Functional and Mechanistic Insights of 3-Hydroxybutyrate (3-OBA) in Bladder Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

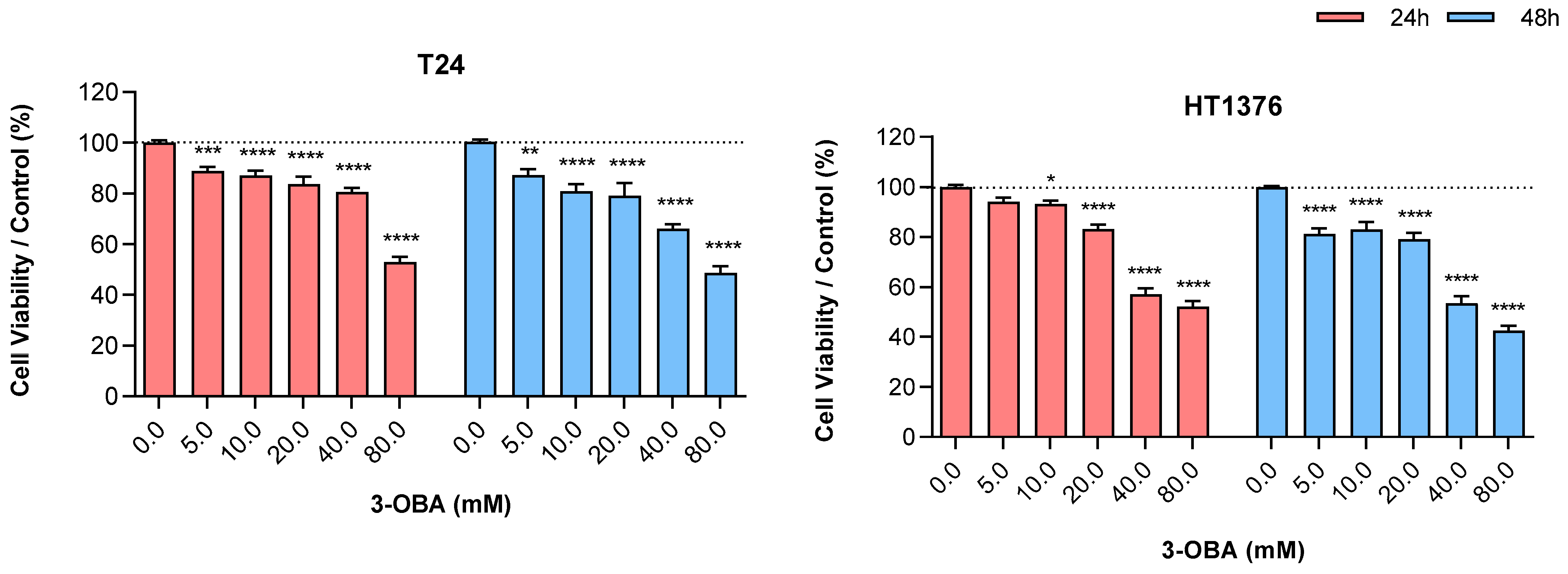

