Investigation of the Photocatalytic Activity and Light-Absorbing Properties of SrTiO3/TiO2NT@S Composite

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

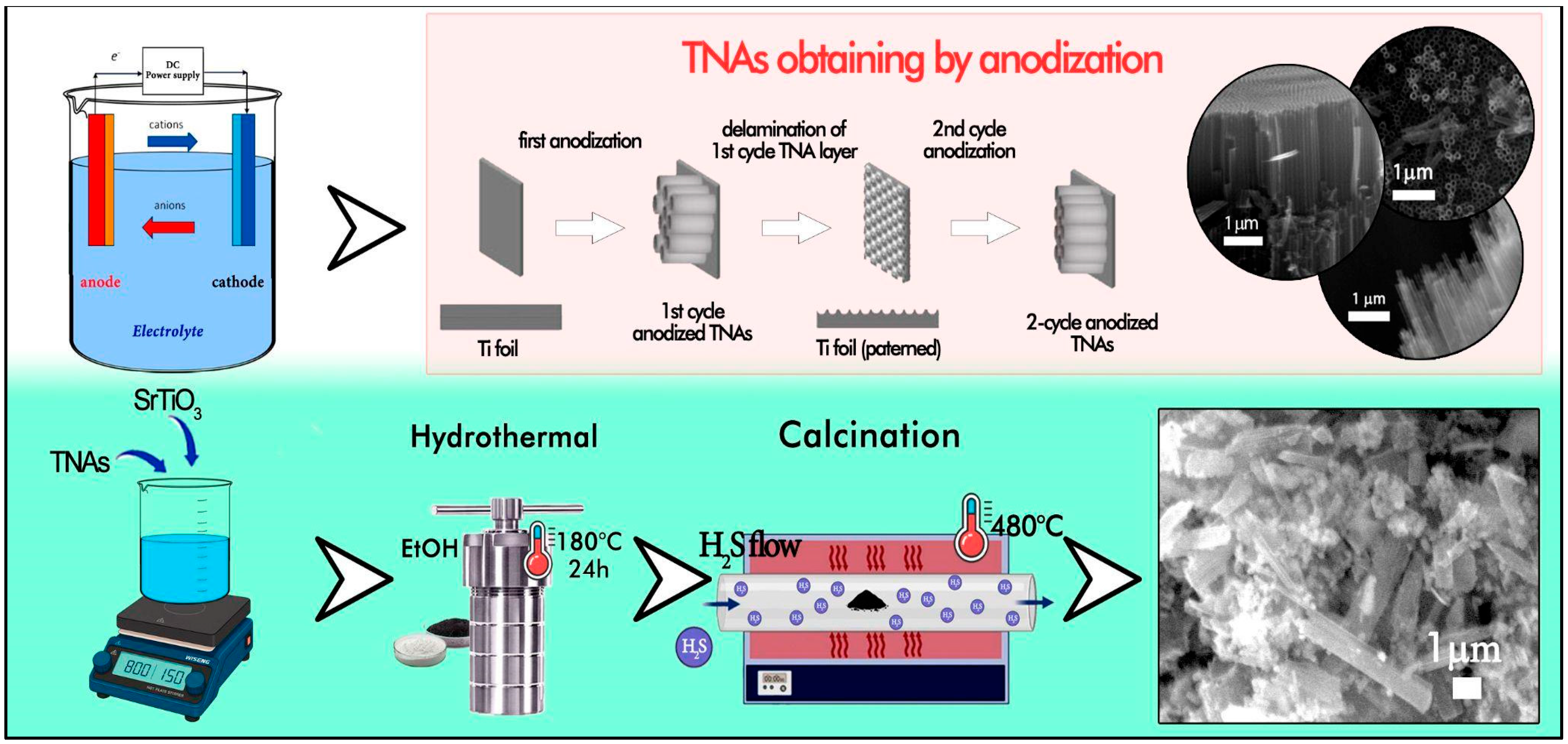

3.2. Nanotube Synthesis

3.3. Synthesis of SrTiO3/TiO2NT@S

3.4. Photocatalytic Measurements

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Riyadh, R.I.; Hossen, M.A.; Tahir, M.; Abd, A.A. A Comprehensive Review on Anodic TiO2 Nanotube Arrays (TNTAs) and Their Composite Photocatalysts for Environmental and Energy Applications: Fundamentals, Recent Advances and Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 499, 215495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Im, S.; Weon, S.; Shin, H.; Lim, J. Reduced TiO2 Nanotube Arrays as Environmental Catalysts That Enable Advanced Oxidation Processes: A Mini Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 477, 147031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Wang, J.; Xie, Q.; Li, X. Water Splitting on TiO2 Nanotube Arrays. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 9251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-García, Á.; Macià Escatllar, A.; Illas, F.; Bromley, S.T. Understanding the Interplay between Size, Morphology and Energy Gap in Photoactive TiO2 Nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 9032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, A.; Wang, X.; Wang, T.; Song, Y. TiO2 Nanotube Arrays as a Photoelectrochemical Platform for Sensitive Ag+ Ion Detection Based on a Chemical Replacement Reaction. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2023, 931, 117177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasyurek, L.B.; Isik, E.; Isik, I.; Kilinc, N. Enhancing the Performance of TiO2 Nanotube-Based Hydrogen Sensors through Crystal Structure and Metal Electrode. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 54, 678–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M.; Szkoda, M.; Sawczak, M.; Cenian, A.; Lisowska-Oleksiak, A.; Siuzdak, K. Flexible Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells Based on Ti/TiO2 Nanotubes Photoanode and Pt-Free and TCO-Free Counter Electrode System. Solid State Ionics 2017, 302, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-M.; Chen, Y.-X.; Tong, M.-H.; Lin, S.-W.; Zhou, J.-W.; Jiang, X.; Lu, C.-Z. Self-Organized TiO2 Nanotube Arrays with Controllable Geometric Parameters for Highly Efficient PEC Water Splitting. Chin. J. Struct. Chem. 2022, 41, 2202159–2202167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabzehvar, F.; Sarraf, S.; Soltanieh, M.; Seyedein, S.H. Improving Bioactivity of Anodic Titanium Oxide (ATO) Layers with Chlorine Ion Addition in Electrolytes. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 3493–3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulfah, I.M.; Fitriani, D.A.; Azahra, S.A.; Saudi, A.U.; Kozin, M.; Hanafi, R.; Puranto, P.; Damisih, B.; Sugeng, B.; Thaha, Y.N.; et al. Effect of Cathode Material on the Morphology and Osseointegration of TiO2 Nanotube Arrays by Electrochemical Anodization Technique. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 470, 129836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sun, Y.; Tian, R.; Gao, Q.