1. Introduction

Chemical modification of proteins is a key technique in bioconjugation that enables various synthetic molecules to be covalently attached to proteins. The resulting derivatized proteins serve as tools for investigating biological processes. An important modification method is cross-linking proteins by forming strong covalent bonds between specific amino acid residues within or between protein molecules. Cross-linking plays a significant role in stabilizing protein structures, maintaining tissue integrity and strength, altering protein functions, inducing pathological conditions, and facilitating interactions between proteins and between proteins and other molecules. Therefore, understanding and manipulating protein cross-linking processes is essential for elucidating biological mechanisms, developing therapeutic interventions, and engineering biomaterials with tailored properties [

1,

2,

3].

Since its definition in 2001 [

4], “click” chemistry has become an important method in modern synthetic organic chemistry encompassing various highly efficient reactions, such as nucleophilic opening of spring-loaded rings, non-aldol carbonyl chemistry, additions to C−C multiple bonds and cycloadditions. A typical “click” reaction should also be bioorthogonal, meaning it should not interact with biological systems. Among the various “click” reactions, the Cu-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) [

5,

6] emerged as the first and is now the best-known example of a “click” reaction [

7,

8,

9,

10]. In biological systems, however, CuAAC is often not truly bioorthogonal due to possible interactions of copper ions with biomolecules [

1]. This limitation was soon addressed by the introduction of a catalyst-free strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC) in 2004 [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Since then, CuAAC and SPAAC have found widespread application in connecting various types of small molecules and macromolecular entities and are now standard ligation tools in combinatorial synthesis, [

15,

16,

17] bioconjugation [

18,

19,

20,

21], and materials science [

22,

23].

Recently, we focused on applied studies aimed at labeling and covalently cross-linking native proteins using novel synthetic organic molecules as bioconjugation reagents [

24,

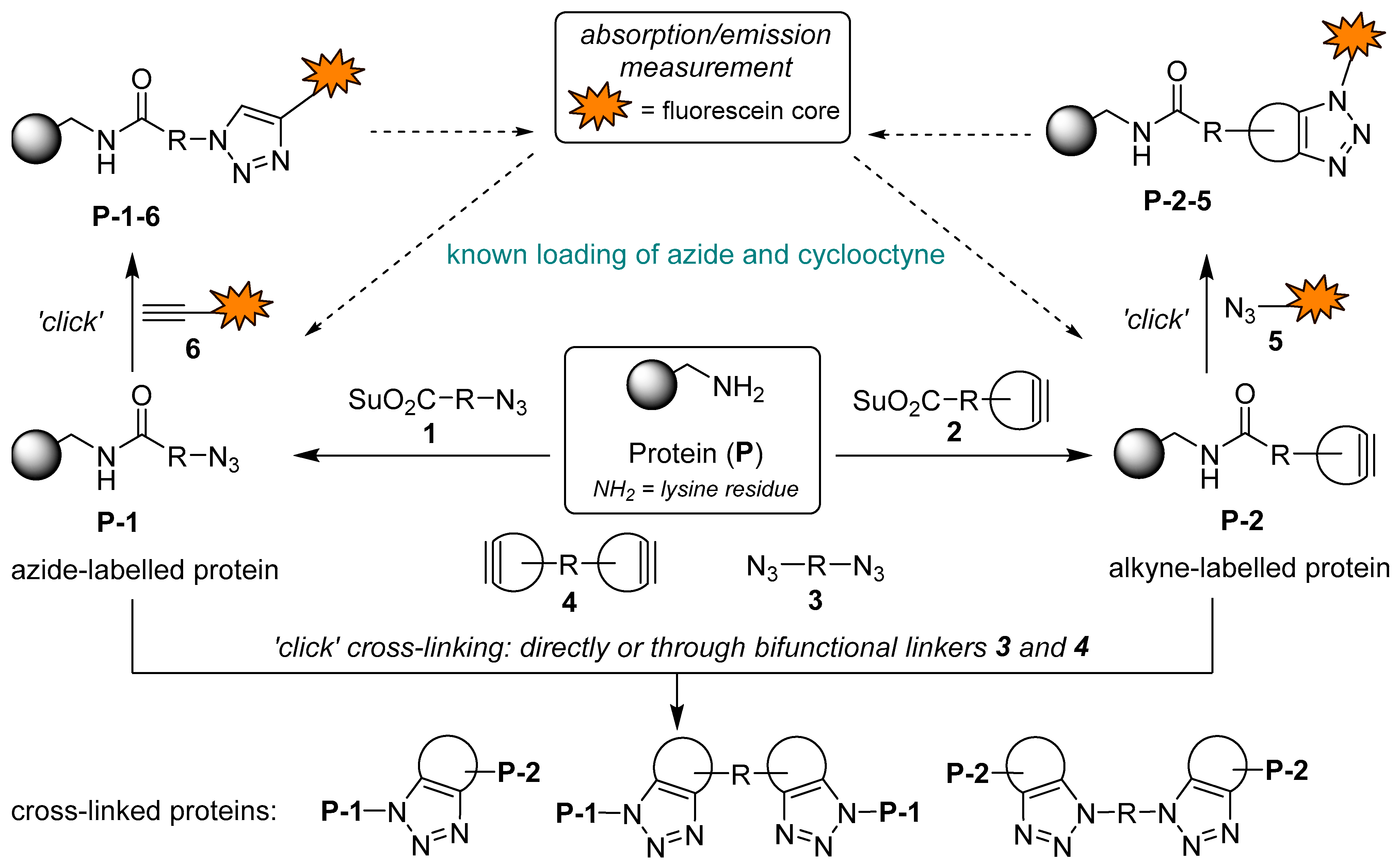

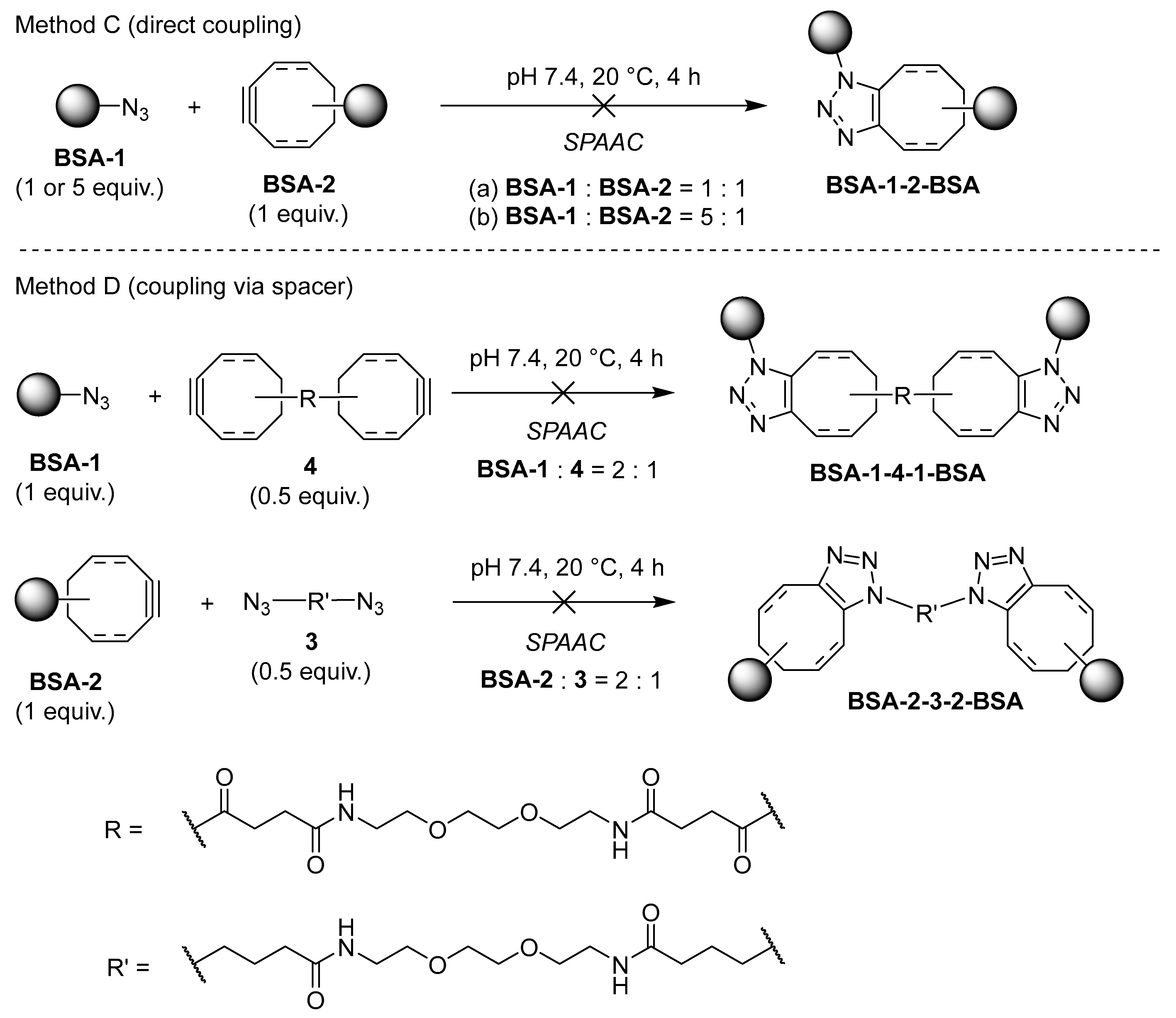

25]. The concept of linking native proteins is presented in

Figure 1. Following known protocols [

1,

2,

3], the lysine residues of a protein would be treated in parallel with excess N-acylation reagents

1 and

2 to obtain the azide-(

P-1) and cycloalkyne-functionalized proteins (

P-2). Linking these two would be achieved by SPAAC, either directly or via bifunctional spacers

3 and

4. The loading of each functional group would be determined spectrophotometrically from absorbances and/or emission intensities of fluorescently labeled proteins

P-1-6 and

P-2-5, obtained by SPAAC or CuAAC reactions between azide- and alkyne-functionalized proteins

P-1 and

P-2 and their complementary functionalized fluorescein derivatives

5 and

6. With optimal reaction conditions to achieve the desired functional group loading FG/P ~1, the proteins

P-1 and

P-2 could then be used in “click” cross-linking experiments (

Figure 1).