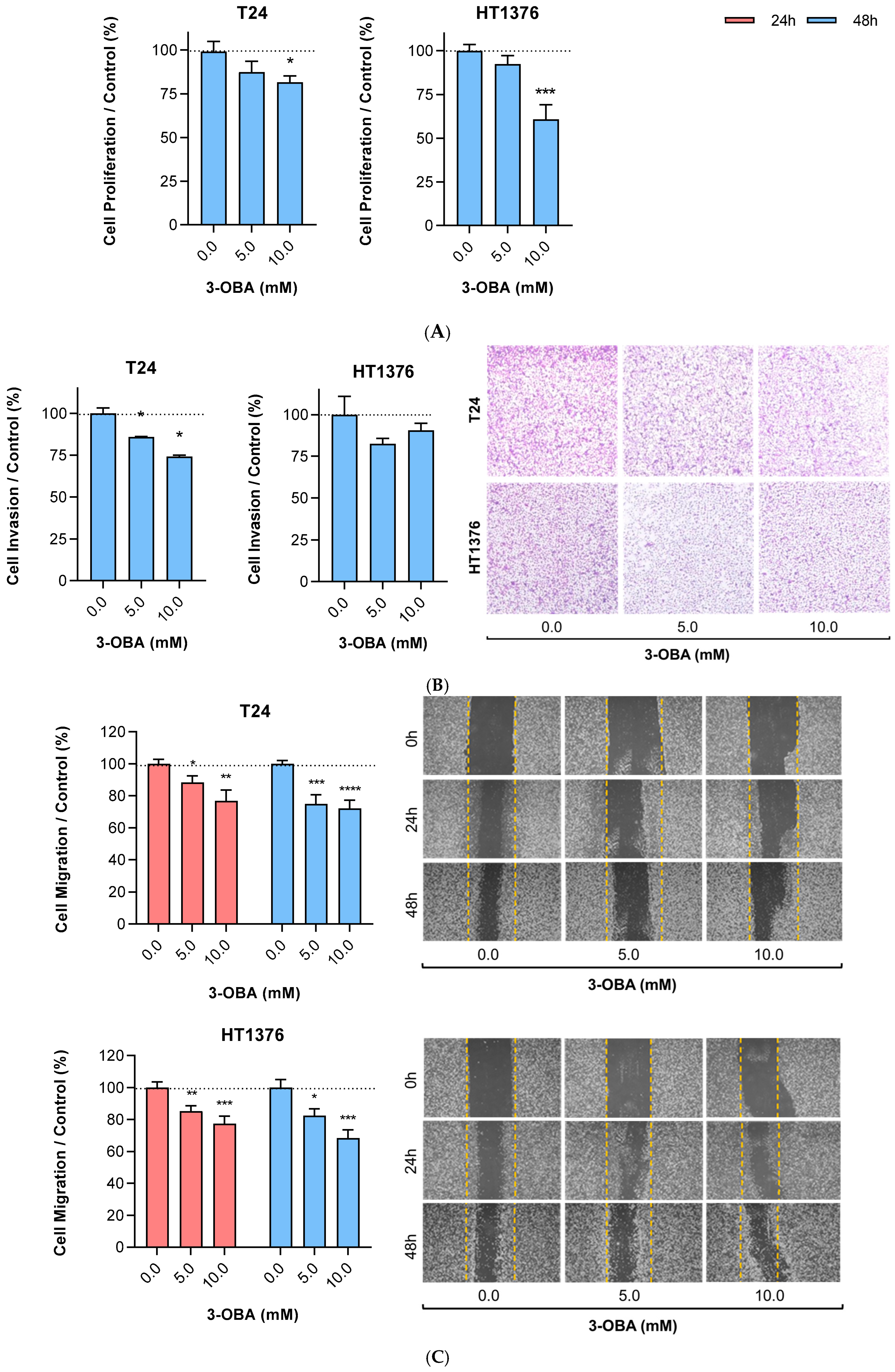

2.1. Effects of 3-OBA Treatment in Muscle-Invasive UBC Cell Lines

2.2. Effects of 3-OBA Treatment in Muscle-Invasive UBC Cell Lines-Derived Tumors