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, F. Anodic Growth of TiO2 Nanotube Arrays: Effects of Substrate Curvature and Residual Stress. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 469, 129783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, T.M.; Wilson, P.; Ramesh, C.; Sagayaraj, P. A Comparative Study on the Morphological Features of Highly Ordered Titania Nanotube Arrays Prepared via Galvanostatic and Potentiostatic Modes. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2014, 14, 868–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-Y.; Mahmoud, Z.H.; Abdullaev, S.; Ali, F.K.; Naeem, Y.A.; Mizher, R.M.; Karim, M.M.; Abdulwahid, A.S.; Ahmadi, Z.; Habibzadeh, S.; et al. Nano Titanium Oxide (Nano-TiO2): A Review of Synthesis Methods, Properties, and Applications. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 9, 100626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, Y.; Gareso, P.L.; Armynah, B.; Tahir, D. A Review of TiO2 Photocatalyst for Organic Degradation and Sustainable Hydrogen Energy Production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 55, 984–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, T.; Wang, Q. Flexible CdS and PbS Nanoparticles Sensitized TiO2 Nanotube Arrays Lead to Significantly Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 28785–28791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, R.B.; Jamble, S.N.; Kale, R.B. A Review on TiO2/SnO2 Heterostructures as a Photocatalyst for the Degradation of Dyes and Organic Pollutants. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 307, 114533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collao, A.M.A.; Rovasio, V.A.; Oviedo, M.B.; Pérez, O.L.; Iglesias, R.A. Nanotubular TiO2 Films Sensitized with CdTe Quantum Dots: Stability and Adsorption Distribution. Chem. Phys. 2024, 579, 112196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondar, E.; Lebedev, I.; Fedosimova, A.; Dmitriyeva, E.; Ibraimova, S.; Nikolaev, A.; Shongalova, A.; Kemelbekova, A.; Begunov, M. The Effect of pH Solution in the Sol–Gel Process on the Formation of Fractal Structures in Thin SnO2 Films. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemelbekova, A.; Dmitrieva, E.A.; Lebedev, I.A.; Grushevskaya, E.A.; Murzalinov, D.O.; Fedosimova, A.I.; Kazhiev, Z.S.; Zhaysanbayev, Z.K.; Zhaysanbayev, Z.K.; Temiraliyev, A.T. The Effect of Deposition Technique on Formation of Transparent Conductive Coatings of SnO2. Phys. Sci. Technol. 2022, 9, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengifo-Herrera, J.A.; Osorio-Vargas, P.; Pulgarin, C. A Critical Review on N-Modified TiO2 Limits to Treat Chemical and Biological Contaminants in Water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 425, 127979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohajernia, S.; Hejazi, S.; Mazare, A.; Nguyen, N.T.; Hwang, I.; Kment, S.; Zoppellaro, G.; Tomanec, O.; Zboril, R.; Schmuki, P. Semimetallic Core–Shell TiO2 Nanotubes as a High Conductivity Scaffold and Use in Efficient 3D-RuO2 Supercapacitors. Mater. Today Energy 2017, 6, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, L. Photoelectrochemical Properties of TiO2/SrTiO3 Combined Nanotube Arrays. Ceram. Int. 2013, 39 (Suppl. S1), S633–S636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Hou, Y.; Liao, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, D.