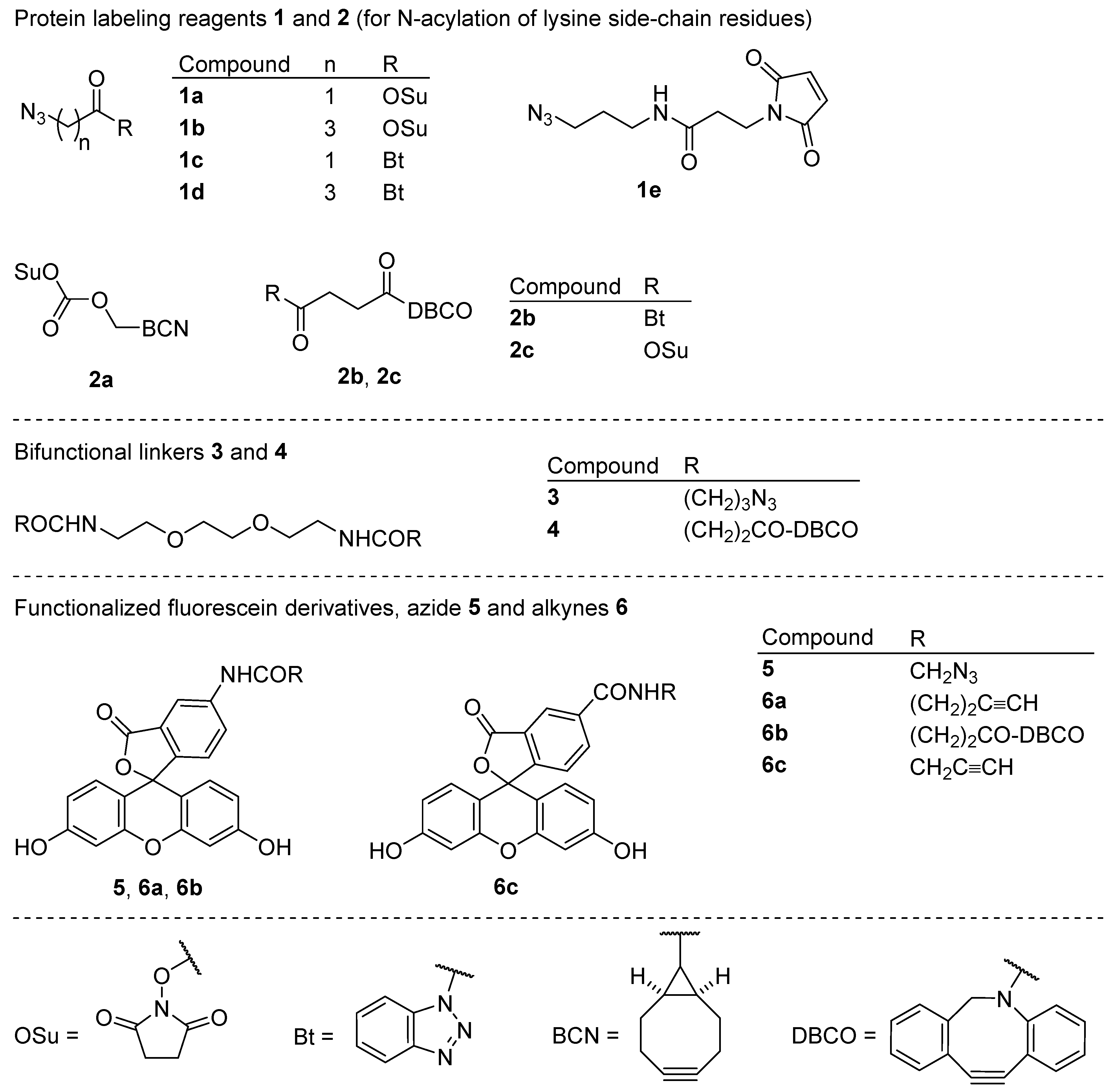

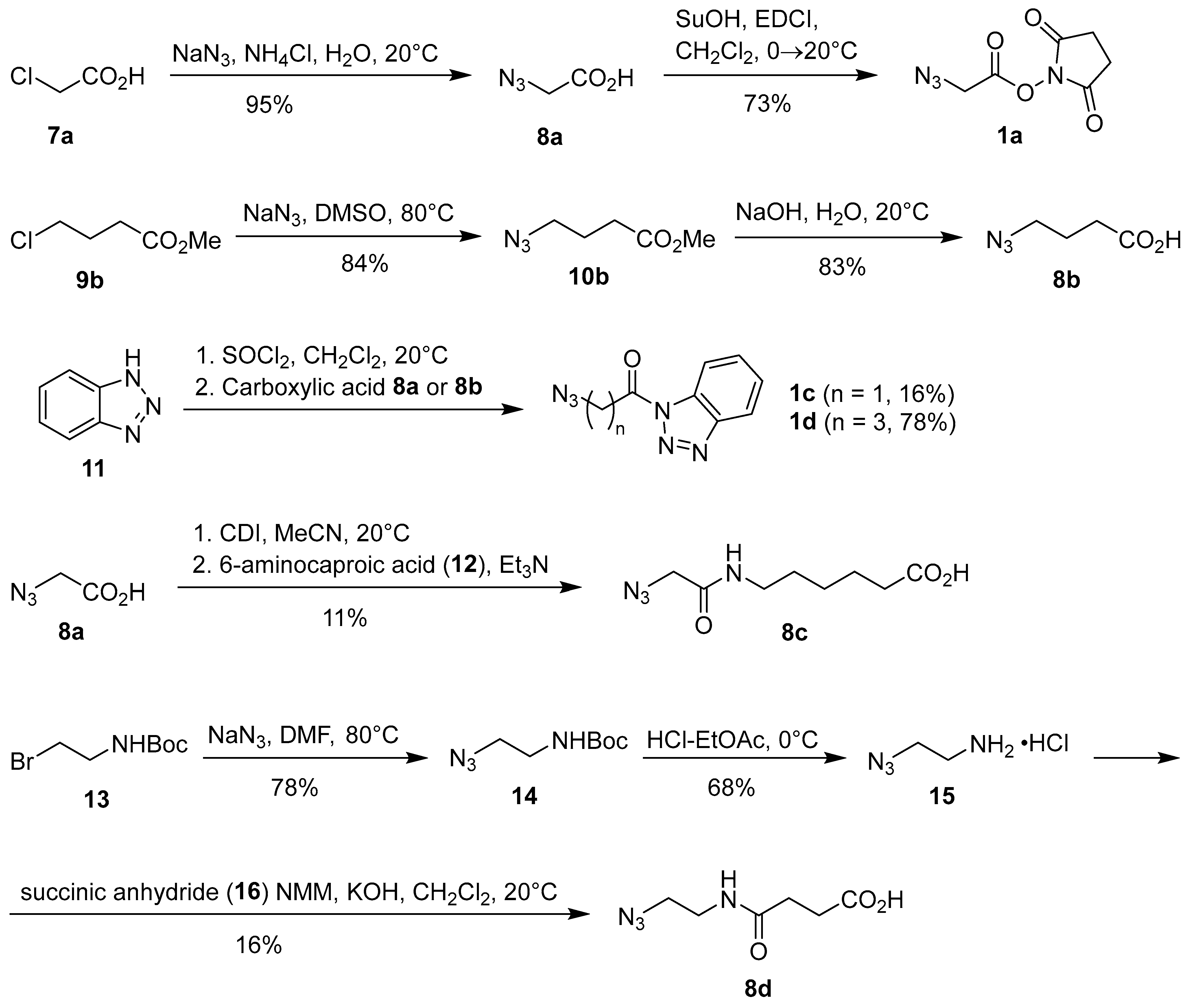

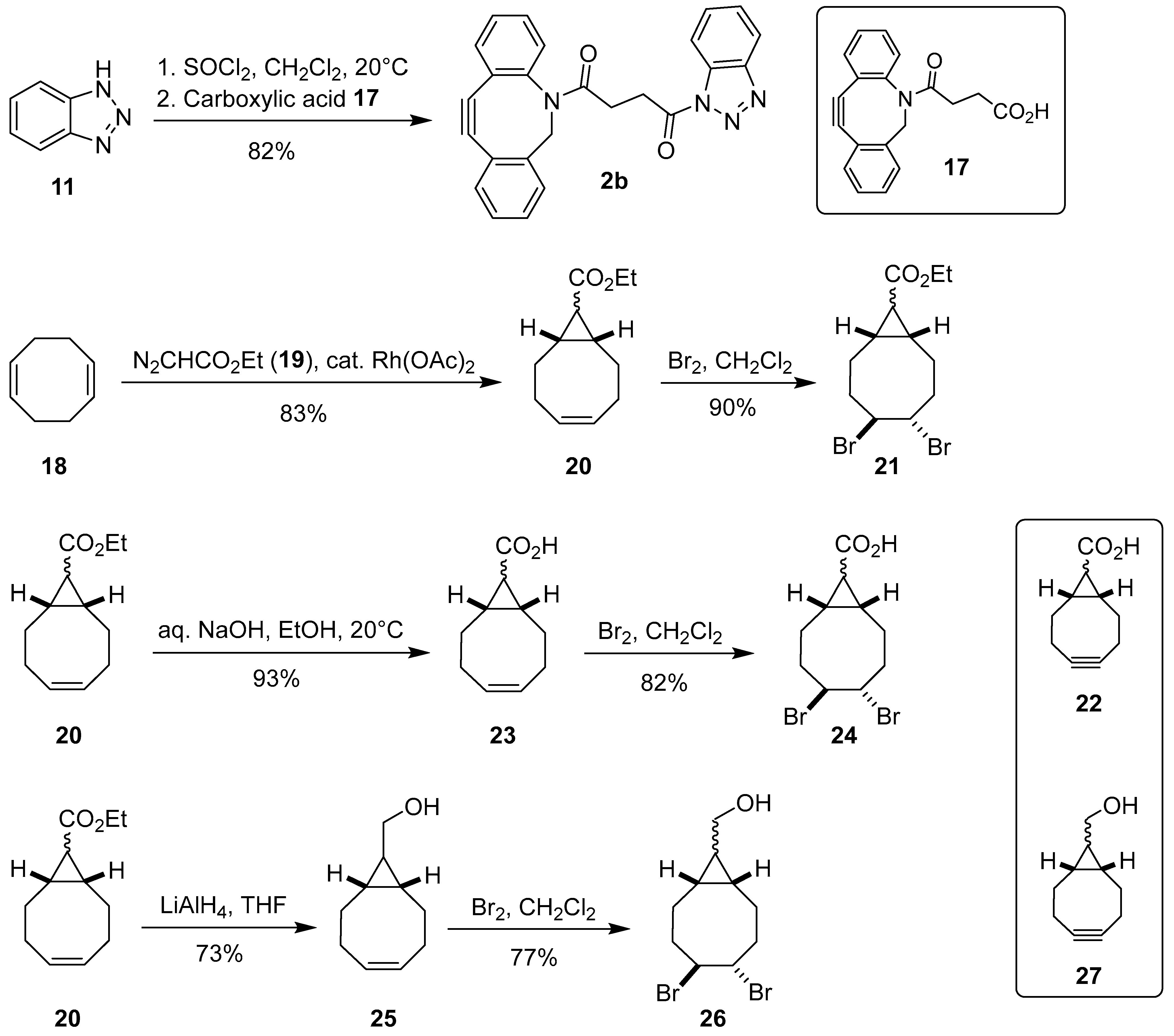

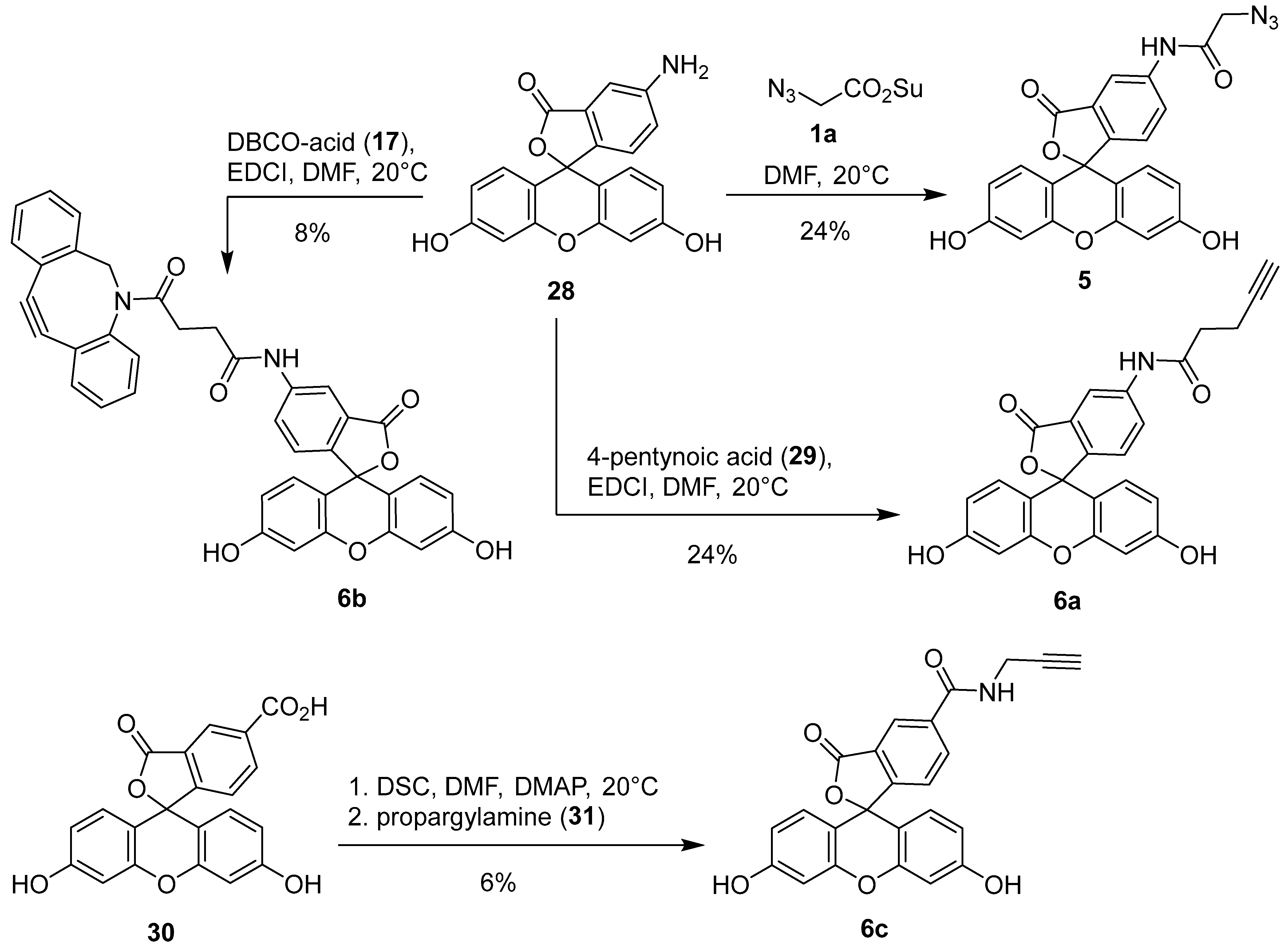

Contrary to our expectations, synthesizing both novel and known reagents proved challenging despite the extensive literature coverage on the subject. Therefore, we report the results of the first part of our ongoing study, the synthesis of a series of azide- and alkyne-functionalized bioconjugation reagents, fluorescent probes, and bifunctional linkers, as well as their application in the covalent cross-linking of bovine serum albumin (BSA).

3. Experimental

3.1. General Methods

Melting points were determined on a Kofler micro hot stage and on a Mettler Toledo MP30 automated melting point system (Mettler Toledo, Columbus, OH, USA). The NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 and DMSO-d6 using Me4Si as the internal standard on a Bruker Avance III Ultrashield 500 and Bruker Avance Neo 600 instruments (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) at 500 and 600 MHz for 1H and at 125 and 150 MHz for 13C nucleus, respectively. Chemical shifts (δ) are given in ppm relative to Me4Si as internal standard (δ = 0 ppm) and vicinal coupling constants (J) are given in hertz (Hz). HRMS spectra were recorded on an Agilent 6224 time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometer equipped with a double orthogonal electrospray source under atmospheric pressure ionization (ESI) coupled to an Agilent 1260 high-performance liquid chromatograph (HPLC) (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). UV-vis spectra were recorded in MeOH using a Varian Cary Bio50 UV-Visible Spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Emission spectra were recorded on a PerkinElmer LS 50 B Luminescence spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were obtained on a Bruker FTIR Alpha Platinum spectrophotometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) using the attenuated total reflection (ATR) sampling technique. Microanalyses for C, H, and N were obtained on a Perkin-Elmer CHNS/O Analyzer 2400 Series II (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Column chromatography (CC) was performed on silica gel (Silica gel 60, particle size: 0.035–0.070 mm (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Acquisition and analysis of gels obtained after SDS-PAGE analysis and subsequent staining were performed on a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MO Imaging System using BioRad Image Lab 6.1 Software for Windows (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Unless otherwise stated, solutions in PBS buffer (10 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM KH2PO4, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.4) were used. Prior to use, the commercial BSA was purified by loading the sample onto a HiLoad Superdex 200 pg preparative SEC column (Cytiva) connected to an ÄKTA FPLC system. The column was equilibrated in PBS buffer, pH 7.4, and a flow rate of 1 mL·min−1 was used to separate proteins. Proteins eluting at volumes corresponding to monomeric BSA were collected and stored at −80 °C until further use.

Ascorbic acid, bis(2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl) carbonate (DSC), bromine,

t-BuOK,

t-BuONa, 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole (CDI), copper(II) sulfate,

N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-

N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDCI), 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP),

N-hydroxysuccinimide, LiAlH

4, lithium diisopropylamide (LDA),

N-methylmorpholine (NMM), sodium azide, Rh(OAc)

2, thionyl chloride, tris[(1-benzyl-4-triazolyl)methyl]amine (TBTA), tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP), bovine serum albumin (

BSA), 2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl 2-azidoacetate (

1a), 2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl 4-azidobutanoate (

1b),

N-(3-azidopropyl)-3-(2,5-dioxo-2,5-dihydro-1

H-pyrrol-1-yl)propanamide (

1e), [(bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-yn-9-yl)methyl] (2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl) carbonate (

