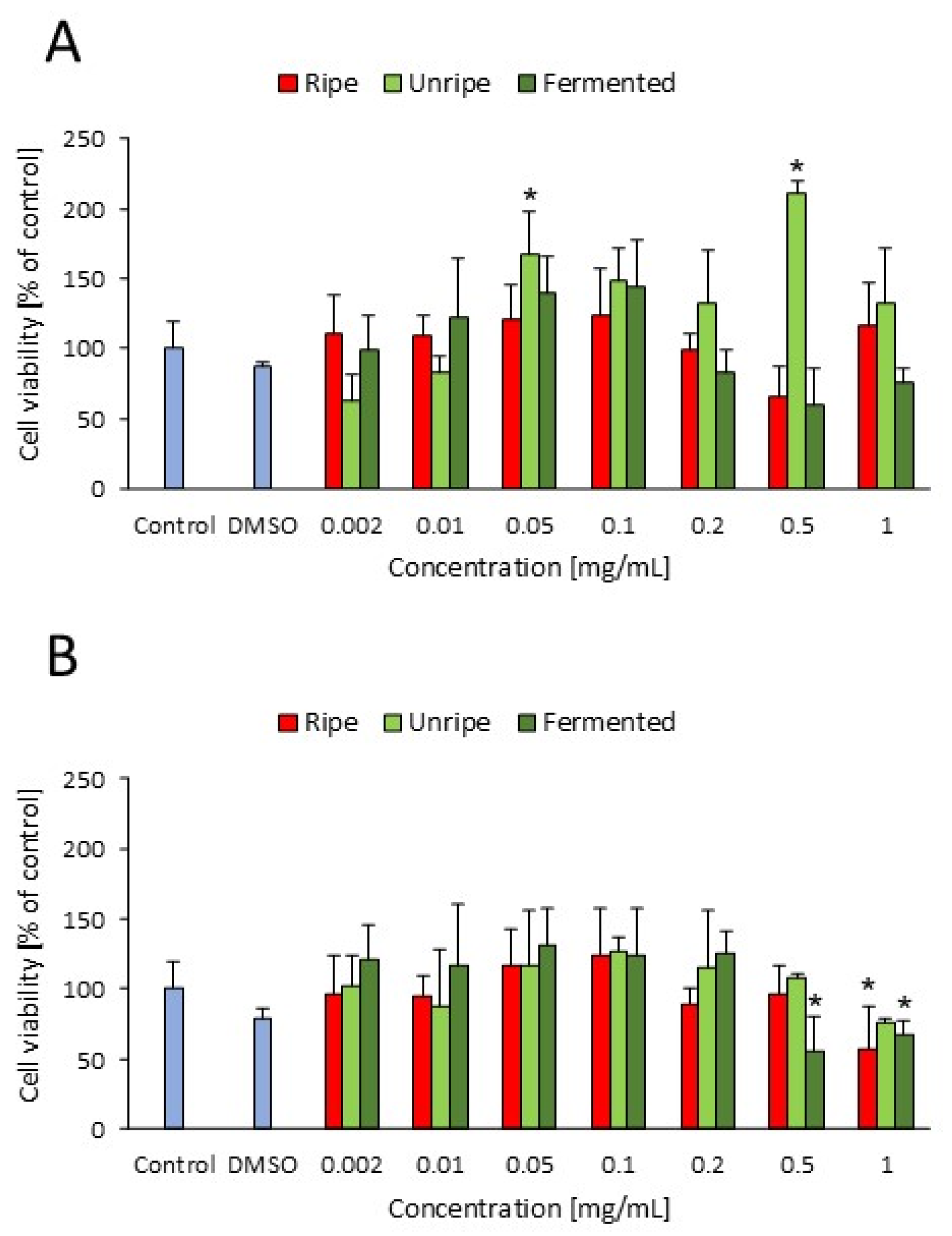

2.6. Effect of C. mas Extracts on Cellular Viability

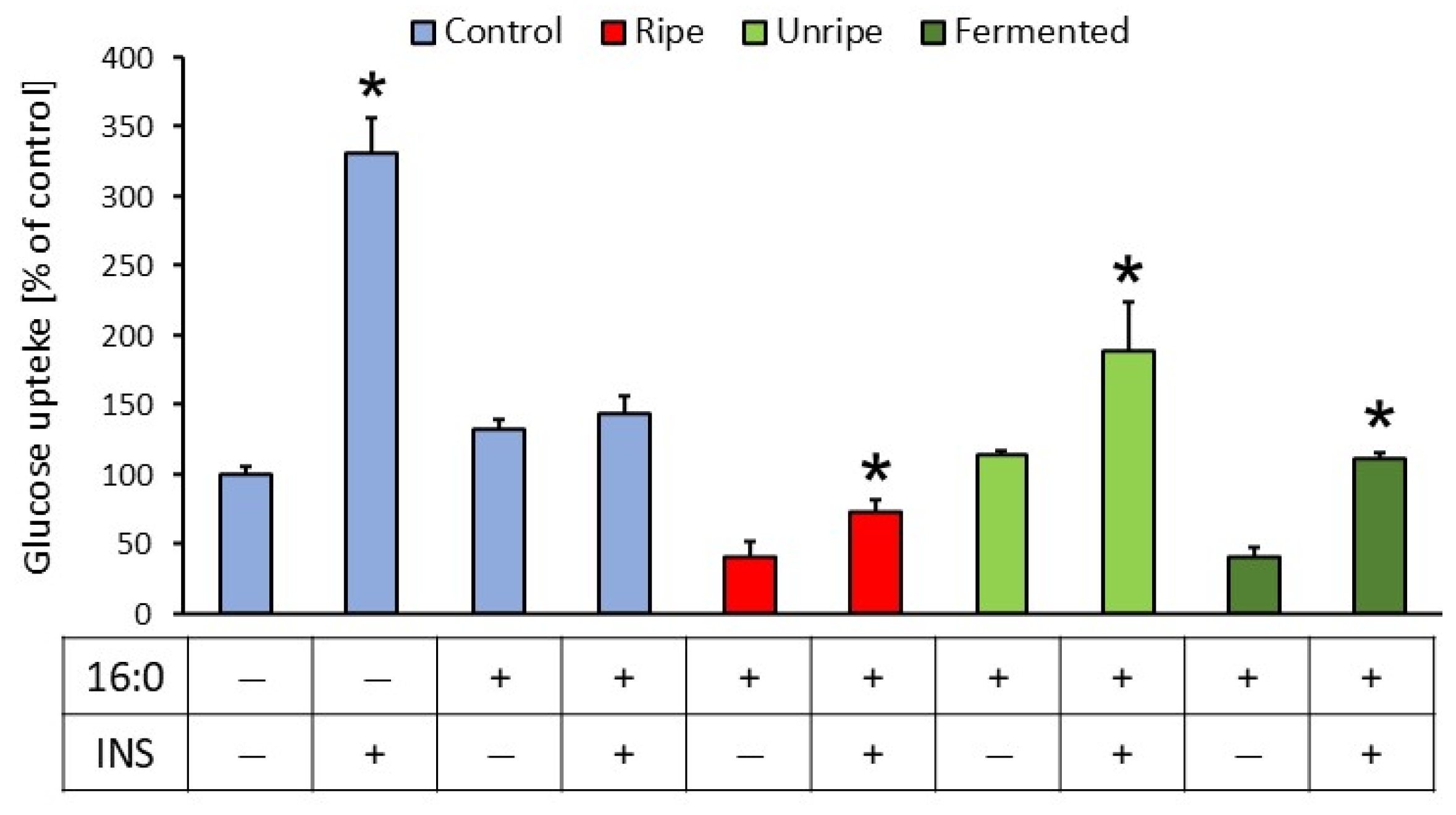

2.7. Effect of C. mas Extracts on Glucose Uptake and Expression of Insulin-Related Genes

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Reference Standards

3.2. Plant Material

3.3. Fermentation and Assessment of the Final Product

3.3.1. Bacterial DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification and High-Throughput Sequencing

3.3.2. Microbiological Analysis

3.3.3. Analysis of Microbial By-Products by HPLC-PDA and HPLC-RI

3.4. Fruit Extracts Preparation

3.5. Sample Preparation

3.6. Identification of Phenolic Compounds by UPLC-ESI-qTOF-MS/MS

3.7. Quantification of Phenolic Compounds by HPLC-PDA

3.8. Determination of Total Phenolic Content

3.9. Analysis of Antioxidant Capacity

3.10. α-Amylase Inhibition Assay

3.11. α-Glucosidase Inhibition Assay

3.12. Cell Culturing and Adipocyte Differentiation

3.13. Cell Viability

3.14. Insulin Resistance Induction and Glucose Uptake Test

3.15. RNA Isolation and Gene Expression

3.16. Statistical Analysis

3.17. Chemical Structures

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IR | Insulin resistance |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| TPC | Total phenolic content |

| LAB | Lactic acid bacteria |

| RF | Ripe fruit |

| UF | Unripe fruit |

| FF | Fermented fruit |

| SCOBY | Symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast |

| HHDP | Hexahydroxydiphenoyl |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| SAT | Subcutaneous adipose tissue |

| VAT | Visceral adipose tissue |

| ABTS | 2,2′-azinobis (3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| TPTZ | Potassium persulfate, 2,4,6-tri(2-pyridyl)-s-triazine |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| VRBD | Violet Red Bile Dextrose |

| TMC | Total mesophilic counts |

| PCA | Plate count agar |

| DRBC | Dichloran Rose Bengal Chloramphenicol |

| FRAP | Ferric-reducing antioxidant power |

References

- Lee, S.-H.; Park, S.-Y.; Choi, C.S. Insulin Resistance: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Strategies. Diabetes Metab. J. 2022, 46, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chi, X.; Wang, Y.; Setrerrahmane, S.; Xie, W.; Xu, H. Trends in Insulin Resistance: Insights into Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategy. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2022, 7, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; ISBN 978-2-930229-98-0. [Google Scholar]