-D.; Liu, S.; Zhou, W.; Guo, L. Construction of SrTiO3/TiO2 Assembly Towards Optimized Photocatalytic Performance. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2026, 470, 116674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Yu, Y.; Yang, H.; German, L.N.; Li, Z.; Chen, J.; Yang, W.; Huang, L.; Shi, W.; Wang, L.; et al. Simultaneous Enhancement of Charge Separation and Hole Transportation in a TiO2–SrTiO3 Core–Shell Nanowire Photoelectrochemical System. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1701432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patial, S.; Hasija, V.; Raizada, P.; Singh, P.; Khan, A.A.P.; Asiri, A.M. Tunable Photocatalytic Activity of SrTiO3 for Water Splitting: Strategies and Future Scenario. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 103791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RaeisianAsl, M.; Jouybar, S.; Tafreshi, S.S.; Naji, L. Exploring the Key Features for Enhanced SrTiO3 Functionality: A Comprehensive Overview. Mater. Today Sustain. 2025, 29, 101072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, T.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, R.; Wang, C.; Zhou, F.; Li, S.; Zhao, L.; Feng, M. Regulation of Oxygen Vacancies in SrTiO3 Perovskite for Efficient Photocatalytic Nitrogen Fixation. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 902, 163865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboub, Z.; Seddik, T.; Daoudi, B.; Boukraa, A.; Behera, D.; Batouche, M.; Mukherjee, S.K. Impact of La, Ni-Doping on Structural and Electronic Properties of SrTiO3 for Photocatalytic Water Splitting. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023, 153, 110871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannachi, E.; Sayyed, M.I.; Albarzan, B.; Almuqrin, A.H.; Mahmoud, K.A. Synthesis and Study of Structural, Optical and Radiation-Protective Peculiarities of MTiO3 (M = Ba, Sr) Metatitanate Ceramics Mixed with SnO2 Oxide. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 28528–28535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, R.T.; Correa, O.V.; Pillis, M.F. Photocatalytic Activity of Undoped and Sulfur-Doped TiO2 Films Grown by MOCVD for Water Treatment under Visible Light. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 39, 3498–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, J.U.; Rehman, M.A.; Tahir, M.B.; Hussain, A.; Iqbal, T.; Sagir, M.; Usman, M.; Kebaili, I.; Alrobei, H.; Alzaid, M. Electronic and Optical Properties of Nitrogen and Sulfur Doped Strontium Titanate as Efficient Photocatalyst for Water Splitting: A DFT Study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, S.A.; Ribeiro, C.A. Comparative Run for Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalytic Activity of Anionic and Cationic S-Doped TiO2 Photocatalysts: A Case Study of Possible Sulfur Doping through Chemical Protocol. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2016, 421, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharotri, N.; Sud, D. A Greener Approach to Synthesize Visible Light Responsive Nanoporous S-Doped TiO2 with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity. New J. Chem. 2015, 39, 2217–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissenova, M.; Umirzakov, A.; Mit, K.; Mereke, A.; Yerubayev, Y.; Serik, A.; Kuspanov, Z. Synthesis and Study of SrTiO3/TiO2 Hybrid Perovskite Nanotubes by Electrochemical Anodization. Molecules 2024, 29, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghani, T.; Mujahid, M.; Mehmood, M.; Zhang, G.; Naz, S. Highly Ordered Combined Structure of Anodic TiO2 Nanotubes and TiO2 Nanoparticles Prepared by a Novel Route for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2019, 23, 1231–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Mutalib, M.; Ahmad Ludin, N.; Su’ait, M.S.; Davies, M.; Sepeai, S.; Mat Teridi, M.A.; Mohamad Noh, M.F.; Ibrahim, M.A. Performance-Enhancing Sulfur-Doped TiO2 Photoanodes for Perovskite Solar Cells. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, H.; Tian, C.; Zhang, H. In Situ Hydrothermal Synthesis of Visible Light Active Sulfur Doped TiO2 from Industrial TiOSO4 Solution. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Liu, S.; Su, K.; Jia, K. Facile Synthesis of Ti3+ Self-Doped and Sulfur-Doped TiO2 Nanotube Arrays with Enhanced Visible-Light Photoelectrochemical Performance. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 804, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pylnev, M.; Su, T.-S.; Wei, T.-C. Titania Augmented with TiI4 as Electron Transporting Layer for Perovskite Solar Cells. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 549, 149224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManamon, C.; O’Connell, J.; Delaney, P.; Rasappa, S.; Holmes, J.D.; Morris, M.A. A Facile Route to Synthesis of S-Doped TiO2 Nanoparticles for Photocatalytic Activity. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2015, 406, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.-A. SrTiO3/TiO2 Heterostructure Nanowires with Enhanced Electron–Hole Separation for Efficient Photocatalytic Activity. Front. Mater. Sci. 2019, 13, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Bang, J.H.; Tang, C.; Kamat, P.V. Tailored TiO2–SrTiO3 Heterostructure Nanotube Arrays for Improved Photoelectrochemical Performance. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olowoyo, J.O.; Kumar, M.; Jain, S.L.; Shen, S.; Zhou, Z.; Mao, S.S.; Vorontsov, A.V.; Kumar, U. Reinforced Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 to Fuel by Efficient S-TiO2: Significance of Sulfur Doping. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 17682–17695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanovska, N.I.; Manoryk, P.A.; Selyshchev, O.V.; Ermokhina, N.I.; Yaremov, P.S.; Grebennikov, V.M.; Shcherbakov, S.M.; Zahn, D.R.T. Effect of the Modification of TiO2 with Thiourea on Its Photocatalytic Activity in Doxycycline Degradation. Theor. Exp. Chem. 2020, 56, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Ni, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhai, L.; Shang, D.; Yang, T.; Yang, F.; Pan, J. Solar-Driven Bifunctional Hydrogel Evaporator: Surface-Polarized ZnIn2S4 Synergize with Photothermal Fe3O4 for Clean-Water Regeneration and Decontamination. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 376, 133988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