2a), 2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl 4-(11,12-didehydrodibenzo[

b,f]azocin-5(6

H)-yl)-4-oxobutanoate (

2c), chloroacetic acid (

7a), azidoacetic acid (

8a), methyl 4-chlorobutyrate (

9b), 1

H-benzo[

d][

1,

2,

3]triazole (

11), 6-aminocaproic acid (

12),

tert-butyl (2-bromoethyl)carbamate (

13), succinic anhydride (

16), 4-(11,12-didehydrodibenzo[

b,f]azocin-5(6

H)-yl)-4-oxobutanoic acid (

17),

Z,

Z-1,5-cyclooctadiene (

18), ethyl diazoacetate (

19), 6-aminofluorescein (

28), 4-pentynoic acid (

29), 6-carboxyfluorescein (

30), propargylamine (

31), 2,2′-[ethane-1,2-diylbis(oxy)]bis(ethan-1-amine) (

32), adipoyl chloride (

33), and 1,4-diisothiocyanatobutane (

35) are commercially available.

2,5-Dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl 2-azidoacetate (

1a) [

26], 3′,6′-dihydroxy-3-oxo-

N-(prop-2-yn-1-yl)-3

H-spiro[isobenzofuran-1,9′-xanthene]-6-carboxamide (

6c) [

36,

37], azidoacetic acid (

8a) [

38], 4-azidobutanoic acid (

8b), methyl 4-azidobutanoate (

10b) [

39], and

tert-butyl (2-azidoethyl)carbamate (

14) [

42,

43] were prepared following the literature procedures (see experimental procedures for the references).

Unless otherwise stated, solutions in PBS buffer (10 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM KH2PO4, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.4) were used.

3.2. 2-Azidoacetic Acid (8a) [38]

This compound was prepared following a slightly modified general literature procedure for the synthesis of alkyl azides [

38]. NaN

3 (672 mg, 10.5 mmol) and ammonium chloride (1.06 g, 20 mmol) were added to a solution of chloroacetic acid (

7a) (945 mg, 10 mmol) in water (7 mL) and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 72 h. The reaction mixture was acidified with aq. HCl to pH 2 and the product was extracted with Et

2O (3 × 20 mL). The combined organic phases were dried over anh. MgSO

4, filtered, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo to give

8a. Yield: 957 g (95%) of colorless oil.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl

3) δ 9.09 (br s, 1H), 4.14 (s, 2H). Spectral data are in agreement with the literature data [

26,

38].

3.3. 2,5-Dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl 2-Azidoacetate (1a) [26]

This compound was prepared following the literature procedure [

26]. The reaction was carried out under argon. A mixture of azidoacetic acid (

8) (508 g, 5 mmol),

N-hydroxysuccinimide (862 g, 7.5 mmol), and anh. CH

2Cl

2 (15 mL) was stirred at 0 °C for 10 min. Then,

N-[3-(dimethylamino)propyl]-

N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDCI) (1.438 g, 7.5 mmol) was added and stirring continued for another 10 min at 0 °C and then at room temperature for 24 h. The organic phase was washed with water (2 × 5 mL) and brine (5 mL), then dried over anh. Na

2SO

4, filtered, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo to give

1a. Yield: 729 mg (73%) of white solid.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl

3) δ 4.24 (s, 2H), 2.87 (s, 4H). Spectral data are in agreement with the literature data [

26].

3.4. Synthesis of Methyl 4-Azidobutanoate (10b) [39]

This compound was prepared following a slightly modified literature procedure [

39]. Methyl 4-chlorobutanoate (

9b) (609 μL, 682 mg, 5 mmol) was dissolved in DMSO (5 mL), NaN

3 (975 mg, 15 mmol) was added, and the mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 12 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature, diluted with Et

2O (20 mL), and washed with water (3 × 10 mL). The organic phase was dried over anh. MgSO

4, filtered, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo to give

10b. Yield: 603 mg (84%) of yellowish oil.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl

3) δ 3.69 (s, 3H), 3.35 (t,

J= 6.7 Hz, 2H), 2.42 (t,

J= 7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.91 (pentet,

J= 7.0 Hz, 2H). ν

max (ATR) 2093 (N

3), 1732 (C=O), 1437, 1164, 1080, 897 cm

−1. Spectral data are in agreement with the literature data [

39].