- Papakonstantinou, E.; Oikonomou, C.; Nychas, G.; Dimitriadis, G.D. Effects of Diet, Lifestyle, Chrononutrition and Alternative Dietary Interventions on Postprandial Glycemia and Insulin Resistance. Nutrients 2022, 14, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahwan, M.; Alhumaydhi, F.; Ashraf, G.M.; Hasan, P.M.Z.; Shamsi, A. Role of Polyphenols in Combating Type 2 Diabetes and Insulin Resistance. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 206, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, S.; Li, K.; Liu, Z. Research on the Influences of Five Food-Borne Polyphenols on In Vitro Slow Starch Digestion and the Mechanism of Action. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 8617–8625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.-Y.; Zhao, D.-G.; Zhou, A.-Y.; Zhang, Y.; Du, Z.; Zhang, K. α-Glucosidase Inhibition and Antihyperglycemic Activity of Phenolics from the Flowers of Edgeworthia Gardneri. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 8162–8169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, S.; McClements, D.J.; Wan, Y.; Liu, C.; Fu, G. Antioxidant Activity and α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity of a Fermented Tannic Acid Product: Trigalloylglucose. LWT 2019, 112, 108249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, H.; Farzaei, M.H.; Khodarahmi, R. Polyphenols and Their Benefits: A Review. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 1700–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniewska-Krzeska, A.; Ivanišová, E.; Klymenko, S.; Bieniek, A.A.; Šramková, K.F.; Brindza, J. Nutrients Content and Composition in Different Morphological Parts of Cornelian Cherry (Cornus mas L.). Agrobiodivers. Improv. Nutr. Health Life Qual. 2022, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klymenko, S.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Sokół-Łętowska, A.; Piórecki, N.; Przybylska, D.; Grygorieva, O. Iridoids, Flavonoids, and Antioxidant Capacity of Cornus mas, C. officinalis, and C. mas × C. officinalis Fruits. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylska, D.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Sozański, T. A Review on Bioactive Iridoids in Edible Fruits—from Garden to Food and Pharmaceutical Products. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 6447–6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenuta, M.C.; Deguin, B.; Loizzo, M.R.; Cuyamendous, C.; Bonesi, M.; Sicari, V.; Trabalzini, L.; Mitaine-Offer, A.-C.; Xiao, J.; Tundis, R. An Overview of Traditional Uses, Phytochemical Compositions and Biological Activities of Edible Fruits of European and Asian Cornus Species. Foods 2022, 11, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.; Kim, Y.-J.; Shin, Y. Assessment of Physicochemical Quality, Antioxidant Content and Activity, and Inhibition of Cholinesterase between Unripe and Ripe Blueberry Fruit. Foods 2020, 9, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, L.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V.; Forney, C.F.; Eaton, L. Characterization of Changes in Polyphenols, Antioxidant Capacity and Physico-Chemical Parameters during Lowbush Blueberry Fruit Ripening. Antioxidants 2013, 2, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przybylska, D.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Piórecki, N.; Sozański, T. The Health-Promoting Quality Attributes, Polyphenols, Iridoids and Antioxidant Activity during the Development and Ripening of Cornelian Cherry (Cornus mas L.). Antioxidants 2024, 13, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fecka, I.; Nowicka, A.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Sokół-Łętowska, A. The Effect of Strawberry Ripeness on the Content of Polyphenols, Cinnamates, L-Ascorbic and Carboxylic Acids. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 95, 103669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobori, R.; Yakami, S.; Kawasaki, T.; Saito, A. Changes in the Polyphenol Content of Red Raspberry Fruits During Ripening. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska, A.Z. Characteristics of Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Cornelian Cherry Fruit Fermented in Brine. Zesz. Probl. Postęp. Nauk Rol. 2011, 566, 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, W.; Zhang, P.; Ying, D.; Adhikari, B.; Fang, Z. Fermentation Transforms the Phenolic Profiles and Bioactivities of Plant-Based Foods. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 49, 107763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małodobra-Mazur, M.; Cierzniak, A.; Ryba, M.; Sozański, T.; Piórecki, N.; Kucharska, A.Z. Cornus mas L. Increases Glucose Uptake and the Expression of PPARG in Insulin-Resistant Adipocytes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyżowska, A.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Nowak, A.; Sokół-Łętowska, A.; Motyl, I.; Piórecki, N. Suitability of the Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains as the Starter Cultures in Unripe Cornelian Cherry (Cornus mas L.) Fermentation. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 2936–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.-J.; Lim, J.-Y.; Kang, M.-J.; Choi, J.-Y.; Yang, J.-H.; Chung, Y.B.; Park, S.H.; Min, S.G.; Lee, M.-A. Changes in Bacterial Composition and Metabolite Profiles during Kimchi Fermentation with Different Garlic Varieties. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulido, R.P.; Omar, N.B.; Abriouel, H.; López, R.L.; Cañamero, M.M.; Gálvez, A. Microbiological Study of Lactic Acid Fermentation of Caper Berries by Molecular and Culture-Dependent Methods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 7872–7879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucharska, A.Z.; Szumny, A.; Sokół-Łętowska, A.; Piórecki, N.; Klymenko, S.V. Iridoids and Anthocyanins in Cornelian Cherry (Cornus mas L.) Cultivars. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2015, 40, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Sozański, T.; Lee, C.-G.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Przybylska, D.; Piórecki, N.; Jeong, S.-Y. A Comparison of the Antiosteoporotic Effects of Cornelian Cherry (Cornus mas L.) Extracts from Red and Yellow Fruits Containing Different Constituents of Polyphenols and Iridoids in Osteoblasts and Osteoclasts. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 4122253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylska, D.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Cybulska, I.; Sozański, T.; Piórecki, N.; Fecka, I. Cornus mas L. Stones: A Valuable By-Product as an Ellagitannin Source with High Antioxidant Potential. Molecules 2020, 25, 4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.-J.; Pi, W.-X.; Zhu, G.-F.; Wei, W.; Lu, T.-L.; Mao, C.-Q. Quality Evaluation of Raw and Processed Corni Fructus by UHPLC-QTOF-MS and HPLC Coupled with Color Determination. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2022, 218, 114842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokozawa, T.; Park, C.H.; Noh, J.S.; Tanaka, T.; Cho, E.J. Novel Action of 7-O-Galloyl-D-Sedoheptulose Isolated from Corni Fructus as a Hypertriglyceridaemic Agent. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2009, 61, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagórska-Dziok, M.; Ziemlewska, A.; Mokrzyńska, A.; Nizioł-Łukaszewska, Z.; Sowa, I.; Szczepanek, D.; Wójciak, M. Comparative Study of Cytotoxicity and Antioxidant, Anti-Aging and Antibacterial Properties of Unfermented and Fermented Extract of Cornus mas L. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; West, B.J.; Jensen, C.J. UPLC-TOF-MS Characterization and Identification of Bioactive Iridoids in Cornus mas Fruit. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2013, 2013, 710972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowska, A.M.; Camangi, F.; Braca, A. Quali-Quantitative Analysis of Flavonoids of Cornus mas L. (Cornaceae) Fruits. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 1257–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świerczewska, A.; Buchholz, T.; Melzig, M.F.; Czerwińska, M.E. In Vitro α-Amylase and Pancreatic Lipase Inhibitory Activity of Cornus mas L. and Cornus alba L. Fruit Extracts. J. Food Drug. Anal. 2019, 27, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzydzan, O.; Bila, I.Z.; Kucharska, A.; Brodyak, I.; Sybirna, N. Antidiabetic Effects of Extracts of Red and Yellow Fruits of Cornelian Cherries (Cornus mas L.) on Rats with Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes Mellitus. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 6459–6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.; Wang, K.-J.; Cheng, C.-S.; Yan, G.; Lu, W.-L.; Ge, J.-F.; Cheng, Y.-X.; Li, N. Bioactive Compounds from Cornus officinalis Fruits and Their Effects on Diabetic Nephropathy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 153, 840–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razgonova, M.; Zakharenko, A.; Pikula, K.; Manakov, Y.; Ercisli, S.; Derbush, I.; Kislin, E.; Seryodkin, I.; Sabitov, A.; Kalenik, T.; et al. LC-MS/MS Screening of Phenolic Compounds in Wild and Cultivated Grapes Vitis Amurensis Rupr. Molecules 2021, 26, 3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šuković, D.; Knežević, B.; Gašić, U.; Sredojević, M.; Ćirić, I.; Todić, S.; Mutić, J.; Tešić, Ž. Phenolic Profiles of Leaves, Grapes and Wine of Grapevine Variety Vranac (Vitis vinifera L.) from Montenegro. Foods 2020, 9, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendramin, V.; Viel, A.; Vincenzi, S. Caftaric Acid Isolation from Unripe Grape: A “Green” Alternative for Hydroxycinnamic Acids Recovery. Molecules 2021, 26, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatano, T.; Yasuhara, T.; Abe, R.; Okuda, T. A Galloylated Monoterpene Glucoside and a Dimeric Hydrolysable Tannin from Cornus officinalis. Phytochemistry 1990, 29, 2975–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatano, T.; Ogawa, N.; Kira, R.; Yasuhara, T.; Okuda, T. Tannins of Cornaceous Plants. I. Cornusiins A, B and C, Dimeric Monomeric and Trimeric Hydrolyzable Tannins from Cornus officinalis, and Orientation of Valoneoyl Group in Related Tannins. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1989, 37, 2083–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatano, T.; Yasuhara, T.; Okuda, T. Tannins of Cornaceous Plants. II.: Cornusiins D, E and F, New Dimeric and Trimeric Hydrolyzable Tannins from Cornus officinalis. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1989, 37, 2665–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska, A.Z.; Fecka, I. Identification of Iridoids in Edible Honeysuckle Berries (Lonicera caerulea L. Var. Kamtschatica Sevast.) by UPLC-ESI-qTOF-MS/MS. Molecules 2016, 21, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, H.; Rivas, B.d.l.; Gómez-Cordovés, C.; Muñoz, R. Degradation of Tannic Acid by Cell-Free Extracts of Lactobacillus Plantarum. Food Chem. 2008, 107, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zou, F.; Liu, W. Recent Advancement in Prevention against Hepatotoxicity, Molecular Mechanisms, and Bioavailability of Gallic Acid, a Natural Phenolic Compound: Challenges and Perspectives. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1549526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lidiková, J.; Čeryová, N.; Grygorieva, O.; Bobková, A.; Bobko, M.; Árvay, J.; Šnirc, M.; Brindza, J.; Ňorbová, M.; Harangozo, Ľ.; et al. Cornelian Cherry (Cornus mas L.) as a Promising Source of Antioxidant Phenolic Substances and Minerals. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 1745–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepaniak, O.; Cielecka-Piontek, J.; Kobus-Cisowska, J. Hypoglycaemic, Antioxidative and Phytochemical Evaluation of Cornus mas Varieties. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paun, G.; Neagu, E.; Albu, C.; Alecu, A.; Seciu-Grama, A.-M.; Radu, G.L. Antioxidant and Antidiabetic Activity of Cornus mas L. and Crataegus monogyna Fruit Extracts. Molecules 2024, 29, 3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, M.; Wojdyło, A. Inhibition of α-Amylase, α-Glucosidase, Pancreatic Lipase, 15-Lipooxygenase and Acetylcholinesterase Modulated by Polyphenolic Compounds, Organic Acids, and Carbohydrates of Prunus domestica Fruit. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Liu, D.; jin, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, J.; Li, H.; Li, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H. In Vitro and In Vivo Inhibitory Effect of Anthocyanin-Rich Bilberry Extract on α-Glucosidase and α-Amylase. LWT 2021, 145, 111484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Pereira, E.; Vinholes, J.R.; Camargo, T.M.; Nora, F.R.; Crizel, R.L.; Chaves, F.; Nora, L.; Vizzotto, M. Characterization of Araçá Fruits (Psidium cattleianum Sabine): Phenolic Composition, Antioxidant Activity and Inhibition of α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase. Food Biosci. 2020, 37, 100665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendine, M.; Marino, M.; Martini, D.; Riso, P.; Møller, P.; Del Bo’, C. Effect of (Poly)Phenols on Lipid and Glucose Metabolisms in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes: An Integrated Analysis of Mechanistic Approaches. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2025, 14, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska-Wasielica, J.; Olejnik, A.; Kowalska, K.; Olkowicz, M.; Dembczyński, R. Elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.) Fruit Extract Alleviates Oxidative Stress, Insulin Resistance, and Inflammation in Hypertrophied 3T3-L1 Adipocytes and Activated RAW 264.7 Macrophages. Foods 2019, 8, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Variya, B.C.; Bakrania, A.K.; Patel, S.S. Antidiabetic Potential of Gallic Acid from Emblica officinalis: Improved Glucose Transporters and Insulin Sensitivity through PPAR-γ and Akt Signaling. Phytomedicine 2020, 73, 152906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.H.; Yu, J.S.; Lee, H.S.; Choi, C.-I.; Kim, K.H. Antidiabetic Flavonoids from Fruits of Morus alba Promoting Insulin-Stimulated Glucose Uptake via Akt and AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Activation in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolmie, M.; Bester, M.J.; Serem, J.C.; Nell, M.; Apostolides, Z. The Potential Antidiabetic Properties of Green and Purple Tea [Camellia sinensis (L.) O Kuntze], Purple Tea Ellagitannins, and Urolithins. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 309, 116377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6887-1:2017; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Preparation of Test Samples, Initial Suspension and Decimal Dilutions for Microbiological Examination—Part 1: General Rules for the Preparation of the Initial Suspension and Decimal Dilutions. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Gao, X.; Ohlander, M.; Jeppsson, N.; Björk, L.; Trajkovski, V. Changes in Antioxidant Effects and Their Relationship to Phytonutrients in Fruits of Sea Buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) During Maturation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 1485–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, G.-C.; Chen, H.-Y. Antioxidant Activity of Various Tea Extracts in Relation to Their Antimutagenicity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1995, 43, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsędek, A.; Majewska, I.; Redzynia, M.; Sosnowska, D.; Koziołkiewicz, M. In Vitro Inhibitory Effect on Digestive Enzymes and Antioxidant Potential of Commonly Consumed Fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 4610–4617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małodobra-Mazur, M.; Cierzniak, A.; Pawełka, D.; Kaliszewski, K.; Rudnicki, J.; Dobosz, T. Metabolic Differences between Subcutaneous and Visceral Adipocytes Differentiated with an Excess of Saturated and Monounsaturated Fatty Acids. Genes 2020, 11, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Variant of Fermented Cornelian Cherry Fruits | Enterobacteriaceae | Yeasts | Molds | Lactic Acid Bacteria | Total Mesophilic Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cornelian cherry | 2.98 ± 0.06 | 5.49 ± 0.10 | <1 | <1 | 5.58 ± 0.42 |