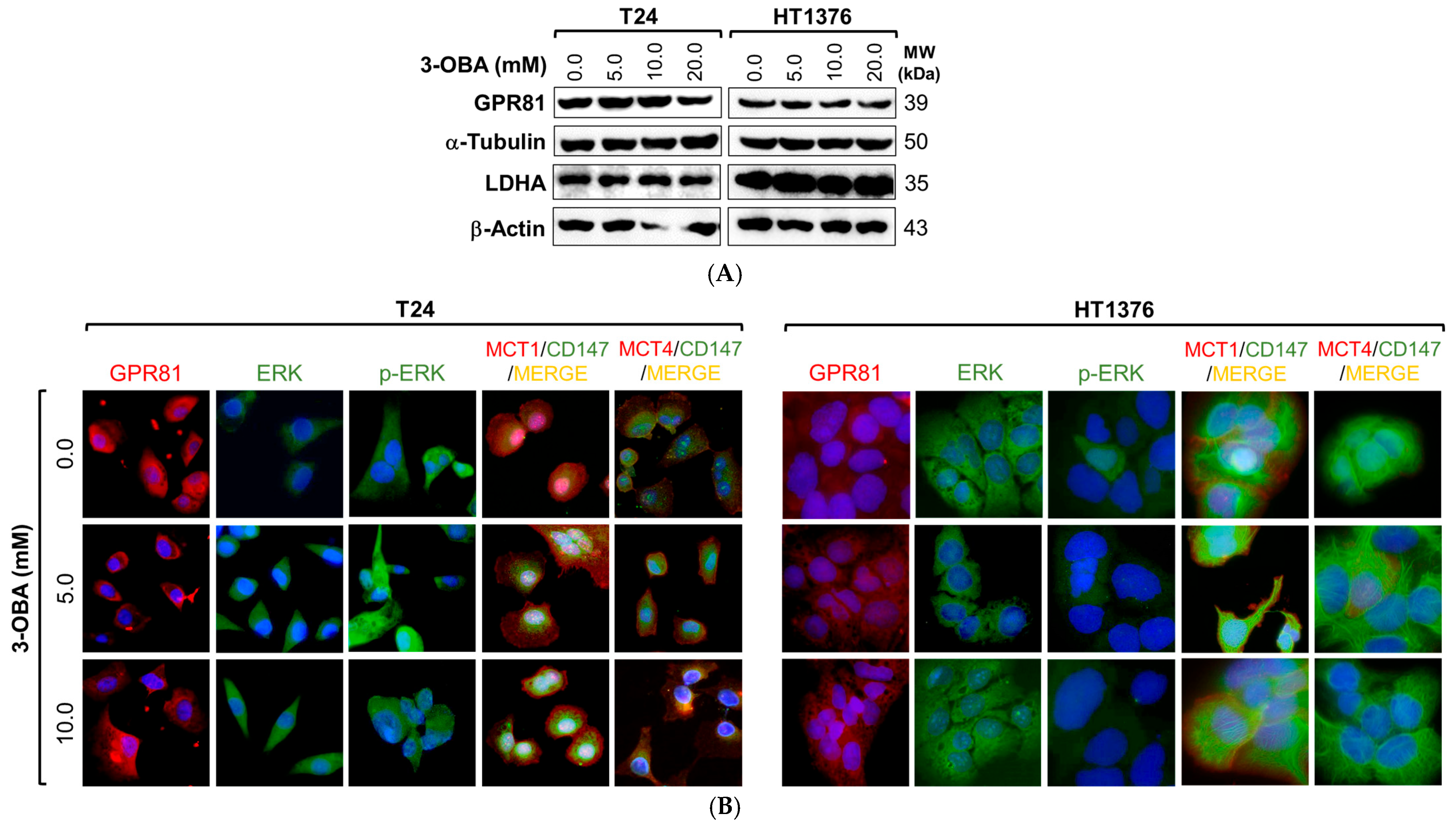

2.3. Mechanistic Insights of 3-OBA Treatment in Muscle-Invasive UBC Cell Lines

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Lines and Cell Culture Conditions