3.5. Synthesis of 4-Azidobutanoic Acid (8b) [39]

This compound was prepared following a modified literature procedure [

39]. Methyl 4-azidobutanoate (

10b) (603 mg, 4.2 mmol) was dissolved in MeOH (3 mL), 2 M aq. NaOH (4.2 mL, 8.4 mmol) was added and the mixture was stirred at 20 °C for 1 h. The reaction mixture was acidified with 1 M aq. HCl to pH 1, and the product was extracted with Et

2O (3 × 20 mL). The combined organic phase was dried over anh. MgSO

4, filtered, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo to give

8b. Yield: 460 mg (83%) of yellowish oil.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl

3) δ 11.13 (br s, 1H), 3.38 (t,

J= 6.7 Hz, 2H), 2.48 (t,

J= 7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.92 (pentet,

J= 7.0 Hz, 2H). Spectral data are in agreement with the literature data [

39].

3.6. General Procedure for the Synthesis of N-Acylbenzotriazoles 1c, 1d, and 2b

Compounds

1c,

1d, and

2b were prepared following the general literature procedure for the preparation of

N-acylbenzotriazoles [

41]. Under Ar, SOCl

2 (150 µL, 2 mmol) was slowly added via syringe to a stirred solution of 1

H-benzotriazole (1.00 g, 8 mmol) in anh. CH

2Cl

2 (50 mL) at r.t. and the mixture was stirred at r.t. for 30 min. Then, carboxylic acid

8a,

8b, or

17 (2 mmol) was added and a white precipitate that was formed within a few seconds was collected by filtration and washed with CH

2Cl

2 (2 × 10 mL). The combined filtrate was washed with 2 M aq. NaOH (30 mL), dried over anh. Na

2SO

4, filtered, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo to give

1c,

1d, and

2c.

3.6.1. 2-Azido-1-(1H-benzo[d][1,2,3]triazol-1-yl)ethan-1-one (1c) [28]

From 1H-benzo[d][1,2,3]triazole (11) (4.617 g, 38.8 mmol), SOCl2 (688 μL, 9.7 mmol), azidoacetic acid (8a) (980 mg, 9.7 mmol), the precipitate was washed with CH2Cl2 (2 × 50 mL), and the combined filtrate with 2 M aq. NaOH (3 × 60 mL). Yield: 322 mg (16%) of yellow solid, m.p. 56–64 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.30 (ddt, J = 8.4, 4.2, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 8.17 (dt, J = 8.4, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (ddt, J = 8.3, 7.0, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (ddt, J = 8.1, 7.4, 0.9 Hz, 1H), and 5.20 and 5.02 (2s, 1:2, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 172.3, 138.5, 126.7, 115.0, 50.4. m/z (HRMS) Found: 120.0509 [MH–N3CH2CO]+. C6H6N3 requires m/z = 120.0556. νmax (ATR) 2953, 2108, 1723 (C=O), 1413, 1278, 1202, 1012, 778, 737, 688 cm−1.

3.6.2. 4-Azido-1-(1H-benzo[d][1,2,3]triazol-1-yl)butan-1-one (1d)

From 1H-benzo[d][1,2,3]triazole (11) (1.67 g, 14 mmol), SOCl2 (247 μL, 3.5 mmol), 4-azidobutanoic acid (8b) (452 mg, 3.5 mmol), the precipitate was washed with CH2Cl2 (2 × 15 mL), and the combined filtrate with 2M aq. NaOH (3 × 20 mL). Yield: 625 mg (78%) of yellow solid, m.p. 48–50 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.28 (br d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (br d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (ddd, J = 8.1, 7.1, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (ddd, J = 8.1, 7.0, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 3.55 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.53 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), and 2.20 (pentet, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 171.6, 146.3, 131.1, 130.6, 126.4, 120.3, 114.4, 50.6, 32.7, 23.7. m/z (HRMS) Found: 253.0813 [M + Na]+. C10H10N6NaO requires m/z = 253.0808. Anal. Calcd. for C10H10N6O: C, 52.17; H, 4.38; N, 36.50%. Found: C, 52.20; H, 4.12; N, 36.26%. νmax (ATR) 2099, 1742 (C=O), 1485, 1445, 1365, 1287, 1260, 1165, 1065, 1003, 966, 854, 771, 755, 630 cm−1.

3.6.3. N-[4-(11,12-Didehydro-5,6-dihydrodibenzo[b,f]azocin-5-yl)-4-oxobutanoyl]-1H-benzo[d][1,2,3]triazole (2b)

From 1H-benzo[d][1,2,3]triazole (11) (714 mg, 6 mmol), SOCl2 (106 μL, 1.5 mmol)), DBCO-acid (17) (457 mg, 1.5 mmol), the precipitate was washed with CH2Cl2 (2 × 5 mL), and the combined filtrate with 2M aq. NaOH (3 × 6 mL). Yield: 500 mg (82%) of pink solid, m.p. 160–163 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.20 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (dd, J = 8.3, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 7.72–7.57 (m, 3H), 7.51–7.40 (m, 4H), 7.37–7.24 (m, 3H), 5.20 (d, J = 13.9 Hz, 1H), 3.80 (ddd, J = 18.4, 9.0, 5.1 Hz, 1H), 3.73 (d, J = 13.9 Hz, 1H), 3.38 (ddd, J = 18.4, 6.0, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.06 (ddd, J = 16.9, 9.0, 5.1 Hz, 1H), and 2.20 (dt, J = 17.0, 5.6 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.6, 171.2, 151.4, 147.9, 146.0, 132.1, 131.0, 130.2, 129.3, 128.6, 128.3, 127.8, 127.2, 126.0, 125.5, 123.1, 122.8, 120.1, 115.1, 114.3, 107.6, 55.6, 53.5, 30.9, 28.6. m/z (HRMS) Found: 407.1491 [M + H]+. C25H19N4O2 requires m/z = 407.1491. νmax (ATR) 1727, 1652, 1479, 1448, 1387, 1350, 1307, 1226, 1165, 1063, 1005, 960, 802, 780, 765, 751, 649, 634 cm−1.

3.7. Synthesis of 6-(2-Azidoacetamido)hexanoic Acid (8c)

Under argon, CDI (2.00 g, 12.3 mmol) was added to a stirred solution of azidoacetic acid (8a) (1.22 g, 12.1 mmol) in anh. MeCN (30 mL) and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. Then, 6-aminocaproic acid (12) (1.75 g, 13.3 mmol) was added and stirring under argon was continued for 2 h at room temperature and then for 24 h at 40 °C. Volatile components were evaporated in vacuo, the residue was dissolved in water (15 mL) and acidified with 1 M aq. HCl to pH 1, and the product was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 70 mL). The combined organic phase was dried over anh. Na2SO4, filtered, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo to give 8c. Yield: 290 mg (11%) of yellow oil. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.23 (s, 1H), 8.19, 8.08, and 7.72 (3br t, 3:1:1, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 4.27, 4.02, 3.99, and 3.78 (4s, 3:6:1:2, 2H), 3.06 and 3.00 (2q, 4:1, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.19 and 2.02 (2t, 5:1, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 1.52–1.45 (m, 2H), 1.44–1.34 (m, 2H), 1.29–1.17 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 174.9, 172.5, 172.3, 170.6, 169.1, 167.5, 166.2, 51.2, 49.9, 43.1, 42.0, 35.8, 34.0, 29.4, 29.1, 29.0, 26.4, 26.3, 25.5, 24.6, 21.5. Multiple signals for all nuclei are due to the presence of isomers (rotamers). m/z (HRMS) Found: 213.1003 [M − H]−. C8H15N4O3 requires m/z = 213.0993. νmax (ATR) 2937, 2109 (N3), 1708 (C=O), 1631 (C=O), 1545, 1411, 1194, 1102, 927, 789, 639 cm−1.

3.8. Synthesis of tert-Butyl (2-Azidoethyl)carbamate (14) [42,43]

Compound

14 was prepared following a slightly modified literature procedure [

42,

43]. A mixture of

tert-butyl (2-bromoethyl)carbamate (

13) (1.12 g, 5 mmol), sodium azide (357 mg, 5.5 mmol), and anh. DMF (10 mL) was stirred under argon at 80 °C for 12 h. The mixture was cooled to room temperature, Et

2O (50 mL) was added, and the solution was washed with brine (5 × 10 mL). The organic phase was evaporated in vacuo to give

14. Yield: 723 mg (78%) of colorless oil.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl

3) δ 4.89 (br s, 1H), 3.39 (t,

J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 3.28 (q,

J = 5.9 Hz, 2H), 1.43 (s, 9H). ν

max (ATR) 3349, 2978, 2933, 2095 (N

3), 1687 (C=O), 1511, 1451, 1391, 1366, 1247, 1162, 1099, 1039, 992, 861, 781, 758, 637. cm

−1. Spectral data are in agreement with the literature data [

42,

43].

3.9. 2-Azidoethan-1-aminium Chloride (15) [44]

Compound

15 was prepared following a modified literature procedure [

44]. Compound

14 (723 mg, 3.88 mmol) was dissolved in EtOAc (6 mL) and cooled to 0 °C (ice-bath). While stirring at 0 °C, 2 M HCl (6 mL, 12 mmol) was added and stirring at 0 °C was continued for 2.5 h. The precipitate was collected by filtration, washed with EtOAc (2× 5 mL), and dried over NaOH pellets in vacuo at room temperature for 24 h to give

14. Yield: 250 mg (68%) of white solid.

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-

d6) δ 8.26 (br s, 3H), 3.75–3.55 (m, 2H), 2.95 (dd,

J = 6.6, 5.0 Hz, 2H). Spectral data are in agreement with the literature data [

44,

45].

3.10. Synthesis of 4-[(2-Azidoethyl)amino]-4-oxobutanoic Acid (8d) [46]

This compound was prepared following a modified literature procedure [

46]. Succinic anhydride (

16) (50 mg, 0.5 mmol) and

N-methylmorpholine (NMM) (110 μL, 1 mmol) were added to a stirred suspension of compound

15 (60 mg, 0.5 mmol) in a mixture of anh. CH

2Cl

2 (1 mL) and anh. THF (1 mL) for 1 h at room temperature. KOH (28 mg, 0.5 mmol) was added and stirring at room teperature was continued for 24 h. Then, CH

2Cl

2 (10 mL) was added and the mixture was washed with 1 M aq. HCl (5 mL) and brine (2 × 5 mL). The organic phase was dried over anh. MgSO

4, filtered, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo to give

8d. Yield: 15 mg (16%) of yellow resin.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl

3) δ 6.01 (br s, 1H), 3.49–3.41 (m, 4H), 2.73 (dd,

J = 7.3, 5.7 Hz, 2H), 2.53 (dd,

J = 7.3, 5.7 Hz, 2H). Spectral data are in agreement with the literature data [

46].