| 2 | Cornelian cherry + L. brevis ZP HE1 | 2.00 ± 0.60 | 3.08 ± 0.36 | 1.48 ± 0.25 | 5.87 ± 0.61 | 5.90 ± 0.48 |

| 3 | Cornelian cherry + thyme | <1 | 5.58 ± 0.03 | <1 | <1 | 5.38 ± 0.62 |

| 4 | Cornelian cherry + thyme + inulin | <1 | 6.41 ± 0.74 | <1 | <1 | 6.43 ± 0.09 |

| 5 | Cornelian cherry + thyme + inulin + L. brevis ZP HE1 | <1 | 4.75 ± 0.34 | <1 | 6.99 ± 0.70 | 4.81 ± 0.56 |

| No. | Variant of Fermented Cornelian Cherry Fruits | Lactic Acid | Acetic Acid | Propionic Acid | Ethanol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [mg/100 mL] | [mg/100 mL] | [mg/100 mL] | [%] | ||

| 1 | Cornelian cherry | 132 ± 1.90 | 86.3 ± 0.50 | 295 ± 1.00 | 1.52 ± 0.20 |

| 2 | Cornelian cherry + L. brevis ZP HE1 | 458 ± 6.00 | 95.2 ± 7.05 | 121 ± 0.63 | 1.30 ± 0.09 |

| 3 | Cornelian cherry + thyme | 155 ± 2.11 | 43.9 ± 0.50 | 99.0 ± 5.00 | 0.34 ± 0.05 |

| 4 | Cornelian cherry + thyme + inulin | 78.5 ± 2.03 | 83.1 ± 0.48 | 105 ± 0.60 | 1.21 ± 0.02 |

| 5 | Cornelian cherry + thyme + inulin + L. brevis ZP HE1 | 519 ± 9.06 | 134 ± 2.00 | 84.4 ± 2.60 | 0.47 ± 0.10 |

| No. | tR (min) | MS1 (m/z) | MS2 Other Ions (m/z) | Assigned Identification | References | Fruit Extract |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive ion mode, ESI+ | ||||||

| 1 | 3.69 | 449 | 287 | Cyanidin 3-O-galactoside | [25,26] | RF |

| 2 | 3.93 | 595 | 287 | Cyanidin 3-O-robinobioside | [25,26] | RF |

| 3 | 4.19 | 433 | 271 | Pelargonidin 3-O-galactoside | [25,26] | RF |

| 4 | 4.43 | 579 | 271 | Pelargonidin 3-O-robinobioside | [25,26] | RF |

| Negative ion mode, ESI− | ||||||

| 5 | 1.47 | 331 | 169, 125 | Mono-O-galloyl-β-D-glucose | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 6 | 1.61 | 169 | 125 | Gallic acid | [28] | RF, UF, FF |

| 7 | 1.86 | 361 | 169, 125 | 7-O-galloyl-D-sedoheptulose | [28,29,30] | RF, UF, FF |

| 8 | 2.21 | 633 | 301, 275, 249, 169, 125 | Gemin D | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 9 | 2.66 | 783 | 481, 331, 301, 275, 169, 125 | Bis-HDDP-hexoside (1) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 10 | 2.98 | 1417 708 [M − 2H]−2 | 1245, 1115, 785, 765, 633, 613, 450, 301, 275, 168, 125 | Camptothin A (1) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 11 | 3.19 | 311 | 179, 149 | trans-Caftaric acid | [26,28] | RF, UF, FF |

| 12 | 3.40 | 1417 708 [M − 2H]−2 | 1247, 785, 765, 633, 613, 451, 301, 275, 169, 125 | Camptothin A (2) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 13 | 3.43 | 341 | 211, 195, 163 | p-Coumaric acid derivative | [26] | RF, UF, FF |

| 14 | 3.61 | 783 | 633, 481, 301, 275, 249 | Bis-HDDP-hexoside (2) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 15 | 3.78 | 375 751 [2M − H]− 1127 [3M − H]− | 213, 195, 169, 151, 125, 101 | Loganic acid | [26,28] | RF, UF, FF |

| 16 | 3.82 | 1100 [M − 2H]−2 | 1569, 1417, 1247, 785, 765, 633, 613, 483, 451, 313, 301, 275, 271, 249, 169, 125 | Cornusiin F (1) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 17 | 3.89 | 1417 708 [M − 2H]−2 | 1247, 935, 785, 765, 633, 613, 451, 301, 275, 249, 169, 125 | Campthothin A (3) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 18 | 4.06 | 2201 1100 [M − 2H]−2 | 1567, 1247, 785, 765, 633, 613, 483, 301, 169, 125 | Cornusiin F (2) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 19 | 4.10 | 785 | 765, 633, 483, 451, 313, 301, 275, 249, 169, 125 | Tellimagrandin I (1) | [27,28] | RF, UF, FF |

| 20 | 4.29 | 635 | 313, 169, 125 | Tri-O-galloyl-β-D-glucose | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 21 | 4.34 | 1569 784 [M − 2H]−2 | 1417, 1247, 935, 785, 765, 633, 451, 301, 275, 249, 169, 125 | Cornusiin A (1) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 22 | 4.40 | 1100 [M − 2H]−2 | 1569, 785, 765, 633, 613, 483, 451, 313, 301, 275, 271, 249, 169, 125 | Cornusiin F (3) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 23 | 4.87 | 1100 [M − 2H]−2 | 1569, 1247, 933, 785, 765, 633, 613, 483, 451, 313, 301, 275, 271, 249, 169, 125 | Cornusiin F (4) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 24 | 4.90 | 2353 1176 [M − 2H]−2 | 935, 785, 633, 451, 331, 301, 275, 249, 169, 125 | Cornusiin C (1) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 25 | 4.90 | 785 | 765, 633, 483, 450, 313, 301, 275, 249, 168, 125 | Tellimagrandin I (2) | [27,28] | RF, UF, FF |