4.2. Cell Viability Assay

4.3. Cell Proliferation Assay

4.4. Cell Migration Assay

4.5. Cell Invasion Assay

4.6. Cell Cycle and Cell Death Analysis

4.7. Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane (CAM) Assay

4.8. Cell Lysis, Protein Extraction and Western Blotting

4.9. Immunofluorescence

4.10. Colorimetric Analysis of Extracellular Lactate

4.11. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanli, O.; Dobruch, J.; Knowles, M.A.; Burger, M.; Alemozaffar, M.; Nielsen, M.E.; Lotan, Y. Bladder cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaeli, J.C.; Boch, T.; Albers, S.; Michaeli, T.; Michaeli, D.T. Socio-economic burden of disease: Survivorship costs for bladder cancer. J. Cancer Policy 2022, 32, 100326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward Grados, D.F.; Ahmadi, H.; Griffith, T.S.; Warlick, C.A. Immunotherapy for Bladder Cancer: Latest Advances and Ongoing Clinical Trials. Immunol. Investig. 2022, 51, 2226–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franza, A.; Pirovano, M.; Giannatempo, P.; Cosmai, L. Erdafitinib in locally advanced/metastatic urothelial carcinoma with certain FGFR genetic alterations. Future Oncol. 2022, 18, 2455–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispen, P.L.; Kusmartsev, S. Mechanisms of immune evasion in bladder cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2020, 69, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Chen, Y.; Wu, D. FGFR-TKI resistance in cancer: Current status and perspectives. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, C.; Rosenberg, J.; Knowles, M. SnapShot: Bladder Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 350–350.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierziak, J.; Burgberger, M.; Wojtasik, W. 3-Hydroxybutyrate as a Metabolite and a Signal Molecule Regulating Processes of Living Organisms. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, G.F., Jr. Fuel metabolism in starvation. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2006, 26, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedkova, E.N.; Blatter, L.A. Role of beta-hydroxybutyrate, its polymer poly-beta-hydroxybutyrate and inorganic polyphosphate in mammalian health and disease. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J.C.; Verdin, E. Ketone bodies as signaling metabolites. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 25, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, C.S.; Ghai, R.; Rashmi; Kalia, V.C. Polyhydroxyalkanoates: An overview. Bioresour. Technol. 2003, 87, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, Y.; Gao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Yu, M.; Zhao, L.; Duan, Y.; Liu, Y. Breath ketone testing: A new biomarker for diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring of diabetic ketosis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 869186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosinski, C.; Jornayvaz, F.R. Effects of Ketogenic Diets on Cardiovascular Risk Factors: Evidence from Animal and Human Studies. Nutrients 2017, 9, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.N.; Li, L.; Hu, S.H.; Yang, Y.X.; Ma, Z.Z.; Huang, L.; An, Y.P.; Yuan, Y.Y.; Lin, Y.; Xu, W.; et al. Ketogenic diet-produced beta-hydroxybutyric acid accumulates brain GABA and increases GABA/glutamate ratio to inhibit epilepsy. Cell Discov. 2024, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, M.; Fernando, M.; Eslick, S.; Asih, P.R.; Shadfar, S.; Bandara, E.M.S.; Hillebrandt, H.; Meghwar, S.; Shahriari, M.; Chatterjee, P.; et al. Ketone bodies mediate alterations in brain energy metabolism and biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1297984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Cheng, X.; Zhou, T.; Li, D.; Peng, J.; Xu, Y.; Huang, W. beta-Hydroxybutyrate as an epigenetic modifier: Underlying mechanisms and implications. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Wei, F.; Su, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Fang, Y.; Ding, J.; Chen, Y. Histone deacetylase inhibitors promote breast cancer metastasis by elevating NEDD9 expression. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2023, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartmann, C.; Janaki Raman, S.R.; Floter, J.; Schulze, A.; Bahlke, K.; Willingstorfer, J.; Strunz, M.; Wockel, A.; Klement, R.J.; Kapp, M.; et al. Beta-hydroxybutyrate (3-OHB) can influence the energetic phenotype of breast cancer cells, but does not impact their proliferation and the response to chemotherapy or radiation. Cancer Metab. 