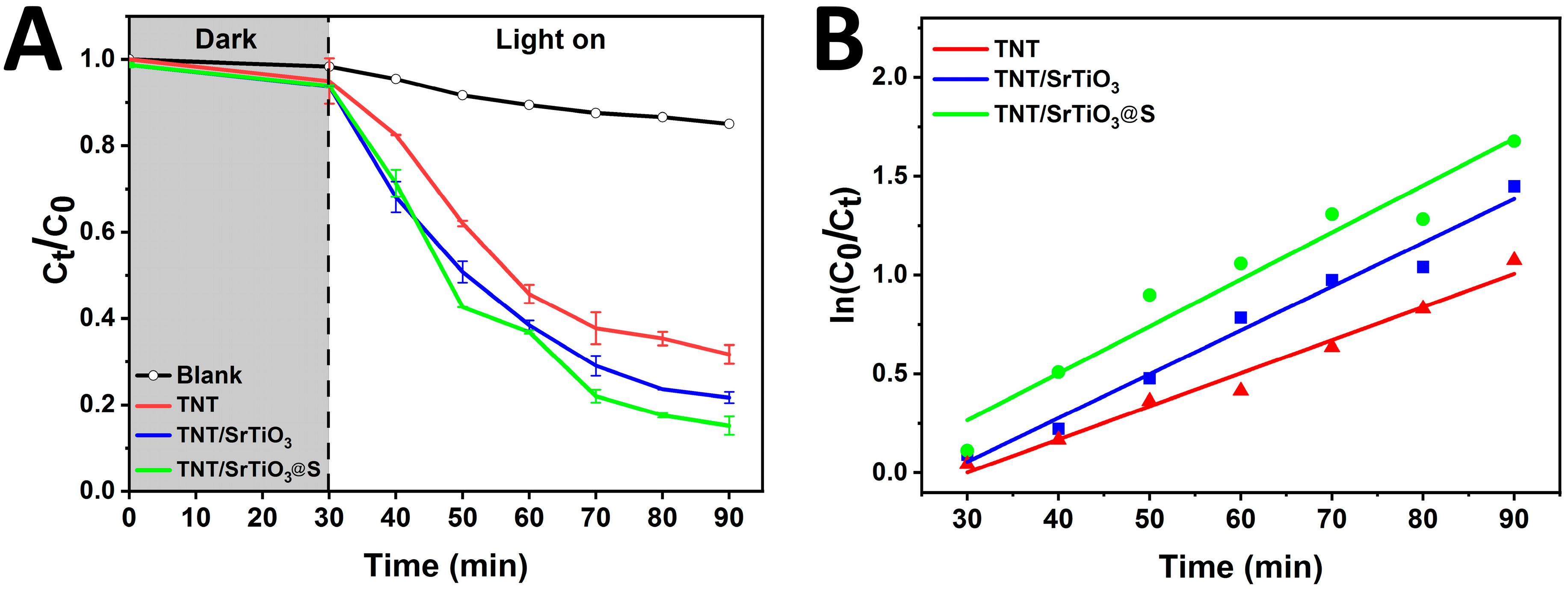

| The Sample | k, min−1 | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| TNT | 0.016 | 0.96 |

| SrTiO3/TiO2NT | 0.024 | 0.98 |

| SrTiO3/TiO2NT@S | 0.028 | 0.98 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nurlan, Y.; Chekiyeva, A.; Umirzakov, A.; Bissenova, M.; Yerubayev, Y.; Mit, K. Investigation of the Photocatalytic Activity and Light-Absorbing Properties of SrTiO3/TiO2NT@S Composite. Molecules 2025, 30, 4626. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234626

Nurlan Y, Chekiyeva A, Umirzakov A, Bissenova M, Yerubayev Y, Mit K. Investigation of the Photocatalytic Activity and Light-Absorbing Properties of SrTiO3/TiO2NT@S Composite. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4626. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234626

Chicago/Turabian StyleNurlan, Yelmira, Aruzhan Chekiyeva, Arman Umirzakov, Madina Bissenova, Yerlan Yerubayev, and Konstantine Mit. 2025. "Investigation of the Photocatalytic Activity and Light-Absorbing Properties of SrTiO3/TiO2NT@S Composite" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4626. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234626

APA StyleNurlan, Y., Chekiyeva, A., Umirzakov, A., Bissenova, M., Yerubayev, Y., & Mit, K. (2025). Investigation of the Photocatalytic Activity and Light-Absorbing Properties of SrTiO3/TiO2NT@S Composite. Molecules, 30(23), 4626. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234626