| 26 | 4.97 | 784 [M − 2H]−2 | 935, 785, 765, 633, 465, 451, 301, 275, 249, 169, 125 | Cornusiin A (2) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 27 | 5.04 | 295 | 163, 149 | cis-Coutaric acid | [26] | RF, UF, FF |

| 28 | 5.22 | 1569 784 [M − 2H]−2 | 1249, 935, 785, 765, 633, 613, 483, 451, 331, 313, 301, 275, 249, 125 | Cornusiin A (3) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 29 | 5.39 | 1569 784 [M − 2H]−2 | 1249, 935, 785, 765, 633, 613, 483, 451, 331, 313, 275, 249, 169, 125 | Cornusiin A (4) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 30 | 5.46 | 2353 1176 [M − 2H]−2 | 1569, 1247, 933, 785, 765, 633, 451, 301, 275, 249, 169, 125 | Cornusiin C (2) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 31 | 5.60 | 2353 1176 [M − 2H]−2 | 1569, 1249, 935, 785, 765, 633, 301, 275, 249, 169, 125 | Cornusiin C (3) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 32 | 5.70 | 1176 [M − 2H]−2 | 1569, 785, 765, 633, 465, 451, 301, 275, 249, 169, 125 | Cornusiin C (4) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 33 | 5.74 | 357 403 [M − H + HCOO]− | 149, 195, 125, 101 | Sweroside | [28,31] | RF, UF, FF |

| 34 | 5.78 | 860 [M − 2H]−2 | 937, 935, 785, 633, 451, 301, 275, 249, 169, 125 | Camptothin B or Cornusiin D (1) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 35 | 5.81 | 784 [M − 2H]−2 | 935, 785, 768, 633, 483, 451, 425, 331, 301, 275, 249, 169, 125 | Cornusiin A (5) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 36 | 5.88 | 860 [M − 2H]−2 | 937, 785, 633, 451, 301, 275, 249, 169, 125 | Camptothin B or Cornusiin D (2) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 37 | 5.95 | 389 435 [M − H + HCOO]− | 227, 209, 197, 131, 101 | Loganin | [28,31] | RF, UF, FF |

| 38 | 6.12 | 1176 [M − 2H]−2 | 935, 785, 633, 451, 331, 301, 275, 249, 169, 125 | Cornusiin C (5) | [27] | UF |

| 39 | 6.16 | 1569 784 [M − 2H]−2 | 1417, 935, 785, 765, 633, 483, 451, 425, 331, 301, 275, 249, 169, 125 | Cornusiin A (6) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 40 | 6.26 | 937 | 785, 465, 447, 313, 301, 275, 249, 169, 125 | Tellimagrandin II | [27] | UF, FF |

| 41 | 6.27 | 2353 1176 [M − 2H]−2 | 1569, 1417, 937, 785, 633, 613, 451, 301, 275, 249, 169, 125 | Cornusiin C (6) | [27] | RF, UF |

| 42 | 6.51 | 787 | 617, 465, 313, 169, 125 | Tetra-O-galloyl-β-D-glucose (1) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 43 | 6.53 | 609 | 301 | Quercetin 3-O-rutinoside | [32] | RF, UF |

| 44 | 6.62 | 463 | 301 | Quercetin 3-O-galactoside or glucoside | [32,33] | RF, UF |

| 45 | 6.62 | 787 | 617, 313, 169, 125 | Tetra-O-galloyl-β-D-glucose (2) | [27] | UF |

| 46 | 6.76 | 301 | 275, 249 | Ellagic acid | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 47 | 6.76 | 477 | 301 | Quercetin 3-O-glucuronide | [33,34] | RF, UF, FF |

| 48 | 6.90 | 1176 [M − 2H]−2 | 1569, 935, 785, 633, 451, 301, 275, 249, 169, 125 | Cornusiin C (7) | [27] | RF, UF, FF |

| 49 | 7.14 | 1569 784 [M − 2H]−2 | 1417, 935, 785, 765, 633, 451, 425, 331, 301, 275, 249, 169, 125 | Cornusiin A (7) | [27] | RF, UF |

| 50 | 7.25 | 447 | 285 | Kaempferol 3-O-glucoside | [28,32,33] | RF, UF |

| 51 | 7.31 | 593 | 285 | Kaempferol 3-O-rutinoside | [35] | RF |

| 52 | 7.46 | 447 | 285 | Kaempferol 3-O-galactoside | [32,35] | RF, UF |

| 53 | 7.95 | 541 | 169 | Cornuside | [25,31] | RF, UF, FF |

| No. | Compound | Ripe Fruit Extract | Unripe Fruit Extract | Fermented Fruit Extract |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthocyanins | ||||

| 1 | Cyanidin 3-O-galactoside | 2.71 ± 0.02 | n.a. | n.a. |

| 2 | Cyanidin 3-O-robinobioside | 0.75 ± 0.01 | n.a. | n.a. |

| 3 | Pelargonidin 3-O-galactoside | 1.30 ± 0.01 | n.a. | n.a. |

| 4 | Pelargonidin 3-O-robinobioside | 0.09 ± 0.00 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Phenolic acids | ||||

| 6 | Gallic acid | 2.26 ± 0.05 b | 3.51 ± 0.14 b | 18.6 ± 0.82 a |

| 11 | trans-Caftaric acid | 1.07 ± 0.03 a | 0.73 ± 0.03 b | 0.37 ± 0.01 c |

| 13 | p-Coumaric acid derivative | 0.65 ± 0.01 c | 0.89 ± 0.03 b | 0.98 ± 0.03 a |

| 27 | cis-Coutaric acid | 1.30 ± 0.01 b | 1.22 ± 0.07 b | 1.50 ± 0.06 a |

| 46 | Ellagic acid | 0.22 ± 0.06 c | 0.98 ± 0.04 a | 0.85 ± 0.03 b |

| Flavonols | ||||

| 43 | Quercetin 3-O-rutinoside | 0.95 ± 0.02 | t.a. | n.a. |

| 44 | Quercetin 3-O galactoside or glucoside | 3.04 ± 0.01 | t.a. | n.a. |

| 47 | Quercetin 3-O-glucuronide | 1.10 ± 0.02 b | 2.37 ± 0.10 a | 1.11 ± 0.01 b |

| 50 | Kaempferol 3-O-glucoside | 0.10 ± 0.00 | t.a. | n.a. |

| 52 | Kaempferol 3-O-galactoside | 1.29 ± 0.00 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Iridoids | ||||

| 15 | Loganic acid | 313 ± 8.11 a | 190 ± 8.41 b | 211 ± 9.48 b |

| 33 | Sweroside | 15.7 ± 0.10 a | 12.1 ± 1.75 b | 12.6 ± 0.45 ab |

| 53 | Cornuside | 16.5 ± 0.27 a | 12.2 ± 0.55 b | 12.1 ± 0.49 b |

| Hydrolyzable tannins | ||||

| 5 | Mono-O-galloyl-β-D-glucose | 11.6 ± 0.25 b | 15.8 ± 0.74 a | 13.2 ± 0.68 b |

| 7 | 7-O-galloyl-D-sedoheptulose | 8.79 ± 0.23 b | 12.4 ± 0.58 a | 9.76 ± 0.41 b |

| 10 | Camptothin A (1) | 2.46 ± 0.62 c | 8.26 ± 0.64 a | 4.35 ± 0.40 b |

| 12 | Camptothin A (2) | 2.04 ± 0.09 b | 6.55 ± 1.37 a | 3.53 ± 0.38 b |

| 21 | Cornusiin A (1) | 4.10 ± 0.40 b | 14.1 ± 1.69 a | 6.71 ± 0.39 b |

| 28 | Cornusiin A (3) | 5.83 ± 0.09 b | 18.2 ± 2.29 a | 10.0 ± 0.25 b |

| Extract | TPC (g GAE/100 g Extract) | ABTS | DPPH | FRAP | α-Amylase | α-Glucosidase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition | ||||||

| (mmol Tx/100 g Extract) | (IC50 [mg/mL]) | |||||

| Ripe fruit | 25.9 ± 0.61 c | 222 ± 2.45 c | 191 ± 1.71 c | 163± 6.34 c | 1.95 ± 0.14 | 1.83 ± 0.12 |

| Unripe fruit | 51.4 ± 0.19 a | 351 ± 2.67 a | 291 ± 1.39 a | 251 ± 2.03 a | 1.71 ± 0.59 | 1.78 ± 0.02 |

| Fermented fruit | 37.8 ± 0.89 b | 333 ± 0.53 b | 261 ± 1.26 b | 225 ± 2.46 b | 1.88 ± 0.01 | 1.97 ± 0.08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bernacka, K.; Czyżowska, A.; Małodobra-Mazur, M.; Ołdakowska, M.; Otlewska, A.; Sozański, T.; Kucharska, A.Z. Chemical Composition and In Vitro Antidiabetic Effect of Extracts from Ripe, Unripe, and Fermented Unripe Cornus mas L. Fruits. Molecules 2025, 30, 4625. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234625

Bernacka K, Czyżowska A, Małodobra-Mazur M, Ołdakowska M, Otlewska A, Sozański T, Kucharska AZ. Chemical Composition and In Vitro Antidiabetic Effect of Extracts from Ripe, Unripe, and Fermented Unripe Cornus mas L. Fruits. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4625. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234625

Chicago/Turabian StyleBernacka, Karolina, Agata Czyżowska, Małgorzata Małodobra-Mazur, Monika Ołdakowska, Anna Otlewska, Tomasz Sozański, and Alicja Z. Kucharska. 2025. "Chemical Composition and In Vitro Antidiabetic Effect of Extracts from Ripe, Unripe, and Fermented Unripe Cornus mas L. Fruits" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4625. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234625

APA StyleBernacka, K., Czyżowska, A., Małodobra-Mazur, M., Ołdakowska, M., Otlewska, A., Sozański, T., & Kucharska, A. Z. (2025). Chemical Composition and In Vitro Antidiabetic Effect of Extracts from Ripe, Unripe, and Fermented Unripe Cornus mas L. Fruits. Molecules, 30(23), 4625. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234625