3.11. Synthesis of Ethyl (1R*,8S*,4Z)-Bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-ene-9-carboxylate (20) [47]

This compound was prepared following the literature procedure [

47]. A solution of ethyl diazoacetate (2.1 mL, 20 mmol) in CH

2Cl

2 (10 mL) was added slowly (dropwise over ~1 h) to a stirred mixture of

Z,

Z-1,5-cyclooctadiene (19.6 mL, 160 mmol), Rh(OAc)

4 (380 mg, 0.86 mmol), and CH

2Cl

2 (10 mL) and the mixture was stirred at r.t. for 40 h. Insoluble material was removed by filtration through a glass frit and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo. The residue was purified by CC (silica gel, petroleum ether). Fractions containing the product were combined and evaporated in vacuo to afford

20 as a C(9)-

endo/

exo-mixture of epimers. Yield: 3.22 g (83%) of colorless oil.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl

3) δ 5.63 and 5.60 (dq and td, 3:2,

J = 4.1, 2.1 and 4.0, 2.3 Hz, 2H), 4.11 and 4.09 (2q, 2:3,

J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.50 and 2.30 (2 ddt, 2:3,

J = 15.8, 8.0, 3.7 and 15.1, 7.6, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 2.24–2.15 (m, 2H), 2.12–2.01 (m, 2H), 1.82 (dddd,

J = 14.4, 9.8, 7.1, 5.1 Hz, 1H), 1.71 and 1.18 (2t, 3:3,

J = 8.8 and 4.6 Hz, 1H), 1.59–1.53 (m, 1H), 1.52–1.43 (m, 1H), 1.42–1.36 (m, 1H), 1.28–1.23 (m, 4H). Spectral data are in agreement with the literature data [

47,

53].

3.12. Synthesis of Ethyl (1R*,4R*,5R*,8S*)-4,5-Dibromobicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-ene-9-carboxylate (21) [48]

A solution of Br

2 (320 mg, 2 mmol) in CH

2Cl

2 (2 mL) was added to a stirred solution of

20 (388 mg, 2 mmol) in CH

2Cl

2 (20 mL) and the solution was stirred at room temperature for 15 min. Then, the reaction was quenched by the addition of 10% aq. Na

2S

2O

3 (5 mL). The phases were separated and the aqueous phase was extracted with CH

2Cl

2 (2 × 10 mL). The combined organic phase was dried over anh. MgSO

4, filtered, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo to give

21 as a mixture of isomers. Yield: 642 mg (90%) of yellow resin.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl

3) δ 4.87–4.81 (m, 1H), 4.80–4.75 (m, 1H), 4.12 and 4.11 (2 q, 1:1,

J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.77–2.68 and 2.68–2.60 (2 m, 3:2, 2H), 2.37–2.24 (m, 2H), 2.23–2.06 (m, 2H), 1.88–1.60 (m, 3H), 1.53–1.37 (m, 1H), 1.29–1.18 (m, 4H). Spectral data are in agreement with the literature data [

48].

3.13. Synthesis of (1R*,8S*,4Z)-Bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-ene-9-carboxylic Acid (23) [49,50]

A 2 M aq. NaOH (2 mL, 4 mmol) was added to a solution of

20 (136 mg, 0.7 mmol) in EtOH (3 mL), the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 h, and acidified with 1 M aq. HCl to pH 2. The product was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 20 mL), the organic phases were combined, dried over anh. Na

2SO

4, filtered, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo to give

23 as a C(9)-

endo/

exo-mixture of epimers. Yield: 108 mg (93%) of colorless oil.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl

3) δ 11.77 (s, 1H), 5.60–5.54 (m, 2H), 2.42–2.34 (m, 1H), 2.29–2.21 (m, 1H), 2.14–2.06 (m, 2H), 2.06–1.95 (m, 2H), 1.79–1.70 (m, 1H), 1.59 and 1.14 (2 t, 1:2,

J = 8.7 and 4.6 Hz, 1H), 1.52–1.42 (m, 1H), 1.41–1.29 (m, 2H). Spectral data are in agreement with the literature data [

49,

50].

3.14. Synthesis of (1R*,4R*,5R*,8S*)-4,5-Dibromobicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-ene-9-carboxylic Acid (24) [51,52]

This compound was prepared following a modified literature procedure [

52]. A solution of Br

2 (431 mg, 2.7 mmol) in CH

2Cl

2 (2 mL) was added to a stirred solution of

23 (450 mg, 2.7 mmol) in CH

2Cl

2 (20 mL) and the solution was stirred at room temperature for 15 min. Then, the reaction was quenched by the addition of 10% aq. Na

2S

2O

3 (5 mL). The phases were separated and the aqueous phase was extracted with CH

2Cl

2 (2 × 10 mL). The combined organic phase was dried over anh. MgSO

4, filtered, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo to give

24 as a mixture of isomers. Yield: 720 mg (82%) of colorless resin.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl

3) δ 11.92 (br s, 1H), 5.04–4.92 (m, 2H), 2.64–2.51 (m, 2H), 2.24–2.09 (m, 2H), 2.08–1.99 (m, 2H), 1.78–1.61 (m, 1H), 1.69 and 1.17 (2 t, 2:3,

J = 8.7 and 4.1 Hz, 1H), 1.52–1.30 (m, 3H). Spectral data are in agreement with the literature data [

51,

52].

3.15. Synthesis of [(1R*,8S*,9RS,4Z)-Bicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl]methanol (25) [47]

This compound was prepared following the literature procedure [

47]. Reaction was carried out under argon in a flame-dried flask. A solution of LiAlH

4 in anh. THF (2.4 M, 500 μL, 1.2 mmol) was added via syringe to a stirred cold (0 °C, ice-bath) solution of

20 (194 mg, 1 mmol) in anh. Et

2O (2 mL) and the mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 15 min and then at 45 °C for 1 h. The mixture was cooled to 0 °C and the reaction was quenched by slow (dropwise) addition of water (3 mL) to the stirred mixture. The obtained solution was diluted with THF (20 mL), dried over anh. Na

2SO

4, filtered, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo to give

25. Yield: 111 mg (73%) of pale yellow resin.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl

3) δ 5.63 (td,

J = 4.2, 2.1 Hz, 2H), 3.71 (d,

J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 3.47 (d,

J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 2.45–2.24 (m, 2H), 2.22–1.93 (m, 4H), 1.91–1.70 (m, 1H), 1.57 (m, 1H), 1.47–1.32 (m, 1H), 1.29–1.06 (m, 1H), 1.05–0.97 (m, 1H), 0.80–0.63 (m, 1H). Spectral data are in agreement with the literature data [

47].

3.16. Synthesis of [(1R*,4R*,5R*,8S*,9RS)-4,5-Dibromobicyclo[6.1.0]non-4-en-9-yl]methanol (26) [47,53]

This compound was prepared following the literature procedure [

47]. A solution of Br

2 (37 μL, 115 mg, 0.73 mmol) in CH

2Cl

2 (2 mL) was added to a stirred solution of

25 (111 mg, 0.7 mmol) in CH

2Cl

2 (5 mL) and the solution was stirred at room temperature for 15 min. Then, the reaction was quenched by the addition of 10% aq. Na

2S

2O

3 (5 mL). The phases were separated and the aqueous phase was extracted with CH

2Cl

2 (2 × 10 mL). The combined organic phase was dried over anh. MgSO

4, filtered, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo to give

25. Yield: 167 mg (77%) of yellowish resin.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl

3) δ 4.89–4.69 (m, 2H), 3.76 (dd,

J = 7.5, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 3.52 (dd,

J = 7.1, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 2.79–2.56 (m, 2H), 2.36–1.84 (m, 4H), 1.70–1.52 (m, 2H), 1.48–1.31 (m, 1H), 1.30–1.03 (m, 1H), 1.00–0.81 (m, 1H), 0.68 (m, 1H). Spectral data are in agreement with the literature data [

47,

53].

3.17. 2-Azido-N-(3′,6′-dihydroxy-3-oxo-3H-spiro[isobenzofuran-1,9′-xanthen]-6-yl)acetamide (5) [33,34]

NHS azidoacetate

1a (99 mg, 0.5 mmol) was added to a stirred solution of

28 (174 mg, 0.5 mmol) in MeCN (3 mL) and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. EtOAc (15 mL) was added, and the solution was washed with 1 M aq. NaHSO

4 (5 mL) and brine (5 mL). The organic phase was dried over anh. MgSO

4, filtered, and evaporated in vacuo. The residue (crude compound

5, 165 mg) was suspended in CH

2Cl

2 (100 mL) and stirred at room temperature for 2 h. Then, stirring was stopped and the suspension was left to settle down. The supernatant was decanted and the solid residue was dried in vacuo at room temperature to give

5. Yield: 52 mg (24%)(G.P.B) of brown solid.

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d

6) δ 10.64 (s, 1H), 10.17 (br s, 2H), 8.30 (d,

J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.84 (dd,

J = 8.3, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.25 (d,

J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 6.68 (d,

J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 6.60 (d,

J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.55 (dd,

J = 8.6, 2.4 Hz, 2H), 4.14 (s, 2H).

13C NMR (126 MHz, CD

3OD): δ

13C NMR (126 MHz, CD

3OD) δ 165.4, 161.7, 159.5, 151.9, 144.7, 131.7, 120.7, 119.6, 118.8, 116.4, 106.9, 104.1, 101.9, 94.0, 43.8, 16.8.

m/

z (HRMS) Found: 431.0981 (MH

+). C

22H

15N

4O

6 requires

m/

z = 431.0986. ν

max (ATR) 2208, 2104, 1695, 1584, 1531, 1453, 1384, 1237, 1204, 1169, 1109, 992, 909, 843, 759, 662 cm

−1. Physical and spectral data are in agreement with the literature data [

33,

34].

3.18. N-(3′,6′-Dihydroxy-3-oxo-3H-spiro[isobenzofuran-1,9′-xanthen]-6-yl)pent-4-ynamide (6a) [35]

This compound was prepared following a modified literature procedure [

35]. The reaction was carried out under argon in a flame-dried flask. A mixture of

28 (174 mg, 0.5 mmol), 4-pentynoic acid (

29) (60 mg, 0.5 mmol), and anh. DMF (4 mL) was stirred at 0 °C (ice-bath) for 5 min. Then, EDCI (115 mg, 0.6 mmol) was added and stirring was continued for 10 min at 0 °C and then at room temperature for 24 h. EtOAc (20 mL) was added, and the solution was washed with 1 M aq. NaHSO

4 (10 mL) and brine (10 mL). The organic phase was dried over anh. MgSO

4, filtered, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo. The residue was purified by CC (hexanes–EtOAc, first 2:1 toe elute non-polar impurities, then 1:3 to elute the product). Fractions containing the product were combined and evaporated in vacuo to give

6a. Yield: 52 mg (24%) of orange-brown solid.

1H NMR

1H NMR (500 MHz, MeOD) δ 7.15 (d,

J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.06 (dd,

J = 8.3, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 6.88 (d,

J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 6.69–6.59 (m, 4H), 6.53 (dd,

J = 8.7, 2.4 Hz, 2H), 2.82 and 2.66 (2 br t, 2:3, 1H), 2.62–2.57 (m, 1H), 2.51–2.47 (m, 1H), 2.46–2.41 (m, 1H), 2.36, 2.32, and 2.24 (3 t, 2:3:5,

J = 2.6 Hz, 1H). Physical and spectral data are in agreement with the literature data [

35].