2018, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirian, F.I.; Karimi, M.; Alipour, M.; Salami, S.; Nourbakhsh, M.; Nekufar, S.; Safari-Alighiarloo, N.; Tavakoli-Yaraki, M. Beta hydroxybutyrate induces lung cancer cell death, mitochondrial impairment and oxidative stress in a long term glucose-restricted condition. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, X.; Yang, X.; Li, W.; Li, S.; Hu, Z.; Ling, C.; Shi, R.; Liu, J.; Chen, G.; et al. Dual Blockade of Lactate/GPR81 and PD-1/PD-L1 Pathways Enhances the Anti-Tumor Effects of Metformin. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib-Massalha, E.; Bhattacharya, S.; Massalha, H.; Biram, A.; Golan, K.; Kollet, O.; Kumari, A.; Avemaria, F.; Petrovich-Kopitman, E.; Gur-Cohen, S.; et al. Lactate released by inflammatory bone marrow neutrophils induces their mobilization via endothelial GPR81 signaling. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Xu, J.; Fan, M.; Tu, F.; Wang, X.; Ha, T.; Williams, D.L.; Li, C. Lactate Suppresses Macrophage Pro-Inflammatory Response to LPS Stimulation by Inhibition of YAP and NF-kappaB Activation via GPR81-Mediated Signaling. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 587913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Cai, M.; Liu, Y.; Liu, B.; Xue, X.; Ji, R.; Bian, X.; Lou, S. The roles of GRP81 as a metabolic sensor and inflammatory mediator. J. Cell Physiol. 2020, 235, 8938–8950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltazar, F.; Afonso, J.; Costa, M.; Granja, S. Lactate Beyond a Waste Metabolite: Metabolic Affairs and Signaling in Malignancy. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.P.; Ganapathy, V. Lactate/GPR81 signaling and proton motive force in cancer: Role in angiogenesis, immune escape, nutrition, and Warburg phenomenon. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 206, 107451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, S.; Hata, K.; Hirose, K.; Okui, T.; Toyosawa, S.; Uzawa, N.; Nishimura, R.; Yoneda, T. The lactate sensor GPR81 regulates glycolysis and tumor growth of breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundo, K.; Dmytriyeva, O.; Spohr, L.; Goncalves-Alves, E.; Yao, J.; Blasco, L.P.; Trauelsen, M.; Ponniah, M.; Severin, M.; Sandelin, A.; et al. Lactate receptor GPR81 drives breast cancer growth and invasiveness through regulation of ECM properties and Notch ligand DLL4. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad Nezhady, M.A.; Chemtob, S. 3-OBA Is Not an Antagonist of GPR81. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 803907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehtiati, S.; Hatami, B.; Khatami, S.H.; Tajernarenj, K.; Abdi, S.; Sirati-Sabet, M.; Ghazizadeh Hashemi, S.A.H.; Ahmadzade, R.; Hamed, N.; Goudarzi, M.; et al. The Multifaceted Influence of Beta-Hydroxybutyrate on Autophagy, Mitochondrial Metabolism, and Epigenetic Regulation. J. Cell Biochem. 2025, 126, e70050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohena-Rivera, K.; You, S.; Kim, M.; Billet, S.; Ten Hoeve, J.; Gonzales, G.; Huang, C.; Heard, A.; Chan, K.S.; Bhowmick, N.A. Targeting ketone body metabolism in mitigating gemcitabine resistance. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e177840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Xie, Y.; Yu, J.; Sun, H.; Xiao, D.; Zhou, Y.; Bao, L.; Wang, H.; et al. OXCT1 Enhances Gemcitabine Resistance Through NF-kappaB Pathway in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 698302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Han, T.; Wang, T.; Gan, M.; Xie, C.; Yu, B.; Wang, J.B. OXCT1 regulates NF-kappaB signaling pathway through beta-hydroxybutyrate-mediated ketone body homeostasis in lung cancer. Genes Dis. 2023, 10, 352–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badameh, P.; Akhlaghi Tabar, F.; Mohammadipoor, N.; Rezaei, R.; Ranjkesh, R.; Maleki, M.H.; Vakili, O.; Shafiee, S.M. Differential effects of beta-hydroxybutyrate and alpha-ketoglutarate on HCT-116 colorectal cancer cell viability under normoxic and hypoxic low-glucose conditions: Exploring the role of SRC, HIF1alpha, ACAT1, and SIRT2 genes. Mol. Genet. Genom. MGG 2025, 300, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ding, J.; Zhu, Y.; Shi, J.; Liu, R.; Wu, C.; Han, L.; Zhang, M. beta-hydroxybutyrate, a ketone body, suppresses tumor growth, stemness, and invasive phenotypes in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2025, 26, 2516825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. beta-hydroxybutyrate inhibits malignant phenotypes of prostate cancer cells through beta-hydroxybutyrylation of indoleacetamide-N-methyltransferase. Cancer Cell. Int. 2024, 24, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, H.; Lu, X. The Beta-Hydroxybutyrate Suppresses the Migration of Glioma Cells by Inhibition of NLRP3 Inflammasome. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 38, 1479–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dmitrieva-Posocco, O.; Wong, A.C.; Lundgren, P.; Golos, A.M.; Descamps, H.C.; Dohnalova, L.; Cramer, Z.; Tian, Y.; Yueh, B.; Eskiocak, O.; et al. beta-Hydroxybutyrate suppresses colorectal cancer. Nature 2022, 605, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Wu, F.; Liu, G.; Chen, G.Q. Applications and Mechanism of 3-Hydroxybutyrate (3HB) for Prevention of Colonic Inflammation and Carcinogenesis as a Food Supplement. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2021, 65, e2100533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikami, D.; Kobayashi, M.; Uwada, J.; Yazawa, T.; Kamiyama, K.; Nishimori, K.; Nishikawa, Y.; Nishikawa, S.; Yokoi, S.; Taniguchi, T.; et al. beta-Hydroxybutyrate enhances the cytotoxic effect of cisplatin via the inhibition of HDAC/survivin axis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 142, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Yan, P.; Gong, H.; Li, G.; Wang, J. beta-hydroxybutyrate resensitizes colorectal cancer cells to oxaliplatin by suppressing H3K79 methylation in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, A.I.; Diaz, D.; Lin, B.; Krzesaj, P.K.; Ustoyev, S.; Shim, A.; Fine, E.J.; Sarafraz-Yazdi, E.; Pincus, M.R.; Feinman, R.D. Ketone Bodies Induce Unique Inhibition of Tumor Cell Proliferation and Enhance the Efficacy of Anti-Cancer Agents. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stransky, N.; Huber, S.M. Comment on Chen et al. Dual Blockade of Lactate/GPR81 and PD-1/PD-L1 Pathways Enhances the Anti-Tumor Effects of Metformin. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udumula, M.P.; Singh, H.; Faraz, R.; Poisson, L.; Tiwari, N.; Dimitrova, I.; Hijaz, M.; Gogoi, R.; Swenor, M.; Munkarah, A.; et al. Intermittent Fasting induced ketogenesis inhibits mouse epithelial ovarian tumors by promoting anti-tumor T cell response. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Outschoorn, U.E.; Lin, Z.; Whitaker-Menezes, D.; Howell, A.; Sotgia, F.; Lisanti, M.P. Ketone body utilization drives tumor growth and metastasis. Cell Cycle 2012, 11, 3964–3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sever, T.; Ellidokuz, E.B.; Basbinar, Y.; Ellidokuz, H.; Yilmaz, O.H.; Calibasi-Kocal, G. Beta-Hydroxybutyrate Augments Oxaliplatin-Induced Cytotoxicity by Altering Energy Metabolism in Colorectal Cancer Organoids. Cancers 2023, 15, 5724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Lv, J.; Li, T. Promoting the Anti-Tumor Activity of Radiotherapy on Lung Cancer through a Modified Ketogenic Diet and the AMPK Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2023, 117 (Suppl. S2), e268–e269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirobata, T.; Inaba, H.; Kaido, Y.; Kosugi, D.; Itoh, S.; Matsuoka, T.; Inoue, G. Serum ketone body measurement in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetol. Int. 2022, 13, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Park, I.B.; Yu, S.H.; Kim, S.K.; Kim, S.H.; Seo, D.H.; Hong, S.; Jeon, J.Y.; Kim, D.J.; Kim, S.W.; et al. Characterization of variable presentations of diabetic ketoacidosis based on blood ketone levels and major society diagnostic criteria: A new view point on the assessment of diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2019, 12, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Leite, R.; Carreira, I.; Melo, J.; Ferreira, S.I.; Ribeiro, I.; Ferreira, J.; Filipe, M.; Bernardo, C.; Arantes-Rodrigues, R.; Oliveira, P.; et al. Genomic characterization of three urinary bladder cancer cell lines: Understanding genomic types of urinary bladder cancer. Tumour Biol. 2014, 35, 4599–4617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonso, J.; Goncalves, C.; Costa, M.; Ferreira, D.; Santos, L.; Longatto-Filho, A.; Baltazar, F. Glucose Metabolism Reprogramming in Bladder Cancer: Hexokinase 2 (HK2) as Prognostic Biomarker and Target for Bladder Cancer Therapy. Cancers 2023, 15, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, J.; Barbosa-Matos, C.; Silvestre, R.; Pereira-Vieira, J.; Goncalves, S.M.; Mendes-Alves, C.; Parpot, P.; Pinto, J.; Carapito, A.; Guedes de Pinho, P.; et al. Cisplatin-Resistant Urothelial Bladder Cancer Cells Undergo Metabolic Reprogramming beyond the Warburg Effect. Cancers 2024, 16, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.; Jiang, L.; Yuan, Y.; Deng, T.; Zheng, Y.R.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Li, W.L.; Wu, J.Y.; Gao, J.Q.; Hu, W.W.; et al. Inhibition of G protein-coupled receptor 81 (GPR81) protects against ischemic brain injury. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2015, 21, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denisse, T.; Patrick, S.; Bruce, W. Differential expression and function of the endogenous lactate receptor, GPR81, in ERα-positive/HER2-positive epithelial vs. post-EMT triple-negative mesenchymal breast cancer cells. J. Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2019, 5, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Li, S.; Cui, Q.; Guo, B.; Ding, W.; Liu, J.; Quan, L.; Li, X.; Xie, P.; Jin, L.; et al. Activation of GPR81 by lactate drives tumour-induced cachexia. Nat. Metab. 2024, 6, 708–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Mao, X.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhao, C.; Li, G.; Guo, W.; Hu, Y. Lactate/GPR81 recruits regulatory T cells by modulating CX3CL1 to promote immune resistance in a highly glycolytic gastric cancer. Oncoimmunology 2024, 13, 2320951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, D.; Basaraba, R.J. Lactate Metabolism and Signaling in Tuberculosis and Cancer: A Comparative Review. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 624607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Ye, X.; Xie, M.; Ye, J. Induction of triglyceride accumulation and mitochondrial maintenance in muscle cells by lactate. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Fan, M.; Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Gill, P.S.; Ha, T.; Liu, L.; Hall, J.V.; Williams, D.L.; et al. Lactate induces vascular permeability via disruption of VE-cadherin in endothelial cells during sepsis. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm8965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohno, Y.; Oyama, A.; Kaneko, H.; Egawa, T.; Yokoyama, S.; Sugiura, T.; Ohira, Y.; Yoshioka, T.; Goto, K. Lactate increases myotube diameter via activation of MEK/ERK pathway in C2C12 cells. Acta Physiol. 2018, 223, e13042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roland, C.L.; Arumugam, T.; Deng, D.; Liu, S.H.; Philip, B.; Gomez, S.; Burns, W.R.; Ramachandran, V.; Wang, H.; Cruz-Monserrate, Z.; et al. Cell surface lactate receptor GPR81 is crucial for cancer cell survival. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 5301–5310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, M.B.; Srigley, J.R.; Grignon, D.J.; Reuter, V.E.; Humphrey, P.A.; Cohen, M.B.; Hammond, M.E.H. Urinary Bladder Cancer Protocols and Checklists; College of American Pathologists: Northfield, MN, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Edge, S.B.; Byrd, D.R.; Compton, C.C.; Fritz, A.G.; Greene, F.L.; Trotti, A. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual; Springer Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eble, J.N.; Sauter, G.; Epstein, J.I.; Sesterhenn, I.A. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs; IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva, A.; Félix, A.M.; Gonçalves, C.S.; Longatto-Filho, A.; Baltazar, F.; Afonso, J. Functional and Mechanistic Insights of 3-Hydroxybutyrate (3-OBA) in Bladder Cancer. Molecules 2025, 30, 4624. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234624

Silva A, Félix AM, Gonçalves CS, Longatto-Filho A, Baltazar F, Afonso J. Functional and Mechanistic Insights of 3-Hydroxybutyrate (3-OBA) in Bladder Cancer. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4624. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234624

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Ana, Ana Mafalda Félix, Céline S. Gonçalves, Adhemar Longatto-Filho, Fátima Baltazar, and Julieta Afonso. 2025. "Functional and Mechanistic Insights of 3-Hydroxybutyrate (3-OBA) in Bladder Cancer" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4624. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234624

APA StyleSilva, A., Félix, A. M., Gonçalves, C. S., Longatto-Filho, A., Baltazar, F., & Afonso, J. (2025). Functional and Mechanistic Insights of 3-Hydroxybutyrate (3-OBA) in Bladder Cancer. Molecules, 30(23), 4624. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234624