3.19. 4-(11,12-Didehydro-5,6-dihydrodibenzo[b,f]azocin-5-yl)-N-(3′,6′-dihydroxy-3-oxo-3H-spiro[isobenzofuran-1,9′-xanthen]-6-yl)-4-oxobutanamide (6b)

The reaction was carried out under argon in a flame-dried flask. A mixture of DBCO-acid 17 (153 mg, 0.5 mmol) and anh. DMF was stirred at 0 °C (ice-bath) for 5 min. Then, EDCI (115 mg, 0.6 mmol) was added and stirring at 0 °C continued for 10 min. Next, 6-aminofluoresceine (28) (174 mg, 0.5 mmol) was added and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. Most of DMF was evaporated in vacuo until approximately 1 mL of DMF left. EtOAc (20 mL) was added, and the solution was washed with 1 M aq. NaHSO4 (2 × 10 mL), brine (10 mL), and sat. aq. NaHCO3 (20 mL). The aqueous NaHCO3 phase was acidified with 2 M aq. HCl until pH 1 and the precipitate was collected by filtration to give 6b. Yield: 25 mg (8%) of brown solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.35, 10.32, 8.28 and 8.23 (4 s, 1:3:1:3, 1H), 10.13 (s, 1H), 7.77–7.61 (m, 3H), 7.58–7.43 (m, 3H), 7.42–7.25 (m, 3H), 7.25–7.15 (m, 2H), 7.08–6.85 (m, 2H), 6.83–6.47 (m, 5H), 5.06 (dd, J = 14.1, 5.3 Hz, 1H), 3.65 (d, J = 14.1 Hz, 1H), 2.81–2.56 (m, 3H), 2.41–2.24 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (126 MHZ, CD3OD) δ 164.6, 163.8, 151.8, 151.4, 147.9, 147.7, 143.2, 143.1, 143.0, 139.9, 137.1, 125.1, 124.0, 123.9, 121.2, 121.1, 120.5, 120.5, 120.2, 120.2, 119.6, 119.4, 118.7, 117.0, 117.0, 114.4, 106.1, 104.3, 97.0, 94.0, 47.2, 23.3, 21.3. m/z (HRMS) Found: 635.1808 (MH+). C39H27N2O7 requires m/z = 635.1813. νmax (ATR) 2151, 2043, 1754 (C=O), 1603, 1481, 1425, 1253, 1204, 1160, 1110, 1072, 993, 848, 752 cm−1.

3.20. 3′,6′-Dihydroxy-3-oxo-N-(prop-2-yn-1-yl)-3H-spiro[isobenzofuran-1,9′-xanthene]-6-carboxamide (6c) [36,37]

This compound was prepared according to a slightly modified literature procedure for the preparation of closely related fluorescein-6-carboxamides [

54]. Et

3N (418 μL, 303 mg, 3 mmol) and DMAP (6 mg, 50 μmol) were added to a stirred solution of carboxyfluorescein

30 (188 mg, 0.53 mmol) and DSC (282 mg, 1.1 mmol) in anh. DMF (8 mL) and the mixture was stirred at room temperature in dark for 1 h. Then, propargylamine (

31) (86 μL, 69 mg, 1.25 mmol) was added and stirring in the dark at room temperature continued for 2 h. Volatile components were evaporated in vacuo, the residue was dissolved in EtOAc (20 mL), and the solution was washed with 1 M aq. NaHSO

4 (2 × 10 mL) and brine (1 × 10 mL). The organic phase was dried over anh. Na

2SO

4, filtered, the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo, and the residue was purified by CC (silica gel, CH

2Cl

2–MeOH, 8:1). Fractions containing the product were combined and evaporated in vacuo. The crude product

6c (25 mg, 12%) was dissolved in EtOAc (30 mL), the solution was transferred to a separatory funnel and shaken with sat. aq. NaHCO

3 (3 × 15 mL). The combined aqueous phase was transferred to a separatory funnel, acidified with 2 M aq. HCl to pH 1, EtOAc (50 mL) was added, and the biphasic system was shaken and left to settle. The precipitate, which was formed between the organic and the aqueous phase, was collected by filtration to give

6c. Yield: 12 mg (6%) of red solid.

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d

6) δ 10.27 (br s, 2H), 9.35 (br t,

J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 8.47 (s, 1H), 8.26 (br d,

J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (br d,

J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.72 (br s, 2H), 6.56 (br q,

J = 8.7 Hz, 4H), 4.11 (br t,

J = 3.8 Hz, 2H), 3.16 and 2.89 (2 br s, 1:1, 1H).

13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d

6) δ 169.0, 165.8, 159.9, 155.2, 152.3, 135.9, 135.2, 129.6, 126.9, 124.8, 124.1, 113.3, 109.4, 102.8, 90.4, 81.1, 73.3, 29.3.

m/

z (HRMS) Found: 414.0969 (MH

+). C

24H

16NO

6 requires

m/

z = 414.0972. Spectral data are in agreement with the literature data [

36,

37].

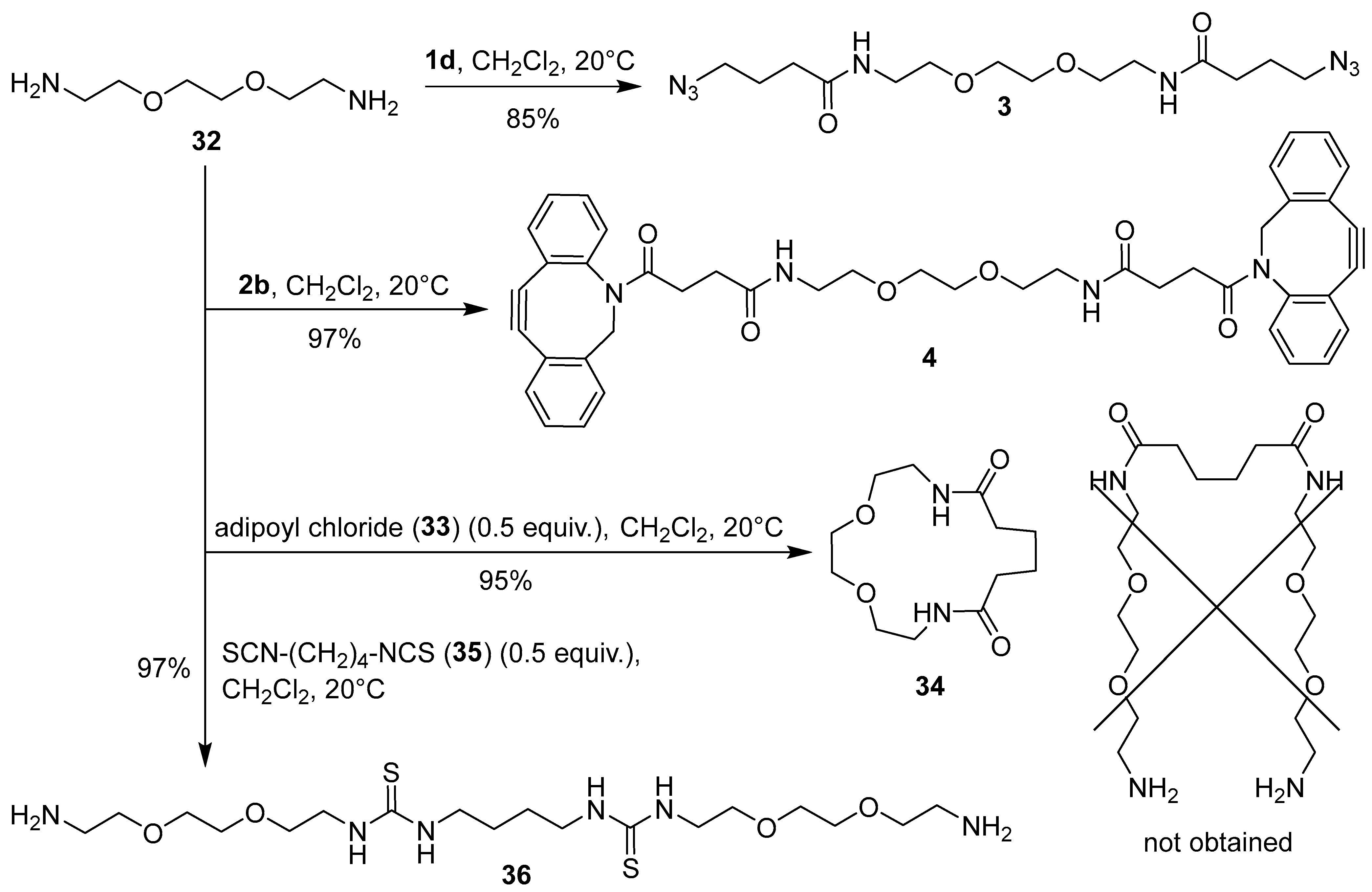

3.21. N,N′-{[Ethane-1,2-diylbis(oxy)]bis(ethane-2,1-diyl)}bis(4-azidobutanamide) (3)

Et3N (333 μL, 242 mg, 2.4 mmol) was added to a stirred solution of 2,2′-[ethane-1,2-diylbis(oxy)]bis(ethan-1-amine) (32) (147 μL, 148 mg, 1 mmol) and N-(4-azidobutanoyl)benzotriazole (1d) (470 mg, 2 mmol) in MeCN (10 mL) and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. Volatile components were evaporated in vacuo and the residue was purified by CC. First benzotriazole was eluted with EtOAc–hexanes 1:1, followed by elution of the product with MeOH. Fractions containing the product were combined and evaporated in vacuo to give 3. Yield: 316 mg (85%) of a yellowish solid, m.p. 40–55 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.12 (br s, 1H), 3.60 (br s, 2H), 3.55 (br t, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H), 3.45 (br q, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H), 3.35 (br t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.28 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.92 (p, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 171.9, 70.3, 69.9, 50.9, 39.3, 33.2, 24.9. m/z (HRMS) Found: 371.2153 (MH+). C14H27N8O4 requires m/z = 371.2150. νmax (ATR) 3252, 2866, 2094, 1625 (C=O), 1564, 1457, 1422, 1341, 1253, 1122, 1031, 893, 853, 743 cm−1.

3.22. N,N′-{[Ethane-1,2-diylbis(oxy)]bis(ethane-2,1-diyl)}bis[4-oxo-4-(11,12-didehydro-5,6-dihydrodibenzo[b,f]azocin-5-yl)butanamide] (4)

Et3N (384 μL, 278 mg, 2.76 mmol) was added to a stirred solution of 2,2′-[ethane-1,2-diylbis(oxy)]bis(ethan-1-amine) (32) (169 μL, 170 mg, 1.15 mmol) and N-[4-oxo-4-(5-aza-3,4:7,8-dibenzocyclooctyn-5-yl)butananoyl]benzotriazole (2b) (934 mg, 2.3 mmol) in DMF (10 mL) and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. Volatile components were evaporated in vacuo and the residue was purified by CC. First benzotriazole was eluted with EtOAc–EtOH 10:1, followed by elution of the product with MeOH. Fractions containing the product were combined and evaporated in vacuo to give 4. Yield: 805 mg (97%) of yellow-brown resin. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.70–7.56 (m, 2H), 7.51–7.46 (m, 2H), 7.39–7.32 (m, 6H), 7.30–7.15 (m, 6H), 6.36 and 6.31 (2t, 1:1, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 5.11 and 5.08 (2s, 1:1, 2H), 3.61 (dd, J = 13.8, 2.6 Hz, 2H), 3.57–3.48 (m, 4H), 3.47–3.36 (m, 4H), 3.35–3.23 (m, 4H), 2.81–2.70 (m, 2H), 2.41–2.31 (m, 2H), 2.12 and 2.03 (2dt, 1:1, J = 15.1, 6.1 Hz, 2H), 1.91 and 1.84 (2dt, 1:1, J = 16.8, 6.0 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.4, 172.4, 172.3, 172.3, 162.7, 151.5, 148.2, 148.2, 132.3, 132.3, 129.5, 129.5, 128.8, 128.7, 128.2, 128.2, 128.2, 127.8, 127.8, 127.1, 127.1, 125.6, 125.5, 123.3, 123.2, 122.6, 114.8, 114.8, 108.0, 70.3, 69.9, 69.8, 55.6, 50.8, 39.3, 39.3, 36.6, 31.5, 31.3, 31.1, 30.3, 30.2. Multiple signals for carbon nuclei are due to the presence of isomers (rotamers). m/z (HRMS) Found: 723.3162 (MH+). C44H43N4O6 requires m/z = 723.3177.

3.23. Synthesis of 1,4-Dioxa-7,14-diazacyclohexadecane-8,13-dione (34) [56,57]

The reaction was carried out under argon using a flame-dried flask and a rubber septum. Adipoyl chloride (

33) (145 μL, 181 mg, 1 mmol) was dissolved in anh. CH

2Cl

2 (10 mL) and the stirred solution was cooled to 0 °C (ice-bath). Diamine

32 (292 μL, 296 mg, 2 mmol) was then added slowly via syringe at 0 °C. Ice-bath was removed and the obtained suspension was stirred at room temperature for 16 h. The precipitate was collected by filtration and dried in vacuo over NaOH pellets at room temperature for 24 h to give

34. Yield: 245 mg (95%) of a yellowish solid, m.p. 111–131 °C, lit. Reference [

56] m.p. 153–155 °C.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl

3) δ 6.07 (br s, 2H), 3.62 (br s, 4H), 3.59–3.54 (m, 4H), 3.49–3.43 (m, 4H), 2.27–2.22 (m, 4H), 1.72–1.65 (m, 4H).

m/

z (HRMS) Found: 259.1652 (MH

+). C

12H

23N

2O

4 requires

m/

z = 259.1650. ν

max (ATR) 3291, 2868, 1635, 1552, 1460, 1350, 1296, 1177, 1139, 1097, 1033, 982, 937, 864, 823, 696 cm

−1. Spectral data are in agreement with the literature data [

56,

57].

3.24. Synthesis of 1,1′-(Butane-1,4-diyl)bis(3-{2-[2-(2-aminoethoxy)ethoxy]ethyl}thiourea) (36)

Diamine 32 (292 μL, 296 mg, 2 mmol) was added to a solution of 1,4-diisothiocyanatobutane (35) (172 mg, 1 mmol) in Et2O (2 mL), the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 16 h, and volatile components were evaporated in vacuo to give 36. Yield: 456 mg (97%) of a yellow resin. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.68 and 7.09 (2s, 1:2, 2H), 3.89–3.36 (m, 24H), 3.01–2.90 (m, 2H), 2.87 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H), 2.47 br (s, 6H), 1.72–1.58 (br m, 4H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 183.6, 72.6, 70.3, 70.2, 70.1, 70.0, 68.1, 44.8, 44.2, 41.5, 40.6, 31.0, 26.4, 26.2, 25.7. Multiple signals for carbon nuclei are due to the presence of isomers (rotamers). m/z (HRMS) Found: 468.2555 (M+). C18H40N6O4S2 requires m/z = 468.2552. νmax (ATR) 3260, 3067, 2863, 1544, 1344, 1283, 1096, 698 cm−1.

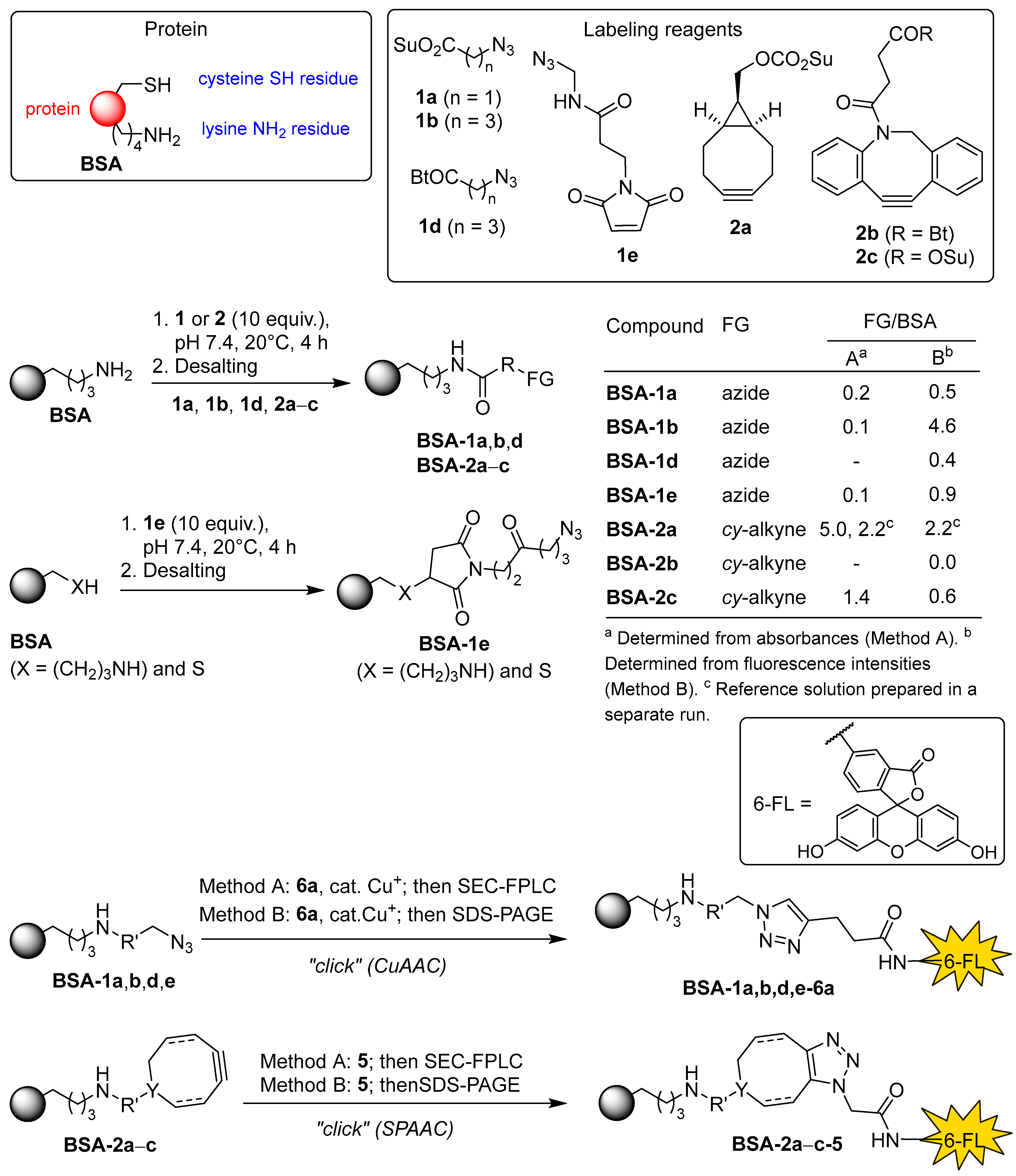

3.25. Preparation of Stock Solutions of Azide- and Cyclooctyne-Functionalized Proteins BSA-1 and BSA-2 and Determination of Molar Loading (FG/BSA) from Molar Absorbances (Method A)

First, stock solutions of

BSA-1a,

BSA-1b,

BSA-1e,

BSA-2a, and

BSA-2c were prepared. Five 1.5 mL PP vials were charged with reagents

1a,

1b,

1e,

2a, and

2c (1 mg, 5.0, 4.4, 4.0, 3.4, and 2.5 μmol, 10 equiv.) and a solution of

BSA (33.2, 29.2, 26.4, 22.6, and 16.6 mg, 0.50, 0.44, 0.40, 0.34, and 0.25 μmol, 1 equiv.) in PBS buffer (1 mL) was added to each PP vial. The mixtures were stirred (400 min.

−1) at 20 °C for 24 h. Reagent

1e dissolved completely, while reagents

1a,

1b,

2a, and

2c remained partially undissolved. The obtained stock solutions of

BSA-1a,

BSA-1b,

BSA-1e,

BSA-2a, and

BSA-2c were stored at 4 °C. Next, aliquots (130 μL) of the crude

BSA-1 and

BSA-2 solutions were taken and excess small molecular reagents and byproducts were removed by desalting. To purified cyclooctyne-conjugates

BSA-2a (44.2 nmol) and

BSA-2c (32.5 nmol) excess fluorescent probe

5 was added (1.5 mM, 295 and 220 μL, 443 and 330 nmol, respectively, 10 equiv.). To the purified azide-conjugates

BSA-1a (65 nmol),

BSA-1b (57.2 nmol), and

BSA-1e (52 nmol) excess alkyne-fluorescent probe

6a (1.5 mM, 433, 370, and 345 μL, 650, 572, and 520 nm, respectively, 10 equiv.) and 1.25 μL of an aqueous solution of CuSO

4 (10 mM, 12.5 nmol) and ascorbic acid (50 mM, 62.5 nmol) were added. The reaction mixtures were stirred (400 min

−1) at 20 °C for 3 days, aliquots (350 μL) were taken and purified by SEC-FPLC. A Superdex 200 10/300 GL size exclusion column (formerly GE Healthcare Life Sciences, now Cytiva), equilibrated in PBS buffer (pH 7.4) and a flow rate of 0.5 mL·min

−1, was used to purify the samples. Fractions containing the highest concentration of protein were collected to afford the fluorescently labeled proteins

BSA-1a-6a,

BSA-1b-6a,

BSA-1e-6a,

BSA-2a-5, and

BSA-2c-5. Next, molar loading FG/BSA was determined for each labeled protein on the basis of absorbances measured at 280 nm and 498 nm (for FG/BSA values see

Scheme 5, Method A). In a separate run, a solution of

BSA-2a-6a with FG/BSA = 2.2 was prepared again to be used as a standard reference solution for rapid determination of FG/BSA from fluorescence intensities (see Method B, see

Section 3.26).

3.26. Procedure for Rapid Determination of Molar Loading (FG/BSA) of Functionalized Proteins BSA-1 and BSA-2 from Fluorescence Intensities (Method B)

Stock solutions of the crude functionalized proteins

BSA-1a,

b,

d,

e and

BSA-2b,

c were prepared as described previously (see

Section 3.25) by treatment of

BSA with 10-fold excess reagents

1 and

2. Also this time, only reagent

1e dissolved completely, while reagents

1a,

1b,

2a,

2b, and

2c remained partially undissolved. Aliquots (100 μL) of the crude

BSA-1 and

BSA-2 solutions were taken, excess small molecular reagents and byproducts were removed by desalting, and the purified

BSA-1 and

BSA-2 solutions were diluted with water to

c ~ 2 mg mL

−1 (~30 μM),and aliquoted (6 × 5 μL, 6 × ~0.15 nmol). To each aliquot PBS buffer containing 1% SDS (39 μL) was added, the mixture was heated at 90 °C for 10 min and cooled to room temperature. To each aliquot of cyclooctyne-conjugates

BSA-2b,c large excess of azide-fluorescent probe

5 (2.5 μL, 50 mM, 125 nmol) was added. To each aliquot of azide-conjugates

BSA-1a,b,d,e large excess of alkyne-probe

6a (2.5 μL, 50 mM, 125 nmol) and 3.5 μL of an aqueous solution of CuSO

4 (50 mM, 165 nmol), TCEP (100 mM, 330 nmol), and TBTA (3.4 mM, 11.9 nmol) was added. The reaction mixtures were stirred (400 min

−1) in the dark for 1 h, followed by the addition of 4V (200 μL) of cold (0 °C) acetone and centrifugation (13,000×

g, 4 °C, 2 min). The supernatants were decanted, and the proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. To each fluorescently labeled protein 5 μL 4× SDS sample buffer, supplemented with 10%

v/

v β-mercaptoethanol (4× SDS+R), was added, the mixtures were stirred (400 min

−1) at 37 °C for 30 min. Labeled proteins

BSA-1-5 and

BSA-2-6 and the reference standard solution

BSA-2a-6a with known molar loading (FG/BSA = 2.2, see

Section 3.25) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Afterwards, gels were briefly washed with deionized H

2O and scanned with a ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad) using settings for ProQ Emerald 300 detection. The same gels were subsequently stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue, destained, and photographed using the same imager. The molar loading FG/BSA was then determined by analyzing the digital image data obtained (Emerald 300 and Coomasie Brilliant Blue) using Image Lab Software (Bio-Rad).

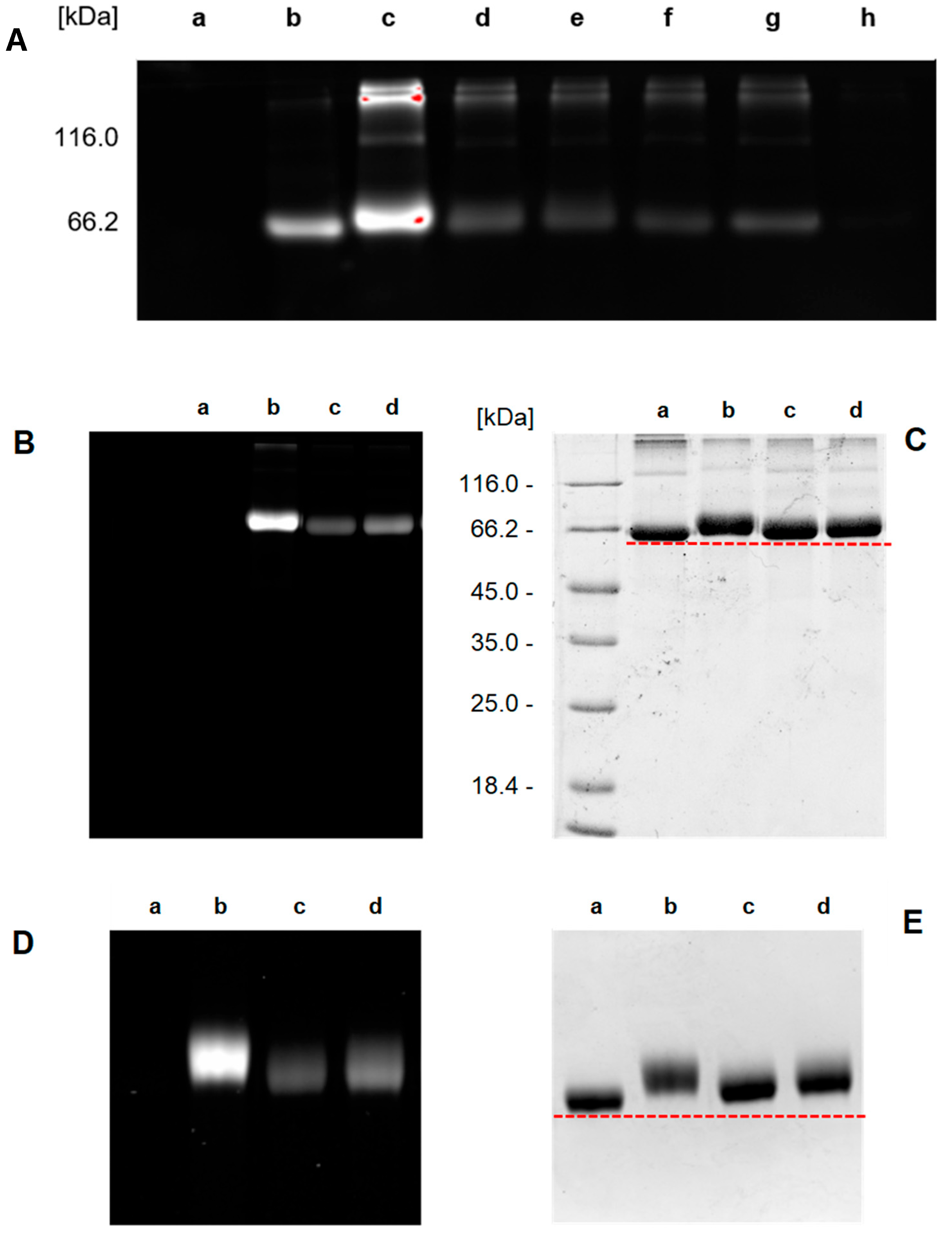

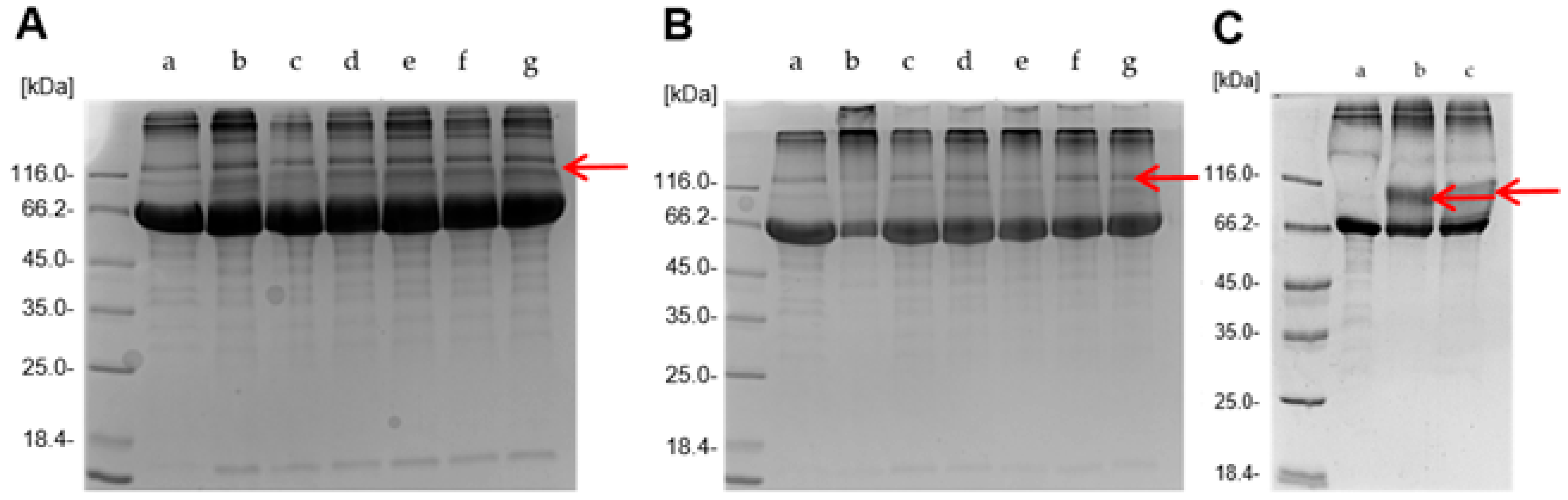

3.27. Procedure for Direct Covalent Cross-Linking of Functionalized Proteins BSA-1 and BSA-2 (Method C)

Solutions of the purified functionalized proteins

BSA-1a,

BSA-1b,

BSA-1e,

BSA-2a, and

BSA-2c were prepared as described above (see

Section 3.25) and their FG/BSA (0.2, 0.1, 0.1, 5.0, and 1.4, respectively) was determined by Method A (see

Section 3.25 and

Scheme 5). Twelve 1.5 mL PP vials were charged with purified cyclooctyne-conjugates

BSA-2a and

BSA-2c (6 × 100 μL each) and mixed with azide-conjugates

BSA-1a,

BSA-1b, and

BSA-1e (2 × 100 μL each and 2 × 500 μL each). The mixtures were stirred at 20 °C for 4 h and then analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Afterwards, gels were briefly washed with deionized H

2O, stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue, destained and photographed with a ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad).

3.28. Procedure for Covalent Cross-Linking of Functionalized Proteins BSA-1b and BSA-2a Using Bifunctional Linkers 3 and 4 (Method D)

Solutions of the purified functionalized proteins

BSA-1b and

BSA-2a were prepared (see

Section 3.25) and their FG/BSA (4.6 and 2.2, respectively) was determined by Method B (see

Section 3.26 and

Scheme 5). A 1.5 mL PP vial was charged with the purified azide-conjugate

BSA-1b (200 μL, 439 μM, 87.8 nmol; FG/BSA = 4.6, n

(azide) = 404 nmol, 1 equiv.) and a solution of bis-cyclooctyne

4 in DMSO (72.9 μL, 2.77 mM in DMSO, 202 nmol, 0.5 equiv.). In the same manner, cyclooctyne conjugate

BSA-2a (200 μL, 341 μM, 68.3 nmol; FG/BSA = 2.2, n

(cyclooctyne) = 150.3 nmol, 1 equiv.) was mixed with bis-azide

3 in PBS buffer (13.9 μL, 5.4 mM, 75.1 nmol, 0.5 equiv.). Both reaction mixtures were shaken at room temperature for 24 h and SDS-PAGE analysis was performed. Afterwards, gels were briefly washed with deionized H

2O, stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue, destained, and photographed with a ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad).